Causes of Geographical Diversity

Absolute diversity (cf. p. [263]) poses a purely speculative problem. Diversity of relationship, on the other hand, is amenable to observation and can be reduced to unity. French and Provençal, for example, both go back to Vulgar Latin, which evolved differently in northern and southern Gaul, and there is concrete evidence for their common origin.

In order to understand what happens, let us imagine theoretical conditions as simple as possible, which will allow us to identify the essential cause of territorial differentiation. Let us ask what would happen if a language spoken at one clearly delimited place – a small island, for example – was taken by colonists to some other place, also clearly delimited – say another island. After a certain time, it will be possible to detect various differences of vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, etc. between the language of the first location (1) and the language of the second location (2).

It must not be supposed that the language taken to 2 will change while the language of 1 remains stationary, or the reverse. Innovation may occur in either or in both. Given a linguistic feature a which may be replaced (by b, c, d, etc.), the differentiation can occur in three different ways:

[271]

A study of differentiation thus cannot be unilateral: innovations in both languages are of equal importance.

What brings about these differences? If anyone believes it is just the distance between 1 and 2, he is the victim of an illusion. Distance alone can have no effect upon a language. The day after their arrival at 2, the colonists from 1 spoke exactly the same language as the day before. One forgets the time factor, because it is less concrete than distance: but in fact it is time on which linguistic differentiation depends. Geographical diversity has to be translated into temporal diversity.

Take two contrasting features b and c, and let us suppose that b has never been known to change to c, nor vice versa. In order to trace how unity has given way to diversity, it is necessary to go back to the original feature a which b and c later replaced. Hence the following schema of geographical differentiation will be valid for all such cases.

The separation of the two languages at 1 and 2 is the tangible form taken by the phenomenon, but not its explanation. Doubtless the differentiation would not have occurred had it not been for the distance, however small, between 1 and 2. But distance itself does not give rise to differences. Just as one cannot estimate volume on the basis of a single surface, but only by recourse to a third dimension – depth – so the schema of geographical differentiation is not complete unless it is projected in time.

[272]

It may be objected that varying circumstances, climate, topography, ways of life (as between, for instance, mountain dwellers and sea folk) may affect the language, and that in these cases the variations will be geographically conditioned. But these influences are debatable (cf. p. [203]) and even if they were proven there is one further distinction to be drawn. The direction of change is attributable to circumstances: it is determined by imponderable factors acting in each particular case, and one can neither prove nor describe their influence. For instance, a u becomes ü at a given time, in given circumstances. But why did it change at that particular time and place, and why did it change to ü and not to o? It is impossible to say. But the change itself, apart from its specific direction and particular manifestations, – in short, the instability of the language – depends on time alone. Geographical diversity is thus a secondary aspect of the general phenomenon. The unity of related languages is to be traced only through time. Unless the student of comparative linguistics fully realises this, all kinds of misconceptions lie in wait for him.

§2 Linguistic areas affected by time

Let us now take the case of a monoglot country: that is to say, where the same language is uniformly spoken by a stable population. Gaul in 450 A.D., with Latin firmly established everywhere, would be an example. What is going to happen?

[273]

(1) Since language is never absolutely stationary (cf. p. [110] ff.), after a certain time has elapsed, the language will no longer be the same.

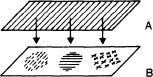

(2) Evolution will not be uniform over the whole territory, but will vary from place to place. A language has never been found to change in the same way throughout the whole area where it is spoken. So the realistic model is not

but rather

How does the differentiation which will eventually produce dialect forms of all kinds begin and develop? This is more difficult than it might at first sight appear. The phenomenon exhibits two principal features.

(1) Evolution takes the form of successive, specific innovations. These are partial facts that can be enumerated, described and classified by type (phonetic, lexicological, morphological, syntactic, etc.).

[274]

(2) Each innovation has its own particular area. Either this area covers the whole territory and so creates no dialect division (which is rare), or else it covers only part of the territory and thus becomes a dialect feature of that part (which is usually the case). Phonetic change will serve as an example, although what follows may be applied to any innovation. Suppose the change from a to e divides the territory in one way, and the change from s to z divides the same territory in another way.

The existence of these different areas explains the differences which are found at all points in the territory over which a language is spoken, assuming the language follows its own natural course of evolution. These areas cannot be predicted. Their extent cannot be determined in advance. All that can be done is to describe them when they are established. Superimposed on a map, they cut across one another and overlap in patterns of great complexity. Sometimes they show surprising configurations. For example, Latin c and g before a became tš and dž respectively, then š and ž (e.g. cantum → chant ‘song’, virga → verge ‘rod’), over the whole of northern France except Picardy and part of Normandy, where c and g remained unchanged: cf. Picard cat for chat ‘cat’, rescapé for réchappé ‘survivor’ (which has recently passed into French), and vergue ‘rod’ from Latin virga.

What is bound to be the result when all this is added together? Whereas a single language was formerly in use throughout a given area, after five or ten centuries have elapsed people living at opposite points on the periphery of the area will in all probability no longer understand one another. On the other hand, those living at any given place will still understand the speech of neighbouring regions. A traveller crossing the country from one side to the other will find only slight differences between one locality and the next. But as he proceeds the differences accumulate, so that in the end he finds a language which would be incomprehensible to the inhabitants of the region he set out from. Or starting from the centre and proceeding to the periphery, he will find the divergences progressively increase whichever direction he takes, although in different ways depending on the direction chosen.

[275]

The special features noted in the speech of one village will recur in the localities round about, but it will be impossible to predict how far each of them extends. At Douvaine, a town in the Haute-Savoie, the name of the city of Geneva is pronounced đenva. This pronunciation is found very far afield to the east and south. But on the other side of Lake Léman the pronunciation is dzenva. It is not a question of two clearly distinct dialects: for another feature the boundaries would be different. At Douvaine the word for ‘two’ in daue, but this pronunciation extends over a much smaller area than đenva: a few kilometres away, at the foot of the Salève, ‘two’ is due.

§3 Dialects have no natural boundaries

The usual conception of dialects nowadays is quite different. They are envisaged as clearly defined linguistic types, determinate in all respects, and occupying areas on a map which are contiguous and distinct (a, b, c, d, etc.).

[276]

But natural dialect changes give a quite different result. As soon as linguistics began to study each individual feature and establish its geographical distribution, the old notion of a dialect had to be replaced by a new one, which can be defined as follows: there are no natural dialects, but only natural dialect features. Or – which comes to the same thing – there are as many dialects as there are places.

The notion of natural dialects is thus in principle incompatible with the notion of a region. The linguist is faced with a choice. One possibility is to define a dialect by the totality of its features. In this case, one must concentrate on a single locality at a given point on the map. As soon as one moves from this locality, one will no longer be dealing with exactly the same set of dialect features. The other possibility is to define a dialect on the basis of just one feature. In this case, naturally, there will be an area, corresponding to the geographical extension of the feature selected. But it is hardly necessary to point out that this latter procedure is an artificial one, and the boundaries thus established correspond to no dialectal reality.

Research into dialect features was the point of departure for linguistic cartography, of which the model is Gilliéron’s Atlas linguistique de la France. For Germany, one should mention also Wenker’s atlas.1 The form of such an atlas is determined in advance, for it is necessary to study the country region by region, and for each region one map can record only a few dialect features. Any region will require a large number of maps to show the various phonetic, lexicological, morphological, etc. features superimposed within it. Research of this nature requires careful organisation, with systematic inquiries on the basis of questionnaires, the assistance of local helpers, and so on. In this connexion one may point to the survey of the Romance dialects of Switzerland as an example. One advantage of linguistic atlases is that they provide materials for dialectology: numerous studies recently have been based upon Gilliéron’s atlas.

[277]

The term ‘isogloss lines’ or ‘isoglosses’ has been introduced to designate the boundaries of dialect features. The expression is modelled upon isotherm. But it is unclear and inappropriate, for it means ‘having the same language’. Granted that glosseme means ‘linguistic feature’, it would be more accurate to call them isoglossematic lines, if this term were usable. We would prefer to call them waves of innovation, taking up the image originally suggestion by J. Schmidt, which the following chapter will give reasons for adopting.

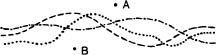

When one looks at a linguistic map, one sometimes sees two or three of these waves almost coinciding or even merging over a certain distance.

It is evident that two points A and B separated by a zone of this kind will show a certain accumulation of contrasts and constitute two fairly distinct forms of speech. It may also happen that these convergences are not merely partial, but mark out the entire perimeter of two or more areas.

[278]

When these convergences are numerous, one can use ‘dialects’ as a roughly appropriate term. The convergences are explained by social, political, religious, etc. factors, which we are completely ignoring for present purposes. These convergences disguise but never entirely obscure the primary and natural phenomenon of differentiation into independent areas.

§4 Languages have no natural boundaries

It is difficult to say what the difference is between a language and a dialect. Often a dialect is called a language because it has a literature: that is true of Portuguese and Dutch. The question of intelligibility also plays a part. People who cannot understand one another are generally described as speaking different languages. However that may be, languages which have developed in one continuous area with a settled population exhibit the same phenomena as dialects, but on a larger scale. They show waves of innovation over a territory where a number of different languages are spoken.

In the ideal conditions postulated, it is no more feasible to determine boundaries separating related languages than to determine dialect boundaries. The extent of the area involved makes no difference. Just as one cannot say where High German ends and Low German begins, so also it is impossible to establish a line of demarcation between German and Dutch, or between French and Italian. Taking points far enough apart, it is possible to say with certainty ‘French is spoken here; Italian is spoken there’. But in the intervening regions, the distinction becomes blurred. The notion of smaller, compact intermediate zones acting as linguistic areas of transition (for example, Provençal as a half-way house between French and Italian) is not realistic either. In any case, it is impossible to imagine in any shape or form a precise linguistic boundary dividing an area covered throughout by evenly differentiated dialects. Language boundaries, just like dialect boundaries, get lost in these transitions. Just as dialects are only arbitrary subdivisions of the entire surface covered by a language, so the boundaries held to separate two languages can only be conventional ones.

[279]

None the less, abrupt geographical transitions from one language to another are very common. How do they arise? They are the outcome of circumstances which have militated against the survival of gradual, imperceptible transitions. Population movement is the most important factor. Throughout history, peoples have migrated. Over the course of centuries, these migrations have complicated the picture and in many instances obliterated the vestiges of linguistic patterns of transition. The Indo-European family is a typical example. Originally these languages must have been very closely connected, forming an uninterrupted chain of linguistic areas. The main ones we can reconstruct in broad outline. In terms of linguistic features, Slavic overlaps with Iranian and Germanic, and this corresponds to the geographical distribution of the languages in question. Similarly, Germanic may be considered as forming a link between Slavic and Celtic, which in turn is closely related to Italic. Italic is intermediate between Celtic and Greek. Not knowing the geographical location of any of these languages, a linguist could assign relative geographical positions to them without any trouble. And yet as soon as we consider a boundary between two linguistic groups, such as Slavic and Germanic, we find a clear gap with no transition. The languages do not merge into one another, but stand opposed. This is because the intermediate dialects have disappeared. Neither the Slavs nor the Germans remained settled. They migrated and conquered land from one another. The Slav and Germanic populations who are neighbours today are no longer those formerly in contact. Imagine that Italians from Calabria were to come and settle on the borders of France. This migration would automatically wipe out the imperceptible transition which, as we have noted, links Italian with French. Facts of this kind account for the situation in the Indo-European family.

[280]

But other causes also contribute to obliterate transitions; for example, the extension of a common language at the expense of local dialects (cf. p. [267] ff.). Today literary French (the former language of the Ile-de-France) meets official Italian (the generalised dialect of Tuscany) at the frontier. It is only by chance that we can still find transitional dialects in the western Alps. Along many other linguistic borders all trace of intermediate forms of speech has been lost.

Notes

1 Cf. also Weigand’s Linguistischer Atlas des dakorumänischen Gebiets (1909), and Millardet’s Petit atlas linguistique d’une région des Landes (1910).