Chapter 11

Entrepreneurship in France

FOR DECADES, THERE HAVE BEEN two schools of thought about the business development of France in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: the pessimists' and the optimists'. The pessimists emphasize that British GNP grew faster than the French during the nineteenth century and exceeded the French by 50 percent at the beginning of the twentieth century. The optimists focus attention on the performance of French small-scale output in the secondary sector and assert that although the French path to economic modernity was different, it was no less efficient. Perhaps both are right: French national data hide large regional variations. In some places the Industrial Revolution was fast and was led by dynamic employers, whereas in others it was slow and incomplete. The behavior of local employers constituted, independently of the cost of raw materials or of the availability of labor, a comparative advantage for the industrial development of some French regions. On the national level, the state made efforts to stimulate industrialization, beginning in the epoch of Louis XIV and his finance minister, Colbert. But a tradition of free enterprise also existed in France in each period and flourishes now, in a time of international competition.

The First Rise of French Industry (1815–1870)

The Industrial Revolution began in France after that of the United Kingdom. It was delayed by the disorders of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. But the Revolution abolished all guild restrictions, and the Code of Commerce, promulgated in 1807 under Napoleon, created favorable conditions to entrepreneurship. State institutions, such as engineering schools, the Académie des Sciences, and the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, helped the dissemination of technological innovations. In 1815, with the return of peace, the process of industrialization accelerated and, at the time of the conclusion of the Anglo-French free trade treaty of 1860, French industrial output amounted to 40 percent of that of Britain. In 1865, the engine builder Eugene Schneider could proudly announce to the French Parliament that he had succeeded in selling fifteen locomotives to England and said that it was the “greatest joy” of his life. At that time, at the end of the 1860s, French industrial output was also exceeded by those of Germany and the United States, but remained fourth in the world until about 1930.

The Scarcity of Large Companies

French industrialization took place in a context of costly coal and high protectionism. Coal was rare, except for the small basins of the Massif Central and the north. A law voted in 1816 protected by prohibitions or very high customs duties the textile and iron industries. The persecutions of Protestants by Louis XIV (Lüthy 1955–61) and then the troubles under the Revolution (Perrot 1982; Bonin 1985; Crouzet 1989; Aerts and Crouzet 1990) had more or less durably weakened entrepreneurship in many parts of France.

The old techniques (cast iron made with charcoal, manual weaving, hydraulic mills), less greedy in energy and capital, coexisted until about 1860 with the most modern modes of production. Big factories, like the glass producer Saint-Gobain, were rare. Only the mines, the waterways, the large iron and steel firms, and the railroads were financed by limited-liability companies, whose creation was subject to authorization until 1867. The capital of industrial firms was generally provided by the founder's family, later by self-financing (Lévy-Leboyer 1974, 1985; Marseille 2000). The passage from the small workshop consuming little energy and still using largely craft-based techniques toward the large company using the steam engine and the latest techniques occurred slowly and at very unequal rates that varied among areas. French producers made an effort to compensate for their weakness in mechanization by the aesthetic quality of their product. They specialized in printed cottons, silk textiles, and luxury handicraft products (articles de Paris). Engineering colleges gave artistic drawing an important place in their curriculum.

The geographical distribution of the dynamic centers is instructive. During the nineteenth century, the southwest of France was industrially inactive and remained anchored in an agricultural and craft-based economy (Armengaud 1960; Crouzet 1959; Poussou 2000). The Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts (in particular the ports of Nantes and Bordeaux, on the Atlantic Ocean) suffered much from the British maritime blockade. But after the war, from 1815, their tendency to deindustrialization did not stop (Poussou 1989; Butel 1991; Armengaud 1960). Industrial employers put their money in land and real estate with poor but less dubious profits. In contrast, factory development was remarkably dynamic in Paris, at Lyons, and, from the beginning of the nineteenth century, in the peripheral zones of northern and eastern France. Machine cotton spinning developed quickly in the north (Lille, Roubaix, Tourcoing) and in Alsace (Toulemonde 1966; Barbier 1989; Pouchain 1998; Daumas 2004b; Hau 1987; Stoskopf 1994; Hau and Stoskopf 2005). After the end of Napoleonic Wars, Nicolas Koechlin and Daniel Dollfus-Mieg, whose factories employed thousands, exported printed fabrics from Mulhouse to all the world. Nicolas Schlumberger introduced in 1817 in Guebwiller the British technique for fine yarn and the production of mule jennies. In 1826 Marc Seguin built the railway line Lyons-Saint-Etienne and, three years later, launched the production of a new type of locomotive, with tubular boilers, in Lyons.

Barriers to Diffusion of Entrepreneurship in France at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century

At the beginning of nineteenth century, several factors exerted a negative influence on the development of the entrepreneurship: the political power of the landowners, the attraction of gentry status or of high public office for the elites, the conflict between the Catholic Church and the Revolution, and finally, increasingly radical protests coming from the intellectual and artistic elites.

THE POLITICAL WEIGHT OF THE LANDOWNERS

The Revolution released the peasants from seigneurial charges, but it did not call into question the urban middle-class ownership of arable land. Around Paris and the cities of southern France, many middle-class men placed their fortune in the ground. Indicator of social rank, symbol of safety, landownership remained, at least into the last quarter of the nineteenth century, a major competitor to industrial investment. The majority of the members of Parliament and senior officials were landowners, more aware of and sensitive to agricultural problems than the prospects opened by industrialization. The debates in Parliament revealed blockages about railroad construction: long-term concessions and loan guarantees were refused by the deputies. Liberalization of the creation of limited companies had to wait until 1867. The administrative and political elites were anxious about the risks of speculation or financial domination by big business. Thus, the political community was reticent about the development of large-scale industry and the growth of vast worker concentrations. The British example was, for many of them, something to be avoided, rather than a model to be followed. But after 1852, the regime of Napoleon III made bolder moves and pushed reluctant political circles toward modernization (Landes 1967; Gille 1959, 1968).

THE PRESTIGE OF THE GENTRY AND OF THE HIGH CIVIL SERVICE

A part of the entrepreneurial elite conceived enterprise as a way to gain a fortune, to buy land, and to enter into the gentry. The most famous example is that of Auguste-Thomas Pouyer-Quertier. He developed a large cotton-spinning factory in Normandy. In 1857 he was elected deputy to the French Parliament and, in 1871, became minister of finance. From this time, he neglected his firm, which declined, and he married his two daughters to noblemen. This behavior was widespread in Normandy, where industrial dynasties rarely lasted more than two generations (Barjot 1991).

There was also in bourgeois families a strong pull to the civil service. The French monarchy developed a centralized, general-purpose, and hierarchical administration. The senior civil servants were recruited after the Revolution by selective contest, and this system put into competition the best graduates of the secondary schools. The bourgeois families of Paris and the provinces made it a point of honor to enter high public office, which before the Revolution had conferred ennoblement. This attraction of talent for the service of the state diverted part of the elite from the world of enterprise. The schools of engineers created by the Monarchy at the end of the eighteenth century and later by the Republic had initially the function of providing the administration and the army with scientific and technical competences. Thereafter, things began to change; with the growth of the number of engineers in business companies, the various schools of engineering, in particular the Ecole Polytechnique, provided more and more for the needs of industry.

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND MODERNITY

France was primarily a country of Roman Catholic religion. However, the rationalist movement and then the Revolution revealed the difficulty of the Catholic Church in adapting to modernity. Among many Catholics, there occurred, starting at the end of the eighteenth century, a brutal rupture with the religious tradition: they had to choose between their traditional faith and the ideals of the Enlightenment. Part of the Catholic middle class felt obliged to give up its ancestral faith and to break with a number of traditional attitudes in order to open its mind to science and industry (Groethuysen 1927, xi, xii). In contrast, Protestants and Jews preserved their religious spirit intact throughout the nineteenth century. For the Protestant or the Jew, to make a company thrive seemed a moral duty, whereas for the agnostic, it was only a right related to ownership. The difference here was less between Catholicism and Jewish or Protestant religion than between unbelief and faith.

THE PROTESTS EMANATING FROM THE INTELLECTUAL AND ARTISTIC ELITES

After the Revolution had abolished the privileges of the aristocracy, the wealth and the social status of the entrepreneurs put them on the first rank in the French society. The most successful of these entrepreneurs could soon accumulate wealth surpassing those of the biggest landowners. After 1830, bankers and industrialists such as Jacques Laffitte or Casimir Périer under Louis-Philippe or Jean Dollfus under Napoleon III played an important role in the government. But, in removing the aristocracy, the French Revolution had invented two new rival elites: on the one hand, that of artists and intellectuals (writers, painters, musicians, etc.); on the other, that of entrepreneurs. The first despised the second, which it reproached for being deaf to passions, blind to art, and insensitive to the misery of their workforce (Heinrich 2006).

Progressively, at the end of the nineteenth century, as industrial development proceeded, the positions of some writers were radicalized; thus Emile Zola left us a particularly sinister description of large-scale industry and the coal mines. The influence of the writers on public opinion was particularly important in France. It hampered, to a degree impossible to determine, the vocation of entrepreneurs.

Local Backgrounds Favorable to Entrepreneurship

FAST INDUSTRIAL GROWTH IN THE NORTH AND EAST OF FRANCE

The north of France, Alsace, Lorraine, Franche-Comté, and the region of Lyons saw industrial output grow vigorously in the nineteenth century, along with continuity of powerful entrepreneurial dynasties. The two phenomena are correlated: because industry benefited from the presence of a middle class durably committed to the technological and commercial adventure, it was able to resist successive crises. The capacity of regional employers to pass their companies from one generation to the next was one of the hidden faces of French economic performance.

Entrepreneurship does not only lie in creating new enterprises. It lies also in developing inherited enterprise and in maintaining and using the family fortune effectively. Employers' dynasties that reached or exceeded four generations are not distributed in a random way on the map of France. One finds them only at some very special locations. Thus, the principal employers' dynasties of northern and eastern France were at the origin of companies of world notoriety. Families like Motte, Danel, Schlumberger, Dollfus-Mieg, de Dietrich, Peugeot, or de Wendel originated in a surprisingly small number of localities: Lille, Roubaix, Tourcoing in the north; Guebwiller, Mulhouse, Strasbourg in Alsace; Montbéliard in the Franche-Comté; or Lyons. The majority of these enterprises under the Second Empire belonged to families that had maintained their industrial activity over at least four successive generations (Stoskopf 1994, 32), in contrast to Normandy. The old Alsatian industrial dynasty de Dietrich had ruled its family enterprise since 1685 and is today at its tenth generation of entrepreneurs. The Koechlin family displays thirteen entrepreneurs of the sixth or seventh generation, the Schlumberger family, ten; the Dollfus family, two (Hau and Stoskopf 2005, 525–45).

In the matter of religion, one will note that entrepreneurship was especially developed in minority groups tardily integrated into French society: the Protestants and the Jews. Such families as Hottinguer, Mallet, Vernes, and Odier were Protestants from Switzerland, often of Huguenot origin. Jews of Rhenish origin, such as the families Worms and Rothschild, were among the most important in Paris. From the end of the eighteenth century, they constituted the haute banque and played an essential role in the development of railroads and large-scale industry. This “outside” contribution confirms the inhibiting aspect of official power and political centralization already observed on the geographical level.

THE TRADITION OF URBAN AUTONOMY IN THE RECENTLY INTEGRATED PROVINCES

The map of the most dynamic French industrial centers shows that the entrepreneurship was more active in the provinces of the north and the east, that is, the communities most tardily integrated into the French nation. They had not belonged before to a great centralized state and had maintained longer than elsewhere the medieval tradition of urban autonomy.

The north of France, which was attached to the Duchy of Burgundy at the end of the Middle Ages, formed part of the Rhenish area, where European technological innovation mainly developed. Industrial employers were drawn primarily from the patriciates of these cities. These territories were incorporated by Louis XIV into France: Artois in 1659 and Lille in 1668. The “capitulations” then authorized by the king made it possible for the cities of the area to preserve some autonomy. At the end of the eighteenth century, metallurgy and cotton spinning developed there in large manufactures.

The same applies to the east of France. The employer's dynasties of Alsace and Franche-Comté started as lines of municipal notables, sometimes two centuries before they created industrial companies. Strasbourg, free city of the empire, had negotiated its absorption by the Kingdom of France in 1681 by safeguarding multiple religious, institutional, and linguistic freedoms. Lorraine was attached to France only in 1766. Mulhouse, a small republic allied with the Swiss cantons, had waited until 1798 before being incorporated in the French Republic. Montbéliard, principality attached to Wurtemberg, was integrated into France only with the treaty of Lunéville, in 1801. Like all the Rhenish populations, these bourgeoisies had never benefited from the protection of a great centralized state and were accustomed to count, above all, on themselves.

FAMILY STRUCTURES INFLUENCED BY THE MODEL OF THE STEM FAMILY

As we have seen, a very clear opposition existed between the behavior of the Norman businessmen on the one hand, and those of northern and eastern France on the other. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Normandy was the leading French industrial area. But Norman employers were not much inclined to remain in industry. Their companies changed hands, and the fortunes made in industry were thereafter invested in land and buildings. The scarcity of industrial dynasties in Normandy can be related to the prevalence of looser family structures, those of the nuclear family. At their majority, children felt themselves less bound by obligations to their parents and their family heritages.

In contrast, the principal force of the employers of the north and east lay in the cohesion and extent of the family bonds. Emmanuel Todd puts the north and east of France in the “stem family” areas (1990, 62). This type of family emphasizes parental authority, which prevails even after the children reach adulthood. The consequence was the success of companies, often called “houses,” over several generations. There was clear identification between family and company. This almost always took the form of a partnership, combining a limited number of shareholders bound by the closest family ties: father and son, brothers, father and son-in-law, and so on. The transformation of these firms into limited companies occurred only after 1870, when and if funds were available; or in Alsace, to allow those of the heirs who did not want to assume German nationality to resell their share to those relatives who remained. But the shift to limited liability long remained a matter of form and masked continued family control, often for decades. These families were often large: in 30 percent of the cases, in the north, the households of entrepreneurs counted six or more children (Barbier 1989, 14). These big families wove among them multiple matrimonial bonds that made it possible to limit the wasting of fortunes and decline of training. Companies resting on less prolific families had to find external collaborators, and these could leave much to be desired, especially in matters of loyalty and remuneration.

THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGION ON ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE

In Normandy, many entrepreneurs experienced a weakening of Catholic faith toward the end of the eighteenth century. This change was often accompanied by liberation from rules of conduct now perceived as unnecessarily constraining. Only one-tenth of Norman entrepreneurs engaged in religious activities (Barjot 1991, 234). Compare the north, which remained under the influence of a rigorous Catholicism (Barbier 1989, 6; Darnton 1983, 195), and the east, faithful to Protestantism or Judaism.

Politically, the businessmen of the north were conservative, even reactionary, and few engaged in scientific studies: the influence of Catholicism worked against the Enlightenment. The major figures financed Catholic charities, and some of the children entered the clergy. The case of the banker Auguste Scalbert is typical: two of his six sons entered the clergy and three banking (Barbier 1989, 30; Hirsch 1991). What is more, the Catholicism of the north was significantly different from that of most of France. The towns of Roubaix and Tourcoing were strongly influenced in the eighteenth century by Jansenism, a belief system that stressed individual ethics and behavior more than sacramental practices (Delsalle 1987, 149–56). The same can be said about the Catholic families of silk merchants of Lyon: the family Berliet belonged to the “Petite Eglise” (Little Church), which did not accept the concordat of 1801 between the pope and Napoleon (Angleraud and Pellissier 2003, 161). The strength of these employers lay in their ethic of work and saving.

In Alsace and Franche-Comté, the largest and most durable dynasties were Protestant (Schlumberger, Koechlin, Dollfus, Peugeot) or Jewish (Dreyfus, Bloch, Blin). These minority entrepreneurs developed prosperous firms in cotton or wool spinning and mastered the printing of all kinds of textiles. They also created an industry for building machines. In Alsace, neither Protestantism nor Judaism had any problem with rationalist thought. The Reformation, because it shook the authority of tradition, encouraged more favorable attitudes to scientific advances. Hence the scientific leaning of Mulhousian bourgeois. The Koechlin and Dollfus families were descended from the famous mathematician Johann Bernouilli, and their dynasties would go on to marry with such scientific families as the Curies and the Friedels. Some of these entrepreneurs were also seen as first-rate scientists as, for example, Daniel Dollfus-Ausset and his cousin Daniel Koechlin (Mieg 1948, 32; Hau 1987, 476–80; Hau and Stoskopf 2005, 479–92). The Mulhousian manufacturers founded in 1826 the Société industrielle de Mulhouse, which promoted technological progress in Alsace by the way of conferences and publications. Science also drew in some of the Protestant metallurgists. Thus Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich was known at the end of the eighteenth century for his works on mineralogy and metallurgy.

The same can be said about the Jewish entrepreneurs. Judaism had always insisted on the obligation, for each believer, to study the holy scriptures and the Law, which meant a duty to read and remember. This led to a community attentive to and respectful of science. This parallelism of attitudes between Jews and Protestants owed much to the mutual esteem of the two communions, particularly at Mulhouse.

As one might expect, the values that Max Weber described as favorable to the growth of capitalism, namely work and thrift, were those most honored by the employers of eastern France (Weber 1905). Among Alsatian entrepreneurs, work was seen as an absolute virtue; wealth did not exempt one from the duty to work. Many Alsatian businessmen stayed at the head of their firms until death; or they retired to do research. The same for frugal living. Thus, Normandy was much more corrupted by Parisian values than Alsace (Chaline 1988, 200). Mulhousians kept the memory of the sumptuary laws that had ruled their city before its absorption into France. Frugality in turn fostered the accumulation of considerable financial resources (Hau 1987, 348–54.).

DISCIPLES OF SAINT-SIMON AND THE BELIEF IN SCIENTIFIC

AND TECHNOLOGICAL PROGRESS

On the national level, an influential group, the disciples of the comte de Saint-Simon (died 1825), promoted entrepreneurship and industrialization. The Comte had a strong faith in science. He thought that economic development would eliminate poverty and that the world of the future should be governed by scientists and engineers. The best way to do this would be to transfer wealth from the unproductive aristocracy to the productive class, the employers. His ideas were very popular among the students of French engineering schools and among Parisian bankers. His disciples, engineers like Paulin Talabot and businessmen like the brothers Emile and Isaac Pereire, tirelessly promoted his ideas in journal articles. Whereas some economists stressed the need to preserve the craft system in order to maintain France's competitive advantage in the luxury trades, the Saint-Simonians argued that France's long-term prosperity depended on following Britain into mechanized factory production.

Large Companies in Railroads, Banking, and Trade after 1850

During the years 1850–75, France effected a dual revolution in transport and banking that made possible the full maturation of merchant and finance capitalism, and the flowering of industrial capitalism.

Railroads were the work of private companies because the French government would not take a responsibility for building railroads similar to the responsibility it had taken for roads or canals. The Alsatian industrialist Nicolas Koechlin devoted all his wealth to building a line in 1844 from Strasbourg to Basel. A company dominated by James de Rothschild built in 1846 the line from Paris to Lille. Some Parisian bankers (the haute banque) joined with young promoters to found other railway companies. In the 1840s, only 12 percent of the railway shares being offered were actually subscribed: the government refused to guarantee a minimum return on their bonds. In January 1848, France had only 1,860 km of rail line as against 5,900 in Great Britain. But after the election of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte as president of the Second Republic, the government reconceived the legal basis for railroad construction. The extension of concessions to ninety-nine years gave more time to recoup investments, and the French state now guaranteed interest on railroad bonds. In less than twenty years, France built a world-class network. Capitalized at 400 million francs and operating 4,010 km of line, the Paris-Lyons-Marseilles (PLM) company, under the direction of Paulin Talabot, was the largest corporation in France.

After 1850, a cohort of Saint-Simonian bankers founded a new kind of joint-stock investment bank, which transformed France's financial landscape (Stoskopf 2002, 44–48). The Saint-Simonians had concluded that the most efficient way to mobilize capital was to set up limited-liability joint-stock companies that could issue shares or bonds in denominations small enough to draw the savings of the middle class. Under the French commercial code, in effect since 1808, such a company required the approval of the Conseil d'Etat. But Louis Napoleon favored such companies, and in1867 their creation became totally free.

The decisive step toward transforming the banking system was the foundation of the Crédit Mobilier in 1852. This bank, under the brothers Emile and Isaac Pereire (from the Jewish community of Bordeaux), mobilized unprecedented amounts of capital to launch an array of subsidiaries in France: railroads (the PLM among others), steamship lines, insurance companies, engineering and construction firms, industrial enterprises, and so on. It also led to the creation of a whole phalanx of new joint-stock banks. These promoted industrialization not only in France but in all continental Europe. In the financial downturn of 1866–67, the brothers Pereire took heavy losses and were obliged to shrink their company considerably.

In the meantime, however, other joint-stock banks had won official approval: The first was the Comptoir d'Escompte de Paris, founded in 1848 with semipublic status and converted in 1854 into a conventional joint-stock institution specializing in overseas trade (Bonin 1991). The second, Crédit Industriel et Commercial, was created in 1859 to finance the daily movement of goods by discounting bills of exchange and warehouse warrants. It then moved into financing overseas trade, especially in Asia, which led to the founding in 1875, in collaboration with the Comptoir d'Escompte, of the Banque d'Indochine (Meuleau 1990). A third, destined to be even more important than the others, was the Crédit Lyonnais, the only one of these originating outside of Paris, founded by silk merchants and local bankers from Lyons and Geneva. Its Paris branch soon overshadowed the home office and became in 1882 the bank's headquarters. A fourth, the Société Générale, was founded in 1864. Once launched, it moved beyond investment banking into deposit banking, leading to a large network of branches in Paris and throughout the country. Finally we have the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, founded in 1872 by the merger of two Paris firms. This bank did not aim at the larger public, but rather at a select clientele of investment bankers, moving them from family capitalism into a corporate age. It was in effect France's first banque d'affaires (investment bank).

In 1860 the French government, following the advice of the Alsatian industrialist Jean Dollfus, felt France strong enough to sign a free-trade treaty with Great Britain. This constituted a major change from generations of high protection. This treaty was followed by others with European neighbors. France was the second exporter of manufactures in the world behind Great Britain. Most of these were silk and woolen textiles and the so called articles de Paris: jewels, perfumes, fashions, furniture, and other luxury articles.

The Employers of the Second Industrialization (1870–1940)

Economic Deceleration, 1870–1880

French industry suffered much from the great depression of the end of the nineteenth century, yielding a hecatomb of small companies using the traditional techniques. Some of these firms were using methods that went back to the time of proto-industrialization. Normandy and Picardy saw decline accelerate (Cailly 1993; Barjot 1991; Chaline 1982; Leménorel 1988; Armengaud 1960; Terrier 1996; Johnson 1995). In addition, until the nineties, the government was financing important military expenses and covering its budget deficit by loans that diverted French savings from business. The Paris joint-stock banks were more and more operating abroad (in eastern Europe, the Mediterranean countries, South America, and so on) and seemed to be losing interest in French enterprise. Yet, as Maurice Lévy-Leboyer (1977a) has shown, the resources invested abroad were in the long run smaller than the incomes they earned. The most important factor of this period is labor hoarding by agriculture (some 40 percent of the French workforce before World War I and yet more than a third before World War II). This was only partly made up by foreign immigration. Even so, modernization of French capitalism continued.

Modernization of French Capitalism

After 1890, the state issued fewer bonds, leaving more room for business investment. Except for the wartime years, the period from 1890 to 1930 was one of rapid growth for French capitalism. The banks financed the industrial firms more and more (Bussière 1995). The failure of the Paris joint-stock banks to support home industry was offset by the activities of a new generation of investment and regional banks.,1 But industrial growth met new obstacles: a tougher, more contentious labor movement; and growing criticism by intellectuals.

THE GROWTH OF LARGE INDUSTRIAL FIRMS

Entrepreneurship was dynamic in a few regions. In Lorraine and the north, the iron industry was growing fast. In the Franche-Comté, industry moved to clocks and automobiles (Daumas 2004a; Olivier 2004; Lamard 1988, 1996). Around Paris we find a diversity of manufactures (autos, chemicals, electrical engineering). The same for Lyons: autos, chemicals, photography. Ports like Marseilles (Raveux 1998; Chastagnaret and Mioche 1998), Le Havre, and Nantes (Pétré-Grenouilleau 2003) processed raw materials.

And so in the late nineteenth century, France built up a roster of large corporate enterprises that would dominate the home economy and project France's influence throughout the world. Many of these companies were founded after 1890, especially in such new industries as autos, electrical engineering, and chemicals. For autos, we have Berliet at Lyons, Peugeot near Montbéliard, Citroen and Renault in Paris (Fridenson 1998; Schweitzer 1992; Fridenson 2001; Moine 1989; Baudant 1980). They had their own funds and good bank credit. They also found eager customers. There was a great incentive to use this new invention in France, because the good quality of the main roads made it possible to drive fast. In February 1899, the brothers Marcel and Fernand Renault created their auto company. In 1905, the firm received an order for 250 taxis, the beginning of mass production. In 1919, the company reorganized on the American model and limited subcontracting to a minimum. And in 1937, the brothers opened a large plant in Boulogne-Billancourt, a suburb of Paris (Fridenson 1998; Loubet 1990, 1999, 2001; Gueslin 1993). French autos proved popular abroad as well as at home: until 1929 France was the biggest car exporter in the world. France was a leader in other industries as well. At Lyons, the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumiere invented the cinematograph in 1895. To develop and exploit this invention, they helped to found the Pathé cinematograph company which made movies for the general public. In 1904, they founded their first foreign subsidiary, Lumiere North America. Other big firms were Air Liquide (Jemain 2002), Fougerolle and Eiffel (civil engineering) (Barjot 1989, 1992, 1993, 2003), Gillet (artificial silk), the Bon Marché and other big retail stores. Gustave Eiffel and Maurice Koechlin finished their Paris tower in time to commemorate the first centenary of the Revolution. The relatively high price of coal in France gave an incentive to develop the technologies of hydroelectricity. Péchiney became an important firm in electrometallurgy (Barjot, Morsel, and Coeuré 2001; Vuillermot 2001; Joly et al. 2002; Le Roux 1998; Torres 1992; Smith 2001).

Although French capitalism was planting itself in eastern Europe, Africa, and Asia (Bonin 1987), French firms were still smaller than American, British, or German ones. The biggest French company, Saint-Gobain (glass and chemicals) amounted to a twentieth of U.S. Steel. Schneider, which made arms and weapons, equaled a fifth of Krupp; Thomson-Houston a sixth of Siemens (Verley 1994, 194).

The French big businesses called more and more on outsider engineers and managers to direct the enterprise (Meuleau 1995). After World War I, more than half of the managers of big enterprises were graduates of engineering schools (Lévy-Leboyer 1979, 152; Thépot 1985; Belhoste 1995). The high level of the new techniques and the cooperation between government and the private sector during the war accelerated this tendency in the 1920s.

GROWTH AND SPECIALIZATION IN BANKING

The banking sector offered an ever-wider array of services to their expanding clientele. Before World War I, the Crédit Lyonnais had become the biggest bank in Europe (Cassis 1997, 240–47). The Paris joint-stock banks were operating increasingly outside the country. They financed foreign governments and serviced French business abroad. They were the strongest banks in eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, and South America. But they were weak in the biggest and most expansive market, the United States. A long-standing criticism is that, after 1873, they deprived the home economy of resources by putting money in unproductive foreign loans. But historians are now inclined to see this as a response to declining home demand for railroads and other public installations and have shown that between 1873 and 1914, the yield on external investments widely surpassed the total of foreign investments (Lévy-Leboyer 1977b). Besides, this failure of Paris banks to support home industry after 1870 was offset by a new generation of investment banks such as the Banque Suisse et Francaise (which later became the Crédit Commercial de France) and by regional banks (Lescure and Plessis 2004).

MODERNIZATION IN THE COMMERCIAL SECTOR

Wholesale trade was largely transformed by the rise of specialized commodity traders in staples and industrial raw materials, and of middlemen trading in manufactures. Paris and big provincial cities saw the installation of department and chain stores. The most famous was Le Bon Marché, founded in 1872 by Aristide Boucicaut, established in the world's largest commercial structure. Costs were cut by sending buyers directly to manufacturers. In some cases (ready-made clothing), the grands magasins became their own manufacturers and suppliers.

New Obstacles to the Entrepreneurship in France after 1870

THE NEW REPUBLICAN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP

During the Second Empire, the high bourgeoisie was very active politically, and some entrepreneurs sat in the Parliament. Under the Third Republic, representatives of the liberal professions and public officials took their place. Ignorant of the needs imposed by international competition and afraid of fast industrialization, they led the French electorate to fear big business. The parti radical, which became the leading political party at the start of the twentieth century, made it its goal protection and preservation of small producers. It became a force for economic conservatism, but it also promoted the creation of many small firms. Before World War I, France, a nation of small farms, knew millions of these tiny industrial units, many of them individual entrepreneurs. In 1906, 71 percent of the plants in the craft and industrial sector were individual enterprises, employing 21 percent of the industrial workforce. The domestic system continued to dominate industries like clothing. In 1935, the French government protected small shops by discouraging the creation of supermarkets. In this way, France remained a nation of small independent producers—not efficient perhaps, but socially egalitarian.

A RIGHTIST ANTICAPITALISM: ANTI-SEMITISM

The great industrial families were resented by the reactionary elements of French society. The big employers were often members of religious minorities, Protestant or Jewish. Their attempts to enter the social elite, for example the corps of army officers, met with resentment and hostility. This was the making of the infamous Dreyfus affair, in which a French officer from a Jewish entrepreneurial family was unjustly accused and convicted of spying for Germany. The French found it hard to understand the quick enrichment of Protestant and Jewish families, just as they found it hard to comprehend the fast rise of German power, or of the Anglo-Saxon countries. French reactionaries were quick to blame France's loss of power and position on the supposed defects of republican government. Anti-Semitism gave force to this attitude by blaming failings on the Jews.

ANARCHISM AND MARXISM

French trade unionism was invested in the 1880s by revolutionaries, often of anarchistic inspiration. They thought industrial disputes should aim less at limited improvement than at major confrontations with the bourgeoisie. This attitude substantially radicalized labor relations. In those areas where workers lived—harbors, mining basins, city suburbs—labor relations grew embittered. Strikes and violence reached a peak in 1906. But the strikes of 1936 proved more costly to employers because the workers occupied the factories and mills and the government (the Front Populaire) did not intervene against these occupations.

Anticapitalism of the left also spread in intellectual circles. From the 1890s teachers at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, who set the tone among French intellectual elites, spread a climate of hostility to businessmen, especially the richest of them, called by the Left les 200 familles, and accused of them of undermining the French currency as a way of discrediting the leftist government.

A Withdrawal into the Home Market

The second industrialization of France proceeded in a difficult social and economic context. Growth had slowed after 1860, owing to decline of the birthrate, the narrowness of the home market, and the swollen, unproductive agricultural sector. After World War I, mass production suffered from inadequate demand. The standard of living was half the American, and 70 percent of the population lived in small towns and villages of less than 20,000 inhabitants (Lévy-Leboyer 1996, 18).

After 1871, industry also suffered from the loss of Alsace and its enterprising businessmen. Some of these re-created industrial firms in the Vosges or in Normandy, but most of them were lost to Germany. Some left for other countries—thus Koechlin to Switzerland and Schlumberger to France and America. But the defeat of 1871 diverted many brave children of these families to military careers. With the Alsatians gone, the most conservative elements of the French patronat regained their influence. The free-trade treaties of the 1860s were called into question by employers' associations (Lambert-Dansette 2000, 136). The spirit of protection returned. But the big companies remained, open to the larger world. The biggest handicap for industrial exporters came from agricultural protectionism. Thus concern for grape growers blocked industrial agreements with the countries of eastern and southern Europe and left the field to German exporters (Poidevin 1995).

The Golden Age of Dirigisme (1940–1983)

Bases of French Neo-Colbertism

From the 1930s French industrial investment shrank sharply. Capacities for modernization were much reduced. Meanwhile the new dictatorships in Nazi Germany, fascistic Italy, and Soviet Russia boasted of real or alleged achievements. Would-be French “modernizers” denounced the real or supposed routine of family capitalism, calling for an alliance of big business and the state and even a recourse to economic planning. The defeat of 1940 gave these modernizers access to power. Many served the Vichy regime and only later joined the Resistance (if they ever did), so that the Liberation regime was on many points continuing actions and programs begun under Vichy.

The Liberation regime was the product of a compromise between the two greatest Resistance forces, the Gaullists and the Communists. The latter gave up their arms in exchange for a wide program of business nationalization and control of major public-sector trade unions. This public sector, in turn, controlled such areas as scientific research, education, coal mining, the press, output of electricity, rail transports, seaports, and postal and telephone services.

Coal, electricity, gas, nuclear energy, oil, railroads, aeronautics, most of the big Parisian banks and the Renault auto plants were nationalized. This pleased the “modernizers,” who thought that only the state could promote modernization (Andrieu and Van-Lemesle 1987; Kuisel 1984; Picard, Beltran, and Bungener 1985; Jeanneney 1959; Desjardins et al. 2002). At the head of the nationalized companies, the government placed graduates of the engineering schools, new young elites, aspirants to social progress.

A four-year plan (after 1966, five-year plans) made it possible for French businessmen to pursue their goals for development. And after the fifth plan (1966–70), the growing importance of international trade freed French firms from dependence on the plan, whose aims concerned above all domestic demand.

Constraints on Private Firms

From 1945, taxes weighed heavily on private firms, which largely paid the cost of the new social security: family allowances, accident insurance, health and old age coverage, contributions to transport and housing costs; plus, after 1958, unemployment insurance and, after 1971, contribution to employee training.

The government now held a wide range of financial instruments for intervening in the economy. Price controls were instituted from 1939, with opportunities for dialogue between businesspeople and the administration. Credit control was also introduced with the nationalization of the Banque de France, of the four big deposit banks, and of the major insurance companies. Note also that the state controlled other financial establishments: the Caisse des Dépots et Consignations, which manages the deposits of notaries and savings banks (Aglan, Margairaz, and Verheyde 2003); the Crédit National (created in 1919 for reconstruction); the Crédit Foncier de France; and the Crédit Agricole. Finally, in 1948, the state created the Fonds de Modernisation et d'Equipement to allocate Marshall Plan aid. This fund was supplemented after 1955 by the state-financed Fonds de Développement Economique et Social. In this way, the Ministry of Finances, heart of the French administrative elite, was able to direct much of the country's investment (Quennouëlle-Corre 2000). Railways, electricity, and coal mines received huge, state-of-the-art equipment. French trains became some of the fastest in the world and the power stations of Electricité de France some of the most productive.

By comparison, private financing was weak. Price control hurt, and in contrast with the 1920s, the stock exchange did little. French companies had little recourse to new shares or bonds because of monetary depreciation and the competition of government loans. So only bank financing was left. After 1945, the preferred choice was medium-term (five years) credit. French companies were financially fragile.

The socialist nationalizations of 1981 moved more capital into government hands. The state share of the industrial labor force went from 6 percent to 19 percent, and it controlled 90 percent of bank deposits. Now the state controlled thirteen of the twenty biggest companies in the country. The state increased the capital of these companies and subsidized those in difficulty: Bull, Rhone-Poulenc, Thomson, Pechiney, and so forth. At its maximum in 1985, government share of the capital of the French companies was 10 percent.

French Entrepreneurship, 1940–1983

French employers were not afraid of decolonization (Marseille 2004; Eck 2003; Fridenson 1994). But they were worried about lower customs duties and the elimination of import quotas, which left them in naked competition with a German industry paying lower social contributions and taxes. As in 1860, a goodly share of French employers, above all the heads of small firms, were opposed to lower protection. When in 1959, General de Gaulle, in fulfillment of treaty obligations, instituted free currency convertibility, an end to import quotas, and a first fall in the customs dues, he made a lot of people unhappy.

Big business continued to be tied to the state, where it found its top executives (some thousands of individuals) (Bauer and Bertin-Mourot 1997) recruited from the top engineering schools.2 This was the French ruling class. It had known defeat in 1940 and shared the point of view of the historian Marc Bloch: “What was defeated is our dear small town” (Bloch 1995, 182; Daumard 1987, 380). France had not been enough industrialized to face successfully the new German army. Now it was time to catch up with other advanced countries, to make up for lost time. Georges Pompidou, prime minister from 1962 to 1968 and president of the Republic from 1969 to 1974, then Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, president from 1974 to 1981, were part of this meritocratic, ambitious world, because they resulted quite from the same meritocracy (Ecole Normale Supérieure was Pompidou's school and Polytechnique was that of Giscard d'Estaing) (Fridenson 1997, 219). None saw any reason for economic growth to slow. In a revival of Saint-Simonian spirit, Pierre Massé, commissaire au Plan (chief of the Planning Commission), optimistically anticipated: “The mean standard of living can double in twenty years and perhaps even faster if our mastery of technology and economics continues to grow” (Massé 1965, 89).

During World War II, French industrial technology seriously lagged. From 1948, French engineers and entrepreneurs made organized five-week trips to the United States to learn new production and management techniques (Barjot 2002). During the 1950s, 267 such productivity missions comprised some 2,600 participants. After 1960, the continuing flow of American investment entailed transfer of American economic and technical methods to France.

Indeed, the years of the Pompidou government and presidency saw France's most brilliant economic performance ever. Between 1962, when France rid itself of the burden of war in Algeria, and 1974, when it ran into its first oil crisis, gross domestic product grew 5.2 percent in annual average. Many left agriculture for industry: during the 1970s, the agricultural sector fell to under 10 percent of the workforce. Engineers confidently made plans, with the confidence that the state would help carry them out. State and elites had grand visions. The generations formed just before the war or during the German occupation were reacting against the narrow vision of their predecessors. So France in 1969 saw the launching of the Airbus, the first flight of the supersonic Anglo-French Concorde, and the first two experimental cars of the high-speed train (TGV) (Lachaume 1986). In 1971, the first entirely digitalized phone exchange began operation in the Breton town of Perros-Guirec. And 1973 saw the start of the European space launcher Ariane.

That same year, a European agreement led to creation in France of a factory for uranium enrichment for civil reactors. This was followed by construction of nuclear power stations, to the point where France was getting three-quarters of its electrical supply from this source—more than any other country. The French firm Framatome (later renamed Areva) became a rival of Westinghouse on the international market. That was France's answer to oil crisis (Beltran 1985).

The Policy of Creating “National Champions”

Meanwhile the French government encouraged mergers to build larger companies, “national champions” of European (continental) size. The aim was to defend French firms against foreign penetration, and the result was the formation of diversified conglomerates. In oil, the merger of several state-owned firms led to the creation of Elf. In banking, the fusion between the Banque Nationale pour le Commerce et l'Industrie and the Comptoir d'Escompte de Paris gave the Banque Nationale de Paris; at the same time the big Parisian banks took over most of the regional banks. In chemicals, the Office National de l'Azote joined with the Potasses d'Alsace to create the Entreprise Miniere et Chimique. In the same way, at the beginning of 1968, a score of small insurance companies created three big groups of European dimensions. The iron and steel industry was soon gathered into two units, Sacilor in the east and Usinor in the north. In electrical engineering, one had the Cie Générale d'Electricité; in telecommunications Alcatel; in electronics Thomson; in aeronautics Aérospatiale (Fridenson 2006b). But these national champions built primarily on size. They paid less attention to competitive choice of investments.

Meanwhile organizational and regulatory innovations (introduction of leasing, creation of a mortgage market, suppression of the exchange control) helped the French financial system make up for lost time. The innovator here was Michel Debré, minister of finance from 1966 to 1968. When France abolished the distinction between deposit and investment banks, it put its financial sector on a better basis than those of its neighbors, except for that of the United Kingdom. Yet the money market remained stodgy: too much of it rested on bond issues—some 70 percent in 1970. For all this period, the money market generated only 10 percent of company finance.

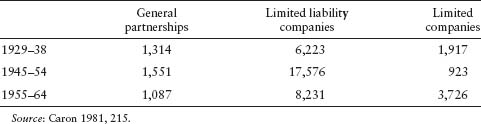

TABLE 11.1

Annual Mean of Creations of Companies

This pattern of state-controlled development did well until 1974. In that year, output per man-hour was higher in France than in Federal Republic Germany or in Great Britain. No wonder French elites stuck to these arrangements (Maddison 2006, 353). Besides, they liked the power and place state control gave to them as elites.

The Rise of a Capitalism Independent of the State

Is this to say there was no autonomous capitalism in those years? No. A private sector emerged in the manufacture and sale of consumer goods. Thus, with bank support, we have a new agribusiness in the agricultural and food sector (Bonin 2005). The Danone group was originally created by Gervais and then bought up by the glass group Boussois-Souchon-Neuvesel. Similar new groups were to be found in building and public works, chemicals, and beauty products. An example is L'Oréal, which began by making scented soaps. Moulinex and SEB specialized successfully in small household electrical devices (Seb 2003; Gaston-Breton and Defever-Kapferer 1999; Pernod-Ricard 1999). In autos, Peugeot repurchased Citroen to form the PSA group. All of these companies had extensive recourse to advertising. Such performances call into question the negative appraisal of French small and medium-size companies.

In retail trade, the restrictive legislation protecting small shops was gradually annulled after 1959. Big supermarkets, like Leclerc and Carrefour, appeared. And then the latter invented the biggest form of commercial organization: the hypermarket.

With these new trade giants came a decline in general partnerships and growing recourse to limited liability. The vitality of this capitalism showed in the boom of small enterprises in the years 1945–54, and the boom in limited companies after 1955.

Back to Liberalism (from 1983 to Today)

The Withdrawal of the State

After 1981, the socialist government of François Mitterrand intervened in the economy more than ever. It nationalized the last independent private banks and most of the big industrial firms. But the nationalized firms did not make money and needed more and more state support (Cohen 1989). The debts of the national railways (SNCF) and power supply system (Electricité de France) kept going up, in spite of public subsidies. These nationalized firms created few jobs, and their managements made big mistakes. The worst was the Crédit Lyonnais, which lost a fortune and had to pay a record fine of one billion dollars because of failure to observe American regulations. All of this sounded the knell of Socialist industrial policy.

The turning was March 1983, with the socialists still in power. Faced with rising deficits and a disastrous fall in the exchange value of the franc, the government abandoned its active economic interventionism. The effects were gradual, but the French economy now lined up with those of the liberal economies of western Europe. In 1984 financial circuits were freed up, and wages were no longer indexed on prices. The share of value-added going to wages reached a maximum of 68 percent in 1983, then fell fast to less than 60 percent. In 1984, the metallurgical group Creusot-Loire had huge losses. This was the largest French group in fine steel and machinery and employed 23,000 workers. After much hesitation, the government decided to abandon support, and the group failed financially in 1984.

The elections of 1986 brought the Right back to power. It decided on full price freedom and took the state out of thirteen big financial and industrial firms, including all the banks nationalized in 1945. Carmaker Renault was privatized in 1994. The public financial sector was now limited to the Caisse des Dépots et Consignations, still powerful, and the Post Office. With the launch of the euro in January 1999, France entered European financial circuits.

Even so, the state tried to create two business groups: one composed of the Banque Nationale de Paris, Elf, Saint-Gobain, Pechiney, Suez, and the Union des Assurances de Paris, the other of the Assurances Générales de France, Alcatel, Havas, Paribas, Rhone-Poulenc, the Société Générale, and Total. But this system based on cross participations immobilized large sums and led to undercapitalization of these firms, preventing further mergers and growth. Things broke down in the midnineties. Once again shareholders broke away.

Foreign investors now moved in. By the end of 1999, a little more than half the authorized capital of the largest French firms was held by foreigners (Morin and Rigamonti 2002). Selecting privatization had aimed at protecting French firms from outside takeovers, but it had the opposite effect: it had weakened their capitalization and made them targets. Today France is one of the countries most open to foreign capital. Between 30 and 50 percent of such firms as the Banque Nationale de Paris, the Societé Générale, Alcatel, Axa or Vivendi were in foreign hands in 2005. In 2006 the French government had no way to prevent the Anglo-Indian businessman Mittal from controlling Arcelor, the biggest European steelmaker, built by a merger of firms from France, Luxembourg, and Spain.

Triumph of the Financial Markets

Helped by international economic circumstances, French stock exchange prices were multiplied by four from 1981 to 1987. This was followed by another rise in the 1990s. The stock exchange, which accounted for only 27 percent of the financing of the French economy in the 1980s, accounted for 80 percent in 1997. France was not ready for this revolution. Savings accounted for 15 percent of GDP, but the state diverted them to debt finance. This left the field free to foreign institutional investors. Meanwhile, French institutional investors, like insurance companies, preferred government loans.

Thanks to greater financial freedom, French companies could reduce debt, reinforce capital, and engage in self-financing. Big firms adapted well and began to play a role on world markets. French owners could move freely, globalize, and develop subsidiaries around the world. In 2005, 40 French multinationals were among the first 500 in the world. Among the leaders: LVMH (luxuries) L'Oréal (cosmetics), Danone (dairy products), Vinci (civil engineering), Vivendi (film, music, publishing), Veolia (water treatment), Air France, Areva (nuclear), Air Liquide (industrial gas) or Essilor (eyeglasses). The French did well in publishing, data processing (Marseille and Eveno 2002; Gaston-Breton 1997), hotel trade (Luc 1998), luxury articles (Bergeron 1998; Marseille 1999; Ferrière 1995; Dalle 2001; Dubois 1988), energy engineering, transportation (Barjot 1992, 1993, 2003), or large-scale distribution (Villermet 1991; Chadeau 1995; Petit, Grislain, and Le Blan 1985). American and British investment funds set the example, and French firms were quick to react to market signals in the field of finance. One saw a new type of entrepreneurs, from elsewhere in the world, open to the world. An example is Carlos Ghosn, chairman of Renault. Of Lebanese origin, born in 1954 in Brazil, student at Polytechnique in Paris, he succeeded in 1999 in merging Renault with Nissan and in 2005 became president of the joint company.

The enormous power of the chairmen, characteristic of the French model, was now free of government constraints but responsive to the increasing influence of shareholders. Financial logic in the short run displaced industrial logic in the long run (Trumbull 2004; Fridenson 2006a).

The Persistence of Family Capitalism

The risk of strikes and the load of administrative constraints (such as the thirty-five-hour week, the complexity of the fair labor standards act, corporation taxes, social contributions) continue to discourage company formation in France. France is the European country where creation of companies is seen as most difficult. That is why so many French are now living and working abroad. For example, 200,000 or more live today in London.

During these last years, administrative difficulties have much diminished. Formalities have been regrouped, social security taxes reduced. French companies have moved toward the Anglo-Saxon model and there is more private shareholding. In 2003, 7.2 million French held company shares (one household on four), more than the number of trade unionists. The west of France (Bretagne, the Vendée, Mayenne) is experiencing an economic revival, with much cooperation among medium and small enterprises (Lescure 2002).

Conclusion

France has inherited two traditions: On the one hand, that of a controlled economy led by a monarchical state or later by socialist ideology; on the other, that of market capitalism, especially strong in regions (north and east) and among religious groups (Protestants and Jews) tardily integrated into the larger society.

The administrative and political power of the strongly centralized French state never prevented a substantial group of innovative entrepreneurs from promoting industrialization and technical progress in France. State institutions founded by the Monarchy at the end of the eighteenth century or by the Revolution helped the dissemination of inventions among French manufacturers. But the initiatives came above all from the entrepreneurs. Northern and eastern France as well as Paris were the regions or places where entrepreneurs were the most innovative. It seems that traditions of urban self-government and independence from the centralized state stimulated entrepreneurship.

The role of innovating entrepreneurs was essential in the process of industrialization. Many of the inventors were also industrialists developing each innovation and making it practical for the end-user. For instance, the French locomotive-constructors made engines more coal-sparing than the British, adapting their models to the conditions of a country with expensive coal. Another example is that of the brothers Lumiere: they invented the cinematograph and they helped to found a company to make movies for the general public.

After the Revolution, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, entrepreneurs reached the first rank in the French society. The wealth of the richest entrepreneurs surpassed soon that of the biggest landowners and, after 1830, they were influential at the highest level of the state. But their social climbing was criticized by other elites such as the old aristocracy, and the new intellectual and artistic elites. The process of industrialization itself was disapproved of by a part of public opinion. Until to World War II, many deputies in the French Parliament were reticent about the development of large-scale industry and the growth of vast worker concentrations. The impediments against the diffusion of entrepreneurship in France came above all from right- or left-wing extremists. During the nineteenth century, a part of the elites preferred to pursue a career in public office or in the army rather than enter private industry. But increasingly, things began to change. During the twentieth century, high civil service officers and entrepreneurs, belonging to the same meritocracy, coming from the same engineering schools, merged in a unique ruling class. This trend accelerated after World War II: the French state played an important role in order to promote new technologies, financing huge investments in energy and transports.

Between 1940 and the middle of the 1980s, the political and administrative elites chose the model of a state-controlled economy and tried to develop large national firms. This tendency was reinforced during the first years of socialist government under the presidency of François Mitterrand, from 1981 to 1983. But, after 1983, the French government decided to abandon interventionist policy and returned slowly to liberal rules.

Today it would seem that entrepreneurship in France enters in a new era: entrepreneurs have greatly gained in power. In twenty years, the country has passed from state capitalism to market capitalism. The postwar legacy of “national champions” sees French multinationals working like foreign multinationals. New enterprises have now appeared and are growing. Their biggest task is to grow fast enough not to remain small.

Notes

1 Banque de l'Union Parisienne, Banque Suisse et Française (later renamed Crédit Commercial de France), Banque Internationale de Paris (later renamed Banque française pour le Commerce et l'Industrie), etc.

2 Jean Meynaud estimated their number at 5,000–6,000 (1964, 165).

References

Aerts, Erik, and François Crouzet, eds. 1990. Economic Effects of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars: Proceedings of the Tenth International Economic History Congress. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Aglan Alya, Michel Margairaz, and Philippe Verheyde, eds. 2003. La Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations: La Seconde Guerre mondiale et le XXe siècle. Paris: Albin Michel.

Albert, Michel. 1991. Capitalisme contre capitalisme. Paris: Le Seuil.

Amable, Bruno. 2005. Les Cinq capitalismes: Diversité des systèmes économiques et sociaux dans la mondialisation. Paris: Le Seuil.

Andrieu, Claire, and Le Van-Lemesle Lucette, eds. 1987. Les nationalisations de la Libération: De l'utopie au compromis. Paris: Presses de la Fondation nationale des Sciences politiques.

Angleraud, Bernadette, and Catherine Pélissier. 2003. Les dynasties lyonnaises. Paris: Perrin.

Armengaud, André. 1960. “A propos des origines du sous-développement industriel dans le Sud-Ouest.” Annales du Midi 1:75–81.

Asselain, Jean-Charles. 1984. Histoire économique de la France du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours. 2 vols. Paris: Le Seuil.

Barbier, Frédéric, ed. 1989. Le patronat du Nord sous le Second Empire. Une approche pro-sopographique. Geneva: Droz-Champion.

Barjot, Dominique. 1989. La grande entreprise française de travaux publics, 1883–1974. Lille: A.N.R.T, Université de Lille III.

———, ed. 1991. Les patrons du Second Empire. Anjou, Normandie, Maine. Paris: Picard.

———. 1992. Fougerolle. Deux siècles de savoir-faire. Caen: Editions du Lys.

———. 1993. Travaux publics de France. Un siècle d'entrepreneurs et d'entreprises. Paris: Presses de l'Ecole des Ponts-et-Chaussées.

———, ed. 2002. L'americanisation de l'Europe occidentale au XXe siècle: Mythe et réalité. Paris: Presses de l'Université de Paris–Sorbonne.

———. 2003. La trace des bâtisseurs. Histoire du groupe Vinci. Vinci: Rueil-Malmaison.

Barjot, Dominique, Eric Anceau, Isabelle Lescent-Gilles, and Bruno Marnot, eds. 2003. Les entrepreneurs du Second Empire. Paris: Presses de l'Université de Paris–Sorbonne.

Barjot, Dominique, Henri Morsel, and Sophie Coeuré. 2001. Les compagnies électriques et leurs patrons. Stratégies, gestion, management, 1895–1945. Paris: Fondation Electricité de France.

Baudant, Alain. 1980. Pont-à-Mousson (1918–1939): Stratégies industrielles d'une dynastie lorraine. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne.

Bauer, Michel, and Bénédicte Bertin-Mourot. 1987. Les 200. Comment devient-on un grand patron? Paris: Seuil.

———. 1997. L'ENA est-elle une business school? Paris: L'Harmattan.

Belhoste, Bruno, ed. 1995. La France des X, deux siècles d'histoire. Paris: Economica.

Beltran, Alain. 1985. Histoire de l'EDF. Comment se sont prises les décisions de 1946 à nos jours. Paris: Dunod.

Beltran, Alain, Jean-Pierre Daviet, and Michèle Ruffat. 1995. L'histoire d'entreprise en France. Essai bibliographique. Paris: Institut d'histoire du temps présent.

Bergeron, Louis. 1998. Les industries du luxe en France. Paris: Odile Jacob.

Bloch, Marc. 1995. L'étrange défaite. Paris: Folio Histoire.

Bonin, Hubert. 1985. “La Révolution a-t-elle brisé l'esprit d'entreprise?” L'Information historique 5:193–204.

———. 1987a. CFAO (Compagnie française de l'Afrique occidentale). Cent ans de compétition (1887–1987). Paris: Economica.

———. 1987b. Suez. Du canal à la finance (1858–1987). Paris: Economica.

———. 1991. “Le Comptoir d'Escompte de Paris: Une banque impériale, 1848–1940.” Revue Française d'Histoire d'Outre-Mer 78:477–97.

———. 1992. Une grande entreprise bancaire: Le Comptoir national d'escompte de Paris dans l'entre-deux-guerres. Paris: Comité pour l'Histoire économique et financière.

———. 1995. Les groupes financiers français. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

———. 1999. Les patrons du Second Empire. Bordeaux et la Gironde. Paris: Picard.

———. 2001. La Banque de l'Union Parisienne. Histoire de la deuxième banque d'affaires française (1874/1904–1974). Paris: P.L.A.G.E.

———. 2005. Les coopératives laitières du grand Sud-Ouest (1893–2005). Paris: P.L.A.G.E.

Breton, Yves, Albert Broder, and Michel Lutfalla, eds. 1997. La longue stagnation en France. L'autre grande dépression, 1873–1897. Paris: Economica.

Bussière, Eric. 1992. Paribas, l'Europe et le monde, 1872–1992. Anvers: Fonds Mercator.

———. 1995. “Paribas and the Rationalization of the French Electricity Industy, 1900–1930.” In Management and Business in Britain and France: The Age of the Corporate Economy, ed. Youssef Cassis, François Crouzet, and Terry Gourvish, 204–13. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Butel, Paul. 1991. Les dynasties bordelaises, de Colbert à Chaban. Paris: Perrin.

Cailly, Claude. 1993. Mutations d'un espace proto-industriel: Le Perche aux XVIIIe–XIXe siècles. Lille: A.N.R.T, Université de Lille III.

Cameron, Rondo. 1971. “L'esprit d'entreprise.” In La France et le développement économique de l'Europe, 1800–1914. Paris: Le Seuil.

Carlier, Claude. 1992. Marcel Dassault: La légende du siècle. Paris: Perrin.

———. 2003. Matra, la volonté d'entreprendre. De Matra à EADS. Paris: Editions du Chêne-Hachette.

Caron, François. 1981. Histoire économique de la France XIXe–XXe siecles. Paris: Armand Colin.

———, ed. 1983. Entreprises et entrepreneurs XIXe–XXe siècles. Paris: Presses de l'Université Paris–Sorbonne.

———. 1995. Histoire économique de la France, XIXe–XXe siècles. 2nd ed. Paris: Armand Colin.

Carter, Edward C., ed. 1976. Enterprise and Entrepreneurs in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century France. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Cassis, Youssef. 1997. Big Business: The European Experience in the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cassis, Youssef, François Crouzet, and Terry Gourvish, eds. 1995. Management and Business in Britain and France: The Age of the Corporate Economy. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Caty, Roland, Eliane Richard, and Pierre Echinard. 1999. Les patrons du Second Empire. Marseille. Paris: Picard.

Cayez, Pierre. 1988. Rhône-Poulenc, 1895–1975. Contribution à l'étude d'un groupe industriel. Paris: Armand Colin-Masson.

Cazes, Bernard, and Philippe Mioche. 1990. Modernisation ou décadence. Contribution à l'histoire du Plan Monnet et de la planification en France. Aix-Marseille: Publications de l'Université de Provence.

Chadeau, Emmanuel. 1987. L'industrie aéronautique en France, 1900–1950. Paris: Fayard.

———. L'économie du risque. 1988. Les entrepreneurs de 1850 à 1980. Paris: Olivier Orban.

———. 1995. “Mass Retailing: A Last Chance for the Family Firm in France, 1945–1990?” In Management and Business in Britain and France: The Age of the Corporate Economy, ed. Youssef Cassis, François Crouzet, and Terry Gourvish, 52–71. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Chaline, Jean-Pierre. 1982. Les bourgeois de Rouen: Une élite urbaine au XIXe siècle. Paris: Presses de la FNSP.

———. 1988. “Idéologie et mode de vie du monde patronal haut-normand sous le Second Empire.” Annales de Normandie, May–July.

Chassagne, Serge. 1991. Le coton et ses patrons en France, 1760–1840. Paris: EHESS.

Chastagnaret, Gérard, and Philippe Mioche, eds. 1998. Histoire industrielle de la Provence. Aix-Marseille: Publications de l'Université de Provence.

Cohen, Elie.1989. L'Etat brancardier. Politiques du déclin industriel (1974–1984). Paris: Calmann-Lévy.

Cohen, Elie, and Michel Bauer. 1985. Les grandes manoeuvres industrielles. Paris: Belfond.

Crouzet, François. 1959. “Les origines du sous-développement economique du Sud-Ouest.” Annales du Midi 1:1–79.

———. 1989. “Les conséquences économiques de la Révolution française. Réflexions sur un débat.” In “Révolution de 1789, guerres et croissance économique,” ed. Jean-Charles Asselain. Revue économique 40:1189–1203.

Dalle, Francois. 2001. L'aventure L'Oréal. Paris: Odile Jacob.

Darnton, Robert. 1983. Boheme littéraire et Revolution: Le monde des livres au XVIIIe siecle. Paris: Gallimard.

Daumard, Adeline. 1987. Les bourgeois et la bourgeoisie en France depuis 1815. Paris: Aubier.

Daumas, Jean-Claude, ed. 2004a. Les systèmes productifs dans l'Arc jurassien. Acteurs, pratiques et territoires (XIXe–XXe siècles). Besançon: Presses Universitaires de Franche-Comté.

———. 2004b. Les Territoires de la laine. Histoire de l'industrie lainière en France au XIXe siècle. Villeneuve d'Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion.

Daviet, Jean-Pierre. 1989. Une multinationale à la française. Histoire de Saint-Gobain, 1665–1989. Paris: Fayard.

Delsalle, Paul. 1987. Tourcoing sous l'Ancien Régime. Lille: Impr. du Siècle.

Desjardins, Bernard, Michel Lescure, Roger Nougaret, Alain Plessis, and André Straus. 2002. Le Crédit lyonnais, 1863–1986. Etudes historiques. Geneva: Droz.

Dubois, Paul. 1988. L'industrie de l'habillement. L'innovation face à la crise. Paris: La Documentation française.

Eck, Jean-François. 2003. Les entreprises françaises face à l'Allemagne de 1945 à la fin des années 1960. Paris: Comité pour l'Histoire économique et financière de la France.

Ferrière, Marc de. 1995. Christofle: Deux siècles d'aventure industrielle, 1793–1993. Paris: Le Monde Editions.

Fridenson, Patrick. 1994. “Les patronats allemands et français au XXe siècle. Essai de comparaison.” In Eliten in Deutschland und Frankreich im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Strukturen und Beziehungen, ed. Rainer Hudemann and Georges-Henri Soutou, 153–67. Munich: Oldenburg Verlag.

———. 1997. “France: The Relatively Slow Development of Big Business in the Twentieth Century.” In Big Business and the Wealth of Nations, ed. Alfred D. Chandler Jr., Franco Amatori, and Takashi Hikino, 207–45. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1998. Histoire des usines Renault. Naissance de la grande entreprise 1898–1939. 2nd ed. Paris: Le Seuil.

———, ed. 2001. Mémoires industrielles II. Berliet, le camion français est né à Lyon. Paris: Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l'Homme-Syrinx.

———. 2006a. “The Main Changes in the Behavior of French Companies in the Past 25 Years.” Bulletin de la Société franco-japonaise de gestion, May, 15–25.

———. 2006b. “La multinationalisation des entreprises françaises publiques et privées de 1945 à 1981.” In L'économie française dans la compétition internationale au 20e siècle, ed. Maurice Lévy-Leboyer, 311–35. Paris: Comité pour l'histoire économique et financière de la France.

Fridenson, Patrick, and André Straus, eds. 1987. Le capitalisme français XIXe et XXe siècles. Blocages et dynamismes d'une croissance. Paris: Fayard.

Gaston-Breton, Tristan. 1997. De Sogeti à Cap Gemini, 1967–1997. 30 ans d'histoire. Paris: CGS.

———. 1998. Lesieur. Une marque dans l'histoire, 1908–1998. Paris: Perrin.

Gaston-Breton, Tristan, and Patricia Defever-Kapferer. 1999. La magie Moulinex. Paris: Le Cherche-Midi.

Gille, Bertrand. 1959. Recherches sur la formation de la grande entreprise capitaliste, 1815–1848. Paris: SEVPEN.

———. 1968. La banque et le crédit en France de 1815 à 1848. Geneva: Droz.

Goyer, Michel. 2003. “Corporate Governance, Employees, and the Focus on Core Competencies in France and Germany.” In Global Markets, Domestic Institutions: Corporate Law and Governance in a New Era of Cross-Border Deals, ed. Curtis J. Milhaupt, 183–213. New York: Columbia University Press.

———. 2006. “La transformation du gouvernement d'entreprise.” In La France en mutation 1980–2005, ed. Pepper D. Culpepper, Peter A. Hall, and Bruno Palier, 71–108. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Groethuysen, Bernard. 1927. Les origines de l'esprit bourgeois en France. Vol. 1, L'Eglise et la bourgeoisie. Paris.

Gueslin, André, ed. 1993. Michelin, les hommes du pneu, 1889–1940. Paris: Les Editions de l'Atelier.

Hall, Peter A. 1986. Governing the Economy: The Politics of State Intervention in Britain and France. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hall, Peter A., and David Soskice. 2001. “An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalism.” In Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage, ed. Peter A. Hall and David Soskice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hancké, Bob. 2002. Large Firms and Institutional Change: Industrial Renewal and Economic Restructuring in France. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hau, Michel. 1987. L'industrialisation de l'Alsace (1803–1939). Strasbourg: Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg.

Hau, Michel, and Nicolas Stoskopf. 2005. Les dynasties alsaciennes. Paris: Perrin.

Heinrich, Nathalie. 2006. L'élite artiste. Excellence et singularité en régime démocratique. Paris: Gallimard.

Hirsch, Jean-Pierre. 1991. Les deux rêves du commerce. Entreprise et institution dans la région lilloise (1780–1860). Paris: Editions de l'Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales.

Holworth, Jolyon, and Philip Cerny, eds. 1981. Elites in France: Origins, Reproduction, and Power. London: Frances Pinter, for the Association for the Study of Modern and Contemporary France.

Hudemann, Rainer, and Georges-Henri Soutou, eds. 1994. Eliten in Deutschland und Frankreich im 19. Und 20. Jahrhundert. Strukturen und Beziehungen. Munich: Oldenburg Verlag.

Jeanneney, Jean-Marcel. 1959. Forces et faiblesses de l'économie française. Paris: Fondation nationale des Sciences politiques.

Jemain, Alain. 2002. Les conquérants de l'invisible. Air liquide, 100 ans d'histoire. Paris: Fayard.

Johnson, Christopher. 1995. The Life and Death of Industrial Languedoc, 1700–1920. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Joly, Hervé Alexandre Giandou, Muriel Le Roux, Anne Dalmasso, and Ludovic Cailluet, eds. 2002. Des barrages, des usines et des hommes. L'industrialisation des Alpes du Nord entre ressources locales et apports extérieurs. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble.

Kuisel, Richard. 1984. Le capitalisme et l'Etat en France. Modernisation et dirigisme au XXe siècle. Paris: Gallimard.

Lachaume, P. 1986. “De l'hélice à l'aviation à réaction (moteurs civils).” In Colloque de l'aéronautique et de l'espace, quarante années de développement aérospatial français, 1945–1985, 195–202. Paris: Institut d'histoire des conflits contemporains, Centre d'histoire de l'aéronautique et de l'espace.

Lambert-Dansette, Jean. 1992. La Vie des chefs d'entreprise en France (1830–1880). Paris: Hachette.

Lamard, Pierre. 1988. Histoire d'un capital familial au XIXe siècle: Le capital Japy (1777–1910). Belfort: Société Belfortaine d'Emulation.

———. 1996. De la forge à la société holding, Viellard-Migeon et Cie, 1796–1996. Paris: Polytechnica.

Lambert-Dansette, Jean. 2000. Histoire de l'entreprise et des chefs d'entreprise en France. Vol. 1. Paris: L'Harmattan.

Landes, David S. 1951. “French Business and the Businessman: A Social and Cultural Analysis.” In Modern France: Problems of the Third and Fourth Republics, ed. M. Earle, 334–53. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 1967. The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present. London: Cambridge University Press.

———.1999. The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some Are So Poor. New York: Norton.

———. 2006. Dynasties, Fortunes, and Misfortunes of the World's Great Family Businesses. New York: Viking.

Lanthier, Pierre. 1988. “Les constructions électriques en France. Financement et stratégies de six groupes industriels internationaux.” Thesis, Université de Paris X–Nanterre.