Chapter 15

An Examination of the Supply of Financial Credit to Entrepreneurs in Colonial India

IN 1968 WILLIAM BAUMOL CALLED for a renewed focus on the “determinants of the payoff to entrepreneurial activity.” Understanding the allocation of entrepreneurial talent was crucial, as “the entrepreneur is the key to the stimulation of growth.” In a 1990 paper, on a less optimistic note, he argued that an inappropriate payoff structure, one that rewards unproductive entrepreneurship, is empirically associated with very slow growth.

India, particularly colonial India, is a fascinating case study of slow economic growth. Post-1948 India developed slowly, most obviously because of bad government policies that stifled growth in obvious ways. The recent removal of some of those policies has accelerated development. But colonial India also had slow growth, despite very good government policies. Taking the last two centuries as a whole, then, the Indian economy has been characterized by widespread poverty unparalleled in the world's industrialized countries. What is the role of entrepreneurial payoffs?

Discussions of the limited nature of India's economic development frequently attribute a major role to the difficulty of obtaining funding for the creation of new enterprises, or for the expansion of established firms. Yet, as is demonstrated in this chapter, India has possessed a profusion of well-functioning financial institutions, both before it achieved independence and since then. Indeed, there is a striking similarity between the structure and functioning of these financial institutions in India and those that were prevalent in the United States in the middle of the nineteenth century. Since that situation evidently did not prevent economic growth in the United States, inaccessibility to capital in India must be ruled out as an impassible obstacle to entrepreneurship and growth in India.

There was one important difference in the U.S. and the Indian systems. The provision of financial capital in India remained largely “informal.” Most financial capitalists chose to operate as private entities even though Indian financial entrepreneurs operated under a British colonial legal system that permitted incorporation and limited liability, and there were incorporated banks in India as well as stock and security markets. I argue that this propensity for informality may have been a consequence of the caste system. In the nineteenth century Max Weber famously argued that the Hindu social system failed to reward entrepreneurism and it was this misaligned payoff structure that stifled capitalist growth (Weber 1958). He noted that the Hindu caste system was tied to an acceptance of an immutable world order, and this, coupled with an expectation of reincarnation, led to disinterest in the mundane. While much of Indian business scholarship has been devoted to correcting the view that Indians were unconcerned with material gain, scholars have been forced to acknowledge that Indian business networks are affected by the caste system. In 1955 Helen B. Lamb observed that the vast majority of Indian entrepreneurs were drawn from just three communities: the Marwaris of Rajasthan, the Vanias of Gujarat, and the Parsis.1 This pattern continues even today, with every study showing that these same three communities control the lion's share of India's industries. The only change is that three other communities, Punjabi Khatris, Chettiars, and Maharashtrians have been added to the list as lesser, but still important groups (Khanna and Palepu 2004, 14).

The prevalence of these groups strongly suggests that the payoffs to entrepreneurism differed somehow across caste lines. The historical record suggests that wealth was not viewed negatively by any caste.2 The payoff structure of the caste system, however, gave members of moneylending and trading castes a good way to enforce contracts through reputation, and so made legal enforcement less necessary among these caste members. Caste membership itself deterred cheating. I will argue that India's formal financial sector remained undeveloped because the informal sector worked so well, at least within these groups. On the other hand, it is possible that by retarding the growth of less personal credit systems, India's informal systems may have lessened the payoff to entrepreneurism for nonmembers of these groups.

My chapter proceeds as follows. Briefly, I describe the sense in which colonial India's economic policies were good, but its economic development was not. I then describe colonial India's financial markets. I define the sense in which India's markets were more informal than those of the antebellum United States. Next, I examine data to measure the performance of the Indian system relative to the U.S. system. In the fourth section I argue that this informality may be linked to the caste system. I then discuss how the caste-based financial system that supported India's commerce and trade evolved into a caste-based managerial agency system that supported India's industries. The chapter concludes by speculating on potential connections between India's personal system of finance and its limited development.

The Institutional Environment and Economic Development of Colonial India

A major new research program—exemplified by the work of Stanley Engerman and Kenneth Sokoloff, and Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson—suggests that a key institutional characteristic is “the breadth of access to opportunities for social and economic advancement—the ability to own land, obtain schooling, borrow, and innovate.” What is crucial, in this view, is that laws and government policies promote broad participation in entrepreneurism. It is claimed that such a breadth explains the odd fact that the United States and Canada surged ahead of other American countries that were more resource rich (Hoff 2003, 207 and 208, respectively). It may seem surprising, but many of the U.S. and Canadian characteristics cited as growth enhancing reasonably describe the colonial Indian economy.

When Indians took over the governance of India in 1947, the main policymakers were determined not to repeat what they perceived to be the mistakes of the British. T. N. Srinivasan and Suresh D. Tendulkar write that the Nationalists thought that the British policies of laissez-faire and free trade were the major reasons for India's lagging industrial growth. They quote Nehru as describing world trade as a “whirlpool of economic imperialism.” The Nationalists replaced the British policies with what came to be known as the “License Raj.” This system required entrepreneurs to obtain a permit for any large industrial investment. Though it was originally put in place in an attempt to control and direct the economy for the public good, this system “degenerated into a tool for political and other patronage dispensation” (Srinivasan and Tendulkar 2003, 13 and 14, respectively). Moreover, licensing limited capacity and restricted supply. Firms could sell anything they could produce to domestic consumers, and thus had little incentive to improve quality or lower price. Labor management policies were also strictly circumscribed by government dictums. Independence meant that the mass of Indians gained the right to vote, a right that has been associated with good economic policies in many countries, says the new research agenda. For whatever reasons, however, the Indian electorate supported economic policies that clearly stifled entrepreneurism and innovation.

Compare this with the colonial regime. Though in terms of absolute numbers there were many educated Indians, the majority of Indians were illiterate, and that was almost certainly not good for growth. In addition, native Indians were largely excluded from government. Enfranchisement was limited, and the politicians who were elected primarily had advisory roles (Chaudhary 2006b). On the other hand, the policies that Britain imposed upon its colony most economists would describe as growth enhancing, such as the laissez-faire and free trade decried by the Nationalists. Sir George Rankin, a former chief justice of Bengal, described the legal structure of colonial India, in particular the law of contracts, as an improved version of British civil laws. The Indian Contract Act of 1872 was a simplified and codified version of existing British practices. When the British codified their own laws by the statutes of 1890 and 1893, “Sir Frederick Pollock had before him the [Indian] Commission's draft of 1866” (Rankin 1946, 93ff. and 97, respectively). The Indian law was modified in turn by the Indian Act of 1932 to bring it more exactly in line with British statutes, but, once again, Rankin argues, certain components of the Indian Act, in particular how it treated firms, were an improvement in clarity and completeness over existing British laws. Another point in favor of growth was that Indians were, largely, landowners. There were certainly many large estates and plantations in India, but the vast majority of Indian agriculturalists owned at least some land.

Thus Indians were given good policies and good laws, and through their landownership should have had access to credit. The large literate population, at least, should have been poised to innovate. Still, was their subordinate status in their own country an impediment to growth? Some authors, such as Subramanian Swamy (1979) and Amiya Bagchi (1972), have claimed the British government “placed hurdles” in front of native Indian entrepreneurs. But these authors' complaints are not that the British placed actual hurdles, but rather that the British failed to help entrepreneurs with subsidies and protective tariffs. More modern scholars—and certainly those concerned with productive paths of institutional development—would probably argue that the British failure in this regard during their tenure as rulers of India was actually the best help that could have been given to Indian entrepreneurs.

And in absolute terms, there was a great industrial expansion in India in the early twentieth century. Rajat Ray has shown that by 1939–40 the paid-up capital of jointstock companies registered in India had increased fourfold from its 1914 level. It increased an additional 50 percent beyond the 1939–40 level by 1946. The annual rate of increase between 1914 and 1946 was 16.85 percent (Ray 1979, table 9, p. 39). The joint-stock companies included industrial firms, but also were involved in banking, transport, plantations, mines, and estates. Bagchi notes, however, that as India had no indigenous machinery manufacturers, imports of machinery give an accurate index of physical investment specifically in industry. Denominated in 1929–30 rupees, the accumulated total gross physical capital imported into India across the first four decades of the twentieth century was nearly 4 billion rupees (Bagchi 1972, table 3.2). In this absolute sense, then, there was certainly impressive industrial investment.

Still the industrial sector remained small relative to India's overall economy. Net investment in the colonial period constituted only 2 to 4 percent of national income, as opposed to an average of around 23 percent of Indian GDP in recent years. Machinery investment in the colonial period was especially low in relative terms, only 0.5 percent of national income.3 Even by independence in 1947, despite the wartime surge in company registrations, the manufacturing sector represented just 16 percent of India's net product, and the largest part of that, 8.9 percent, was small-scale manufacturing (Heston 1982, table 4.3B). Between 1911 and 1951, the share of India's workforce in manufacturing actually dropped, from 10.1 to 8.7 percent. It should be noted, however, this was primarily due to a fall in female laborers in manufacturing. The percentage of male laborers in manufacturing was relatively stable: 9.5 percent in 1901 and 9.1 percent in 1951 (Krishnamurty 1982, table 6.2).

What is perhaps more important, productivity growth was minimal. Heston gives figures for the change in value added between 1900 and 1947 in all of the major sectors of the Indian economy (1982, table 4.4). Heston estimates that agriculture, which constituted about 70 percent of employment and GDP, may have even had a slightly negative annual growth in real value added per worker in this period. Manufacturing and commerce growth in real value added per worker was only about 1 percent. From this perspective, India hardly represented a dynamic economy.

Tirthankar Roy argues that India's resource endowments explain both the low investment levels and resulting lack of productivity growth. According to Roy, the scarcity and resulting high cost of capital and skilled labor in India meant that Indian industry was best suited to be, and was, “a vast world of traditional manufacturing, consisting of tool-based industrial production performed in homes or small workshops” (2002, 118). His argument echoes that of Morris Morris. Morris points out that though the official figures suggest that small-scale industry was both a bit larger and a bit more dynamic in terms of productivity than large-scale industry, because of serious underreporting in workshop activities in the interwar period, it may even have been more dynamic than the official figures would suggest. Further, the fact that Indian entrepreneurs were focusing on such workshops was not an indication of backwardness:

The introduction of modern (if often technically “outmoded”) machinery into a workshop context was the rational and quite efficient response by private entrepreneurs to cost and demand conditions as they existed over wide parts of the Indian economy. (1992, 221)

According to Roy and Morris, India was developing. It was just that India's development path was a bit different from that of Western economies, and that difference was due to the much greater cost of establishing modern industrial plants in India.

Morris adds another reason for Indian entrepreneurs' avoidance of large-scale industry, and that is their much greater familiarity with commerce and workshops. Morris's most recent statement on the development of industry in India was a 1987 article, but he has long claimed that the uncertainties of large-scale manufacturing were too great given the lack of infrastructure in India. Although Morris never cites Frank Knight directly, Morris is obviously referring to Knightian uncertainty, the distinction between “risk” (randomness with knowable probabilities) and “uncertainty” (randomness with unknowable probabilities) (Knight 1921). Morris points out that developed countries have “futures markets, statistical and other forms of specialized services that reduce risks and minimize uncertainties” (1992, 202). Indian entrepreneurs had, according to Morris, no such services.

Thus, a new enterprise had to promise a very high rate of return not only to meet the cost of scarce capital but also to allow for the greater risks. The higher the rate of return required to offset the general uncertainties of novel enterprises, the fewer were the opportunities that promoters and investors found promising. (1982, 557)

Morris's statement, however, highlights the need for financial entrepreneurs in India. The main purpose of well-functioning financial markets is to minimize risk to individual savers so as to facilitate the use of capital. There is greatest need for them when the payoffs to investments are most uncertain. Consider, for example, the theoretical model of Jeremy Greenwood and Boyan Jovanovic (1990). The job of the bank in this model is to accumulate costly knowledge on the uncertain aggregate state of technology. As banks are relatively large players, they have more incentive to pay the research costs than individuals, and they can offset risks among individual projects. For both reasons, in an economy with well-functioning credit markets there is more saving and more growth.

This line of argument suggests that colonial India would not have been a congenial environment for innovative entrepreneurs if there were insufficient financial entrepreneurs to take on the task of researching the unknown, or if for some reason financial entrepreneurs performed their task inefficiently. On one point Morris is obviously misjudging the sophistication of the Indian economy. Futures markets for cotton had been widespread in northern India since at least the very early nineteenth century (Bayly 1992, 395). By the end of the century there were deep futures markets for all agricultural products in all parts of India, which appear to have been the exclusive domain of native merchants (Ray 1988). But what of other forms of “intelligence gathering”?

Financial Markets of Colonial India

When the Europeans arrived in India in the sixteenth century, they found a sophisticated financial market already in place. Few writers describing this market fail to quote the following colorful observation by the great seventeenth-century traveler Tavernier.

The Jews engaged in money matters in the Turkish Empire are usually considered to be exceptionally able, but they are scarcely fit to be apprenticed to the money changers of India. (Tripathi 2004, 21)

The Indians had developed a system to transmit large sums across the great distances of India and even further. It was called the hundi system. A hundis was “a sort of bill of exchange drawn by a party on his agent or correspondent elsewhere, asking the latter to pay to the drawee a specified sum of money the equivalent of which the drawer must have already received” (Tripathi 2004, 18). By 1700 this system covered all of India and a market for salable hundis was developing. The network stretched from Surat to Dacca, and in the other direction over the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea to Makha” (Ray 1988, 265). Both the shroffs, or professional private bankers, and merchants were involved in selling and accepting hundis. It is thought that this system may have originated with the need of the many regional rulers of India to pay their troops.4 This network continued to operate under the British. The 1931 Central Banking Enquiry Committee estimated that 90 percent of India's inland trade was financed by indigenous bankers (Chandavarkar 1982, 798).

Official descriptions of India's informal credit network break the system into three levels: village moneylenders, town moneylenders, and, at the apex, private bankers. Bankers are typically distinguished from moneylenders in that the former accept deposits and the latter do not. However, this is not a hard-and-fast rule, and can be broken on either side.5 The most prominent caste groups of bankers include the Marwaris, who were originally from the northwest regions, but spread to all parts of India, and were especially prominent in eastern India; the Chettiars of Madras, who were also the main financial agents in Burma; the Khatris and Arora bankers of the Punjab; and finally the Bohras of Gujarat and the Multanis of Sind. (Note that with the exception of the Parsis and Maharashtrians, these are exactly the communities that have continued to dominate Indian entrepreneurism.) Timberg writes that the seminal treatment of the indigenous banking system of India remains L. C. Jain's 1929 book, an outgrowth of his Ph.D. thesis at the London School of Economics. Jain, a Marwari himself, gives the following description of indigenous bankers' activities.

Their offices and branches are spread all over the country in important centres like Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi, Rangoon, etc., where they have their munims and gumashtas or agents, who look after their business. The munims are invested with very wide powers. They are not highly paid, but their industry, integrity, and efficiency are remarkable and proverbial. They submit periodical returns and reports of their doings to their head offices and receive from them occasional instructions. Some of the bankers even have correspondents outside India, at Aden, Djibuti in Africa, Addis Ababa in Abyssinia, Paris, in Japan and other places. (1929, 36)

Even among the bankers, there were divisions between the large and the small. In a discussion of the Marwari diaspora, Tripathi notes that the migrants from Rajasthan were as a rule the small operators. The big bankers, who enjoyed the patronage of the Rajput chiefs, stayed in place, and their family members set up branches in other centers (Tripathi 2004, 86). Timberg likens this latter group to the Rothschilds studied by David Landes or the New England merchant migrants studied by Bernard Bailyn who founded their businesses on lines of credit from their “London creditor-relatives” (Timberg 1978, 102). The small operators were those who perhaps started as clerks to a larger house, accumulated capital, and then set up in business for themselves.

The indigenous bankers of India performed many of the same functions a formally incorporated bank would perform. They bought and sold hundis. (It is perhaps indicative of the dominance of indigenous bankers that in India all bills of exchange were referred to as hundis, even those sold by joint-stock banks and the Imperial Bank, the latter being the quasi-government bank of India.) Indigenous bankers offered lines of credit to their customers. Much of this business was done on personal account. They usually took deposits. Consider the example of Motiram Narasidas of Surat, interviewed by the Bombay Provincial Bank Enquiry Committee 1929–30. He was a pure banker in that banking was his only business. He received deposits, for which he paid 4½ percent. (The joint-stock banks were paying, according to Mr. Narasidas, 5 percent at this time.) He loaned only against personal security. His rate to other shroffs was also 4½ percent, going to 5½ percent at times, to merchants at 9 percent, and to agriculturists at 6–9 percent. Narasidas, though a private individual, reported that he issued annual balance sheets (Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee [Bombay] 1930, 1:152–57). The indigenous bankers were unlike more formal banks in that they typically operated chiefly from their own capital, even if they took deposits. Further, they rarely issued checks, and when they did, those checks were not accepted by formal banks, that is, the joint-stock banks and the Imperial Bank (Jain 1929, 43). These characteristics, however, were not unlike the private U.S. bankers studied by Richard Sylla, or even the early New England banks studied by Naomi Lamoreaux. She noted that for these banks, both banknotes and deposits held a “relatively insignificant position” among banks' liabilities. The bulk of their liabilities, as in Indian indigenous banks, was the bank's own capital (Lamoreaux 1994, 3; Sylla 1976).

Another difference between indigenous banks and formally incorporated banks was that indigenous bankers typically also carried on other business. Narasidas, referred to earlier, is somewhat unusual in that he was a “pure” banker. Jain writes that most indigenous bankers were simultaneously engaged in another “allied business,” and these included virtually every line of industry, trade and commerce. “They are grain dealers, general merchants, commercial agents, brokers, goldsmiths, jewelers, land-owners, industrialists and traders” (Jain 1929, 43). Ray notes that the two largest family owners of cotton textile mills in the Gujarat center of Ahmedabad, the Sarabhais and Kasturbai Lalbhai, continued with their indigenous banking business despite adding industrial pursuits to their portfolios. And the very wealthy Birla Brothers, who were jute mill owners, among other industrial activities, engaged in trade and most especially spot and forward transactions in the bazaar in the 1930s that were at least as large as their industrial interests (Ray 1992, 59). In both of these latter two cases, the financing available from their close connections to the indigenous banking sectors were instrumental in financing their industrial activities. I will return to the link between indigenous banks and Indian industrial financing in a later section, but here I want to note the similarities of this Indian system with the banks of New England described by Lamoreaux (1994). She argued that buying commercial bank stock in antebellum New England amounted to joining an “investment club” in which members' savings were sent to the enterprises of the directors of the bank.

Each Indian firm acted independently, according to Jain. They did, however, have guilds, sometimes called mahajans. These institutions were part caste panchayat, or council, and dealt with religious and social matters, and part trade dispute and insolvency courts.6 In some parts of India, the mahajans evolved in the interwar period into “associations,” but performed exactly the same role that the medieval Indian guilds had performed. Jain notes that the Bombay Shroffs' Association settled between twenty and twenty-five disputes a day. They had a form in which all of the details of the case were noted, including the parties to the dispute. The secretary of the association investigated, and handed down a decision. Jain writes that these decisions were accepted by all. On the few occasions when the parties took the dispute to a formal court, the decision of the association was typically upheld, as it had been arrived at from “personal knowledge.” In Gujarat, also in western India, the association set the hundi rate, by which all members abided. The setting of intra-shroff rates was apparently also the practice of the Bombay Association.7

The Nakarattar Chettiars had the most formalized overarching organization of all of the communities of indigenous bankers (Rudner 1994). The Nakarattar Chettiars were and are a caste based in Chettinad in Madras. They were the main financiers of this region, but were even more famous for their widespread operations in Burma, Ceylon, and Malay. At least before the 1930s, the bulk of their collective funds was employed outside of India. The Nakarattar Chettiars held monthly meetings to discuss the current financial situation and set interest rates, as did other groups. The Chettiars, unlike other banking groups, were a single caste rather than a caste group, and the meetings were held at their temple. The caste panchayats of the Chettiars were used to settle disputes between Nakarattar businessmen over payment of interest on loans, return of deposits, or other business matters. The Chettiars were unlike other banking groups in another way. There were two formal layers of bankers. A small number of Chettiars, Rudner estimates something like 10 percent, were designated as adathis, or parent bankers (1994, 128ff.). They acted as clearinghouses between individual Nakarattar Chettiar bankers, much as a large New York or Philadelphia bank might have served as a correspondent bank for small rural banks in the antebellum United States. Two bankers did not have to know one another if they had a common adathi. Further, excess funds could be deposited with an adathi who would have the most up-to-date and complete commercial knowledge.

These organizations of bankers would in many ways have mitigated the uncertainty of business operations in India. Colonial Indian businesses were not operating completely without commercial information. The British administration in India had produced unusually good information for a poor country on agricultural prices and population since the 1870s. In the 1920s, labor bureaus were started in the various administrative centers and researched and published all information that was considered relevant to the labor markets (Mehrban 1945). Still, it is likely that there was a lack of formal private or government-sponsored commercial intelligence relative to more developed contemporaneous countries. And because India remained till well past independence dominated by small workshops and farmers who were only partly producing for the market, the economy was almost certainly less knowable than those same developed contemporaneous countries. The organizations of bankers, however, had contacts in every part of India, and in the case of the Chettiars, in many other parts of Asia as well. Their meetings were opportunities not just for setting interest rates and settling disputes, but also for exchanging information. Rudner claims that caste gatherings at weddings and funerals were just as important for learning of new business opportunities as they were for cementing social ties. The organizations themselves would not have conducted the “research” Greenwood and Jovanovic envisioned for commercial banks, but it seems unlikely that any good industrial opportunity that presented itself to any individual indigenous banker would lack for funds, even if he alone could not supply the investment capital. Individual indigenous bankers were independent, but not isolated.

The informal nature of India's financial system did not harm its ability to support agricultural production and commerce. In an important article, Ray gives a thorough discussion of the workings of the “bazaar” credit system for financing India's agricultural trade in the interwar period. He cites one example pulled from the records of the Bihar and Orissa Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee of 1929–30 that is a particularly nice description of how the system worked. The Province of Bihar and Orissa was just west of the Province of Bengal. Coconuts were one of the main crops of the Puri district, and were sold to confectioners, chiefly in the nearby Central Provinces (CP).

Four coconut dealers at the railhead, one Marwari and three Oriyas, bought up the coconuts from local Brahman agriculturists who collected the produce of other ryots and moved the nuts by road to the railhead. The four coconut dealers financed one quarter of the nuts by advances which carried no stipulation of exclusive right of purchase and they paid cash down for the other three-quarters. When the mandi [market town] merchant at the railhead filled an order from a CP confectioner by railing the ordered coconuts, he telegraphed the buyer, who wired back that he should draw a hundi on a particular merchant in Bombay or Calcutta. The coconut merchant drew a hundi accordingly and sold it locally in Puri to a merchant willing to remit money to either Calcutta or Bombay. He usually got a premium for a hundi drawn on Calcutta, to which plenty of merchants wished to remit. By contrast, he had to sell hundis at a discount in Bombay where fewer merchants wanted to remit money. (Ray 1988, 288)

Thus the mandi merchants were first engaged in financing the coconut growers, and then participated in the financing of the final sales through the hundi market. Ray argues that the system, while “unorganized” by Western standards, was perfectly suited to the “monsoon economy and rural production organisation of India.” According to Ray, the greater riskiness of agriculture in India meant that it was necessary to spread out the risk over many different agents.

This system was, in fact, not unorganized or particular to India. It seems very similar to the way cotton production, for example, was financed in the nineteenth-century United States. Harold Woodman describes a two-tier system (1968, esp. 76–83). For large planters in the antebellum period, there were agents who supplied credit beforehand, and sold the cotton after the harvest. Like the Marwaris and Oriyas of India, they had no legal right to market the crops, but often did. These were called factors. Smaller planters appear to have dealt more with the local storeowners, who supplied credit, and then sold the crops. These store owners themselves typically received credit from a factor. It is true that Indian farmers did not rely on commercial banks for agricultural credit, but then neither did farmers in the antebellum or postbellum U.S. South.

The mainstay of Indian rural credit were the rural moneylenders—the bottom rung of India's credit ladder. These were an extremely diverse group. Jain writes, “So far as money-lending is concerned, any one and every one takes to it. A member of any caste who may have a little money in hand can hardly resist the temptation of lending it out to neighbours” (1929, 28). This is a common theme in official documents. Peter J. Musgrave quoted an early1860s statement of the deputy commissioner of Rae Bereli, which is in the United Provinces, north India, on this point: “Almost every man appears to be in debt, and he who saves a rupee puts it out upon interest” (1978, 219).

Efficiency of Colonial India's Financial Markets

To provide financial capital efficiently for both industry and agriculture, the Indian system would have to have been integrated across its layers and across geographic distances. There was the appearance of different spheres and, thus, a separation between the formal and the informal sector. Still, there were channels for funds to flow across functional spheres.

The Imperial Bank, exchange banks, and joint-stock banks were at one extreme. They handled the export trade. There are also indications that they handled the less risky parts of Indian business. Consider the evidence of Rai Surana before the Bihar and Orissa Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee on October 26, 1929. Surana was the manager of the Bhagalpur branch of the Benares Bank. The Benares Bank was founded in 1901, and this branch was founded in 1909. This branch collected about one-third of the bank's total deposits. Surana reported that the main business of the bank was to lend money against pronotes (promissory notes) and hundis and give cash credits and overdrafts. It also sold government securities. When there were no good prospects locally, the branch put idle funds at deposit at the Imperial Bank in Calcutta. The bank financed neither agriculture nor industry, but it did lend to traders and to zamindars, the landlords of large estates in British India. In particular, the branch did not fund the local tannery. Surana noted, “The tannery in Bhagalpur was refused accommodation even by the Director of Industries because tanneries are not regarded as sound business” (Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee [Bihar and Orissa] 1930, 3:160–64).

The indigenous bankers operated in a somewhat different sphere than the formal banks. Like the Benares Bank, many indigenous bankers held deposits at the Imperial Bank. They periodically received accommodation from that bank and other formal banks. They were different in that they had a wider circle of personal knowledge, and were willing to have borrowers deemed too risky by the formal banks. Baker in his study of Madras found that the Imperial Bank had a list of “approved” Chettiar bankers. Baker writes that these bankers frequently borrowed from the Imperial Bank, tacked on 0.5 percent, and lent to an “unapproved” banker who was known to the Chettiar banker (Baker 1984, 287). The other branches of the Imperial Bank had similar lists of approved indigenous bankers in most provinces. The Central Banking Enquiry Committee reported that though indigenous bankers only indirectly loaned money to agriculturists, except in Burma, they “always maintained a close personal touch with the trader and the small industrialist” (Indian Central Banking Enquiry Committee 1931, 1:105 and 99, respectively). The tannery in Bhagalpur, spurned by Surana's Benares Bank as well as the colonial government, was probably financed by an indigenous banker. Indigenous bankers, however, were not unconnected to larger-scale industry. Tripathi notes that the bankers frequently purchased mill shares, and Jain notes that the indigenous bankers would leave large deposits with the large cotton mills of Indore in central India, though this largely constituted short-term lending (Tripathi 2004, 132; Jain 1929, 48).

Though the connections between the formal and indigenous banks to agriculture were indirect, funds from the commercial and indigenous banks were channeled to agriculture as well as industry. There were two ways. Sometimes the traders who had been loaned money themselves would subsequently lend money to the agriculturalists. Baker writes that the produce of Madras Province was sold to village dealers. Production and credit expanded “as more and more village dealers became known in the urban market and were able to borrow extra funds from the indigenous bankers” (1984, 258). The connection running between the Imperial Bank and the indigenous banker who lends to the local dealer is well summarized in the following quote from a witness before the Madras Provincial Bank Enquiry Committee.

Indigenous bankers can be said to be practically helping agriculture, trade and industry in the district [Tanjavur], say to the extent of 60%.…The indigenous bankers generally start with a very small capital. The Imperial Bank of India and joint-stock companies [banks] help them to a certain extent. They easily influence the public and get deposits which, in some cases, rise to several times the capital. There are instances where private bankers started business with a nominal capital of Rs. 10 or 20 thousands and transacted more than Rs. 15 lakhs [1.5 million rupees] within a period of fifteen years. Finally when the accounts were closed they had a surplus of Rs. 1, 2 or even 3 lakhs in some cases. (Baker 1984, 287)

Another channel through which the funds of the indigenous banker reached agriculture was that the bankers would lend money to smaller moneylenders (small relative to the banks), who loaned to agriculturists. Musgrave relates the story of a rich agriculturist in Chakerji, a village in Etah in the United Provinces. The agriculturist, named Narayan Singh, lent from his own profits. He found this so lucrative that he borrowed 2,000 rupees in 1885 from a Bohra banker in Kasganj, paying interest at 12 percent per year and lending out at 3.125 percent per month (Musgrave 1978, 218). The evidence of the indigenous bankers before the Bombay PBEC report suggests that this was common practice even in 1929. The rate at which moneylenders could borrow from the shroffs had not changed much from Musgrave's example (Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee (Bombay) 1930, 1:200, also 3:483).

Of course large agriculturists could borrow directly from the bankers, as in the case of the Gujarat banker Narasidas mentioned earlier. And all of these bankers and moneylenders might themselves be brokers or traders, or in fact even agriculturists. It was an extremely fluid system with no legal segregation, and the traditional occupational segregation among these productive activities was much more fluid than one might have supposed.

Ray argues that the integration was incomplete. While he acknowledges that “there was a large downward flow of credit,” he claims that the connection between formal banks, the bazaar, and the rural economy was weak.

The sphere of the bazaar is thus clear: it operated at the tier of the marketing hierarchy where hundis were in circulation. This excluded at one end the village shandies which had no sources of mobile credit, and at the other end the international ports-of-call which possessed the higher but entirely alien financial instruments of the exchange banks. (Ray 1988, 278)

The evidence Ray gives to support his claim is twofold. On the disconnect in the system between the formal banks and the bazaar, he argues that there is no connection between the hundi rates of the bazaar and the Imperial Bank call money rate. The second disconnect, what Ray terms the “cleavage within the indigenous system,” occurred because there were no “negotiable instruments” in use connecting the shroffs to the sowcars, or moneylenders. Funds moved between these two groups through the “clumsy use of book credits,” which were unable to ease the seasonal credit shortages in the country caused by the monsoon growing season. In many areas of India there are two cropping seasons. The monsoons come in the early summer months. The kharif, or rainy season crop, is put in the ground during the monsoons, and harvested in December. Then the rabi crop is sown, and grown on residual moisture from the monsoon. It is harvested before the monsoons come, and is typically the larger crop. Ray writes, “From May to August rural creditors needed funds to make advances to the cultivators for sowing the kharif. The funds lying idle in the bazaar could not find congenial employment in the mofussil precisely when there was stringency there” (1988, 277–78).

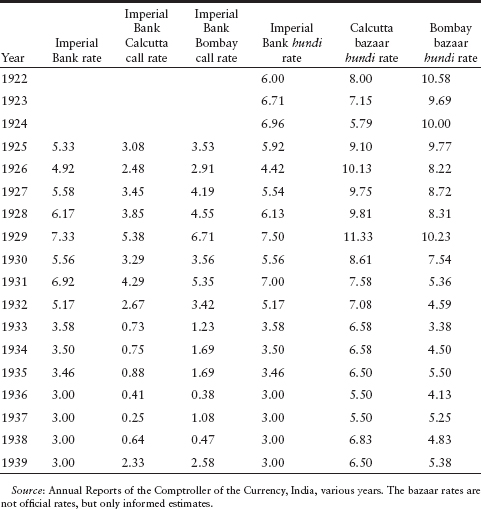

TABLE 15.1

Annual Bank and Bazaar Rates in India

Ray's claims are testable. Starting in 1922, the comptroller of the currency of India published monthly estimates of the bazaar hundi rate for Calcutta and Bombay, as well as the Imperial Bank bank rate, the Imperial Bank call money rates for Calcutta and Bombay, and the Imperial Bank hundi rate. Annual values for these are given in table 15.1. There is typically, though not always, a wedge between the rates of the Imperial Bank and the bazaar. But, as discussed above, the bazaar took on riskier clients. There are also differences between the Bombay and Calcutta rates.

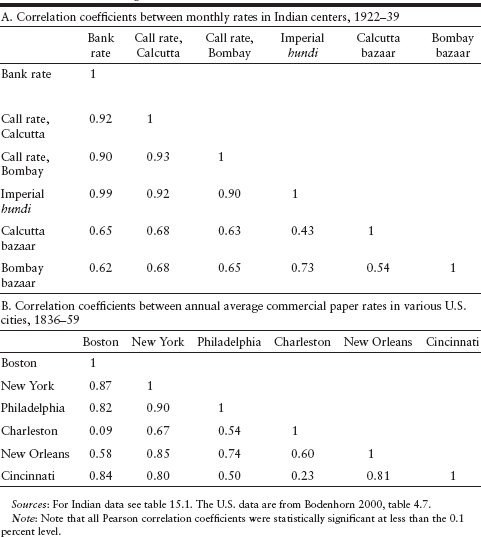

TABLE 15.2

A Comparison of the Integration of the Indian and U.S. Financial Capital Markets

We can formally test for integration using correlation coefficients. The results of this test are given in the top panel of table 15.2. All measures are statistically significant, suggesting that these were not separate markets. To interpret these numbers, we need to put them in perspective. Howard Bodenhorn reports the interest rates on commercial paper in various U.S. cities. Though he does not use them for this purpose, I have constructed correlations, which are reported in the lower panel of table 15.2. The northeast centers of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia are more integrated than Indian centers. On the other hand, cities such as Charleston, and even New Orleans, are not more tightly linked to each other or to the major financial cities than were Bombay and Calcutta.8

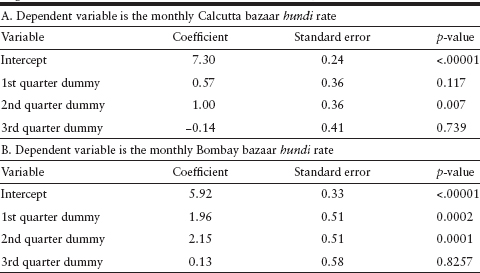

The reported bazaar rates also let us examine the issue of seasonality. Ray argued that his reading of the official documents suggests that after the rabi harvest, from May to August the bazaar funds were idle when they could have been used by the rural sector to advance monies for the kharif, or rainy season crop. Table 15.3 reports the results of regressions testing for the degree of seasonality in the Bombay and Calcutta bazaar rate data. The data do suggest strong seasonality in the bazaar rates. Rates appear to rise between one and two percentage points in the first six months of the year. The seasonality is greater in the Bombay bazaar.

Once again, we should put these numbers in perspective. The United States, in fact all gold standard countries, experienced seasonality of money demand in the nineteenth century, with rates peaking just after the harvest in September and rising through January, though it is also true that in the United States, this seasonality lessened considerably after the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1914. Truman Clark reports estimates of the degree of seasonal rate differentials in the United States for various measures including the call money rate, 60–90-day commercial paper, and the 90-day time money rate. Between the years 1890 and 1913, the peak differences between these rates was between December, the peak, and January, the trough. The average differences are 2.28 percent for call money, 0.50 percent for commercial paper, and 0.88 percent for time money (Clark 1986, table 2). While these rate differentials, except for call money, are a bit lower than the seasonal differentials seen in India, they are of the same order of magnitude. Thus, if India suffered from a seasonal change in money demand, it suffered no more than had the United States in the nineteenth century. Further, because the drop in rates postharvest is similar to what was experienced in the United States, it seems unlikely that the Indian rural-urban financial market integration was any less than the U.S. rural-urban integration.

TABLE 15.3

Regressions of the Seasonal Pattern of Bazaar Rates in India, 1922–39

Caste and Colonial Indian Credit Markets

The analysis thus far has shown the similarities between the Indian credit system and the mid-nineteenth-century U.S. financial system. But there were significant differences, including the extent to which informal credit exceeded formal credit, and the widespread involvement of many individuals in rural lending. The cultural institution of caste played an important role in the Indian credit system and may partly explain these two oddities of the Indian credit system. Though caste has many aspects, most economists have focused on just two: the hereditary assignment of some occupations such as priests and manure collectors or sweepers, and the hierarchy that separated, socially and economically, the high castes from the lower castes. However important these may be for both the speed and the morality of Indian economic development, they are not my focus. I want to concentrate on a different aspect of caste. Whatever else it was, caste is an extended, somewhat formalized kinship network. M. N. Srinivas argues that despite the scorn heaped upon it, few Indians would want to abandon the caste system, as “joint family and caste provide for an individual in our society some of the benefits which a welfare state provides for him in the industrially advanced countries of the West.”9 Continued membership in the network required meeting certain obligations. If a member failed to meet his obligations, he, and his family, would be formally outcasted, and lose all benefits of membership. In India, there were accepted, formal means of adjudicating cases in which members failed in their obligations to the social network. Each caste had its own panchayat, or council, over which the headman of the caste officiated. Cases taken up by the caste panchayat dealt with personal matters that would lower the reputation of the caste, such as irregular unions and family quarrels; with land disputes; and with other disputes between caste members. The panchayat had other functions such as planning community festivals, or reforming the subcaste, or jati, customs (Kolenda 1978, 89). The decisions of the panchayats are upheld by the group. The punishment meted out for grievous violations of caste rules is to “deprive a casteman of the right to receive water, or the tobacco pipe, from the hands of his fellow castemen and forbids them likewise to receive it from them.” This effectively expels him from the community. He will not receive help in time of difficulty. There will be no one for his children to marry. Kolenda writes that the resulting “social control of members is unusually strong and effective” (1978, 11).

Credit contracts are by definition an exercise in trust. The larger the funds involved, the longer the time period between borrowing and repayment, and the more geographically distant the parties, the greater must be the trust to induce both parties to enter the contract. Lamoreaux believes that the fact that businessmen and bankers were related by blood or marriage in early nineteenth-century New England facilitated the development of credit networks. Those who either defaulted on loans, or used funds improperly, “risk[ed] ostracism from the kinship group and the loss of both their claims on family resources and the connections vital to business success” (Lamoreaux 1994, 26).

Caste extends the kinship network to include more individuals and increase its benefit, and simultaneously raises the cost of transgressing the social norms by formal outcasting. Both Rudner (for the Chettiars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries) and Bayly (for north Indian merchants of the seventeenth) argue that if a businessman acted unscrupulously, not only would he lose business connections, his children would become unmarriageable (Rudner 1994, 128; Bayly 1992, 375). More formally, Bendor and Swistak determined that in an evolutionary game theory framework, some degree of cooperation may be sustained in the absence of binding institutional supports if there is a sufficiently dense social network so that everyone knows who has cooperated and who has not, if there are sufficiently severe penalties for cheating, and if punishment is multilateral; a failure to cooperate with any one individual must lead to retaliation by the entire group. The level of cooperation chosen will depend upon what players expect other players to do, and the levels of punishment (Bendor and Swistak 2001). As the caste system provided all of these criteria—communication, multilateral punishment, and harsh penalties for defection, theoretically it should have been capable of sustaining a much higher degree of cooperation than a less extensive, less formal network. On a more empirical basis, Timberg writes, “It may be that many institutions, such as the joint family and strong, particularistic caste loyalties are the secret of success in Indian business and industry.” In particular, he argued that it was the Marwaris' wide resource group that was the secret of their commercial and industrial success (Timberg 1978, 17 and 98, respectively). Other analysts were impressed with the integrity of Indian financial intermediaries. Cooke, describing Indian private banking in 1863, was impressed by a system in which, “although millions were invested, the loss of bad debts, arising out of the dishonour of the instruments at maturity, was a most insignificant fraction per cent” (Ray 1988, 305). Seventy years later the authors of the Bihar and Orissa PBEC wrote:

The word of the shroff is better than an expensive bond. None of the large mathudhar transactions—transactions which are carried on daily by shroffs amongst themselves by word of mouth without any written record or document—are ever denied. The slightest rumour of unfair dealing with clients will impair such sensitive credit.

It is not only the chief bankers who maintained a reputation for probity. The Bihar and Orissa reports give the following account of an establishment of indigenous bankers.

The employees of the [indigenous bankers] are generally poor relations and caste men imbued with the traditions and well acquainted with the practices of the profession. As such they are thoroughly amenable to the social influence of the caste panchayat, which is always more effective in securing honesty than any legal penalty. (Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee [Bihar and Orissa] 1930, 193 and 195, respectively)

I noted earlier that the decisions of the Bombay shroff association were considered binding and just by its members (Jain 1929). The Indian financial network may have remained informal because this informality had so little cost in India, given the private incentives for honesty.

This argument suggests a never fully explored role for the concentration of entrepreneurship among certain Indian castes. Kripa Freitas has speculated on the role of caste in sustaining contracts (Freitas 2006). Analysts describing the indigenous banking sector certainly suggest that caste ties were important deterrents to cheating. Such arguments suggest that certain castes were more likely to engage in entrepreneurism, not because of any cultural predisposition, but rather because, if the business network in part depended on caste connections, members of different castes when choosing a career had different ex ante relative profit expectations. This is not to say that business activities and support were restricted to intracaste ties, which the empirical record shows to be patently false, but rather that intracaste ties had an additional means of contract enforcement that seems likely to have affected relative payoffs.

The Indian Financial Market and Indian Industrial Organization

Peter Rousseau and Richard Sylla (2005) argue that the expansion of the formal banking system in the United States spurred the development of a liquid securities market, and that this in turn spurred incorporation. For the United States, they argue, the development of formal, liquid financial markets exploiting limited liability induced investment by both domestic and foreign investors.

A similar pattern did not occur in India, even though all of the legal apparatus was in place: there was a formal banking sector, a securities market, and incorporation. Instead, managing agencies evolved as a hybrid of family firms and incorporation. Caste networks of trust in India's financial systems could be responsible for the development of this uniquely Indian form of industrial finance. Many of the most important managing agency firms of the colonial period were offshoots of the family firms of indigenous bankers, such as those of C. N. Davar, who built the first Indian cotton mill, and J. N. Tata and G. D. Birla (Lamb 1955). But while indigenous bankers remained completely outside of the formal, regulated system, managing agencies adopted some aspects of the formal system. The Indian managing agency remains today a legally distinct firm that promotes, finances, and acts as the “decision-making unit” of one or more other “legally separate and presumably independent” firms (Brimmer 1955). Typically the operating unit was a joint-stock company. Sometimes the managing agency was publicly traded as well.

Though Lamb and Brimmer attribute the invention of the managing agency structure to English entrepreneurs in India, Tripathi claims that its structure is Indian: “For shorn of details, the managing agency structure represented an adaptation of the joint family system, still a prominent feature of the Indian social structure, for managing a business enterprise” (2004, 113). Partnerships, according to Tripathi, were too risky for “cautious Indian investors,” and the managing agency “was an organizational fiction” that allowed private control while utilizing the joint-stock system. If Morris is correct and unknowable uncertainty was the main deterrent to Indian industrialization, then the managing agency was a brilliant adaptation. It allowed the entrepreneur to manage and finance a firm while also protecting himself from full exposure to the risks of new enterprises. Brimmer found many managing agencies that controlled just one independent firm. He also found some individuals who controlled more than one independent firm, but did so using a distinct and separate managing agency for each firm. Though Brimmer did not believe he had a completely satisfactory explanation for this pattern, he thought it was linked to the wealthiness of individuals controlling the managing agency, and at least in 1951, to the fact that the bulk of that wealth had been generated through trading. The industrial concerns were relatively small parts of the overall operations of the individual's or family's business interests. By having a separate “firm” manage each company, only the assets invested in that firm were at risk. The managing agency would have all of the benefits of flexibility associated with vertical and horizontal industrial integration, while risks would remain compartmentalized by limited liability.

The Indian managing agency has not escaped criticism. Some detractors believed that it had not evolved sufficiently far from its family-firm origins. Lamb, for example, thought there were two tiers of managing agencies. Those who “rationalize their operations, publish adequate records, maintain plant, deal effectively with labor and delegate authority to professional staffs,” and those who maintain company secrecy, rely too heavily on family members and ‘fellow castemen,” and emphasize quick profits (Lamb 1955, 108). Brimmer is even more damning, arguing that English managing agencies overwhelmingly comprise the first group and Indian managing agencies the second. Brimmer especially faults the Indian managing agencies for secrecy and nepotism.

Small firms facing relatively large risks may have relied on a limited labor pool for the extra advantages that kinship connections brought, such as greater trustworthiness, but the ill effects of nepotism in managing agencies were moderated as the firms expanded. Lamb notes that as firms grew larger, they consistently reached out beyond caste and community boundaries so that the boards of the largest and most successful firms would have representatives of several mercantile communities (1955, 110). It is important to realize that this was not a modern phenomenon stemming from a movement away from traditional attitudes. Christopher Bayly studies the business communities of eighteenth-century north India. As mercantile interests became more politically secure, caste connections were supplemented with other types of connections. It was not that caste connections disappeared, but rather that they were bound into larger units. He argues that “caste and religion provided the building blocks out of which mercantile and urban solidarities were perceptibly emerging.” Bayly believes these multicaste groups were stronger because each part within the whole was held together by caste ties (1992, 177ff.).

The role of caste connections in corporate governance and finance has not faded away since independence despite the expansion and development of the Indian economy. Khanna and Palepu study the evolution of the structure of control of India's modern industries between 1939 and 1997. They have found that family-run business groups continue to dominate Indian industry. These family groups—such as that of the Tatas or the Birlas—are direct descendants of family-run managing agencies. At least in the early 1990s, while there were roughly as many non-group-affiliated private firms as family-group-affiliated private firms listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange, the group-affiliated firms' average sales were almost four times as large. The entrepreneurial families behind these groups tend to be drawn from the communities of the Marwaris, Parsis, Gujarati Banias, and Chettiars, as was true of the indigenous bankers and industrialists in the colonial period.

Khanna and Palepu claim that the personal nature of business practices in India has its uses. In developing countries some markets are missing, such as the market for venture capital and that for managerial talent. Family groups have superior knowledge of and access to financial capital and people. They can utilize these resources as substitutes for the nonexistent impersonal, arm's-length markets. Of course, there are obvious potential moral hazards when one group has superior access to resources, but such potential inefficiencies are less of a problem when there are many rich families, each with access superior to the bulk of the population, but not relative to one another. In their study Khanna and Palepu find there was more turnover among India's top fifty firms than among the top fifty U.S. firms over the same time period, and thus they conclude that though Indian markets are dominated by recognizable families, competition across these families is probably sufficient to punish inefficient nepotism and secrecy. Their arguments are similar to Lamoreaux's claim that in early-nineteenth-century New England, a small group of “insider” bankers with their superior knowledge of available opportunities could more efficiently finance investor projects than could an ill-informed market. She argues that though these insider bankers had superior access to resources, the outcome was efficient because entry to the banking sector was easy. Competition among the insiders provided the necessary discipline.

There is, however, one striking dissimilarity between the Indian case and New England. While personal finance of industry persists in India even today, insider lending disappeared in New England by the late nineteenth century (Lamoreaux 1994). It was replaced by professional bankers with no business interests to impair their “objectivity and impartiality.” Banks ceased to act as interested investors, and simply became collectors and dispersers of savings.

I think these very different trajectories may be the key to understanding how India's culture has affected the development of Indian industry over the twentieth century. While it seems reasonable to argue that competition among a fairly large set of entrepreneurs, even if it is a limited set, might lead to a socially efficient allocation of a fixed level of financial resources, it is still possible that the limits of the set might affect the accumulation of financial resources over time. Many years ago George Akerlof speculated that because each Indian managing agency can “be classified according to communal origin” or caste, the group could use communal social sanctions to encourage honesty. He also argued, however, that such a structure might lead to expropriation of the return of any investor in the managing agency who was not of the same caste community, and thus discourage saving. As evidence he pointed to the more heterogeneous mix of stockholders in British-owned managing agencies in India relative to Indian-owned managing agencies (Akerlof 1970). More recently, Mobius and Szeidl presented a model that highlights the trade-offs between the trust generated by tight networks, and the limits to the network maintaining trust requires. Their model was meant to examine the provision of informal credit in less developed countries “where legal contract enforcement is unavailable or costly” (Mobius and Szeidl, 2007, 1). The interesting insight for my purposes is that when the need for trust is greatest, such as diamond merchants in New York City, social welfare is highest in tightly connected societies, but in contrast, when the stakes are lower, such as borrowing for a bicycle or a car, social welfare is highest in more diverse communities. First let me note that legal contract enforcement is always costly, even in modern societies with formal financial institutions. One might then interpret impersonal commercial banks and finance through impersonal stock offerings as a “low trust” system and indigenous banks and family dominated managing agencies as a “high trust” system, that is, a system in which trust rather than legal enforcement plays a relatively important role. Commercial banks keep extensive public records, as do publicly traded companies. Indigenous banks are repeatedly described as secretive, as were traditionally oriented managing agencies. Secrecy requires greater trust, and thus caste ties were necessary to maintain honesty. Secrecy also undoubtedly has some advantages. Resources can flow with great flexibility and minimum transactions cost along such networks.10 But theory suggests that secrecy has a cost too: the limitation of the network of participants. Given that both systems have advantages, one cannot say absolutely which is better. The contrasting experience of widespread growth in the nineteenth-century United States and the limited scope of wealth accumulation in twentieth-century India, however, would at least a priori suggest the advantages of financial transparency and diffuse participation.

Restriction of Entrepreneurship?

My thesis would suggest that the chief Indian industrialists should all have had similar backgrounds. Consider as an initial sample the head of the nineteen Indian family groups Markovits identifies among the top fifty-seven Indian business groups in 1939. Markovits gives a thumbnail sketch of each of the main industrialists at the end of the colonial period (Markovits 1985). These sketches allow me to identify the caste affiliation of seventeen of the nineteen large business groups he identified. There are seven firms from the Bania caste of moneylenders and traders. Six of these are from Gujarat. There are four firms with Parsis connections, and four firms with Marwari connections. The firm of Thackersey is from a family of Cutchi Bhanias, a trading caste that originated in Sind, now Pakistan. Another firm was headed by Mafatlal Gagalbhai, a Patidar Kanbi from Gujarat, a Shudra. We can add to this list the Indian partners of Martin Burn, the second-largest business group in India in 1939. Markovits identifies this firm as English because the largest shareholders, with 40 percent, were the English Martin family. But there were two significant Indian partners: Mukerjee, who held 37 percent, and Banerjee, who held 17 percent (Herdeck and Piramal 1985, 210). Their share of Martin Burn places them in a category of business importance similar to the other Indians I have listed. Mukerjee and Banerjee were Bengali Brahmins.

Since this is a small list of entrepreneurs, perhaps we might also consider the thirteen whose biographies are highlighted in the book Indian Industrialists, by Gita Piramal, now a recognized expert on Indian business families, and her coauthor, Margaret Herdeck. This book identifies some of the giants of Indian industrialization from the late colonial and early independence period. The authors claim to have pulled these names almost at random from the major industrialists of the era, but most scholars would, I think, consider this a fairly representative list of important entrepreneurs. Several entrepreneurs highlighted in this work overlap those included in Markovits's list of the fifty-seven large business groups in 1939. These were Tata, Birla, and Mafatlal Gagalbhai. The others are Bajaj, Goenka, Modi, Ambani, Oberoi, Thapar, K. C. and J. C. Mahindra, Kirloskar, and T. T. Krishnamachari. The first two were Marwaris; Modi was an Agarwal from Uttar Pradesh, a related caste. Ambani is a Gujarati Bania. Thapor, Oberoi, and the Mahindra brothers were all Punjabi Khatris, another moneylending, trading caste. Kirloskar and T. T. Krishnamachari were both Brahmins.

Thus all but one of these entrepreneurs were either from moneylending, trading castes or Brahmins. Only one, Mafatlal Gagalbhai, was of a lower caste. (Shudras are the lowest of the four varnas, but they are above the so-called untouchables.) Gagalbhai's father was an artisan, and he himself began life peddling his own handwoven gold lace, carrying his wares in a sack on his back. Mafatlal proves that it was not impossible for an artisan to rise to wealth without family connections, but he is the only example of a nontrading caste, non-Brahmin entrepreneur.11 To appreciate how limited the network appears to have been, note that in the census of British India in 1931, only seven million, or slightly less than 2 percent of Indians, identified themselves as belonging to traditional merchants and traders castes, a group that included Baniya, Bhatia, Chetti, Khatri, Komati, and Vaishya.12 Brahmins constituted a further 15 million, or 4.3 percent of the population. In a 1997 article in the Indian magazine Business Today, Gita Piramal argued against the notion that Marwaris alone dominated Indian industry. She wrote: “A closer look allows us to throw out this hoary notion. There are more Sindhis, Parsis, Punjabis, Chettiars and Brahmins than ever before in the Top Fifty [Indian business groups]. If there is a trend, it points to a more broad-basing of entrepreneurship in Indian than ever before” (Piramal 1997, 22). Since even this wider group is still just a small share of India's overall population, I would respectfully suggest that the description “broad-basing” in this case is quite relative.

Of course, I am not arguing that one had to be from a trading caste or a Brahmin to be an entrepreneur in India in the colonial period or today. I have already mentioned Mafatlal Gagalbhai. Also, there were at least a few Muslim textile mill owners in colonial Bombay. But the preponderance of trading caste members and Brahmins, especially the former, among important entrepreneurs, given their quite small share of the Indian population as a whole, is certainly suggestive that there was some factor that afforded these individuals superior access to opportunity.

I will add one more fact that I think is relevant to the question of whether trading caste members themselves believed they faced different ex ante opportunities. Primary education was in large part privately funded in colonial India (Chaudhary 2006a). Thus, if an individual was literate, it was at least in part driven by his parents' demand based upon an assessment of his expected return. The 1931 census gives rates of literacy for some select castes. Among the general Indian population five years and older, only 15.6 percent of males were literate. Among Brahmins five years and older, 23 percent of males were literate. But among the Baniya, 54.4 percent of males were literate. Among the Chetti, 44.7 percent of males were literate. And among the Khatri, 45 percent of males were literate.13 There was something clearly different about India's trading castes.

Conclusion

Was India's unusual credit system a hindrance to economic growth in the colonial period? If it were, it was not due to obvious problems such as an absolute scarcity of capital or a lack of sophistication. And if Indians were lacking for resources, Indians as they began their industrialization path were no more constrained for financial capital than U.S. entrepreneurs had been as that country was industrializing in the mid-nineteenth century. But Indian credit, unlike the U.S. financial system, was largely provided informally. I have argued that caste appears to have provided an enforcement mechanism alternative to formal laws. Caste connections among financial firms thus decreased the costs of remaining outside the formal sector, and allowed Indians the relative freedom of continuing as private firms.

The more personal financial markets of India did not preclude entrepreneurship and investment. Many huge industrial concerns were launched in the 1920s and 1930s. These include Tata Iron and Steel Company, which had an average gross block capital in the years 1924–25 to 1934–35 of 227 million rupees. G. D. Birla floated Hindustan Motors with a paid-up capital of 49.6 million and Textile Machinery Corporation with a paid-up capital of 10 million rupees. Walchand managing agency set up Premier Automobiles with a paid-up capital of 22 million rupees (Ray 1992, 61). These amounts for single companies are large compared with Bagchi's figure that I cited previously, for total cumulative investment in industrial machinery from 1900 to 1939 of 4 billion 1929–30 rupees. But all of these firms were begun by families who already had extensive commercial interests. Financing of very large concerns was restricted to those with family connections.

The amounts I quoted in the previous paragraph point to another fact. While it is not clear if the Indian economic system generated an optimal degree of entrepreneurism, it clearly generated large returns for at least some entrepreneurs. This chapter has largely focused on informal financial activity in India, as it was the preserve of indigenous Indians. The Marwari caste cluster as well as Gujarati Banias and south Indian Chettiars had been known and admired for their financial prowess for centuries. The Parsis emerged as financiers and intermediaries when the British came to India. Members of each of these groups garnered enormous wealth in the colonial period, say business historians. But it is difficult to measure the wealth associated with private, informal banking and trading. Many of the banking families, however, added industrial concerns to their holdings by the end of the colonial period, and these are more easily measured. The Tata's are the most well known of the Parsis entrepreneurial families. In 1939, the family's publicly held industrial holdings were worth 620 million rupees (equivalent at the time to US$207.5 million). This was the single largest business group in India of any nationality. It remains so today. The next richest Indian family group, then and today, is that of the Marwari Birlas. The family industrial holdings were worth 40.9 million rupees in 1939. The Gujarati Banias were represented by Lalbhai Kasturbai, among others. His family's holdings were 23.3 million rupees in 1939. The families were the main shareholders in these companies, but not the only ones. On the other hand, the value of publicly traded companies represent just a subset of each family's wealth. Consequently I believe these values are a rough indicator of the orders of magnitude of Indian family wealth.14

This chapter began with the statement that India was and is poor. The wealth of individual families does not contradict that assessment. It does, however, suggest a puzzle. If the legal and government institutions put in place by the British in colonial India cannot be responsible for the general level of poverty, at least in that period, and if during the colonial period India had a large, integrated financial structure, and a supply of clever, well-remunerated entrepreneurs, what limited Indian growth? I cannot answer that question completely. But the evidence presented here suggests several points that are important. First, the caste system, despite being so widely condemned, probably facilitated the initial industrial development of India by providing financial and managerial resources at low transactions costs to an absolutely large number of entrepreneurs. At the same time, however, the personal, caste-based nature of the Indian system almost certainly hindered the involvement of a much larger set who could have potentially become entrepreneurs. It was not that individuals were restricted from being entrepreneurs because they had been born to the “wrong” caste. The Indian social system was actually much more fluid than many people suppose, and wealth and success were valued by all, and in some sense, open to many. Members of trading castes, however, would have had preferred access to the informal financial networks of India. Their preponderance among early-twentieth-century industrialists suggests that that access gave them an advantage. As I mentioned earlier, there is an emerging interest among economists in the effect of institutions that provide wide access to opportunity. A prime historical example of its good effect is the, appropriately described, broad-based nature of entrepreneurism in early economic growth in Holland, as documented by the chapter in this volume by Oscar Gelderblom. India may well represent the obverse. Thus, one potential explanation for India's slow growth is that limited access to financial capital for the great majority of Indians may have led to a misdirection of their energy and talent. India has had many justly famous entrepreneurs. Perhaps what may have been more important in India's past record of slow growth is the many anonymous individuals who remained outside the network, and thus faced lower ex ante payoffs and, therefore, lessened incentives for entrepreneurism.

Notes

This chapter was originally prepared for the History of Entrepreneurship conference held at New York University, October 19–21, 2006, organized by William J. Baumol, David Landes, and Joel Mokyr, and sponsored by the Kauffman Foundation. I wish to thank Howard Bodenhorn as well as all participants for useful comments.

1 Lamb 1955. Parsis are Zorastrians and not Hindus. But the caste system so permeated traditional India that the social relations of even non-Hindu groups exhibited certain caste-like features. Thus scholars speak of Moslem “castes” and Christian “castes” in India.

2 A major work by Tripathi (2004) discusses the history of entrepreneurship in India from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. His book well illustrates the position of power and respect enjoyed by successful businessmen in India.

3 Roy 2002; for the colonial data and International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics Online for the data 1994–2002.

4 Ray writes that though some had thought that the term hundi was a corruption of Hindi or Hindu, that is incorrect, and that the word is instead a derivative of the Sanskrit hundika, which itself is derived from the root verb hund, meaning “to collect” (Ray 1988, 305).

5 Jain notes that some moneylenders took deposits from their “clients” though this was on a very small scale (1929, 35). Before the Assam PBEC, an agriculturist moneylender noted that he accepted deposits (Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee [Assam] 1930, 2:158). Baker notes that in evidence before the Madras PBEC, it was reported that local moneylenders accepted deposits “as a social obligation,” not because they needed them for their business (1984, 280).

6 Tripathi notes that one difference between the mahajans and a caste panchayat is that the bankers were actually from several different castes. The panchayat, though, was the model for the mahajan (Tripathi 2004, 22 and n. 28).

7 Jain 1929, 39–42 for Gujarat; Provincial Banking Enquiry (Bombay) 1930, 3:506. This might suggest that the guilds acted as cartels. Perhaps they did. As will be discussed in a later section, however, the rates they set were strongly influenced by the rates of the Imperial Bank of India.

8 Bodenhorn 2000. I have borrowed the concept of comparing correlations from Bodenhorn, who attributes it to McCloskey. The idea is that we a priori identify an “integrated market,” and then compare the degree of integration of the market for which we are less certain about to the degree of integration we have a priori identified as “integrated.” I should also note that the Indian data are monthly, and Bodenhorn's annual. I also constructed annual correlations for the Indian data, and as one would expect, these correlations are even larger.

9 Srinivas 1962, 70. I should note that I use the word caste because it is the one more familiar to the general reader. But throughout, I am referring to one's obligations to jati members, as was Srinivas in this quote. The caste system is loosely based on the four varnas of Brahmanas (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors and aristocracy), Vaishyas (merchants) and Shudras (the servants of the others). Castes either belonged to one of these four, or were below these in the hierarchy; these latter are the so-called untouchables, or scheduled castes. In practice, these four varnas are less important than were the relationships among and between the quite numerous subcastes, or jatis. While one would typically find a member of each of the four main castes in each village in India, the subcastes were specific to each region. The jatis were the true functional unit of the caste system. They were, for example, the endogamous unit. And the obligations of jati members to each other were much stronger than were the obligations of caste members more generally. (See, among others, Hutton 1963.) I should also mention that the caste system was not a monolithic institution. It operated differently in the different parts of India. But the characteristics I am interested in, i.e., one's obligation to the group and the punishment for violating group norms, are fairly universal.