Chapter 6

The Golden Age of the Dutch Republic

THE DUTCH GOLDEN AGE is an icon of premodern economic growth. The revolt against Philip II and his successors in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries coincided with an unprecedented economic boom and cultural flowering. Between 1580 and 1650 the Dutch became the dominant player in European trade—an achievement based on their large-scale commercial agriculture and fisheries, market-oriented manufacturing, and low-cost shipping services. In addition, a combined military and commercial effort allowed the Dutch colonial companies, VOC (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) and WIC (West-Indische Compagnie), to establish a dense network of trading posts in Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

The Dutch Republic was a country of entrepreneurs, a society in which the livelihood of a considerable number of men and women depended on their judgmental decisions about the buying and selling of goods and services.1 These entrepreneurs included not just merchants involved in long-distance trade, but also shipmasters, fishermen, millwrights, farmers, artisans, and shopkeepers. Except for the directors of colonial joint-stock companies and the managers of a few large farm estates and manufacturing firms—men who received a fixed reward for their judgmental decisions—the income of these entrepreneurs depended on the profits or losses they made in the marketplace.

The origins of this entrepreneurial class predate the Golden Age by at least two centuries. From the late fourteenth century the Dutch were involved in commercial dairy farming, the importation of bread grains, and the export of herring, beer, and textiles. In the first half of the sixteenth century the commercialization of agriculture continued with the development of stockbreeding and peat digging, while merchants and shipmasters in the coastal provinces established a regular trade with Flanders and Brabant, the Baltic Area, England, and the Atlantic coasts of France and Spain. In short, the entrepreneurial success of the Golden Age was to a large extent the realization of an already existing potential.

Even so, important changes did occur after the independence of the United Provinces. The removal of thousands of laborers and artisans from the southern provinces in the 1580s and 1590s stimulated the manufacturing of textiles, refined sugar, weaponry, paintings, books, maps, and myriad other luxury wares. The fall of Antwerp in 1585 and the emigration of at least a fifth of its merchant community added considerably to the scale and scope of the Amsterdam market. Finally, without the independence from the Habsburg Empire, the establishment of direct trading links between the Low Countries and Africa, America, and Asia would have been inconceivable.

This chapter analyzes the contribution entrepreneurs in agriculture, industry, and trade made to the Dutch Golden Age. Were these men and women with outstanding personal qualities, either in terms of human, social, or financial capital? Or was it a favorable set of legal, political, and economic institutions—either inherited from an earlier period or copied from more advanced economies—that allowed more men and women than elsewhere in Europe to set up their private businesses, market goods and services, and manage the risks entailed by their reliance on market exchange? Or was there nothing special about either entrepreneurs or institutions, with the Dutch simply taking advantage of economic opportunities foregone by potential competitors caught up in economic crises and continuous warfare elsewhere in Europe?

A Country of Entrepreneurs?

In most accounts of the Dutch Golden Age the contribution of entrepreneurs revolves around the economic achievements of a relatively small group of highly successful merchants and manufacturers.2 The usual suspects include the rich and well-connected Flemish and Portuguese merchants who settled in Amsterdam at the turn of the seventeenth century; the skilled instrument makers, cartographers, schoolmasters, book printers, sugar refiners, painters, and silk weavers from Flanders and Brabant who followed in their wake; and, in the later seventeenth century, the experienced Huguenot silk weavers from France.3 Very few historians of entrepreneurship have considered the many other men and women who made judgmental decisions about the buying and selling of goods and services.4 And yet their number must have been in the tens of thousands.

A very crude measure for the number of active entrepreneurs would be the urbanization ratio of the Dutch Republic. By the mid-seventeenth century some 40 percent of the total population lived in towns, albeit with strong regional differences. Urbanization in Holland reached an impressive peak of 60 percent while it did not exceed 25 percent in several of the inland provinces (De Vries and Van der Woude 1997). Such a high level of urbanization would have been unthinkable without entrepreneurs. First there were the numerous commercial farmers, wholesalers, retailers, and shipmasters responsible for the food supply of the town populations.5Then there was a group of self-employed artisans and shopkeepers who supplied households with all kinds of consumer durables (Posthumus 1908, 269–70, 274). Finally, the Dutch economy thrived on the imports and exports of agricultural produce, manufactures, and colonial wares—activities that further stimulated entrepreneurship in town and countryside.6

Yet to claim that the Dutch Republic was a country of entrepreneurs requires more persuasive reasoning. We need to estimate their numbers. An appropriate starting point would be the countryside of the coastal provinces Holland, Friesland, and Zeeland in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, when soil compaction dramatically changed the economic outlook of the rural population.7 Peasants who had previously grown bread grains shifted their production to dairy, meat, and industrial crops such as hemp and madder that were subsequently marketed in the Dutch beyond. At the same time they took on by-employment as peat diggers, brickworkers, fishermen, and shipmasters, the result of which was a surprisingly modern-looking rural economy with at least part of the peasant households earning their living with a combination of wage labor and entrepreneurial activities (Van Bavel 2003, 2004).

A first approximation of the number of rural entrepreneurs in the countryside can be obtained by looking at the number of households involved in dairy farming—perhaps the single most important agricultural sector. The Italian chronicler Lodovico Guicciardini wrote in 1567 that the annual production of cheese and butter in Holland equaled the value of Portuguese spice imports (Guicciardini et al. 1567). Preliminary calculations, taking into account the small size of landholdings, and the limited number of cows per household, suggest that around 1500 between one-half and two-thirds of the total number of households in Holland were involved in commercial dairy farming. Most of these farms were productive enough to secure full employment for the family and in some cases even additional maids or farmhands (Van Bavel and Gelderblom 2010). The total number of rural entrepreneurs in Holland was higher still. For one thing, the peasant households relied on wholesalers and retail traders in villages or small towns to supply their food, clothing, and farm supplies such as dung, hay, fodder, equipment, and breeding stock.8 For another, there were hundreds of herring fishers and shipmasters, as well as a small but thriving contingent of entrepreneurs who ran paper and sawmills, salt refineries, madder kilns, brick-and tileworks, and shipyards on the banks of the major rivers and lakes (Van der Woude 1972; Van Bavel and Van Zanden 2004).

But how many were these entrepreneurs? A detailed reconstruction of the wealth and principal occupation of heads of households in the small town of Edam, north of Amsterdam, allows a tentative estimate.9 In 1462 Edam, with a population of 2,400, counted at least 200 fishermen, shipmasters, wholesalers, shipwrights, and well-to-do peasants (with five cows or more). That is not including bakers, butchers, fishmongers, and the like. If we assume that the total workforce made up two-thirds of the population, the share of this class of entrepreneurs in this early period was 12.5 percent. In 1560 the number of town dwellers had grown to 3,750, but now there were fewer (160), rather than more, entrepreneurs with a comparable economic status—a development that might be explained by the decline of the number of town dwellers that owned large farm holdings, a greater scale of operations in industry, and perhaps a stronger hold of Amsterdam merchants and shipmasters over shipping and trade.

Now the highly commercialized countryside of Holland was a world apart, even in the Dutch Republic.10 Only parts of the coastal provinces of Friesland and Zee-land went through a similar process of agricultural specialization early on.11 The inland provinces retained large areas where agriculture was dominated by subsistence farming, and where urban entrepreneurs offered only a limited set of goods and services (Brusse 1999). Still, even here one finds highly productive agricultural regions dominated by small numbers of wealthy farmers. In the Guelders river area, for example, the early development of term leases, the obligation of landowners (noblemen, religious institutions, and town dwellers) to fund repairs, waterworks, and physical infrastructure, made for high reinvestment ratios (Van Bavel 2001). This stimulated the growth of a small group of large tenants who used their high incomes from farming to fund short-term investments in livestock, seeds, implements, and labor. Using local labor surpluses created by the ever more skewed distribution of landownership and leases, they were able to step up production for the market in the course of the sixteenth century.

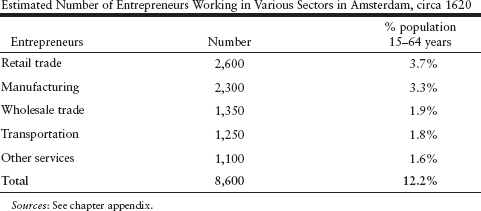

TABLE 6.1

Still, the most obvious place to look for entrepreneurial activity is in the major ports and manufacturing centers that were actively involved in domestic and international trade. These included Leiden, Haarlem, Rotterdam, Middelburg, several smaller ports in Holland and Friesland, and of course the city of Amsterdam. The very rich historiography of the latter port allows us to estimate the number of entrepreneurs that worked here in the first quarter of the seventeenth century (table 6.1).

The largest group of entrepreneurs in Amsterdam were its 2,600 shopkeepers. These were the butchers, bakers, grocers, cobblers, and traders in wine, fish, and fruit who sustained an urban population of 120,000 in 1620. There were about as many manufacturers, part of whom also catered to the needs of the local people. However, besides the master artisans that produced clothes, shoes, pots and pans, and other household items, there were shipwrights, gold-and silversmiths, painters, and printers, working for local and foreign customers alike. Amsterdam's leading role in international trade is reflected in the large number of merchants and shipmasters, as well as the brokers, hostellers, and notaries that supported the commercial sector. Together, the various groups of entrepreneurs made up an estimated 12.5 percent of Amsterdam's working population. If this relative share is in any way representative for other towns in the Dutch Republic, already in 1600 the total number of urban entrepreneurs may have been as high as 45,000, rising to over 60,000 in 1650.12

Entrepreneurs and Innovation

The high rate of self-employed men and women in towns and villages was a salient feature of the early modern Dutch economy. But were these all entrepreneurs in the sense of Joseph Schumpeter's theory about creative destruction? Surely, the majority would have responded to new economic opportunities rather than created them. Indeed, classic accounts of how entrepreneurs may have spurred economic change in preindustrial Europe all favor a more restrictive definition, as they focus on the specific qualities of a few individuals, including their management skills, technical capabilities, commercial networks, financial capital, or even a capitalistic spirit.13

This interest in the personal attributes of a few exceptional entrepreneurs is echoed in the Dutch historiography of the Golden Age. Notably the Flemish merchants and artisans immigrating from the southern provinces after 1585 have often been described as more highly skilled, richer, better connected, and more daring than their Dutch counterparts—a reputation they share with the much smaller group of Portuguese Jews arriving in the same period.14 A case in point are the Antwerp merchants Isaac Lemaire and Dirck van Os, both of whom figured prominently in the expansion of trade with Russia, Spain, and Italy; the spice trade with the East Indies; and the huge land reclamations north of Amsterdam. The fact that Lemaire's investments in the VOC led to multiple lawsuits, bankruptcy, and ultimately his departure from the city has only added to his reputation.15

It seems probable enough that a country catapulted into a position of economic and technological leadership achieved this status through a massive mobilization of innovative entrepreneurs. One example would be Cornelis Cornelisz. van Uitgeest, a farmer and millwright in a village near Amsterdam who built the first wind-driven sawmill in 1594 (De Vries and Van der Woude 1997, 345–49; Bonke et al. 2002). The name of Willem Usselincx is inextricably linked to the exploration of new markets in the Americas after 1600 (Den Heijer 2005). In the first decade of the sixteenth century Lambert van Tweenhuysen initiated whaling expeditions in the northern seas.16 In 1618 Louis de Geer and Elias Trip started to set up extensive ironworks in Sweden. But even if these men all had exceptional business acumen, their endeavors fall short in explaining the exceptional growth of the Dutch economy.

In many sectors of the economy important technological and organizational changes occurred long before the Golden Age. This is true for improvements in the design of vessels used in the herring fisheries and ocean shipping (Unger 1978); the processing of foodstuffs such as butter, beer, and herring;17 the opening up of new markets in Scandinavia, Poland, France, and the Iberian Peninsula (Van Tielhof 2002; Posthumus 1971; Lesger 2006); water management in the polders of Holland (Van Tielhof and Van Dam 2007; Greefs and Hart 2006); the introduction of peat as an energy source in manufacturing (Van Tielhof 2005); and finally the development of rural industries such as the processing of red dyes from madder, salt refining, and brick making.18 It is important to note that very few of these innovations are linked to particular engineers or entrepreneurs. Even very famous attributions, like that of herring-gutting to Flemish fisherman Willem Beukelszoon, are currently disputed (Doorman 1956).

This lack of names linked to innovations before the Golden Age is not just an artifact of an incomplete historical record. It also reflects the incremental nature of technological change.19 This is visible, for example, in the increasingly competitive production of butter and cheese in Holland and Friesland. The growing quantity and gradually improving quality of dairy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was the result of changes in the keeping, feeding, and breeding of the cattle that led to higher milk yields per cow, and concomitant adaptation of the interiors of farm buildings, the utensils for churning and cheese-making, and the actual preparation of butter and cheese. As a result, not a single peasant, or his wife, has been credited with this achievement. In fact, even the cattle-driven churn mill that took over much of their handwork in the seventeenth century remains without a known inventor (Boekel 1929, 42n).

Meanwhile, the technological advance of the Dutch Republic was driven by a constant interaction between economic sectors (Davids 1995, 2008). One such web of innovation can be spun around the Dutch windmill (Davids 1998). After a first adaptation of grain mills to the needs of water management in the fifteenth century, windmill technology spread further to industrial mills for oil, paper, and timber during the Golden Age. Saw milling in turn stimulated the growth of Dutch shipbuilding, with all its improvements in ship design. The Dutch competitiveness in shipping and trade in turn was related to improvements in navigational instruments and maps, and the introduction of the partenrederij, a limited liability contract first used in shipping but eventually also in paper and sawmills (see infra, “Property and Contract Law”).

The exchange of goods and services between regions also contributed to the advance of individual sectors. This is most apparent from the growing interaction between the northern and southern provinces of the Low Countries in the course of the sixteenth century. In exchange for the import of high-value manufactures and capital from the southern provinces, Holland exported large quantities of cheese, herring, and peat, and they organized a transit trade in grain, hides, salt, and wine from the Baltic area and the Atlantic coast of France. The result was a process of ongoing economic specialization (Lesger 2006; Gelderblom 2003a).

Most innovations in products, markets, and production processes in the Golden Age cannot be traced to individual entrepreneurs either. But there are a few exceptions, most notably in the first few decades after the fall of Antwerp in 1585. These include the first merchants trading with Italy, Russia, and West Africa, the initiators of the trade with Asia and America, the shipwright who built the first fluytschip, the printers of better maps, the inventor of the ribbon loom (Vogel 1986), and the first producers of luxury items such as glass, tulips, and ivory combs. Sometimes one can discern a small group of men responsible for the introduction of new products and techniques, like the Flemish schoolmasters who taught double entry bookkeeping in the principal ports of Holland and Zeeland, the owners of the earliest sugar refineries, or the first jewelry merchants in Amsterdam (Davids 2008).20

This string of innovations in industry, shipping, and trade at the turn of the seventeenth century was at least partially due to the political turmoil of the time. The disruption of the economy of the Low Countries in the early decades of the Dutch Revolt was such that deficient supply of goods and services raised prices, inflated profits, and reduced risks for the beginning entrepreneurs that most of the immigrants from the southern provinces were. At the same time, the entrepreneurs identified with the introduction of new markets, products, and technologies benefited from the knowledge and skills of migrant workers. For example, the Flemish and Portuguese jewelry merchants who settled in Amsterdam after 1595 put out their production to highly skilled goldsmiths and diamond cutters from Antwerp. The owners of the first sugar refineries hired experienced German and Flemish masters to supervise production while limiting their own role to the purchase of raw materials, and the sales of sugar. Similar combinations of skilled workers and wealthy merchants existed in the production of textiles, leather, salt, madder, and tobacco.21

The organization of these urban industries also bears out the importance of the institutional framework that shaped manufacturing. The craft guilds in Dutch towns allowed merchants to pay master artisans a wage for the production of luxury items, and thus appropriate a considerable part of their value added. Urban craftsmen accepted these arrangements, at least in the early phases of economic expansion, because their retained earnings were high enough for some of them to rise through the ranks and become merchants themselves. This is borne out by several artisans who started as goldsmiths in Amsterdam in the late sixteenth century, to become wealthy jewelry merchants by the end of their careers.22

Urban magistrates also tried to lure beginning entrepreneurs to their towns, especially in the boom years between 1580 and 1620. Silk weavers, glassmakers, sugar refiners, and various other manufacturers benefited from tax exemptions, cheap (child) labor, favorable loans, guaranteed sales, or even entire production facilities.23The main interest of the municipalities was in import substitution, employment for the unskilled or urban poor, and the support of ailing industries. The effect of their policies is hard to measure in an environment where many industries prospered anyway. On the other hand, several entrepreneurs left their host town within a few years, or even failed spectacularly, as with the attempts to grow mulberry trees to substitute for Asian silk imports (Eerenbeemt 1983, 1985, 1993).

A far more targeted stimulus for entrepreneurial activity was the patenting system introduced by the States of Holland in the late sixteenth century (Davids 1995; De Vries and Van der Woude 1997). In textiles, milling, shipping, and several other sectors, this system allowed the producers of new knowledge to secure a share of the profits that issued from the application of their insights. Especially between 1580 and 1650 patents gave hundreds of talented craftsmen and engineers the possibility of reaping the fruits of their ingenuity. Another instrument used by the government to stimulate innovation was the granting of monopolies for the entry into new markets or the sale of new goods. These rights to exclusive purchases and sales—appropriately termed octrooien, just like the patents for technical novelties—created similar financial rewards for innovators (Davids 1995). The best-known examples are the joint-stock companies trading with Asia and America, but monopoly rights were also granted to the whalers who worked near Greenland (Hacquebord 1994), to Flemish drapers in Leiden (Posthumus 1939), and to the producers and traders of such an ephemeral product as civet, a smelly substance used for the making of perfume that was “harvested” from African cats (Prins 1936). With the exception of the colonial companies none of these monopolies survived after 1650, but in later years Dutch entrepreneurs did obtain similar rights from foreign rulers who tried to stimulate their own economies (Eeghen 1961).

The exclusion of competitors through cartels and monopolies is ill-reputed because the rents that are created are believed to exceed the profits necessary for the remuneration of labor and capital. However, the practical use of the Dutch octrooien was in fact in these rents: an income that entrepreneurs could use to cover their start-up costs, and some of the risks involved in the new activities.24 This financial rationale mirrors Joseph Schumpeter's understanding of entrepreneurship and points to a final and perhaps most important explanation for the wide application of new knowledge during the Dutch Golden Age: the greater ability of entrepreneurs to mobilize capital for investments in agriculture, industry, and services.

Riches

Particularly puzzling about the Dutch Golden Age is the almost complete absence, as late as 1580, of entrepreneurs wealthy enough to finance large investments in agriculture, industry, and trade. Before the Dutch Revolt brewers, textile manufacturers, and merchants in the northern part of the Low Countries seldom owned more than a few thousand guilders (e.g., Brünner 1924). For example, in 1498 only five drapers in Leiden—at the time the principal producer of woolen cloth in Holland—were worth more than 5,000 guilders (Posthumus 1908, 278). Similarly modest was the capital of the merchants and manufacturers operating in mid-sixteenth century Holland and Zeeland. Habsburg tax receivers in 1543 estimated the capital invested by entrepreneurs from Amsterdam, Delft, Middelburg. Flushing, and Veere at 6,000 guilders or less.25 These estimates pale into insignificance compared with the tens of thousands of guilders, and sometimes considerably more, owned by the richest foreign and local merchants in Antwerp at that time.

It thus comes as no surprise that many historians have argued that economic expansion only truly began once wealthy merchants from the southern provinces fled to the north. Their capital would have allowed the rapid expansion of trade within Europe, the foundation of the colonial companies VOC (1602) and WIC (1621), and the large turnover realized from the very moment the Bank of Amsterdam was established in 1609. However, a closer look at the wealth of these immigrants shows that the vast majority came to Amsterdam with little or no money. Even the largest investors in the VOC started with modest capital of only several thousands of guilders (Gelderblom 2000; see also Gelderblom 2003a). The limited data available on the wealth of other immigrant merchants, notably Germans, Portuguese Jews, and Englishmen, show a similar picture.

This is not to say that these entrepreneurs made no contribution to the growth of the Amsterdam market. Quite the contrary. In Amsterdam the immigrants from the southern provinces and their children made up a third of the merchant community between 1580 and 1630. Their personal wealth was in keeping with this share, and hence their arrival raised the capital available for investment by some 50 percent. However, if these were small capitals to begin with, how can one explain the explosive growth of the Dutch economy between, roughly, 1590 and 1620?

One explanation could be that the closure of the Scheldt, and the warfare that occupied the Habsburg Empire, France, and England created windfall profits for merchants in the United Provinces willing to take the risks and trade with the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, and the Levant. However, in all these markets the Dutch had to compete with English and French traders. At the same time, returns on investment in the highly competitive Baltic run—the traditional Dutch stronghold—were never higher than 5 or 10 percent either (Van Tielhof 2002; Gelderblom 2000).

A far more important lever of riches was the trade with the East Indies. By 1608 the cumulative returns of the early companies sailing from Amsterdam between 1595 and 1602 amounted to 15 million guilders, against cumulative investments of 9 million—including a 3.6 million investment in the local chamber of the VOC in 1602. The Dutch East India Company proved at least as lucrative in the following decades. In 1631, thirty years after its establishment, total dividend payments stood at 11 million guilders. In other words, Amsterdam's investors in the East India trade accumulated seventeen (6 plus 11) million guilders in less than forty years. To put this figure into perspective: the assessment for a 0.5 percent wealth tax in 1631 yielded an estimated wealth for the entire population of 66 million guilders—35 of which can be traced to the city's merchant community. Now even if this tax did not include movable goods and taxpayers played down their wealth, the contribution of the East India trade to Amsterdam's wealth was formidable. But still, how did merchants with modest means manage to fund such huge investments to begin with?

Property and Contract law

An entrepreneur with only limited financial means has to rely on others to fund his business. In preindustrial Europe the preferred means to acquire additional capital was to rely on relatives. It was no different in Dutch agriculture, industry, shipping, and trade. On the one hand, fathers, brothers, uncles, and cousins worked together in partnerships. On the other, relatives with money to spare who did not want the exposure to commercial risks could deposit their funds with enterprising family members in exchange for a fixed return on their loans. Through marriage and long-standing friendship it was often possible to widen this circle of trusted partners and creditors further.

The financial challenge for entrepreneurs in the Dutch Republic at the beginning of the Golden Age was that the wealth of their relatives and friends was limited, while potentially profitable investment projects abounded. The only possible way for them to take advantage of these opportunities was to find outside investors—partners with whom to share profits and losses, or lenders willing to part with their money in return for a fixed reward. However, without personal relations to rely on, it was more difficult for these outsiders to establish beforehand the trustworthiness of potential associates or debtors, as it was to secure their compliance after a contract was signed. This put a premium on the development of debt and equity contracts that allowed the transfer of funds between strangers.

A first solution was the adaptation of the general partnership through the writing of company contracts.26 The specification of the duration and purpose of a joint venture limited the liability of the partners to transactions that fell within the terms of their agreement. Notarial deeds that survive for Amsterdam show that these company contracts were used in a variety of economic sectors. However, the spread of this very basic limitation of liability may have been much wider, because by the end of the sixteenth century it sufficed for partners to record such agreements in private (e.g., Moree 1990). What company contracts could not do was limit the liability for debts partners incurred within the boundaries of their agreement. In other words, a creditor of a firm could always claim an outstanding debt from any single partner of the company—leaving it to this particular partner to share the burden with the others. This is why even company contracts were often written between entrepreneurs with social ties between them.

A way out of this situation was found with the creation of the partenrederij—a contractual arrangement for the joint ownership of vessels either for fishing, transportation, or trade (Riemersma 1952; Posthumus 1953; Broeze 1976–78). In what seems to have been an adaptation of the generally accepted limitation of losses at sea to the total value of a shipping enterprise, the partenrederij limited the liability of each of the shareholders to the value of his investment. It was not uncommon for the ownership to be divided into eight, sixteen, thirty-two, or even more shares, thus giving even owners of the smallest wealth the opportunity to participate. In addition, the contract allowed for the delegation of the management of the company to one or two owners, and thus it could potentially serve a much larger crowd of investors. It remains unclear when and where this contractual form was first introduced, but certainly by 1450 it was common practice in the fisheries and shipping in the Low Countries and northern Germany.

In the Golden Age the partenrederij spread to several other sectors with high capital requirements, including paper mills, sawmills, peat exploitations, and most important, the first ventures to West Africa and Asia.27 All of the early colonial companies that sailed from Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Middelburg, and a few other ports in the 1590s were owned by dozens of shareholders, several of whom resold part of their investments to others. Indeed, the financial organization of the VOC closely resembled that of the partenrederijen, albeit with one crucial difference: investments in the VOC were understood to be used for more than a single voyage. Indeed, the first company charter stipulated a ten years’ term for repayment of the initial shares, and this term was then prolonged several times to create a permanent joint-stock company effectively.

By 1650 equity finance with limited liability was common practice in Dutch ocean shipping, the herring fisheries, whaling, colonial trade, and a few capital-intensive manufactures, but not in other parts of the economy (De Vries and Van der Woude 1997). In agriculture, wholesale trade, retailing, and craft production entrepreneurs continued to work with their own funds or in small partnerships. A further extension of their working capital, if needed, was achieved through medium- or long-term loans, mostly deposits from relatives, but also funds from outsiders. However, in order for entrepreneurs to obtain credit from strangers, they had to pledge some kind of collateral to assure the creditor that he would get his money back.

Interestingly, one of the oldest forms of such collateral was still based on personal relations: namely the use of guarantors who had both sufficient knowledge of the financial position of the debtor, and a credible reputation known by the creditor. Provided the guarantor could easily be found by the creditor in case of default, the guarantee was a great help in securing repayment.28 How much credit was backed by personal guarantors is impossible to say, but notarial deeds suggest it was widely used in Dutch trade, industry, and agriculture before and during the Golden Age.

Entrepreneurs who could not, or did not want to, rely on the creditworthiness of relatives and close friends could use their own property as collateral instead. One obvious possibility was use of their own products to secure loans. This is, of course, the principle underlying the postponed payment of goods, but it was also used for longer-term credit operations. Peasants in Holland and Zeeland, for example, signed forward contracts for their grain, madder, and butter. Urban craftsmen and retailers left their property with pawnbrokers and banken van lening to obtain ready money.29However, the use of merchandise as collateral had serious limitations. Creditors had to assess the exact quality of the goods, and they had to store them in a safe place in order to prevent material deterioration, damage, theft, or embezzlement by the borrower (Gelderblom and Jonker 2005). Especially the latter requirement made it difficult to sell goods on short notice. Furthermore, leaving goods in the hands of a lender was of little use to entrepreneurs who wanted to be able to sell them at short notice.30

A more appropriate means to obtain long-term funding was to sell annuities secured by real estate. This instrument was first used in the Low Countries in the thirteenth century, and its importance increased considerably over the next centuries (Zuijderduijn 2009). Entrepreneurs who needed funds sold the right to an annual income (rente), in return for which they received a principal sum. For savers with excess funds who wanted to secure a future stream of rents, but were unwilling to bear high risks, annuities were an attractive proposition. For one thing, the rente was not considered usurious. For another, the value of the underlying real estate was rather stable, especially once a growing number of houses were built in brick instead of timber. Furthermore, legislation by Charles V in the early sixteenth century gave creditors who wanted to liquidate their claims the right to sell them to a third party (Van der Wee 1967; Gelderblom and Jonker 2004). Finally, all real estate transactions and related credit operations had to be registered by the magistrates of towns and villages.31 This measure was taken for fiscal purposes, but the registers obviously contained all the information renten buyers needed to establish the creditworthiness of their debtors—information that could be used in court in case of default.

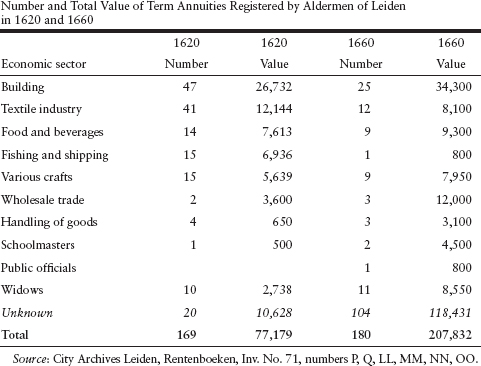

Evidence from various parts of the Low Countries suggests that annuities were an important means for small entrepreneurs to expand their operations. In Holland and Brabant urban registers of private debt have survived from the late fifteenth century onward.32 A case study of the jewelry trade shows that in Antwerp between 1530 and 1565 goldsmiths and diamond cutters from Flanders, Brabant, and Holland sold annuities to establish themselves as independent jewelry merchants.33 A preliminary analysis of the annuities registered by the town magistrate of Leiden in 1620 and 1660 reveals a similar pattern (table 6.2).

In 1620 some 170 small entrepreneurs in Leiden sold term annuities with a total value of 77,000 guilders. Half of these men worked in the textile and building industries, while another third were craftsmen, retailers, shipmasters, and fishermen. At 450 guilders the average value of all the annuities was rather low, especially when compared to the few that were sold by wholesale traders (at 1,800 guilders on average). Forty years later the number of entrepreneurs who used this credit instrument had not grown much, but the value of their separate claims had almost tripled. Builders, textile producers, and other craftsmen still dominated the body of lenders.

Annuities, however, had their limitations when it came to funding businesses. Besides mandatory registration, interest rates were fixed at 6.25 percent, which was a competitive rate in the sixteenth century but less and less so in the seventeenth century (Gelderblom and Jonker 2004). This problem was eventually resolved by a lowering of the statutory rate, but there were other difficulties. Most important, one could only fix so many renten on a particular piece of real estate—a limitation that would be felt in the later seventeenth and the eighteenth century when the towns no longer expanded, and rental values stabilized or even declined. Thus, in addition to annuities entrepreneurs had a real need for other medium- or long-term loans that did not depend on their ownership of real estate. But what could they pledge as collateral?

In the mid-sixteenth century merchants on the Antwerp money market began to sell promissory notes, also known as bills obligatory or IOUs. These credit instruments, which were also used in other countries, were transferable, interest-bearing loans with a standardized maturity of three, six, or twelve months (Ehrenberg 1896, 25; Van der Wee 1967, 1080–81; Van der Wee 1977). After 1585 the large-scale emigration of Antwerp merchants brought the bill obligatory to Amsterdam. The advantage of bills obligatory over both annuities and family deposits was that creditors could determine in advance when they wanted to get their money back. For borrowers this was not a problem, for they could contract with a variety of lenders and differentiate the dates at which their loans matured.34 What is more, in practice many bills were rolled over on expiry, effectively creating a long-term credit instrument (Gelderblom and Jonker 2004).

TABLE 6.2

The only remaining problem, at least for the lenders, concerned the collateral. Borrowers simply pledged their persons and goods without any further specification. Even if individual bills represented only small amounts of money—often no more than 1,000 or 1,500 guilders—liquidation of a bad debt might be problematic with such general collateral. The transferability of IOUs, firmly established by an imperial ordinance, did not really solve this problem because only merchants familiar with a debtor's financial position would be willing to take over a debt. Hence Charles V's additional ordinance of 1543 that limited the use of the IOUs to the merchants active on the Antwerp Exchange (Gelderblom and Jonker 2004).

It was the foundation of the Dutch East India Company in 1602 that eventually created the ideal collateral for loans: the VOC share.35 Merchants in Amsterdam, who had begun using Antwerp-style IOUs to attract external funds for their businesses in the 1590s, almost immediately recognized the potential of the share, as “a claim on a company known to all; very liquid, so easy to sell in case of default; with daily price quotations for quick valuation; and with ownership easily ascertained” (Gelderblom and Jonker 2004, 660). Borrowing on the security of shares—even today a widely used financial technique—allowed merchants with no personal ties to engage in credit operations, for the lender could always attach and liquidate the share. It did not take long for this technique to take root among the merchant community at large.

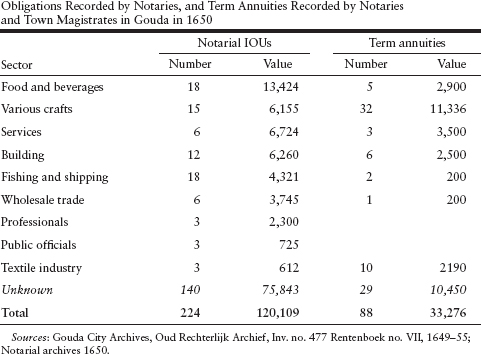

TABLE 6.3

But how could smaller entrepreneurs who did not own VOC shares secure additional funding for their businesses? This question is at the heart of current research on the evolution of financial markets in the Dutch Republic. One very tentative answer based on data collected for one town in one year points to the role notaries may have played in matching supply and demand for funds. The protocols that have survived of notaries in Gouda in 1650 show their writing of 220 obligations for a varied crowd of artisans, shipmasters, retailers, and other small businessmen. A comparison with the total value of term annuities sold in the same year (mostly registered by the town magistrate, but sometimes also by notaries) suggests notarial credit may have filled a void, as it is known to have done in early modern France.36But frankly this remains speculation, given the sparse data now available.

Risks

Making judgmental decisions about the marketing of goods and services implies risk—and not just unexpected price fluctuations due to adverse market conditions. Dutch entrepreneurs were also confronted with natural disaster, warfare, crime, and dishonest behavior of partners and employees (Van Leeuwen 2000). Farmers regularly suffered from extreme weather, diseases, and warfare. Merchants, shipmasters, and fishermen encountered shipwreck and privateering raids. Wholesalers, retailers, and manufacturers had to deal with thieves, nonpaying clients, and suppliers tampering with the quality of their wares. Dutch entrepreneurs, like anyone else, wanted to prevent such misfortune, or at least to secure compensation for losses that did occur.37

Local and central authorities in the United Provinces played a crucial role in the prevention of opportunism, violence, and, one might even argue, natural disaster (Gelderblom 2003). Obviously Dutch rulers realized they could not stand in God's way, but nevertheless determined attempts were made to try to limit the damage of nature's single biggest threat: water. With the creation of water boards in the late Middle Ages, the Dutch created an efficient administrative apparatus to prevent inundation of the continuously subsiding lowlands of the coastal provinces. Landowners and tenants were initially forced to contribute their labor and later on mostly their money to build and maintain canals, dikes, sluices, and windmills. Even if neighboring water boards sometimes wrangled about each other's lack of effort, the system by and large succeeded in stabilizing the quality of the soil (Van Tielhof 2009).

The prevention of violent assaults on entrepreneurs in the Dutch Republic also depended on government intervention. Already in the late Middle Ages towns had secured a local monopoly on violence that allowed them to clamp down on robbers, thieves, and other criminals. Through persuasion and relatively mild repression the town magistrates in Holland also managed to nip in the bud the dozens of food and tax riots that broke out in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Dekker 1982). At the same time the Dutch managed to push the theater of their war of independence to the fringes of their territory, thus securing the undisturbed exchange of goods and services in the heartland, that is, Holland (Tracy 2004). Finally, the Dutch Republic was one of the first European states to command a standing navy that was used, among other things, to protect the merchant fleet (Bruijn 1993).

Furthermore, local and central rulers contributed to the prevention of cheating and slacking by trading partners, employees, and other agents. Even if Dutch businessmen displayed a persistent preference for trading with relatives and friends, their dependence on the market made business transactions with strangers inevitable (Gelderblom 2003b). Town magistrates made it easier to find honest agents through the creation of a market infrastructure and the regulation of financial and commercial intermediation. Local courts facilitated the speedy settlement of the widest possible range of business conflicts, while leaving open the possibility of appeal to a higher court (Gelderblom 2005).

A major improvement in the settlement of disputes in the Dutch Golden Age emerged from a combined effort of magistrates and entrepreneurs. On the one hand, courts began to accept account books as legal proof for disputed transactions. On the other, businessmen increasingly kept detailed accounts of their commercial and financial transactions.38 It will come as no surprise that long-distance traders in the major ports of the Dutch Republic were trained to use double entry bookkeeping. However, the habit of keeping a paper track of one's money and goods spread much wider. Farmers, textile manufacturers, and retailers also kept detailed accounts of their operations. Indeed, women were trained to do so, witness several surviving account books from the seventeenth century (Sterck 1916; Boot 1974, 32–33; Vrugt 1996). With the acceptance of these accounts in court, what was initially a monitoring device now doubled as a means to enforce contracts.

Finally, the government's role in mitigating the detrimental effect of price fluctuations differed strongly among sectors. While no entry barriers affected European trade, the two big colonial companies were given full monopolies upon their creation. In agriculture, all peasants and farmers were free to produce whatever they wanted, but urban magistrates did not shirk from regulating the supply of grain, bread, and other necessities of life, if doing so could prevent dearth. In manufacturing, some guilds used their corporate powers to exclude competitors and secure a steady income for the members, while others allowed subcontracting or production by outsiders (Prak 1994; Davids 1995; Posthumus 1908, 118–29, 275). The latter freedom certainly existed in the unincorporated industries for the processing of colonial wares, such as sugar and diamonds.

All these efforts notwithstanding, natural disaster, violence, opportunism, and price fluctuations did occur (Klein and Veluwenkamp 1993, 27–53). So entrepreneurs had to think of measures to manage these risks. One basic, though not necessarily wise, solution was to limit their exposure to the market. This was common enough in the early phases of commercialization of Dutch agriculture. While they began to produce butter, cheese, and hemp for the market, peasant households in Holland continued to provide at least part of their own food supply, while at the same time seeking additional employment in peat digging, fishing, shipping, and all kinds of menial work on bigger farms (Van Bavel 2003; Baars 1975, 28). Urban craftsmen could also combine work on their own account with wage labor for others. One example is the goldsmiths and diamond cutters of Amsterdam, who in the early seventeenth century received wages for jewelry they wrought for local merchants. To date the extent of this phenomenon of urban putting-out has not been investigated, however.

And yet the Dutch economy stands out for the relatively large number of entrepreneurs whose income did entirely depend on profits and losses made in the market. For men and women with only modest means—which certainly includes the majority of peasants, craftsmen, and retailers—the maintenance of a stable clientele could secure a steady income. Entrepreneurs with more financial scope could also try to diversify their business. This was the typical strategy for the merchants who worked in Amsterdam in the opening decades of the Golden Age. They traded on several European markets, in several products, and at the same time invested in shipping, whaling, industry, and even land reclamation. Especially shipping share companies (partenrederijen) allowed merchants with even modest means to combine investments. A similar preference for diversification can be found in agriculture, where dairy farmers used some of their land for growing hemp, and grain farmers began to produce tobacco.

Mixed husbandry was not always possible, however. In Zeeland, for example, the farmers’ basic choice was between grain and madder, both of which were crops that tied up capital for a considerable time period, with sales concentrated in the harvest season and, hence, a great sensitivity to adverse market conditions. For the production of madder a solution was found in the transfer of financial risks to urban financiers. Merchants from Rotterdam bought the madder while it was still in the field, and then, after it had been processed, sold the various qualities of red dyes to textile finishers around Holland, and abroad (Priester 1998; Baars 1975, 22, 52).

The most extensive forward trading in the Golden Age occurred in Amsterdam. Here merchants began to write contracts for the future delivery of grain in the mid-1550s. Their purchases in anticipation of expected shortages led to a public outcry, but despite government measures to prevent further transactions, forward trade continued, and in later years spread to other bulk commodities such as herring and sugar, as well as to VOC shares and tulips. Still, it took a sufficiently large group of wealthy merchants to bear and share the financial risks involved in this trade, and hence it remained but a marginal solution for the risks implied in long-distance traffic.

A far less controversial means to transfer risks to a third party was through maritime insurance. First introduced in Italy in the fourteenth century, this instrument was regularly used by merchants in Antwerp in the sixteenth century. It was probably in the 1590s that the first policies were written for voyages on the war-ridden trading routes to southern Europe. By 1650 merchants in Amsterdam could take out insurance for shipments to markets around Europe, while smaller markets had emerged in secondary ports such as Middelburg and Rotterdam.

Conclusion

Increasingly poor soil conditions in the late Middle Ages created comparative advantages for peasants in Holland who specialized in dairy farming, shipping, fishing, peat digging, and weaving. This rural stronghold, combined with the proximity of regions with very different opportunity structures, the easy access to the northern seas, and the multitude of navigable rivers and lakes, led to a precocious growth of interior and ocean shipping and domestic and foreign trade after 1400. In the sixteenth century the Dutch economy developed a complementary relationship with that of the southern provinces. Luxury manufactures and capital began to flow to the north, while various foodstuffs, raw materials, and shipping services were sold in the south.

This early interdependence of the two regions is one explanation for the immigration of so many merchants and artisans from Flanders and Brabant in the years following the Dutch Revolt. The subsequent boom in trade, shipping, craft production, and agriculture has led historians to insist on the personal wealth, social networks, commercial and technical skills, or even the capitalist spirit of these immigrants. Besides the numerous Flemish newcomers, and the much smaller group of Portuguese Jews, there was an even larger community of local entrepreneurs who were equally successful in the introduction of new products or the exploration of new markets. Ocean shipping, textile manufacturing, milling, the fisheries, colonial trade, food processing-each of these sectors witnessed important innovations between 1580 and 1650.

More important than the particular skills of a limited number of innovative entrepreneurs was the institutional framework that allowed a much larger number of men (and women) of relatively modest means to set up their own businesses for the marketing of goods and services. On the one hand, towns and villages created commodity markets with the appropriate physical infrastructure, payment system, contracting rules, and a legal system to protect merchants and their goods from violence and opportunism. On the other hand the Dutch Republic boasted efficient factor markets that allowed entrepreneurs to hire laborers, rent land, and obtain capital to invest in their business operations. Commodity and capital markets contributed further by allowing a better management of the risks involved in judgmental decisions about the marketing of goods and services.

The benefits for Dutch entrepreneurs were impressive. From the 1580s onward merchants and manufacturers accumulated large amounts of capital. Colonial trade, commercial farming, urban manufactures, and the exchange of goods within Europe all helped to built large fortunes (Soltow and Van Zanden 1998). Reinvestment of the money earned continued until at least the middle of the seventeenth century. By then, the Dutch Republic boasted a middle class consisting of tens of thousands of self-employed men (and women) who led comfortable lives in the highly urbanized Dutch society (De Vries and Van der Woude 1997, 507–606). A very small group of regents and public officeholders lived more comfortably still, but the large majority of the Dutch population had to make do with only modest wages, or less (Prak 2005, 122–34).

Dutch entrepreneurs did so well in the Golden Age that it seems difficult to explain why the economy lost much of its luster in the late seventeenth and the eighteenth century. The population stopped growing; the pace of technological change slackened; foreign trade and manufacturing stagnated. It has been argued that this is a classical case of entrepreneurial failure.39 The creation of monopolies and cartels increased risk averseness, or even conspicuous consumption may have stifled growth. It is a tempting proposition, given the image of the eighteenth-century Republic as one of regents and renteniers. Few families remained in business for more than three generations, the country's wealth was increasingly concentrated in a few hands; and the most prominent capitalists invested in government bonds and foreign loans rather than business enterprise.

And yet it would be wrong to attribute economic stagnation to entrepreneurial failure. There are several examples of towns adapting the organization of craft production to changing circumstances (Lesger and Noordegraaf 1999b). In Amsterdam commercial and financial innovation continued after 1670. Foreign merchants settled to build up their extensive commission trade, financial entrepreneurs created the first mutual funds and unit trusts, and the largest merchant houses set up as bankers to foreign rulers (Jonker and Sluyterman 2000). Meanwhile, the institutional framework for finance and trade created in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was so efficient that it was copied in surrounding countries. Dutch craftsmen and engineers continued to be sought after by foreign rulers who wanted to improve water management, construction works, and manufacturing in their own territories (Davids 1998). To some extent, the Dutch might be considered victims of their own technological success, for the high quality of the existing infrastructure, transportation system, and energy supplies greatly reduced the expected return from any further improvement (Davids 1995).

If anything, entrepreneurs in the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries displayed a rational attitude toward the political and economic constraints of the time. From the 1670s onward England and France shielded their domestic markets from products from the United Provinces. Investments were redirected and sectors untouched by protectionism continued to have a comparative advantage and consequently remained highly competitive until the late eighteenth century.40 Particularly noteworthy was the strengthening of Amsterdam's economy, with its growing imports from Asia and America, and the financial services it offered to international traders and foreign rulers. The one weak spot exposed by this rebound of the Amsterdam market was the sacrifice of the interests of industrial entrepreneurs in the inland provinces in favor of long-distance trade.41

Appendix: An Estimate of the Number of Entrepreneurs in Amsterdam around 1620

The basic source for the calculation of figures on the number of entrepreneurs in Amsterdam is an official count, instigated by the town magistrate, of the number of active guild members in 1688 (Oldewelt 1942). All but seven guilds responded and reported the size of their membership. To arrive at an estimate for 1620 I calculated the share of these different professional groups in the population of 1680, and then multiplied their relative share by the population of 1622.42 This led to crude estimates for the number of entrepreneurs in manufacturing (2,638), transportation (950), retail trade (1,688), and professional services (i.e., surgeons, notaries, and lawyers, 199).

Obviously, this guild survey only provides us with a rough estimate at best. One of the possible distortions is that entrepreneurs might be a member of more than one guild (Van Tielhof 2002). Furthermore, we merely follow the mainstream view of the massive body of literature on Dutch guilds to argue that, as a rule, the membership of the guilds was limited to the masters, not the journeymen and apprentices (Prak et al. 2006). Although there is evidence to suggest (for example for shipwrights) that some of these masters were employed by others, and worked for wages, it seems reasonable to suggest that the vast majority of guild members were entrepreneurs in the sense that they made judgmental decisions about the employment of labor and capital.

It is fortunate for the present purpose that four of the seven guilds that did not reply to the magistrate's request in 1688 united porters and other handlers of goods—laborers who were the exception to the rule that guilds consisted of entrepreneurs. Of the other three only the Groote Kramers (great retailers) are a problem. For the brokers and lightermen alternative estimates are available. Meanwhile, for various professional groups our estimates are corroborated by other evidence. For example, the total number of mills (including copper-and paper mills, and the like) in Amsterdam in the eighteenth century is estimated at 135, against 94 members of the corn- and timbermillers’ guild in 1688 (Honig 1930).

Finally, a host of primary and secondary sources allows amendment and further refinement of our estimates, as described next:

1. There are two ways to estimate the total number of wholesale traders in Amsterdam. One is to use the number of accountholders in the Exchange Bank in 1620 (1,202) as a proxy (Van Dillen 1925, 2:985). Another is to rely on the very detailed estimate of the number of merchants from the southern Netherlands (400) active in Amsterdam in 1620, and their estimated 30 percent in the city's total merchant community (Gelderblom 2000). This yields a slightly higher estimate of 1,333 merchants. Given that the clientele of the Wisselbank was still expanding at the time (reaching 1,348 accountholders in 1631), I follow the second estimate and set the number of wholesale traders in 1620 at 1,350.

2. Only one important group of retail traders is missing from the guild survey: the Groote Kramers, who specialized in the retail sale of all kinds of textiles. I estimate that their number was similar to that of the Kleine Kramers (about 400), which brings our estimate of the total number of retailers in Amsterdam to 2,600.

3. Transportation. All but two of the major groups of shipmasters in Amsterdam appeared in the guild survey of 1688.

a. The guild of the lightermen, the shipmasters carrying mainly grain from the oceangoing vessels to shore, was asked but did not give information on its membership. However, a by-law issued in 1624 to reduce their number to 225 suggests their number must have been at least 250 in 1620 (Van Tielhof 2002).

b. We also lack information on the number of oceangoing shipmasters residing in Amsterdam in 1620. If we combine the estimated size of the Dutch fleet in the 1630s (1,750) with information on the residence of shipmasters from samples of freight contracts to the Baltic Sea (3 to 6 percent), Norway (0 to 5 percent) and the Iberian Peninsula (17 percent) between 1595 and 1650, a high estimate would be that 150 (i.e., 8.5 percent) shipmasters lived in Amsterdam.43

4. Manufacturing

a. First, I have included entrepreneurs in industries that were not organized in guilds (Van Dillen 1929). I estimate the number of sugar refiners at twenty-five, soap boilers at thirteen to seventeen, and breweries at fifteen to twenty (Poelwijk 2003). To be sure, several of these installations were owned by two or more proprietors, but these were typically merchants, which implies they are already counted with the merchants. Based on the incidence of the professions distilleerder and brandewijnbrander mentioned in contemporary sources (ninety distillers against 125 brewers between 1580 and 1630; these are both workers and bosses), I estimate the number of (brandy) distillers, in keeping with the number of brewers, at fifteen. We also know that in the early seventeenth century the city counted one or two glass producers, a few copper mills, perhaps a salt refinery, and a vinegar boiling house. All in all, an estimate of a total of 150 entrepreneurs, active in unincorporated industries in Amsterdam in 1620, seems reasonable.

b. Diamond cutters are not counted separately, for an analysis of this sector in the period 1590–1610 suggests that in the first decades of the seventeenth century the cutting of stones was largely a putting-out business organized by merchants (Gelderblom 2003b, 2008).

5. The last category, other services, comprises the following professional groups: brokers, hostellers, surgeons, lawyers, and notaries.

a. Oldewelt (1942) mentions 175 as the number of notaries and solicitors in 1688, which, following our estimation strategy would boil down to 84 of them in 1620. This estimate seems reasonable considering the 16 notaries for whom protocols survive in Amsterdam's city archive.

b. Oldewelt (1942) finds 241 surgeons in 1688. I estimate their number at 115 in 1620.

c. The number of brokers in 1618 is known from the membership register of the guild: 438. As for the hostellers, older historians have estimated that the city may have had as many as 500 in the early seventeenth century (Stuart 1879; Visser 1997). This may seem rather high but between 1578 and 1606 alone over 100 hostellers bought the freedom of the city (Amsterdam City Archives, poorterboeken); if we accept that besides inns, Amsterdam also had its fair share of taverns, the 500 seems a number good enough to go by.

The size of the adult population is that of the total population in 1622, adjusted for the share of 15–64 year olds in 1680 (32.8 percent) as estimated by van Leeuwen and Oeppen (1993).

Notes

The author would like to thank William Baumol, Joel Mokyr, Maarten Prak, and Timur Kuran for comments on an earlier version of this chapter and Heleen Kole and Jaco Zuijderduijn for excellent research assistance.

1 The definition of entrepreneurship follows (Casson 2003).

2 Klein 1965. Cf. also Israel 1989; Lesger 2006. Even scholars playing down the contribution of Entrepreneurship implicitly consider a small group of innovative businessmen (De Vries and Van der Woude 1997; Prak 2005).

3 On Flemish immigrants: Gelderblom 2003a, with references to the extensive Dutch literature on the topic. See also Lesger 2006. On the Huguenots: Frijhoff 2003; on the Portuguese Jews: Israel 2002 with references to older studies, including his own.

4 The obvious exception is the vast Dutch-language literature on craft guilds, which has always focused on the artisans in individual workshops (Prak et al. 2006). For a reappraisal of the role of female entrepreneurs in the Dutch Republic, see Van den Heuvel 2007.

5 De Vries and Van der Woude 1997, 61. More detailed case studies of the supply of towns include Lesger 1990 and Boschma-Aarnoudse 2003.

6 The most comprehensive English-language overviews of early modern Dutch entrepreneurship are two edited volumes: Lesger and Noordegraaf 1995, 1999. The older literature is summarized in Klein and Veluwenkamp 1993..

7 Van Zanden 1993; De Vries and Van der Woude 1997; see also the various contributions in Hoppenbrouwers and Van Zanden 2001.

8 De Vries and Van der Woude 1997, 204–5. See Lesger and Noordegraaf 1999, 27–29, and literature cited there on the creation of local commercial infrastructures.

9 The following is based on Boschma-Aarnoudse 2003, 423–26, 453–57.

10De Vries 1974; For a comparative approach: De Vries and Van der Woude 1997, 507–21.

11The best general overview is Bieleman 1992. For a detailed case study of one such area: Van Cruyningen 2000.

12Estimate based on ( a) the low and high population estimates of De Vries and Van der Woude (1997, 50–52) for 1600 (1.4 and 1.6 million) and 1650 (1.85 and 1.9 million); (b) two-thirds of this population aged between fifteen and sixty-five; (c) 40 percent of the population living in towns.

13See, for example, Ehrenberg 1896; Jeannin 1957. Fernand Braudel (1979) explicitly distinguished capitalist entrepreneurs in the major commercial centers of early modern Europe, and self-employed men and women in other areas.

14Recent Dutch studies on the Flemish immigrant entrepreneurs: De Jong 2005; Wijnroks 2003; Gelderblom 2000; Enthoven 1996; on the Portuguese merchants see Vlessing 1995; Lesger 2006; and Israel 1990.

15The histories of Lemaire and Van Os are recounted in Gelderblom 2000. See also Van Dillen 1930.

16The first voyages of Tweenhuysen are detailed in Hart 1957. See also the even older Muller 1874.

17On beer: Yntema 1992, Unger 2001. On dairy production: Boekel 1929; Van Bavel and Gelderblom 2010.

18On brickworks: Kloot-Meyburg 1925; on madder: Priester 1998, 324–65; on salt refining: Van Dam 2006.

19My interpretation of technological change builds on Davids 1995. See also Davids 2008.

20On the exploration of new markets: Israel 1989; on bookkeeping: Davinds 2004.

21On sugar refiners see, for example, Poelwijk 2003; on leather production, Gelderblom 2003b; on tobacco manufacturing, Roessingh 1976.

22The example is based on Gelderblom 2003b.

23Davids 1995; On glass manufacturers: Mentink 1981; for silk: Colenbrander 1992.

24The greater efficiency that could be achieved with such measures, provided the government carefully weighed opposing economic interests, has been argued by Lesger 1999, 33–35, 39–40.

25Meilink 1922. In 1542 the Habsburg rulers demanded a 10 percent levy on the profits from trade. After fierce protests the levy was replaced by a tax on a fictional 6 percent return on the capital of merchants, shipmasters, herring fishers, and exporting beer brewers.

26The following is based on Gelderblom, forthcoming.

27The following is based on Gelderblom and Jonker 2004.

28For the guarantor to be credible required him to pledge his own person and goods as surety. Since he did not have to do anything but assert this pledge, only merchants whose wealth was relatively well-known to the other party would be accepted as surety. This reliance on familiarity would make it more problematic for itinerant merchants, hence presumably the initial rule—implicit in the privileges of the German Hansa—that any group member could be held responsible.

29Maassen 2005. Pawning had been a common procedure in the Low Countries since at least the twelfth century: Godding 1987, 256–57.

30As a result the only commodities widely used as collateral for loans other than postponed payments were jewelry, gold and silver plate, and precious stones. In Amsterdam, notarial deeds testify to the use of precious stones and jewelry as collateral: In 1627 the Amsterdam merchant “nam tot zich” jewels and paintings to compensate for an obligation of 1,029 guilders (including interest) that had not been repaid (GAA NA Card Index, NA 392/82, August 2, 1627). In 1630 an Amsterdam merchant held a jewel to secure money lent by him to a fellow merchant (GAA NA Card Index, NA 847/141, April 6, 1630); for other examples: NA 646b 1035–36 (October 22, 1624); NA 700 A 235–37 (June 21, 1625); NA 307/blz. 196–97 (November 26, 1632); NA 642/344 (February 24, 1637); NA 676/68–69 (September 24, 637).

31For the introduction of these rules in the late medieval period: Zuijderduijn 2009. In 1622 the Dutch Republic required the registration, by the local court, or a notary—in the case of Amsterdam—of transfers of ships of four lasts (eight tons) and bigger in case of sale or pledging as collateral. Dutch customary law did not allow creditors of loans with ships as collateral to repossess the ship to get their money back (Lichtenauer 1934, 53–56).

32Hugo Soly (1977, 81) was the first to draw attention to the use of annuities for the funding of small businessmen. His analysis of the sellers of these renten in Antwerp in 1545 and 1555 bears out the importance of the instrument for merchants, cloth finishers, masons, carpenters, and various other artisans.

33For a detailed analysis of loans by goldsmiths: Gelderblom 2008.

34Following the rules set by Charles V in the 1540s, creditors who wanted to liquidate a claim prematurely could do so by selling the obligation to a third party.

35The following is based on Gelderblom and Jonker 2004.

36See Hoffman et al. 2000 for the role of notaries in Parisian credit markets after 1660.

37One could also argue that the success of Dutch entrepreneurs in the Golden Age resulted from their great willingness to take these risks. This is one of two arguments Roessingh put forward to explain the willingness of Dutch peasants to grow tobacco plants for the national and international market in the seventeenth century (Roessingh 1976, 278–79). However, he does not provide solid evidence for this thesis.

38The point is further developed in Gelderblom, forthcoming.

39For a historiography of the debate on entrepreneurial failure: Lucassen 1991.

40For new initiatives in tobacco manufacturing: Roessingh 1976, 408–24; Verduijn 1998; Mayer-Hirsch 1999. For a successful start-up, see, for example, the Utrecht wine seller Barend Blomsaet, who started his career with a few hundred guilders, a capital that grew within two decades to 15,000 guilders (Tigelaar 1998, 23–24).

41Lesger and Noordegraaf's (1999) interpretation: urban and provincial particularism (a medieval legacy) brought Holland on top of the rest of the Republic. It fostered its growth but damaged the economic interests of other provinces.

42Town population from Lourens and Lucassen 1997.

43Jonker and Sluyterman 2000; Knoppers 1977; Winkelman 1983; Schreiner 1933; Christensen 1941, 264–65.

References

Baars, C. 1975. “Boekhoudingen van landbouwbedrijven in de Hoeksewaard uit de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw.” A.A.G. Bijdragen 19:3–136.

Bieleman, Jan. 1992. Geschiedenis van de landbouw in Nederland, 1500–1950: Veranderingen en verscheidenheid. Meppel: Boom.

Boekel, Pieter N. 1929. De zuivelexport van Nederland tot 1813. Utrecht: Drukkerij Fa. Schotanus & Jens.

Bonke, A.J.J.M., W. Dobber, et al. 2002. Cornelis Corneliszoon van Uitgeest: Uitvinder aan de basis van de Gouden Eeuw. Zutphen: Walburg Pers.

Boot, J. A. 1974. “De markt voor Twents-Achterhoekse weefsels in de tweede helft van de 18de eeuw.” Textielhistorische Bijdragen Jaarverslag 16:21–68.

Boschma-Aarnoudse, C. 2003. Tot verbeteringe van de neeringe deser stede. Hilversum: Verloren.

Braudel, Fernand. 1979. Civilisation Matérielle, économie et capitalisme, XVe-XVIIIe siècles. Paris: Colin.

Broeze, F.J.A. 1976–78. “Rederij.” In Maritieme geschiedenis der Nederlanden, ed. F.J.A. Broeze, J. R. Bruijn, and F. S. Gaastra, vol. 3. Bussum: Unieboek.

Bruijn, Jaap R. 1993. The Dutch Navy of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Brünner, Eduard C. G. 1924. “Een Hoornsch koopmansboek uit de tweede helft der 15e eeuw.” Economisch-Historisch Jaarboek 10:3–79.

Brusse, Paul. 1999. Overleven door ondernemen: De agrarische geschiedenis van de Over-Betuwe 1650–1850. Wageningen: Afdeling Agrarische Geschiedenis Landbouwuniversiteit.

Casson, Mark C. 2003. “Entrepreneurship.” In Oxford Encyclopaedia of Economic History, ed. Joel Mokyr, 2:210–15. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Christensen, Aksel E. 1941. Dutch Trade to the Baltic about 1600: Studies in the Sound Toll Register and Dutch Shipping Records. Copenhagen: E. Munksgaard.

Colenbrander, S. 1992. “Zolang de weefkonst bloeijt in ‘t machtig Amsterdam. Zijdelakenfabrikeurs in Amsterdam in de 17de en 18de eeuw.” Textielhistorische Bijdragen Jaarverslag 32:27–44.

Davids, Karel. 1995. “Beginning Entrepreneurs and Municipal Governments in Holland at the Time of the Republic.” In Entrepreneurs and Entrepreneurship in Early Modern Times: Merchants and Industrialists within the Orbit of the Dutch Staple Market, ed. Clé M. Lesger and Leo Noordegraaf, 167–83. The Hague: Stichting Hollandse Historische Reeks.

——. 1995. “Shifts of Technological Leadership in Early Modern Europe.” In A Miracle Mirrored: The Dutch Republic in European Perspective, ed. K. Davids and J. Lucassen, 338–66. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——. 1998. “Successful and Failed Transitions: A Comparison of Innovations in Windmill

Technology in Britain and the Netherlands in the Early Modern Period.” History and Technology 14:225–47.

——. 2004. “The Bookkeeper's Tale: Learning Merchant Skills in the Northern Netherlands in the Sixteenth Century.” In Education and Learning in the Netherlands, 1400–1600: Essays in Honour of Hilde de Ridder-Symoens, ed. K. Goudriaan, J. v. Moolenbroek, and A. Tervoort, 235–51. Leiden: Brill.

——. 2008. The Rise and Decline of Dutch Technological Leadership. Technology, Economy and Culture in the Netherlands, 1350–1800. 2 vols. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Den Heijer, H. J. 2005. De geoctrooieerde compagnie: De VOC en de WIC als voorlopers van de naamloze vennootschap. Deventer: Kluwer.

De Vries, Jan. 1974. The Dutch Rural Economy in the Golden Age, 1500–1700. New Haven: Yale University Press.

De Vries, Jan, and Ad Van der Woude. 1997. The First Modern Economy: Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dekker, Rudolf. 1982. Holland in beroering. Oproeren in de 17de en de 18de eeuw. Baarn.

Doorman, G. i. 1956. “Het haringkaken en Willem Beukels.” Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 69:371–86.

Eeghen, I.H.v. 1961. “Buitenlandse monopolies voor de Amsterdamse kooplieden in de tweede helft der zeventiende eeuw.” Jaarboek van het Genootschap Amstelodamum 53:176–84.

Eerenbeemt, H.F.J.M van den. 1983. “Zijdeteelt in Nederland in de 17e en eerste helft 18e eeuw.” Nederlands Economisch Historisch Archief—Jaarboek 46:142–53.

——. 1985. “Zijdeteelt in de tweede helft van de 18e eeuw.” Nederlands Economisch Historisch Archief—Jaarboek 48:130–49.

——. 1993. Op zoek naar het zachte goud. Pogingen tot innovatie via een zijdeteelt in Nederland 17e-20e eeuw. Tilburg: Gianotten.

Ehrenberg, Richard. 1896. Das Zeitalter der Fugger, Geldkapital und Creditverkehr im 16. Jahrhundert. Vol. 2, Die Weltbörsen und Finanzkrisen des 16. Jahrhunderts. Jena: Fischer.

Enthoven, Victor. 1996. “Zeeland en de opkomst van de Republiek. Handel en strijd in de Scheldedelta c. 1550–1621.” Ph.D. diss., Rijksuniversiteit Leiden.

Frijhoff, Willem. 2003. “Uncertain Brotherhood: The Huguenots in the Dutch Republic.” In Memory and Identity: The Huguenots in France and the Atlantic Diaspora, ed. Bertrand Van Ruymbeke and Randy J. Sparks, 128–71. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Gelderblom, Oscar. 2000. Zuid-Nederlandse kooplieden en de opkomst van de Amsterdamse stapelmarkt (1578–1630). Hilversum: Verloren.

——. 2003a. “From Antwerp to Amsterdam: The Contribution of Merchants from the Southern Netherlands to the Commercial Expansion of Amsterdam (c. 1540–1609).” Review: A Journal of the Fernand Braudel Center 26, no. 3: 247–83.

——. 2003b. “The Governance of Early Modern Trade: The Case of Hans Thijs (1556–1611).” Enterprise and Society 4:606–39.

——. 2005. “The Resolution of Commercial Conflicts in Bruges, Antwerp, and Amsterdam, 1250–1650.” http://www.lowcountries.nl/2005–2_gelderblom.pdf.

——. 2008. “Het juweliersbedrijf in de Lage Landen,” unpublished working paper Utrecht University.

——. Forthcoming. Violence, Opportunism, and the Growth of Long-Distance Trade in the Low Countries (1250–1650).

Gelderblom, Oscar, and Joost Jonker. 2004. “Completing a Financial Revolution: The Finance of the Dutch East India Trade and the Rise of the Amsterdam Capital Market, 1595–1612.” Journal of Economic History 64, no. 3: 641–72.

——. 2005. “Amsterdam as the Cradle of Modern Futures Trading and Options Trading, 1550–1650.” In The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations That Created Modern Capital Markets, ed. William N. Goetzmann and K. Geert Rouwenhorst, 189–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Godding, Philippe. 1987. Le droit privé dans les Pays-Bas méridionaux, du 12e au 18e siècle. Brussels: Académie royale de Belgique.

Greefs, Hilde, and Marjolein ‘t Hart, eds. 2006. Water Management, Communities, and Environment: The Low Countries in Comparative Perspective, c. 1000—c. 1800. Hilversum: Verloren.

Guicciardini, L., G. Silvius, et al. 1567. Descrittione di M. Lodouico Guicciardini patritio Fiorentino, di tutti i Paesi Bassi, altrimenti detti Germania inferiore: Con piu carte di geographia del paese, & col ritratto naturale di piu terre principali. In Anuersa: Apresso Guglielmo Siluio stampatore regio.

Hacquebord, L. 1994. “Van Noordse Compagnie tot Maatschappij voor de Walvisvaart. Honderd jaar onderzoek naar de geschiedenis van de Nederlandse walvisvaart.” Tijdschrift voor Zeegeschiedenis 13:19–40.

Hart, Simon. 1957. “De eerste Nederlandse tochten ter walvisvaart.” Jaarboek van het Genootschap Amstelodamum 49:27–64.

Hoffman, Philip T., Gilles Postel-Vinay, and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal. 2000. Priceless Markets: The Political Economy of Credit in Paris, 1660–1870. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Honig, Gerrit J. 1930. “De Molens van Amsterdam (De invloed van de molens op het Indus-trieele leven in de Gouden Eeuw).” Amstelodamum. Jaarboek van het genootschap Amste-lodamum 27:79–159.

Hoppenbrouwers, Peter C. M., and Jan Luiten Van Zanden, eds. 2001. Peasants into Farmers? The Transformation of Rural Economy and Society in the Low Countries (Middle Ages-19 th Century) in Light of the Brenner Debate. CORN Publication Series 4. Turnhout: Brepols.

Israel, Jonathan I. 1989. Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585–1740. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press.