CHAPTER ONE

The Shipbuilders’ War

THE WAR OF 1812 MAY BE THE LEAST REMEMBERED OF AMERICAN WARS. And buried in the historical fog is the strange tale of a naval arms race on Lake Ontario. Ontario is the smallest of the Great Lakes and virtually landlocked. Yet in the early winter of 1815, twenty formidable warships were scheduled to take to the water at the spring thaw. Four of them would be first-raters, two of them American, two of them British, each of them ranking among the largest and most heavily armed warships in the world.

Great Britain was the world’s greatest-ever naval power. Of the 600 or so war vessels in the Admiralty’s active fleet, about 110 were ships of the line, all big, powerful vessels designed to overawe and overwhelm the enemy. Of the in-service ships of the line, however, only six were first-raters. They were one of the age’s most complex machines, the behemoths of the ocean, two hundred feet long, displacing 2,500 tons, top masts soaring two hundred feet above waterline, carrying crews of eight hundred seamen and marines and disposing of at least 100 heavy guns in three tiers along their sides. Building a first-rater consumed 4,000 large trees; hundreds of tons of iron for fittings, cannon, and ballast; miles of rigging; an acre and a half of sail; some 1,400 ship pulley-blocks, some of them almost as tall as a man. Nelson at Trafalgar led the charge against the Napoleonic armada in his first-rater, HMS

Victory.

1During the first year of the war, it became clear to both sides that winning control of Lake Ontario was the key to winning the war, and both poured money and resources into the effort. Both sides expected that an early naval battle would decide the issue, but inherent asymmetries in armaments and naval tactics trapped them both within the grim logic of an escalating arms race. To the surprise of both participants, the Americans doggedly matched and raised the British step by step, until both were at the point of exhaustion.

A War of Honor

The American declaration of war against Great Britain in June 1812 is a puzzlement for historians. The death struggle between the British and Napoleonic France indiscriminately inflicted damage on neutral countries. If anything, the French were the more disdainful of Americans and worked the greater destruction on American shipping. As Henry Adams pointed out, every charge in President Madison’s war declaration was both factually correct and a sufficient cause for war. But the United States had patiently endured such behavior for five years, so why declare war in 1812, when the American government was close to insolvency and Great Britain was on the brink of making major trade concessions?

2British and Canadian historians tend to see the war as an unsuccessful American war of conquest.

a Congressional war hawks, in fact, made no secret of their desire to annex parts of Canada, but they did not come close to commanding a legislative majority. Public outrage was more focused on the British impressment of American merchant seamen. In principle, the British had a right to take their own nationals, but naval captains were not overly scrupulous about trapping bona fide American citizens in their trawls. The Royal Navy was their Maginot Line against Napoleon, and years of warfare had created a terrible shortage of seamen. Even American officials privately acknowledged that up to a quarter of US merchant seamen were deserted British nationals, and citizenship papers for British seamen were sold openly in most American ports.

3Behind the headline issues, the old characterization of the war as the second war for American independence has considerable truth. The British still reflexively treated America as a component of its colonial/mercantile empire, high-handedly issuing detailed trade licenses while refusing a generalized trade treaty. Royal Navy captains felt free to sail into American ports and haughtily, and occasionally forcefully, sequester scarce provisions. The London

Times sneered in 1807 that Americans could not “cross to Staten Island” without the Royal Navy’s permission.

4But national pride couldn’t dispel the reality that the United States was in no shape to fight a war. Years of British and French blockades had devastated customs revenues. Its navy consisted of some coastal gunboats and a handful of frigates, all built in the 1790s. The army was small and scattered through frontier outposts, so the primary ground forces were state militias, which were inconsistently trained and armed, if at all, and often prevented by law from serving outside their home states. Governors in several federalist states, moreover, announced that they would not release their militias for federal service on constitutional grounds.

5 Few senior officials had significant recent military experience.

The war proceeded on several loosely connected fronts. In the first year of the war, the most spectacular encounters were a series of frigate-to-frigate ocean battles.

b The

Constitution’s half-hour destruction of the British

Guerrière prompted unrestrained celebration in America and shocked laments in London. The Royal Navy finally put an end to such impertinences by imposing a suffocating blockade up and down the coast that kept the frigates almost entirely port-bound for the duration of the war.

With the blockade in place, sea action shifted to an intense informal war between the Royal Navy and American privateers, especially the famous Chesapeake Schooners, or Baltimore Clippers. They were the leopards of the sea: up to a hundred feet long, mounting up to 18 guns, with vast expanses of sail, deep keels for rapid maneuverability, and superb hydrodynamics. They consistently outsailed and outwitted British warships, and by the later stages of the war, even prowled in the Thames.

6 In addition, throughout the war years Andrew Jackson led a sporadic Indian war in the Southeast, an early salvo in a two-decade-long ethnic-cleansing operation. He and other local commanders raised and equipped their troops and operated more or less independently of Washington.

The most important fighting, however, whether measured by casualties, commitment of resources, or persistence, was centered on the lakes, especially Ontario and Erie, reinforcing the contention that the war was about Canada, for whoever controlled the lakes would inevitably control Canada.

The Lake Arena: Early Stumbles

The British had only the lightest of colonial presences in Canada. There was a world-class Royal Navy port at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and just to the west the territory of Lower Canada, predominately French, included substantial commercial centers at Quebec and Montreal. Upper Canada stretched along the lakeshores: it was primitive and Anglophone, probably mostly settled by Americans who had straggled across the border. Both Upper and Lower Canada were under the direction of Governor-General George Prevost, an experienced British general officer based in Quebec.

The only practical access to Upper Canada was via the St. Lawrence. The river was navigable by ship as far as Montreal; from there, the 150-mile stretch to Lake Ontario was dominated by rapids and shallows traversed by towed bateaux and barges. The territory was barely self-sufficient in food, with few roads and little in the way of industry, so a defense force would be completely dependent on river-borne supplies. Losing control of the St. Lawrence or of Lake Ontario virtually guaranteed the loss of Upper Canada and could put much of Lower Canada at risk.

The demographics of the lakes clearly favored the Americans, whose lakeshores were more populous, with better internal transportation, highly productive farmland, and budding iron industries that could support the war effort. But the British compensated by fashioning broad alliances with Indian tribes seeking to stop American settlement. Western settlers were in terror of the Indians, especially after the success of the great Indian leader Tecumseh in cobbling together a serious Indian confederacy. The battle with Tecumseh’s forces at Tippecanoe, in November 1811, was officially celebrated as an American triumph, but cognoscenti knew it was a close-run thing, with Americans taking the heavier casualties. Even militias panicked and ran from Indian detachments in the early stages of the war.

The Americans took the early military initiatives in the summer of 1812, almost all on the ground, producing pratfalling, Marx Brothers–class fiascos, too costly and bloody to be comic. General William Hull made a timorous thrust up the Detroit River and surrendered to a much smaller force at almost the first shots, giving up his army, Ft. Detroit, a warship, and the entire Michigan territory. Henry Dearborn, another aging Revolutionary War general, launched a large, lethargic, but complex nighttime attack in the Niagara peninsula. Amid indiscipline and chaos, his ill-prepared troops took very heavy casualties. Dearborn later tried a second action directed at Montreal but retired to winter quarters after a brief skirmish near Plattsburgh. A wag called it a failure “without even the heroism of a disaster.”

7If nothing else, the early failures demonstrated that naval control of the lakes was crucial for effective movement of troops and supplies. The Americans were the first to respond, naming Isaac Chauncey to a new post of naval commander of the lakes. Chauncey was an experienced, active, officer and, fortuitously, had most recently been commander of the New York Navy Yard. It took until the following spring for London to realize that Chauncey’s vigor was putting Canada at risk. They responded in March 1813 by appointing Sir James Lucas Yeo to lead a naval expeditionary force to the lakes. Only thirty years old, Yeo was already a post-captain, with a long record as a fighting officer, and possessed by the same drive and force of personality as Chauncey. When Yeo arrived at Lake Ontario in May 1813, the shipbuilders’ war was on.

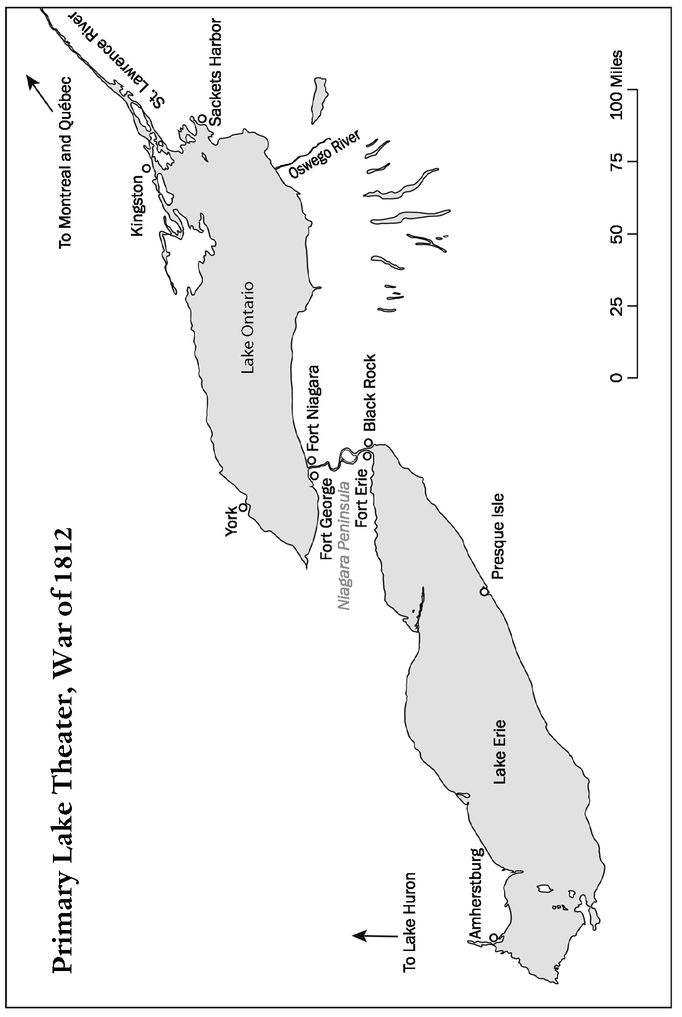

Primary Lake Theater, War of 1812

Industrial War in the Wilderness

The shipbuilders’ war lasted for two and a half years. Both sides constructed substantial cities at their primary bases near the mouth of the St. Lawrence. The British base at Kingston, on the north shore, was a thirty-mile sail from the American base on the opposite shore, at Sackets Harbor. By war’s end, each was able to house and feed some 5,000 semipermanent residents—seamen, marines, and their officers; shipwrights, smiths, and other craftsmen—plus massive ship factories and associated shops, as well as facilities for short-term feeding and support of the thousands of infantrymen mustered from time to time for amphibious operations.

It was easy to underestimate the challenges of the lakes—on maps they looked like mere puddles. But winds were highly variable, and violent storms sprang up almost without warning. (Shallow waters often generate the most violent storms; ocean depths absorb the force of surface disturbances.) The lakes’ heavy fogs and frequent squalls, and the near-constant presence of a lee shore, jangled captains’ nerves. On Lake Huron, an American captain found himself “embayed in a gale of Wind on a rocky Ironbound shore . . . shipping such immense quantities of water as to give me very serious alarm for some hours.” The whole coast, he said, was “a steep perpendicular Rock” and navigation “extremely dangerous . . . falling suddenly from no soundings into 3 fathoms [18 feet] & twice into ¼ less twain [10½ feet].”

8The challenge was to build “weatherly” fighting ships fast and cheaply—cutting corners without compromising performance. Ships built of unseasoned wood go to rot within just a few years, so many finishing details could be dispensed with. With no need to carry water or long-term supplies, they had smaller holds and shallower drafts, enabling close approaches to shore. The American ships especially carried large expanses of sail and heavy gunnery for their size. For example, to the British the American Pike was a difficult sailer, but in the hands of an expert crew, it was among the quickest and most maneuverable warships on the lakes.

Chauncey’s orders were the kind commanders dream of. He was “to obtain control of the Lakes Ontario & Erie, with the least possible delay.... With respect to the means to be employed, you will consider yourself unrestrained [and] . . . at liberty to

purchase,

hire or

build, such [vessels] . . . of such form & armament” as he chose.

9His prize acquisition was Henry Eckford, one of the age’s great naval architects and owner of a private shipyard in New York. He turned out to be a master of improvisation—as in devising easier-to-build bracings for ships with short shelf lives. Old hands expected Eckford’s ships to break in two when they were launched down the slipway, but all of them performed well. Backing up Eckford were the Brown brothers, Noah and Adam, who also operated a New York boatyard. The Browns designed and built the ships on Lakes Erie and Champlain, and worked so smoothly with Eckford on Ontario that scholars have difficulty in distinguishing their work from his.

The British building program was supervised mostly by William Bell, a Canadian who had run a boatyard on Lake Erie, and later by Thomas Kendrick, an experienced naval architect from London. A senior British officer, Capt. Richard O’Conor, was assigned full-time to manage the yards. Both sides achieved rapid construction schedules, although fully masted ships often sat at shipyard docks for weeks or months waiting for critical components, like cannon or ship’s cable.

Chauncey was also something of a gadgeteer. His fleet usually had between a dozen to sixteen of its long guns on swivels, so they could be deployed on either broadside. He also experimented with rapid-fire weapons, known as Chambers guns, after their Philadelphia inventor. A British spy described them as having: “seven barrels . . . throw[ing] 250 balls at each fire . . . [with] one Lock & the fire is communicated fm. Barrel to Barrel—& they discharge successively at the Interval of one Second.”

10Wars turn on logistics. In the shipbuilders’ war both sides had endless supplies of timber for the taking but had to import virtually all tools and nonwooden materials, like rope, ordnance, iron fittings, and shot. The Americans had decent river and canal transport from New York City to the port of Oswego on Lake Ontario, although it required some portages. For Lake Erie there was inland ground transport from Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, but in that era, almost all roads were execrable most of the time. An artillery major bringing cannon from Pittsburgh in the early winter of 1813 wrote of days at a stretch when they were “with our horses to their middles in mud and water.”

11 Even in the dry summer of 1812, Chauncey lost whole cannons when wagons overturned in a mire.

The Chambers Gun was a fusillade weapon, firing a hail of cylindrical slugs. Ignition was by single flintlock in front, and was communicated from barrel to barrel through touch holes and a roman-candle-type fuse. The firing spark also traveled backward through the slugs by fuses that ignited powder packed throughout the column. The guns were said to be rapidly loaded. It is possible that the slugs, powder, and fuses were prepacked in copper tubes that could be loaded and extracted rather like modern ammunition clips.

For the British, it was actually an advantage to source supplies from England, since ship transport from Portsmouth to Montreal was fast and reliable, while bateaux transport to Lake Ontario took only a few days. The problem was getting from the lake entrance to the British base at Kingston. When the lake was under American control, a war schooner or two sitting at the mouth of the St. Lawrence stopped the British supply train cold. In periods when the lake was contested, the trip required military escort, and jam-ups of cargo bateaux awaiting escort could stretch for miles. Overland transport was a poor option: some supplies could get through, but not enough to sustain a burgeoning military presence. British food requirements were magnified by the Indian alliances, for the tribes quickly learned the advantages of takeout service from the British mess. One commander wrote in alarm to headquarters in 1813, “The quantity of Beef and flour consumed here is tremendous, there are such hordes of Indians with their

wives and

children.”

12

Chauncey Rules Ontario: October 1812 to May 1813

Within weeks of his appointment, Chauncey started a massive caravan of shipwrights, mechanics, sailors, marines, ordnance, and supplies on the road to Sackets Harbor. Eckford went with the earliest groups to start laying out construction plans. Militarily, they were starting almost from scratch (see

Table 1.1).

13By mid-November, Chauncey and Eckford had built a naval yard and dry dock and facilities for 1,000 men and officers. The Madison, a graceful, new 24-gun corvette, or subfrigate, was launched on November 26, just forty-five days from starting its keel. By that time, Chauncey had also bought up a number of lakers, local transport workhorses. He netted several modest schooners, which were slow but could carry up to 10 guns, and some smaller gunboats with both sails and rowing stations. Outfitted with 1 or 2 long guns, the gunboats could pose a real threat to shoreside troops or to a becalmed warship. Also in May, a daring long boat raid on Lake Erie, led by Lt. Jesse Elliott, cut out and burnt the Detroit and captured a gunboat, the Caledonia.

TABLE 1.1 Naval Forces on the Lakes: September 1812

Even better, once Chauncey took the

Oneida out on the lake, he discovered that the Provincial Marine, which was trained as a security service, didn’t fight. He began to attack British shipping at every opportunity, taking several prizes, and at one point chased the

Royal George all the way into Kingston. Even without the

Madison, he could truthfully report that he had “command of the Lake” and could transport troops and stores anywhere “without any risk of an attack by the Enemy.”

14The lakes were icebound in winter, which facilitated troop movements and led to more American disasters. An American offensive in the Detroit area ended with a large detachment being “cut to pieces.”

15 American prisoners were later massacred by a party of Indians near the River Raisin: “Remember the Raisin” became an American rallying cry. The British cemented their control of the St. Lawrence by capturing the town of Ogdensburg. The Americans fended off an attack at Ft. Meigs, on the Detroit River, but lost almost all of an American relief force, some of whom were also massacred by Indians.

In Washington, there was a shake-up in the military departments. John Armstrong, a former senator and ambassador with presidential ambitions and a reputation as a strategist, took over the war department. He proved to be an intriguer and a windbag with an unparalleled gift for sowing confusion. The new naval secretary, William Jones, was a former shipwright who had risen to head a large merchant house. His dispatches were informed, crisp, and intelligent. As the tightening British coastal blockade kept the Atlantic fleet locked in port, he started transferring their crews to the lakes—among them a fast-rising young naval captain, Oliver Hazard Perry, who joined Chauncey with 150 men and was given command of Lake Erie, with Lt. Elliott as his second.

Chauncey was back on Lake Ontario with the first thaw. In late April he coordinated an attack on York, the provincial capital (and present-day Toronto), where the British were constructing a major new warship. Chauncey took his whole fleet: the Madison, the Oneida, and eleven lakers, wallowing with the weight of 1,700 ground troops.

York was defended by British regulars, but the beach assault came off briskly, as the warships silenced York’s artillery. Within a couple of hours, the British were in retreat, the new warship was burnt, the Duke of Gloucester taken, and large amounts of stores captured, all with light casualties. An easy victory turned to disaster when an arms magazine that had been mined by the retreating British blew up next to the main American infantry group. Gen. Zebulon Pike, the American infantry commander, and another 38 soldiers were killed, with 221 wounded. Technically, the action met its objectives, but the butcher’s bill—320 casualties in all—was grossly disproportionate.

A month later, Chauncey took the fleet to Niagara for an attack on Britain’s Ft. George. A 4,000-man army, with promising new second-rank commanders like Winfield Scott, was assembled and waiting for naval support. Once again, the beach assault went like clockwork, as warships poured grapeshot into the defenders and pounded their artillery emplacements. By ten AM, with the fort in flames and the Madison disgorging yet more fresh troops, the British commander sounded a withdrawal. The army then quickly rolled up the rest of the peninsula, including the British outpost at Ft. Erie. Both expeditions were striking demonstrations of the potential of combined-arms operations on the lakes.

Countermove

Shortly before Chauncey mounted his Niagara campaign, Commodore Yeo had arrived at Kingston, with a cadre of 465 officers and seamen. He was met by Governor-General Prevost, his local superior, and Roger Sheaffe, the military commander for Upper Canada who had marched his troops there after the bloodying at York. The three were holding war councils when a huge plume of black smoke from the west announced the siege of Ft. George. With the whole American fleet up-lake, they decided to mount a surprise attack on Sackets Harbor. On May 26, the British dispatched an 800-strong assault force, including all four of Yeo’s warships and a half dozen gunboats, towing a flotilla of landing craft—thirty-three boats in all.

Tactically, the assault was a failure. A first attempt was interrupted by a sudden storm, so the Americans had an extra day to organize their defense. When the British made the beach the next day, they took heavy fire. Casualties would have been much worse if a seven-hundred-strong contingent of state militiamen, carefully positioned in ambush, had not broken and run at the first shots. Then a young American lieutenant mistakenly fired Sackets’s stores and a nearly finished new warship. By that time, the assault force’s casualties exceeded a quarter of its men. The British commander chose to assume that the smoke signaled destruction of the warship and sounded the withdrawal. In fact, the ship was only scorched, and the burnt stores were replaced within a few weeks. Strategically, however, the raid radically changed the calculus of power. From that point, Chauncey was almost paranoid about Sackets’s defenses and sharply curtailed his participation in joint land-sea operations.

TABLE 1.2 Naval Forces, Lake Ontario: August 1813

In the meantime, the construction race moved into higher gear. The British had launched the

Wolfe, a 22-gun corvette, in April, followed by the launch of a war schooner, the

Lord Melville (16), in July. Chauncey countered with the

General Zebulon Pike, the ship that was scorched during the Sackets raid. It may have been Eckford’s masterpiece, a beautiful 26-gun corvette, the fastest and most powerful warship on the lake. The

Pike was followed in August by a new war schooner, the

Sylph (18), together with a very fast single-gun courier sloop,

Lady of the Lake.

Table 1.2 shows the state of the standoff on Ontario as of about mid-August.

With such an investment, both national capitals expected a climactic early battle to settle the war. It never happened—because inherent asymmetries in the fleets and their tactics made it almost impossible for the two commanders to agree to fight.

To begin with, the favored Royal Navy ordnance were carronades: stubby, relatively inaccurate guns with heavy payloads that were easy to reload. Nelson’s doctrine was “no captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of the enemy.”

16 The standard British tactic—bloody but fearsome and effective—was to close rapidly, pound away hull to hull, then grapple and board. Most ships mounted just a few long-range guns, and few captains even practiced long gunnery.

The Americans had a much higher ratio of long guns—Chauncey insisted on it. He drilled in gunnery, and his crews were decent artillerists. As

Table 1.2 shows, the throw weight of metal

c for the two fleets was the same—about 2,700 pounds—but more than 40 percent of the American throw weight was in long guns, compared to a peashooter’s worth for the British. In a fight, the American long-range advantage was even higher, since 15 of their long guns were on swivels and could fight on either side, while the British had only 1 small swivel gun. The advantage shifted to the British in hull-to-hull battles: nominal throw weights were the same, but carronades used smaller crews and had faster firing cycles.

Sailing characteristics reinforced the asymmetry. Eckford’s ships the

Madison, the

Pike, and the

Sylph were superb, but the

Oneida was “a perfect slug,”

17 and the rest, all converted lakers, were notoriously clumsy sailers, so Chauncey had serious problems keeping his squadron together. The Royal Navy, by contrast, placed a high premium on convoy sailing, and it was a constant focus of their drills. Chauncey and his officers marveled at Yeo’s tight-formation fleet maneuvers: “all sailing alike and able to support each other in any weather.”

18Yeo would therefore naturally choose to engage the Americans on a day of tricky winds and choppy waters. The weather would scatter the American fleet and degrade its long-range gunnery, while superior British convoy sailing would allow them to swarm their targets. Chauncey’s preferred scenario was precisely the opposite. With calm waters, he could stand off beyond carronade range, pound away at British rigging and gunports, and then close against wounded targets. In other words, with roughly equal forces, the two commanders would almost never choose to fight at the same time.

The obvious way to break the impasse was to acquire such overwhelming force that the asymmetries ceased to matter. But that would provoke the weaker opponent to avoid a fight at all costs, while redoubling his building efforts. In short, the Ontario shipbuilders’ war was a classic arms race, like the Soviet-American missile race, that would continue until one side or the other was exhausted. All the professionals on the lake understood this and frequently commented on it, even as Chauncey and Yeo, in their dispatches to headquarters, lamented in almost identical tones the unwillingness of the other to engage in a climactic battle.

Some Not-So-Close Encounters: Ontario, Summer–Fall 1813

Yeo’s temporary dominance of the lake ended on July 22, when Chauncey, leading his fleet in the Pike, mounted another raid on York, then dropped down to Niagara and sent off one hundred experienced seamen to man Perry’s Erie squadron. A week later, with the Melville entering service, Yeo felt strong enough to go out and hunt for Chauncey. On the morning of August 7, the two fleets sighted each near the mouth of the Niagara River, and both announced their intent to fight by firing cannons.

The two fleets proceeded on a tack to meet just west of the river. Yeo was in the Wolfe, with all five of his other warships. Chauncey was in the Pike, with the Madison and the Oneida and nine of his lakers. The British stayed in tight formation, but the American fleet quickly broke into three clusters. Chauncey reversed his course to gather up the fleet. Yeo turned as well but headed in the opposite direction. Watchers on the shore expecting to see the long-awaited showdown could not believe their eyes.

Yeo was just being sensible. By reversing course to await his lakers, Chauncey signaled his intent to open the battle at long range—the lakers had a third of his long guns. The water was calm, ideal for American gunnery, and Yeo had no interest in playing target-practice dummy.

19That night, the British lay near York, while Chauncey was still far across the lake. A sudden, and violent, electrical storm capsized the two largest lakers, the Hamilton and Scourge, with the loss between them of some eighty men and 19 guns. After a service for the drowned men, Chauncey brought his fleet to within firing range of Yeo. As they were on the point of engaging, a nasty squall sprang up, and both sides broke off. Chauncey decided that from then on his newer warships would tow the lakers to the point of an engagement.

Finally, the fourth day of the encounter, August 10, appeared to offer a real fight. Yeo’s fleet, caught in a calm, was spotted by the Americans, who were about twenty miles away with a good breeze. Chauncey poured on the sail, dragging the lakers with him, but as they neared the British, the wind suddenly kicked up and shifted in Yeo’s favor. Yeo quickly formed a line and started for the Americans. Two of the lakers, off their tow, missed a signal and sailed toward the British. They were quickly captured, and the two sides broke off the engagement.

Although there had been no real action, Yeo had clearly won on points. Including the capsized schooners, Chauncey had lost four lakers with upward of two hundred men and 26 guns. A string of anonymous complaints about Chauncey’s timidity, apparently from crewmen, found their way into public press.

The two fleets spotted each other several times over the next couple of weeks, but without an engagement. Toward the end of August, Chauncey more than made up for the loss of his lakers by the launch of the Sylph, a fast sailer with 18 guns, including 4 long 32-pounders on swivels.

On September 11, returning from Niagara, Chauncey spotted the British fleet becalmed near the mouth of the Genesee River on the American side of the lake. The

Pike and the

Sylph closed within three-quarters of a mile and began to pound away with their long guns. The lakers, dragged along for just such an engagement, once again did not get into the action. A land breeze kicked up in time for the British to escape with only modest casualties and damage. The Americans gave chase across the lake, breaking off when Yeo tried to set an ambush behind some islands on the Canadian side. Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote a small masterpiece on the naval war, was no fan of Chauncey, but he mocked Yeo’s battle report for failing to admit that his fleet “ran away.”

20 Prevost complained to London of his “disappointment” at Yeo’s “having been so many days in sight of the enemy’s squadron without having obtained a significant advantage.”

21On September 28, the fleets met again while both were on transport duty in the lake’s western end—Yeo on the northern side sailing eastward and Chauncey to the south but moving northwest. There was a strong easterly wind, so Chauncey had the weather gage.

d Yeo turned southward, while Chauncey ran north and then turned, with the

Pike in the lead, to approach Yeo at an angle with the wind. Both sides cleared their decks for battle. This time Chauncey did not attempt to stay at long range but sailed right into the

Wolfe’s broadside, taking fire from the

Beresford and

Royal George at the same time. At a distance of several hundred yards, the

Pike veered to unleash a full powerful broadside. The

Wolfe reeled, and the

Pike lost part of its topmast. A second exchange of broadsides took down the

Wolfe’s whole topmast. The

Wolfe “staggered and lost its heading . . . its deck a scene of chaos,”

22 as the

Pike closed in for the kill.

At that moment, the Wolfe was all but lost. A major mast in the water effectively anchored the ship. Until its frantic crew could chop away the dense tangle of thick ropes that held the mast, it was utterly exposed to the Pike’s heavy guns. With the Wolfe out of action, the rest of the British fleet could not stand against the Pike, the Madison, and the Sylph. Chauncey, as hungry for glory as any captain, suddenly had the lake, and possibly the war, in his grasp.

Yeo was saved when his number two, William Mulcaster, arguably the best sailor on the lake, darted the Royal George between Chauncey and Yeo and fired his broadside on the Pike, giving Yeo a respite to regroup. There was a disorganized melee on the Wolfe for some fifteen minutes, while the crew got free of its shattered masts and cleared away its dead and wounded. By then the Madison and the Oneida were in the fray, and the easterly wind a gale. Yeo signaled the fleet to make an all-out run to Burlington, a harbor on the far western shore. Off they went, with the Americans in chase, covering fifteen miles in ninety minutes, an extraordinary pace for square-rigs. Spectators on shore dubbed the episode “the Burlington Races.”

The Americans were hampered by Chauncey’s insistence on towing the lakers, which seems clearly wrong. Neither the Sylph nor the Madison could stay abreast during the chase, so it was only the Pike, which had absorbed most of the British gunnery during the battle, that was in truly hot pursuit, although leaking badly, with cut-up rigging and topmasts. Chauncey’s hope of a glorious victory disappeared when one of his big guns exploded, killing or wounding twenty-two men. With several others showing cracks, Chauncey finally gave up the chase. His fleet then faced a long struggle into the teeth of the gale to get back to the safety of the natural harbor at Niagara.

“The battle, if such it may be called,” Roosevelt wrote, “completely established Chauncey’s supremacy, Yeo spending most of the remainder of the season blockaded in Kingston.” By Roosevelt’s count, the Americans enjoyed unrestricted movement on Ontario for 107 days in the 1813 sailing season, while the British had only 48 days, and another 69 days were contested.

23 And despite the complaints about Chauncey’s caution, his attack on the

Wolfe was arguably the single most aggressive naval action during the entire Lake Ontario face-off.

Chauncey finally enjoyed a crowning bit of luck. On his return to Sackets a week later, his squadron ran into a large British transport caravan, guarded only by gunboats. The

Sylph quickly rounded them up, costing the British a substantial shipment of military stores and 252 prisoners. The loss put Yeo in a rage, for as a British historian writes, he “had suffered a series of setbacks quite unlike anything in his career to date.”

24The truly momentous news of that fall, however, came from Lake Erie, for just before Chauncey and Yeo engaged in their September quasi-combat, news filtered in that Perry had cleared the British from the lake.

The Battle of Lake Erie

The opposing commanders on Erie, Oliver Hazard Perry and Robert Heriot Barclay, were both in their late twenties and both rising stars. Perry had been with Stephen Decatur, then a captain, at Tripoli during the Barbary War, and Barclay had lost an arm at Trafalgar. Both developed testy relationships with their respective superiors, Chauncey and Yeo, because they felt shortchanged on men and materials.

When Perry took command, he had the captured gunboat Caledonia (3), and a handful of other gunboats that Eckford and Elliott built at the village of Black Rock, on the Niagara River near the entrance to the lake. The British had three warships on the lake, with 38 guns between them. The American victory at Niagara in May, however, had chased the British from Ft. Erie, an artillery outpost that covered the lake entrance. With the fort in friendly hands, Perry could tow his little Black Rock armada onto Lake Erie. (The current flowing out from the lake, on its way to the falls, is very strong. The tow took several weeks with oxen and two hundred men pulling from the shoreline.) From there, it was a hundred-mile sail to a new American base at Presque Isle, near the present Erie, Pennsylvania. Barclay was prowling the lake to prevent just such a move, but dense fogs helped the Americans slip through.

Presque Isle was far from an ideal base. It was protected by a sandbar that allowed only five to eight feet of clearance: enough for a gunboat but not a warship. Perry chose it because it was the only protected harbor on the American side of the lake, but it meant that new warships would have to be lifted over the bar before they could get into action.

Barclay’s position, despite his advantage in warships, was becoming untenable. He was dependent on uncertain supply lines that had been badly disrupted by Chauncey’s raids on York. His supply problems were made much worse by Yeo’s high state of nervousness, for he regularly preempted men and weapons that the Admiralty intended for Barclay.

Barclay maintained a watchful blockade much of the summer, while scrounging materials for a new 19-gun corvette, the Detroit. Perry stayed stuck behind his sandbar, building twin 20-gun corvettes, the Lawrence and the Niagara, armed almost entirely with carronades. For some reason, Barclay raised the blockade on July 29 and returned to his base at Amherstburg on the western end of the lake till August 4—just time enough for Perry to get his ships out. Crossing the bar was accomplished with “camels,” fifty-foot-long waterproof casks on each side of a ship’s hull. The camels were filled with water and sunk; when they were pumped full of air, they raised the whole ship.

With Perry’s fleet on the lake, Barclay was doomed. As shown in

Table 1.3, even though the British had more guns, the Americans had twice the firepower, although concentrated in carronades.

TABLE 1.3 Naval Forces, Lake Erie: September 1813

Barclay retired to Amherstburg to finish the

Detroit, while railing at Prevost and Yeo over his lack of men and supplies. The

Detroit was armed mostly by cannibalizing guns from the Amherstburg fort; they were missing locks and had to be fired by flashing pistols next to their touch holes.

e Although Barclay also complained bitterly of the quality of his men, both forces acquitted themselves well. It was a close-run fight, one that Perry nearly lost and probably deserved to.

Perry maintained a loose blockade on Barclay’s base at Amherstburg while the Detroit was being finished. Barclay finally brought his ships out for battle on September 9. Ready or not, Amherstburg was running out of food. The fleets spotted each other mid-morning the next day and cleared for battle. Barclay kept his ships in a tight line, while Perry, in the Lawrence, attacked with the weather gage, in a light wind, closing on a parallel line to get close enough to use his carronades.

Perry’s line started with two gunboats with 3 heavy long guns between them, followed by the Lawrence, the Caledonia, the Niagara under Elliott, and then the rest of the gunboats. Perry’s original line had the Niagara in second position, but he changed it at the last minute. The Caledonia, however, was a notoriously slow sailer: with Elliott keeping his third position, the Lawrence quickly pulled far ahead of the rest of the squadron.

Perry took a number of hits as he closed to carronade range. Then he stood broadside to broadside against the Detroit, the Queen Charlotte, and the Hunter for some two and a half hours. The long guns on the gunboats worked severe damage on the British warships—Roosevelt argues that they were decisive—but the British fire was concentrated solely on the Lawrence. Between the gunboats and the Lawrence’s heavy carronades, the Hunter was put out of the battle and the Detroit and Queen Charlotte severely battered. But the Lawrence was a complete wreck—its sailing master called it “a confused heap of horrid ruins.” All of its guns were out of action and 80 percent of the crew killed or wounded, although Perry himself was unharmed.

At the point when the

Lawrence was clearly lost, Perry spotted Elliott finally coming up, his ship still virtually unscathed. He promptly had himself rowed to the

Niagara, sending Elliott back to organize the rest of the gunboats. Perry turned the

Niagara directly into the British line, unleashing broadsides from both sides. It was over in another half hour. The

Detroit and the

Queen Charlotte, with nearly all their masts already down, became tangled with each other. Wallowing helplessly, with the

Niagara coming about for yet another murderous broadside, both struck their colors. Barclay’s remaining arm was shattered in a wound the surgeons thought was mortal, but he stayed on deck almost to the end. His official report read in part: “The American Commander seeing that the day was against him ( . . . [the

Lawrence] having struck as soon as he left her) and all the British boats badly shot up . . . made a noble, and alas, too successful an effort to regain it, for he [changed ships and] bore up and supported by his small Vessels passed within Pistol Shot and took a raking position

f on our Bow, nor could I prevent it, as the unfortunate situation of the

Queen Charlotte prevented us from wearing, in attempting it we fell outboard her.” A junior lieutenant, George Inglis, the only officer still standing, completed the report: “Every brace cut away, the Mizen Topmast and Gaff down, all the other Masts badly wounded, not a Stay left forward.... I was under the painful necessity of answering the Enemy to say we had struck, the

Queen Charlotte having previously done so.”

25With the warships gone, it was a simple matter for the Americans to round up the rest of the British squadron. From that point, Erie was an American lake.

The victory on Lake Erie effectively cut off supplies to the interior of Canada. The British infantry commander on the spot, Col. Henry Proctor, correctly called it “calamitous.”

26 Low on supplies and cold weather gear, and unable to defend Amherstburg, he burnt the base and began a retreat northeastward, to the fury of Tecumseh. William Henry Harrison took a large force of Ohio and Kentucky volunteers in pursuit. Proctor fought an orderly retreat, but Tecumseh attempted to make a stand at the Thames River, where he was shot in the heart and reportedly skinned by Harrison’s frontiersmen. With him died the idea of a northwestern Indian alliance.

Perry’s courage was widely celebrated. He embarked on a national tour of parades and speaking engagements, and his victory became a fabled episode in elementary school textbooks. But the fact remains that the Lawrence and the Niagara, fighting together, greatly outgunned the British and should have scored an easy win. A vast literature sprang up on the questions of why Elliott hung back, for his record had been one of great boldness. Whispers of cowardice dogged Elliott throughout a long career, and Roosevelt assailed him for “misconduct.” (Elliott’s explanation was that he had initially held to his position as instructed and then lost his wind, which is plausible. Perry never criticized him but omitted the usual praise in his report.)

But Perry mismanaged the fleet. In the age of sail, light-wind battles were stately, slow-motion affairs, and Perry had ample opportunity to regroup his line. Barclay wasn’t going anywhere. As it was, Elliott’s diffidence and Perry’s solo heroics almost lost the battle and may have needlessly sacrificed the

Lawrence’s crew and officers.

27The 1813 sailing season on Ontario ended with Yeo blockaded in Kingston. Chauncey ferried troops for yet another misconceived infantry action, putatively against Montreal, and with much the same near-disastrous outcomes as in the previous summer.

The Arms Race Escalates

The most ominous developments for Americans, however, took place in Europe. After Napoleon’s disaster in Russia, the European wars had turned decisively in favor of the British and their continental allies. As 1814 opened with Napoleon all but defeated, the British turned with some pleasure to the task of inflicting punishment on the jackal former colony whose conduct had been “so black, so loathsome, so hateful,” as the London

Times put it.

28 There were large transfers of veteran ground troops and ships and seamen from the European theater. Naval forces up and down the American coast mounted punitive search-and-destroy missions up rivers and inlets, culminating in the burning of Washington in the late summer.

On the lakes, British war policy expressly shifted to the offensive, with the objective of moving the Canadian border southward and eastward. Much of the current state of Maine was already under British occupation. Yeo radically scaled up his building program, starting on two outsized frigates with 58 and 44 guns, four large new gunboats, and a massive ship of the line. During the winter of 1813–1814, in a rapid-strike campaign, the British army under Gen. George Drummond retook virtually the whole of the Niagara peninsula.

The Americans were determined to hold fast. In January, Chauncey got another carte-blanche general order from naval secretary Jones: “You are directed by the President of the United States . . . to make such requisitions, take such order and employ such means as shall appear to you best.”

29 The near-totally blockaded coastal fleet was stripped of crews, guns, and other supplies for the lakes, and substantial raises were granted to lake seamen and officers.

Both Chauncey and Yeo maintained a steady flow of alarms to their political masters, although Yeo—perhaps smarting from the naval failures of 1813—was much the more strident, to the point where Prevost felt constrained to correct his exaggerations. In truth, since Yeo did not wait for permission to start his winter build, he was months ahead of Chauncey (see

Table 1.4).

g30Yeo’s two new warships, the

Princess Charlotte and the

Prince Regent, decisively shifted the advantage. Bulked up by 68-pound carronades and 32-pound long guns, total British throw weight was now about 1.6 times that of the Americans, and they even had an edge in long-range firepower as well. At the same time, large transfers of Royal Navy veterans doubled Yeo’s manning complement and ratcheted up their skill level. The big force increment intensified pressures for success. The semiofficial

Naval Chronicle pointedly hoped that Britons would “not again be distressed at the recital of misfortune or failure from want of long guns” but would rather “soon be gratified with the glad tidings that his [Yeo’s] efforts have been crowned with success.”

31

TABLE 1.4 Naval Forces, Lake Ontario: May 1814

Chauncey, of course, had no intention of fighting. Snugly ensconced at Sackets, the base ringing with shipwrights’ hammers, his own oversized frigates rising in the boatyard, he could wait for better odds. Drummond and Yeo plumped hard for an attack on Sackets itself, which would require large reinforcements from Montreal. Prevost refused it as too risky. The two pressed their case through the summer and finally decided to attack the American depot at Oswego to help make their case.

The Oswego river empties into Lake Ontario about fifty miles west of Sackets Harbor and was the drop-off point for much of the ordnance and other supplies shipping through western New York. Losing it would have seriously disrupted American logistics. The American presence comprised a modest fort, storehouses, and a garrison of some three hundred marines and soldiers. The attack got underway on May 6 and involved Yeo’s entire fleet, some thirty vessels, including gunboats and troop transports. Chauncey was quickly made aware of the assault but decided he had to sit it out. Yeo had good intelligence on the defenses and went in with more than a two-to-one manpower advantage.

The postbattle reports from Yeo and Drummond border on the ecstatic: the attack was “a compleat success,” “nothing could exceed the coolness and gallantry in action, or the unwearied exertions,” and much else in that vein. In fact, it clinched Prevost’s case against an attempt on Sackets, which had been strongly reinforced over the winter. Oswego cost the British ninety casualties, a relatively high number. (The Americans had several of the rapid-firing Chambers guns.) For that, they sunk some transports, which were quickly raised, and captured seven heavy guns, some rope and other naval supplies, and several weeks’ supply of food, which the British badly needed. The loss of the guns delayed Chauncey’s big new ships by several weeks, but all the rest of the supplies were readily replaced.

32The British success at Oswego was offset three weeks later by a sharp reverse on the same shore. The American commander at Oswego, Lt. Melancthon Woolsey, had hidden substantial amounts of ordnance and other supplies before the attack, and more was arriving by the day. At the end of May, he decided to make a night run through the British blockade, taking nineteen boats escorted by a substantial force of riflemen and friendly Oneidas; Chauncey also sent a detachment of mounted dragoons to meet him. Woolsey was spotted en route and chased by a force of some 250 marines and seamen in two groups of small craft. He made it to Sandys Creek, a winding inlet with road connections to Sackets. The British foolishly followed and got trapped in an ambush. Their entire force, equivalent to the crew for a sizeable brig, was captured with very heavy casualties.

For all practical purposes, Sandys Creek marked the end of Yeo’s control of the lakes. Chauncey now had all his ordnance, and final preparation of two powerful new frigates, the

Superior and the

Mohawk, was proceeding apace. Chauncey had promised to be on the lake early in July but was taken seriously ill, with one of the fevers that regularly decimated Sackets.

h33 Fears for Chauncey’s recovery were such that Jones asked Stephen Decatur to transfer to the lake and take temporary command. In the event, on July 25, Chauncey was carried to his cabin on the

Superior and sailed forth once more as ruler of the lake, while Yeo retreated to Kingston.

The total American throw weight of metal (see

Table 1.5) was about 20 percent greater than that of the British, and they had more than double the long-range firepower. The long-range power of just the

Superior and the

Mohawk was greater than that of the entire British squadron, while the rest of the American fleet, no longer burdened with lakers, outgunned and could mostly outsail their opposite numbers. Yeo had no interest in taking on such a force; instead, he concentrated feverishly, almost fanatically, on building the ultimate naval weapon: a true first-rater.

The summer of 1814, especially from July through September, was a decisive period in the war. There were bitter, brutal land battles up and down the Niagara peninsula. Large forces were involved from both sides; Lundys Lane was one of the largest troop engagements of the war. Battles were fought to a standstill, and casualties were very high, especially among the Indians, who basically withdrew from the fighting.

i34

TABLE 1.5 Naval Forces, Lake Ontario: August 1814

The British had a modest numerical advantage most of the time but were taken aback by a new gritty, dug-in steadiness on the part of the Americans, even among militia units. American commanders made serious tactical errors throughout, but the British served their troops as badly, mounting one high-risk operation after another on the conviction that Americans always crumbled at the first exchange of fire.

The contribution of the massive Lake Ontario navies to these momentous engagements was effectively zero, since both commanders feared that supporting ground troops would dissipate their strength and put their fleets at risk. Jacob Brown, the American commander on Niagara, was so incensed by Chauncey’s refusal to support him that he took the argument to the press. Drummond and Prevost made the same complaints about Yeo, if more quietly.

35As it happened, there was one decisive naval battle in 1814, but it took place on Lake Champlain, with minimal assistance from either of the great establishments on Ontario.

The Battle of Lake Champlain

The Battle of Lake Champlain halted a major British invasion of the American northeast and ended parliamentary hopes of “rectifying” the Canadian border. The attack had two prongs: a naval assault on the American squadron at Plattsburgh on northwest Champlain and a ground invasion down the west side of the lake by some 10,000 regulars, many of them Wellington’s “best troops from Bordeaux.”

36 The war secretary, John Armstrong, acted with his usual destructiveness by transferring the bulk of the American ground forces away from Plattsburgh just before the invasion.

The British naval squadron, under Captain George Downie, was spearheaded by a new frigate,

Confiance; its 37 guns, 31 of them long-range 24-pounders, made it nearly as powerful as Chauncey’s

Mohawk. To offset

Confiance, Thomas Macdonough, commander of the Champlain squadron, ordered the construction of the

Eagle ; it was built by the Browns, from first keel-laying to launch, in just nineteen days. (See

Table 1.6.)

TABLE 1.6 Naval Forces, Lake Champlain: September 1814

At first, the campaign unfolded as planned. The infantry veterans brushed aside sporadic opposition as they moved down the western side of the lake, arriving at Plattsburgh within a few days of the naval squadron. Plattsburgh had a formidable arrangement of forts and redoubts, and the British assumed it would take about three weeks to carry them. But sieges in hostile territory are logistics-intensive; without control of the upper lake, Prevost could not secure his supply lines. From the outset, he had insisted that the campaign depended on taking out the American squadron at Plattsburgh.

The ensuing battle may be the only naval engagement of the war that turned almost entirely on a commander’s thoughtful battle preparation. The Plattsburgh harbor was on a bay sheltered from northerly winds. Macdonough anchored his vessels in a line broadsides out, in a narrow portion of the bay. The details of his positioning gave him two crucial advantages. The first is that he set kedges, or auxiliary anchors, with undersea cabling so crews could winch their ships around to change broadsides without losing anchorage. The second is that the narrowness of his anchorage site helped to neutralize the Confiance’s great advantage in heavy long guns. (Macdonough implicitly counted on the British penchant for attacking without regard to tactical details.)

The British ground forces were mostly in position, but the siege had not commenced, when Downie’s squadron appeared up the lake in the early morning of September 11, running before a brisk wind. The American masts were visible over the promontory that protected the bay, so the squadron sailed past the promontory, turned to the starboard, and proceeded directly into the bay. They lost their wind and set anchors in a line facing Macdonough’s at a distance of three hundred to four hundred yards. Both sides cheered and opened fire.

After some two hours of pounding, both squadrons were near-wreckages, and casualties were high—Downie was killed in one of the first salvos. The weight of the

Confiance was taking its toll. Although badly cut up itself, it had silenced the guns of Macdonough’s flagship, the

Saratoga. But instead of striking colors, Macdonough set his crew to the winches, and the

Saratoga swung around to present a completely fresh broadside. Pounded anew, and increasingly defenseless itself, the

Confiance tried a similar maneuver but got hopelessly stuck and was forced to strike. (An officer of the

Confiance reported that its men “declared that they would stand no longer to their Quarters”—a remarkable defiance for British seamen.

37) The Americans quickly finished off the

Linnet and rounded up the smaller vessels. Only a few gunboats escaped.

Prevost had not yet signaled the assault on the forts when he saw his navy surrender. He immediately broke off the action and ordered a retreat, infuriating the veterans and most of his officers, although he had been quite clear on his conditions for a siege. Even Wellington later conceded that it was a correct decision.

With the failed invasion, the apparently permanent loss of both Erie and Champlain, and the standoffs on Ontario and the Niagara peninsula, Parliament’s avowed objective of punishing America began to look like a very expensive self-indulgence.

Denouement

The last act of the 1814 sailing season, as imposing as it was inconsequential, came in October, when Yeo finally sailed out from Kingston in his new first-rater, the HMS

St. Lawrence, “a behemoth of oceanic proportions, more powerful than Nelson’s flagship at Trafalgar.”

38 It bristled with 112 guns, almost all of them very heavy, arranged in three gun decks. At a stroke, the fleet’s throw weight of metal increased by 55 percent, and its long-range firepower was more than doubled. Chauncey duly took his own armada back to the shelter of Sackets, and for a few weeks before the ice set in, the lake was Yeo’s to sail in unopposed majesty.

The Americans were determined to stay in the game. By late fall, Sackets was a beehive, laying down two first-raters and two large frigates, building a rope works, and constructing a second shipyard, including housing, shops, and other facilities. A British spy, “our friend Jones,” who also reported on his tête-à-tête dinners with top American generals, carefully paced off the measurements of the Sackets first-raters. (He also noted that “the great mass of the seamen appear to be coloured people.”

39) Yeo’s shipyard master, Capt. Richard O’Conor, in the meantime went off to London to warn the admirals of the “very considerable . . . exertions of the Enemy.”

40

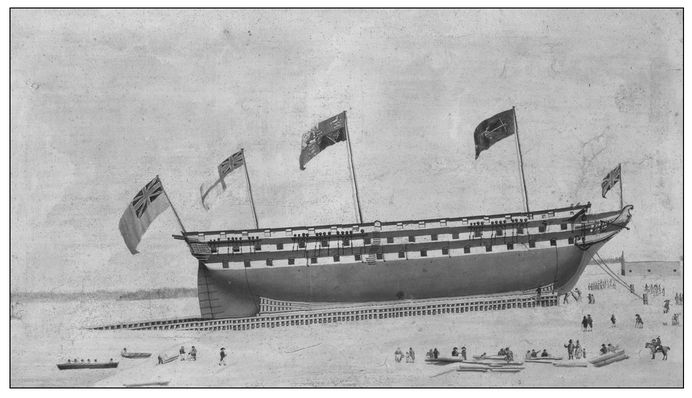

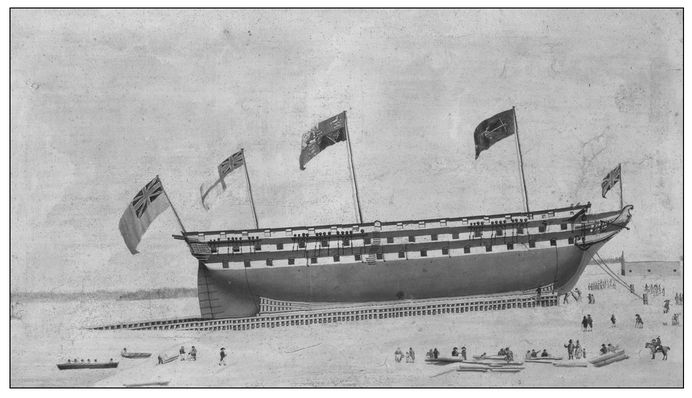

The St. Lawrence, a true British “first-rater,” bristling with 112 gunports, was one of the largest ships in the world when it was launched down a Lake Ontario slipway in the fall of 1814. It was bigger and better-armed than Nelson’s flagship at Trafalgar, but never fired a shot in anger. When the peace treaty was signed a few months after its launch, it was left to rot on the beach until it was disposed of in 1832.

But second thoughts abounded. Prevost complained in October that outfitting the

St. Lawrence had “absorbed almost the whole of the Summer Transport Service from Montreal,”

41 superseding far more pressing supply issues. And even Jones pleaded to Madison for a rethink of what had “become a warfare of Dockyards.” “We are at War with the most potent Naval power in the world,” whose global network of supplies and ordnance meant it could easily meet any demand “in less time and at one fourth the expense” as the Americans. Jones estimated that the next summer’s lake fleet would require 7,000 seamen, which he saw no possibility of supplying.

42More practically, the American government was broke. Lake seamen and troops had not been paid for six months or more, and the militias, Chauncey wrote, “desert by companies.”

43 Eckford and the Browns had signed personal notes for $110,000 to cover payments to critical suppliers. In early February, the three of them wrote that they were bearing a weekly expense of $8,000 and would “certainly be oblig’d to stop the whole business in ten or twelve days if we are not Supply’d with money.”

44The British were making their own calculations. The cabinet guessed that winning the war would cost another £10 million. The commercial community was strongly opposed to further taxes. They were moaning over the loss of their American markets and beginning to grasp how the war and years of blockades had been force-feeding American manufacturing.

American and British negotiators had been meeting desultorily at Ghent since August. Each side had come to the meetings with lists of non-negotiable items, with the British especially obdurate and supercilious. After months of whittling away at each other’s demands, they finally agreed on Christmas Eve to drop all preconditions, cease hostilities, and refer any outstanding issues to commissions—in effect, to forget the whole thing.

The climactic battles of New Orleans were fought in mid-January, and news of the great victory spread throughout the country within weeks. When news of the peace finally arrived on February 14, the public naturally assumed that New Orleans forced the British to quit, so the war ended on a high note. Across the Atlantic, the new disaster just reinforced the wisdom of getting out. Great Britain had spent two decades more or less continuously at war. The fulminations of the Times notwithstanding, a war of attrition against a major trading partner on a point of honor made no sense.

By the time of the peace announcement, Chauncey had launched the New Orleans, even bigger than the St. Lawrence, although it was still being masted. A yet-unnamed companion first-rater was also being readied for the spring thaw, and the keel was laid down for another big frigate. Across the lake, Yeo was determinedly keeping pace, building another first-rater and apparently a third-rater (74).

News of the peace also brought notice of Yeo’s recall. Since American roads were in decent shape, he decided to cross the lake and embark from New York. Chauncey invited him to stop over at Sackets, and they spent more than a week together. One imagines they had much in common, including shared grievances on interservice rivalries.

The dismantling of the lake’s naval establishments was underway by the end of February. The Americans sold off most of their gunboats and transport craft to commercial shippers, and both the Oneida and the Sylph had long careers as merchant vessels. Most of the rest of the warships were sold as scrap, and some were just left to rot. The hulk of the St. Lawrence was sold in 1832 for £25, on condition that it be removed from the lake. The New Orleans was planked over to preserve it and it sat on the beach until 1880, when it collapsed and was carted away.

The controversies over the performance of the two lake commanders melted away with the war. With Europe at peace, British commands were scarce, but Yeo was given an independent command interdicting slavers; he died of yellow fever in 1818. Chauncey was appointed commodore of America’s second saltwater ship of the line, the USS Washington (74), and assumed command of the squadron in the Mediterranean. He spent another twenty-five years in the naval service.

THE SHIPBUILDERS’ WAR IS A MOSTLY FORGOTTEN SUBPLOT OF A NEARLY forgotten war. But it cast a long shadow. The apparent victory, as Americans saw it, was a huge boost for national morale. More substantively, the war effort and the associated British trade embargo were robust stimuli to the still-fledgling native textile and iron industries. Military uniforms, tents, and the like created a New England textile boom, while foundries turning out cannon and cannon balls, shot, ship ballast, and wagon and ship fittings proliferated in a ring from Pittsburgh through upper New York State and western Connecticut. Military procurement accelerated the commercialization of agriculture, and the war broke the British-Indian alliances in the old Northwest territories, hastening the pace of settlement.

The war resolved a long-standing division over the importance of industry to the country’s safety and success. Even Thomas Jefferson repudiated his former distaste for industrial-scale manufacturing, forthrightly conceding that he was wrong to hope that sheer distance was sufficient defense against outsiders. The debacles in military procurement throughout the war spurred some serious rethinking among the professional military and were a factor in the determination to increase the use of machinery in military procurement.

Most important, the war and its outcome helped banish the remnants of a colonial mind-set among Americans. Theirs was a free and independent nation with a glorious future. British power was still overwhelming, especially after the victories over Napoleon. But Americans contemplating the continent lying open before them, and the energy and prosperity in so much of the country, might foresee a day when the two countries would measure themselves against each other.

BEFORE TRACING THE PATH OF AMERICAN DEVELOPMENT, WE WILL FIRST examine industrialized Great Britain, the day’s “hyperpower” and the only nation that had reached the heights America aspired to. The British development story differed in important ways from the one that evolved in America, and those differences highlight certain British dispositions that would serve them poorly in the inevitable economic contest with the United States.