New evidence has been discovered that destroys the credibility of the primary account of Lewis’s death—James Neelly’s letter to President Jefferson. (See pp. 234–35 to read the letter.)

Thomas Danisi, the author of a new book, Uncovering the Truth about Meriwether Lewis, disputes our interpretations of the evidence.3 Danisi and I appear to have independently discovered that Neelly’s letter to President Jefferson was actually written by Captain Brahan. We interpret it quite differently.

Danisi and other historians 4 are on record as opposing the exhumation of Lewis’s remains in order to determine the cause of his death. Over 200 members of Lewis’s family have requested an exhumation. Perhaps with this new evidence coming to light, the historians will now agree there is sufficient reason to support the family’s request for exhumation.

Danisi’s new book is a scholarly work. Because he believes that Lewis’s suicide was accidental, he has no preconceived notion of suicidal tendencies and provides good information about Lewis’s life after the expedition. However, in the interest of clarity, I am going to highlight some of the points on which we disagree and speak directly to these issues.

(1) Q. Was James Neelly a man of good character?

A. No. Both Captain Gilbert C. Russell and Lewis’s stepbrother John Marks accused him of wrongdoing in regards to Lewis.

Danisi argues that James Neelly was a man of good character. Neelly was the Indian Agent who escorted Lewis on his last journey. Danisi calls Neelly’s accompanying Lewis “a simple act of kindness.” 5 But the commander of Fort Pickering, Captain Gilbert C. Russell, wrote President Jefferson that he blamed Neelly for Lewis’s death by suicide. (See pp. 248–49.) Russell wanted to send his own man with Lewis as an escort for the entire trip to Nashville. There was no need of Neelly’s services. He wrote that if his man—who went with Lewis only as far as the “Nation” (the Chickasaw Indian Agency)—had been allowed to accompany Lewis all the way to Nashville, things would have turned out differently. He wrote:

Unfortunately for him this arrangement did not take place, or I hesitate not to say that he would this day be living….

Russell’s man returned to Fort Pickering from the Chickasaw Agency with news of Neelly encouraging Lewis to drink and Russell told the president:

…instead of preventing the Govr from drinking… from everything I can learn gave the man every chance to seek an opportunity to destroy himself.

Russell also accuses Neelly of stealing Lewis’s possessions—and perhaps, his money:

This Neelly also says he lent the Gov’r money which cannot be true as he had none himself & the Gov’r had more than one hund. $ in notes & species besides a check which I let him have of $99.58 none of which it is said could be found.

Neelly used the pretext that he had loaned Lewis money to justify taking Lewis’s valuables. Captain Russell wrote to Jefferson he had authorized a gentleman to pay the “pretended claim” and get back the pistols from Neelly.

Neelly had Lewis’s pistols, horse, rifle, and dirk[knife] according to a letter written by Lewis’s stepbrother, John Marks, to Lewis’s brother, Reuben Lewis on January 20, 1812.6 John Marks wrote he had traveled to Tennessee in December, 1811:

… into the Duck River country in Search of Mr Nealy to recover the property of Br ML which he had in which I failed in fact. [as N himself was at the agency house at the Chickasaw Nation for although I got a part of the property (to wit the horse & gun)] Nealy himself lives at the agency house in the Chickasaw Nation and as I was informed carries the dirk and Pistols constantly with him. the horse and rifle were given up to me by Mrs. Nealy, both of which I have brought to Albemarle.

There is an undated, unsigned handwritten note in the Lewis-Marks collection at the University of Virginia that reads:

Majr James Neely former agent of the Chickasaw Nation has Mr. M. Lewis’s gold watch and pistols.

Neelly enjoyed carrying Lewis’s elegant pistols, and apparently his gold watch. It was a constant reminder of his role in the death of Meriwether Lewis.

(2) Q. Can “Neelly’s” letter to President Jefferson reporting the news of Lewis’s death be trusted, despite the fact that John Brahan wrote it?

A. No, it was meant to conceal a conspiracy to assassinate Meriwether Lewis.

Danisi calls this letter, written on October 18, 1809, a “solid 200 year account,” even while acknowledging it was written by Brahan.7 In January, 2011, I discovered Brahan wrote Neelly’s letter and communicated this to Tony Turnbow. The news that Neelly was in court on the day of Lewis’s death caused me to examine my files again. I had copies of the letters written by Neelly and Brahan, but dismissed the obvious fact that the letters were written in the same hand as irrelevant. I didn’t question it, because the Neelly letter is the foundation document of the story of Lewis’ death. But Turnbow’s discovery opened my mind. You may examine the two letters at the Thomas Jefferson Papers on the Library of Congress American Memories website (www.memories.loc.gov). Enter the names of James Neelly and John Brahan in the search box separately.

So, now we have a dilemma—is the account of Lewis’s death to be trusted, despite the fact it was not written by James Neelly? In the years after my initial research, I acquired copies of Neelly’s correspondence with the Secretary of War, whose department supervised Indian Agents. I knew Neelly had written a letter on October 18th, 1809 dated at the Chickasaw Agency in his own handwriting, but again I fooled myself. It shows the power of trying to reconcile information with “accepted truth.” It was only Turnbow’s discovery that jarred my thinking loose. I hope that the new evidence in this book will do the same for its readers. I will discuss Neelly’s Chickasaw Agency letter in #4, and speculate about Brahan’s involvement in a conspiracy to assassinate Lewis in the next section.

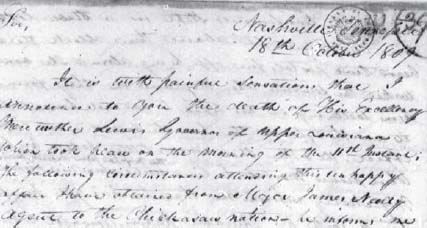

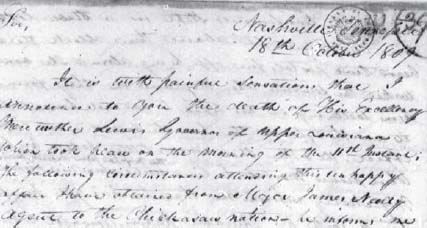

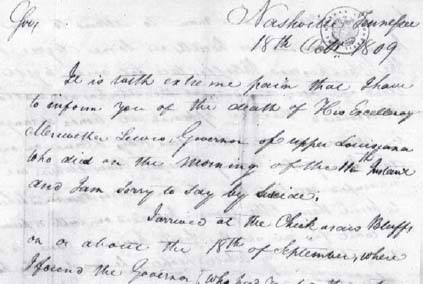

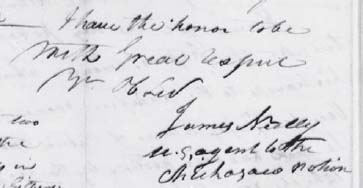

John Brahan’s letter to President Jefferson, signed in his own name, is seen here in the first excerpt. The next excerpt is the letter Brahan wrote in the name of James Neelly to President Jefferson. Due to age, the ink writing on the back side of each page makes it difficult to read.

John Brahan’s letter to President Jefferson

The letter written in the name James Neelly Brahan signed the letter with a signature that James Neelly never used, “James Neelly.” Neelly always signed his name “J Neelly” with the J attached to the N.

(3) Q. Where was Neelly on October 11, 1809, the date of Meriwether Lewis’s death?

A. He was in court at Franklin, Tennessee.

Danisi believes that Neelly did not appear in court as ordered, and instead was at Grinder’s Stand. Was Neelly looking for two lost horses on the Natchez Trace, as the letter written by Neelly—actually by Brahan—claims? Danisi believes the contents of the letter are correct, even if the authorship isn’t.

However, lawyer Tony Turnbow has made a startling discovery. Turnbow is a Lewis scholar and a native of Hohenwald, Tennesee. His family has lived in the area for almost 200 years. He practices law in Franklin. He became curious about what was happening in court around the time of Lewis’s death, and asked to see old records at the Williamson County Archives in Franklin. To his astonishment, he discovered that on October 11, 1809, James Neelly was appearing before a three man jury on a charge brought against him to recover a debt he owed. Neelly lost the case.

Danisi contacted Turnbow, asked him about his research, and then Danisi asked his nephew, Caesar A. Cirigliano, a lawyer practicing in Nashville, to investigate the court records.8 Cirigliano challenges Turnbow’s interpretation. He doesn’t dispute there was a jury trial, but he argues that it doesn’t prove that Neelly was present.

The conclusive evidence that James Neelly was in court on October 11th is that he had posted an appearance bond that he would appear in court. If he had not appeared, he would have forfeited his bond, and this would have been noted in the Minutes. Apparently Cirigliano never examined the original records, because Danisi states, “Neelly was under no obligation to attend.” 7 Turnbow examined the original files, which have since been scanned into the digital record of the archives.9

Franklin is about 55 miles east of Grinder’s Stand, the traveler’s inn on the Natchez Trace where Lewis died; it would have been a day and a half’s journey by horseback to go there. In the next section, I will present a map, and a hypothetical timeline and route for Neelly.

Danisi argues that Neelly was not in court—that he was traveling on the Trace towards Grinder’s Stand—and that the letter written by Brahan can be taken as a true account. The Neelly letter (written by Brahan) says:

I came up some time after & had him as decently Buried as I could in that place.

What does Danisi say about it? He says, without any proof of the date:

On October 11, 1809 after burying Lewis, Maj. Neelly and party departed Grinder’s Inn and made their way to Nashville with Lewis’s belongings. 10

Danisi wants us to believe that Neelly was at Grinder’s Stand on the day of Lewis’s death, and that he went from there to Nashville. He offers no explanation as to why Brahan would write a letter for Neelly—except, of course, the obvious reason that Neelly wasn’t in Nashville to write it.

(4) Q. Where was Neelly on October 18, 1809, when the letter was written in his name at Nashville to President Jefferson?

A. He was actually at the Indian Agency near Pontotoc, Mississippi writing his own letter to the Secretary of War, regarding a thief who stole saddlebags containing 621 silver dollars. 11

Danisi says that Neelly was in Nashville with Captain Brahan. However, the story of the “stolen saddlebags,” is critical to establishing where Neelly was on October 18th. It also establishes where both Neelly and Meriwether Lewis were on October 3rd, five days after leaving Fort Pickering.

The letter is linked to an advertisement that appeared in The Nashville Democratic Clarion on October 20th.12 The ad appeared in the same issue that reported the news of Governor Meriwether Lewis’s death. It is an interesting quesion—What was so important about the ad that it not only appeared in the Nashville newspaper, but it would also be placed in the newspapers of Natchez and New Orleans? The text of the ad is in the form of a legal deposition concerning the reputation of James Colbert and the case of the stolen saddlebags.

Colbert was a member of the mixed-blood family which dominated Chickasaw Indian territory. Scottish trader James Logan Colbert had married into the tribe, and he and his family controlled the area. One son, George, operated a ferry across the Tennessee River on the Natchez Trace, and another son had a traveler’s inn on the south side of the river at the ferry crossing.

The text of the ad is dated October 3, 1809, which establishes that Major Neelly and Meriwether Lewis had reached the Indian Agency near Pontotoc, Mississippi by that date. Their party had left Fort Pickering, 100 miles northwest of the Agency, five days earlier on September 29th.

Who was Colonel Joseph VanMeter, and how much money was in the stolen saddlebags that were in the safekeeping of James Colbert? He was a friend and neighbor of President James Madison in Virginia,13 and the amount of money was 621 silver dollars. The theft occurred on September 20th. Leonhart’s trial was held in Nashville on November 3rd, 1809. 14

The money was probably intended to buy land in the Muscle Shoals-Huntsville, Alabama area of the Great Bend of the Tennessee River. A public land sale was taking place and speculators were arriving from all the country.15 Captain John Brahan had been appointed Receiver of Public Money for the land sales by Secretary of Treasury Albert Gallatin16—the same Captain Brahan who wrote the letter in Neelly’s name at Nashville. Thomas Freeman, who signed for Lewis’s possessions after his death (pp. 236–238), was the government surveyor.17

Nashville Democratic Clarion, October 20, 1809

Chickasaw Indian Agency, October 3, 1809

Sometime in the month of September last, a pair of saddlebags belonging to col. [Colonel] Joseph Vanmeter was stolen from the house of James Colbert of the Chickasaws, and acknowledged to have been taken by George Lanehart, who is now in confinement of said crime, by order of major James Neely, United States agent to the Chickasaws.

We the undersigned, residents in the Chickasaw nation, and others who have been for very many years acquainted with James Colbert, at whose house the money was lost, certify that James Colbert has always conducted himself, and has been reputed as an honest man, and we conceive that no blame is, or ought to be attached to the character of Colbert or his family—let malicious characters report what they may.

Malcolm McGee,

Thomas Love,

Jeremiah K. Love,

James Gunn,

James Allen,

Thomas M’Coy,

Samuel Mitchel,

John Sphar.

J. Neely, United States Agent to the Chickasaws.

The printers at Natchez and New Orleans, will insert this and forward their accounts to me.

James Neely

On October 18th, James Neelly was most concerned with getting his money back from the War Department.18 He had paid $90 to a local young man, Jeremiah K. Love, to transport the man who stole the money and saddlebags to jail in Nashville. It was most likely Love who brough the ad to the Nashville newspaper office, as he was also one of its signers.

Neelly’s motive in paying Love was one of necessity. It was his responsibility to bring the prisoner to Nashville, but Neelly had other matters that needed his attention—escorting Lewis and his own court date. It is an irony of fate that he chose to write his letter to the War Department on the same day that Brahan was writing the “Neelly letter” in Nashville.

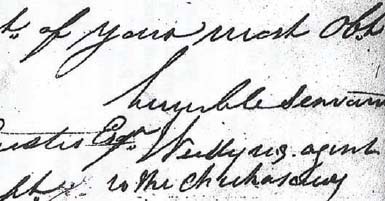

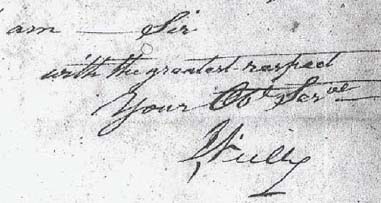

Chickasaw agency October 18, 1089

Sir: I have this day taken the liberty of Drawing on you in favor of Jeremiah K Love for service [$90 inserted on side of letter] rendered the united States by guarding and transporting George Linhard (a prisoner charged with felony) from the Chickasaw nation to Nashville and oblige (?) which draft I hope you will honour at sight and charge the same to acct of your most obt [obedient] humble servant.

The honbl [Honorable]

William Eustis Esq [Esquire]

Secty [Secretary] for the Dept of War humble servant,

J Nelly us agent to the Chickasaws

How does Danisi deal with this letter, and the problem of James Neelly being in two places at once? He says that Neelly’s Indian interpreter Malcolm McGee, wrote the above letter and states—

McGee wrote almost all the letters for Neelly, Chinumba and Colbert. For the first time it makes sense how Maj. Neelly could have been in Nashville on October 18 and also have a letter with that same date written from the Chickasaw Agency.18

This handwriting doesn’t look like the handwriting that Danisi identifies as McGee’s handwriting. The October 18th letter was received at the War Department on November 24th. Two more letters written by James Neelly at the agency, dated October 20th, were received at the War Department on November 16th. Danisi says that someone else wrote the October 18th letter, and it was held for Neelly’s signature. The travel time between Nashville and the agency was at least 11-12 days. He ignores the two other letters written on October 20th by Neelly at the agency, which were received at the War Department eight days earlier than the letter written on the 18th. To support his argument, he omits the letters of October 20th.19

(5) Q. What route did Neelly and Lewis take from Fort Pickering?

A. They stopped at the Indian Agency near Pontotoc, while en route to Franklin and Grinder’s Stand.

Danisi believes that Neelly took Lewis on a straight eastward path from Fort Pickering to the Natchez Trace, rather than going south to the Indian Agency before heading north on the Natchez Trace. Turnbow argues the Hatchie River formed a natural barrier between Fort Pickering and Nashville, and the road south to the Agency was the major road in the area at the time. A road east from Fort Pickering was established after Lewis’s death.20

Danisi says that it was “physically impossible” to go from Fort Pickering to the Chickasaw Agency to Grinder’s Stand in the alloted time (September 29th to October 10th.) He says the normal travel distance was 10-15 miles a day. The distance covered is approximately 250 miles. Twelve days of travel for 250 miles is an average of 22 miles a day.

Federal postal service and military riders covered 50 miles a day.21 Ornithologist Alexander Wilson, Meriwether Lewis’s friend, who visited Grinder’s Stand on May 6, 1810, traveled from Nashville to Grinder’s Stand, a distance of 79 miles, in a little over two days. He traveled six miles on the third day to arrive at Grinder’s Stand in the morning. So he traveled an average of 35 miles each day. He crossed one major stream, the Great Harpeth, and 10 or 12 large creeks on his first day. (See pp. 251–53 for his account of his visit to Grinder’s Stand.) He arrived at Natchez, Mississippi on May 18th, having traveled 444 miles in 14 days, an average of 32 miles a day.22 Danisi is simply wrong about how many miles could be covered in day’s travel on the Natchez Trace.

(6) Q. Why was the 1811 Russell Statement forgery composed? What was its purpose?

A. To cover up the tracks of the conspirators—it could only be used if Captain Russell were no longer alive to refute it. It was his virtual death warrant.

Danisi says the Russell Statement is authentic, even though the handwriting expert have established it is a forgery (pp. 137–39). It continues to be cited as a source of information written by Captain Russell in 1811. While at the same time, the two letters written by Captain Russell to President Jefferson in 1810—which contradict it—are ignored (pp. 246–49). General Wilkinson would be mightily pleased by the success of his “dirty tricks” two hundred years later! The Russell Statement was found in the University of Indiana Lily Library Archives by historian Donald Jackson in 1962, who included it in his Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.23 It has played a major role in defending the suicide theory ever since.

However—as a forgery—it is also the primary evidence connecting General James Wilkinson to the conspiracy to assassinate Lewis. The language of the statement is easily identified as written in the florid, over-the-top style of Wilkinson. The date of the statement, November 26, 1811, shows it was composed during Wilkinson’s court-martial at Fredericktown, Maryland. It was written by Wilkinson’s confidential scribe.

The same scribe (writer) wrote the General’s notes for his defense at the court martial. (See pp. 365–66 & Appendix A). Another researcher and myself have tried for years, without success, to identify the scribe. In my opinion, after examining the handwriting of many of Wilkinson’s contemporaries, it is characteristic of someone who was an engineer. Since the scribe wrote confidential documents for the General in 1808 and 1809, he was probably a military officer. 24

After I obtained the statement and other records from the court martial, I tried to figure out why General Wilkinson would suddenly decide it was necessary to have a false document prepared that had no relevance to his current court martial. What would cause him to create a clumsy statement written in the form of a deposition regarding the death of Lewis? I thought it was because Major Russell was a witness at the trial, and his presence had somehow alarmed Wilkinson.

Danisi devotes a great deal of attention to the Russell Statement. He claims Russell supported General Wilkinson when he appeared as a witness at the trial. Danisi wants to defend the Russell Statement as genuine—despite the testimony of the handwriting experts. Danisi writes the following account of Russell’s testimony at the court martial:

Russell testified on three separate days of the same month: Tuesday, November 5; Wednesday, November 20; and Saturday November 23, 1811. He maintained that Wilkinson’s conduct during the years he was in Mississippi and Orleans territories was exemplary and he also gave a character reference for Wilkinson.25

On the contrary—Russell did the exact opposite. He testified on November 5th:

About the last of March or beginning of April, 1806, I met with Mr. Hunt [Major Seth Hunt] at Hager’s Town, on his way from Louisiana to Washington City; we travelled together to the city; he expressed himself with violent resentment against the General, and said that he had a list of charges against him, sufficient to have him removed from office both in his military and civil capacity; he had a large pair of saddle bags which he said contained his charges and proofs; he further said that he had been extremely ill treated by the General and was on his way to the city determined to get satisfaction,—that his influence with members of Congress was considerable; and they must notice his charges, which were sufficient to remove the General from both his military and civil offices.

I recollect one Occurrence on the road, which it may be proper to mention, his horse fell with him and hurt him, in the midst of complaints of the hurts he received, he said there was one man in the world who would have rejoiced if he had been killed. I asked who that was? he answered Gen Wilkinson, for nothing but his (Hunt’s) death or some great accident to him could save Gen Wilkinson from ruin. We went to the city together; after his arrival I went in the Rhode’s Tavern one day and found him, reading to several gentlemen, either a petition from the inhabitants of Louisiana for the removal of Gen Wilkinson as Governor, or his, Mr. Hunt’s list of charges, I am not certain which; soon after I came into the room he stopped reading and put up his papers. He left the city a few days afterwards and I heard nothing more of his charges.

He uttered, in the general tenor of his conversation, the most abusive epithet against Gen Wilkinson; he alleged that Gen Wilkinson had tried to get him killed, and had set his officers upon him who had maltreated him, etc. 26

Perhaps Danisi never read this testimony: Russell was certainly not praising the General’s “exemplary” conduct—but it was a “character reference” of sorts!

Russell’s testimony that Seth Hunt said that Wilkinson “had tried to get him killed” is what set the General off. It is noteworthy that Major Hunt also testified at the court-martial, but said nothing about this. Hunt’s enemity to the General was well known and longstanding. The General must have truly feared what Major Russell might say next. Whatever documents Hunt was carrying to Washington in 1805, almost certainly related to the documents that Meriwether Lewis was carrying to Washington in 1809. 27

Major Russell’s testimony regarding his encounter with Hunt was an outright attack on the General. It indicated he was getting ready to go even further and charge the General with the assassination of Meriwether Lewis. That is the best explanation as to why the Russell Statement was created at Fredericktown on November 26th. If Russell were to die in the following days, it would be considered a valid statement of his understanding of the events surrounding Lewis’s death—his last words on the subject before his untimely passing.

What is the evidence for this idea? It is the astonishing fact that Major Russell is on record as being AWOL (Absent With Out Leave) from the U. S. Army from December 3rd to December 27th, 1811. And, yet—after going AWOL—he was promoted two weeks later on January 9th, 1812 to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, 3rd U. S. Infantry! 28

Wilkinson’s court martial ended on December 25th, with the military jury returning a verdict of “not guilty on all counts.” Two days later Russell returned to duty. He had disappeared for over three weeks after the statement was written, and only surfaced after the General was acquitted. It is reasonable to speculate that he went into hiding to save his life.

The statement was never used until it was discovered in the University of Indiana’s Archives in 1962. It took me a long while to realize that the statement only had value if Russell were not alive. I was only comparing it to the genuine letters written by Russell for factual information.

What are some of the contents of the Russell Statement that identify it as a “cover-up” for the conspirators? (pp.253–56)

(1) The despicable statement that Lewis committed suicide to deprive his enemies from the “pleasure and honour” of killing him.

He again beged for water, which was given to him and as soon as he drank he lay down and died with the declaration to the Boy that he had killed himself to deprive his enemies of the pleasure and honour of doing it.

(2) That Russell, learned from the boat crew that Lewis had made two attempts to kill himself before arriving at the fort.

The Subscriber being then the Commanding Officer of the Fort on discovering from the crew that he had made two attempts to Kill himself, in one of which he had nearly succeeded, resolved at once to take possession of him and his papers, and detain them there until he recovered, or some friend might arrive in whose hands he could depart safely.

Two hundred years ago they knew a characteristic sign of suicide was several previous attempts. Thomas Streed, an expert on suicide psychology, discusses this allegation of attempted suicide in his Coroner’s Inquest testimony (p. 89-90).

Captain Russell makes absolutely no reference to any attempted suicides in his letter to President Jefferson, dated January 4, 1810 (pp. 246–7). He begins the letter:

Conceiving it is a duty incumbant upon me to give the friends of the late Meriwether Lewis such information relative to his arrival here, his stay and departure, and also of his pecuniary matters as came within my knowledge which they otherwise might not obtain …

William Clark received letters that he thought were written by Russell (pp. 242–43). The letters to Clark reported that Lewis attempted to commit suicide on his way to the fort; that Lewis was in a state of mental derangement for 15 days at the fort; and that he made out a will at the fort. The will said that Clark and William Meriwether were made executors of Lewis’s will and Clark should take possession of his papers. Clark searched in vain for this second will. Clark received these letters in late November. They were forgeries created by the conspirators, which were meant to convince Clark that Lewis had committed suicide. Their content is contradicted by the genuine letters of Captain Russell to President Jefferson.

The supposed attempts at suicide were reported in Captain James House’s letter to Frederick Bates, dated September 28, 1809 (p. 233). House said that Major Amos Stoddard met an unnamed person who told him that Lewis had made several attempts to commit suicide, which were prevented by this unnamed person. What is revealing is that House doesn’t say who it was—Major Stoddard met a man who prevented Lewis from killing himself several times, but House is not going to tell us the name of the person.

All the stories of “attempted suicides” identify documents as part of the cover-up—House’s letter to Bates, the letters Clark told his brother he had received from Russell, and the Russell Statement. The Russell Statement directly ties General James Wilkinson to the conspiracy to assassinate Meriwether Lewis, because it was created at Fredericktown, Maryland during Wilkinson’s 1811 court-martial, in the handwriting of Wilkinson’s confidential scribe. The general’s guilt—like that of the others in the conspiracy—is revealed by his cover up attempt rather than by more direct evidence.

1 Tony L. Turnbow, “The Man Who Abandoned Meriwether Lewis,” We Proceeded On, May, 2012, 38:2, pp. 20–31.

2 For the two letters to President Jefferson, see Thomas Jefferson Papers, American Memories, Library of Congress website. Search for James Neelly to Jefferson and John Brahan to Jefferson, both dated October 18, 1809. (http:///memory.loc.gov). Brahan to William Eustis, Secretary of War, see RG 107, M221, roll 18, B-589(4), National Archives and Records Administration. For his letter to Amos Stoddard, see Missouri History Museum, Amos Stoddard Papers; or see Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites, Vol. VII, p. 389. Only a typed transcript exists at the Missouri History Museum archives. The Brahan letters are discussed in Suicide or Murder?:The Strange Death of Governor Meriwether Lewis by Vardis Fisher (Swallow Press:Athens Ohio, 1962) in a chapter entitled “Captain Brahan Writes Three Letters,” pp 139-45. Fisher did not realize that Brahan also wrote the James Neelly letter, or he would have said four letters.

3 Thomas C. Danisi, Uncovering the Truth About Meriwether Lewis (Prometheus Books, Amherst NY, 2012).

4 A panel of historians at the annual meeting of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, held at Olive Branch, Mississippi, on October 3-6, 2009 opposed exhumation. Only Dr. John Guice supported Jane Lewis Henley’s appeal on behalf of the Lewis family for exhumation. Jane Henley is a past president of the foundation. The historians’ opinion was: “Let him rest in peace.” Dr. Guice is the editor, and a contributor to, By His Own Hand? The Mysterious Death of Meriwether Lewis (Oklahoma University Press, Norman, 2006).

5 Danisi, p. 160.

6 Lewis-Marks Collection, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville VA.

7 Danisi, p. 162.

8 Danisi, p. 163-64.

9 Masterson v. Neelly, 11 October, 1809, Williamson County Court Records, Williamson County Archives, Franklin TN. Turnbow writes: “The original court file contains the original note, complaint, attachment, and appearance bond.” See footnote #13 in his WPO article, p. 28.

10 Danisi, p. 164.

11 James Neelly to Secretary of War William Eustis, October 18, 1809. RG 107, M221, roll 27, frame 9225, NARA archives.

12 Nashville Democratic Clarion, October 20, 1809, Tennessee State Library Archives, Nashville TN.

13 Personal correspondence with James Van Meter, a descendant (1/30/2010). Do a Google search for Colonel Joseph Van Meter, or see http://chasreader.home.comcast.net/~chasreader/ps04_454.html for family genealogy stories.

14 Pleas at Nashville, November 3rd, 1809: United States of America vs George Leanheart. Roll M1315, U. S. District Count and Circuit Court Records. Tony Turnbow discovered these Nashville records at the NARA archives in Atlanta. Leanhart was charged in federal court because the theft occurred in Mississippi Territory, not the state of Tennessee.

15 Daniel S. Dupre, Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County, Alabama 1800-1840 (Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge and London, 1997). The land office was located in Nashville, with sales starting in August, 1809. Over $67,000 was received in six weeks from the sale of almost 24,000 acres sold at public auction. “Thomas Freeman was the single largest purchaser, paying over $18,000 for almost 8500 acres.” (p. 17, citing a Ph.D. dissertation by Frances Cabaniss Roberts, “Background and Formative Period in the Great Bend and Madison County,” University of Alabama, 1956.) Thomas Freeman was the government surveyor.

16 Danisi, p. 165

18 Danisi, p. 167.

19 The letters are found in the National Archives & Records Administration Record Group 107, M221, roll 27. The October 18, 1809 letter is frame #9225. The two October 20, 1809 letters are frames # 9220, and # 9223.

20 Turnbow, p. 23.

21 Turnbow, p. 24.

22 Clark Hunter, The Life and Letters of Alexander Wilson (American Philosophical Society, Independence Square, Philadephia, 1983), pp. 358–70. The letter is dated Natchez Territory, 18 May 1810. Through an error in a contemporary publication, historians often give an incorrect date of 18 May 1811 for this letter.

23 Donald Jackson, editor, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 1783-1854 (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 2 volumes, 2nd edition, 1978) pp. 573–75.

24 The scribe wrote letters for Wilkinson during the months of April-July, 1808, while they were in Washington. The letters are found in RG 107, M221, roll 33. The dates are: April 11, W-5(4); May 4, W-27(4); June 4, W-74; July 9, W-214 (4); July 22, W-215 (4). The scribe also has documents in M221, roll 27: May 9, 1809 (frame 9017), May 11, 1809 (frame 9018), February 23, 1808 (frame 9059), July 9, 1809 (frame 9056).

To see a document on the internet written by the scribe for Wilkinson, Google for The First American West: The Ohio River Valley, 1750-1820. It is on the Library of Congress American Memory website. Search for Wilkinson to Henry Dearborn, September 8, 1805. The letter was written in St. Louis and marked “Private.”

Earl Weidner has been enormously helpful in supplying documents written by possible candidates for the “unknown scribe.” It has served to rule out many names. The key characteristics of the handwriting are long t-bars, and an unusually straight and even baseline to the writing. See p. 256 for an example.

25 Danisi, p. 173.

26 A complete transcript of General Wilkinson’s court martial is available in typed transcript from the Frederick County Archives & Research Center, Frederick, Maryland. The court martial was held in Frederick, from September 2 through December 25, 1811. See sections 995-996 for Major Russell’s testimony on November 5th. The transcript was prepared at the National Archives in 1976.

27 William Foley, The Genesis of Missouri: from Wilderness Outpost to Statehood (University of Missouri Press, Columbia & London, 1989), pp. 163–65.

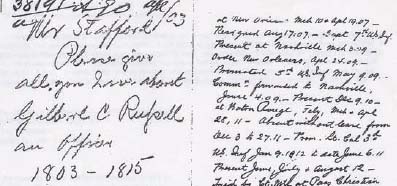

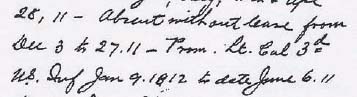

28 Gilbert C. Russell’s military record, is included in his file at the Department of Archives and History, State of Alabama. In handwritten notes dated 4-22-03, P. Stafford replied to a request from William Preble Hall, Assistant Adjutant General of Army to “Please give all you have about Gilbert C. Russell an officer, 1803-1815.” Stafford’s notes say “Absent without leave from Dec 3 to 27.11 Prom. Lt. Col 3rd US Inf Jan 9, 1812 to date June 6.11.” Hall had received a request from the Director of Archives and History at Montgomery, Alabama for information. He sent a typed response, the Military Record of the late Colonel Gilbert C. Russell, dated April 24, 1903, in which the record of Russell’s being AWOL is omitted. Two excerpts from the one page of notes are reproduced below.