The 20 documents in this section form the basic record of what is known about the last days of Meriwether Lewis’s life and the events surrounding his death—yet most are second-hand or even third-hand accounts. They are a mixture of truth, lies, rumors and outright forgery. Two hundred years have passed, and this is all the evidence that has been found, except for a few scattered accounts by others which are variations of Mrs. Grinder’s stories.

Did Meriwether Lewis commit suicide or was he assassinated, and are some of the documents part of a cover up? The November 26, 1811 Russell Statement (document 15, p. 253) often cited as evidence of suicide was neither written nor signed by either Gilbert C. Russell or Jonathan Williams whose signatures appear on it.

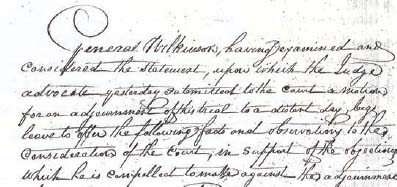

Documents examiner Jerry Richards has certifed that the “Russell Statement” is written in the same handwriting as that found in a 12 page court brief in the Jonathan Williams Archives at the Lilly Library at the University of Indiana (See Appendix). The so called “Russell Statement” and this court brief written about one month earlier were included among papers relating to General Wilkinson’s court martial held at Frederick Town, Maryland. It is most likely that the two documents were written by Wilkinson’s clerk.

There was no federal investigation of Lewis’s death, and no attempt was made to arrange for a Christian reburial in the family graveyard in Charlottesville, Virginia. His body remained in a lonesome, solitary grave near the place where he died. Meriwether Lewis was Governor of Louisiana Territory, one of the highest ranking officials in the federal government, and a national hero—why did this happen?

There was a local coroner’s inquest in 1809, but the records have been lost. Tradition has it that the jurors were afraid to name Robert Grinder as his murderer, fearing the consequences. Grinder was the owner of the roadside inn and tavern on the Natchez Trace where Lewis met his death on October 11, 1809. Supposedly he was away from home that night.

The accounts of Lewis’s death rely on three different versions told by Priscilla Grinder to other people. Grinder’s wife never claimed to have seen the shooting—only to have heard either two, or three, gun shots. (documents 4, 14, 18)

As for what she claims to have seen afterwards, John Guice, who testified at the 1996 Coroner’s Inquest, has since published an essay in By His Own Hand? The Mysterious Death of Meriwether Lewis, which adds new evidence to the scene of the shooting. On the night of October 10-11, 1809 it was one day past a new moon, and in the densely forested Natchez Trace, Mrs. Grinder could not have seen anything; it was pitch black. Her story of seeing Lewis crawling or staggering around the yard was not possible. Mrs. Grinder was undoubtedly lying, but did parts of her stories contain some truth?

Grinder’s Inn was a typical “dog trot house” consisting of two one room cabins, joined together by a common roof with a central passageway or “dog trot” in between the cabins. (See page 272 for a photo of the reconstructed building.) There was a kitchen out-building, “only a few paces from the house,” and a horse barn 200 yards away. The family lived in one cabin, and travelers stayed in the other one. In two accounts, Mrs. Grinder had decided to sleep in the kitchen building rather than in her cabin. The two servants accompanying Lewis slept in the horse barn. In all three accounts the gun shots happened in the middle of the night, in the early hours of October 11th.

One account mentions the presence of children. Alexander Wilson wrote that she told him she sent two of her children at daybreak to wake the servants in the barn. The most unlikely aspect of all these stories is the inability of the servants to hear gun shots at a distance of 200 yards. In the Neelly account, after hearing gun shots about 3 A. M. she goes herself to wake the servants. In the last account she is surprised the servants have not slept in the cabin with Lewis, but have instead slept in the horse stables, and they appear at her door at daybreak.

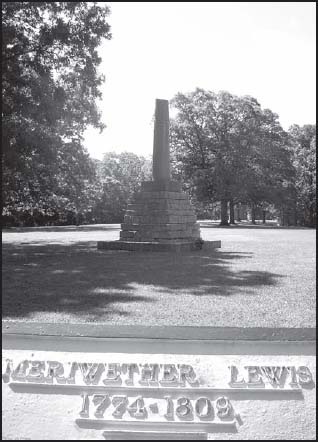

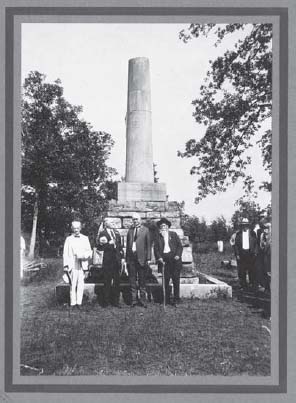

The first account (document 4, p. 234) is the letter written by Indian Agent James Neelly, who was acting as Lewis’s escort on the Natchez Trace en route to Nashville, Tennessee. Major Neelly—like Robert Grinder—was supposedly not present on the night of Lewis’s death. He showed up after daylight and arranged for Lewis to be buried near the place where he died. This site is the location of the Meriwether Lewis Gravesite & National Monument on the Natchez Trace Parkway near Hohenwald, Tennessee.

The second account (document 14, p. 251) was written by a friend of Lewis’s, the ornithologist Alexander Wilson who was traveling through the South sketching birds. He had planned to visit Lewis in St. Louis, but instead had the unhappy duty of visiting his friend’s gravesite six months after his death, where he interviewed Mrs. Grinder and paid for a fence to be erected.

The third account (document 18, p. 260) was published in a newspaper in 1845 and represents the story as told by a third person, a “teacher of the Cherokee Nation,” who interviewed Mrs. Grinder in 1838. Again, there was a new version of her story—this time told after her husband’s death.

This version included a visit by “two or three other men.” When they arrived at dusk, Meriwether Lewis immediately “drew a brace of pistols, stepped towards them and challenged them to fight a duel.” The men rode off. She said that Lewis’s body was found in old clothes after his death, and that his servant Pernier was wearing the same clothes Lewis wore when he arrived at the Inn and was carrying his gold watch.

It seems likely that Pernier was going to act as a decoy when he rode off the next morning. John Pernier was a free mulatto, half French, half African-American. He had been a servant in the White House in 1804-05, and had come with Lewis to St. Louis to serve as his personal valet. He has been accused of participating in the assassination. Lewis’s mother, Lucy Marks, thought so. Pernier brought the news of Lewis’s death to Lewis’s mother, Thomas Jefferson and President James Madison. Six months later he was dead. (document 13, p. 249).

Lewis’s gold watch and his brace of pistols—along apparently with his money—came into the possession of James Neelly, who refused to give them up. Lewis’s step brother John Marks visited Neelly’s home in 1811, but was unsuccessful in retrieving them, though he retrieved his rifle and his horse.

Thomas Jefferson wrote almost nothing on the subject until he was asked by the publisher of the Lewis and Clark Journals in 1813 to contribute a biographical essay on Meriwether Lewis (document 16, p. 257). Even though the former president accepted his friend’s death as a suicide, his words are contradictory and his famous words of praise for Lewis have much more meaning:

“Of courage undaunted, possessing a firmness and perseverance of purpose which nothing but impossibilities could divert from its direction.”

He must have terribly regretted the loss of his friend and protege, and yet it was not in the national interest to say that his death was an assassination. Particularly if the assassination had any connection with General James Wilkinson, the commanding general of the United States Army—who to the mystification of many observers—was supported by Jefferson throughout much of his career. The circumstances surrounding Lewis’s death are dealt with in Part Three of this book, where the complicated politics of this time period are discussed.

Three letters of William Clark are included here. They were written to his brother Jonathan in the weeks immediately following Lewis’s death. The last letter (document 9, p. 242) reveals the machinations of General James Wilkinson because Clark is responding to information contained in letters he believes were written by Captain Gilbert Russell, the commander of Fort Pickering where Lewis spent some of his last days. Their reported content—suicide attempts, mental derangement—is similar to the content of document 15 (p. 254), now proven to be a forgery which was mostly likely composed by Wilkinson under Russell’s name two years later. It may be assumed that the letters Clark received were also forgeries created by the General for the purpose of misleading Lewis’s best friend. These letters have never been found, so the handwriting cannot be analyzed.

The letters cleverly contained news of a “second will” written at Fort Pickering—which most likely was said to have given the Lewis and Clark expedition journals and papers to Clark. Though Clark searched for it, he never found this second will. He took over the project anyway. The letters he received have not been found, so an examination of the handwriting is not possible. But since Russell did not mention attempted suicides, mental derangement or the writing of a second will, in either of his two letters to Thomas Jefferson written in January, 1810 it indicates that other forgeries were written in his name.

It is highly likely that General James Wilkinson created the forged Gilbert Russell statement concerning the death of Meriwether Lewis dated November 26, 1811 (document 15, p. 253). The handwriting has been identified by documents examiner Jerry Richards as matching the handwriting of another document concerning the General’s court martial taking place at that time. It was most likely written by his clerk. Historians agree that the General used forged documents to destroy the career of General George Rogers Clark, the older brother of William Clark, and other forgeries by the General have also been suspected.

The “Russell Statement” aroused the suspicions of several historians—most notably Vardis Fisher, the author of Suicide or Murder? The Strange Death of Meriwether Lewis. It is the second most important document supporting the suicide story—the first being Neelly’s letter to Jefferson. The Russell Statement claims that Lewis made “two attempts to kill himself” while traveling to the fort and was in a state of mental derangement for 6 days while at the fort. The “Russell Statement” and the other document in the same handwriting are found in the papers of Colonel Jonathan Williams, an old friend of Wilkinson’s, who was the first Superintendent of the West Point Academy. Colonel Williams served as an associate judge in the General’s court martial, which took place at Frederick-Town, Maryland from September through December, 1811.

The General was standing trial on two matters not related to Lewis’s death: (1) that he was receiving pay as an double agent from the Spanish government; and (2) that his neglect of duty had resulted in the death and desertion of nearly half the soldiers under his command at Terre aux Boeufs in 1809. (Gayarre in his History of Louisiana states that out of 1953 regular soldiers, 795 died and 166 deserted. Terre aux Boeufs is the area of St. Bernard’s Parish east of New Orleans where Hurricane Katrina did so much damage in 2006.) Though the charges were actually true, Wilkinson was acquitted and returned to active duty. The General is known as:

“The General who never won a battle, and who never lost a court martial.”

Captain Russell did testify at Wilkinson’s court martial on November 26th. His brief testimony concerned the character of Thomas Power, a known Spanish agent and associate of Wilkinson’s. He stated that he did not know him, but he knew of his reputation. That was it. Did Gilbert Russell know anything about the forged statement written in his name? It doesn’t seem likely. His own letters to Thomas Jefferson (documents 10-12, pp. 243–249) are honest and sincere, and are essential in providing any understanding of the real circumstances surrounding Lewis’s death. His presence at the trial most likely inspired the General to create a new piece of evidence in his name (assuming the letters Clark received from Russell were earlier forgeries of his).

Some of the most loathsome words imaginable are found in this 1811 statement, words attributed to Captain Russell, who is supposedly reporting the last words of Meriwether Lewis:

“…he lay down and died with the declaration to the Boy that he had killed himself to deprive his enemies of the pleasure and honor of doing it.”

The implications are two fold—that the General felt the need to create some supporting evidence of prior suicidal intentions, indicating he was worried he might be charged with Lewis’s death and that he took “pleasure and honor” in killing Meriwether Lewis!

The court martial he was undergoing had absolutely nothing to do with Meriwether Lewis’s death. Which is exactly the reason I was curious about seeing a copy of the “Russell Statement” and examining the other Wilkinson materials in the Jonathan Williams Archives. Why was it found here? Why had it never surfaced before Donald Jackson published it in the Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition? The answer most likely is that Wilkinson had Williams keep it as an “insurance policy” in case he was ever charged with Lewis’s murder.

The letters written by Captain Russell to Thomas Jefferson in January, 1810 have never been published in their entirety. They are first hand accounts, and they are known to be written by the Captain. They provide a very different picture of Lewis’s last days and should be taken as a starting point in any reexamination of the historical record.

Professor Starrs has not taken a position on the cause of Meriwether Lewis’s death. I, on the other hand, believe it was an assassination. An exhumation of his remains could possibly settle the matter of whether it was suicide or murder, depending on what is found. In two previous examinations of his gravesite, it has been strongly suggested by those involved that they found evidence of assassination.

In 1848, when a Monument Committee appointed by the Tennessee State Legislature opened his grave, they stated that though it was commonly believed that Lewis committed suicide, “it seems to be more probable that he died at the hands of an assassin.” (document 19, p. 262)

In 1924, when the Meriwether Lewis Memorial Association successfully petitioned President Calvin Coolidge to make the gravesite a National Monument, they stated “Investigations have satisfied the public that he was murdered presumably for the purposes of robbery.” (document 20, p. 265)

In 1928, the Monument was refurbished and it was said that the Superintendent remarked “Isn’t it interesting that a man who killed himself shot himself in the back of the head?” This information is local lore, as reported in Lewis County, Tennessee, p. 13 (Turner Pub., Paducah, KY, 1995).

In each of these situations, the primary purpose was not to establish the truth concerning Meriwether Lewis’s death, but rather to honor him or to care for his gravesite. What is needed is an official exhumation of his remains to settle the matter, if it is possible to do so.

This is the letter that has been said to indicate suicidal tendencies because of the poor quality of the handwriting. See pages 126–140 for an analysis by Gerald B. Richards. The cost of printing the Territorial Laws was one of the items that the government was refusing to pay. Fort Pickering was located on Chickasaw Bluffs, the site of present day Memphis, Tennessee.

Chickasaw Bluffs, September 16, 1809

Dear Sir,

I arrived here (yesterday—inserted) about (2 Ock—crossed out) P.M. (yesterday—inserted) very much exhausted from the heat of the climate, but having (taken—inserted) medicine feel much better this morning. My apprehension from the heat of the lower country and my fear of the original papers of the voyage falling onto the hands of the British has induced me to change my rout and proceed by land through the state of Tennisee to the city of washington. I bring with me duplicates of my vouchers for public expenditures &c. which when fully explained, or rather the general view of the circumstances under which they were made I flatter myself (that—inserted) they (will—inserted) receive both (sanction &—inserted) approbation (and—crossed out) sanction.

Provided my health permits no time shall be lost in reaching Washington. My anxiety to pursue and to fulfill the duties incedent to (the—inserted) internal arrangements incedent to the government of Louisiana has prevented my wri (t—inserted) ing you (as—crossed out) (more—inserted) frequently. (Mr. Bates is left in charge.—crossed out) Inclosed I herewith transmit you a copy of the laws of the territory of Louisiana. I have the honour to be with the most sincere esteem your Obt. (and very humble—crossed out) Obt. and very humble servt.

Meriwether Lewis

James Madison Esq.

President U States

Major Amos Stoddard was an old friend. In this letter, Lewis asked him to repay $200 he had loaned him, and send it either to Washington before the end of December; or to St. Louis after that, indicating Lewis’s intention to return to St. Louis. However, Captain James House reports in a letter dated September 28th that Major Stoddard was in Nashville, and has heard rumors of Lewis attempting suicide and being mentally deranged.

Fort Pickering, Chickesaw Bluffs,

September 22nd 09

Dear Majr,

I must acknowledge myself remiss in not writing to you in answer to several friendly epistles which I have received from you since my return from the Pacific Ocean. Continued occupation in the immediate discharge of the duties of a public station will I trust in some measure plead my apology.

I am now on my way to the City of Washington and had contemplated taking Fort Adams and Orlianes in my rout, but my indisposition has induced me to change my rout and shall now pass through Tennessee and Virginia. The protest of some bills which I have drawn on public account form the principal inducement for my going forward at this moment. An explaneation is all that is necessary I am sensible to put all matters right.

In the mean time the protest of a draught however just, has drawn upon me at one moment all my private debts which have excessively embarrassed me. I hope you will therefore pardon me for asking you to remit as soon as convenient the sum of $200. which you have informed me you hold for me. I calculated on having the pleasure to see you at Fort Adams as I passed, but am informed by Capt. Russel the commanding officer of this place that you are stationed on the West side of the Mississippi.

You will direct to me at the City of Washington untill the last of December after which I expect I shall be on my return to St. Louis. Your sincere friend & Obt. Servt.

Meriwether Lewis

This letter, written before Lewis even left Fort Pickering, is the first evidence of a widespread conspiracy. Captain House says he met a person who says that he prevented Lewis from committing suicide en route to the Fort. It is interesting that House doesn’t give his name. The story is contradicted by the letters James Neely and Captain Russell wrote to President Jefferson (documents 4, 10-12). (Courtesy of Missouri History Museum, Frederick Bates collection).

Nashville, Sept. 28, 1809

Dr Sir

I arrived here two days ago on my way to Maryland—yesterday Majr Stoddart of the army arrived here from Fort Adams, and informs me that in his passage through the indian nation, in the vincinity of Chickasaw Bluffs he saw a person, immediately from the Bluffs who informed him, that Governor Lewis had arrived there (some time previous to his leaving it) in a state of mental derangement, that he had made several attempts to put an end to his own existence, which this person had prevented, and that Capt. Russell, the commanding officer at the Bluffs had taken him into his own quarters where he was obliged to keep a strict watch over him to prevent his committing violence on himself and has caused his boat to be unloaded and the key to be secured in his stores.

I am in hopes that this account will prove exaggerated tho’ I fear there is too much truth in it—As the post leaves this tomorrow I have thought it woud not be improper to communicate these circumstances as I have heard them, to you.

I have the Honor to be, Sir with much esteem & respect

Yr obe Serv.

JAS. HOUSE

Fredk Bates Esq

Secy of the Territory U Louisiana

This letter is the primary source for the story that Lewis committed suicide. Notice that Neelly makes no mention of two other versions of the story: that Lewis attempted suicide twice while en route to Fort Pickering; and that after shooting himself twice, Lewis began cutting himself with his razor.

James Neelly was the newly appointed Indian Agent to the Chickasaw Nation. His headquarters were located in the Chickasaw Towns at Pontotoc near today’s Tupelo, Mississippi. Neelly arrived at Fort Pickering “on or about” September 18th, 3 days after Lewis’s arrival. He stayed there for 11 days—for no apparent reason, until leaving with Lewis on September 29th.

Neelly owed his appointment as Indian Agent to General James Wilkinson, who was in charge of developing the Natchez Trace as a military road in 1801-03. Wilkinson was the highest ranking General in the U. S. Army, heaquartered in New Orleans; and Lewis’s predecessor in office as the Governor of Louisiana Territory.

Nashville Tennessee, 18th Octr. 1809

Sir,

It is with extreme pain that I have to inform you of the death of His Excellency Meriwether Lewis, Governor of upper Louisiana who died on the morning of the 11th Instant and I am sorry to say by Suicide.

I arrived at the Chickesaw Bluffs on or about the 18th of September, where I found the Governor (who had reached there two days before me from St. Louis) in very bad health. It appears that his first intention was to go around by water to the City of Washington; but his thinking a war with England probable, & that his valuable papers might be in dainger of falling into the hands of the British, he was thereby induced to Change his route, and to come through the Chickasaw nation by land; I furnished him with a horse to pack his trucks &c. on, and a man to attend to them; having recovered his health in some degree at the Chickasaw Bluffs, we set out together and on our arrival at the Chickasaw nation I discovered that he appeared at times deranged in mind. We rested there two days & came on. One days Journey after crossing Tennessee River & where we encamped we lost two of our horses. I remained behind to hunt them & the Governor proceeded on, with a promise to wait for me at the first houses he came to that was inhabited by white people; he reached the house of a Mr. Grinder about sun set, the man of the house being from home, and no person there but a woman who discovering the governor to be deranged gave him up the house & slept herself in one near it. His servant and mine slept in the stable loft some distance from the other houses. The woman reports that about three o’clock she heard two pistols fire off in the Governors Room: the servants being awakined by her, came in too late to save him. He had shot himself in the head with one pistol & a little below the Breast with the other. when his servant came in he says; I have done the business my good servant give me some water. He gave him some water, he survived but a short time. I came up some time after, & had him as decently Buried as I could in that place. if there is any thing wished by his friends to be done to his grave I will attend to their Instructions.

I have got in my possession his two trunks of papers (amongst which is said to be his travels to the pacific ocean) and probably some Vouchers for expenditures of Public Money for a Bill which he said had been protested by the Secy. Of War, and of which act to his death, he repeatedly complained. I have also in my Care his Rifle, Silver watch, Brace of Pistols, dirk & tomahawk: one of the Governors horses was lost in the wilderness which I will endeavour to regain, the other I have sent on by his servant who expressed a desire to go to the governors Mothers & to Montic[e]llo: I have furnished him with fifteen Dollars to Defray his expenses to Charlottsville; Some days previous to the Governors death he requested of me in case any accident happened to him, to send his trunks with the papers therein to the President, but I think it very probable he meant to you. I wish to be informed what arrangements may be considered best in sending on his trunks &c. I have the honor to be with great respect Yr. Ob. Sert.

James Neelly

U.S. agent to the Chickasaw Nation

The Governor left two of his trunks in the care of Gilbert C. Russell, commanding officer, & was to write to him from Nashville what to do with them.

After Lewis’s death, Thomas Freeman, a close associate of General Wilkinson, brought Lewis’s possessions to Washington. In 1798, Freeman was fired from his assistant surveyor’s job by Andrew Ellicott, who surveyed the boundary line between Spanish Florida and U. S. Territory. Ellicott called Freeman “An idle, lying, troublesome, discontented, mischief-making man.” (Google books: Andrew Ellicott: His Life and Letters by Catherine Van Cortlandt Matthews (1908), p. 160) Subsequently Freeman was employed by Wilkinson. He was the leader of the Freeman-Custis Expedition which explored the Red River in 1806.

Isaac A. Coles was Jefferson’s last private secretary, and stayed on in the capacity under President James Madison. Note that among Lewis’s papers and journals, there was a bundle of papers on the lead mines to be delivered to President Madison: “P. U. S. One do. papers relative to the Mines.” (P. U. S. is President of the United States; “do” means ditto, or in this case “bundle.”) Did these papers reach the President? See the next entry, stating they arrived “badly assorted” when Cole took possession of them, and that he had to sort them into bundles again, with no mention of their contents.

[23 November 1809]

Memorandum of Articles Contained in two Trunks the property of Governor Lewis of Upper Louisiana Left in care of William C. Anderson Near Nashville Tennessee and taken charge by Thomas Freeman to be safe Conveyed to Washington City—Nashville 23rd Novr. 1809.

Taken in presence of Captn. Boote U. States Army—Captn. Brahan—Thomas Freeman & Wm. C. Anderson

N. Those articles marked in the Memorandum with a Star are left in a square black Trunk (the property of Govr. Lewis) in care of Wm. C. Anderson—the trunk not being of convenient shape & size for Packing.

Thos. Freeman

Washington Jany. 10. 1810

The bundles of Papers referred to in the above memorandum were so badly assorted, that no idea could be given them by any terms of general description. Many of the bundles containing at once, Papers of a public nature—Papers intirely private, some important & some otherwise, with accts. Receipts. &c. They were all carefully looked over, & put up in separate bundles. Every thing public has been given to the President or proper dept. Every thing relating to the expedition to Genl. Clarke, & all that remained has been sent to Mr. Jefferson to be delivered to Mr. Meriwether, to the care of Mr. Geo. Jefferson the following articles, viz.

| In a Small Trunk contained in the larger one | In the large Trunk a Pistol case—containing a Pocket Pistol—3 Knives &c. &c. |

| 1. Broadcloth Coat 2. Summer Do. 5. Waistcoats 1. Pair black Silk Breeches 4. Handkerchiefs |

8 Tin Canisters containing a variety of small articles of little value. |

| 3. Old flannel________. | A Sword, Tomahawk, Pike Blade & part of the Handle |

| A very small Trunk | |

| I. A. Coles | |

| [In margin] N. B. The trunk will be sent by the first vessel to Richmond, addressed to Wm. Meriwether to the care of Rob. Gordon mercht. of that place. I. A. C. | |

William Clark and his family traveled from St. Louis to the East Coast a few weeks after Lewis’s departure. They visited his brother Jonathan and other family members in Louisville, Kentucky and then went on to Fincastle, Virginia, where Julia and their 10 month old son Meriwether Lewis Clark stayed with her parents while Clark continued onto Washington.

In these three letters to Jonathan, we have almost the only reactions to Lewis’s death that William Clark ever committed to paper. In assembling these documents for publication, I realized that the letters Clark received from Captain Russell (referred to in his letter of November 26th; document 9) were almost certainly other forgeries created by Wilkinson.

Compare their reported contents with the following two letters that we know were written by Captain Russell in January, 1810 to Thomas Jefferson (documents 10-12) and the known forgery (document 15). In the authentic letters written by Russell there is no mention of attempted suicide before Lewis arrived at Fort Pickering; no “15 days in a state of derangement,” and no second will. The 1811 forgery declares there were two attempted suicides, but backs off from the claim of 15 days in a state of mental derangement.

The “letters from Captain Russell” Clark received were well crafted, because the mention of a second will made at Chickasaw Bluffs—perhaps said to be assigning the expedition papers to Clark—would seem logical and give credibility to the other statements. Though Clark searched diligently for a second will, it was never found. It almost certainly never existed. The “letters from Captain Russell” have also never been found.

The letter that Lewis wrote to Clark from New Madrid—that Clark was anxious to obtain from his brother—may have concerned the disposition of the expedition papers. Lewis wrote his will of record at New Madrid, Missouri on September 9, 1809 while en route to Fort Pickering. He was ill from malarial fevers, and rested a few days before continuing to travel. He wrote the will in his memorandum book, a small notebook, leaving everything to his mother, and had it witnessed.

These letters are reprinted with the permission of the Filson Historical Society of Louisville, Kentucky. They are from the collection of letters featured in, Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark, by James J. Holmberg (Yale University Press, 2002).

Lexington Octr. 30 1809

Dear Brother

We arrived here this evening all in the Same State of health we were when we parted with you, but not in the Same State of mind, I have herd of the Certainty of the death of Govr. Lewis which givs us much uneasiness. I have wrote to judge Overton of Nashville about his papers,—[I] have Some expctation of their falling into the Care of the Indian agent who is Said to have Come on imediately after his death &c.—I wish much to get the letter I receved of Govr. Lewis from N. madrid, which you Saw it will be of great Service to me. prey Send it to Fincastle as Soon as possible, I wish I had Some conversation with our about our Book. [and] the plans of [the] Govr. write me to fincastle if you please. we Shall Set out at Sun rise tomorrow and proced on Slowly—

our love to Sister & nany &

acup [it for] your Self [also]

Wm Clark

Julia requst John to bring on 12 pockons* for her & more if Convenent.

* Holmberg says that “pockons” are puccoons. Puccoon, or bloodroot, was a plant used both as a red dye and as a medicinal herb. Modern research shows that it has many important disease fighting constituents.

Beens [Bean] Station Wednesday 8th oct. [Nov.] 1809.

Dear Brother,

We arrived here this evening much fatigued, all quit [e] as well as when we parted with you. Lewis has a verry bad Cobld which does not decrease. The leathers which Support be [the] body of our Carrage broke on the way which detained us half a day, and the rain of last Friday was So constant and Cold that we lay by at Rickastle that day which is every [crossed out] all the detention we have had—The roads are verry bad thro’ the wilderness and more perticularly on the Turn pike of Clinch mountain, we have been all day Comeing 16 miles, over what they Call a turnpiek road, whor [for] which pleasent traveling I payed 162 ½ cents—

You have heard of that unfortunate end of Govr. Lewis and probably more than I have heard. I was in hopes of hearing more perticular [s] at this place, but have not—I wrote from Lexington to Wm. P. Anderson, to Send the Govrs/ paipers to me if they were yet in his aprt of the Conntry—

I am at a loss to know what to be at his death is a turble Stroke to me, in every repsect. I wish I could talk a little with you just now.

John Allen talked a little to me about filling his [Lewis’s] place, when at Frankfort and injoined it on me to write him on the Subject which I must do tomorrow, and what must I say?—to have a green pompous new englandr* imedieately over my head will not do for me—!—

We Shall leave this in the morning and proceed on without loss of time.

Julia joins me in love to all and beleve me to be yr. Afft. Bro.

Wm Clark

* Clark is referring to William Eustis, the Secretary of War who was denying payment of expenses to government officials. Eustis was forced to resign in 1813.

Colonel Hancocks November 26 1809

Dear Brother,

We arrived her on the 22nd. on a Cold and Snowey day without any material accidents. Col. H. met us about forty miles from this and Came down with us and on our arrival and Sense much job have been apperent in the Countenacs of all, Lewis is much broke out in Sores, but Continues helthy otherwise.

I expect to leave this [place] for washington on Sunday morning I have delayed this week expectig to receive Govr. Lewis papers by Mr. Whitesids, a Senator from Tennessee, whome I am in formed by Mr. W. P. Anderson, will take Charge of thoese papers for me and bring them on—I have just receved letters from Capt. Russell who Commands at the Chickasaw Bluffs that Govr. Lewis was there detaind by him 15 days in a State of Derangement most of the time and that he had attempted to kill himself before he got there—his Servent reports that [ ] “on his way to nashvill, he would frequently “Conceipt [conceive] that he herd me Comeing on, and Said that he was certain [I would] over take him, that I had herd of his Situation and would Come to his releaf”—[ ] Capt. rusell Sais [ ] he made his will at the Bluffs and left Wm. Merrewether & myself Execeters and derected that I Should disposes of his papers &c. as I wished—pore fellow, what a number of Conjecturral reports we hear mostly unfavourable to him. I have to Contredict maney of them—I do not know what I Shall do about the publication of the Book, it will require funds which I have not at present. perhaps I may precure them—I have just herd that one of my Bills drawn on the Secty. of War for the quarterly pay of Docr. Robinson a Sub Indiana Agent of the Osage apt. by Govr. Lewis have been protested for $160 which alarms me verry much. if this Should be the Only one I shall be easy, as I am convenced that explanation will Cause the Secty. to pay this Bill which was drawn previous to the late arragemt. made by the Secty. in respect to those appts.—

Maj. Preston Doct. Floyd and maney others in this quarter have got the Louisiana fever verry hot and will vesit that Country next Spring—Crops are fine about here but below the Blue ridge I am told are very bad—I hope to See John [Hite Clark] this week before I Set out, as he had expectations of getting here about this time—The Small Change [purse] which I thought had been left at your house was found Since we Came here among our Clothes—

Julia joins me in love to yourself Sister nancy Bro Edmund & Isaac acpt of our preyer for the helth and hapiness of you all

Yr

Wm Clark

(Captain Russell was promoted to Major on May 9, 1809. For unknown reasons, he continued to be addressed and to refer to himself as Captain during this time.)

Captain Gilbert Christian Russell of the Fifth Infantry was the commander of Fort Pickering. Some of his bills for government expenses had also been refused and he wanted to go with Lewis to Washington on the same mission—to straighten out matters with government bureacrats. After Lewis recovered his health, he waited 6 to 8 days for Russell to receive permission from General James Wilkinson to travel with him; but permission was denied and instead James Neelly accompanied Lewis on his fateful journey.

Captain Russell must have made his request to Wilkinson for permission to travel prior to Lewis’s arrival, as the General was in New Orleans in September. It is 640 river miles from Memphis to New Orleans on today’s river. A post rider made at most 50 miles a day, indicating that 3-4 weeks was a more likely estimate combining river and overland travel. Governor Lewis’s travel down river was a subject of news stories, and Russell may well have anticipated his arrival, or his own request may have simply been a coincidence.

These letters indicate that Russell was careful of facts, and if Lewis had attempted suicide, been in a state of mental derangement, or written a second will at Fort Pickering, he would have reported it to Thomas Jefferson. In the letter of January 31, 1810 Russell condemns the character of James Neelly and writes that, if instead, he had been allowed to accompany Lewis, or send one of his own men with him, Lewis’s death would not have taken place. He writes:

“Unfortunately for him this arrangement did not take place, or I hesitate not to say he would this day be living.”

The pistols were never recovered from Neelly, despite the attempts of Meriwether Lewis’s step brother, John Marks, to retrieve them when he visited Tennessee in 1811. An undated note by John Marks in the Lewis-Marks Collection at the University of Virginia Library states that Major James Neely had Meriwether Lewis’s gold watch and pistols.

Russell believed the suicide story, and blamed Neelly for encouraging Lewis’s drinking. He also believed that Lewis’s servant, Pernier may have been involved, from something he has heard. Perhaps he heard the story of Pernier dressing in Lewis’s clothes, as reported in document 16.

Lewis was not a drinker. Frederick Bates, the Secretary of the Territory—a jealous and spiteful man who quarreled with Lewis—never accused him of either alcoholism or depression. Lewis had suffered from malaria for years. He was worried and being escorted by a man whom he most likely did not trust, as the following analysis of the memorandum indicates.

The memorandum on the care of his trunks, a package and a case, and the trunk of Captain House, is an important one that has never received the attention it deserves (# 11, pp 247-48).

“M. Lewis would thank Capt. R. to be particular to whom he confides these trunks &c. a Mr. Cabboni of St. Louis may be expected to pass this place in the course of the next month, to him they may be safely confided.”

Lewis would thank Captain Russell to only give these trunks &c. to either Jean-Pierre Cabanne, a wealthy St. Louis fur trader to be delivered to Lewis’s friend, William Carr, the United States Land Agent; or to await further instructions by letter from Lewis after he has arrived at Nashville.

Instead, Captain Russell responds to a verbal message delivered by an unnamed messenger, after Lewis has left the fort to “keep them until I shall hear from him again.” It was an early foreshadowing of the death of Lewis. Someone wanted to examine the contents of those trunks. It appears likely there was incriminating evidence in them. Another implication is that Lewis was uncertain as to whether he would reach Nashville alive. If he did, he would write with further instructions. The obvious arrangement would be to send them to Washington.

Benjamin Wilkinson, the General’s nephew, was at Fort Pickering on September 29th, and he took possession of Captain House’s trunks. He was going to New Orleams to travel by ship to Baltimore. He died on board ship in February, 1810 of an unknown cause. Captain House was in Nashville, where he wrote his letter of September 28th to Bates (# 3).

Fort Pickering, Chickesaw Bluffs,

January 4th 1810

Sir,

Conceiving it a duty incumbant upon me to give the friends of the late Meriwether Lewis such information relative to his arrival here, his stay and departure, and also of his pecuniary matters as came within my knowledge which they otherwise might not obtain, and presuming that as you were once his patron, you still remain’d his friend, I beg leave to communicate it to you and thro’ you to his mother and such other of his friends as may be interested.

He came here on the 15th September last from whence he set off intending to go to Washington by way of New Orleans. His situation that rendered it necessary that he should be stoped until he would recover, which I done & in a short time by proper attention a change was perceptible and in about six days he was perfectly restored in every respect & able to travel. Being placed then myself in a similar situation with him by having Bills protested to a considerable amount I had made application to the General & expected leave of absence every day to go to Washington on the same business with Governor Lewis. In consequence of which he waited six or eight days expecting I would go on with him, but in this we were disappointed & he set off with a Major Neely who was going to Nashville.

At the request of Governor Lewis I enclosed the land warrant granted to him in consideration of his services to the Pacific Ocean to Bowling Robinson Esq Sec’y of the T’y [Treasury] of Orleans with instructions to dispose of it at any price above two dollars per acre & to lodge the money in the Bank of the United States or any of the branch banks subject to his order.

He left me with two Trunks a case and a bundle which will now remain here subject at any time subject to your order or that of his legal representatives. Enclosed is his memo respecting them but before the Boat in which he directed they might be sent got to this place I rec’d a verbal message from him after he left here to keep them until I should hear from him again.

He set off with two Trunks which contain’d all his papers relative to his expedition to the Pacific Ocean, Gen’l Clark’s Land Warrant, a Port-Folio, pocket Book, and Note Book together with many other papers of both a public & private nature, two horses, two saddles & bridles, a Rifle, gun, pistols, pipe, tomahawk & dirks, all ellegant & perhaps about two hundred & twenty dollars, of which $99.58 was a Treasury Check on the U. S. branch Bank of Orleans endorsed by me. The horses, one saddle, and the check I let him have. Where or what has become of his effects I do not know but presume they must be in the care of Major Neely near Nashville.

As an individual I verry much regret the untimely death of Governor Lewis whose loss will be great to his country & surely felt by his friends. When he left I felt much satisfaction for indeed I tho’t I had also been the means of preserving the life of this valuable man, and as it has turned out I shall have the consolation that I discharged those obligations towards him that man is bound to do to his fellows.

It is probable that I shall go to the City of Washington in a few weeks also. I shall give you a call and give any further information you may require that has come within my knowledge. Having had the pleasure of knowing Mr. Wm. Randolph, I pray you to tender my respects to him.

I remain Sir with the utmost veneration and respect your Ob’t Servant.

Gilbert C. Russell

Thomas Jefferson Esq.

Fort Pickering, Chickesaw Bluffs,

September 28th 1809

Capt. Russell will much oblige his friend Meriwether Lewis by forwarding to the care of William Brown Collector of the port of New Orleans, a Trunk belonging to Capt. James House addressed to McDonald and Ridgely Merchants in Baltimore. Mr. Brown will be requested to forward this trunk to its place of destination. Capt. R. will also send two trunks a package and a case addressed to Mr. William C. Carr of St. Louis unless otherwise instructed by M. L. by letter from Nashville.

M. Lewis would thank Capt. R. to be particular to whom he confides these trunks &c. a Mr. Cabboni of St. Louis may be expected to pass this place in the course of the next month, to him they may be safely confided.

[On reverse side of Lewis Memo to Russell]

Memorandum

Sent Capt. Hous’s Trunk by Benjamin Wilkinson on the 29th Sept. 1809

Russell

Gov’r Lewis left here on the morning of the 29th Sept.

Fort Pickering, Chickesaw Bluffs,

31st January 1810

Sir,

I have lately been informed that James Neely the Agt. to the Chickasaws with whom Govr Lewis set off from this place has detained his pistols & perhaps some other of his effects for some claim he pretends to have upon his estate. He can have no just claim for any thing more than the expenses of his interment unless he makes a charge for packing his two Trunks from the nation. And for that he cannot have the audacity to make a charge after tendering the use of a loose horse or two which he said he had to take from the nation & also the aid of his servant. He seem’d happy to have it in his power to serve the Govr & but for making the offer which I accepted I should have employ’d the man who packed the trunks to the Nation to have them taken to Nashville & accompany the Govr. Unfortunately for him this arrangement did not take place, or I hesitate not to say he would this day be living. The fact is which you may yet be ignorant of that his untimely death may be attributed solely to the free use of liquor which he acknowledged verry candidly to me after he recovered & expressed a firm determination to never drink any more spirits or use snuff again both of which I deprived him of for several days & confined him to claret & a little white wine. But after leaving this place by some means or other his resolution left him & this Agt. being extremely fond of liquor, instead of preventing the Govr from drinking or keeping him under any restraint advised him to it & from every thing I can learn gave the man every chance to seek an opportunity to destroy himself. Also from the statement of Grinder’s wife where he killed himself I cannot help to believe that Purney was rather aiding & abeting in the murder than otherwise.

This Neely also says he lent the Govr money which cannot be so as he had none himself & the Govr had more than one hund. $ in notes & specie besides a check I let him have of 99.58 none of which it is said could be found. I have wrote to the Cashier of the branch bank of Orleans as whom the check was drawn in favor of myself or order to stop payt. when presented. I have this day authorized a gentleman to pay the pretended claim of Neely & take the pistols which will be held sacred to the order of any of the friends of M. Lewis free from encumbrance.

I am Sir with great respect your Obt Servt.

Gilbert C. Russell

Tho. Jefferson Esq.

Julian Boyd, the editor of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, found several letters to Thomas Jefferson regarding Meriwether Lewis’s servant, John Pernier’s request for the back pay of $240 owed him by the Lewis Estate; and the subsequent attempts by his friend John Christopher Sueverman to claim the money after Pernier’s death. Dr. Boyd passed them on to Donald Jackson who published them in an article entitled “On the Death of Meriwether Lewis’s Servant” in 1964. Jackson discovered that Pernier had been employed as a servant in the White House by Thomas Jefferson for parts of 1804 and 1805, and found a pay record for Sueverman in 1803.

Jefferson in a letter supporting Sueverman’s claim wrote:

“Suverman was a servant of mine, a very honest man. He has since become blind, and gets his living by keeping a few groceries which he buys and sells from hand to mouth. He is miserably poor.” So this letter was not written by Sueverman, who was blind, but was written for him. William Clark, the administrator of Lewis’s estate, did not think Sueverman’s claim on Pernier’s estate was justified and refused to pay it.

John Pernier was a free mulatto, of French and African American ancestry. He accompanied Lewis to St. Louis in 1807 and served as his personal valet and servant. He was present at the scene of Meriwether’s Lewis death. Lucy Marks, Lewis’s mother, believed Pernier had participated in the murder of her son. Perhaps, like Russell, she may have been reacting to the story of Pernier dressed in Lewis’s clothes. (See document 14, p. 251). Reprinted from The William and Mary Quarterly (3rd Ser., 21:3, July, 1964, pp. 445–448) by permission of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture.

City of Washington 5th May 1810 (13)

Sir,

Respectfully I wish to inform you of the Unhappy exit of Mr. Pirny. He boarded, and lodged, with us ever since his return from the Western Country. The principal part of the time he has been confined by Sickness, I believe ariseing from uneasyness of mind, not having recd. anything for his late services to Govr. Lewis. He was wretchedly poor and destitute. Every service in our power was rendered him to make him confortable, not doubting but the moment he had it in his power he would thankfully and honestly pay us.

Last Week the poor Man appeared considerably better, I believe in some respects contrary to his wishes, for unfortunately Saturday last he procured himself a quantity of Laudenam. On Sunday Morning under the pretence of not being so well went upstairs to lay on the bed, in which situation he was found dead, with the bottle by his Side that had contained the Laudanam. Our distress was great but it was to late to render him any assistance. He was buried neat and decent the very next day which in addition to his former expences, fall very heavy upon us, whose circumstances you are well with acquainted with, cannot bear it without suffering considerably, and hope you will be so oblidgeing as [to] assist us as Soon as it is possible to recover anything on behalf of the poor Man.

I am with great Respect Sir your Obedt. H’ble Servt.

John Christoper Sueverman

The great bird artist Alexander Wilson was a personal friend of Lewis’s. When Lewis came to Philadelphia in 1807, he gave Wilson the bird specimens he had collected on the expedition, and drawings of these birds were included in the second volume of Wilson’s American Ornithology.

Wilson was as hardy and tough as Lewis; he was accustomed to traveling hundreds of miles on foot and horseback, in pursuit of both birds and of subscribers to his multi-volume publication, which eventually reached nine volumes. When he traveled south in the spring of 1810, he visited Grinder’s Inn on May 6, 1810.

(This account describing his visit to Lewis’s gravesite is taken from a long letter recording his travels on the Natchez Trace.)

Natchez, Mississippi Territory (14)

18 May 1810

To Alexander Lawson,

…Next morning (Sunday) I rode six miles to a man’s of the name of Grinder, where our poor friend Lewis perished. In the same room where he expired, I took down from Mrs. Grinder the particulars of that melancholy event, which affected me extremely. This house or cabin is seventy-two miles from Nashville, and is the last white man’s as you enter the Indian country. Governor Lewis, she said, came hither about sunset, alone, and inquired if he could stay for the night; and, alighting, brought the saddle into the house. He was dressed in a loose gown, white, striped with blue. On being asked if he came alone, he replied that there were two servants behind, who would soon be up. He called for some spirits, and drank a very little. When the servants arrived, one of whom was a negro, he inquired for his powder, saying he was sure he had some powder in a canister. The servant gave no distinct reply, and Lewis, in the meanwhile, walked backwards and forwards before the door talking to himself. Sometimes, she said, he would seem as if he were walking up to her; and would suddenly wheel round, and walk back as fast as he could. Supper being ready he sat down, but had eaten only a few mouthfuls when he started up, speaking to himself in a violent manner. At these times, she says, she observed his face to flush as if it had come on him in a fit. He lighted his pipe, and drawing a chair to the door sat down, saying to Mrs. Grinder, in a kind tone of voice, “Madame this is a very pleasant evening.” He smoked for some time, but quitted his seat and traversed the yard as before. He again sat down to his pipe, seemed again composed, and casting his eyes wistfully towards the west, observed what a sweet evening it was. Mrs. Grinder was preparing a bed for him; but he said he would sleep on the floor, and desired the servant to bring the bearskins and buffalo robe, which were immediately spread out for him; and it being now dusk, the woman went off to the kitchen, and the two men to the barn, which stands about two hundred yards off. The kitchen is only a few paces from the room where Lewis was, and the woman being considerably alarmed by the behaviour of her guest could not sleep, but listened to him walking backwards and forwards, she thinks, for several hours, and talking aloud, as she said, “like a lawyer.” She then heard the report of a pistol, and something fall heavily on the floor, and the words—”O Lord!” Immediately afterwards she heard another pistol, and in a few minutes she heard him at her door calling out “O madam! Give me some water, and heal my wounds.” The logs being open, and unplastered, she saw him stagger back and fall against a stump that stands between the kitchen and room. He crawled for some distance, and raised himself by the side of a tree, where he sat about a minute. He once more got to the room; afterwards he came to the kitchen-door, but did not speak; she then heard him scraping the bucket with a gourd for water; but it soon appeared that this cooling element was denied the dying man! As soon as the day broke and not before—the terror of the woman having permitted him to remain for two hours in this most deplorable situation—she sent two of her children to the barn, her husband not being at home, to bring the servants; and on going in they found him lying on the bed;. he uncovered his side, and showed them where the bullet had entered; a piece of the forehead had blown off, and had exposed the brains, without having bled much. He begged they would take his rifle and blow out his brains, and he would give them all the money he had in his trunk. He often said, “I am no coward; but I am so strong, so hard to die.” He begged the servant not to be afraid of him, for that he would not hurt him. He expired in about two hours, or just as the sun rose above the trees. He lies buried close by the common path, with a few loose rails thrown over his grave. I gave Grinder money to put a post fence round it to shelter it from the hogs, and from the wolves; and he gave me his written promise he would do it. I left this place in a very melancholy mood, which was not much allayed by the prospect of the gloomy and savage wilderness which I was just entering alone….

Alexander Wilson

This document was found in the papers of Colonel Jonathan Williams at the Lilly Library, University of Indiana. The two document examiners, Gerald B. Richards and Duayne Dillon agree that it was neither written nor signed by either of the two men whose names are on the document—Gilbert C. Russell and Jonathan Williams. (See pp. 126-140 and 164-175.)

It was first published by Donald Jackson in his Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1962. Because it was published without the two letters written by Captain Russell to President Jefferson in January, 1810, it’s authenticity was never questioned by scholars. Though Vardis Fisher in his 1962 book, Suicide or Murder?: The Strange Death of Meriwether Lewis wrote:

But for us there is something strangely unlike Russell in his manner of writing this account of Lewis’s death. In his two letters to Jefferson his friendship and his feeling for Lewis shone through at every point. Here he says that Lewis killed himself in ‘the most cool desperate and Barbarian-like manner’—strange words from an army man whose profession was killing with guns.

Upon my [Kira Gale] discovery of a second document in the Williams Archives in the same handwriting—a 12 page court brief for Wilkinson, supposedly signed by him—this new document was examined by Jerry Richards in December, 2008. He has certified that both documents were written by an unknown person. (See appendix and illustrations on p. 256.) It is likely they were both dictated to a subordinate by General Wilkinson. The court brief was simply Wilkinson’s defense of his conduct and career in preparation for the court martial he was undergoing. The language and the references of the 1811 “Russell statement” bear little relationship to Russell’s letters of January 4 and January 31, 1810. (See discussion on pp. 227–230 and 243-246; and documents 10-12 on pp. 243–247.)

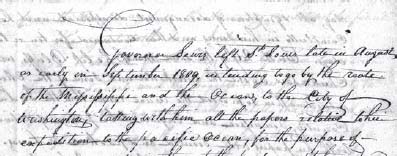

[Russell Statement, 26 November 1811] (15)

Governor Lewis left St. Louis late in August, or early in September 1809, intending to go by the route of the Mississippi and the Ocean, to the City of Washington, taking with him all the papers relative to his expedition to the pacific Ocean, for the purpose of preparing and putting them to the press, and to have some drafts paid which had been drawn by him on the Government and protested. On the morning of the 15th of September, the Boat in which he was a passenger landed him at Fort pickering in a state of mental derangement, which appeared to have been produced as much by indisposition as other causes. The Subscriber being then the Commanding Officer of the Fort on discovering from the crew that he had made two attempts to Kill himself, in one of which he had nearly succeeded, resolved at once to take possession of him and his papers, and detain them there untill he recovered, or some friend might arrive in whose hands he could depart in Safety.

In this condition he continued without any material change for about five days, during which time the most proper and efficatious means that could be devised to restore him was administered, and on the sixth or seventh day all symptoms of derangement disappeared and he was completely in his senses and thus continued for ten or twelve days. On the 29th of the same month he left Bluffs, with the Chickasaw agent the interpreter and some of the Chiefs, intending to proceed the usual route thro’ the Indian Country, Tennissee and Virginia to his place of distination, with his papers well secured and packed on horses. By much severe depletion during his illness he had been considerably reduced and debilitated, from which he had not entirely recovered when he set off, and the weather in that country being yet excessively hot and the exercise of traveling too severe for him; in three or four days he was again affected with the same mental disease. He had no person with him who could manage or controul him in his propensities and he daily grew worse untill he arrived at the house of a Mr. Grinder within the Jurisdiction of Tennissee and only Seventy miles from Nashville, where in the apprehension of being destroyed by enemies which had no existence but in his wild immagination, he destroyed himself, in the most cool desperate and Barbarian-like manner, having been left in the house intirely to himself. The night preceeding this one of his Horses and one of the Chickasaw agents with whom he was traveling Strayed off from the Camp and in the Morning could not be found. The agent with some of the Indians stayed to search for the horses, and Governor Lewis with their two servants and the baggage horses proceeded to Mr. Grinders where he was to halt untill the agent got up.

After he arrived there and refreshed himself with a little Meal & drink he went to bed in a cabin by himself and ordered the servants to go to the stables and take care of the Horses, least they might loose some that night; Some time in the night he got his pistols which he loaded, after every body had retired in a Separate Building and discharged one against his forehead not making much effect—the ball not penetrating the skull but only making a furrow over it. He then discharged the other against his breast where the ball entered and passing downward thro’ his body came out low down near his back bone. After some time he got up and went to the house where Mrs. Grinder and her children were lying and asked for water, but her husband being absent and having heard the report of the pistols she was greatly allarmed and made him no answer. He then in returning got his razors from a port folio which happened to contain them and Seting up in his bed was found about day light, by one of the Servants, busily engaged in cutting himself from head to foot. He again beged for water, and so soon as he drank, he lay down and died with the declaration to the Boy that he had killed himself to deprive his enemies of the pleasure and honor of doing it. His death was greatly lamented. And that a fame so dearly earned as his should finally be clouded by such an act of desperation was to his friends still greater cause of regret.

(Signed) Gilbert Russell

The above was received by me from Major Gilbert Russell of the [blank] Regiment of Infantry U.S. on Tuesday the 26th of November 1811 at Fredericktown in Maryland.

J. Williams

Novemberr 26, 1811 Statement—Some old documents experience bleed through from the reverse side of the page as seen here. The contrast has been increased so that the distinctive long “t bars” are seen here.

An undated brief of 12 pages handwritten and bearing the name of James Wilkinson as its author regarding his court martial (circa October, 1811). However it is not the handwriting of General Wilkinson.

These three excerpts are taken from a biographical essay of Meriwether Lewis which Thomas Jefferson was asked to provide for the publication of the Lewis and Clark Journals in 1814. Paul Allen was the publisher. The former president wrote at length about Lewis’s ancestors; his own early attempts to send someone to explore the Pacific Northwest; the two years Lewis spent livng and working at the White House as Jefferson’s private secretary; and the expedition itself. The passages related to Lewis’s character, mental depression, and praise for his accomplishments are reprinted here.

Monticello, Aug. 18, 1813 (16)

Sir

(first excerpt)

… Captain Lewis who had then been near two years with me as private secretary, immediately renewed his sollicitations to have the direction of the party. I had now had opportunities of knowing him intimately. Of courage undaunted, possessing a firmness & perseverance of purpose which nothing but impossibilities could divert from it’s direction, careful as a father committed to his charge, yet steady in the maintenance of discipline & order, intimate with the Indian character, customs & principles, habituated to the hunting life, guarded by exact observation of the vegetables & animals of his own country, against losing time in the description of objects already possessed, honest, disinterested, liberal, of sound understanding and a fidelity to truth so scrupulous that whatever he should report would be as certain as if seen by ourselves, with all these qualifications as if selected and implanted by nature in one body, for this express purpose, I could have no hesitation in confiding the enterprise to him. To fill up the measure desired, he wanted nothing but a greater familiarity with the technical language of the natural sciences, and readiness in the astronomical observations necessary for the geography of his route.

… It was the middle of Feb. 1807 before Capt. Lewis with his companion Clarke reached the city of Washington where Congress was then in session. That body granted to the two chiefs and their followers, the donation of lands which they had been encouraged to expect in reward of their toils & dangers. Capt. Lewis was soon after appointed Governor of Louisiana, and Capt. Clarke a General of it’s militia and agent of the U. S. for Indian affairs in that department.

A considerable time intervened before the Governor’s arrival at St. Louis. He found the territory distracted by feuds & contentions among the officers of the government, & the people themselves divided by these into factions & parties. He determined at once, to take no side with either; but to use every endeavor to conciliate & harmonize them. The even-handed justice he administered to all soon established a respect for his person & authority, and perseverance & time wore down animosities and reunited the citizens again into one family.

Governor Lewis had from early life been subjet to hypochondrial affections. It was a constitutional disposition in all the nearer branches of the family of his name & was more immediately inherited by him from his father. They had not however been so strong as to give uneasiness to his family. While he had lived with me in Washington, I observed at times sensible depressions of mind, but not knowing their constitutional source, I estimated their course by what I had seen in the family. During his Western expedition the constant exertion which that required of all the faculties of body & mind, suspended these distressing affections; but after his establishment at St. Louis in sedentary occupations they returned upon him with redoubled vigor, and began seriously to alarm his friends. He was in a porxysm of one of these when he affairs rendered it necessary for him to go to Washington.

(third excerpt)

…About 3 oclock in the night he did the deed which plunged his friends into affliction and deprived his country of one of her most valued citizens whose valour & intelligence would have been now imployed in avenging the wrongs of his country and in emulated by land the splendid deeds which have honored her arms on the ocean. It lost too the nation the benefit of recieving from his own hand the Narrative now offered them of his sufferings & successes in endeavoring to extend for them the boundaries of science, and to present to their knoledge that vast & fertile country with arts, with science, with freedom & happiness.

To this mechancholy close of the life of one whom posterity will declare not to have lived in vain I have only to add that all facts I have stated are either known to myself, or communicated by his family or others whose truth I have no hesitation to make [myself] responsible; and I conclude with tendering you the assurance of my respect & consideration.

Th: Jefferson

This entry was found in A Collection of American Epitaphs and Inscriptions with Occasional Notes by Rev. Timothy Alden (1814). It relates the sad fate of Meriwether Lewis’s dog, a Newfoundland dog named Seaman. The collar has been lost to history. This is the only mention that has ever been found, and there is no reason to doubt it. Reverend Alden founded Allegheny College in western Pennsylvania. James Holmberg of the Filson Historical Society located this reference.

Entry 916

“The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacifick ocean through the interior of the continent of North America.”

The foregoing was copied from the collar, in the Alexandria Museum, which the late gov. Lewis’s dog wore after his return from the western coast of America. The fidelity and attachment of this animal were remarkable. After the melancholy exit of gov. Lewis, his dog would not depart for a moment from his lifeless remains; and when they were deposited in the earth no gentle means could draw him from the spot of interment. He refused to take every kind of food, which was offered him, and actually pined away and died with grief upon his master’s grave!

Robert Evans Griner/Grinder died in 1827. It is thought that after his death, Priscilla Grinder felt free to tell another version of the story of Lewis’s death, which found its way into this newspaper account in 1845.

The family name is Griner, but they are more commonly known as Grinder. After Lewis’s death it is said they came into a large sum of money and moved to Hickman County, TN.

Despite the local tradition of Grinder murdering Lewis, it appears likely that he was part of a wider conspiracy. (The document is found in the Draper Manuscript Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society, 29 CC 33.)

DISPATCH

New-York, February 1, 1845

Published on the first of every month by

B. H. Day and J. G. Wilson

Singular Fate of a Distinguished Man

We find in the North Arkansas, a paper published at Batesville, Ark., a communication stating some singular and not generally known facts concerning the mysterious death of Capt. George M. Lewis, one of the two persons employed by the U. S. Government to conduct the celebrated Expedition of Lewis and Clark, in exploring the region West of the Rocky Mountains. The writer is at present a teacher in the Cherokee Nation, and says that he is personally acquainted with the circumstances which he relates. The expedition, consisting of seventy or eighty persons, under the guidance of Lewis and Clark, was commenced in 1803 or 1804, and completed in about three years. The writer says the remains of Captain Lewis are “deposited in the southwest corner of Maury county, Tennessee, near Grinder’s old stand, on the Natchez trace where Lawrence, Maury, and Hickman counties corner together.” He visited the grave in 1838, found it almost concealed by brambles, without a stone or monument of any kind, and several miles from any house. An old tavern stand, known as Grinder’s, once stood near by, but was long since burned. The writer gave the following narrative of the incidents attending the death of Capt. Lewis, as he received them from Mrs. Grinder, the landlady of the house where he died in so savage a manner.

She said that Mr. Lewis was on his way to the city of Washington, accompanied by a Mr. Pyrna and a servant belonging to a Mr. Neely. One evening, a little before sundown, Mr. Lewis called at her house and asked for lodgings. Mr. Grinder not being at home, she hesitated to take him in. Mr. Lewis informed her two other men would be along presently, who also wished to spend the night at her house, and as they were all civil men, he did not think there would be any impropriety in her giving them accommodations for the night. Mr. Lewis dismounted, fastened his horses, took a seat by the side of the house, and appeared quite sociable. In a few minutes Mr. Pyrna and the servants rode up, and seeing Mr. Lewis, they also dismounted and put up their horses. About dark two or three other men rode up and called for lodging. Mr. Lewis immediately drew a brace of pistols, stepped towards them and challenged them to fight a duel. They not liking this salutation, rode on to the next house, five miles. This alarmed Mrs. Grinder. Supper, however, was ready in a few minutes. Mr. Lewis ate but little. He would stop eating, and sit as if in a deep study, and several times exclaimed, “If they do prove any thing on me, they will have to do it by letter.” Supper being over, and Mrs. Grinder seeing that Mr. Lewis was mentally deranged, requested Mr. Pyrna to get his pistols from him. Mr. P. replied, “He has no ammunition, and if he does any mischief it will be to himself, and not to you or any body else.” In a short time all retired to bed; the travellers in one room as Mrs. G. thought, and she and her children in another.

Two or three hours before day, Mrs. G. was alarmed by the report of a pistol, and quickly after two other reports, in the room where the travellers were. At the report of the third, she heard some one fall and exclaim, “O Lord! Congress relieve me!” In a few minutes she heard some person at the door of the room where she lay. She inquired,, “Who is there?” Mr. Lewis spoke and said, “Dear Madam, be so good as to give me a little water.” Being afraid to open the door, she did not give him any. Presently she heard him fall, and soon after, looking through a crack in the wall, she saw him scrambling across the road on his hands and knees.

After daylight Mr. Pyrna and the servant made their appearance, and it appeared they had not slept in the house, but in the stable. Mr. P. had on the clothes Mr. L. wore when they came to Mrs. Grinder’s the evening before, and Mr. L.’s gold watch in his pocket. Mrs. G. asked what he was doing with Mr. L.’s clothes on; Mr. P. replied “He gave them to me.” Mr. P. and the servant then searched for Mr. L., found him and brought him to the house, and though he had on a full suit of clothes, they were old and tattered, and not the same as he had on the evening before, and though Mr. P. had said that Lewis had no ammunition, Mrs. G. found several balls and a considerable quantity of powder scattered over the floor of the room occupied by Lewis; also a canister with several pounds in it…

In 1848 the State of Tennessee appropriated $500 to erect a monument to Meriwether Lewis. In the process of identifying his gravesite, the remains of Meriwether Lewis were exhumed. Dr. Samuel B. Moore was a member of the monument committee who examined the “upper portion of the skeleton.” Later in the report, the committee states, that though it was commonly believed that Meriwether Lewis committed suicide, “it seems to be more probable that he died by the hands of an assassin.”

***********

To the General Assembly of the State of Tennessee:

By the 9th section of an act, passed at the last session of the General Assembly on this State, entitled an act to establish the County of Lewis the sum of $500 was appropriated, or so much thereof as might be necessary, to preserve the place of interment where the remains of GEN. MERIWETHER LEWIS were deposited; and the undersigned were appointed the agents of the General Assembly to carry into execution the provisions of the act, and report to the present General Assembly.

Looking upon the object to be accomplished to be one highly honorable to the State, the undersigned entered upon the duties assigned them cheerfully and with as little delay as possible. They consulted with the most eminent artists and practical mechanics as to the kind of monument to be erected, and a plan being agreed upon, they employed Mr. Lemuel W. Kirby, of Columbia, to execute it for the sum of five hundred dollars.

The entire monument is twenty and a half feet high. The design is simple but is intended to express the difficulties, successes, and violent termination of a life which was marked by bold enterprise, by manly courage and by devoted patriotism.

The base of the monument is of rough, unhewn stone, eight feet high and nine feet square where it rises to the surface of the ground. On this rests a plinth of cut stone, four feet square and eighteen inches in thickness, on which are the inscriptions given below. On this plinth stands a broken column eleven feet high, two and a half feet in diameter for the base, and a few inches smaller at the top. The top is broken to denote the violent and untimely end of a bright and glorious career. The base is composed of a species of sandstone found in the neighborhood of the grave. The plinth and shaft, or column, are made of a fine limestone, commonly known as Tennessee marble. Around the monument is erected a handsome wrought iron rail fence.

Great care was taken to identify the grave. George Nixon, Esq., an old Surveyor, had become very early acquainted with its locality. He pointed out the place; but to make assurance doubly sure the grave was re-opened and the upper portion of the skeleton examined, and such evidence found as to leave no doubt as to the place of internment. Witnesses were called and their certificate, with that of the Surveyor, prove the fact beyond dispute. The inscription upon the plinth was furnished by Professor Nathaniel Cross of the University of Nashville. It is beautiful and appropriate. It is placed on the different sides of the plinth, and is as follows:

MERIWETHER LEWIS BORN NEAR CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA, AUGUST 18, 1774 DIED OCTOBER 11, 1809; AGED 35 YEARS;

An Officer of the Regular Army - Private Secretary to President Jefferson - Commander of the Expedition To The Oregon in 1803-1806 - Governor of the Territory of Louisiana - His Melancholy Death OccurredWhere This Monument Now Stands, And Under Which Rests His Mortal Remains.

In the language of Mr. Jefferson:

“His Courage Was Undaunted; His Firmness and Perseverance Yielded To Nothing But Impossibilities; A Rigid Disciplinarian, Yet Tender As A Father To Those Committed To His Charge; Honest, Disinterested, Liberal, With A Sound Understanding, And AScrupulous Fidelity To Truth.

Immaturus Obi; Sed Tu Felicior Annos Vive Meos, Bona Republica! Vive Tuos.

ERECTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF TENNESSEE, A. D., 1848.

In the Latin diatich, many of your honorable body will no doubt recognize as the affecting epitaph on the tomb of a young wife, in which by a prosopopocia, after alluding to an immature death, she prays that her happier husband may live out her years and his own.

Immaturus pari: sed tu felicior annos.

Vive meos, conjux optime! Vive tuos.

Under the same figure, the deceased is represented in the Latin diatich as altered, after alluding to his early death, as uttering as a patriot a similar prayer, that the republic may fulfill her high destiny, and that her years may equal those of time. As the diatich now stands, the figure may be made to apply either to the whole Union, or to Tennessee, that has honored his memory by the erection of a monument.

The impression has long prevailed that under the influence of disease of body and mind - of hopes based upon long and valuable services - not merely deferred, but wholly disappointed - Governor Lewis perished by his own hands. It seems to be more probable that he died by the hands of an assassin. The place at which he was killed is even yet a lonely spot. It was then wild and solitary, and on the borders of the Indian Nation. Maj. M. L. Clark, a son of Governor Clark of Missouri; in a letter to the Rev. Mr. Cressey of Maury County says:

“Have you ever heard of the report that Gov. Lewis did not destroy his own life, but was murdered by his servant, a Frenchman, who stole his money and horses, returned to Natchez, and was never afterwards heard of? This is an important matter in connection with the erection of a monument to his memory, as it clearly removes from my mind at least, the only stigma upon the fair name I have the honor to bear.”