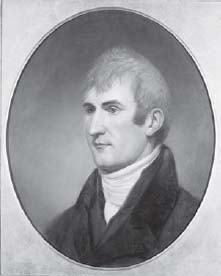

Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809)

William Clark (1770-1838)

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark portraits by Charles Willson Peale Independence National Historical Park

Stephen Ambrose made the case for Meriwether Lewis having committed suicide in Undaunted Courage, his biography of Lewis published in 1996. Because his popular book was the cornerstone of the 2004-2006 Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Commemoration, it is now a widely held belief that the famed explorer committed suicide. But through the years many historians have questioned this.

In 1988, Ambrose himself appears to have endorsed the murder theory. He wrote a foreword for a new edition of Richard Dillon’s 1965 biography, Meriwether Lewis, in which Dillon stated about Lewis’s death, “Yes it was murder.” Ambrose wrote in his foreword:

“The only reason I have not written his biography [Lewis’s] is that Richard Dillon did it first, and his is such a model biography there is no need for another one.”

Why did Ambrose use the words “Undaunted Courage” in his title and why did President Jefferson describe his friend as being “of courage undaunted … which nothing but impossibilities could divert from its direction” if indeed they thought Meriwether Lewis had committed suicide? It is a contradiction—a person commiting suicide is not “undaunted.”

The answer may be they believed that Lewis had “undaunted courage,” and that they wished to honor the memory of Meriwether Lewis as a true hero, and leave it to future historians to unravel the cause of his death. It is a mystery, and the only real answer may lie in the exhumation of the famed explorer’s remains.

THE CASE FOR THE MURDER OF MERIWETHER LEWIS is made in this last section. It incorporates the new evidence discovered in preparing this book for publication—the identification of General James Wilkinson as being associated with the forgery of the November 26, 1811 document, which is often cited as proof of Meriwether Lewis’s suicidal intentions. In the preceeding sections you have read the testimony of expert crime scene investigators and historians and examined the documetary evidence. But, if it was a case of murder—whether or not an exhumation takes place, or the evidence is conclusive—the question remains, for what reason?

The story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition will always endure as a great, exciting adventure story, but it took place against a backdrop ofpower politics that has yet to be explored. In this account of the last three years of Meriwether Lewis’s life, the world in which he lived is revealed, and a case is made for Wilkinson and others as conspirators in Lewis’s assassination.

RETURNING HOME IN THE SUMMER OF 1806, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the other members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition were bringing great news—they had explored the vast continent; held councils with over a dozen Indian tribes; and, most importantly, they had reached the mouth of the Columbia River on the Pacific Ocean coast. The official name of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was the “Corps of Volunteers for Northwestern Discovery.”

They were an elite, hand-picked, army unit of 27 soldiers and two commanding officers whose mission was to reinforce the American claim to Oregon Country. In 1792, the American ship captain Robert Gray had discovered the mouth of the Columbia on the Pacific Coast. He had sailed up it and named it for his ship The Columbia. In 1805-06, expedition members were reinforcing America’s claim by keeping travel journals, branding trees, carving their names in rocks, and building Fort Clatsop—all signs of occupying the land, which was the second step in establishing a legal claim to ownership according to international law.

The “Doctrine of Discovery” meant land could be claimed in a “new country” by discovering the mouth of a river, which then entitled the discovering nation to all the land drained by that river. The “Graveyard of the Pacific,” the treacherous area at the mouth of the Columbia, had prevented its discovery by British and Russian sailing ships. The Columbia, the largest river in the Pacific Northwest, was the gateway to the lucrative Chinese overseas market for furs and a global trading network for the United States.

Four nations all had vested interests in the Pacific Northwest. The Spanish colonial empire stretched southward from the San Francisco Bay area to the tip of South America. The Russians, who were making enormous profits in the seal and otter skin trade, established a colony in the San Francisco Bay area in 1812. Great Britain, of course, had a colonial empire in Canada, and was challenging the United States for control of the border area from the Great Lakes to Oregon Country. The 49th parallel boundary line, which was settled by a treaty in 1846, finally ended their dispute over the Pacific Northwest.

JEFFERSON’S GOAL OF AN AMERICAN TRANS CONTINENTAL EMPIRE depended upon two things—re-inforcing America’s legal claim to the Pacific Northwest, and gaining control of the fur trade of the Northern Great Plains. The British had a strong presence in the region. British traders were active in the Pacific Northwest, and they controlled the fur trade through their allies the Blackfeet Indians. If America was going to stretch from “sea to shining sea,” the U. States had take control from Britain for the land and commerce on both sides of the Rocky Mountains.

It was up to Meriwether Lewis to inform the Black-feet that their days of unquestioned dominance over the buffalo plains and beaver streams east of the Rockies were over. Americans were going to supply their enemies with guns and ammunition, and Americans were going to trade for furs with any and all Indian tribes. Most decisively, the Americans planned to build a trading post in the heart of Blackfeet territory at the junction of the Marias and Missouri Rivers.

After crossing the Rocky Mountains, Lewis and Clark had split up to explore the tributaries of the Missouri River. It was the single most dangerous move of the entire expedition. Clark took one group to explore the Yellowstone River, which was the second largest tributary of the Missouri, and Lewis and three companions headed north to explore the Marias River. Lewis wanted to see if he could push the boundary line claim of the United States further north by following the river to its headwaters. At “Camp Disappointment” near Browning, Montana he realized that the headwaters of the Marias lay south of the 49th parallel.

The Marias was in the heart of Blackfeet Indian territory. British Canadian traders on the Saskatchewan River in Canada had been supplying the three Blackfeet tribes with arms and ammunition since the 1750’s. The other tribes of the region—the Shoshone, Flathead and Nez Perce—had only a handful of guns. When they hunted buffalo on the plains of Montana east of the Rocky Mountains, they traveled in groups for protection against the Blackfeet.

For thousands of years the Blackfeet had controlled the Northern Great Plains; the Shoshone and Flatheads had lived in the mountain valleys of western Montana; and the Nez Perce had lived west of the mountains in Idaho. The plains were filled with tens of millions of buffalo during their annual migration, covering the landscape as far as the eye could see. When Lewis and Clark met with these rival tribal leaders they promised the American government would supply them with arms and ammunition so that they could safely hunt for food and defend themselves against the Blackfeet.

CAPTAIN LEWIS MET THE BLACKFEET near the Two Medicine River, a tributary of the Marias on July 26th. A party of eight young Piegan, or Blackfeet, Indians had been out on a horse stealing raid. Over the evening campfire he informed them that an American trading post would be established at the junction of the Marias and Missouri Rivers. He wrote that he told them:

“I had been to the great waters where the sun sets and had seen a great many nations all of whom I had invited to come and trade with me on this side of the mountains.”

[also] “… that I had come in surch of them in order to prevail upon them to be at peace with their neighbors particularly those on the West side of the mountains and to engage them to come and trade with me when the establishment is made at the entrance of this river.”

The next morning, when the young men attempted to steal the Americans’ guns and horses, two of them were killed. Lewis, who had given a peace medal to one of them the night before, wrote that he:

“left the medal about the neck of the dead man that they might be informed who we were.”

To escape pursuit by the Blackfeet, the four men rode as fast as they could for the Missouri River. They rode through immense herds of buffalo for hours, continuing on into the night under stormy moonlit skies. Lewis praised the quality of his Indian horse and estimated they covered 100 miles before they ended their ride at 2 A. M. They awoke at daybreak, and Lewis and the others were so sore they could scarcely stand. But he warned them that:

“our own lives as well as those of our friends and fellow travelers depended upon our exertions of this moment.”

They thought they heard gunfire when they arrived at the Missouri, and after traveling along the river’s edge for some miles, they had “the unspeakable satisfaction” to find other members of the expedition bringing down the white pirogue and five smaller canoes. Reunited, they proceeded on to their rendezvous site with Clark and the others at the junction of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers.

THE SHOTS THAT Meriwether Lewis and Reuben Fields fired, killing the two Blackfeet, were the beginning of more than a quarter of a century of warfare between the Black-feet and American fur trappers. At least two members of the Lewis and Clark expedition, who returned to trap beaver in Montana, lost their lives to the Blackfeet: John Potts in 1808 and George Drouillard in 1810. John Colter, Potts companion, only escaped death by making his famous run for his life.

Over twenty American trappers were killed by the Black-feet in 1808 alone. The Blackfeet not only wanted to kill them, they were after their beaver pelts, which often represented sizable fortunes, and were traded for ammunition and alcohol with the British traders on the Saskatchewan. The artist Alfred Jacob Miller who traveled in the Far West in 1837 said that the Blackfeet still attacked 40-50 trappers per season.

“They are the sworn enemies of all—Indians and white men alike…Undoubtedly the Blackfeet have the worst reputation for war and aggression of all the Indians of the North-West. Their very name is a terror to most of the Indian tribes.”

When Meriwether Lewis ventured into Blackfeet territory he was directly challenging British control of the Northern Plains through their Blackfeet proxies—just as establishing Fort Clatsop on the Pacific Coast challenged the British claim to the Oregon Country. Within a few years, the United States and Great Britain would be at war with each other. The arming of Indians by the British and the encouraging of attacks on Americans was a direct cause of the War of 1812.

MERIWETHER LEWIS WAS SHOT himself while out elk hunting with Pierre Cruzatte on August 11th, 1806. He wrote in his journal:

“I instantly supposed that Cruzatte had shot me in mistake for an Elk as I was dressed in brown leather and he cannot see very well; under this impression I called out to him, damn you you have shot me”

Lewis spent an uncomfortable month recovering from his wounds, as the rifle ball had passed through both his left thigh and right posterior. He was lucky in that it didn’t penetrate the sciatic nerve of his left leg, which would have crippled him for life. The next day Lewis wrote:

“my wounds felt very stiff and soar this morning but gave me no considerable pain. there was much less inflammation that I had reason to apprehend there would be. I had last evening applied a poltice of peruvian barks.”

Two hunters from Illinois were encountered the next day on August 12th; they were the first white men they had seen since leaving the Mandan-Hidatsa Villages in the spring of 1805. Joseph Dixon and Forest Hancock, who had left the Illinois Country in the summer of 1804, were on their way to Montana to trap beaver. Lewis gave them advice as to the best beaver stream locations, and a “file and a couple of pounds of powder with some lead” before hurrying on to meet up with Clark at the the junction of the Yellowstone and Missouri, their designated rendezvous.

Lewis then wrote his last words on the journey:

“at 1 P. M. I overtook Catp. Clark and party and had the pleasure of finding them all well. as wrighting in my present situation is extremely painfull to me I shall desist until I recover and leave to my Capt. C. the continuation of our journal.”

Clark’s journal notes reveal that Dixon and Hancock turned around and returned to the Mandan Villages for a longer visit with them. Private John Colter, an expert hunter, received special permission to leave the expedition and went back west with the two hunters.

The seven Mandan-Hidatsa Villages on the Knife River in today’s North Dakota were a prosperous center of trade, with several British traders living there, and a population of about 3,000. It was the home of Sacagawea and her husband Toussaint Charbonneau. After leaving the villages, William Clark realized that he missed their little son, Pompey, tremendously, and he wrote a letter a few days later asking the Charbonneaus to allow him to raise and educate him. He called Pompey “my little danceing boy” and asked them to bring their son, who was then 18 months old, to St. Louis, and requested they stay with him there until he was old enough to leave his mother.

THE MANDAN CHIEF SHEHEKE accompanied the expedition for the rest of their journey. His entourage consisted of his wife and son; and a French-Canadian interpreter, Rene Jessaume, with his Mandan wife and two children. The Mandan Chief had been invited to visit President Jefferson in Washington. The families traveled in two dugout canoes, lashed together with poles, for speed and stability. The Captains called Sheheke, “Big White Chief.” He was six feet, ten inches tall and fair skinned. Sheheke means “White Coyote” in the Mandan language. (His portrait appears on page 272.)

The Mandan Indians were a subject of great curiosity around the world—they were thought to be “White Indians,” descended from the Welsh Prince Madoc and his followers who—according to legend—had come to Mobile Bay on the Gulf Coast in 1170 A. D. and gradually migrated north along the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. In the time of Lewis and Clark this was a very popular subject.

Lewis and Clark carried a copy of a map made by John Evans, a Welshman who had traveled to the Mandan Villages in 1796 to see if the Mandans were, indeed, descended from the Welsh. Evans concluded they were not, but his objectivity was questionable because he received money from, and lived as a guest of, the Spanish governor in New Orleans after he returned from his travels. He had originally been sent to investigate the matter by a Welsh nationalist group in England.

“Welsh Indians” had been a hot topic since the time of Queen Elizabeth I. The Queen and her advisors promoted the idea of Welsh Indians in order to make a claim under the Doctrine of Discovery for legal possession of the New World by the English rather than the Spanish. Regardless of whether they were—or were not—of Welsh descent, President Jefferson would have been eager to meet the Mandans. Both he and Meriwether Lewis were of Welsh descent.

William Clark grew up in Louisville hearing about the Welsh Indians. It was a local tradition that the White Indians had lost a major battle with the Red Indians at the Falls of the Ohio, where thousands of human bones had been found on an old battlefield. His brother George Rogers Clark was the leading expert in the west on prehistoric Indians and other studies in the natural sciences. Today, the Falls of the Ohio Interpretive Center has an exhibit displaying ancient armor and coins found in the area of the Falls.

The artist George Catlin visited the Mandan Villages in 1832. In North American Indians Letter # 13 he wrote extensively about them and stated:

“Governor Clarke told me before I started for this place that I would find the Mandans a strange people and half white.”

The French explorer Verendrye and others also commented on their white appearance. Perhaps DNA testing will reveal some answers. It is interesting that Lewis and Clark kept their opinions to themselves about White Indians—other than referring to Sheheke as “Big White Chief.”

THEY FINALLY HEARD NEWS FROM HOME on September 2nd, when they encountered the trader James Aird coming up river. He told them of the “maney Changes & misfortunes” that had occurred since they left the Illinois Country in the spring of 1804. Their friend Pierre Chouteau had lost his house in a fire, and there were a couple of international incidents involving American ships and sailors, but the news that would have the most impact on their lives was this:

“General Wilkinson was the governor of the Louisiana and at St. Louis 300 of the american Troops had been Contuned on the Missouri a few miles above its mouth. Some disturbance with the Spaniards in the Nackatosh Country is the Cause of Their being Called down to that Country… and that Mr. Burr and Genl. Hambleton fought a Duel, the latter was killed &c. &c.”

The news must have been too much to be absorbed. What Meriwether Lewis didn’t realize was that for the rest of his all too short life—for the next three years—he would be dealing with these matters. He was 32 years old, and within a few months President Jefferson would appoint him to the post of Governor of Louisiana Territory, replacing General Wilkinson who still remained in command of the United States Army.

It seemed from the news they received that war with Spain might have started on the borderland area of the Sabine River between New Spain (Texas) and the Arroyo Hondo near Natchitiches, Louisiana. (“Nack-a-tosh” is how locals still prounce the name.) But the news wasn’t all bad—James Aird generously gave every man on the expeditionn who smoked enough tobacco to last until they reached St. Louis. He also gave them a barrel of flour which they hadn’t tasted in many months, and they gave him six barrels of corn to take up river.

They were near the Big Sioux River and the gravesite of Sergeant Charles Floyd, the only man to die on the expedition. They paid a visit to his grave on the top of the high hill where they had buried him, and found that his grave had been opened. They refilled the grave, and continued on.

THEY WERE ALMOST CAPTURED BY THE SPANISH as they neared the mouth of the Platte River. The Spanish government in New Spain had sent out three previous expeditions to capture “Captain Merry Weather,” as they called him—all ending in failure. But their last attempt almost succeeded, as Spanish troops were only 4-5 days march away when the Lewis and Expedition passed the Platte on September 10th.

General Wilkinson had written to the Spanish in March, 1804 proposing that they arrest Lewis and Clark. It was shortly after he presided over official ceremonies taking possession of the Louisiana Purchase for the United States at New Orleans on December 20, 1803. The General—who had been in the pay of Spain since 1787—received $12,000 for a secret report entitled “Reflections on Louisiana’” informing them of the expedition’s goal to reach the Pacific Ocean.

The Pawnee Indians stopped the fourth and last attempt by the Spanish to capture “Captain Merry” in late August or early September. When a Spanish military force of about 360 men, headed by Lieutenant Facundo Melgares, arrived at their village on the Republican River near today’s Kansas-Nebraska border, they refused to allow him and his troops to continue on with their march to the Missouri River. Yet a few weeks later, when Zebulon Pike arrived with an expedition of about 25 men, they allowed them to continue on their journey west towards Sante Fe. Pike and his men spent almost two weeks at the village, from September 25-October 7th, and learned from French traders who arrived there on October 4th that the Lewis and Clark Expedition was on its way home.

LEWIS AND CLARK WERE MAKING FAST TIME, traveling 78 miles in one day, as they reached the mouth of the Platte River. Clark wrote that everyone was “extremely anxious” to get home to their friends and Country. And he was pleased to report that his “worthy friend can walk and even run nearly as well as ever he Could.” The next day, September 10th, they met another trader on the river, who gave them a bottle of whiskey, and told them the news that General Wilkinson and his troops had descended the Mississippi; and that an expedition had set out for the southwest on the Arkansas River under the leadership of Captain Zebulon Pike and Wilkinson’s son, Lieutenant James B. Wilkinson.

Now they were meeting trading parties going up river almost every day and continuing to receive gifts of whiskey. Near Leavenworth, Kansas, Clark wrote “Sung Songs until 11 oClock at night in the greatest harmoney.” Though they were finding it hard going on the Missouri—between the humidity and warm weather they were no longer accustomed to, the mosquitoes, and the sandbars and snags—they were very excited and happy to be arriving home.

CAPTAIN JOHN McCLELLAN was encountered near the Grand River on September 17th. (A few days earlier Lewis and Clark had met an old friend from army days, the trader Robert McClellan.) They stayed up talking “until near mid night.” McClellan said they had long ago been given up for dead and were almost forgotten; but that the President had not yet given up hope for their safe return.

He told them that he had recently resigned from the army and was on a “speculative venture” to New Spain. McClellan was, in fact, a business partner of General Wilkinson, and they were going into trade together. He described his intentions as—first, the building of a trading post at the mouth of the Platte; then, the making of friends with the Pawnee and Otoe Indians; and finally using their influence to set up a successful trade with Sante Fe to obtain the “Silver & gold of which those people abound.”

For reasons unknown, none of this happened. His real destination may always have been the fur country of the Northwest. Historians believe that McClellan’s party went on to become the mysterious group of Americans known to history as the “James Roseman, Zachary Perch/Jeremy Pinch” party who were present in Montana in 1807-1810. It is probably no coincidence that “Zachary Perch” appears to be a word play on the name “Zebulon Pike.” None of these names are found in military records, so the signature of Zachary Perch could also have been misread as Jeremy Pinch.

In any event, these names were the aliases of Americans who sent letters to the British trader David Thompson warning him that the region was under American control. Thompson was establishing a trading house for the Northwest Company near Banff, Canada in 1807, when he received two threatening letters, delivered by Indian messengers, dated “Fort Lewis, Yellow River, Columbia, July 10, 1807” and “Poltitopalton Lake, September 29, 1807.” The men were apparently somewhere in the vicinity of Missoula, Montana in the Bitterroot Mountain Valley. The letters charged Thompson with not acknowledging “the authority of Congress over these Countries.” The first letter contained regulations governing commerce with the Indians under American rules, written in language very similiar to the language in documents Zebulon Pike was carrying on his expedition to the Southwest. Thompson responded to the second letter saying he had no authority to discuss these matters.

Copies of the letters were found by Hudson Bay Company historians in 1938. It is thought that all the men associated with the mystery group—42 men or more—were killed by Blackfeet Indians in the next few years. Dr. Gary Moulton, the editor of the Lewis and Clark Journals, says that three members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who returned to Montana, are believed to have joined the McClellan party and were later killed. They are Pierre Cruzatte, Joseph Field(s) and John B. Thompson.

THEY WERE CONTENT TO EAT PAWPAWS, a native tree fruit, tasting somewhat like bananas, as the sped home. They still had a few biscuits, and didn’t want to waste any time hunting. Clark wrote that when they saw some cows on the bank everyone cheered. That night, on September 20th, they reached the little French village of La Charette, and fired off their guns in a salute—a salute which was returned by the five trading boats docked at the village. The next day they arrived in St. Charles, where they enjoyed a day of feasting and hospitality. On September 22, they visited Fort Belle Fontaine for the first time; the military cantonment on the banks of the Missouri had been established the previous year during their absence. The next morning they took the Chief to the commissary store at the fort and outfitted him with some new clothes.

THEY RECEIVED A “HARTY WELCOM” and were met by “all the village” of St Louis when they arrived at noon on September 23rd. A letter to a newspaper described them as looking like “Robinson Crusoes.” Lewis and Clark were hosted by Pierre Chouteau and his family, and after a short round of visits, they sat down to write letters to be sent off with the waiting post rider. Lewis wrote to the President, and Clark wrote to his brother Jonathan in Louisville, announcing their safe arrival back in St. Louis.

They had survived the perils of the wilderness—would they be able to survive the political perils of the new republic?

CONSPIRACIES ARE NOT EASILY UNDERSTOOD, and—by their very nature—they are not meant to be. The last three years of Meriwether Lewis’s life were often involved with the conspiracies of Aaron Burr and James Wilkinson, and so in this chapter, they will be discussed. Lewis must have known the two conspirators rather well. When Burr was the Vice President of the United States, Lewis was President Jefferson’s private secretary; and Lewis served as a career army officer on the frontier under General James Wilkinson.

Burr and Wilkinson were always interested in the Spanish territories bordering the United States as a source of riches and power. Their conspiracies may have played a role in two of the great dramas of the early republic—the closely contested presidential election of 1800, and Burr’s duel with Hamilton in 1804. It seems likely they were planning to invade Mexico in 1801 if Burr had won the presidency. In 1804, Burr may have killed Hamilton to prevent his rival from competing with him to lead a new invasion scheme with General Wilkinson—the one that became known as the “Burr Conspiracy” or the “Burr-Wilkinson Conspiracy.”

THE BURR-WILKINSON CONSPIRACY dominated the news in 1807—far eclipsing news of the return of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The conspiracy was reaching its final stages as Lewis and Clark were returning home in September of 1806. Burr and Wilkinson were planning to invade Spanish territories in the event of war with Spain and to take possession of the Spanish lands of West and East Florida, Texas, and Mexico. A new, independent empired would be formed with Burr as its ruler.

Several versions of the invasion plot were in circulation. It was said that the western states would break away and join the new empire—or that Burr’s purpose was to establish a new agricultural community on lands near Monroe, Louisiana—or that the British and American navies would lend their support—or that the city of New Orleans would be seized and money plundered from its banks to finance an invasion of Vera Cruz—or that the United States Army would be participating. The country was in a state of high alarm, and many people were anticipating a war with Spain and an invasion of Spanish territories.

GENERAL ANDREW JACKSON hosted a public dinner for Aaron Burr on September 26, 1806 in Nashville. Burr told the guests that Spanish soldiers had invaded American soil east of the Sabine River, and that a war with Spain was imminent. Jackson issued a proclamation for the Tennessee Militia to be ready for duty, and wrote to President Jefferson that Tennessee would be supplying three regiments.

Meanwhile, Burr’s fellow conspirator, General Wilkinson was in the process of stopping the impending war with Spain over the Sabine River boundary issues. On September 27th, Spanish commander Lieutenant Colonel Simon de Herrara evacuated his troops from east of the Sabine River, and retreated to the west bank, effectively removing all cause for war. Shortly after this, a messenger arrived from Aaron Burr, bringing a letter in cipher code for Wilkinson detailing plans for the invasion. The General took no action until October 20th when he wrote to President Jefferson disclosing a plot to invade Vera Cruz by a powerful group of unnamed individuals, who would reach New Orleans in December. The General had decided to betray Aaron Burr, and that his own future was better served as an informer. On November 7th, he signed a “Neutral Ground Agreement” with Herrara establishing a neutral border zone area.

HUNDREDS OF VOLUNTEERS were traveling in small groups to join the expedition. They were to rendezvous at the Red River south of Natchez, Mississippi. Boats were being built up and down the Ohio River. Altogether, there were probably 1,500-2,000 men on the move, planning to join the expedition. Many believed the expedition was secretly supported by the administration. They were being told their final destination was Mexico, but that they would first rendezvous at the Bastrop lands between the Red and Oauchita Rivers.

The Neutral Ground Agreement was signed between General James Wilkinson and Lieutenant Colonel Simon de Herrara on November 5, 1806. It established the “Sabine Free State” or a “Neutral Strip”—an area that was off limits to the soldiers of both countries, and was not open to settlement. The agreement was not ratified by either government, but endured until the Adams-Onis Treaty established the Sabine River as the boundary line between the two countries in 1821.

The western boundary was the Sabine River and the eastern boundary was the Arroyo Hondo (“Deep River”)—today’s Calcasieu River. The southern boundary was the Gulf of Mexico. The area was about 55 miles at its widest and about 110 miles in length. It was an area of wetlands and bayous in the south and pine forests in the north.

The Neutral Strip became a haven for outlaws, fugitive slaves, mixed race people, and filibuster expeditions. The local inhabitants were the few remaining Attakapas Indians. The Lafitte Brothers kept African slave camps for the slave trade here. Their pirate headquarters were on nearby Galveston Island.

In early December of 1806, a group of men were assembling on Blennerhassett Island, the home of a wealthy Irish aristocrat, in the middle of the Ohio River near Parkersburg, West Virginia. Fifteen gun boats for the expedition, “ample enough for 500 men,” were being built at nearby Marietta, Ohio. However, a messenger from Jefferson informed the Ohio governor of Burr’s plans, and on December 9th, local militia seized the boats and a keelboat for provisions. Harmon Blennerhassett and the other conspirators hurriedly left the island the next day.

The events on the island would later form the basis of the federal case against Aaron Burr and his trial for treason in Richmond, Virginia. Burr was not present on the island because he had been undergoing two grand jury investigations in Kentucky. The grand juries were attempting to investigate charges that Burr was planning an invasion of Mexico, but due to lack of witnesses who were willing to testify, he was not indicted.

JEFFERSON ISSUED A PROCLAMATION on November 27th, finally responding to the crisis and warning the country that:

“sundry persons—are conspiring and confederating together to begin—a military expedition or enterprise against the dominions of Spain.”

The President instructed all participants in the expedition to withdraw from the enterprise without delay. Jefferson had been waiting for as long as possible to respond to the conspiracy—he wanted Burr to commit an overt act, so that a charge of treason could be proved against him. The October 20th message from General Wilkinson warning him of the conspiracy forced his hand. So he ended up charging an unnamed group of individuals with preparing a filibustering expedition—a lesser offense, but still unlawful. (A filibuster is a unauthorized military expedition into a foreign country to support or start a revolution.)

Blennerhassett and about 30 companions were joined by recruits from the Louisville area as they traveled down river to meet Burr and his Tennessee recruits at the mouth of the Cumberland River. The flotilla consisted often boats with a total crew of about 60 men. They were carrying agricultural implements and concealed weapons. Three boats with ammunition had been stopped at Louisville by the authorities.

When the boats reached Fort Massac on the Ohio River, Burr told the fort commander, Daniel Bissell, that he now knew that General Wilkinson had made an agreement with the Spanish commander establishing the “Neutral Ground” area. He had just come from his second visit to Nashville, where his reception from Andrew Jackson had been much cooler.

BURR STILL THOUGH THE CONSPIRACY to seize New Orleans was in place. The plot was that the Mexican Association of New Orleans would turn over the city to Burr in a coup d’etat. Burr’s stepson, John B. Prevost, was Judge of the Superior Court of New Orleans Territory. Prevost, and other wealthy and influential men were leaders of a 300 member association whose purpose was to foster a war for Mexican independence. Many American residents in New Orleans were eager to see a revolution begin. On September 23, 1806, the New Orleans Gazette, the only English language newspaper, urged:

“Gallant Louisianians! Now is the time to distinguish yourselves… Should the generous efforts of our Government to establish a free, independent republican empire in Mexico be successful, how fortunate, how enviable would be the situation in New Orleans! The deposit at at once of the countless treasures of the South, and the inexhaustible fertility of the Western States, we would soon rival and outshine the most opulent cities of the world.”

Historian Thomas Abernethy, author of The Burr Conspiracy, says that Burr believed that Wilkinson had arranged for a truce on the Sabine because of orders from the President; but that Burr still expected Wilkinson to arrange for the city’s secession.

Burr stopped at Fort Pickering on the Chickasaw Bluffs (now Memphis, Tennessee), where three years later Meriwether Lewis would spend some of the last days of his life. Burr spent a day persuading the only officer at the fort, Lieutenant Jacob Jackson, to resign his commission and return home to Virginia to raise a company to join his expedition. Burr was trying to fill the manpower loss caused by the evacuation of Blennerhassett Island before all the recruits arrived.

On January 10th, Burr in an advance boat with 12 men, arrived at Bayou Pierre north of Natchez (near Port Gibson, Mississippi). His friend showed him a newspaper featuring the cipher code letter to Wilkinson. He learned that Wilkinson had betrayed him; of the President’s proclamation, and an order for his arrest issued by the Governor of Mississippi Territory. The next day he surrendered.

NEW ORLEANS WAS IN A PANIC. General Wilkinson had arrived in the city on November 27th, announcing that Burr was on his way to attack the city with 2,000 men. By the time of Burr’s arrest, the General had spent six weeks reinforcing New Orleans’ two forts and demanding that Governor William Claiborne and the Orleans Territorial Legislature give him special powers. Denied his request for martial law, he proceeded to do what he wanted to do anyway—he rounded up five fellow conspirators who had arrived in New Orleans, imprisoned them, and shipped them out of the area to Richmond, Virginia—where they were released due to lack of evidence. The General was in an awkward position. He was trying to prevent what he knew was a real possibility—that Burr’s volunteers would be arriving to seize New Orleans—although members of the Mexican Association were denying the existence of any such plan. If Burr had seized control of New Orleans, it was anticipated that an armyt of 7-10,000 men would assemble there to invade Mexico in the spring.

WHAT WERE THE MOTIVES of Burr, Wilkinson and Jefferson in the conspiracy? Why did the President place General Wilkinson and Burr’s family members in positions of power in the new territories? Why did Wilkinson betray Burr? Why didn’t the war with Spain happen?

Thomas Jefferson must have been anticipating a war with Spain in March, 1805 when he appointed Wilkinson the first Governor of Louisiana Territory; Burr’s brother-in-law, Joseph Browne, the first Territorial Secretary of Louisiana; and Burr’s stepson, John B. Prevost, the highest ranking Judge in Orleans Territory. Before his appointment Wilkinson had delivered a set of maps of Texas and Mexico to the War Department. Wilkinson continued as Commanding General of the U. S. Army while serving as Governor of Louisiana, reflecting Jefferson’s concern for the security of the borderlands area.

During 1804-06, after leaving the Vice-Presidency, Burr had been deep in negotiations with British agents, French exiles, and the Spanish minister, plotting the invasion of Mexico. The British negotiations had come to nothing due to the fall from power of Lord Melville and the death of Sir William Pitt in January, 1806.

In the summer of 1806, Burr was meeting with General Jean Victor Moreau, one of Napoleon’s top generals living in American exile; and the Spanish minister to America, the Marquis de Casa Yrujo. Burr’s chief of staff for his invasion plans was a French refugee, Colonel Julien De Pestre, who had served in both the French and British armies. De Pestre accompanied Burr on his travels, and stayed loyal to him through his trial for treason, refusing to testify against him.

James Madison, who was serving as Jefferson’s Secretary of State, suggested that Yrujo was allied with the French party of Spain, and that this was behind Burr’s conspiracy. This is the most likely story—that the final conspiracy plan involved working with French agents to liberate Mexico from Spanish rule. Did Jefferson know that Burr was conspiring with foreign governments? Senator William Plummer (Federalist-New Hampshire) wrote in his journal on January 17, 1807 that he had dined with Jefferson and the President had told him:

“… he did not believe either France, Great Britain, or Spain was connected with Burr in this project, but he tho’t the marquiss de Yrujo was—that he had advanced large sums of money to Mr. Burr—and his associates. But he believed Yrujo was duped by Burr. That last winter [1805-06] there was scarse a single night, but that at a very late hour, those two men met & held private conversations. I have since ascertained the fact.”

WILKINSON WAS THE PIVOT POINT, and a war with Spain over the Sabine River boundary issue would be the decisive moment. Spanish troops crossed the river in March of 1806. They crossed the river to provoke a war with the United States. Who wanted the war?—Mexican revolutionaries, including army officers, working with French agents, who were relying on the promise of support from the filibustering expedition led by Aaron Burr. What did they hope to achieve? A new country, led by Aaron Burr, which would benefit the commercial interests of New Orleans and others.

General Wilkinson had taken his time responding to the border invasion. On May 16th, orders had been issued for him to proceed to the Sabine “with as little delay as possible,” but he didn’t head south with his troops until August. He reached Natchez, Mississippi, 25 miles east of the Sabine River, on September 7th.

Wilkinson spent the summer months organizing two expeditions—the mysterious one with his business partner John McClellan that wound up in the northwest; and the famous Zebulon Pike Expedition to the Southwest. His own son, James B. Wilkinson accompanied the Pike Expedition part of the way—leaving before Pike and his companions were captured by the Spanish. Before Wilkinson left St. Louis he wrote a friend that he did not anticipate a war with Spain over the Sabine River.

When the General finally arrived at the Sabine on October 22nd, he was not entirely certain, whether it would be war or peace. The day before he had sent Thomas A. Smith (the older brother of John Smith T.) off to Jefferson with a message hidden in his boot, which the General hoped would provide cover for himself. Historian Thomas Abernethy remarked about this message:

“… he said he was enclosing a paper which had fallen into his hands. The louder the Brigadier talked of his honor, the faster President Jefferson should have counted his spoons, for the document enclosed was obviously written by Wilkinson himself.”

In any event, General Wilkinson and Lieutenant Colonel Herrara—on their own authority—signed the “Neutral Ground Agreement” on November 5, 1806, thus avoiding war. Herrara was disobeying orders, but Wilkinson was anticipating the orders of Jefferson to avoid war.

Abernethy stated that Herrara had the courage to defy orders from his superiors, who would have been ruined if he had disclosed their complicity in the plot to revolutionize Mexico with French support. Herrara, who had an English wife, had visited the United States and met George Washington, whom he admired greatly. Abernethy also noted that William Simmons, the War Department accountant, reported that Wilkinson received $16,883.12 in October-November, 1806 and January, 1807 in unaccounted for funds.

LIEUTENTANT ZEBULON PIKE and his men were captured by Mexican troops that winter. After Pike’s capture, he became a guest under house arrest in Herrara’s home in San Antonio. Pike’s diary entry for June 13, 1807 noted a conversation between Herrara, who was also Governor of Nuevo Leon Province; Colonel Manuel Cordero, Governor of the Province of Texas, and himself. Herrara told them that after he made his report about the Neutral Ground Agreement that—

“Until an answer was received … I experienced the most unhappy period of my life, conscious that I had served my country faithfully, at the same time that I had violated every principle of military duty. At length the answer arrived, and what was it, but the thanks of the viceroy and the commandant-general for having pointedly disobeyed their orders, with assurances that they would represent his services in exalted terms to the king [of Spain].”

Pike and his men returned to the United States under military escort two weeks later, on July 1st.

TWO OTHER POSSIBLE CONSPIRACIES preceded the famous filbuster expedition of 1806, and both involve other famous episodes in American history—the Burr-Hamilton duel of 1804, and the famous close election in 1801 between Burr and Jefferson for the presidency of the United States.

In 1801, the election of the third president of the United States hung in balance that winter. Due to a tie vote in the electoral college between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, the House of Representatives became responsibile for choosing who would become president. The second highest vote getter would become the Vice-President under laws existing at that time. It took a week of balloting, and finally on the 36th ballot, Jefferson was declared the winner on February 17, 1801.

IF BURR HAD WON THE ELECTION OF 1800 would an invasion of Spanish territories taken place? It is quite possible, and would have involved the troops stationed at Cantonment Wilkinsonville near Cairo, Illinois and the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. On January 5, 1801 about 700 soldiers arrived at Wilkinsonville. Approximately 1,000-1,500 men were stationed there during its peak occupancy between March and August, 1801.

Six or seven of these soldiers later joined the Lewis and Clark Expedition: Sergeant Patrick Gass; Privates Thomas Proctor Howard, Hugh McNeal, John B. Thompson, Joseph Whitehouse, Richard Windsor, and perhaps Silas Goodrich. A cantonment is a military camp without fortifed walls. In recent years the site has been the subject of archeological digs and research conducted by Southern Illinois University.

The contractor at the cantonment, John R. Williams—who later became the first Mayor of Detroit—wrote about the possibility of the cantonment being used as a staging ground for an invasion of Spanish territory in an 1845 letter:

“Mr. Jefferson having been elected President of the U. S. The policy of the Government changed instead wresting the posts on the west bank of the Mississippi by force of Arms as was previously contemplated—They were eventually obtained by peaceable & Successful negociation.”

In March, 1802 the U. S. Army numbered about 3,500 soldiers, so the troops stationed at Cantonment Wilkinsonville represented between 28-42% of the total strength of the army. The troops served a definite military purpose during a very unstable time in the Mississippi Valley, regardless of any plans to invade Texas. Napoleon was intending to take back the Mississippi Valley and Louisiana in 1801-02, but over 50,000 French soldiers died of yellow fever while they were fighting the slave rebellion in San Domingo. It was their deaths which persuaded Napoleon to sell Louisiana to the United States in 1803; in 1804 San Domingo gained its independence and became known as Haiti.

THE PHILIP NOLAN EXPEDITION TO TEXAS was most likely a filibuster unit tied to invasion plans from Cantonment Wilkinsonville. Nolan was a young Irishman who had lived in Wilkinson’s household as a teenager. He made several long trips into Texas, to catch wild horses, and was famous for his strength and daring. He also made maps during these trips—and it was his maps that Wilkinson delivered to the War Department in the winter of 1804-05.

In December, 1801, Nolan led a filibuster of 25 men into Texas where they built a stronghold of small forts and mustang corrals in the Hill Country of Texas (near Blum, Texas south of Dallas). On March 21st, 1801 Nolan was killed by Spanish soldiers. It was two weeks after the inauguration of President Jefferson. Nolan was the only man killed, though others were jailed and some escaped. One of the men who escaped, Robert Ashley, later helped Aaron Burr’s in his attempt to escape capture by Wilkinson’s men in 1807.

ONE MORE INDICATION of an early Burr-Wilkinson Conspiracy is a statement by J. H. Daviess, the District Attorney in Kentucky who instigated the grand jury investigations of Aaron Burr in 1806. He was a staunch Federalist, who attempted several times to warn President Jefferson of the Burr-Wilkinson Conspiracy. In gathering evidence to confirm his suspicions he met with General Wilkinson. Daviess wrote in his book, A View of the President’s Conduct Concerning the Conspiracy of 1806, published in 1807, that the General was showing him some maps of New Mexico when—

“… after some conversation about it, tapping it with his finger, told me in a very low and very significant tone and manner, that ‘had Burr been president, we would have had all this country before now.’”

THE BURR-HAMILTON DUEL may have been connected to the same type of conspiracy plans. Historian Thomas Fleming in his book, Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and the Future of America, provided some convincing evidence that General Wilkinson was considering both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr as potential partners for him in a new invasion plan for Mexico. The two men were bitter enemies, and Fleming speculates that Burr killed Hamilton to prevent his taking his place with Wilkinson in the scheme which became known as the Burr-Wilkinson Conspiracy of 1806.

The duel occurred on July 11, 1804 while Burr was still serving as the Vice President of the United States. Hamilton had been Secretary of the Treasury under George Washington, and had served as de facto commander of the army under Washington in 1798-01 during the Quasi-War with France. Hamilton and Wilkinson had made the plans for Cantonment Wilkinsonville together.

Less than two months before the Burr-Hamilton duel on May 23, 1804 General Wilkinson had sent Aaron Burr a very confidential note:

“To save time of which I need much and have little, I propose to take a bed with you this night, if it may be done without observation or attention—Answer me and if in the affirmative I will be with [you] at 30 after the 8th hour.”

The subject of their meeting may have been the same as that which Wilkinson had written about in a letter to Alexander Hamilton on March 26th. Wilkinson invited Hamilton to come to New Orleans, adding that:

“I would give a Spanish Province for an Interview with you. My topographical of the S. West is now compleat. The infernal designs of France are obvious to me, & the destinies of Spain are in the Hands of the U. S.”

During the Quasi War with France, which was an undeclared war fought entirely at sea in 1798-01, Hamilton had been eager to make a pre-emptive strike against the Spanish territories of the two Floridas and Texas, in the event of an expanded war with France. When John Adams negotiated a peace truce with France in September, 1800, it ended their plans.

THERE WERE MANY SUCH PLANS during these years of the early republic. The first presidents skillfully negotiated the survival of the American Republic in a time of the Napoleonic world wars between the European powers. France and Great Britain wanted to regain their former control of the Missisippi Valley, and Spain wanted to hold onto its power as long as possible.

There were many attempts to fragment the United States, and establish separate governments. But of all the early plotters, Aaron Burr and James Wilkinson posed the greatest threats. Aaron Burr—because he was connected on a high level with leaders around the world and was capable of starting a new government—was probably the greater threat.

The Spanish Empire was in the process of breaking up, and its colonies in the New World were seen as prizes to be taken. Great Britain and France were both interested in fostering revolutions in the colonies. If Jefferson didn’t keep Burr and Wilkinson busy, others might. And, as always, changing politics and fortunes of war shifted everyone’s plans.

Neither Burr nor Wilkinson was ever viewed as “trustworthy” by government leaders. But they both had an uncanny ability to land on their feet despite whatever threatened their survival. Jefferson had decided to remove Wilkinson from his command of the U. S. Army, and had already removed him from his post as Governor of Louisiana Territory in the last months of 1806, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition was returning home. The General had been alerted by a Senator friend that he would lose his military appointment in the next session of Congress. It was undoubtedly a deciding factor in his decision to betray Aaron Burr.

Jefferson believed that the Spanish territories would fall into the hands of the United States without war. He was determined to stop Burr’s plans to establish a rival empire in the southwest. He believed that the two Floridas and Texas could be acquired by negotiation and purchase rather than war.

WHEN BURR SURRENDERED at Bayou Pierre on January 11, 1807 he chose to surrender in Mississippi Territory rather than Orleans Territory where Wilkinson held power. Wilkinson wanted to try Burr in a military court. Instead, Burr’s trial was conducted in a civil court at the small territorial capitol of Washington, Mississippi a few miles north of Natchez. He and his men were entertained at dinners and balls by the local residents, and many of his followers settled in the area.

On February 4th, a grand jury packed with Federalists absolved him of all charges. Local residents were satisfied that Burr’s only aim was to invade Spanish territories, not to cause a break up of the western states. But after the trial was over, Burr was still held on bond, despite the fact he wasn’t indicted.

Wilkinson sent six men armed with pistols and dirks to seize him. They had no warrants or criminal charges in their orders. Burr, fearing for his life, forfeited his $5,000 bond and disappeared into hiding the day after his hearing. A $2,000 reward was offered for his capture. The Governor of Mississippi Territory announced he was a fugitive from justice, and the former Vice President of the United States was now on the run.

Burr was captured on February 18th in the company of Robert Ashley, near Mobile, Alabama. They were on their way to Pensacola, Florida. Spanish officials from Pensacola had visited Burr while he was in jail in Washington, Mississippi. Burr was put under arrest at Fort Stoddert (30 miles north of Mobile) and Major Ashley once again escaped from capture. An attack on Mobile and Pensacola, supported by local revolutionaries was undoubtedly being planned, until the commander of the fort decided to send his famous prisoner on his way.

On March 5, 1807, Aaron Burr was taken from Fort Stoddert under military escort to Richmond, Virginia where he would stand trial for treason.

UPON THEIR RETURN TO ST LOUIS Lewis’s role as the true commander of the expedition now became apparent—he was responsible for the financial reports; discharging and paying the expedition members; delivering the artifacts they had collected to the President; bringing the Mandan Chief and his entourage to Washington; and publishing the account of their journey. William Clark, on the other hand, was anticipating spending time with his family in Louisville, and going to Fincastle, Virginia to woo his young sweetheart Julia Hancock.

Immediately after reaching St. Louis, on September 23, 1806, Lewis sent off a lengthy and detailed report to Jefferson describing the geography and fur trade potential of the country they had explored. He provided a copy of the report for Clark to send to his brother Jonathan in Louisville. It was expected the report would be published in the newspapers, and that Clark’s letter would become the first notice of the safe return of the expedition and what they had found.

For the next month they stayed in St. Louis awaiting the arrival of Pierre Chouteau and a delegation of Osage Chiefs who were going to travel east with them; attending to paperwork; and enjoying the hospitality of their friends. They also heard a lot of disturbing news about government affairs in St. Louis.

The wealthy French residents of St. Louis had petitioned President Jefferson to appoint Aaron Burr’s brother-in-law, Joseph Browne, the new Governor of Louisiana Territory. Browne, the Territorial Secretary, became the Acting Governor after Wilkinson left on his long-delayed departure for the Sabine River on August 16th. The petition, submitted by Auguste Chouteau on July 15th, praised General Wilkinson in the most extravagant language, the petitioners stating that:

“their warm approbation, their unshaken confidence, and their firm attachment have been often expressed [regarding Wilkinson]… the virtues of his heart, equalled only by the excellence of his Judgement, his unvarying and steady defense of the cause of Justice and truth, his unwearied assiduity in public service, and the crowd of envious and busy detractors, who have only served to illustrate the purity of his character… his purposed departure from this Territory throws a gloom over their prospects, and causes the same emotions as when a child is about to be deprived of the presence of a beloved father…”

More than likely the General wrote it himself for the petitioners’ signatures, as it has that “Wilkinsonian” style of expression. If Wilkinson wasn’t going to return to St. Louis, then the petitioners wanted Joseph Browne to be named the new Governor—whose “integrity of principles” eminently qualified him for the office.

However, Judge John B. C. Lucas, one of three members of the board of land commissioners, Will Carr, the federal land agent, and Silas Bent, the newly arrived federal land surveyor, were all writing very different letters to Washington—and, based on their reports, it was determined that a new administration was needed in Louisiana Territory.

Judge Lucas complained that his two fellow land commissioners were meeting at irregular times and places without him and were not keeping proper records. Both men, James Donaldson and Clement Biddle Penrose, were loyal supporters of Wilkinson; in addition, Penrose was Wilkinson’s nephew. Lucas was refusing to confirm large land claims which greatly exceeded the legal limit of the 800 arpents granted to settlers under Spanish law.

Under Spanish rule, very few completed land titles had been established, as the process was long and difficult. Then there was the two year period from 1801-1803 when France had secretly owned Louisiana. In the old days, local residents hadn’t much cared about legal niceties. Most French villagers had three kinds of land: residential lots in town, grazing land for their animals, and agricultural lots in the common fields. They simply agreed among themselves about working claims in the lead mine district. With the advent of American land speculators, settlers, and the land claims commission, there was a great rush to acquire titles. The process was exceedingly slow and aggravating for both large and small land claimants.

Judge Lucas, a friend of Albert Gallatin, the Secretary of the Treasury, doggedly insisted on following the letter of the law. Will Carr, the federal agent for the lead mine district—who was a friend of Meriwether Lewis’s—supported Judge Lucas in his opposition to the large land claimants. The new land surveyor, Silas Bent (father of the famous Bent Brothers in the southwestern fur trade), reported missing and altered land records to his superiors in Washington.

By January, 1807—after Lewis had reached Washington—President Jefferson had had enough. He wrote to Albert Gallatin that he “had never seen such a perversion of duty as by Donaldson & Penrose” and fired Donaldson, who was also the Registrar of Land Titles. Before they had left St. Louis, Judge Rufus Easton had asked Lewis and Clark to inspect the land records and inform the administration about the “innumerable alterations and forgeries!” Since territories were administered by the federal government, both land titles and the soon to enacted mineral leasing rights for the lead mine district were subject to congressional politics and approval.

LEWIS AND CLARK LEFT FOR WASHINGTON in late October. The group traveling together was a large one, consisting of Lewis and his dog Seaman; Clark and his slave York; Chief Big White and his wife and son; the Chief’s interpreter Rene Jessaume and his wife and two children; two members of the expedition, Sgt. John Ordway and Private Francis Labiche, who came along to help out; and Indian Agent Pierre Chouteau escorting a delegation of six chiefs from the Arkansas band of the Osage. Peter Provenchere was also most likely in the group.

The group would split up in Kentucky. Chouteau took the Osage Chiefs to Washington via the Ohio River, heading north. Big White and his group, accompanied by Ordway and Labiche, remained with Meriwether Lewis.

Lewis and Clark enjoyed the hospitality of the extended Clark family in Louisville. On November 8th, a dinner party was held at Locust Grove, the home of Clark’s sister Lucy and her husband William Croghan. Now a National Historic Landmark, Locust Grove became the home of their brother General George Roger Clark during the last years of his life. William Clark remained in Louisville until December 15th, but Lewis and his group traveled south on the Wilderness Road through Kentucky to the Cumberland Gap, the historic gateway of the Alleghany Mountains.

AFTER PASSING THROUGH THE GAP, Lewis, at the request of local citizens, made a survey of the latitude of the boundary line between the states of Virginia and North Carolina. The line, known as the Walker Line, lay a couple of miles east of the Gap. He reported on November 23rd that the boundary was “nine miles and 1,077 yards North of its proper position,” giving the state of Virginia those extra miles—a nice present to his home state.

Upon arriving at his mother’s house in Charlottesville, Lewis found a letter waiting for him from the President urging him to pay a visit to nearby Monticello with Big White and the others even though Jefferson was in Washington. Jefferson was preparing a “kind of an Indian Hall” at Monticello, displaying artifacts from the Mandans and other Indian tribes and he wanted Lewis and Big White to see it. By December 28th, Lewis and his party had reached Washington.

Clark would arrive in Washington about two weeks later, missing a party held in their honor on January 14th. Clark spent the holidays at Fincastle, where another party had been held on January 8th. He was courting Julia Hancock and obtained her family’s consent that they would be married one year later, in January, 1808. Julia, who was born November 21, 1791, had just celebrated her 15th birthday; Clark was 36 years old—a not uncommon arrangement in those days.

BACK IN ST. LOUIS, JOHN SMITH T. was preparing to go down river with 12,000 pounds of lead to join the Aaron Burr conspiracy. Lead was used to make bullets, a vital necessity for any invasion of Mexico. Colonel De Pestre, Burr’s chief of staff, had come to St. Louis in October, offering commissions in the new army. A disgusted Auguste Chouteau threw the commission in the fire when it was offered to him.

John Smith T. (the “T” stood for Tennessee); Joseph Browne’s son in law, Robert Westcott; Dr. Andrew Steele, and the Sheriff of Ste. Genevieve, Henry Dodge, set out to join Burr with their cargo of lead, but upon reaching New Madrid, they learned about the President’s proclamation of November 27th declaring Burr’s expedition illegal, and they abandoned their plans. When they got back to Ste. Genevieve, Judge Otho Shrader—a friend of Meriwether Lewis’s—had Smith T. and Dodge arrested on charges of treason. After Dodge was arrested, he beat up nine of the grand jury members, and Smith T. threatened to kill Shrader if he tried to arrest him—ending the matter of arrest for both men.

Smith T. was a relative of General Wilkinson. His mother’s name was Lucy Wilkinson Smith; the family came from Essex County, Virginia near Wilkinson’s birthplace in Calvert County, Maryland. Smith T. was infamous as a killer; he was reputed to have killed 15-20 men in duels. He was a small man, who usually dressed in heavily fringed and decorated buckskin shirts and doeskin pants. He always carried four pistols, one dirk (a dagger), and a rifle called “Hark from the Tombs.” Wilkinson appointed Smith T. a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas in Ste. Genevieve, where he heard his cases fully armed.

John F. Darby, the Mayor of St. Louis in 1835, said of John Smith T. that he was:

“as polished and courteous a gentleman as ever lived in the state of Missouri, and as mild mannered a man as ever put a bullet in a human body.”

Smith T. was a major land speculator in the southeastern United States. He had participated in the Yazoo land frauds, owning the northern half of the state of Alabama among other large land holdings. He moved to Missouri to speculate in the lead mine district, purchasing a wild card “floating claim” to 10,000 arpents, giving him the right to claim about 13 square miles of land wherever he wanted. He would send in armed men to illegally seize working claims, and employ lawyers to contest these claims in court.

He was up against Moses Austin (the father of Stephen Austin, the founder of Texas). Austin was a lead mine operator from Virginia, who introduced a new smelting technique, a reverberatory furnace, to the lead mine district south of St. Louis. Austin proposed paying taxes on minerals dug from the land, and to provide smelting services to the government. Captain Amos Stoddard had estimated the value of the lead mine district as being able to pay off the fifteen million debt for the purchase of Louisiana within a few years. It was the richest known deposit of lead ore in the world, and was reserved as public land under the new American government.

John Smith T., however, wanted to use the lead for bullets for an invasion of Mexico. If the invasion had proceeded as planned, many volunteers would have come from the St. Louis area. Both Moses Austin and John Smith T. employed private armies and lawyers to defend their land claims in the lead district’s “Mineral Wars.”

MERIWETHER LEWIS WAS APPOINTED the new Governor of Louisiana Territory on March 3, 1807. William Clark received appointments as Agent of Indian Affairs for Louisiana and Brigadier General of the Territorial Militia. On the same day, Congress passed the Lead and Salt Leasing Act of 1807, placing both the lead and salt petre mines under 3 year leasing provisions.

Lewis had to remain on the east coast, finishing up government paperwork and making arrangements for the publication of the expedition journals. He wrote to William Clark on March 13th, sending Clark’s commission as Brigadier General to him at Fincastle in care of Robert Frazer, a member of the expedition. Frederick Bates, who had been appointed the new Territorial Secretary, would serve as Acting Governor until Lewis arrived in St. Louis. Both Clark and Bates arrived in St. Louis in late April. Lewis wrote that Clark and Bates should:

“… take such measures in relation to the territory as will be best calculated to destroy the influence and wily machinations of the adherents of Col. Burr. It is my wish that every person who holds an appointment of profit or honor in that territory and against whom sufficient proof of the infection of Burrism can be adduced, should be immediately dismissed from office, without partiality favor or affection, as I can never make any terms with traitors. Mr. Robert Waistcoat, son in law to Secretary Brown, Col. John T. Smith and Mr. Dodge sherif of the district St Genvieve are high implicated and there is good reason for believing that Mr. Brown himself might be sensured without injustice.”

LEWIS WAS IN PHILADELPHIA from April to July, visiting with old friends, meeting girls, and reporting about their travels and discoveries to the mentors who four years earlier had helped prepare him for the expedition. He engaged a publisher, and issued an advertising prospectus for the journals. He attended the monthly meetings of the American Philosophical Society; arranged for the plant specimens to be described and sketched; and gave bird specimens to his friend Alexander Wilson to paint.

Lewis probably came to Philadelphia accompanied by Pierre Chouteau and the Osage Indians, and Ordway, Labiche, Provenchere, and Big White’s party, because the French artist Charles St. Memin sketched profiles of Lewis, Big White and his wife, Yellow Corn, and an Osage warrior with the aid of his physiognotrace. (Two of the portraits are seen on pp. 265–66.) The Indians were on their way back home, stopping at several cities en route.

Lewis sat for his famous portrait by Charles Willson Peale—the one that matches the portrait of William Clark, whose portrait was painted by Peale in 1810 (p. 284). Peale had a museum on the second floor of Independence Hall, where he displayed the artifacts collected by Lewis and Clark, and where the little prairie dog and magpie bird captured by Lewis and Clark were living. Jefferson had sent them to Peale, writing that the burrowing squirrel was a “most harmless and tame creature.”

While Lewis was in Philadelphia, Peale was busy mounting and sketching the animal specimens they had collected. Later that year he created a life size wax figure of Captain Lewis to display in his museum; it was dressed in a fringed buckskin outfit, and wearing the tippet or shoulder cape decorated with 140 ermine skins given to Lewis by Sacagawea’s brother, Cameahwait, the Chief of the Shoshone. Lewis called it the most elegant Indian clothing he had ever seen. (See portrait, p. 268.) Springtime in Philadelphia must have been delightful, offering a few months of pleasure and intellectual companionship before Lewis returned to Washington in July.

MEANWHILE, BURRITES IN ST. LOUIS were not happy with the change of government. Robert Frazer, a member of the expedition, who had been supplying information about the Burrites in St. Louis, wrote to President Jefferson from Henderson County, Kentucky on April 16, 1807:

“At Breckenridge court house I was informed of a number of inquiries that some of the party (dispatched to overtake & wrest from me my papers) had been making relative to my business at Washington… I also learned from a gentleman of high respectability, directly from St. Louis that Colo. John Smith (T) will not suffer himself to be taken by the civil authority; but has threatened and reviled me with the harshest and most bitter epithets.

From this man’s character as a desperado & from the servility of a vile and desperate junto of which he is the head, I really think I am in no small danger of assassination, or some other means of taking me off.

I delivered the commission with which I was charged to Genl. Clark at Fincastle. He could not travel as fast as I did and therefore advised me to proceed as quick as possible. Whatever may be the fate I shall meet with, I have the […] consolation to that I have been […] true to my country. And whatever may be the temptation I trust I shall perish sooner than prove otherwise.”

Frazer went on to write that his friends told him to ride for his “personal safety” by way of Vincennes.

Frederick Bates, the Acting Governor, wrote to Jefferson on May 6th that Colonel John Smith T. “had been removed from all his offices civil and military” and other known Burrites had also left office. However, he believed Ste. Genevieve Sheriff Henry Dodge to be “young and innocent.” Dodge went on to be come the first Territorial Governor of Wisconsin in 1836, justifying Bates’s faith in him.

RETURNING THE MANDAN DELEGATION to their homes in North Dakota was Clark’s first priority. Originally it was intended that Ensign Nathaniel Pryor and 14 soldiers would escort the Mandan group, together with a group of 32 traders led by Auguste Pierre Chouteau, Pierre’s son, back to the Knife River Villages. Then 15 Sioux warriors turned up in St. Louis with trader Pierre Dorion; and it was decided to add the Sioux and Dorion’s trading group, and an additional military escort, to the return expedition. Big White thought it would be helpful to travel together. Altogether there were between 102 or 108 people, including 32 Indians—18 men, 8 women, and 6 children. Three former members of the Corps of Discovery were part of the expedition: Ensign Nathaniel Pryor, George Shannon and, most likely, Joseph Field.

On September 9th, they met with unexpected trouble when they arrived at the picketed Arikara earth lodge villages, guarding both sides of the Missouri River in South Dakota. They learned the Arikara were at war with the Mandans, and were still upset their chief had died while visiting Washington the year before. They were traditional middle men on the Upper Missouri, trading their crops with Indians who hunted.

Manuel Lisa and his trading group, including other former members of the Corps of Discovery, had passed the Arikara Villages a few weeks earlier. The Arikara and their Sioux allies had looted them of half their trade goods, and determined to kill them on their return. Lisa told them that Pryor’s trading party would be along to supply them with more goods.

The Arikara were going to allow Pryor’s boat carrying the Indians and soldiers to continue on, but they wanted the boat with trade goods to stay. 21 year old Auguste Chouteau was not willing to part with his goods on unfavorable terms—he offered to trade only half of them, and refused to give any presents. A council was attempted and the two interpreters were on shore, when a battle began.

There were 650 Arikara and Sioux warriors—all armed with guns—when shots were fired. The battle continued for about an hour, with fighting on both sides of the river. Chouteau lost 4 men—one was still alive, but mortally wounded. He had six more wounded. Pryor had three wounded, including George Shannon, who eventually lost his leg due to this encounter, and would wear a wooden peg leg for the rest of his life. The expedition retreated to St. Louis, and it would be two years before they tried again to return the Mandan delegation to their villages. Nathaniel Pryor ended his report to Clark with the observation that:

“A force of less than 400 men ought not to attempt such an enterprize. And surely it is possible that even one thousand men might fail in the attempt.”

Two years later Meriwether Lewis as Governor would be judged harshly by the bureaucrats in Washington, because they didn’t understand, or care about, the difficulties in returning the Chief to his home.

AARON BURR’S TRIAL FOR TREASON was held in the Virginia State House in Richmond, Virginia—in the same Hall of Delegates where Meriwether Lewis’s bust would be placed in 2008. The trial began on May 22, 1807, presided over by the Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall.

General Wilkinson finally arrived after a long delay; and on June 15th, behind closed doors, a grand jury began questioning him and 47 other witnesses regarding the General’s relationship with Aaron Burr. The General talked for four days himself. No record was kept of their testimonies. But by a vote of 9 to 7, Wilkinson escaped indictment for not reporting knowledge of a treasonous plot (“misprision of treason”).

The jury based its decision on the fact that the overt act of treason was supposed to have been committed on Blennerhassett’s Island, and that General Wilkinson had not been not present. The foreman of the grand jury, Congressman John Randolph of Roanoke, Virginia, who detested Wilkinson, wrote to a friend:

“The mammoth of iniquity has escaped…

Wilkinson is the only man I ever saw who is from the bark to the very core a villain. The proof is unquestionable; but, my good friend, I cannot enter upon it here. Suffice it to say that I have seen it, and that it is not susceptible of misconstruction.”

The problem was that if Wilkinson was indicted, he would be viewed as bearing the greatest responsibility for the plot because of the widespread suspicion that he was a pensioner of Spain. Wilkinson’s indictment not only would discredit Jefferson’s administration, it would also shift the blame from Burr. Above all else, Jefferson wanted to permanently destroy Burr’s dreams of establishing a new empire.

Major James Bruff had come from St. Louis in March to warn the Secretary of War General Henry Dearborn about Wilkinson being a pensioner of Spain and an accomplice of Burr. The Secretary told the Major that although the General had recently lost favor with the administration, his energetic actions in New Orleans had restored him to favor. He added:

“that after the actual bustle was over there might perhaps be an inquiry, but meanwhile, Wilkinson must and would be supported.”

This, in fact, did happen. Wilkinson underwent a military court of inquiry in 1808, two congressional hearings in 1810, and two military courts martial in 1811 and 1815. However, he was cleared in all of these investigations.

The grand jury did present bills of treason and high misdemeanor against Aaron Burr, Harmon Blennerhassett, and four others. The trial would begin on August 3rd. Meriwether Lewis arrived back in Washington on July 15th, and attended the trial as an observer for President Jefferson, though neither he nor the President left any paper trail. The jury was seated on August 17th.

The Constitution of the United States states that:

“no person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court.”

The Chief Justice ruled on the last day of August that no testimony regarding Burr’s conduct elsewhere, or afterwards, could be admitted as evidence. The case was dependent upon two witnesses testifying they had witnessed an overt act by Burr within the jurisdiction of the court hearing the case, that is, in the state of Virginia. (At this time, Blennerhassett Island in West Virginia was still a part of Virginia.) The jury delivered a verdict of “not guilty” on September 1st.

President Jefferson demanded that the testimony of the trial, which had not been recorded, be put in writing in order to submit it to Congress; and that no witness would be paid or allowed to leave until their testimony was taken. So the Burr trial now switched to the charge of high misdemeanor and continued until October 19th with testimonies being recorded. If Aaron Burr couldn’t be convicted of treason, then Jefferson wanted to impeach John Marshall. However, once it became apparent that Wilkinson’s involvement would ruin any chance of impeachment, the matter was dropped and all further charges were not pursued.

Burr’s reputation was solidly ruined—at least in terms of running for public office. He left the country, and for four years tried unsuccessfully to persuade the British government and then the French government to back his plans for an invasion of Mexico. He returned to New York, and continued his practice of law until his death in 1836. Other plans for an invasion and the revolutionizing of Mexico went on without him.

Meriwether Lewis most likely spent his spare time during the three month trial writing a very long report entitled:

“Observations and reflections on the present and future state of Upper Louisiana, in relation to the government of the Indian nations inhabiting that country, and the trade and intercourse with the same.”

It was a detailed and thoughtful analysis of the relationships of the Indians tribes with Spanish and British traders; and what Lewis would recommend as the new Governor of Louisiana Territory and Superintendent of Indian Affairs.