Alexander Bay is the last town on the West Coast before you cross into Namibia, and is part of South Africa’s only true desert biome.

Successful oyster farming is a good sideline business at Alexander Bay.

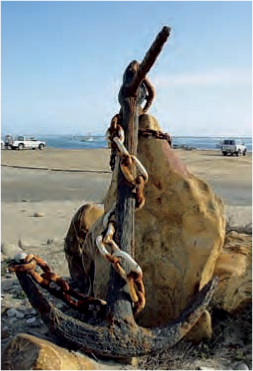

Up here in Alexander Bay, on the Namibian frontier, you are in a world that few people ever see. Wind-lashed beaches littered with twisted driftwood logs, the pounding onslaught of the Atlantic Ocean, the ghosts of ever-patrolling diamond cops, homing pigeons with dodgy agendas and, just in case you were hungry, the cheapest, freshest little oysters on Earth.

Alexander Bay is so very far away from the glittering windows of Tiffany’s or the New York Diamond Dealers Club on West 47th Street, the Japanese jewellery houses of the Ginza in Tokyo or No. 17 Charterhouse Street in London, where more than 80 per cent of the world’s diamonds pass through on their way to the ring fingers and elegant necks of lucky ladies.

And yet, the sweet little Orange River diamonds from the Alexander Bay fields have been adding a glint to lovers’ eyes since the late 1920s. The area north and south of the Mother River’s mouth is one of the world’s treasure houses of fabulous, naturally polished high-grade diamonds. The Namas, Bushmen and Strandlopers who walked its shores centuries ago used to pick the diamonds up as they lay glinting in the sands and give them to their children as toys.

Arguably the most colourful character to have walked these ancient diamond beds was one Fred Cornell, whose prospecting nose twitched every time he ventured up into the Richtersveld. And like the copper miners who first worked here, Fred must have literally walked on diamonds without seeing them.

Imagine you’re Fred back then, sitting on a lonely spot up on the Orange River, having a quiet smoke in the moonlight. Suddenly, there’s the distant sound of a concertina. You go back to the campfire to discover your travelling partner being entertained by a grinning Ovambo wearing a full German colonial army uniform, right down to elastic-sided boots with spurs, heaving away merrily at his concertina, having just appeared out of the black night as if from nowhere. With him are two youngsters, capering away to the music at the fire.

The Alexkor mining area has been scoured for diamonds, leaving scars but also untouched parts.

Fred gives them tobacco and is mildly amused. On they play, apparently tireless. Pretty soon it’s past everyone’s bedtime, but still the concertina continues.

“At last I had to turn out of my blankets and go for them with a sjambok,” he writes in his classic travel book, The Glamour of Prospecting. “Then only did they quit, and I turned in again. But I had got a big thorn in my foot, and when I had got that out a scorpion got into my bed, and objected to my being there. Altogether a nice, quiet, idyllic night by the river ...”

The tour of the mining area (organised in advance) begins at the Alexander Bay Mine Museum.

“The diamonds, washed down the Orange River, mostly lie in a sediment of fossilised oyster shells,” explains the museum curator and tour guide, Helené Mostert. “To get to this sediment, you have to go through as much as 40 metres of sand and calcrete. Then you get to the gravel on the bedrock, which bears the diamonds.”

“They search for diamonds out at sea and on land here, and the divers share their profits with Alexkor,” Helené says as we sign the indemnity forms. She tells us what not to take in: no cigarette lighters, lipstick, Lip Ice, cellphones, skin cream and, of course, no pigeons. A pigeon-club scam (complete with tiny harnesses to carry smuggled diamonds) was uncovered some years ago, and these tame feathered friends are no longer welcome in Alexander Bay airspace.

Alexander Bay society used to be divided into binnekampers and buitekampers (people who lived inside the restricted area and those who were outside the fence). Before leaving the area for a weekend pass, binnekamp families and their possessions were thoroughly searched. Diamond smuggling in Namaqualand has always been as natural as truffle-sniffing in the south of France.

Namaqualand is a vast, barren area of little more than 120 000 souls, a place that gets a total of 50 millimetres of rain each year. That’s about equal to two or three Johannesburg thunderstorms.

“God didn’t give us rain – He gave us diamonds” is the old Namaqualand philosophy. And, according to writer Pieter Coetzer in his excellent book Bay Of Diamonds, many locals openly admitted to illegally dealing in the stones.

Alexander Bay is one of the few natural harbours here, and is used almost exclusively by diamond boats.

But at Alexander Bay, it’s still taboo to swing your tongue too freely around the word “diamond”. If there’s the slightest bit of suspicion about you and your character, you’re packed out of the village before the morning paper arrives from Springbok.

Young Ernest from Pampierstad near Kimberley is assigned to be our guard, to ensure we don’t suddenly bend down and slip a likely looking stone somewhere secret. In the company of Ernest and Helené we drive through the old, Gothic-grey mining complex, a rusted dreamscape scoured by sand, wind, fog and rain over the past eighty years. A lot of rehabilitation is still to be done out here, but, ironically, the mining operations have left some pristine areas as well. We come across beautiful stretches of stark coastline that are home to colonies of seals and cormorants, with the occasional spotting of jackals, oryx and ostriches.

The harbour master, Alvin Williams, says that although his business is mainly with the little diamond boats moored below his office, a Chinese fishing trawler in distress was once allowed into these waters.

“It ran aground and caught fire,” he says. “They couldn’t speak English, and I had to communicate with them that they could not walk around here – and they could definitely not pick anything up.”

Alvin Williams and his family love the stillness of Alexander Bay.

“This place lets your mind wander. You can relax at last.”

For lunch we stop over at the local oyster farm and feast on the sweetest little oysters, which are sold to the locals for a pittance. Nearly three million oysters are being cultivated here in dams, fed constantly by the cold West Coast upwellings. We also hear about the legendary crayfish of Alexander Bay and suddenly the lustre of diamonds dims.

After a few hours of driving across the dunes of the diamond fields, we return to the security clearance area for a long session of interleading rooms, smoky mirrors, X-ray searches and pat-downs. Obviously, our protests of innocence and open, honest faces are not good enough for the eagle-eyed security staff of Alexkor.

Oom Tommy takes out his fiddle and plays a mournful rendition of “Amazing Grace” in the middle of the street.

“Don’t worry,” says Helené, as we nervously entered the search area. “Whatever happens in there, you will get out ...”

We speak to local residents of Alexander Bay. One of them, Oom Tommy Thomas, takes out his fiddle and plays a mournful version of “Amazing Grace” for us in the middle of the street outside his home.

“Before I came here in 1990, I discussed the matter at length with the Lord,” he says. And then he tells us that the Nama of the Richtersveld will inherit Alexander Bay and its riches one day.

He might well be right. The Nama community, along with the Basters from further south, have lodged a land claim with the South African government. The Nama, many of them simple goatherds who scratch a living out of the scrub desert, stand to be massively enriched by a 2003 court ruling, which gives them the right to claim their traditional lands back. When this will happen and how exactly it will translate into riches for the local community still has to be thrashed out – and, no doubt, many lawyers will be well compensated in the process.

But for now, Alexander Bay is heaven on earth for a select group of hardy individuals such as Etienne Goosen, who lives with his wife, Nolene, in the old binnekamp. They like the rough-and-tumble feel of the rows of hardy houses and their rowdy inhabitants.

When the Atlantic is calm enough, Etienne spends his time riding waves on the sea and diving for diamonds in its depths.

“When we’re out there, it’s very physical, but the surfing also keeps you fit,” he says. “And when you’re on the boat, it’s really cool. You’re with your mates, chatting and hanging out together. It’s not really like work. The good thing is no one competes – we’ve all struggled at some time. We all know what’s it’s like. And we’re generally incoherent by ten o’clock.” – Chris

A wall of old cocopans and rocks has been turned into a bulwark against the creeping sand near the diamond plant.

Lichen Hill sports a fluffy lichen “lawn” of Teloschistes capensis.

As you drive in towards Alexander Bay, you will notice what looks like a distant pile of oranges to your right.

This is Lichen Hill, an outcrop Mine Museum curator Helené Mostert counts as her favourite place in the world. She is the only one with keys to the gate, and she comes bearing a water sprayer to show the colourful, mist-loving lichens off at their bright, fluffy best.

This far northern node of South Africa is the dry-as-a-cork part of the country’s only true desert biome.

But Lichen Hill, which obtains most of its moisture from the drifting sea fog, is a tiny showcase of the secret botanical wonders of this region. Its orange colour comes from a rare woolly lichen, Teloschistes capensis, which could easily double as lawn on Mars.

The National Botanical Institute has counted 29 species of lichen here – the highest number in Africa in such a concentrated space.

Huddled within it are little plants, some only the size of a button, so cunningly adapted to drought and heat, so brave, that, kneeling before them, I have the urge to pat them and whisper “Well done”. Botanists come from all over the world to marvel at these ingenious, bijou plants that outwit harsh conditions and flower cheerfully each spring.

We are immersed in a water-thrifty world of fat-leafed vygies, stoic stone plants, spiky euphorbias, shy window plants that sink into the sheltering earth and let diffused sunlight play through their translucent cells, lizard’s tail plants that play dead only until rain falls, and Bushman’s candles with their waxy coating and pretty leaves that harden to protective thorns.

Helené tells us of parsimonious daisies that require raindrops to drum hard on a tiny membrane before a capsule pops open and spurts out seeds. But not all. Some seeds are conserved for other rainfall, just in case. Up on Lichen Hill, tomorrow is another day. – Julie

Tiny succulents and lichens around Alexander Bay have adapted to the desert conditions in many ways and rely on sea mist for their moisture requirements.

Namaqualand’s annual expression of joy.

In the spring, the road to Port Nolloth is paved with desert blooms. To get to the sea, you have to cross vast and magical fields of flowers. They begin somewhere east of Springbok in the late winter and pop up all through Namaqualand and the Richtersveld like random outbursts of ridiculously bright, ludicrously colourful expressions of joy. The daisy fields of the Northern Cape. Once you’ve done the great elk migrations of the northern hemisphere and the mass transits of wildebeest across the Serengeti, you seriously need to come to Namaqualand.

Some years all you’ll see is a clump of deep yellow clambering bravely out of a hole in the highway tarmac. Other seasons – depending on the winter rainfall – yield generous expanses of Mother Nature in party mode. The one and only Vincent would have loved to paint in Namaqualand. He would have set himself up at the Goegap Nature Reserve outside Springbok and, bearing palette, paints and wide-brimmed hat (with perhaps a bottle of chilled sweet wine from Upington and some stinky cheese), he would have wandered up into the cheerful hills and had himself a really good time.

Technically, great sweeps of pink and orange mark land that has been disturbed in some way. But this is not the occasion for scientific observations. This is the time of poetry, awe and admiration. Its message: life is short. Enjoy.

And if you have the spunk and the sense of adventure required for the next journey, then drive across the Anenous Pass and the dry coastal desert belt to Port Nolloth, the frontier town that lies in an almost eternal doily of mist.

The most remarkable sound you will hear in Port Nolloth happens dramatically in the shrouded early hours of the morning, when the rest of this rowdy village has gone to sleep. From out there in the treacherous channel comes the tong-tonging of the bell buoy. That sound has been heard for many decades, by the firstcomers who sought copper and now by the diamond divers who occasionally take on the Atlantic in their little “Tupperware” boats with their long suction pipes.

Alfie Wewege grew up in the Eastern Cape but his heart has lain with Port Nolloth for most of his adult life. Once a strapping young diver, then a ship’s cook, Alf lived the heady life of a popular bachelor on Diver’s Row in Port Nolloth, which used to be a motley crooked collection of small homes full of sea gear such as wetsuits, fishing rods, heavy tools, ropes and nets. He left “Port Jolly”, as the village is known by some, to pursue his career in the waters around Madagascar.

He has returned to the embrace of a life he knows, a seaport he understands and friends he loves dearly. This is not a strange phenomenon. Even the divers who make millions often end up back in Port Nolloth. They love their time out at sea, the occasional chance of striking a rich pocket of diamonds, and the long, drawn-out winters on shore, when they hunker down, count their pennies and sometimes have a party that everyone speaks about for weeks afterwards. It’s a sense of outport community, the kind of camaraderie you find up in the icy, fish settlements of Newfoundland and such.

“There’s a separate reality here,” says Geoff Lorentz, one of the legendary local divers, who still heads out in his boat, the Blues Breaker, and takes on the marine terraces when weather conditions permit.

When the Blues Breaker brings its gravel in to the Trans Hex sorting plant, Geoff’s attractive wife, Lara, works as a sorter. For the rest, she raises their children, cooks hearty meals for the crew, waits for Geoff to return and worries when their boat is caught out in foul weather – just like the other Port Nolloth divers’ women. But this steamy little town has its quirky side.

Grazia de Beer, who owns the Bedrock guest houses, recalls a crowd of locals sitting in the bar of the Scotia Inn, watching the only television channel available at the time.

“Suddenly the face of a wanted man appeared on Police File. Everyone turned around slowly to look at the person in question. He simply shrugged and said, “You got me”. He was quietly escorted out to the police station.

“But it’s not all rough here in Port Nolloth,” Grazia adds. “We’ve got a reflexologist and a Reiki expert in town ...”

Captain MS Nolloth arrived here in his boat HMS Frolic in 1854. Then came the “copper heads”, who made for the newly opened mines of the interior. Diamonds were discovered a scant six kilometres south of Port Nolloth in 1926, and the diggers and the prospectors began to stream into town. When the great fields were found up in Alexander Bay just a year later, the fleshpots of Port Nolloth seethed with rebellion after the State restricted access to the area.

In a way, Port Nolloth seethes on. It sits between two huge restricted diamond areas. Sometimes shady deals go down. Sometimes the basic rebellious nature of the last of the African cowboys, the offshore diamond diver, demands a bigger stake in the prize. And sometimes the bitterly cold Benguela Current just brings on a bad mood.

But whatever the day offers, wind, storm, mist or rain, the people of Port Nolloth would rather live here than anyplace else on Earth. And once you hear that “dead hour bell” tong-tonging out in the channel, and you glance out of the window through the mists, you will see the magic of Port Jolly. And perhaps you’ll spot Alfie Wewege out by the boats, having a last smoke and a look out on the unsettled waters of the Atlantic. – Chris

Alfie Wewege has returned to his beloved friends and life at Port Nolloth.

Everything in this little town is focused on the sea and diamonds.

The diamond diving boats are also called “Tupperwares”, or “Tuppies”. The pipes out back are used for sucking diamond-bearing gravel from the sea floor.

Namaqualand’s exuberant plant life ranks it as one of the richest arid areas on Earth.

The sweeping beauty of the Goegap Nature Reserve just outside Springbok.

Not only did God give Namaqualanders diamonds. He gave them daisies as well.

The neatly proportioned Kliphuis (Stone House) near Kleinsee used to belong to farmers before De Beers bought the land, and has a tragic history.

Back in the late 1920s, while diamond fever was sweeping the northern reaches of the West Coast, a teacher called Pieter de Villiers was on another mission. He was building a farm school near the mouth of the Buffels River at a place called Kleinsee (Little Sea). While looking for lime to whitewash the walls, he kicked up a diamond.

There was, predictably, huge excitement. But only a few years later, in 1932, the Great Depression sank the world’s economy into a diamond-indifferent torpor.

Kleinsee Mine on the West Coast was officially closed, but 50 people – male workers, their wives, their children and a small band of domestics – still lived in the little company town.

“The ‘senior staff’, with little work to do, preserved a pretentious exclusiveness,” wrote Peter Carstens, in his book In The Company Of Diamonds, “holding select dinner parties, picnics on the beach and in the veld, and ostentatiously displaying the cars that they could barely afford to run.”

Once the world’s economy ticked up again, diamonds regained their sparkle. Like Alexander Bay, Kleinsee used to be closed to the public, but nowadays you can take a mine tour.

Suddenly, from the rowdy rough and tumble of Port Nolloth, we are in a neat little box-like, litter-free town where people keep to the speed limit.

A video running in the Welcome Centre tells us De Beers is working at keeping the mine going until 2028. After that, we later discover, their exit strategy is to hand over a tidy village with a number of medium-to-small enterprises in place. Mariculture pilot projects to cultivate abalone, oysters and white mussels are being set up.

And they are rehabilitating their mining areas.

“In fifty years’ time, people won’t even know there was a mine here,” we are assured.

Dressed like dude miners, we climb into a bus and drive past the faceless, windowless final processing plant, where no human skin touches a diamond. It’s all done by quarantine gloves and conveyor belts under the constant eyes of many cameras. Not a very touchy-feely kind of process.

One of the hundreds of fishing vessels that have met their end on the stormy West Coast.

The Border, a boat shuttling supplies from Cape Town to Port Nolloth, went down in heavy mist in 1947.

Further along, we come to the bedrock, where diamonds are said to lie. Massive suction units are being used to hoover up the gravel. Our guide, Mariska Theunissen, says the workers here are encouraged not to bend down.

“And if you do, it’s considered very good manners to hold up your hands immediately to show what you picked up.”

We arrive at a 3-kilometre stretch of coastline which hosts up to 400 000 Cape fur seals, part of the world’s largest population of seals. Of late, they have been chomping away at the gannets of Lambert’s Bay and the penguins of Robben Island further south, which has not endeared them to the world at large.

The Main Event of Kleinsee is the dragline, a monster machine that looms above the skyline and needs its own transformer station to power it.

“Every Sunday, when they start it up, the lights all over the town of Kleinsee go dim,” says Mariska. The dragline saves a lot of spadework – its bucket eats 72 tons of soil with every bite.

Back at the Welcome Centre, we ask public-relations man Gert Klopper about Kleinsee’s water sourcing. Most of it comes from the Gariep River these days, he tells us. But they also take water from the nearby Buffels River, which is notoriously brackish.

“Let’s just call it water with attitude,” smiles Gert.

“People get used to the brackish taste,” adds Jackie Engelbrecht, his colleague. “When they leave Kleinsee, some of the older people like to add a pinch of salt to their coffee because they’re so used to the mineral saltiness of the water.”

“And what do people do in their spare time around here?” we ask.

Gert and Jackie enumerate an extraordinary array of clubs – golfing, shooting and angling all feature big in the social life of Kleinsee. So does cycling, because there is no traffic. There is only one suitable tar road though – the one to Koiingnaas. You have the southwester in your face on the way there, but it kindly pushes you all the way home.

A clutch of abandoned ostrich eggs in the dune sand near Kleinsee.

The Piratiny ran aground in heavy weather in 1943 – or came to grief because of a German torpedo – and now lies, still relatively intact, in two large pieces.

An irrepressible Mesembryanthemum crystallinum grows on the rust surface of the wreck of the Border.

We have a prawn supper drenched in garlic at the Houthoop Guesthouse. The next morning, wherever we go reeks of France. Floors Brand is on hand to guide us on a great field trip through the unmined De Beers land.

“Sorry about the garlic,” I say to Floors.

“Don’t worry,” he says. “I had garlic on my mashed potatoes last night.”

The tall, grey-haired Floors is the retired Estate Manager for Kleinsee. Only part of the 400 000 hectares owned by De Beers in these parts is mined. The rest of it is dune lands, shipwreck coast, succulent gardens, mystery stories, smugglers’ secret little inlets, old legends, seaside hideaways and, at this time of the year, hundreds of bonking tortoises which have suddenly discovered a dash of speed.

This area has dozens of wild bays, where drifts of plovers run up and down at the edge of the breaking waves. Scouring winds drive the warmer water near the surface off so that the icy waters deeper down are forced up, carrying plankton and nutrients with them.

“This is the Benguela Current, what they call The Upwelling,” says Floors. “This is what makes the waters off the West Coast so rich.” This is, obviously, why so many seals regard the area as prime coastal property.

We wander up and down the coast and into the Strandveld in Floors’s 4x4, eventually coming upon an old ruin of a cottage that looks like a postcard from the Scottish Hebrides. It is appropriately called Die Kliphuis (The Stone House) and has a tragic history – some children died from mysterious poisoning here.

On the way back to the vehicle, Floors calls us over to observe the minute differences between two species of gazania.

“This is why it’s best to appreciate Namaqualand on your knees,” says Floors. What we like to call “a belly safari”.

We find the wreck of the Arosa, a concrete-carrying vessel that some say was run aground on purpose. Then Floors shows us a wreck that carries the rather Disneyesque name of Piratiny, a 5 000-ton Brazilian steamer that foundered off these shores in June 1943 – possibly sunk by a German torpedo.

Weeks after the shipwreck, a heavy storm blew up and left the beaches covered with luggage from (and pieces of) the Piratiny, including a lot of dress materials and bolts of silk. Several months later at the Nagmaal (church communion), all the local children came uniformly dressed in clothes made from the Piratiny flotsam.

Driving through the De Beers game farm, we encounter a number of very preoccupied male angulate tortoises intent on crossing the road at high speed in search of the (obviously angulate) opposite sex. Normally when you shove a wide-angle lens into a tortoise’s face, it withdraws into its shell. Not these. They glare up at Chris like movie stars dealing with paparazzi: if you value your big toe, you’ll get out of my way. – Julie

Above and Below Hondeklip Bay was named after a large stone shaped like a dog, but someone chopped off its “ear” to prospect for copper. In the gigantic storm of 2002, three men died, many boats were wrecked and the jetty was swept away. Hondeklip Bay has a diamond diving fraternity.

Summer, 1855. The old jetty at Hondeklip Bay at low tide. Chained to its piers are three miserable souls, part of a drinking club that tore up the town last night. Their mates are in the local lock-up, also suffering the effects of too much Cape Smoke brandy.

It all begins the day before, and sounds like a damn good idea. The group of men, copper drovers who have battled across the sands from Springbokfontein (now Springbok) with their loads, invest in a 16-gallon cask of brandy and form a drinking circle around it on the beach. At first, there is much merriment. Then they all fall into a deep depression, have another round and become “general disturbances”, making sleep impossible for the few locals.

The magistrate, a large and powerful man called Pillans, is rousted from his bed and emerges from his hut a very angry person. Grabbing torches and a couple of deputies, Pillans soon has the drunken drovers rounded up. He has most of the revellers thrown into the small gaol and the trio that can’t fit in are hauled back down to the beach and chained to the piers. They watch the morning sun through a haze of Cape Smoke and remorse. And there’s also the small matter of rising waters.

We arrive in this strangely named village (Dog Stone Bay?) to be met by a collection of brightly painted little houses, with a ghostly mist descending as we approach the harbour at low tide.

The sea line, only metres away from us, becomes invisible. The cloak of mist lifts slightly to reveal a flotilla of bobbing tuppies with their suction pipes hanging aft like large intestines. Hondeklip Bay has its own mad fraternity of diamond divers.

An ancient mariner of sorts arrives and sits down near us. His name is Ivan Don. By day, he fishes. At night, he is the guard at the old lobster-packing factory, which was closed down more than 20 years ago.

Even the West Coast Upwelling cannot withstand constant overfishing.

“These days, there’s just a couple of roeibakkies (rowing boats) that go out for hotnotsvis, harders and a bit of snoek,” says Ivan.

“Where’s the famous jetty?” we ask.

“A big storm came in 2002 and washed it away,” he replies. “The surge killed three men in a roeibakkie, crossed the road to the Post Office and ruined the petrol pump forever.”

For now, there is the sound of seagulls, the sight of a receding mist line and the prospect of another quiet day in this West Coast hideaway. – Chris

The cloak of mist lifts slightly to reveal a flotilla of bobbing tuppies.