The use of child soldiers is probably the world’s most unrecognized form of child abuse.

—New York Times1

From its very beginning, human warfare has been an almost exclusively adult male domain. The battlefield was an arena generally closed to all others for nearly four millennia.2 Indeed, only within the last few decades have able-bodied adult women even been considered capable of participating in war, and this change is far from widespread.

The exclusion of children from warfare has held true in almost every traditional culture. For example, in pre-colonial African armies the general practice was that the warriors typically joined three to four years after puberty. In the Zulu tribe, for instance, it was not until the ages of eighteen to twenty that members were eligible for ukubuthwa (the drafting or enrollment into the tribal regiments).3 In the Kano region of West Africa, only married men were conscripted, as those unmarried were considered too immature for such an important job as war.4 When children of lesser ages served in ancient armies, such as the enrollment of Spartan boys into military training, at ages seven to nine, they typically did not serve in combat. Instead, they carried out more menial chores, such as herding cattle or bearing shields and mats for the more senior warriors. In absolutely no cases were traditional tribes or ancient civilizations reliant on fighting forces made up of young boys or girls.

The exclusion of children from war was not simply a matter of principle but was pragmatic too, as adult strength and training were needed to use pre-modern weapons. It also reflected the general importance of age in tribal organization. Most traditional cultures relied on a system of age grades for their ruling structures. These were social groupings determined by age cohorts that cut across ties created by kinship and common residence. Such a system enabled senior rulers and tribal elders to maintain command over young—and potentially unruly—subjects. For instance, in the Achioli tribe, in what is now northern Uganda, the system was known as “Lapir.” Not only were children and women not to be targeted by the tribe’s warriors, but clan elders were the only ones who could decide whether to go to war. This acted as an inherent force of stability.5 Today, within this same tribe, the Lapir system has been turned on its head. Over the last decade, the area has become engulfed in conflict, with most of the fighting carried out by abducted child soldiers targeting civilians.

I grew up in a society where the concept of lapir was very strong. Lapir denotes the cleanliness and weight of one’s claim, which then attracts the blessing of the ancestors in recognition and support of that claim.

Before declaring war, the elders would carefully examine their lapir—to be sure that their community had a deep and well-founded grievance against the other side. If this was established to be the case, war might be declared, but never lightly. And in order to preserve one’s lapir, strict injunctions would be issued to regulate the actual conduct of the war. You did not attack children, women or the elderly; you did not destroy crops, granary stores or livestock. For to commit such taboos would be to soil your lapir, with the consequence that you would forfeit the blessing of the ancestors, and thereby risk losing the war itself.…

But today, to paraphrase the poet W. B. Yeats, things have fallen apart, the moral centre is no longer holding. In so many conflicts today, anything goes. Children, women, the elderly, granary stores, crops, livestock—all have become fair game in the single-minded struggle for power, in an attempt not just to prevail but to humiliate, not simply to subdue but to annihilate the “enemy community” altogether. This is the phenomenon of total war.

—OLARA OTUNNU, UN special representative

for children and armed conflict6

Similarly in European history, the exclusion of children was a general rule. However, some male children did play military roles, though not as active soldiers. Boy pages helped arm and maintain the knights of medieval Europe, while drummer boys and “powder monkeys” (small boys who ran ammunition to cannon crews) were a requisite part of any army and navy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The key is that these boys fulfilled minor or ancillary support roles and were not considered true combatants. They neither dealt out death nor were considered legitimate targets. Indeed, Henry V was so angered at the breaking of this rule at the battle of Agincourt (1415), where some of his army’s boy pages were killed, that he in turn slaughtered all his French prisoners, as famously described by Shakespeare.

FLUELLEN: Kill the boys and the luggage! ’Tis expressly against the law of arms: ’tis as arrant a piece of knavery, mark you now, as can be offer’t: in your conscience now, is it not?

GOWER: ’Tis certain there’s not a boy left alive; and the cowardly rascals that ran from the battle ha’ done this slaughter: besides, they have burned and carried away all that was in the King’s tent; wherefore the King, most worthily, hath caused every soldier to cut his prisoner’s throat. Oh, ’tis a gallant King!

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Henry the Fifth7

Even the new mass armies and general mobilization of society that the French Revolution brought about in 1789 did not lead to children serving as soldiers. Rather, children who joined worked exclusively behind the lines, helping women and elderly tend to the wounded.

Perhaps the most well-known use of supposed child soldiers in history is the famous Children’s Crusade in the Middle Ages. Interestingly, the reality is that the crusade was not an actual case of children at war. Instead, it was a march of thousands of mostly unarmed boys from northern France and western Germany who sought to take back the Holy Land by the sheer power of their faith. Crowds of disenfranchised boys, who had been excluded from the prevailing feudal social structure, were inspired by a French peasant boy named Stephen from a village near Vendôme and a German boy named Nicholas from Cologne. The two claimed to have met Jesus Christ, whom they said had given them a plan to succeed at taking back Jerusalem where the adult crusaders had failed. The boys would march to the Mediterranean Sea, which would part for them, and they would continue on to the Holy Land, whereupon the infidels would bow down before their innocence. What actually happened is that while Stephen and Nicholas succeeded in gathering roughly thirty thousand boys, the crowd was robbed and attacked along its way to the Mediterranean. Once there, the sea did not part. Eventually, a small number of the children were able to embark on seven boats provided by local merchants in Marseilles. Two of the boats sank with all lives lost. The other five did not make it to the Holy Land but landed instead in Algiers, whereupon the boat captains sold the children into slavery to the local ruler.8

Another historic myth of child soldiers was the Janissary of the Ottoman Empire. This was a corps made up of Christian captives, often youths rounded up by the civil authorities as a form of tax on non-Muslim families. Separated from their families, they were crafted into an elite group that was answerable only to the sultan. The youths, though, were not deployed until they had gone through a strict program of education, religious instruction, and then military training, thus only until they had become adults. The Janissary evolved into one of the first standing professional armies and thus gave the Ottomans an edge over the Western feudal armies of the period. Because of its gain in power and influence, the Janissary corps soon became a hereditary organization and lost any youth or Christian aspect. In time, it became a primary palace guard rather than a feared army. It was folded by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 because he feared its threat to his power.

Stories of children’s involvement in warfare are also found in American history, all the way back to the fictional Johnny Tremain, who grows from apprentice to patriot during the Revolution.9 While the earliest regulations of the U.S. Army (1802) stated that no person under the age of twenty-one could enlist without his parents’ permission, there was no minimum age if the child had his parents’ consent.10 This meant that a small number of young boys served as musicians, powder monkeys, and midshipmen (teenage gentlemen officers in training) in the nascent American military. In 1813 new rules lowered the age of admission without parental permission to eighteen, but also standardized the roles of those younger with parental permission. The regulations stated that “healthy, active” boys between fourteen and eighteen could enlist as musicians with parental consent. These boys’ musician positions existed until 1916.

The musicians, though, were different from regular soldiers or sailors. The boys were clearly differentiated from active combatants, often by different uniforms. Additionally, U.S. forces were far from reliant on their presence. Their roles still did entail great risk, though, and many conducted themselves with bravery, sometimes going outside their established areas. Perhaps the most notable boy to serve in the U.S. Army was fifteen-year-old bugler John Cook, the only child to ever win the Medal of Honor. At the Civil War battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862), the bloodiest day in U.S. history, Cook was serving as a courier for a Union artillery battery. While running messages to other units, he discovered two unmanned cannons. He then took it upon himself to serve them. Just five feet tall, he single-handedly carried out the job of a four-man gun crew. While he was firing the guns, Union brigadier general John Gibbon spotted him. While it certainly wasn’t the best role for either the boy or the general, Gibbon jumped off his horse and joined Cook in firing the guns until the end of the battle. By the end of the war, Cook had served in more than twenty battles.11

I was fifteen years of age, and was bugler of Battery B, which suffered fearful losses in the field at Antietam where I won my Medal of Honor.… At this battle we lost forty-four men, killed and wounded, and about forty horses, which shows what a hard fight it was.

—JOHN COOK12

Thus, while the rule held that children were not to be soldiers, there were some exceptions in the grand span of history. Small numbers of underage children certainly lied about their ages to join armies, while others like Cook found ways to go outside their designated roles. In addition, a few states sent children to fight in their last gasps of defeat. Perhaps the most notable instances were the Virginia Military Institute cadets who fought at the battle of New Market in May 1864 and the arming of the Hitler Jugend (Hitler Youth) when Allied armies entered Nazi Germany in the spring of 1945. At New Market, Union forces marched down the Shenandoah Valley, hoping to cut the Virginian Central Railroad, a key supply line. Southern general John Breckinridge found himself with the only Confederate force in the area, commanding just fifteen hundred men, so he ordered the corps of cadets from the nearby VMI military academy to join him. Two hundred forty-seven strong (roughly twenty-five were sixteen years old or younger), they waited out most of the battle until its final stages. Then, in a fairly dramatic charge, they overran a key Union artillery battery. Ten cadets were killed and forty-five were wounded. Ultimately, though, their role was for naught. Within the year, the Union would capture the Shenandoah and with it the rest of the Confederacy.13

The Hitler Jugend were young boys who had received quasi-military training as part of a political program to maintain Nazi rule through indoctrination. During most of World War II, the youths only joined German military forces (including the SS, for which they were a feeder organization) once they reached the age of maturity. However, when Allied forces invaded German territory in the final months of the war, Hitler’s regime ordered these boys to fight as well. It was a desperate gambit to hold off the invasion until new “miracle” weapons (like the V-2 rocket and Me-262 jet fighter) could turn the tide. Lightly armed and mostly sent out in small ambush squads, scores of Hitler Jugend were killed in futile skirmishes, all occurring after the war had essentially been decided.14

I swear by God this Holy Oath: I will render unconditional Obedience to the Führer of the German Reich and the people, Adolf Hitler, the supreme commander of the Armed Forces and will be ready as a brave soldier, to stake my life at any time for this oath.

—Oath taken by Hitler Jugend15

In sum, while there were isolated instances in which children did serve in armies or other groups at war, a general norm held against child soldiers across the last four millennia of warfare. The small number of cases were qualitatively different from a general practice, being isolated in time, geographic space, and scope. Moreover, the children were never an integral or essential part of any of the limited number of forces they served in. New Market, for example, was the first and only major battle in all U.S. history to see their use. It involved only 247 boys total, and no other countries in that period rushed to copy the example. All told, the incidents are the exceptions to what the rule used to be.

The nature of armed conflict has changed greatly since these times. The case of Sierra Leone, a small country in West Africa, captures just how much. Sierra Leone is often at the center of the child soldier discussion, not simply because the country has suffered through a terrible civil war that lasted from 1991 to 2001, but because of the prominent role of children in fighting it. In the rebel Revolutionary United Front (RUF) organization that initiated the violence, as much as 80 percent of all fighters were aged seven to fourteen, many of them abducted.16 Moreover, children were brought into the fighting at the very start, not at a later point when adult soldiers ran short, as had been the case in some earlier instances. However, the RUF was not the only group in Sierra Leone to use child soldiers; both the government and its tribal militia allies recruited them as well. The overall total of child soldiers for all the sides is close to ten thousand, putting them in the majority of total fighters in the conflict.

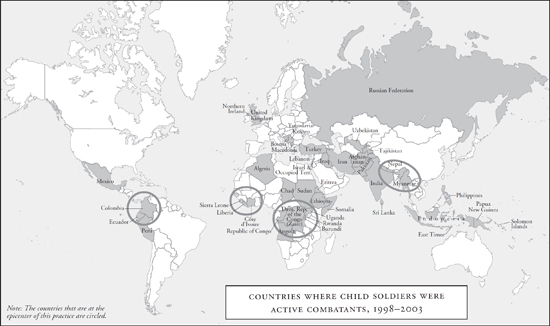

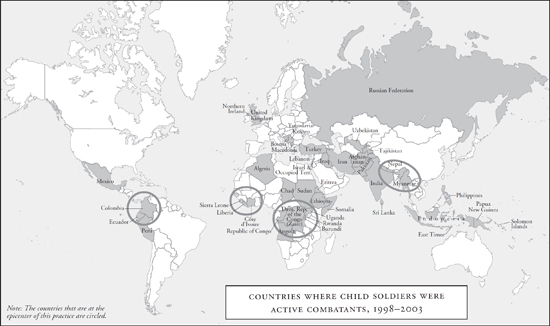

Sierra Leone is no exception, though. By the turn of the twenty-first century, child soldiers had served in significant numbers on every continent of the globe but Antarctica. They have become integral parts of both organized military units and nonmilitary but still violent political organizations, including rebel and terrorist groups. They serve as combatants in a variety of roles: infantry shock troops, raiders, sentries, spies, sappers, and porters. In short, the participation of children in armed conflict is now global in scope and massive in number.

A quick tour around the world reveals the extent and activity of this new practice of war over the last decade.

In the Americas since 1990, child soldiers have fought in Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico (in the Chiapas conflict), Nicaragua, Paraguay, and Peru. The most substantial numbers are in Colombia. There, more than eleven thousand children are being used as soldiers, meaning that one out of every four irregular combatants is underage. They serve on both the rebel side, in the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and National Liberation Army (ELN) organizations, and with the Colombian government’s military and rightist paramilitary groups such as the United Self-Defense Forces (AUC). As many as two thirds of these children fighters are under fifteen years of age, with the youngest recruited being seven years old.17

Child soldiers in Colombia are nicknamed “little bells” by the military that use them as expendable sentries and “little bees” by the FARC guerrillas, because they “sting” their enemies before they know they are under attack. In urban militias, they are called “little carts,” as they can sneak weapons through checkpoints without suspicion. Up to 30 percent of some guerrilla units are made up of children. Child guerrillas are used to collect intelligence, make and deploy mines, and serve as advance troops in ambush attacks against paramilitaries, soldiers, and police officers. For example, when the FARC attacked the Guatape hydroelectric facility in 1998, the employees of the power plant reported that some of the attackers were as young as eight years old. In 2001 the FARC even released a training video that showed boys as young as eleven working with missiles.18 In turn, some government-linked paramilitary units are 85 percent children, with soldiers as young as eight years old seen patrolling.19 There has also been cross-border spillover of the practice. The FARC recruits children from as far away as Venezuela, Panama, and Ecuador, some as young as ten.20

They bring the people they catch … to the training course. My squad had to kill three people. After the first one was killed, the commander told me that the next day I’d have to do the killing. I was stunned and appalled. I had to do it publicly, in front of the whole company, fifty people. I had to shoot him in the head. I was trembling. Afterwards, I couldn’t eat. I’d see the person’s blood. For a week, I had a hard time sleeping.… They’d kill three or four people each day in the course. Different squads would take turns, would have to do it on different days. Some of the victims cried and screamed. The commanders told us we had to learn how to kill.

—O., age fifteen (recruited by FARC at age twelve)21

On the European continent, children under eighteen years of age have served in both British government forces and their opposition in Northern Ireland and on all sides in the Bosnian conflict. As one former Bosnian child soldier, who was fourteen when he enlisted, describes of the fighting, “It was World War I style fighting. There were a lot of mortar attacks, howitzers, and tanks—a lot of armor got involved. Both sides took a lot of casualties from the minefields and snipers … I kind of quit after my dad was injured. I had to take care of my family.”22 However, the majority of child soldiers in Europe have fought in opposition groups farther to the east, serving in Chechnya, Daghestan, Kosovo, Macedonia, and Nagorno-Karabakh. For example, young teens fought in the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in the war against the Serbs in 1997–98. Many children have since joined the other Albanian rebel groups attempting to break away bits of territory from Serbia and Macedonia, serving in both the Liberation Army of Presevo, Medvedja and Bujanovac (UCPMB) and the National Liberation Army. In Chechnya, Russian commanders are now wrestling with the fact that, as the war has persisted, they are faced with younger and younger opposition fighters. As one Russian colonel commented, “In the [separatist] bands there are more and more youths, ages 14–16. They place the mines; they fire at the checkpoints. An adolescent does not even understand what he is being killed for … I think that we will have to create youth labor camps, put them there so they can learn at least something about civilized forms of existence.”23

It is in Turkey, though, where the most child soldiers in Europe are found, in the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK). In 1994 the PKK began the systematic recruitment of children. It even created dedicated children’s regiments. In 1998 it was reported that the PKK had three thousand underage children within its ranks, with the youngest reported PKK fighter being an armed seven-year-old. Ten percent of these were girls.24 The PKK is also known to have recruited children abroad, for example targeting Kurdish émigré kids who were attending schools and summer camps in Sweden.25

Africa is often considered to be at the epicenter of the child soldier phenomenon, with the Sierra Leone case being the most instructive. Armed groups using child soldiers cover the continent and are present in nearly every one of its myriad of wars. The result appears to be an almost endemic link between children and warfare in Africa. For example, a survey in Angola revealed that 36 percent of all Angolan children had either served as soldiers or accompanied troops into combat.26 Similar patterns hold for children in Liberia, which has seen two waves of wars over the last decade. First, Charles Taylor seized power at the head of a mainly youth rebel army in the early 1990s. By the end of the decade, Taylor faced new foes in the LURD and MODEL, rebel groups that also used child soldiers to eventually topple him in 2003. The United Nations estimates that some twenty thousand children served as combatants in Liberia’s war, up to 70 percent of the various factions’ fighting forces.27 Of particular note in Africa is the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda (LRA), renowned, or rather infamous, for being made up almost exclusively of child soldiers. It has abducted more than fourteen thousand children to turn into soldiers. The LRA also holds the ignoble record for having the world’s youngest reported armed combatant, age five.28

Don’t overlook them. They can fight more than we big people … It is hard for them to just retreat.

—Liberian government militia commander29

The areas where child soldiers have been present read like a master list of the continent’s worst zones of violence. In Somalia, boys fourteen to eighteen regularly fight in warlord militias. In Rwanda, thousands of children are thought to have participated in the 1994 genocide. For example, one rehabilitation camp alone housed some 486 suspected child genocidaires. The boys were all younger than fourteen when they allegedly took part in the mass killings of thousands.30 Across the border, in the ongoing fighting in Burundi, up to fourteen thousand children have fought in the war, many as young as twelve.31 Indeed, at the start of the war, Hutu rebel groups sent between three thousand and five thousand children to training camps in the Central African Republic, Tanzania, and Rwanda. Since then, refugee and street children in these countries and Kenya have also been recruited for the fighting in Burundi. Similar practices prevail in fighting to the east in Congo-Brazzaville and Côte d’Ivoire (three thousand estimated child soldiers), while to the north, large numbers of Ethiopian youths fought in their country’s war with Eritrea. Despite Ethiopian government claims that it had no child soldiers, hundreds of its POWs taken by the Eritreans were found to be between fourteen and eighteen. At the same time, the Ethiopian government faces an internal rebellion from the Oromo Liberation Front, which is also alleged to have recruited children. Two twenty-two-year-old members of the OLF recently testified that they had been fighting in the organization since they were eleven years old.32

Child soldiers have also become a common feature of the continent’s largest conflict, the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The fighting in what used to be Zaire began in 1996 with the revolt led by Laurent Kabila. His army had some 10,000 child soldiers between the ages of seven and sixteen.33 As the war spread, it involved armies from eight different countries and a multitude of rebel groups. It continues today. Estimates are that there are presently between 30,000 and 50,000 child soldiers in the DRC—as much as 30 percent of all combatants.34 In Bunia district, a particularly nasty war zone where European peacekeepers were deployed in summer 2003, they make up between 60 and 75 percent of the warring militias (8,000 to 10,000 in the Ituri town alone).35

Congolese child soldiers were known as kadogos, “little ones” in Swahili. They have been so prevalent that they even served in Kabila’s Presidential Guard. Indeed, when Kabila was later assassinated in January 2001, many held his unruly kadogos responsible. The ultimate blame fell on a boy serving as his bodyguard, who was shot during the ensuing firefight.36

The Middle East is another area where child soldiers have become an integral part of the fighting. Children today are engaged in fighting in Algeria, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Iran (as part of rebel groups now fighting against the regime), Iraq, Lebanon, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Yemen. These include children younger than fifteen serving in a number of radical Islamic groups. Young teens are also at the center of fighting in Palestine, making up as much as 70 percent of the participants in the intifada. The response by the Israeli military has been to change its rules of engagement. As one army sharpshooter stated, “Twelve [years] and up is allowed. He’s not a child anymore. That’s what they tell us.” The outcome is that more than 20 percent of those killed in the intifada have been seventeen and under.37

The first modern use of child soldiers in the region was actually during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s. Iranian law, based on the Koranic sharia, had forbid the recruitment of children under sixteen into the armed forces. However, a few years into the fighting, the regime began to falter in its war with its neighbor, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. So it chose to ignore its own laws, and in 1984, Iranian president Ali-Akbar Rafsanjani declared that “all Iranians from twelve to seventy-two should volunteer for the Holy War.”38 Thousands of children were pulled from schools, indoctrinated in the glory of martyrdom, and sent to the front lines only lightly armed with one or two grenades or a gun with one magazine of ammunition. Wearing keys around their necks (to signify their pending entrance into heaven), they were sent forward in the first waves of attacks, to help clear paths through minefields with their bodies and overwhelm Iraqi defenses. Iran’s spiritual leader at the time, Ayatollah Khomeini, delighted in the children’s sacrifice and extolled that they were helping Iran to achieve “a situation which we cannot describe in any other way except to say that it is a divine country.”39

While the child-led human wave attacks were initially very successful, they soon bogged down as the Iraqis adjusted by developing prepared defenses and using chemical weapons. All told, some 100,000 Iranian boy soldiers are thought to have lost their lives. The story of those who did not die is equally tragic. Several hundred Iranian boys were captured. However, when the Red Cross tried to arrange a repatriation program, the Ayatollah Khomeini sent a chilling message that made it clear that all the Iranian boy soldiers were meant to die. In rejecting the Red Cross’s proposal to return the boys home, he stated, “They are not Iranian children. Ours have gone to Paradise and we shall see them there.”40

Iraq, in turn, enrolled child soldiers in that conflict, and more recently, under Saddam Hussein, built up an entire apparatus designed to pull children into conflict. This included the noted Ashbal Saddam (Saddam’s Lion Cubs), a paramilitary force of boys between the ages of ten and fifteen that was formed after the first Gulf War and received training in small arms and light infantry tactics. More than eight thousand young Iraqis were members of this group in Baghdad alone.41 During the recent war that ended Saddam Hussein’s regime, American forces engaged with Iraqi child soldiers in the fighting in at least three cities (Nasariya, Karbala, and Kirkuk).42 This was in addition to the many instances of children being used as human shields by Saddam loyalists during the fighting.43 A number of anti-Saddam paramilitary groups that emerged in the country also utilized children. For instance, the Free Iraqi Forces that were linked to U.S.-backed exile leader Ahmed Chalabi also recruited children as young as thirteen.44

The implications of this training and involvement in military activities by large numbers of Iraqi youth were soon felt in the guerrilla war that followed. Beaten on the battlefield, rebel leaders sought to mobilize this cohort of trained and indoctrinated young fighters. A typical incident in the contentious city of Mosul provides a worrisome indicator of the threat posed by child soldiers to U.S. forces. Here, in the same week that President Bush made his infamous aircraft carrier landing heralding the end to the fighting, a twelve-year-old Iraqi boy fired on U.S. Marines with an AK-47 rifle.45 Over the next weeks, incidents between U.S. forces and armed Iraqi children began to grow, to the extent that U.S. military intelligence briefings began to highlight the role of Iraqi children as attackers and spotters for ambushes. Incidents with child soldiers continued into the guerrilla campaign that followed, ranging from child snipers to a fifteen-year-old who tossed a grenade into an American truck, blowing off the leg of a U.S. Army trooper.46

In the summer of 2004, radical cleric Muqtada al-Sadr directed a revolt that consumed the primarily Shia south of Iraq, with the fighting in the holy city of Najaf being particularly fierce. Observers noted multiple child soldiers, some as young as twelve years old, serving in Sadr’s “Mahdi” Army that fought U.S. forces. Indeed, Sheikh Ahmad al-Shaibani, Sadr’s spokesman defended the use of children, stating, “This shows that the Mahdi are a popular resistance movement against the occupiers. The old men and the young men are on the same field of battle.47

Last night I fired a rocket-propelled grenade against a tank. The Americans are weak. They fight for money and status and squeal like pigs when they die. But we will kill the unbelievers because faith is the most powerful weapon.

—M., age twelve48

The overall numbers of Iraqi children involved in the fighting are not yet known. But the indicators are that they do play a significant role in the insurgency. For example, British forces have detained more than sixty juveniles during their operations in Iraq, while U.S. forces have detained 107 Iraqi juveniles in the year after the invasion, holding most at Abu Ghraib prison.49 The U.S. military considered these children “high risk” security threats, stating that it had captured them while “actively engaged in activities against U.S. forces.”50

Sudan has seen the largest use of child soldiers in the region, with estimates reaching as high as 100,000 children who have served on both sides of the two decades–old civil war. Since 1995 the Islamic government in the north has conscripted boys as young as twelve into the army and the paramilitary Popular Defense Forces. Homeless and street children have been a particular target. Poor and refugee children who work or live on the streets have been rounded up into special closed camps. Ostensibly orphanages, these camps instead have often acted as reservoirs for army conscripts.51 The government has also targeted children in the towns it holds in the south to use against their kinsmen in the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Disturbingly, one report found that 22 percent of the total primary school population in Wahda province had been recruited into the Sudanese army or pro-government militias, the youngest being nine years old.52

The SPLA rebel group, in turn, has relied greatly on child fighters in its battle with the government. While it recently made a public relations gambit in demobilizing three thousand child soldiers, another seven thousand of its fighters (roughly 30 percent of its forces) are thought to be underage.53 Actually, the SPLA began a practice of “warehousing” young recruits in the mid-1980s. It would encourage and organize young boys to flee to refugee camps located beside its bases on the Ethiopian border. At the boys-only camps, those past the age of twelve would be given full-time military courses, while those younger were trained during school breaks. These boys became the basis of what was known as the Red Army, and were even subcontracted out to the Ethiopian army while it was still allied with the SPLA.54 Many of these boys later became the core of the famous Lost Boys of Sudan. When the Ethiopian regime allied with the SPLA fell in 1991, the refugees had to flee the camps on the Sudan-Ethiopian border. Thousands of boys had been separated from their families but were not yet incorporated into the SPLA. For the next decade, the unaccompanied boys wandered from refugee camp to refugee camp. Eventually, those who were unable to be reunified with their families were resettled in the United States in 2001.55

Child soldiers are also present in a number of areas in the region where American forces were deployed in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. Indeed, it was in Afghanistan that a fourteen-year-old sniper killed the first U.S. combat casualty in the war on terrorism. On January 4, 2002, Special Forces Sergeant 1st Class Nathan Chapman was on a mission in Paktia province to coordinate with local fighters. As he stood in the flatbed of a truck directing his unit, he was shot without warning from several hundred feet away. Just a few months later, another Special Forces trooper, Sergeant 1st Class Christopher Speer, was killed by a fifteen-year-old al Qaeda member while operating in Khost province. The young boy, who was originally from Canada, was the sole survivor of a group of al Qaeda fighters that had ambushed a combined U.S.-Afghan force. This led to a five-hour firefight involving massive air strikes. When U.S. forces went to sift through the rubble, the young boy popped up, with pistol in hand, and threw a grenade which seriously wounded Speer. The young boy was shot down by Speer’s comrades but survived his wounds. A few months later, he spent his sixteenth birthday at the U.S. detention facility at Guantánamo Bay. Three other juvenile detainees were already on-site: two were captured in raids on Taliban camps and one while trying to obtain weapons to fight American forces. By this time, however, Speer had died from his wounds. In a sad irony, Speer had risked his life just two days earlier by going into a minefield to save two injured Afghan children.56

The presence of child soldiers in the fighting in Afghanistan should not have been a surprise. Indeed, surveys have found that roughly 30 percent of all Afghan children have participated in military activities at some point in their childhood.57 When the Taliban became a force in the Afghan civil war in 1994, they gained strength and numbers by recruiting among young refugees who were attending Pakistani madrassahs (Islamic schools).58 As one Taliban fighter justified the practice, “Children are innocent, so they are the best tools against dark forces.”59

I regret that I fought and hate the war. It took everything from us. I have studied [until] sixth class. If there was not war, I would have already finished school by now.

—R., age eighteen60

Once in power, the Taliban’s leader, Mullah Omar, declared that any followers who were too young to grow a beard (a definition of maturity in line with the Taliban’s pre-Koranic doctrines) should leave the fighting. This decree was widely ignored, with many believing it was just for international consumption. For the last few years of the Afghan civil war, Taliban recruitment of children tended to be cyclical, coinciding with school holidays and major offensives or defeats. As a prelude to large-scale operations, the Taliban typically would truck in more than five thousand children from sympathetic madrassahs across the border in Pakistan. Many were under fourteen. These “temporary” child soldiers would then return to school after one or two months of fighting experience. The Taliban’s main foe, the Northern Alliance, also used child soldiers in the fighting in Panjshir valley, but was not as reliant on them.61 As late as 2003 some eight thousand child soldiers were thought to be still active in Afghanistan, participating in the fighting between the Afghan government, various warlords, and remnants of the Taliban and al Qaeda.62 U.S. soldiers continue to report facing child soldiers in Afghanistan, with the youngest on the public record being a twelve-year-old boy. He was captured in 2004 after being wounded during a Taliban ambush of a convoy.63

The practice of child soldiers is also highly prevalent in Asia. Children are engaged in insurgencies under way in Cambodia, East Timor, India, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and the Solomon Islands. In India, some seventeen different rebel groups are suspected of using child soldiers, including along the volatile Kashmiri border with Pakistan.64

We prefer to recruit children at the age of eleven or twelve.

—SYED SALAHUDDIN, supreme commander of Hizbul

Mujahideen (Kashmir-based militant group)65

Children have particularly been at the center of the explosion of rebel groups and internecine fighting on the many islands of Indonesia, such as in Ambon.66 There, thousands of Muslim and Christian boys have formed local paramilitary units that protect and raid against the other community. As one local aid worker notes, “They [the boys] are so proud of their contribution. It’s a common thing for them to say they’ve killed. Since the government can’t seem to do anything, they all say they have an obligation to protect their families and their religion.”67

It is estimated that Myanmar alone has more than 75,000 child soldiers, one of the highest numbers of any country in the world, serving both within the state army and the ethnic armed groups pitted against the regime. The army pulls in young children through its Ye Nyunt (Brave Sprouts) camps. As many as 45 percent of its total recruits are under age eighteen. Twenty percent are under fifteen, with some as young as eleven. The various rebel groups are estimated to have another six thousand to eight thousand child soldiers.68

The spillover effects of this recruitment of children were tragically illustrated in January 2000. When the Karen National Liberation Army rebel group began to collapse in the late 1990s, it broke up into a number of new groups. One of these, the Christian Karen militia “God’s Army,” was led by twelve-year-old twin brothers, the enigmatic Luther and Johnny Htoo.

The group gained notoriety not only from the famous picture of the two young leaders smoking cigars, but also when young members of their group took hundreds of hostages at the Ratchaburi hospital in Thailand. The fighters were subsequently killed in a commando attack broadcast live on Thai TV, and the group’s camps were overrun. Ultimately, Luther and Johnny were reunited with their mother in a Thai refugee camp. The family has since applied for asylum in the United States, and their whereabouts are no longer publicly known.

The Philippines is another nation where U.S. forces have deployed as part of the war on terrorism. Likewise, it has an array of rebel groups using child soldiers. The communist New People’s Army (NPA) is thought to have around a thousand child soldiers, mostly in the age range of thirteen to seventeen.69 The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), a Muslim rebel group, has recruited children from elementary schools as young as nine. Abu Sayyaf, a radical breakaway group from the MILF, is suspected of being linked to al Qaeda (Osama bin Laden’s brother-in-law was a financier for the group). In turn, it is also known to have boy soldiers whose ages range from eleven to fifteen. Some are volunteers, while others were actually sold to the group by their parents.70 These dynamics of multiple rebel groups with child soldiers have presented a terrible dilemma for Filipino military forces, who are now fighting the groups alongside U.S. military advisors. As one Filipino marine sergeant stated, “How does one know if the enemies are children? They have guns like us, they are in full uniform and they fight like any other soldier. But if you mean have I seen young dead enemies, most of the dead I saw were young.”71

These examples provide only highlights of the extent of the spread of child soldiers, not its entirety. They demonstrate just how deeply involved children have become in contemporary warfare. The manner in which many groups go about creating military capability has changed. Moreover, child soldiers are a new feature of nearly every area at war in our world. When analysts write of the “pre-modern” zones of “anarchy,” “chaos,” and “turmoil” (to use some of the most common terms) that characterize the emerging geopolitical structure, they are talking of the areas where children now carry out warfare.72

While these examples speak volumes, the raw numbers are also telling. Of ongoing or recently ended conflicts, 68 percent (37 of the 55) have children under eighteen serving as combatants.73 Eighty percent of these conflicts where children are present include fighters under the age of fifteen.

In turn, this means that children are increasingly present in the various armed organizations that cover the globe (that is, both state militaries and all armed non-state groups operating in a politico-military context). Indeed, more than 40 percent of the total armed organizations around the world use child soldiers (157 of 366).

It is important to note that these are not just children on the borderline of adulthood, but include those considered underage by any cultural standard. Twenty-three percent of the armed organizations in the world (84 total) use children age fifteen and under in combat roles. Eighteen percent of the total (64) use children twelve and under.74 While the exact average age of the entire set of child soldiers around the world is not known, it appears to be well below the eighteen years threshold. In one survey taken of child soldiers in Asia, the average age of recruitment was thirteen. However, as many as 34 percent were taken in under the age of twelve.75 In a separate study in Africa, 60 percent were fourteen and under.76 Another study in Uganda found the average age to be 12.9.77 Indeed, many child soldiers are recruited so young that they do not even know how old they are. As one boy from Sierra Leone thought to have been seven or eight when he was taken tells, “We just fought. We didn’t know our age.”78

Seven weeks after I arrived there was combat. I was very scared. It was an attack on the paramilitaries. We killed about seven of them. They killed one of us. We had to drink their blood to conquer our fear. Only the scared ones had to do it. I was the most scared of all, because I was the newest and the youngest.

—A., age twelve79

The generally accepted estimate is that well over 300,000 children are currently fighting in wars or have recently been demobilized.80 However, this figure is from a series of country case studies (twenty-six in all) and thus may be at the low end of the likely total, given the number of conflicts that were not included in the studies. To some, 300,000 is an immense number, while others might note that relative to the overall number of armed personnel in the world, it is a small percentage. However, when looking at the armed forces actually involved in conflict in the world at this time (as opposed to those at peace), it makes up just under 10 percent of all combatants.81 What is more significant is that this number was near zero just a few decades ago.

Any debate over the numbers, though, belies the real issue at hand, the vast changes in war and breakdown in norms that these figures signify. Graça Machel, the former first lady of Mozambique and wife of Nelson Mandela, has served as a special expert for the United Nations on the topic. She perhaps said it best:

These statistics are shocking enough, but more chilling is the conclusion to be drawn from them: more and more of the world is being sucked into a desolate moral vacuum. This is a space devoid of the most basic human values; a space in which children are slaughtered, raped, and maimed; a space in which children are exploited as soldiers; a space in which children are starved and exposed to extreme brutality. Such unregulated terror and violence speak of deliberate victimization. There are few further depths to which humanity can sink.82

Non-state actors such as armed rebel, ethnic, and political opposition groups are especially likely to use children as fighters. Sixty percent of the non-state armed forces in the world (77 of 129) use child soldiers. But children’s use as soldiers is by no means limited to non-state actors or to armies actively at war. The United Nations estimates that, in addition to the 300,000 active child combatants, more than fifty states actively recruit at least another half million children into their military and paramilitary forces, in violation of both international law and usually their own domestic laws.83

An army recruitment unit arrived at my village and demanded two new recruits. Those who could not pay 3000 kyat [$400] had to join the army.

—Z., age fifteen84

In many countries, the children are incorporated through schools and armed youth movements, in which military training and indoctrination occur. These groups then form a valued reserve for the local regime to use to its own ends, particularly during a wartime manpower crunch.

Typically, states have larger and more formalized military apparatus able to incorporate more recruits. So, states’ use of children often occurs in quite high numbers. For example, of the approximately 60,000 personnel in the El Salvadoran military during its civil war, ex-soldiers estimated that about 48,000 (80 percent) were less than eighteen years of age. Colombia’s national security forces once included more than 15,000 children.85

Subject to the same military law as adults, children serving in state forces are often no better off than their compatriots across the lines. In Paraguay, for example, children as young as twelve are illegally recruited into the military. Many are then particularly targeted for ill treatment and punishment, which has resulted in several deaths of underage recruits.86 Other case studies in Colombia, Ethiopia, Liberia, and Uganda all similarly report children being beaten or even shot for trying to escape government recruitment, or for disobedience or desertion (the use of the death penalty against children, though, is in contravention of international law; the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights prohibits capital punishment for persons less than eighteen years old).87 In Russia, a number of army regiments have admitted boy orphans between the ages of twelve and seventeen who have nowhere else to go. In the words of one regimental commander, despite their youth, the boys can expect to be treated as regular soldiers. “Here they learn to be manly. No one licks them clean and no one pities them. Regardless of their age, they’re treated as grown-up men, not as boys of their mental and psychological level of development.”88

Another new wrinkle in the child soldier phenomenon is that the problem crosses gender boundaries. In the isolated instances in the past when children were used on the battlefield, they were exclusively boys. Now, while the majority of child soldiers are still male, there are significant numbers of girl fighters under the age of eighteen. Roughly 30 percent of the world’s armed forces that employ child soldiers include girl soldiers. Underage girls have been present in the armed forces in fifty-five countries. In twenty-seven of these, girls were abducted to serve and in thirty-four they saw combat.89

Their numbers in these wars are equally significant. In the 1990s civil war in Ethiopia, as much as 25 percent of the total opposition forces were females under eighteen years; in turn, about 10 percent of the child soldiers in the PKK in Turkey are girls.90 Similar percentages of female child soldiers (in the 10 to 25 percent range) also hold for the Shining Path in Peru, the FARC in Colombia, the LRA in Uganda, and in the fighting in Manipur, India. The LURD rebel group in Liberia (which later became part of the ruling government after it won the war) even organized a Women’s Auxiliary Corps made up of young girls.91

I had a friend Juanita, who got into trouble.… We had been friends in civilian life and we shared a tent together. The commander said that it didn’t matter that she was my friend. She had committed an error and had to be killed. I closed my eyes and fired the gun, but I didn’t hit her. So I shot again. The grave was right nearby. I had to bury her and put dirt on top of her. The commander said, “You did very well. Even though you started to cry, you did well. You’ll have to do this again many more times, and you’ll have to learn not to cry.”

—A., age seventeen92

The most significant user of girl soldiers, though, is perhaps the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Fighting in Sri Lanka since the mid-1980s, the group systematically recruits children. It has even gone so far as to establish the LTTE Bakuts, a unit known as the “Baby Brigade” made up of fighters sixteen and under. Estimates indicate that between 40 and 60 percent of its fighting forces are recruited below the age of eighteen, mostly in the ten to sixteen-year-old range. Roughly half of these LTTE troops are female, called “Birds of Freedom” by their fellow rebels. Many of these children have received specialized training as suicide bombers. The LTTE makes the startling claim that recruiting Tamil girls is its way of assisting women’s liberation and counteracting the oppressive traditionalism of the present system.93

To the north, the Maoist Lal Sena insurgency in Nepal has similarly been proud of its recruitment and employment of girl fighters. Since the group’s emergence in 1996, more than five thousand Nepalese have died in the fighting, three hundred of them children; starting in 2002, the United States became involved in this conflict by giving the government tens of millions in military aid.) Lal Sena has recruited some four thousand child soldiers between the ages of fourteen and eighteen (around 30 to 40 percent of its total forces.94 Its own propaganda highlights the fact that girls represent great numbers of this total and even describes the military activity of girls as “another bonanza for the revolutionary cause. That is, the drawing of children into the process of war and their politicisation.”95 Lal Sena is interesting in that it began to employ young girl and boy fighters after training and consultation with other rebel/terrorist organizations, including the Shining Path in Peru and Indian militant groups.96 This indicates that there are teaching pathways by which the child soldier doctrine has been spread.

The fact that sexual abuse is often a common part of the child soldiering experience for these girls debunks any idea that their recruitment is somehow progressive. While they may be expected to perform the same dangerous functions as boy soldiers, many are also forced to provide sexual services or become “soldiers’ wives.” For example, the LRA in Uganda, a self-proclaimed “Christian” resistance group, specifically targets girls considered more attractive for abduction. They are then “married” to the organization’s leaders as spoils of war. If the man dies, the girl is then given to another rebel. In Angola, girl soldiers were labeled by the rebel group as Okulumbuissa, a lower social category which sanctions a man to impregnate the girl without having to assume paternity and responsibility for the child.97

They picked me and took me away in the bush where I was forced to become a “wife” to one of the rebels. Being new in the field, on the first night I refused, but on the second night, they said, “Either you give in or death.” I still tried to refuse, and then the man got serious and knifed me on the head. I became helpless and started bleeding terribly and that was how I got involved in sex at the age of 14 because death was near.

—B., age sixteen98

Many of these girls then become pregnant. What happens next usually depends on the group’s decision rather than the young mother’s choice. For example, when a girl in the FARC in Colombia becomes pregnant, she often is forced either to have an abortion or give her baby to local peasants. When the child reaches thirteen, he or she is reclaimed by the FARC as part of the next generation of recruits.99 In contrast, women in the LRA tend to keep their children. But in doing so, they become more wedded to the group, because their escape options are further limited. Observers thus report seeing young LRA girls in the midst of combat, fighting with babies strapped to their backs. These widespread abuses inevitably complicate attempts by former girl soldiers to reintegrate into their communities and families.100