I was attending primary school. The rebels came and attacked us. They killed my mother and father in front of my eyes. I was 10 years old. They took me with them … They trained us to fight. The first time I killed someone, I got so sick, I thought I was going to die. But I got better … My fighting name was Blood Never Dry.

—D., age sixteen1

The act of joining an armed group is only the first step in a child’s path to war. Becoming a child soldier is a longer process, involving indoctrination, training, and then battle.

Indoctrination is the act of imbuing a child with the new worldview of a soldier. Traditionally, this opening step is key in the process for turning any civilian into a soldier. It provides what analysts call “sustaining motivation,” the collection of factors that keep soldiers in the army despite the risks and rigors of the campaign. It also provides the “combat motivation,” the factors that keep soldiers on the field in the heat of battle.2 Children are obviously not the prototypical recruit, so their indoctrination is a critical determinant to the overall success of any putative child soldier doctrine.

Historically, armies have had three general types of motivators to offer their soldiers: coercive motivators, based on physical punishment; remunerative motivators, based on the promise of material rewards; and normative motivators, based on the offer or withdrawal of such psychological rewards as honors and group acceptance.3 Each of these is intended to keep the soldier in the army and lead him to take risks and commit acts of violence that he would likely not do otherwise.

Coercive motivation has been the most commonly applied technique for professional armies across history. For example, Frederick the Great believed that a soldier must be “more afraid of his officers than of the dangers to which he is exposed.”4 Similarly, British armies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries made frequent use of the lash to discipline soldiers for desertion, straggling, and cowardice; sentences of a hundred to two hundred lashes were not uncommon.5 Other common practices were to force a soldier to “run the gauntlet” (be beaten by a line of his messmates) or march with a cannonball chained to one ankle if he failed to follow orders without question. On occasion, soldiers were punished by death.6

This primary use of force in the initial act of indoctrination is equally characteristic of child soldiers. Few of the forces they join deign to offer children true remunerative rewards, while normative motivators require allegiances and relationships that build up only over time. This is often contrary to most conflict groups’ motivation to use the children on the battlefield as rapidly as possible.

Therefore, whether they have joined a state military or a rebel group, the entire process of their indoctrination and then training typically uses fear, brutality, and psychological manipulation to achieve high levels of obedience. For example, in many state armies, children generally receive much the same treatment as adult recruits. When the target is a child, these often brutal training-induction ceremonies, which may involve beatings and humiliation, become acts of sadism. A typical case is in Paraguay, where government military trainers beat children as young as twelve with sticks or rifle butts and burn them with cigarettes, all with the intent of trying to turn them into soldiers. Those who resist or who attempt to escape are further beaten or even killed.7 More than 111 underage conscripts have died in the Paraguayan army since 1989.8

Once children are locked within a military organization that has chosen to utilize child soldiers, thus already violating the law and common codes of morality, few constraints exist on what trainers might choose to do. In turn, child soldiers become quickly dependent on their leaders for their protection from capricious violence as well as their every need. Combined with liberal amounts of terror and propaganda, impressionable children can rapidly begin to identify with causes they barely understand.

The exact types of indoctrination vary by group, but all take place at a time at which the child is at his weakest emotionally and psychologically—disconnected from family, traumatized, and at a fundamental loss of control. The overall intent of the process is to create a sort of “moral disengagement” from the violence that children are supposed to carry out as soldiers.9

Typically, groups not only utilize threats of punishment against the children but also seek to diffuse any sense of responsibility among the children for future violence. These may include dehumanizing their victims, such as by creating a “moral split” that divides the world into an “us versus them” dichotomy. For example, young recruits in the LTTE are continually taught that those outside the cause are enemies and should be killed. They are also shown videos of dead women and children. This inures them to violence as well as creates a sense of righteousness in targeting outsiders, as the children are told that the group’s enemies did it. The effect is that many children often emerge from such programs with weakened senses of remorse and obsessions with violence.10

Another indoctrination tactic is to attempt to realign the child’s allegiances and worldview. This involves both traditional modes of propaganda and what many would term “brainwashing.” Young members of the RUF, for example, were encouraged to call their leader, Foday Sankoh, “Pappy.” Part of their indoctrination program was to declare that he was now their father. Sankoh was also compared in the program to Jesus and the Prophet Mohammed. Similarly, all LTTE recruits swear an oath of allegiance to the group’s leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran, every morning and evening, and he is similarly described as a father figure.

Many groups also utilize the creation of alternative personas to neutralize the effect of the antisocial actions they are attempting to indoctrinate.11 Across regions, child soldiers typically take on nicknames. Some of the names are simply juvenile, such as “Lieutenant Dirty Bathe” (because he never took a bath), while others are chilling, such as “Blood Never Dry.” The renaming, sometimes called locally “jungle names,” is termed “doubling” by psychologists.12 The renaming not only seeks to dissociate the children from culpability for the violence and crimes they commit, but also is intended to indicate a complete split with their prior self. Some units of child soldiers in Sierra Leone even took to calling themselves “cyborgs,” self-consciously denoting themselves as human killing machines with no feelings.13

It’s like magic. I killed people and it doesn’t stick to me. I still go to heaven.

—“Bad Pay Bad,” age unknown14

There is also often a physical aspect of reidentification in the indoctrination process. Many groups, such as the LTTE, shave their children’s heads (akin to joining a professional military). This not only inculcates a break in identity, but also makes escapees easier to identify.15 Some organizations even go to the extent of branding their new child recruits with the group’s name or insignia. Leaders of the Revolutionary United Front in Sierra Leone, for example, would carve “RUF” onto children’s chest, arms, and even foreheads with anything from needles to broken glass. In doing so, the scarring became not only a part of indoctrination but also acted as a lifelong stigma intended to keep children from returning to communities where the RUF was hated. As one former child soldier sadly describes, “I was branded because they said I would run away and now I can’t even run away from my own self. Evil is with me all the time, imprinted on my body.”16

I was on my way to the market when a rebel demanded I come with him. The commander said to move ahead with him. My grandmother argued with him. He shot her twice. I said he should kill me, too. They tied my elbows behind my back. At the base, they locked me in the toilet for two days. When they let me out, they carved the letters RUF across my chest. They tied me so I wouldn’t rub it until it was healed.

—A., age sixteen17

The ultimate method of indoctrination, though, goes beyond these crimes. A popular tactic among the groups most dependent on child soldiers is to force captured children to take part in the ritualized killing of others very soon after their abduction. The victims may be POWs from the other side, other children who were abducted for the sole purpose of being killed in front of the recruits, or, most heinous of all, the children’s own neighbors or even parents. The killings are often carried out in a public manner, such that the home community knows that the child has killed, with the intent of closing off any return.18

In some countries, including Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Peru, and Mozambique, child soldiers have been forced to perform ritualistic acts of cannibalism on their victims, such as eating the victim’s heart.19 This is also calculated to instill contempt for human life. Any recruits who balk risk becoming the victims themselves, forcing the most terrible of choices upon a child.

I don’t want to go back to my village because I burnt all the houses there. I don’t know what the people would do, but they’d harm me. I don’t think I’ll ever be accepted in my village.

—I., age sixteen20

Former child soldiers typically cite this as the defining moment that changed their lives forever. Designed to break down resistance to the group’s authority and destroy taboos about killing, the effect of the killing is to not only terrorize the children, but also implicate them in the worst acts of violence. Having crossed the ultimate moral boundary, they are made anathema to the only environment they knew and thus are even more reliant on their new organization. Their only two anchors in life become their guns and their fellow fighters. After this, their compliance to orders will often be near total. As Corinne Dufka of Human Rights Watch describes the practice, “It seemed to be a very organised strategy of … breaking down their defences and memory, and turning them into fighting machines that didn’t have a sense of empathy and feeling for the civilian population.”21

It’s easier the second time. You become indifferent.

—L., age fifteen22

Whatever the means, the typical result of the indoctrination process is a moral and psychological disconnection that allows children to engage in what would normally be considered depraved actions. The effectiveness of these programs is heightened by the fact that many of the children who grow up in a climate of war may already lack the internal constraints against violence that ordinarily develop. Many will never have had exposure to positive role models, a healthy family life, the rewards for socially constructive behaviors, and the encouragement of moral reasoning. However, the effect is not limited to those of any particular background. These indoctrination techniques even have their parallel in all sorts of initiation processes across cultures (from street gangs to fraternities). As one psychologist notes of his time spent trying to rehabilitate child soldiers, “It was sobering to think that under certain conditions, practically any child could be changed into a killer.”23

The typical process of turning a civilian into a soldier involves recruitment, indoctrination, and then training in basic and later specialized military skills. However, some children were recruited to fill out such support roles as cooks, porters, or unarmed sentries. Thus, these kids are given little to no skills instruction, but set right to work. Children can also play certain uniquely valuable roles in guerrilla warfare. Local officers frequently note how children can move about more freely than adults, and are not instantly suspected of spying or supplying.24 These secondary functions still entail great risk and hardship, though.

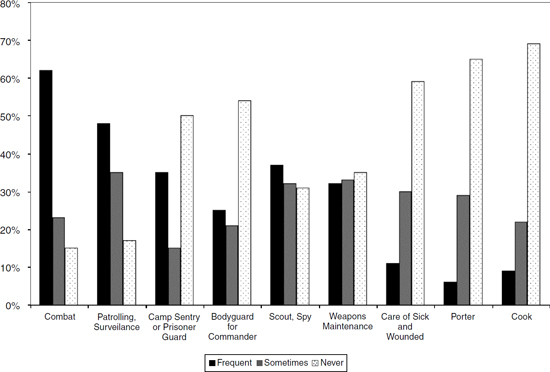

SAMPLE CHILD SOLDIER TASKS AND DUTIES

Source: International Labour Office, “Democratic Republic of the Congo Survey,” in Wounded Childhood: The Use of Children in Armed Conflict in Central Africa (Geneva, 2003), p. 39.

I worked as a spy. They gave me cigarettes, groundnuts and other things to sell. While I was selling, I’d get information. I’d find out where the rebels had stored their weapons, what type of weapons they had, and where their base was located so we could attack them. If the base was not too far away, I’d just spend the day and go back to our base. If it was far away, I’d have to stay for a day or two before reporting back to my base. I was a good spy because all the information I gathered was used to launch attacks. Most times we were successful, so I think I was a good spy.

—I., age twelve 25

In the end, though, the majority of children are primarily recruited to fight, and most are quickly trained to this task. Thus, while it is often claimed that child soldiers rarely fight, research indicates that the majority of child soldiers do participate in combat. In one global survey 91 percent of child soldiers had served in combat.26 Another survey carried out in Colombia among FARC, ELN, and AUC child soldiers found that 75 percent had been in combat at least once, with multiple interviewees taking part in more than ten battles.27 A third survey in Africa found that 87 percent had served on the front lines.28 In Liberia, approximately 80 percent of the child soldiers were involved in direct combat.29

The typical training pattern is that the children are given short instruction in the most basic infantry skills: how to fire and clean their weapons, lay land mines, set an ambush, etc. There are also frequent attempts at instilling some form of basic discipline and esprit de corps, such as forced marches and parades. Training can range from a day to up to eleven months (the longest being in the RCD–Goma conflict group in the DRC). The training might either take place all at the start or, in some cases, with a period of brief training, then deployment and return for more advanced training after gaining combat experience. This variance is usually situationally dependent. For example, LRA members were run through formalized and much longer training programs before 2002, while the group had safe base camps in Sudan. Once the group was forced on the run by the Ugandan army, the training became far more sporadic. In either case, training levels are generally well short of the common standards of Western professional armies in both skills and duration, but are usually enough to learn how to kill effectively.

States’ training of child soldiers is typically highly institutionalized, consisting of running them through formal training programs that mimic those given to adults. Children in state units are also often supplied with uniforms, regular rations, and even pay.

One example of the state-structured approach toward child soldiering was that of Iraq under the rule of Saddam Hussein. Over the past decade, the regime laid the groundwork for child soldiers by running a broad program of recruitment and training. Since the mid-1990s there were yearly military-style summer “boot camps” organized by the regime for thousands of Iraqi boys. During these three-week sessions, boys as young as ten were run through drills, taught the use of small arms, and provided with heavy doses of Ba’athist political indoctrination. The military training camps were often named after resonating current events, to galvanize recruitment and bolster political support (for example, the 2001 summer camp series was named for the “Al Aqsa Intifada”). In addition, starting in 1998, there were a series of training and military preparedness programs directed at the entire Iraqi population. Youths as young as fifteen were included. The preparedness sessions, which generally ran for two hours a day over forty days, mandated drilling and training on small arms.

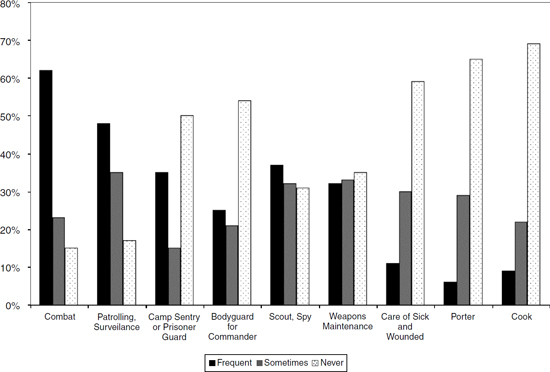

SAMPLE TRAINING PROGRAMS FOR CHILD SOLDIERS

Source: International Labour Office, “Democratic Republic of the Congo Survey,” in Wounded Childhood: The Use of Children in Armed Conflict in Central Africa (Geneva, 2003), p. 39.

The Iraqi regime also worked to train specialized child soldier units, most notably the Ashbal Saddam (Saddam’s Lion Cubs). This organization was formed after Iraq’s defeat in the 1991 Gulf War, when the regime’s hold on power faltered. The Ashbal Saddam involved boys between the ages of ten and fifteen who attended military training camps and learned the use of small arms and infantry tactics. The camps involved as much as fourteen hours per day of military training and political indoctrination. They employed training techniques intended to desensitize the youth to violence, including frequent beatings and deliberate cruelty to animals (the recruit might be asked to strangle a chicken or shoot a dog).

Rebel groups’ training of child soldiers is typically less institutionalized and tends to be shorter. Their instructors may even be other child soldier “veterans.” Of rebel groups, the Tamil Tigers may have the most developed child soldier training program, mimicking many of the drill techniques used by professional militaries. Developed in the early 1990s by the LTTE’s military leader Wedi Dinesh, it was designed to make the LTTE’s child soldiers more capable and daring than its adult fighters had been.30 All links between the children and their families are broken, and the children are trained for four months in the jungle. Sleep and food are carefully regulated to establish control and build endurance. Each day the children wake at 5 a.m. and are put through physical training for two hours. They then spend the rest of the morning learning the use of their weapons, small unit tactics, parade drill, and other specialized skills such as rope climbing, codes, and map reading. The afternoon is divided between political indoctrination, including the reading and memorization of LTTE party literature, and more physical and skills training. During the evenings adult LTTE leaders deliver lectures. The topics vary—communication, explosives, and intelligence techniques—covering the child soldier equivalents to professional development programs. In all areas, risk-taking is highly extolled, including even screening movies that show a daredevil approach to battle prevailing.

This pattern holds for the other child soldier groups. Indeed, one of the few noticeable differences between the LTTE’s training program and that of the FARC in Colombia is that FARC child soldier trainees typically begin their day at 4:30 a.m. rather than 5 a.m.31

Harsh discipline and the threat of death continue to underscore the training programs of almost all child soldier groups. In the LRA, for example, recruits’ physical fitness is assessed and then built up by having them run around the camp’s perimeters while carrying stones on their shoulders. Those who spill the stones or collapse are killed.32 Those who disobey during marksmanship training risk having their fingers cut off.33 In LTTE training classes, the first child to voice an interest in going home is beaten in front of the other children, effectively deterring others. Quitting during training activities is punished by sentences of harsh labor, including breaking stones or digging bunkers.34 In the FARC and ELN, minor transgressions, such as consuming alcohol without permission, are punished by tying the child by their hands and neck to a pole for five days.35 State armies are often equally harsh. In the Myanmar army, boys who arrive late for their tasks or refuse to eat their food are beaten by the other recruits with bamboo sticks. In some cases, officers literally rub salt in their wounds.36

Once minimally trained, most new recruits are set very quickly out on the battlefield; to not use them as soon as possible goes against the very rationale for their recruitment. Moreover, their participation in operations can bind them tighter to the organization. At the same time, new child soldiers can be used to seize more children and build the group’s numbers.

Despite their negligible training, the often cruel indoctrination and training programs mean that young children can be turned into the fiercest of fighters. Weakened psychologically and fearful of their commanders, children can become obedient killers, willing to carry out the most dangerous and horrifying assignments. When they do take on other armed forces rather than civilians, young children rarely fully appreciate the dangers of the battlefield. The result is that in the midst of combat they often get overly excited and take undue risks, sometimes even failing to take cover. Or, as one rebel commander in the DRC commented, “Children make good fighters because they are young.… They think it’s a game, so they’re fearless.”37

Many believe that this fearlessness derives directly from the very state of childhood—that is, children are simply not as capable of understanding the consequences of their actions as adults. There are both psychological and physical explanations for this difference. Children, most particularly those in the pre-adolescent years, tend to have what is known as an “underdeveloped death concept.” Children’s psyches often have not yet developed a sense of their own mortality (death is a meaningless concept). Thus, children are generally psychologically incapable of weighing all the possible consequences of their actions in realistic terms.38

Researchers are beginning to believe that there may be an underlying physical basis for this difference. The prefrontal lobe is the part of the brain that some scientists speculate plays a crucial role in inhibiting inappropriate behavior. It does not reach its full development until as late as the age of twenty.39 This provides an explanation for why children do not simply act like little adults, as well as further reasons as to why children are not morally equivalent actors in the realm of war.

I don’t know why I killed these people. I killed them at a distance and at close range. I killed many. We didn’t kill civilians if we were attacking a village and there were no enemies. The people we sent on reconnaissance would tell us who the enemy was. If there were enemies, we’d kill civilians. We had to kill our brothers too. If one of us committed a crime, our commander would tell us to beat him to death. One time, I had to beat and kill one of the other rebels. During an ambush, he’d fired when he wasn’t supposed to, and we were discovered. I started beating him, but I didn’t have the strength. So an older rebel beat him to death.

—I., age twelve 40

A number of groups also try to reinforce this natural fearlessness by having the children take drugs or alcohol. The type of drug tends to depend on availability. The most common are cocaine, barbiturates, and amphetamines. Local concoctions are also highly favored. In Liberia and Sierra Leone, for example, a favorite was “brown-brown,” cocaine or heroin mixed with gunpowder to make it stronger, while khat, a strong stimulant, is favored in East Africa. Initially, the child soldiers tend to be forced to take these drugs. Where needles were not available, group leaders make incisions around the child’s temple and arm veins, pack the drugs in, and then cover the wound with plaster or a bandage. RUF child soldiers report that if they refused (called “technical sabotage” by rebel commanders), they would be killed.41

We smoked jambaa [marijuana] all the time. They told us it would ward off disease in the bush. Before a battle, they would make a shallow cut here [on the temple, beside his right eye] and put powder in, and cover it with a plaster. Afterward I did not see anything having any value. I didn’t see any human being having any value. I felt light.

—A., age fifteen42

Later, as addiction grows, most begin to take the drugs voluntarily. By the end of the war in Sierra Leone, for example, social workers estimated that more than 80 percent of the RUF’s fighters had used either heroin or cocaine.43

The outcome of this drug usage is that children become even more inured to violence and its consequences, almost operating on another plane of reality. In the words of the director of a child soldier repatriation camp, children “would do just about anything that was ordered” when on drugs.44 As one boy soldier described the feeling, “I became stronger … They gave me a weapon and put some marks on my face. I was no longer human. I could do anything.”45 Another twelve-year-old noted how with drugs he was never afraid of going into battle: “After the injection, you just feel like doing any bad thing. You become a wounded man.”46 Canada’s Lieutenant General Roméo Dallaire witnessed the effects while commanding the UN forces during the Rwandan genocide. He has an even more frank description: “Their brains are fried. On drugs, they will do anything.”47

Regardless of what causes it, though, this tendency toward fearlessness is deliberately exploited by many child soldier organizations. Although some commanders have complained that child soldiers take excessive risks and can slow operations down through “misbehavior,” many others actually prefer leading child soldiers to adults, because of this risk-taking and rote obedience.

My missions included diamond mining near Kono [Sierra Leone], drug purchasing, collecting ammunition in Liberia, looting villages and capturing civilians. I used to buy drugs at the Liberian border from a man called Papi. They forced us to take them. This is where they would cut and put the “brown-brown.” [He shows a raised welt on his left pectoral.] We would then inhale cocaine. During operations, I sometimes would take it two or three times a day. I felt strong and powerful. I felt no fear. When I was demobilized I felt weak and cold and had no appetite for three weeks.

—Z., age fourteen48

Child soldiers are willing to follow the most dangerous of orders without question. As one commander in Myanmar noted of his troops, “Child soldiers are always very eager to go to the front lines.”49 A former child soldier in what was the RENAMO resistance group in Mozambique explained that his group grew to “not use many adults to fight because they are not good fighters … kids have more stamina, are better at surviving in the bush, do not complain and follow directions.”50 Half the globe away, a Khmer Rouge commander in Cambodia similarly commented, “It takes a little time, but eventually the younger ones become the most effective soldiers of them all.”51

The general result is that, despite their smaller physical size and development, child soldiers are serious players on the modern battlefield. As one report describes:

Children make very effective combatants. They don’t ask a lot of questions. They follow instructions, and they often don’t understand and aren’t able to evaluate the risks of going to war. Victims and witnesses often said they feared the children more than the adults because the child combatants had not developed an understanding of the value of life. They would do anything. They knew no fear. Especially when they were pumped up on drugs. They saw it as fun to go into battle.52

For rebel groups, the standard unit tactic is to place child recruits in small platoon-sized groups (roughly thirty to forty children) under the command of a few adults. The children are most often grouped by age. Units tend to stay on the move and operate as raiding parties. As they are usually targeting civilians or ambushing much smaller opposition units or outposts, their effect can be devastating.

The use of child soldiers by state militaries is dependent on the context that led to the adoption of the child soldier doctrine. Typically, when these forces are fighting against guerrilla groups, children are mixed in with standard units of adult soldiers to maintain some form of control. In conventional wars, where they have often been brought in as stopgap measures, they are set out on their own in the front lines to act as cannon fodder or disrupt advancing enemy formations.

Many groups often attempt to break in their new child soldiers by first using them to attack “soft” targets such as villages or weakly defended military or police posts. This both ensures success and inculcates the child into the machine of killing. It also adds a powerful psychological aspect to the operations. The groups make examples of recalcitrant villages or areas, killing or pillaging with little mercy. However, they generally release just enough survivors to spread the story. Thus, terror becomes one of the groups’ best weapons.

The first time we went out on patrol, we attacked a village and we killed so many people. I was afraid that first time. I don’t know how many people I killed, because I was just shooting. I couldn’t see anything. They just told me to shoot.

—L., age twelve53

I can never forget being in the battlefield for the first [time]. At first, I couldn’t pull the trigger. I was lying almost numb in ambush watching kids my age being shot at and killed. That sight of blood and crying of people in pain, triggered something inside me that I didn’t understand, but it made me past the point of compassion for others. I lost my sense of self.

—I., age fourteen54

However, child soldiers have also been proven to be quite effective even when facing regular adult troops. Their audacity, plus their sheer numbers and firepower, is sometimes able to make up for their relative lack of size, experience, and formal military training. It also helps that the adult troops of developing state armies are often even less trained than the child soldiers they face.

The tactics that are utilized then tend to vary by the situation and level of training. The use of human wave attacks by child soldier groups is quite common. The prevailing model is the brief use of preparatory fire, usually with mortars and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). This is quickly followed by a mass charge of the child soldiers, described by one Western soldier who witnessed the practice in West Africa as “yelling and screaming while blasting away on automatic. They generally overrun the objective with some ease, as the defenders are simply not much better.”55 An adult soldier in Myanmar recalled the terrifying experience of facing such a child soldier attack: “There were a lot of boys rushing into the field, screaming like banshees. It seemed like they were immortal, or impervious, or something, because we shot at them, but they just kept coming.”56

The LTTE may be the most effective at this type of attack. In the battles over the northern peninsula of Sri Lanka, it faced a series of highly fortified Sri Lankan army bases.57 It first deployed child soldiers against these in 1990, in an attack on the army camp at Mankulam. This attack was initiated by a suicide bomber driving a truck through the gate just before dawn, followed by a barrage of mortars, RPGs, and machine guns. Waves of LTTE fighters drawn from the Baby Brigade then followed and captured the fort by mid-afternoon.

Over the next decade the LTTE attacks gained in complexity and scale. By the mid-1990s the LTTE began to perfect its strategies, deploying a mix of Baby Brigade fighters with Black Tigers, which were specially trained suicide units. The LTTE provided the Baby Brigade units with new training in night combat, as well as boat handling and long-distance swimming to add an amphibious element. Reconnaissance and intelligence began to be emphasized and the forces even rehearsed on near-life-sized models of the attack objectives. The greatest victory came in 1996, when the LTTE launched Oyatha Alaikal (Operation Ceaseless Waves) on the Multavi military complex. Ultimately the attack involved more than five thousand LTTE troops and included both child soldier human wave attacks by land and amphibious assault troops and suicide bomb boats by sea.58 To sow confusion, a number of LTTE leaders also dressed in Sri Lankan army uniforms. In the end, the force overran the complex and beat back a relief force. Out of a total defending force of 1,242 soldiers, the attackers killed 1,173 (roughly 300 were killed after being captured). The LTTE suffered casualties of around 300 killed and 1,000 wounded.

The Multavi operation illustrates that, despite their usual grouping in smaller platoon-sized units, child soldier forces can operate strategically. Their organizations are able to coordinate them into battalion-level or even larger operations. These larger operations tend to occur when their foe has been intentionally overextended and made more vulnerable. A series of prefacing feints and smaller attacks may be used to prompt this, intended to cause the opposition force to disperse to protect its supply lines. The group then cuts the supply lines, masses its own small units, and focuses an attack designed to overwhelm certain isolated units. During peacekeeping or coalition operations, child soldier forces have also been surprisingly savvy in targeting the politically weakest contingents. For example, this was a particular strategy used against the ECOMOG in Liberia and Sierra Leone. The result was that several of these lesser national contingents were pulled out, increasing the burden on the core state units (in this case, Nigeria).

Child soldier organizations have also demonstrated an awareness of the unique problems they present by putting children on the battlefield (covered further in Chapter 9). They often try to take deliberate advantage of the moral and operational dilemmas that result.59 In a number of cases, including Colombia, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and the DRC, the youngest units (known as “small boy units”) are used as the spearhead of assaults. Often, the children are sent forward naked, to create further sympathy and confusion among their opponents. Naked children are also believed to be imbued with magical powers in certain tribal cultures, adding to the disruptive effect.

The cover of children’s assumed innocence is also often utilized to a force’s advantage. In Iraq, rebel groups reportedly used children both as scouts and spies, particularly when targeting U.S. convoys. In other reported situations, they would deliberately move in front of U.S. convoys at traffic junctions, as if they were playing, whereupon the convoy, now stopped, would be attacked by accompanying forces.60 In West Africa, seemingly unarmed children sometimes were left as “bait” in supposedly abandoned villages. Unsuspecting troops who went to their aid would then find themselves attacked by the children and a hidden force around them. Other common tactics included infiltration techniques, such as appearing to be playing games or attempting to trade with the opposing force as a cover for an ambush, as well as false surrenders.61

Over time, children gain combat skills and become shockingly proficient fighters—that is, if they survive their initial years of fighting. Those who know best often remark on the skills of these small but experienced soldiers. One retired Green Beret officer who worked with the child soldiers in the SPLA’s Fifteenth Brigade in a private capacity described them as “the best soldiers I’ve seen in Africa.” He estimated that roughly 50 percent of these were in the fourteen-year-old range and below. He also described the Colombian, Thai, and Filipino soldiers he had worked with in other contracts who were in the age range of fourteen to seventeen years old as “damn near as good as conscript-drafted Americans or Europeans in the use of NATO tactics.”62 Likewise, in Afghanistan, Northern Alliance commanders were quick to identify youngsters as among their best troops. In one report, an officer described a child soldier in his unit as the finest soldier he had ever commanded. The fifteen-year-old had been fighting since he was eleven and could hit a man in the head with an AK-47 from 200 meters (656 feet).63

Children make the best and bravest.… Don’t overlook them. They can fight more than we people. It is hard for them to just retreat.

—Liberian militia commander

Thus, as they build up combat experience, child soldier units can even coalesce into quite disciplined forces that can take on a professional force on their own terms. The elite of the entire LTTE force is the Sirasu Puli, or Leopard Brigade. Its members are children who have grown up in LTTE-run orphanages and have been taught from an early age to revere the group and its leaders. In December 1997 the Leopard Brigade fought a force of commandos from the Sri Lankan special forces, and was able to surround and kill nearly two hundred. This loss resonated further, demoralizing the entire Sri Lankan army, as these soldiers were the vanguard of the entire force.64 Similarly, the Okra Hills battle in 2000 between the British SAS and the West Side Boys in Sierra Leone was a hard-fought engagement lasting more than six hours. The British special forces, who are considered among the best soldiers in the world, won, but at a cost of more than twenty-five wounded and one killed. These were somewhat high numbers, considering that the SAS came in with an edge in training, technology, and equipment, and even had the element of surprise.65 As conflicts carry over for generations, child soldiers can grow up with the fighting. They can even form the nucleus of groups’ long-term fighting capabilities. In Uganda, for example, the core of Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army was a unit of three thousand children, including five hundred girls, who had been orphaned by the government’s earlier rampage in the Luwero triangle. They joined the rebels and were trained into one of its essential elements.66 Over the next decade they helped tiny Uganda carry an outsized influence in the Lakes region of Africa, often bullying its much larger neighbors. Likewise, the Red Army that the SPLA established in the 1980s was one of the sustaining factors in its decades-long fight against the government.

The lives that child soldiers lead can be terrifying and rife with danger. Moreover, most did not choose to lead it. Thus, for those outside this realm, it is difficult to conceptualize why they would stay in these groups and run such terrible risks. However, the child soldier doctrine has its deliberate sustaining factors. The very processes of recruitment and indoctrination are designed to bind the children to the group and, if this is not successful, prevent escape. The induction works to disconnect children from their old lives and commit them to the cause. Even if they want to leave, many may have no homes to return to or feel that they will not be welcomed back because of the violent acts they have committed. The physical tags, such as cropped hair, tattoos, or even scarring and branding, also make escapees easier to identify and recapture.

A sad reality is that many child soldiers do not want to leave their new lives. The general threshold appears to be a membership of one year or longer in the organization.67 This holds true even among abductees, who at the onset tend to define themselves as victims. After a period, though, the doctrine’s dark processes win out and the children’s own self-concept becomes entwined with their captors. The conditions are so adverse and indoctrination so persistent that the children can come to view themselves as members of the group. Some grow physically and psychologically addicted to the drugs their adult leaders supply. Others gain a sense of identity within the small units or even, somewhat surprisingly, develop the bonds of combat that keep them from deserting their fellow child soldiers.

I enjoyed the task of patrolling Kabul in a latest model jeep, with a Kalashnikov slung over my shoulder. It was a great adventure and made me feel big.

—M., age seventeen68

Researchers studying why soldiers stay in fights have often found that psychological factors are the most effective means of maintaining combat motivation and unit cohesion. A desire for acceptance from some community is often the one thing that holds soldiers together amid otherwise intolerable conditions. One of the most powerful of these is a sense of loyalty to one’s comrades.69 The same dynamic can happen even with child soldiers and lead them to stick with their groups.

Child soldier units can become bonded by their shared hardships and by the fact that they will have literally matured alongside each other. As one writer described an FMLN squad in El Salvador made up of thirteen- to nineteen-year-old girls and boys, “Together they are growing up. The common experiences they have had and the life they share now gives them a bond that is perhaps greater than if they were true blood siblings.”70 A reinforcing factor is that many of the children are orphans, meaning that their unit becomes their new family.

I had many friends in the bush. Whenever I fell behind during the fighting, they’d help me get back to my unit. One time, we were in the north, and we were attacked by the Kamajors [government-allied militia in Sierra Leone]. I was in a house, and I didn’t know what was going on. When I came out, one of my friends killed the Kamajor who wanted to kill me. It was timely … timely intervention. My friend shot the Kamajor and he fell. I ran towards the gutter, and another friend launched an RPG at the enemy, so I managed to escape. Without those two friends, I’d be dead.

—I., age twelve71

Four of us decided to escape because we were missing our family. We finally ended up in Freetown [Sierra Leone]. The others, they stayed in Makeni. They refused to come with us. They were hooked on cocaine, and they were enjoying life there in the bush.

—P., age twelve72

However, the critical factor that binds children to the group is fear. Escape is quite difficult. Fellow fighters, including other children, almost always surround them. These other troops are equally fearful of what will happen to them if they do not turn in the escapees. There is also the risk that, even if they are able to break away from their own small unit, escaping child soldiers will still run into other units in the field. Indeed, because of the decentralized nature of many rebel groups, many child soldiers have gone through a cycle of abduction and escape across different units and even sides.73

Escape is particularly hard for adolescent girls. Not only are they highly vulnerable to being taken advantage of while on the run, but they often have become pregnant while in captivity. This creates a further impediment that can either lead them to stay or have a more difficult time in their getaway. The result is that escapee figures are often significantly lower among girl child soldiers. In the LRA, for example, young women make up 40 percent of its total abductees but only 10 percent of its successful escapees.74

Even the prospect of a successful escape still carries many risks and can be deterring. This is especially so during a battle or when opposition soldiers are on patrol. The soldiers may be on edge from the ongoing fighting or fearful that the escapee is part of an ambush. In either case, they may have a shoot-first attitude that endangers escapees.

Once past these initial risks, the now former child soldiers’ ordeal is rarely over. Often, they find that they have nowhere to go. Their homes may have been destroyed; their parents may have been killed or may have fled to safer areas. Even those children who are able to find their homes or families may hesitate, fearing reprisals or ostracism by community members who blame the children for complicity in atrocities.

The underlying deterrent factor to escape, though, is the terrible punishment that will follow a failed escape attempt. Even for children within state armies, to flee is to commit desertion. Under most military codes of justice, this is punishable by long prison terms or even by facing a firing squad.

One boy tried to escape, but he was caught. His hands were tied, and then they made us, the other new captives, kill him with a stick. I felt sick. I knew this boy from before. We were from the same village. I refused to kill him and they told me they would shoot me. They pointed a gun at me, so I had to do it. The boy was asking me, “Why are you doing this?” I said I had no choice. After we killed him, they made us smear his blood on our arms. I felt dizzy. I felt so sick. They said we had to do this so we would not fear death and so we would not try to escape.

—S., age fifteen75

Rebel groups tend to use capital punishment more, as these groups are less bound by the law and need to send a stronger deterrent to maintain their numbers. The executions often are inclined to be ritualized and drawn out, as they present another opportunity for indoctrination. On the orders of their leaders, those children who attempt to flee and are caught are usually killed by other children. This is often carried out by as many as are present, to make all complicit. In most cases, the killing is done with handheld weapons to make it more personal for each executioner. The executioners are also typically forced to smear their arms and faces with the spilled blood of their victims. Other frightening techniques are used as well. The LRA, for instance, has had escapees tied to trees and burned alive in front of its young troops. In other cases, young soldiers have had to carry around the decomposing corpses of other young fighters who were killed while attempting escape.76

Still, despite these overwhelming risks, vast numbers of child soldiers run at every opportunity. Some hate their new lives, some do it out of terror, and some just miss their families. Of the thousands abducted, there are also thousands who have escaped. The majority of child soldiers interviewed have tried to escape at least once.77

I grew tired of seeing so many friends killed. It was four lost years, four years without a family.

—E., age seventeen78

We trained for five months in the training fields and were later taken to a place known as “Acholi” for further military training. As I was forced into the military [I coped with] whatever I was facing, but then I gave up hope and lost confidence in myself. [One night] I pretended to go to the latrine to defecate, and instead, I went directly into the bush. Some bodyguards fired at me, and I fell down and began rolling. They tried to confirm whether I was dead, but they didn’t find me. When I got up, I managed to cross the road and I moved and moved. The journey took me ten days, and on the way, I ate like an animal. Reaching Uganda’s border, I was assisted by a church leader, who gave me food and directed me to the UNHCR office.

—S., age unknown79

I tried to escape, but I was far away from my village. I didn’t know where I was. I made friends with another boy in my unit. He’s the one who told me how to escape. We left at night. We walked the whole night. We spent two days in the bush to escape from the rebels. But when I got to a village, the people arrested me. They beat me. They were going to kill me because I was a rebel, but my aunt saw me. She saved me.

—D., age sixteen80

The circumstances of these escapes are varied. While a number of former child soldiers claim to have planned their escape well beforehand, the majority state that they were simply waiting for an opportunity. The hold their organization had on them was short term, dependent on the tight observation commanders were able to keep on them. They went along with the program, but fled whenever a sudden opportunity presented itself—often in the heat and chaos of a military engagement. As explored further in Chapter 9, this hold is potentially a center of gravity for child soldier groups that can be exploited. Its breaking can help defeat these forces while minimizing the loss of life among children.