Mountain Hares were common during the last glacial period and evolved in open tundra. Today they inhabit heather moorland.

Mountain Hares were common during the last glacial period and evolved in open tundra. Today they inhabit heather moorland.

Evolution and Adaptations

Evolution has taken place over such a long time-scale and under such changing circumstances that it can be difficult to comprehend. The hares that exist today, like other mammals, evolved as a result of constantly changing environmental pressures over millions of years. They were faced with melting ice sheets, and changing sea levels, vegetation, and predators, but they survived. Hares became fast, open habitat specialists with special adaptations that help them to avoid predation.

Depending on exactly how you define mammals, they evolved around 170–225 million years ago. Mammals produce milk to feed their young and have special distinguishing features in their brains and bones; most mammals also have body hair.

Fossils suggest that the rabbit-like mammals separated from the rodent-like ones more than 50 million years ago in Asia, though the rabbit-like mammals were classified as rodents until 1912. Within the mammalian order Lagomorpha (rabbits, hares and pikas – mammalian herbivores with four incisors in their upper jaws), the Leporidae family (rabbits and hares, defined by their upright head posture and strong hind limbs) evolved about 53 million years ago in Asia, and spread into Eurasia about eight million years ago. The genus Lepus (hares) is first recognised in the fossil record about 2.6 million years ago in the northern hemisphere (north of the Tropic of Cancer).

This fossilised skull of an extinct species of lagomorph (Paleolagus haydeni) from North America looks similar to skulls of modern lagomorphs (see here).

Hares during the Ice Age

Fossils that have been collected in caves, potholes and muddy lakes suggest that Mountain Hares were probably already in the British Isles during the Wolstonian glaciation, which started around 352,000 years ago and ended 130,000 years ago. Archaeological remains found in what is now Belgium suggest that Mountain Hares were eaten by humans 28,000 years ago. But to understand the mammals found in Europe today, including hares, we have to look to more recent evolutionary history, since the maximum extent of ice during the last glacial period (the glacial maximum) about 20,000 years ago.

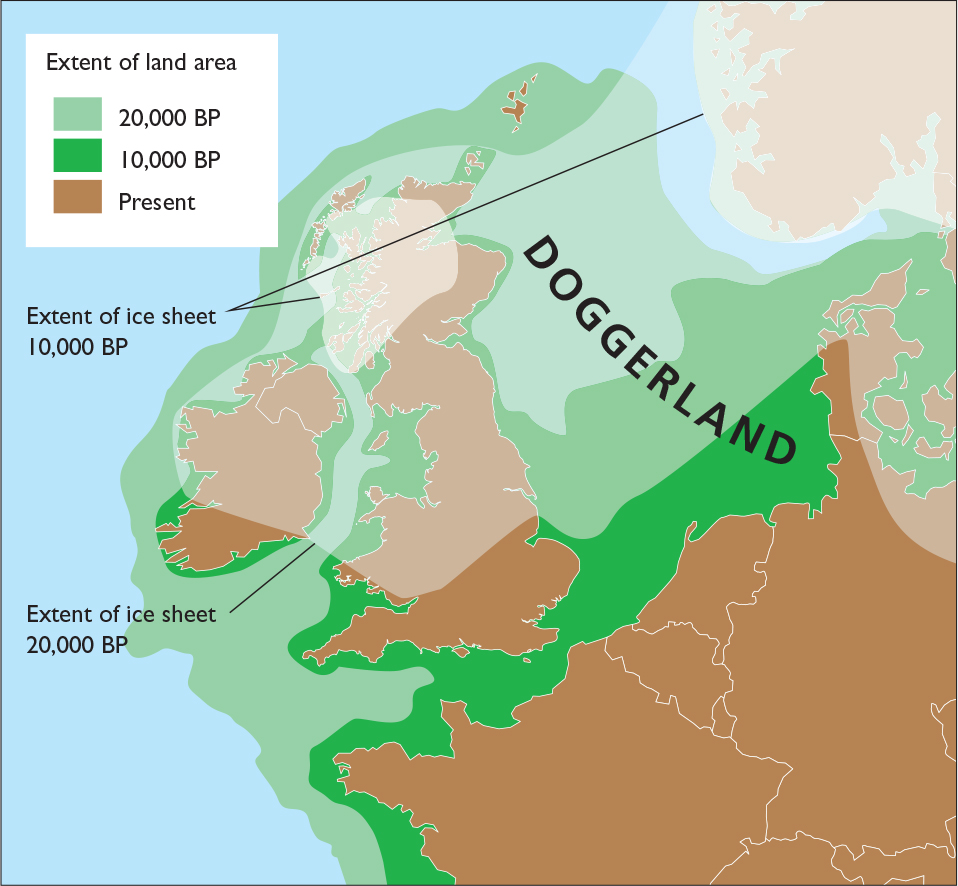

At that time, Great Britain was not an island; southern England, southern Ireland and continental Europe were connected by dry land, as sea levels were lower than today. Northern Britain was connected to Denmark, but both were covered with ice sheets. Ice covered northern Britain as far south as present-day North Yorkshire, down the east coast towards Norfolk, and extended in the west to South Wales and southern Ireland. An ice cap covered the mountains of southern Ireland; only a small part of Ireland remained ice-free. South of the ice sheet was bare tundra vegetation, where Mountain Hares probably felt quite at home – it was similar to the habitat they occupy today, and the habitat they evolved in.

Since the ice was at its maximum extent during the last glacial period 20,000 years ago (indicated by BP, before present), rising sea levels have resulted in changing coastlines in Europe. The retreating ice sheets were slowly replaced by forests, which were eventually cleared by humans.

Around 20,000 years ago, Mountain Hares were probably the most common and widespread hares in Europe, and their fossils have been found as far south as northern Spain. The Mountain Hare is one of a small handful of species still found in Britain today that could have survived the cold, harsh conditions here at the time. Other, more exotic species were also still present: Woolly Mammoths, Reindeer, Arctic Foxes, Woolly Rhinoceros, Lynx and Wild Horses. Fossilised bones from caves in England have cut marks showing that humans hunted Mountain Hares, for their fur or meat, approximately 12,000 years ago.

Melting ice sheets

After the retreat of the ice that began about 12,000 years ago, Europe slowly became covered in forest and so less suitable for hares. Mountain Hares gradually became restricted to areas with suitable habitats, and eventually only small, isolated relict populations remained in the Highlands of Scotland, parts of Ireland and the European Alps. The species’ main population developed from Scandinavia to eastern Siberia in the wake of the retreating ice sheet.

Mountain Hares in isolated relict populations may be becoming separate species.

The small populations of Mountain Hares that remained in Ireland and Scotland have been isolated from one another since long before the retreat of the ice and, as mentioned here, may be in the process of becoming separate species. This happens by natural selection. Those individuals most suited to life in Ireland and best able to survive and breed there are different from those most suited to life in Scotland. Conditions for the two populations are not the same, so eventually, over many generations, the hares end up being different enough to be considered separate species. On the Scottish island of Mull, Irish Hares were introduced in 1863, and Scottish Mountain Hares were released in 1864. The two groups are believed to have remained separate for at least 30 years, suggesting that they were (and are) different species.

Two Irish Hares (foreground, and back right) with a possible cross between an Irish Hare and a Brown Hare (back left). The possible hybrid has a grizzled coat typical of a Brown Hare, but in size and shape it is more like an Irish Hare.

The Brown Hare evolved as an animal of open steppe habitats. It probably survived the harsh conditions of the last glacial maximum in the area around the Black Sea, and spread through Europe during the last 12,000 years as humans turned forest into more open agricultural land. Brown Hare may have been introduced to Britain before Roman times, but it can be difficult to distinguish its archaeological remains from those of the Mountain Hare as skeletons are often damaged or incomplete. Older remains may belong to the Mountain Hare, which was already present in Britain. Therefore, it is not entirely clear whether the Brown Hare was introduced to Britain or made its own way across Doggerland, the land bridge that existed between England and Denmark until about 8,000 years ago.

Interbreeding

Hybrids may be born as a result of breeding between two animals or plants of different species (or genera, subspecies, etc.). Hybridisation between species is confusing – by definition it cannot occur, because species are often defined as groups of animals that can only breed with other members of the same group. Most of the time, members of different species do not interbreed, because speciation (the evolution of new species) has led to mechanisms to put them off each other. Members of different species don’t find each other attractive, their courtship behaviour is different, they smell ‘wrong’, the females’ eggs cannot be fertilised by the sperm of the other species, or the males’ penises are the wrong size or shape. Some taxonomists seem to be obsessed by measuring penises or penis bones (bacula), because differences in penis shape between species are often used to classify animals as belonging to different species, and taxonomists, like many other scientists, like working on things that can be measured.

Yet despite the preventative mechanisms, members of different species do sometimes mate. Often the offspring don’t survive or are infertile, but occasionally they are healthy, active and even able to breed themselves. This is most likely when the hybridising parents are closely related, such as with species of the same genus. In some cases (including in Lepus), hybridisation occurs mainly in one direction – males of one species mate with females of another – and happens less often the other way around. This is often because only big, strong males get to mate, while all females are able to mate: females are selective and prefer big males as mates. Therefore, the bigger species has an advantage as a male, but not as a female.

Left: A cross between a Lion and a Tiger, sometimes called a liger or a tigon.

Right: A cross between a Peregrine Falcon and a Merlin, sometimes called a perlin.

Hybridising hares

Brown Hares and Mountain Hares now mostly live in different habitats but, where they are found together, they sometimes interbreed (or hybridise). Since the two species are closely related, their offspring may be fertile.

Hybridisation can be very harmful, and may even lead to the local extinction of the Mountain Hare. In southern Sweden, since the introduction of the Brown Hare in the 1800s, the native Mountain Hare has become extinct over a huge area. Changes in habitat and climate may have been detrimenwtal for the Mountain Hare. However, Brown Hares are also bigger than Mountain Hares and are able to keep Mountain Hares away from food. In addition, male Brown Hares, being bigger than their rivals, are able to mate with female Mountain Hares; any female hybrid offspring also tend to mate with big Brown Hares. After a few generations, the animals look and behave like Brown Hares but have traces of Mountain Hare DNA to demonstrate their history of interbreeding. Eventually, few ‘pure’ Mountain Hares remain.

In Ireland, around 15 separate introductions of the Brown Hare were recorded between 1848 and 1892. Though many populations died out, the non-native species became established at two locations in Northern Ireland. In one of these locations, about half the hares are now Brown Hares, and the area occupied by Brown Hares in Northern Ireland increased substantially between 2005 and 2013. As in Sweden, they compete and hybridise with the native hares. Brown Hares constitute a serious and increasing threat to Irish Hares, and there are even calls to eradicate them from Ireland.

Traces of Mountain Hare DNA, providing evidence of past hybridisation, have been found in Brown Hares from various parts of Europe – the Iberian Peninsula, Russia and Sweden so far. Thus a genetic legacy from an Arctic species reveals to us its wider distribution thousands of years ago, when the climate was colder than today.

What makes a hare?

Blood vessels in the ears of a hare allow them to be used like car radiators, to cool the hare down.

Natural selection in countless generations of hares over the 6.2 million years of Lepus evolution has allowed them to become experts at surviving in open habitats, despite being attractive food for many predators. Some obvious and defining features of hares, essential to their success, are their long ears and back legs, and their excellent all-round eyesight.

Their long swivelling ears are multifunctional: they are used for acute directional hearing; as heat exchangers, allowing hot hares to cool down after running or in hot environments; as signals, to convey information to other hares, especially at dusk when their markings show up well; and as shock absorbers, to support the skull when hares are running at top speed. White markings on the tail also show up in low light and are used as social signals. Strong muscles in the large, extra-long back legs are adapted for powerful running, but also for fast and deft changes of direction: hares can jump, twist and turn to avoid capture. Brown Hares, when chased, are said to be able to run at 72km/h (45 miles/hour), while Mountain Hares can reach speeds of up to 64km/h (40 miles/hour).

Listening, looking and running: this hare is making good use of its senses.

Running hares can lift their tails to signal with the white markings. Their ears work as shock absorbers.

Hares have excellent all-round eyesight, enabling them to spot predators. Using their ears as shock absorbers allows them to see well while moving at speed over the terrain: their eyes are stabilised by their ears streaming out behind them as they run. Like many prey animals, hares have eyes on the sides of their heads, so that they can see behind them as well as to the side and in front. Hares have a keen sense of smell and use odour in communication. They also have a good sense of touch via their long whiskers; they use them when moving around to gauge the size of gaps in vegetation.

The contrasting markings on the backs of hares’ ears show up well, even at dusk, and are used as signals.

Hares have keen senses. Their eyes, like those of other prey animals, are positioned on the side of the head, allowing all-round vision. Their whiskers give them a good sense of touch.

Even while they’re grooming or scratching, hares are still checking for predators.

During the moult, in spring and autumn, hares can look scruffy. Patches of fur differing in length are particularly obvious on the head, as the fur is relatively short there. This Brown Hare is starting to moult. From the head, the moult will progress down and back to the rest of the body.