Chapter 8. Prettification: Layout and Styling, and What to Test About It

We’re starting to think about releasing the first version of our site, but we’re a bit embarrassed by how ugly it looks at the moment. In this chapter, we’ll cover some of the basics of styling, including integrating an HTML/CSS framework called Bootstrap. We’ll learn how static files work in Django, and what we need to do about testing them.

What to Functionally Test About Layout and Style

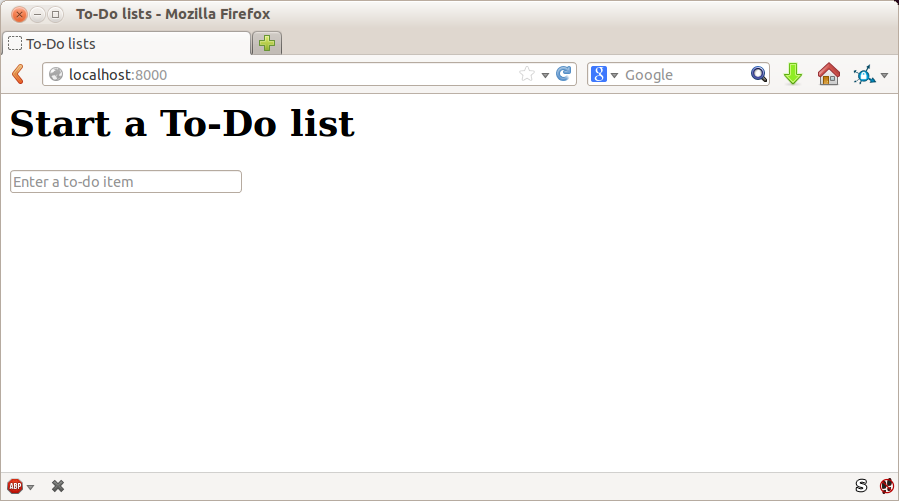

Our site is undeniably a bit unattractive at the moment (Figure 8-1).

Note

If you spin up your dev server with manage.py runserver, you

may run into a database error “table lists_item has no column named

list_id”. You need to update your local database to reflect the changes we

made in models.py. Use manage.py migrate. If it gives you any

grief about IntegrityErrors, just

delete1

the database file and try again.

We can’t be adding to Python’s reputation for being ugly, so let’s do a tiny bit of polishing. Here’s a few things we might want:

-

A nice large input field for adding new and existing lists

-

A large, attention-grabbing, centered box to put it in

How do we apply TDD to these things? Most people will tell you you shouldn’t test aesthetics, and they’re right. It’s a bit like testing a constant, in that tests usually wouldn’t add any value.

Figure 8-1. Our home page, looking a little ugly…

But we can test the implementation of our aesthetics—just enough to reassure ourselves that things are working. For example, we’re going to use Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) for our styling, and they are loaded as static files. Static files can be a bit tricky to configure (especially, as we’ll see later, when you move off your own PC and onto a hosting site), so we’ll want some kind of simple “smoke test” that the CSS has loaded. We don’t have to test fonts and colours and every single pixel, but we can do a quick check that the main input box is aligned the way we want it on each page, and that will give us confidence that the rest of the styling for that page is probably loaded too.

We start with a new test method inside our functional test:

functional_tests/tests.py (ch08l001)

classNewVisitorTest(LiveServerTestCase):[...]deftest_layout_and_styling(self):# Edith goes to the home pageself.browser.get(self.live_server_url)self.browser.set_window_size(1024,768)# She notices the input box is nicely centeredinputbox=self.browser.find_element_by_id('id_new_item')self.assertAlmostEqual(inputbox.location['x']+inputbox.size['width']/2,512,delta=10)

A few new things here. We start by setting the window size to a fixed

size. We then find the input element, look at its size and location, and

do a little maths to check whether it seems to be positioned in the middle

of the page. assertAlmostEqual helps us to deal with rounding errors and the

occasional weirdness due to scrollbars and the like, by letting us specify that

we want our arithmetic to work to within plus or minus 10 pixels.

If we run the functional tests, we get:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests

[...]

.F.

======================================================================

FAIL: test_layout_and_styling (functional_tests.tests.NewVisitorTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/.../superlists/functional_tests/tests.py", line 129, in

test_layout_and_styling

delta=10

AssertionError: 107.0 != 512 within 10 delta

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 3 tests in 9.188s

FAILED (failures=1)

That’s the expected failure. Still, this kind of FT is easy to get wrong, so let’s use a quick-and-dirty “cheat” solution, to check that the FT also passes when the input box is centered. We’ll delete this code again almost as soon as we’ve used it to check the FT:

lists/templates/home.html (ch08l002)

<formmethod="POST"action="/lists/new"><pstyle="text-align: center;"><inputname="item_text"id="id_new_item"placeholder="Enter a to-do item"/></p>{% csrf_token %}</form>

That passes, which means the FT works. Let’s extend it to make sure that the input box is also center-aligned on the page for a new list:

functional_tests/tests.py (ch08l003)

# She starts a new list and sees the input is nicely# centered there tooinputbox.send_keys('testing')inputbox.send_keys(Keys.ENTER)self.wait_for_row_in_list_table('1: testing')inputbox=self.browser.find_element_by_id('id_new_item')self.assertAlmostEqual(inputbox.location['x']+inputbox.size['width']/2,512,delta=10)

That gives us another test failure:

File "/.../superlists/functional_tests/tests.py", line 141, in

test_layout_and_styling

delta=10

AssertionError: 107.0 != 512 within 10 delta

Let’s commit just the FT:

$ git add functional_tests/tests.py $ git commit -m "first steps of FT for layout + styling"

Now it feels like we’re justified in finding a “proper” solution to our need

for some better styling for our site. We can back out our hacky

<p style="text-align: center">:

$ git reset --hard

Prettification: Using a CSS Framework

Design is hard, and doubly so now that we have to deal with mobile, tablets, and so forth. That’s why many programmers, particularly lazy ones like me, are turning to CSS frameworks to solve some of those problems for them. There are lots of frameworks out there, but one of the earliest and most popular is Twitter’s Bootstrap. Let’s use that.

You can find bootstrap at http://getbootstrap.com/.

We’ll download it and put it in a new folder called static inside the lists

app:2

$ wget -O bootstrap.zip https://github.com/twbs/bootstrap/releases/download/\ v3.3.4/bootstrap-3.3.4-dist.zip $ unzip bootstrap.zip $ mkdir lists/static $ mv bootstrap-3.3.4-dist lists/static/bootstrap $ rm bootstrap.zip

Bootstrap comes with a plain, uncustomised installation in the dist folder. We’re going to use that for now, but you should really never do this for a real site—vanilla Bootstrap is instantly recognisable, and a big signal to anyone in the know that you couldn’t be bothered to style your site. Learn how to use LESS and change the font, if nothing else! There is info in Bootstrap’s docs, or there’s a good guide here.

Our lists folder will end up looking like this:

$ tree lists lists ├── __init__.py ├── __pycache__ │ └── [...] ├── admin.py ├── models.py ├── static │ └── bootstrap │ ├── css │ │ ├── bootstrap.css │ │ ├── bootstrap.css.map │ │ ├── bootstrap.min.css │ │ ├── bootstrap-theme.css │ │ ├── bootstrap-theme.css.map │ │ └── bootstrap-theme.min.css │ ├── fonts │ │ ├── glyphicons-halflings-regular.eot │ │ ├── glyphicons-halflings-regular.svg │ │ ├── glyphicons-halflings-regular.ttf │ │ ├── glyphicons-halflings-regular.woff │ │ └── glyphicons-halflings-regular.woff2 │ └── js │ ├── bootstrap.js │ ├── bootstrap.min.js │ └── npm.js ├── templates │ ├── home.html │ └── list.html ├── tests.py ├── urls.py └── views.py

Look at the “Getting Started” section of the Bootstrap documentation; you’ll see it wants our HTML template to include something like this:

<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><metacharset="utf-8"><metahttp-equiv="X-UA-Compatible"content="IE=edge"><metaname="viewport"content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1"><title>Bootstrap 101 Template</title><!-- Bootstrap --><linkhref="css/bootstrap.min.css"rel="stylesheet"></head><body><h1>Hello, world!</h1><scriptsrc="http://code.jquery.com/jquery.js"></script><scriptsrc="js/bootstrap.min.js"></script></body></html>

We already have two HTML templates. We don’t want to be adding a whole load of boilerplate code to each, so now feels like the right time to apply the “Don’t repeat yourself” rule, and bring all the common parts together. Thankfully, the Django template language makes that easy using something called template inheritance.

Django Template Inheritance

Let’s have a little review of what the differences are between home.html and list.html:

$ diff lists/templates/home.html lists/templates/list.html

< <h1>Start a new To-Do list</h1>

< <form method="POST" action="/lists/new">

---

> <h1>Your To-Do list</h1>

> <form method="POST" action="/lists/{{ list.id }}/add_item">

[...]

> <table id="id_list_table">

> {% for item in list.item_set.all %}

> <tr><td>{{ forloop.counter }}: {{ item.text }}</td></tr>

> {% endfor %}

> </table>

They have different header texts, and their forms use different URLs. On top

of that, list.html has the additional <table> element.

Now that we’re clear on what’s in common and what’s not, we can make the two templates inherit from a common “superclass” template. We’ll start by making a copy of home.html:

$ cp lists/templates/home.html lists/templates/base.html

We make this into a base template which just contains the common boilerplate, and mark out the “blocks”, places where child templates can customise it:

lists/templates/base.html

<html><head><title>To-Do lists</title></head><body><h1>{% block header_text %}{% endblock %}</h1><formmethod="POST"action="{% block form_action %}{% endblock %}"><inputname="item_text"id="id_new_item"placeholder="Enter a to-do item"/>{% csrf_token %}</form>{% block table %} {% endblock %}</body></html>

The base template defines a series of areas called “blocks”, which will be places that other templates can hook in and add their own content. Let’s see how that works in practice, by changing home.html so that it “inherits from” base.html:

lists/templates/home.html

{% extends 'base.html' %}

{% block header_text %}Start a new To-Do list{% endblock %}

{% block form_action %}/lists/new{% endblock %}You can see that lots of the boilerplate HTML disappears, and we just concentrate on the bits we want to customise. We do the same for list.html:

lists/templates/list.html

{% extends 'base.html' %}

{% block header_text %}Your To-Do list{% endblock %}

{% block form_action %}/lists/{{ list.id }}/add_item{% endblock %}

{% block table %}

<table id="id_list_table">

{% for item in list.item_set.all %}

<tr><td>{{ forloop.counter }}: {{ item.text }}</td></tr>

{% endfor %}

</table>

{% endblock %}That’s a refactor of the way our templates work. We rerun the FTs to make sure we haven’t broken anything…

AssertionError: 107.0 != 512 within 10 delta

Sure enough, they’re still getting to exactly where they were before. That’s worthy of a commit:

$ git diff -b # the -b means ignore whitespace, useful since we've changed some html indenting $ git status $ git add lists/templates # leave static, for now $ git commit -m "refactor templates to use a base template"

Integrating Bootstrap

Now it’s much easier to integrate the boilerplate code that Bootstrap wants—we won’t add the JavaScript yet, just the CSS:

lists/templates/base.html (ch08l006)

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><metacharset="utf-8"><metahttp-equiv="X-UA-Compatible"content="IE=edge"><metaname="viewport"content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1"><title>To-Do lists</title><linkhref="css/bootstrap.min.css"rel="stylesheet"></head>[...]

Rows and Columns

Finally, let’s actually use some of the Bootstrap magic! You’ll have to read

the documentation yourself, but we should be able to use a combination

of the grid system and the text-center class to get what we want:

lists/templates/base.html (ch08l007)

<body><divclass="container"><divclass="row"><divclass="col-md-6 col-md-offset-3"><divclass="text-center"><h1>{% block header_text %}{% endblock %}</h1><formmethod="POST"action="{% block form_action %}{% endblock %}"><inputname="item_text"id="id_new_item"placeholder="Enter a to-do item"/>{% csrf_token %}</form></div></div></div><divclass="row"><divclass="col-md-6 col-md-offset-3">{% block table %} {% endblock %}</div></div></div></body>

(If you’ve never seen an HTML tag broken up over several lines, that <input>

may be a little shocking. It is definitely valid, but you don’t have to use

it if you find it offensive. ;)

Tip

Take the time to browse through the Bootstrap documentation, if you’ve never seen it before. It’s a shopping trolley brimming full of useful tools to use in your site.

Does that work?

AssertionError: 107.0 != 512 within 10 delta

Hmm. No. Why isn’t our CSS loading?

Static Files in Django

Django, and indeed any web server, needs to know two things to deal with static files:

-

How to tell when a URL request is for a static file, as opposed to for some HTML that’s going to be served via a view function

-

Where to find the static file the user wants

In other words, static files are a mapping from URLs to files on disk.

For item 1, Django lets us define a URL “prefix” to say that any URLs which start with that prefix should be treated as requests for static files. By default, the prefix is /static/. It’s defined in settings.py:

superlists/settings.py

[...]# Static files (CSS, JavaScript, Images)# https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.11/howto/static-files/STATIC_URL='/static/'

The rest of the settings we will add to this section are all to do with item 2: finding the actual static files on disk.

While we’re using the Django development server (manage.py runserver), we can

rely on Django to magically find static files for us—it’ll just look in any

subfolder of one of our apps called static.

You now see why we put all the Bootstrap static files into

lists/static. So why are they not working at the moment? It’s because we’re

not using the /static/ URL prefix. Have another look at the link to the CSS

in base.html:

<linkhref="css/bootstrap.min.css"rel="stylesheet">

To get this to work, we need to change it to:

lists/templates/base.html

<linkhref="/static/bootstrap/css/bootstrap.min.css"rel="stylesheet">

When runserver sees the request, it knows that it’s for a static file because

it begins with /static/. It then tries to find a file called

bootstrap/css/bootstrap.min.css, looking in each of our app folders for

subfolders called static, and it should find it at

lists/static/bootstrap/css/bootstrap.min.css.

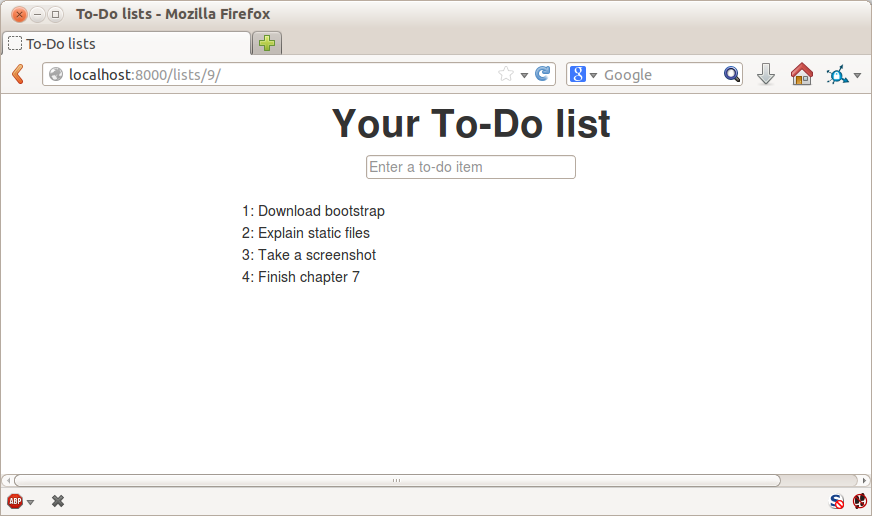

So if you take a look manually, you should see it works, as in Figure 8-2.

Figure 8-2. Our site starts to look a little better…

Switching to StaticLiveServerTestCase

If you run the FT though, it won’t pass:

AssertionError: 107.0 != 512 within 10 delta

That’s because, although runserver automagically finds static files,

LiveServerTestCase doesn’t. Never fear, though: the Django developers have

made a more magical test class called StaticLiveServerTestCase (see

the

docs).

Let’s switch to that:

functional_tests/tests.py

@@ -1,14 +1,14 @@-from django.test import LiveServerTestCase+from django.contrib.staticfiles.testing import StaticLiveServerTestCasefrom selenium import webdriver from selenium.common.exceptions import WebDriverException from selenium.webdriver.common.keys import Keys import time MAX_WAIT = 10-class NewVisitorTest(LiveServerTestCase):+class NewVisitorTest(StaticLiveServerTestCase):def setUp(self):

And now it will find the new CSS, which will get our test to pass:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests Creating test database for alias 'default'... ... --------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran 3 tests in 9.764s

Note

At this point, Windows users may see some (harmless, but distracting)

error messages that say socket.error: [WinError 10054] An existing

connection was forcibly closed by the remote host. Add a

self.browser.refresh() just before the self.browser.quit() in

tearDown to get rid of them. The issue is being tracked in a

bug on the Django tracker.

Hooray!

Using Bootstrap Components to Improve the Look of the Site

Let’s see if we can do even better, using some of the other tools in Bootstrap’s panoply.

Jumbotron!

Bootstrap has a class called jumbotron for things that are meant to be

particularly prominent on the page. Let’s use that to embiggen the main

page header and the input form:

lists/templates/base.html (ch08l009)

<divclass="col-md-6 col-md-offset-3 jumbotron"><divclass="text-center"><h1>{% block header_text %}{% endblock %}</h1><formmethod="POST"action="{% block form_action %}{% endblock %}">[...]

Tip

When hacking about with design and layout, it’s best to have a window open

that we can hit refresh on, frequently. Use python manage.py runserver

to spin up the dev server, and then browse to http://localhost:8000 to

see your work as we go.

Large Inputs

The jumbotron is a good start, but now the input box has tiny text compared to everything else. Thankfully, Bootstrap’s form control classes offer an option to set an input to be “large”:

lists/templates/base.html (ch08l010)

<inputname="item_text"id="id_new_item"class="form-control input-lg"placeholder="Enter a to-do item"/>

Using Our Own CSS

Finally I’d like to just offset the input from the title text slightly. There’s no ready-made fix for that in Bootstrap, so we’ll make one ourselves. That will require specifying our own CSS file:

lists/templates/base.html

[...]

<title>To-Do lists</title>

<link href="/static/bootstrap/css/bootstrap.min.css" rel="stylesheet">

<link href="/static/base.css" rel="stylesheet">

</head>We create a new file at lists/static/base.css, with our new CSS rule.

We’ll use the id of the input element, id_new_item, to find it and give it

some styling:

lists/static/base.css

#id_new_item {

margin-top: 2ex;

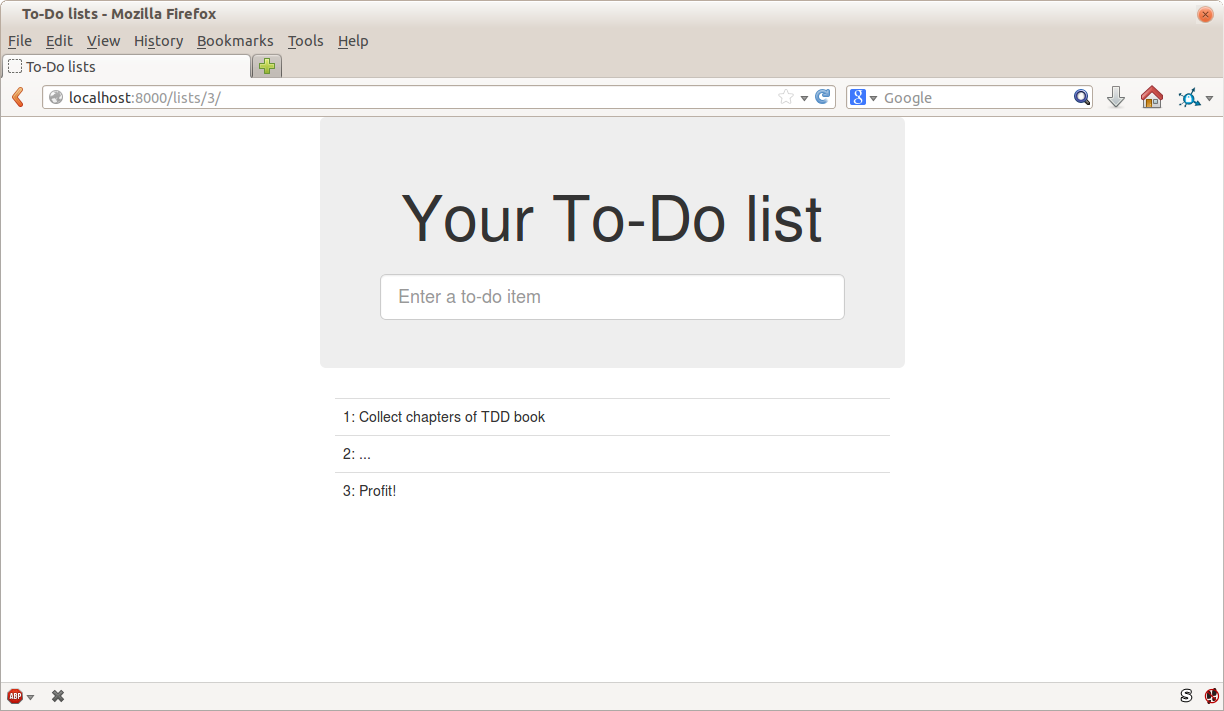

}All that took me a few goes, but I’m reasonably happy with it now (Figure 8-3).

If you want to go further with customising Bootstrap, you need to get into compiling LESS. I definitely recommend taking the time to do that some day. LESS and other pseudo-CSS-alikes like Sass are a great improvement on plain old CSS, and a useful tool even if you don’t use Bootstrap. I won’t cover it in this book, but you can find resources on the internets. Here’s one, for example.

A last run of the functional tests, to see if everything still works OK:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests [...] ... --------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran 3 tests in 10.084s OK

Figure 8-3. The lists page, with all big chunks…

That’s it! Definitely time for a commit:

$ git status # changes tests.py, base.html, list.html + untracked lists/static $ git add . $ git status # will now show all the bootstrap additions $ git commit -m "Use Bootstrap to improve layout"

What We Glossed Over: collectstatic and Other Static Directories

We saw earlier that the Django dev server will magically find all your static files inside app folders, and serve them for you. That’s fine during development, but when you’re running on a real web server, you don’t want Django serving your static content—using Python to serve raw files is slow and inefficient, and a web server like Apache or Nginx can do this all for you. You might even decide to upload all your static files to a CDN, instead of hosting them yourself.

For these reasons, you want to be able to gather up all your static files from

inside their various app folders, and copy them into a single location, ready

for deployment. This is what the collectstatic command is for.

The destination, the place where the collected static files go, is defined in

settings.py as STATIC_ROOT. In the next chapter we’ll be doing some

deployment, so let’s actually experiment with that now. We’ll change its value

to a folder just outside our repo—I’m going to make it a folder just next to

the main source folder:

workspace │ ├── superlists │ │ ├── lists │ │ │ ├── models.py │ │ │ │ │ ├── manage.py │ │ ├── superlists │ │ │ ├── static │ │ ├── base.css │ │ ├── etc...

The logic is that the static files folder shouldn’t be a part of your repository—we don’t want to put it under source control, because it’s a duplicate of all the files that are inside lists/static.

Here’s a neat way of specifying that folder, making it relative to the location of the project base directory:

superlists/settings.py (ch08l018)

# Static files (CSS, JavaScript, Images)# https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.11/howto/static-files/STATIC_URL='/static/'STATIC_ROOT=os.path.abspath(os.path.join(BASE_DIR,'../static'))

Take a look at the top of the settings file, and you’ll see how that BASE_DIR

variable is helpfully defined for us, using __file__ (which itself is a

really, really useful Python built-in).

Anyway, let’s try running collectstatic:

$ python manage.py collectstatic [...] Copying '/.../superlists/lists/static/bootstrap/css/bootstrap-theme.css' Copying '/.../superlists/lists/static/bootstrap/css/bootstrap.min.css' 76 static files copied to '/.../static'.

And if we look in ../static, we’ll find all our CSS files:

$ tree ../static/

../static/

├── admin

│ ├── css

│ │ ├── base.css

[...]

│ └── xregexp.min.js

├── base.css

└── bootstrap

├── css

│ ├── bootstrap.css

│ ├── bootstrap.css.map

│ ├── bootstrap.min.css

│ ├── bootstrap-theme.css

│ ├── bootstrap-theme.css.map

│ └── bootstrap-theme.min.css

├── fonts

│ ├── glyphicons-halflings-regular.eot

│ ├── glyphicons-halflings-regular.svg

│ ├── glyphicons-halflings-regular.ttf

│ ├── glyphicons-halflings-regular.woff

│ └── glyphicons-halflings-regular.woff2

└── js

├── bootstrap.js

├── bootstrap.min.js

└── npm.js

14 directories, 76 files

collectstatic has also picked up all the CSS for the admin site. It’s one of

Django’s powerful features, and we’ll find out all about it one day, but we’re

not ready to use that yet, so let’s disable it for now:

superlists/settings.py

INSTALLED_APPS=[#'django.contrib.admin','django.contrib.auth','django.contrib.contenttypes','django.contrib.sessions','django.contrib.messages','django.contrib.staticfiles','lists',]

And we try again:

$ rm -rf ../static/ $ python manage.py collectstatic --noinput Copying '/.../superlists/lists/static/base.css' [...] Copying '/.../superlists/lists/static/bootstrap/css/bootstrap-theme.css' Copying '/.../superlists/lists/static/bootstrap/css/bootstrap.min.css' 15 static files copied to '/.../static'.

Much better.

Anyway, now we know how to collect all the static files into a single folder, where it’s easy for a web server to find them. We’ll find out all about that, including how to test it, in the next chapter!

For now let’s save our changes to settings.py:

$ git diff # should show changes in settings.py* $ git commit -am "set STATIC_ROOT in settings and disable admin"

A Few Things That Didn’t Make It

Inevitably this was only a whirlwind tour of styling and CSS, and there were several topics that I’d considered covering that didn’t make it. Here are a few candidates for further study:

-

Customising bootstrap with LESS or SASS

-

The

{% static %}template tag, for more DRY and fewer hardcoded URLs -

Client-side packaging tools, like

npmandbower

1 What? Delete the database? Are you crazy? Not completely. The local dev database often gets out of sync with its migrations as we go back and forth in our development, and it doesn’t have any important data in it, so it’s OK to blow it away now and again. We’ll be much more careful once we have a “production” database on the server. More on this in Appendix D.

2 On Windows, you may not have wget and unzip, but I’m sure you can figure out how to download Bootstrap, unzip it, and put the contents of the dist folder into the lists/static/bootstrap folder.