Chapter 9. Testing Deployment Using a Staging Site

Is all fun and game until you are need of put it in production.

It’s time to deploy the first version of our site and make it public. They say that if you wait until you feel ready to ship, then you’ve waited too long.

Is our site usable? Is it better than nothing? Can we make lists on it? Yes, yes, yes.

No, you can’t log in yet. No, you can’t mark tasks as completed. But do we really need any of that stuff? Not really—and you can never be sure what your users are actually going to do with your site once they get their hands on it. We think our users want to use the site for to-do lists, but maybe they actually want to use it to make “top 10 best fly-fishing spots” lists, for which you don’t need any kind of “mark completed” function. We won’t know until we put it out there.

In this chapter we’re going to go through and actually deploy our site to a real, live web server.

You might be tempted to skip this chapter—there’s lots of daunting stuff in it, and maybe you think this isn’t what you signed up for. But I strongly urge you to give it a go. This is one of the sections of the book I’m most pleased with, and it’s one that people often write to me saying they were really glad they stuck through it.

If you’ve never done a server deployment before, it will demystify a whole world for you, and there’s nothing like the feeling of seeing your site live on the actual internet. Give it a buzzword name like “DevOps” if that’s what it takes to convince you it’s worth it.

Note

Why not ping me a note once your site is live on the web, and send me the URL? It always gives me a warm and fuzzy feeling… obeythetestinggoat@gmail.com.

TDD and the Danger Areas of Deployment

Deploying a site to a live web server can be a tricky topic. Oft-heard is the forlorn cry “but it works on my machine!”

Some of the danger areas of deployment include:

- Static files (CSS, JavaScript, images, etc.)

-

Web servers usually need special configuration for serving these.

- The database

-

There can be permissions and path issues, and we need to be careful about preserving data between deploys.

- Dependencies

-

We need to make sure that the packages our software relies on are installed on the server, and have the correct versions.

But there are solutions to all of these. In order:

-

Using a staging site, on the same infrastructure as the production site, can help us test out our deployments and get things right before we go to the “real” site.

-

We can also run our functional tests against the staging site. That will reassure us that we have the right code and packages on the server, and since we now have a “smoke test” for our site layout, we’ll know that the CSS is loaded correctly.

-

Just like on our own PC, a virtualenv is useful on the server for managing packages and dependencies when you might be running more than one Python application.

-

And finally, automation, automation, automation. By using an automated script to deploy new versions, and by using the same script to deploy to staging and production, we can reassure ourselves that staging is as much like live as possible.1

Over the next few pages I’m going to go through a deployment procedure. It isn’t meant to be the perfect deployment procedure, so please don’t take it as being best practice, or a recommendation—it’s meant to be an illustration, to show the kinds of issues involved in deployment and where testing fits in.

As Always, Start with a Test

Let’s adapt our functional tests slightly so that it can be run against a staging site. We’ll do it by slightly hacking an argument that is normally used to change the address which the test’s temporary server gets run on:

functional_tests/tests.py (ch08l001)

importos[...]classNewVisitorTest(StaticLiveServerTestCase):defsetUp(self):self.browser=webdriver.Firefox()staging_server=os.environ.get('STAGING_SERVER')ifstaging_server:self.live_server_url='http://'+staging_server

Do you remember I said that LiveServerTestCase had certain limitations?

Well, one is that it always assumes you want to use its own test server, which

it makes available at self.live_server_url. I still want to be able to do

that sometimes, but I also want to be able to selectively tell it not to

bother, and to use a real server instead.

The way I decided to do it is using an environment variable called

STAGING_SERVER.

Here’s the hack: we replace

self.live_server_urlwith the address of our “real” server.

We test that said hack hasn’t broken anything by running the functional tests “normally”:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests [...] Ran 3 tests in 8.544s OK

And now we can try them against our staging server URL. I’m planning to host my staging server at superlists-staging.ottg.eu:

$ STAGING_SERVER=superlists-staging.ottg.eu python manage.py test functional_tests

======================================================================

FAIL: test_can_start_a_list_for_one_user

(functional_tests.tests.NewVisitorTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/.../superlists/functional_tests/tests.py", line 49, in

test_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later

self.assertIn('To-Do', self.browser.title)

AssertionError: 'To-Do' not found in 'Domain name registration | Domain names

| Web Hosting | 123-reg'

[...]

======================================================================

FAIL: test_multiple_users_can_start_lists_at_different_urls

(functional_tests.tests.NewVisitorTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File

"/.../superlists/functional_tests/tests.py", line 86, in

test_layout_and_styling

inputbox = self.browser.find_element_by_id('id_new_item')

[...]

selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate

element: [id="id_new_item"]

[...]

======================================================================

FAIL: test_layout_and_styling (functional_tests.tests.NewVisitorTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File

[...]

selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate

element: [id="id_new_item"]

[...]

Ran 3 tests in 19.480s:

FAILED (failures=3)

Note

If, on Windows, you see an error saying something like “STAGING_SERVER is not recognized as a command”, it’s probably because you’re not using Git-Bash. Take another look at the “Prerequisites and Assumptions” section.

You can see that both tests are failing, as expected, since I haven’t actually set up my domain yet. In fact, you can see from the first traceback that the test is actually ending up on the home page of my domain registrar.

The FT seems to be testing the right things though, so let’s commit:

$ git diff # should show changes to functional_tests.py $ git commit -am "Hack FT runner to be able to test staging"

Tip

Don’t use export to set the STAGING_SERVER environment variable;

otherwise, all your subsequent test runs in that terminal will be against

staging (and that can be very confusing if you’re not expecting it).

Setting it explicitly inline each time you run the FTs is best.

Getting a Domain Name

We’re going to need a couple of domain names at this point in the book—they can both be subdomains of a single domain. I’m going to use superlists.ottg.eu and superlists-staging.ottg.eu. If you don’t already own a domain, this is the time to register one! Again, this is something I really want you to actually do. If you’ve never registered a domain before, just pick any old registrar and buy a cheap one—it should only cost you $5 or so, and you can even find free ones. I promise seeing your site on a “real” website will be a thrill.

Manually Provisioning a Server to Host Our Site

We can separate out “deployment” into two tasks:

-

Provisioning a new server to be able to host the code

-

Deploying a new version of the code to an existing server

Some people like to use a brand new server for every deployment—it’s what we do at PythonAnywhere. That’s only necessary for larger, more complex sites though, or major changes to an existing site. For a simple site like ours, it makes sense to separate the two tasks. And, although we eventually want both to be completely automated, we can probably live with a manual provisioning system for now.

As you go through this chapter, you should be aware that provisioning is something that varies a lot, and that as a result there are few universal best practices for deployment. So, rather than trying to remember the specifics of what I’m doing here, you should be trying to understand the rationale, so that you can apply the same kind of thinking in the specific future circumstances you encounter.

Choosing Where to Host Our Site

There are loads of different solutions out there these days, but they broadly fall into two camps:

-

Running your own (possibly virtual) server

-

Using a Platform-As-A-Service (PaaS) offering like Heroku, OpenShift, or PythonAnywhere

Particularly for small sites, a PaaS offers a lot of advantages, and I would definitely recommend looking into them. We’re not going to use a PaaS in this book however, for several reasons. Firstly, I have a conflict of interest, in that I think PythonAnywhere is the best, but then again I would say that because I work there. Secondly, all the PaaS offerings are quite different, and the procedures to deploy to each vary a lot—learning about one doesn’t necessarily tell you about the others. Any one of them might change their process radically, or simply go out of business by the time you get to read this book.

Instead, we’ll learn just a tiny bit of good old-fashioned server admin, including SSH and web server config. They’re unlikely to ever go away, and knowing a bit about them will get you some respect from all the grizzled dinosaurs out there.

What I have done is to try to set up a server in such a way that it’s a lot like the environment you get from a PaaS, so you should be able to apply the lessons we learn in the deployment section, no matter what provisioning solution you choose.

Spinning Up a Server

I’m not going to dictate how you do this—whether you choose Amazon AWS, Rackspace, Digital Ocean, your own server in your own data centre or a Raspberry Pi in a cupboard under the stairs, any solution should be fine, as long as:

-

Your server is running Ubuntu 16.04 (aka “Xenial/LTS”).

-

You have root access to it.

-

It’s on the public internet.

-

You can SSH into it.

I’m recommending Ubuntu as a distro because it’s easy to get Python 3.6 on it and it has some specific ways of configuring Nginx, which I’m going to make use of next. If you know what you’re doing, you can probably get away with using something else, but you’re on your own.

If you’ve never started a Linux server before and you have absolutely no idea where to start, I wrote a very brief guide on GitHub.

Note

Some people get to this chapter, and are tempted to skip the domain bit, and the “getting a real server” bit, and just use a VM on their own PC. Don’t do this. It’s not the same, and you’ll have more difficulty following the instructions, which are complicated enough as it is. If you’re worried about cost, dig around and you’ll find free options for both. Email me if you need further pointers; I’m always happy to help.

User Accounts, SSH, and Privileges

In these instructions, I’m assuming that you have a nonroot user account set up that has “sudo” privileges, so whenever we need to do something that requires root access, we use sudo, and I’m explicit about that in the various instructions that follow.

My user is called “elspeth”, but you can call yours whatever you like!

Installing Nginx

We’ll need a web server, and all the cool kids are using Nginx these days, so we will too. Having fought with Apache for many years, I can tell you it’s a blessed relief in terms of the readability of its config files, if nothing else!

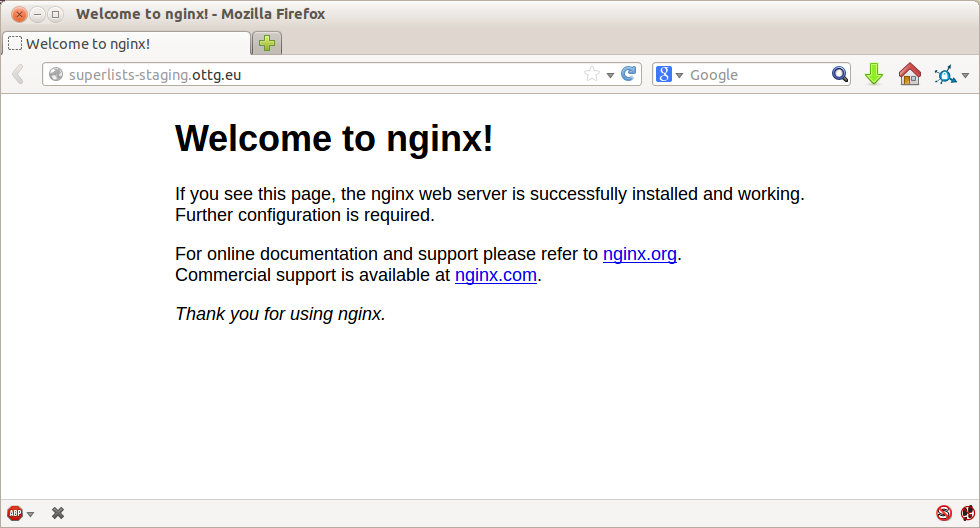

Installing Nginx on my server was a matter of doing an apt-get, and I could

then see the default Nginx “Hello World” screen:

elspeth@server:$ sudo apt-get install nginx elspeth@server:$ sudo systemctl start nginx

(You may need to do an apt-get update and/or an apt-get upgrade first.)

Tip

Look out for that elspeth@server in the command-line listings in this

chapter. It indicates commands that must be run on the server, as opposed

to commands you run on your own PC.

You should be able to go to the IP address of your server, and see the “Welcome to nginx” page at this point, as in Figure 9-1.

Tip

If you don’t see it, it may be because your firewall does not open port 80 to the world. On AWS, for example, you may need to configure the “security group” for your server to open port 80.

Figure 9-1. Nginx—it works!

Installing Python 3.6

Python 3.6 wasn’t available in the standard repositories on Ubuntu at the time of writing, but the user-contributed “Deadsnakes PPA” has it. Here’s how we install it:

While we’ve got root access, let’s make sure the server has the key pieces of software we need at the system level: Python, Git, pip, and virtualenv.

elspeth@server:$ sudo add-apt-repository ppa:fkrull/deadsnakes elspeth@server:$ sudo apt-get update elspeth@server:$ sudo apt-get install python3.6 python3.6-venv

And while we’re at it, we’ll just make sure Git is installed too.

elspeth@server:$ sudo apt-get install git

Configuring Domains for Staging and Live

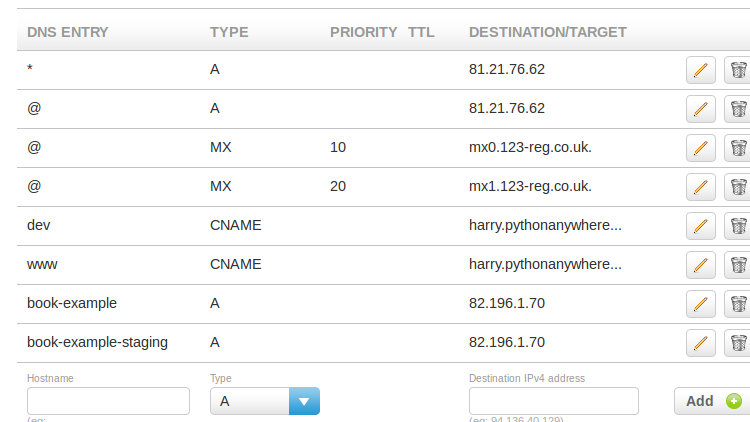

We don’t want to be messing about with IP addresses all the time, so we should point our staging and live domains to the server. At my registrar, the control screens looked a bit like Figure 9-2.

Figure 9-2. Domain setup

In the DNS system, pointing a domain at a specific IP address is called an “A-Record”. All registrars are slightly different, but a bit of clicking around should get you to the right screen in yours.

Using the FT to Confirm the Domain Works and Nginx Is Running

To confirm this works, we can rerun our functional tests and see that their failure messages have changed slightly—one of them in particular should now mention Nginx:

$ STAGING_SERVER=superlists-staging.ottg.eu python manage.py test functional_tests [...] selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate element: [id="id_new_item"] [...] AssertionError: 'To-Do' not found in 'Welcome to nginx!'

Progress! Give yourself a pat on the back, and maybe a nice cup of tea and a Chocolate biscuit.

Deploying Our Code Manually

The next step is to get a copy of the staging site up and running, just to check whether we can get Nginx and Django to talk to each other. As we do so, we’re starting to move into doing “deployment” rather than provisioning, so we should be thinking about how we can automate the process as we go.

Note

One rule of thumb for distinguishing provisioning from deployment is that you tend to need root permissions for the former, but you don’t for the latter.

We need a directory for the source to live in. We’ll put it somewhere in the home folder of our nonroot user; in my case it would be at /home/elspeth (this is likely to be the setup on any shared hosting system, but you should always run your web apps as a nonroot user, in any case). I’m going to set up my sites like this:

/home/elspeth ├── sites │ ├── www.live.my-website.com │ │ ├── database │ │ │ └── db.sqlite3 │ │ ├── source │ │ │ ├── manage.py │ │ │ ├── superlists │ │ │ ├── etc... │ │ │ │ │ ├── static │ │ │ ├── base.css │ │ │ ├── etc... │ │ │ │ │ └── virtualenv │ │ ├── lib │ │ ├── etc... │ │ │ ├── www.staging.my-website.com │ │ ├── database │ │ ├── etc...

Each site (staging, live, or any other website) has its own folder. Within that

we have a separate folder for the source code, the database, and the static

files. The logic is that, while the source code might change from one version

of the site to the next, the database will stay the same. The static folder

is in the same relative location, ../static, that we set up at the end of

the last chapter. Finally, the virtualenv gets its own subfolder too (on the

server, there’s no need to use virtualenvwrapper; we’ll create a virtualenv

manually).

Adjusting the Database Location

First let’s change the location of our database in settings.py, and make sure we can get that working on our local PC:

superlists/settings.py (ch08l003)

# Build paths inside the project like this: os.path.join(BASE_DIR, ...)importosBASE_DIR=os.path.dirname(os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(__file__)))[...]DATABASES={'default':{'ENGINE':'django.db.backends.sqlite3','NAME':os.path.join(BASE_DIR,'../database/db.sqlite3'),}}

Tip

Check out the way BASE_DIR is defined, further up in settings.py.

Notice the abspath gets done first (i.e., innermost). Always follow this

pattern when path wrangling; otherwise, you can see strange things happening

depending on how the file is imported. Thanks to

Green Nathan for that tip!

Now let’s try it locally:

$ mkdir ../database $ python manage.py migrate --noinput Operations to perform: Apply all migrations: auth, contenttypes, lists, sessions Running migrations: [...] $ ls ../database/ db.sqlite3

That seems to work. Let’s commit it:

$ git diff # should show changes in settings.py $ git commit -am "move sqlite database outside of main source tree"

To get our code onto the server, we’ll use Git and go via one of the code-sharing sites. If you haven’t already, push your code up to GitHub, BitBucket, or similar. They all have excellent instructions for beginners on how to do that.

Here are some bash commands that will set this all up. If you’re not familiar

with it, note the export command which lets me set up a “local variable”

in bash:

elspeth@server:$ export SITENAME=superlists-staging.ottg.eu elspeth@server:$ mkdir -p ~/sites/$SITENAME/database elspeth@server:$ mkdir -p ~/sites/$SITENAME/static elspeth@server:$ mkdir -p ~/sites/$SITENAME/virtualenv # you should replace the URL in the next line with the URL for your own repo elspeth@server:$ git clone https://github.com/hjwp/book-example.git \ ~/sites/$SITENAME/source Resolving deltas: 100% [...]

Note

A bash variable defined using export only lasts as long as that console

session. If you log out of the server and log back in again, you’ll need to

redefine it. It’s devious because Bash won’t error, it will just substitute

the empty string for the variable, which will lead to weird results…if in

doubt, do a quick echo $SITENAME.

Now we’ve got the site installed, let’s just try running the dev server—this is a smoke test, to see if all the moving parts are connected:

elspeth@server:$ $ cd ~/sites/$SITENAME/source

$ python manage.py runserver

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "manage.py", line 8, in <module>

from django.core.management import execute_from_command_line

ImportError: No module named django.core.management

Ah. Django isn’t installed on the server.

Creating a Virtualenv Manually, and Using requirements.txt

To “save” the list of packages we need in our virtualenv, and be able to re-create it on the server, we create a requirements.txt file:

$ echo "django==1.11" > requirements.txt $ git add requirements.txt $ git commit -m "Add requirements.txt for virtualenv"

Note

You may be wondering why we didn’t add our other dependency, Selenium, to our requirements. The reason is that Selenium is only a dependency for the tests, not the application code. Some people like to also create a file called test-requirements.txt.

Now we do a git push to send our updates up to our code-sharing site:

$ git push

And we can pull those changes down to the server:

elspeth@server:$ git pull # may ask you to do some git config first

Creating a virtualenv “manually” (i.e., without virtualenvwrapper) involves

using the standard library “venv” module, and specifying the path you

want the virtualenv to go in:

elspeth@server:$ pwd /home/espeth/sites/staging.superlists.com/source elspeth@server:$ python3.6 -m venv ../virtualenv elspeth@server:$ ls ../virtualenv/bin activate activate.fish easy_install-3.6 pip3 python activate.csh easy_install pip pip3.6 python3

If we wanted to activate the virtualenv, we could do so with

source ../virtualenv/bin/activate, but we don’t need to do

that. We can actually do everything we want to by calling the versions

of Python, pip, and the other executables in the virtualenv’s bin

directory, as we’ll see.

To install our requirements into the virtualenv, we use the virtualenv pip:

elspeth@server:$ ../virtualenv/bin/pip install -r requirements.txt Downloading/unpacking Django==1.11 (from -r requirements.txt (line 1)) [...] Successfully installed Django

And to run Python in the virtualenv, we use the virtualenv python

binary:

elspeth@server:$ ../virtualenv/bin/python manage.py runserver Validating models... 0 errors found [...]

Tip

Depending on your firewall configuration, you may even be able to manually

visit your site at this point. You’ll need to run runserver 0.0.0.0:8000

to listen on the public as well as private IP address, and then go to

http://your.domain.com:8000.

That looks like it’s running happily. We can Ctrl-C it for now.

More progress! We’ve got a system for getting code to and from the server (git push and git pull), and we’ve got a virtualenv set up to match our local one, and

a single file, requirements.txt, to keep them in sync.

Next we’ll configure the Nginx web server to talk to Django and get our site up on the standard port 80.

Simple Nginx Configuration

We create an Nginx config file to tell it to send requests for our staging site along to Django. A minimal config looks like this:

server: /etc/nginx/sites-available/superlists-staging.ottg.eu

server{listen80;server_namesuperlists-staging.ottg.eu;location/{proxy_passhttp://localhost:8000;}}

This config says it will only listen for our staging domain, and will “proxy” all requests to the local port 8000 where it expects to find Django waiting to respond.

I saved this to a file called superlists-staging.ottg.eu inside the /etc/nginx/sites-available folder.

Note

Not sure how to edit a file on the server? There’s always vi, which I’ll

keep encouraging you to learn a bit of, but perhaps today is already too

full of new things. Try the relatively beginner-friendly

nano

instead. Note you’ll also need to use sudo because the file is in a

system folder.

We then add it to the enabled sites for the server by creating a symlink to it:

elspeth@server:$ echo $SITENAME # check this still has our site in superlists-staging.ottg.eu elspeth@server:$ sudo ln -s ../sites-available/$SITENAME /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/$SITENAME elspeth@server:$ ls -l /etc/nginx/sites-enabled # check our symlink is there

That’s the Debian/Ubuntu preferred way of saving Nginx configurations—the real config file in sites-available, and a symlink in sites-enabled; the idea is that it makes it easier to switch sites on or off.

We also may as well remove the default “Welcome to nginx” config, to avoid any confusion:

elspeth@server:$ sudo rm /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/default

And now to test it:

elspeth@server:$ sudo systemctl reload nginx elspeth@server:$ ../virtualenv/bin/python manage.py runserver

Note

I also had to edit /etc/nginx/nginx.conf and uncomment a line saying

server_names_hash_bucket_size 64; to get my long domain name to work.

You may not have this problem; Nginx will warn you when you do a reload

if it has any trouble with its config files.

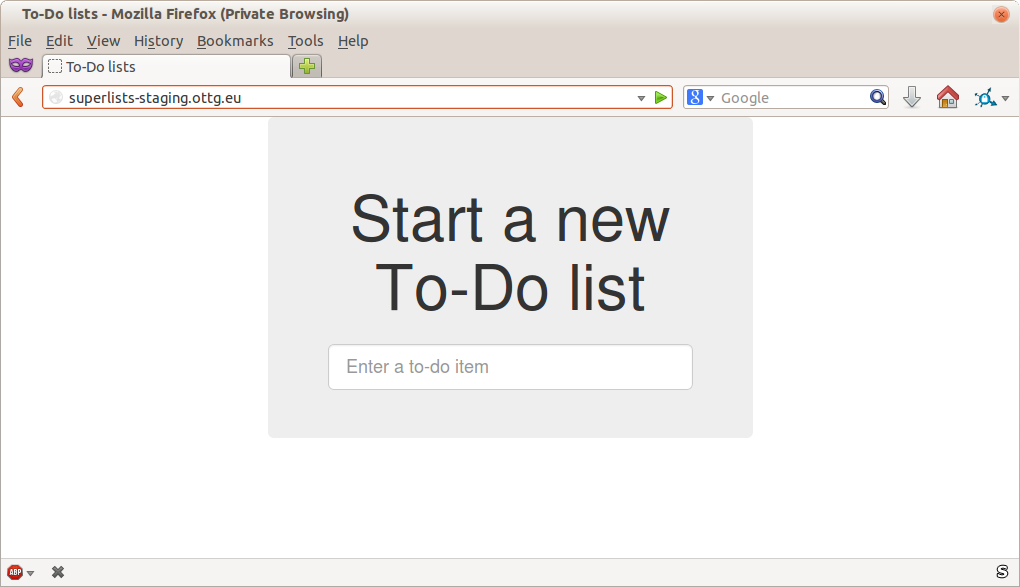

A quick visual inspection confirms—the site is up (Figure 9-3)!

Figure 9-3. The staging site is up!

Tip

If you ever find Nginx isn’t behaving as expected, try the command

sudo nginx -t, which does a config test, and will warn you of any

problems in your configuration files.

Let’s see what our functional tests say:

$ STAGING_SERVER=superlists-staging.ottg.eu python manage.py test functional_tests [...] selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate [...] AssertionError: 0.0 != 512 within 3 delta

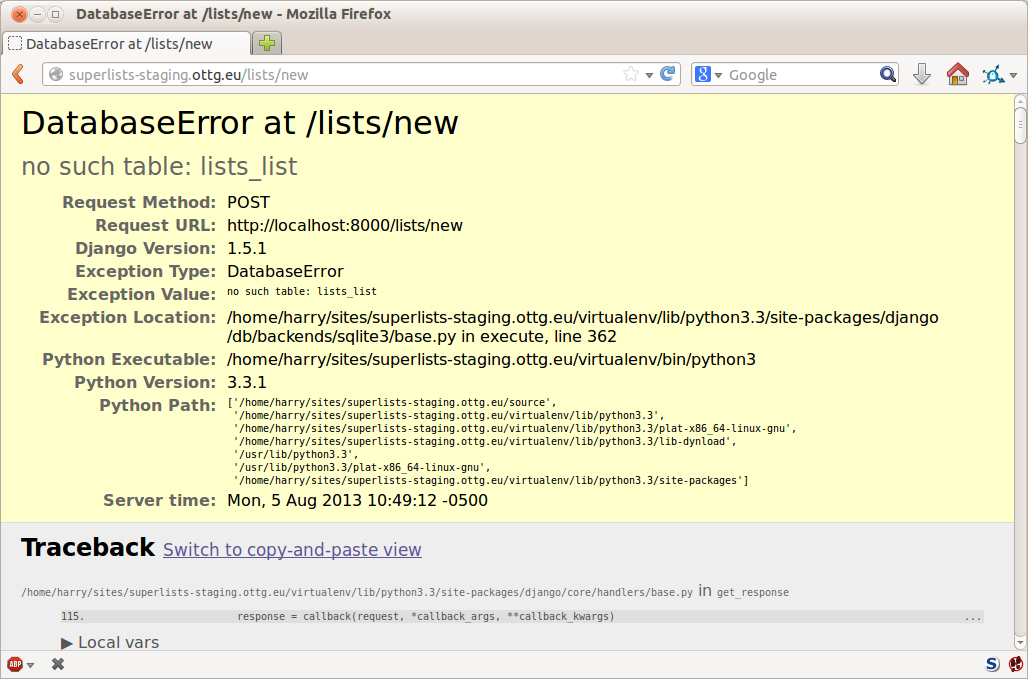

The tests are failing as soon as they try to submit a new item, because we haven’t set up the database. You’ll probably have spotted the yellow Django debug page (Figure 9-4) telling us as much as the tests went through, or if you tried it manually.

Figure 9-4. But the database isn’t

Note

The tests saved us from potential embarrassment there. The site looked fine when we loaded its front page. If we’d been a little hasty, we might have thought we were done, and it would have been the first users that discovered that nasty Django DEBUG page. Okay, slight exaggeration for effect, maybe we would have checked, but what happens as the site gets bigger and more complex? You can’t check everything. The tests can.

Creating the Database with migrate

We run migrate using the --noinput argument to suppress the two little “are

you sure” prompts:

elspeth@server:$ ../virtualenv/bin/python manage.py migrate --noinput Creating tables ... [...] elspeth@server:$ ls ../database/ db.sqlite3 elspeth@server:$ ../virtualenv/bin/python manage.py runserver

Let’s try the FTs again:

$ STAGING_SERVER=superlists-staging.ottg.eu python manage.py test functional_tests [...] ... --------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran 3 tests in 10.718s OK

It’s great to see the site up and running! We might reward ourselves with a well-earned tea break at this point, before moving on to the next section…

Tip

If you see a “502 - Bad Gateway”, it’s probably because you forgot to

restart the dev server with manage.py runserver after the migrate.

There are a few more debugging tips in the sidebar that follows.

Success! Our Hack Deployment Works

Phew. Assuming you managed to get that up and running, we are at least

reassured that the basic piping works, but we really can’t be using the Django

dev server in production. We also can’t be relying on

manually starting it up with runserver. In the next chapter, we’ll

make our hacky deployment more production-ready.

1 What I’m calling a “staging” server, some people would call a “development” server, and some others would also like to distinguish “preproduction” servers. Whatever we call it, the point is to have somewhere we can try our code out in an environment that’s as similar as possible to the real production server.