Chapter 19. Using Mocks to Test External Dependencies or Reduce Duplication

In this chapter we’ll start testing the parts of our code that send emails.

In the FT, you saw that Django gives us a way of retrieving any emails it

sends by using the mail.outbox attribute. But in this chapter, I want

to demonstrate a very important testing technique called mocking, so for

the purpose of these unit tests, we’ll pretend that this nice Django shortcut

doesn’t exist.

Note

Am I telling you not to use Django’s mail.outbox? No; use it, it’s a

neat shortcut. But I want to teach mocks because they’re a useful

general-purpose tool for unit testing external dependencies. You

may not always be using Django! And even if you are, you may not

be sending email—any interaction with a third-party API is a good

candidate for testing with mocks.

Before We Start: Getting the Basic Plumbing In

Let’s just get a basic view and URL set up first. We can do so with a simple test that our new URL for sending the login email should eventually redirect back to the home page:

accounts/tests/test_views.py

fromdjango.testimportTestCaseclassSendLoginEmailViewTest(TestCase):deftest_redirects_to_home_page(self):response=self.client.post('/accounts/send_login_email',data={'email':'edith@example.com'})self.assertRedirects(response,'/')

Wire up the include in superlists/urls.py, plus the url in

accounts/urls.py, and get the test passing with something a bit like this:

accounts/views.py

fromdjango.core.mailimportsend_mailfromdjango.shortcutsimportredirectdefsend_login_email(request):returnredirect('/')

I’ve added the import of the send_mail function as a placeholder for now:

$ python manage.py test accounts [...] Ran 4 tests in 0.015s OK

OK, now we have a starting point, so let’s get mocking!

Mocking Manually, aka Monkeypatching

When we call send_mail in real life we expect Django to be making a

connection to our email provider, and sending an actual email across the public

internet. That’s not something we want to happen in our tests. It’s a similar

problem whenever you have code that has external side effects—calling an

API, sending out a tweet or an SMS or whatever it may be. In our unit tests, we

don’t want to be sending out real tweets or API calls across the internet. But

we would still like a way of testing that our code is correct.

Mocks1

are the answer.

Actually, one of the great things about Python is that its dynamic nature makes

it very easy to do things like mocking, or what’s sometimes called

monkeypatching. Let’s suppose

that, as a first step, we want to get to some code that invokes send_mail

with the right subject line, from address, and to address. That would look

something like this:

accounts/views.py

defsend_login_email(request):=request.POST['email']# send_mail(# 'Your login link for Superlists',# 'body text tbc',# 'noreply@superlists',# [email],# )returnredirect('/')

How can we test this, without calling the real send_mail function? The

answer is that our test can ask Python to replace the send_mail function with

a fake version, at runtime, before we invoke the send_login_email view.

Check this out:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l005)

fromdjango.testimportTestCaseimportaccounts.viewsclassSendLoginEmailViewTest(TestCase):[...]deftest_sends_mail_to_address_from_post(self):self.send_mail_called=Falsedeffake_send_mail(subject,body,from_email,to_list):self.send_mail_called=Trueself.subject=subjectself.body=bodyself.from_email=from_emailself.to_list=to_listaccounts.views.send_mail=fake_send_mailself.client.post('/accounts/send_login_email',data={'':'edith@example.com'})self.assertTrue(self.send_mail_called)self.assertEqual(self.subject,'Your login link for Superlists')self.assertEqual(self.from_email,'noreply@superlists')self.assertEqual(self.to_list,['edith@example.com'])

We define a

fake_send_mailfunction, which looks like the realsend_mailfunction, but all it does is save some information about how it was called, using some variables onself.

Then, before we execute the code under test by doing the

self.client.post, we swap out the realaccounts.views.send_mailwith our fake version—it’s as simple as just assigning it.

It’s important to realise that there isn’t really anything magical going on here; we’re just taking advantage of Python’s dynamic nature and scoping rules.

Up until we actually invoke a function, we can modify the variables it has

access to, as long as we get into the right namespace (that’s why we import the

top-level accounts module, to be able to get down to the accounts.views module,

which is the scope that the accounts.views.send_login_email function will run

in).

This isn’t even something that only works inside unit tests. You can do this kind of “monkeypatching” in any kind of Python code!

That may take a little time to sink in. See if you can convince yourself that it’s not all totally crazy, before reading a couple of bits of further detail.

-

Why do we use

selfas a way of passing information around? It’s just a convenient variable that’s available both inside the scope of thefake_send_mailfunction and outside of it. We could use any mutable object, like a list or a dictionary, as long as we are making in-place changes to an existing variable that exists outside our fake function. (Feel free to have a play around with different ways of doing this, if you’re curious, and see what works and doesn’t work.) -

The “before” is critical! I can’t tell you how many times I’ve sat there, wondering why a mock isn’t working, only to realise that I didn’t mock before I called the code under test.

Let’s see if our hand-rolled mock object will let us test-drive some code:

$ python manage.py test accounts

[...]

self.assertTrue(self.send_mail_called)

AssertionError: False is not true

So let’s call send_mail, naively:

accounts/views.py

defsend_login_email(request):send_mail()returnredirect('/')

That gives:

TypeError: fake_send_mail() missing 4 required positional arguments: 'subject', 'body', 'from_email', and 'to_list'

Looks like our monkeypatch is working! We’ve called send_mail, and it’s gone

into our fake_send_mail function, which wants more arguments. Let’s try

this:

accounts/views.py

defsend_login_email(request):send_mail('subject','body','from_email',['to email'])returnredirect('/')

That gives:

self.assertEqual(self.subject, 'Your login link for Superlists') AssertionError: 'subject' != 'Your login link for Superlists'

That’s working pretty well. And now we can work all the way through to something like this:

accounts/views.py

defsend_login_email(request):=request.POST['email']send_mail('Your login link for Superlists','body text tbc','noreply@superlists',[])returnredirect('/')

and passing tests!

$ python manage.py test accounts Ran 5 tests in 0.016s OK

Brilliant! We’ve managed to write tests for some code, that

ordinarily2 would go out and try to send real emails across the internet,

and by “mocking out” the send_email function, we’re able to write

the tests and code all the same.

The Python Mock Library

The popular mock package was added to the standard library as part of Python

3.3.3

It provides a magical object called a Mock; try this out in a Python shell:

>>>fromunittest.mockimportMock>>>m=Mock()>>>m.any_attribute<Mockname='mock.any_attribute'id='140716305179152'>>>>type(m.any_attribute)<class'unittest.mock.Mock'>>>>m.any_method()<Mockname='mock.any_method()'id='140716331211856'>>>>m.foo()<Mockname='mock.foo()'id='140716331251600'>>>>m.calledFalse>>>m.foo.calledTrue>>>m.bar.return_value=1>>>m.bar(42,var='thing')1>>>m.bar.call_argscall(42,var='thing')

A magical object that responds to any request for an attribute or method call with other mocks, that you can configure to return specific values for its calls, and that allows you to inspect what it was called with? Sounds like a useful thing to be able to use in our unit tests!

Using unittest.patch

And as if that weren’t enough, the mock module also provides a helper

function called patch, which we can use to do the monkeypatching we did

by hand earlier.

I’ll explain how it all works shortly, but let’s see it in action first:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l007)

fromdjango.testimportTestCasefromunittest.mockimportpatch[...]@patch('accounts.views.send_mail')deftest_sends_mail_to_address_from_post(self,mock_send_mail):self.client.post('/accounts/send_login_email',data={'email':'edith@example.com'})self.assertEqual(mock_send_mail.called,True)(subject,body,from_email,to_list),kwargs=mock_send_mail.call_argsself.assertEqual(subject,'Your login link for Superlists')self.assertEqual(from_email,'noreply@superlists')self.assertEqual(to_list,['edith@example.com'])

If you rerun the tests, you’ll see they still pass. And since we’re always suspicious of any test that still passes after a big change, let’s deliberately break it just to see:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l008)

self.assertEqual(to_list,['schmedith@example.com'])

And let’s add a little debug print to our view:

accounts/views.py (ch17l009)

defsend_login_email(request):=request.POST['email'](type(send_mail))send_mail([...]

And run the tests again:

$ python manage.py test accounts [...] <class 'function'> <class 'unittest.mock.MagicMock'> [...] AssertionError: Lists differ: ['edith@example.com'] != ['schmedith@example.com'] [...] Ran 5 tests in 0.024s FAILED (failures=1)

Sure enough, the tests fail. And we can see just before the failure

message that when we print the type of the send_mail function,

in the first unit test it’s a normal function, but in the second unit

test we’re seeing a mock object.

Let’s remove the deliberate mistake and dive into exactly what’s going on:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l011)

@patch('accounts.views.send_mail')deftest_sends_mail_to_address_from_post(self,mock_send_mail):self.client.post('/accounts/send_login_email',data={'':'edith@example.com'})self.assertEqual(mock_send_mail.called,True)(subject,body,from_email,to_list),kwargs=mock_send_mail.call_argsself.assertEqual(subject,'Your login link for Superlists')self.assertEqual(from_email,'noreply@superlists')self.assertEqual(to_list,['edith@example.com'])

The

patchdecorator takes a dot-notation name of an object to monkeypatch. That’s the equivalent of manually replacing thesend_mailinaccounts.views. The advantage of the decorator is that, firstly, it automatically replaces the target with a mock. And secondly, it automatically puts the original object back at the end! (Otherwise, the object stays monkeypatched for the rest of the test run, which might cause problems in other tests.)

patchthen injects the mocked object into the test as an argument to the test method. We can choose whatever name we want for it, but I usually use a convention ofmock_plus the original name of the object.

We call our function under test as usual, but everything inside this test method has our mock applied to it, so the view won’t call the real

send_mailobject; it’ll be seeingmock_send_mailinstead.

And we can now make assertions about what happened to that mock object during the test. We can see it was called…

…and we can also unpack its various positional and keyword call arguments, and examine what it was called with. (We’ll discuss

call_argsin a bit more detail later.)

All crystal-clear? No? Don’t worry, we’ll do a couple more tests with mocks, to see if they start to make more sense as we use them more.

Getting the FT a Little Further Along

First let’s get back to our FT and see where it’s failing:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests.test_login [...] AssertionError: 'Check your email' not found in 'Superlists\nEnter email to log in:\nStart a new To-Do list'

Submitting the email address currently has no effect, because the form isn’t sending the data anywhere. Let’s wire it up in base.html:4

lists/templates/base.html (ch17l012)

<formclass="navbar-form navbar-right"method="POST"action="{% url 'send_login_email' %}">

Does that help? Nope, same error. Why? Because we’re not actually displaying a success message after we send the user an email. Let’s add a test for that.

Testing the Django Messages Framework

We’ll use Django’s “messages framework”, which is often used to display ephemeral “success” or “warning” messages to show the results of an action. Have a look at the django messages docs if you haven’t come across it already.

Testing Django messages is a bit contorted—we have to pass follow=True to

the test client to tell it to get the page after the 302-redirect, and examine

its context for a list of messages (which we have to listify before it’ll

play nicely). Here’s what it looks like:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l013)

deftest_adds_success_message(self):response=self.client.post('/accounts/send_login_email',data={'email':'edith@example.com'},follow=True)message=list(response.context['messages'])[0]self.assertEqual(message.message,"Check your email, we've sent you a link you can use to log in.")self.assertEqual(message.tags,"success")

That gives:

$ python manage.py test accounts

[...]

message = list(response.context['messages'])[0]

IndexError: list index out of range

And we can get it passing with:

accounts/views.py (ch17l014)

fromdjango.contribimportmessages[...]defsend_login_email(request):[...]messages.success(request,"Check your email, we've sent you a link you can use to log in.")returnredirect('/')

Adding Messages to Our HTML

What happens next in the functional test? Ah. Still nothing. We need to actually add the messages to the page. Something like this:

lists/templates/base.html (ch17l015)

[...]

</nav>

{% if messages %}

<div class="row">

<div class="col-md-8">

{% for message in messages %}

{% if message.level_tag == 'success' %}

<div class="alert alert-success">{{ message }}</div>

{% else %}

<div class="alert alert-warning">{{ message }}</div>

{% endif %}

{% endfor %}

</div>

</div>

{% endif %}Now do we get a little further? Yes!

$ python manage.py test accounts [...] Ran 6 tests in 0.023s OK $ python manage.py test functional_tests.test_login [...] AssertionError: 'Use this link to log in' not found in 'body text tbc'

We need to fill out the body text of the email, with a link that the user can use to log in.

Let’s just cheat for now though, by changing the value in the view:

accounts/views.py

send_mail('Your login link for Superlists','Use this link to log in','noreply@superlists',[])

That gets the FT a little further:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests.test_login [...] AssertionError: Could not find url in email body: Use this link to log in

Starting on the Login URL

We’re going to have to build some kind of URL! Let’s build one that, again, just cheats:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l017)

classLoginViewTest(TestCase):deftest_redirects_to_home_page(self):response=self.client.get('/accounts/login?token=abcd123')self.assertRedirects(response,'/')

We’re imagining we’ll pass the token in as a GET parameter, after the ?.

It doesn’t need to do anything for now.

I’m sure you can find your way through to getting the boilerplate for a basic URL and view in, via errors like these:

-

No URL:

AssertionError: 404 != 302 : Response didn't redirect as expected: Response code was 404 (expected 302)

-

No view:

AttributeError: module 'accounts.views' has no attribute 'login'

-

Broken view:

ValueError: The view accounts.views.login didn't return an HttpResponse object. It returned None instead.

-

OK!

$ python manage.py test accounts [...] Ran 7 tests in 0.029s OK

And now we can give them a link to use. It still won’t do much though, because we still don’t have a token to give to the user.

Checking That We Send the User a Link with a Token

Back in our send_login_email view, we’ve tested the email subject, from, and

to fields. The body is the part that will have to include a token or URL they

can use to log in. Let’s spec out two tests for that:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l021)

fromaccounts.modelsimportToken[...]deftest_creates_token_associated_with_email(self):self.client.post('/accounts/send_login_email',data={'email':'edith@example.com'})token=Token.objects.first()self.assertEqual(token.,'edith@example.com')@patch('accounts.views.send_mail')deftest_sends_link_to_login_using_token_uid(self,mock_send_mail):self.client.post('/accounts/send_login_email',data={'email':'edith@example.com'})token=Token.objects.first()expected_url=f'http://testserver/accounts/login?token={token.uid}'(subject,body,from_email,to_list),kwargs=mock_send_mail.call_argsself.assertIn(expected_url,body)

The first test is fairly straightforward; it checks that the token we create in the database is associated with the email address from the post request.

The second one is our second test using mocks. We mock out the send_mail

function again using the patch decorator, but this time we’re interested

in the body argument from the call arguments.

Running them now will fail because we’re not creating any kind of token:

$ python manage.py test accounts [...] AttributeError: 'NoneType' object has no attribute 'email' [...] AttributeError: 'NoneType' object has no attribute 'uid'

We can get the first one to pass by creating a token:

accounts/views.py (ch17l022)

fromaccounts.modelsimportToken[...]defsend_login_email(request):=request.POST['email']token=Token.objects.create(=)send_mail([...]

And now the second test prompts us to actually use the token in the body of our email:

[...] AssertionError: 'http://testserver/accounts/login?token=[...] not found in 'Use this link to log in' FAILED (failures=1)

So we can insert the token into our email like this:

accounts/views.py (ch17l023)

fromdjango.core.urlresolversimportreverse[...]defsend_login_email(request):=request.POST['']token=Token.objects.create(=)url=request.build_absolute_uri(reverse('login')+'?token='+str(token.uid))message_body=f'Use this link to log in:\n\n{url}'send_mail('Your login link for Superlists',message_body,'noreply@superlists',[])[...]

request.build_absolute_urideserves a mention—it’s one way to build a “full” URL, including the domain name and the http(s) part, in Django. There are other ways, but they usually involve getting into the “sites” framework, and that gets overcomplicated pretty quickly. You can find lots more discussion on this if you’re curious by doing a bit of googling.

Two more pieces in the puzzle. We need an authentication backend, whose job it will be to examine tokens for validity and then return the corresponding users; then we need to get our login view to actually log users in, if they can authenticate.

De-spiking Our Custom Authentication Backend

Our custom authentication backend is next. Here’s how it looked in the spike:

classPasswordlessAuthenticationBackend(object):defauthenticate(self,uid):('uid',uid,file=sys.stderr)ifnotToken.objects.filter(uid=uid).exists():('no token found',file=sys.stderr)returnNonetoken=Token.objects.get(uid=uid)('got token',file=sys.stderr)try:user=ListUser.objects.get(=token.)('got user',file=sys.stderr)returnuserexceptListUser.DoesNotExist:('new user',file=sys.stderr)returnListUser.objects.create(=token.)defget_user(self,):returnListUser.objects.get(=)

Decoding this:

-

We take a UID and check if it exists in the database.

-

We return

Noneif it doesn’t. -

If it does exist, we extract an email address, and either find an existing user with that address, or create a new one.

1 if = 1 More Test

A rule of thumb for these sorts of tests: any if means an extra test, and

any try/except means an extra test, so this should be about three tests.

How about something like this?

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py

fromdjango.testimportTestCasefromdjango.contrib.authimportget_user_modelfromaccounts.authenticationimportPasswordlessAuthenticationBackendfromaccounts.modelsimportTokenUser=get_user_model()classAuthenticateTest(TestCase):deftest_returns_None_if_no_such_token(self):result=PasswordlessAuthenticationBackend().authenticate('no-such-token')self.assertIsNone(result)deftest_returns_new_user_with_correct_email_if_token_exists(self):='edith@example.com'token=Token.objects.create(=)user=PasswordlessAuthenticationBackend().authenticate(token.uid)new_user=User.objects.get(=)self.assertEqual(user,new_user)deftest_returns_existing_user_with_correct_email_if_token_exists(self):='edith@example.com'existing_user=User.objects.create(=)token=Token.objects.create(=)user=PasswordlessAuthenticationBackend().authenticate(token.uid)self.assertEqual(user,existing_user)

In authenticate.py we’ll just have a little placeholder:

accounts/authentication.py

classPasswordlessAuthenticationBackend(object):defauthenticate(self,uid):pass

How do we get on?

$ python manage.py test accounts

.FE.........

======================================================================

ERROR: test_returns_new_user_with_correct_email_if_token_exists

(accounts.tests.test_authentication.AuthenticateTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/.../superlists/accounts/tests/test_authentication.py", line 21, in

test_returns_new_user_with_correct_email_if_token_exists

new_user = User.objects.get(email=email)

[...]

accounts.models.DoesNotExist: User matching query does not exist.

======================================================================

FAIL: test_returns_existing_user_with_correct_email_if_token_exists

(accounts.tests.test_authentication.AuthenticateTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/.../superlists/accounts/tests/test_authentication.py", line 30, in

test_returns_existing_user_with_correct_email_if_token_exists

self.assertEqual(user, existing_user)

AssertionError: None != <User: User object>

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 12 tests in 0.038s

FAILED (failures=1, errors=1)

Here’s a first cut:

accounts/authentication.py (ch17l026)

fromaccounts.modelsimportUser,TokenclassPasswordlessAuthenticationBackend(object):defauthenticate(self,uid):token=Token.objects.get(uid=uid)returnUser.objects.get(=token.)

That gets one test passing but breaks another one:

$ python manage.py test accounts ERROR: test_returns_None_if_no_such_token (accounts.tests.test_authentication.AuthenticateTest) accounts.models.DoesNotExist: Token matching query does not exist. ERROR: test_returns_new_user_with_correct_email_if_token_exists (accounts.tests.test_authentication.AuthenticateTest) [...] accounts.models.DoesNotExist: User matching query does not exist.

Let’s fix each of those in turn:

accounts/authentication.py (ch17l027)

defauthenticate(self,uid):try:token=Token.objects.get(uid=uid)returnUser.objects.get(=token.)exceptToken.DoesNotExist:returnNone

That gets us down to one failure:

ERROR: test_returns_new_user_with_correct_email_if_token_exists (accounts.tests.test_authentication.AuthenticateTest) [...] accounts.models.DoesNotExist: User matching query does not exist. FAILED (errors=1)

And we can handle the final case like this:

accounts/authentication.py (ch17l028)

defauthenticate(self,uid):try:token=Token.objects.get(uid=uid)returnUser.objects.get(=token.)exceptUser.DoesNotExist:returnUser.objects.create(=token.)exceptToken.DoesNotExist:returnNone

That’s turned out neater than our spike!

The get_user Method

We’ve handled the authenticate function which Django will use to log new

users in. The second part of the protocol we have to implement is the

get_user method, whose job is to retrieve a user based on their unique

identifier (the email address), or to return None if it can’t find one

(have another look at the spiked code if you need a

reminder).

Here are a couple of tests for those two requirements:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py (ch17l030)

classGetUserTest(TestCase):deftest_gets_user_by_email(self):User.objects.create(='another@example.com')desired_user=User.objects.create(='edith@example.com')found_user=PasswordlessAuthenticationBackend().get_user('edith@example.com')self.assertEqual(found_user,desired_user)deftest_returns_None_if_no_user_with_that_email(self):self.assertIsNone(PasswordlessAuthenticationBackend().get_user('edith@example.com'))

And our first failure:

AttributeError: 'PasswordlessAuthenticationBackend' object has no attribute 'get_user'

Let’s create a placeholder one then:

accounts/authentication.py (ch17l031)

classPasswordlessAuthenticationBackend(object):defauthenticate(self,uid):[...]defget_user(self,):pass

Now we get:

self.assertEqual(found_user, desired_user) AssertionError: None != <User: User object>

And (step by step, just to see if our test fails the way we think it will):

accounts/authentication.py (ch17l033)

defget_user(self,):returnUser.objects.first()

That gets us past the first assertion, and onto:

self.assertEqual(found_user, desired_user) AssertionError: <User: User object> != <User: User object>

And so we call get with the email as an argument:

accounts/authentication.py (ch17l034)

defget_user(self,):returnUser.objects.get(=)

Now our test for the None case fails:

ERROR: test_returns_None_if_no_user_with_that_email [...] accounts.models.DoesNotExist: User matching query does not exist.

Which prompts us to finish the method like this:

accounts/authentication.py (ch17l035)

defget_user(self,):try:returnUser.objects.get(=)exceptUser.DoesNotExist:returnNone

You could just use

passhere, and the function would returnNoneby default. However, because we specifically need the function to returnNone, the “explicit is better than implicit” rule applies here.

That gets us to passing tests:

OK

And we have a working authentication backend!

Using Our Auth Backend in the Login View

The final step is to use the backend in our login view. First we add it to settings.py:

superlists/settings.py (ch17l036)

AUTH_USER_MODEL='accounts.User'AUTHENTICATION_BACKENDS=['accounts.authentication.PasswordlessAuthenticationBackend',][...]

Next let’s write some tests for what should happen in our view. Looking back at the spike again:

accounts/views.py

deflogin(request):('login view',file=sys.stderr)uid=request.GET.get('uid')user=auth.authenticate(uid=uid)ifuserisnotNone:auth.login(request,user)returnredirect('/')

We need the view to call django.contrib.auth.authenticate, and then,

if it returns a user, we call django.contrib.auth.login.

Tip

This is a good time to check out the Django docs on authentication for a little more context.

An Alternative Reason to Use Mocks: Reducing Duplication

So far we’ve used mocks to test external dependencies, like Django’s mail-sending function. The main reason to use a mock was to isolate ourselves from external side effects, in this case, to avoid sending out actual emails during our tests.

In this section we’ll look at a different kind of use of mocks. Here we don’t have any side effects we’re worried about, but there are still some reasons you might want to use a mock here.

The nonmocky way of testing this login view would be to see whether it does actually log the user in, by checking whether the user gets assigned an authenticated session cookie in the right circumstances.

But our authentication backend does have a few different code paths:

it returns None for invalid tokens, existing users if they already exist,

and creates new users for valid tokens if they don’t exist yet. So, to fully

test this view, I’d have to write tests for all three of those cases.

Tip

One good justification for using mocks is when they will reduce duplication between tests. It’s one way of avoiding combinatorial explosion.

On top of that, the fact that we’re using the Django

auth.authenticate function rather than calling our own code directly is

relevant: it allows us the option to add further backends in future.

So in this case (in contrast to the example in “Mocks Can Leave You Tightly Coupled to the Implementation”) the implementation does matter, and using a mock will save us from having duplication in our tests. Let’s see how it looks:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l037)

fromunittest.mockimportpatch,call[...]@patch('accounts.views.auth')deftest_calls_authenticate_with_uid_from_get_request(self,mock_auth):self.client.get('/accounts/login?token=abcd123')self.assertEqual(mock_auth.authenticate.call_args,call(uid='abcd123'))

We expect to be using the

django.contrib.authmodule in views.py, and we mock it out here. Note that this time, we’re not mocking out a function, we’re mocking out a whole module, and thus implicitly mocking out all the functions (and any other objects) that module contains.

As usual, the mocked object is injected into our test method.

This time, we’ve mocked out a module rather than a function. So we examine the

call_argsnot of themock_authmodule, but of themock_auth.authenticatefunction. Because all the attributes of a mock are more mocks, that’s a mock too. You can start to see whyMockobjects are so convenient, compared to trying to build your own.

Now, instead of “unpacking” the call args, we use the

callfunction for a neater way of saying what it should have been called with-- that is, the token from the GET request. (See the following sidebar.)

What happens when we run the test? The first error is this:

$ python manage.py test accounts [...] AttributeError: <module 'accounts.views' from '/.../superlists/accounts/views.py'> does not have the attribute 'auth'

Tip

module foo does not have the attribute bar is a common first failure

in a test that uses mocks. It’s telling you that you’re trying to mock

out something that doesn’t yet exist (or isn’t yet imported) in the target

module.

Once we import django.contrib.auth, the error changes:

accounts/views.py (ch17l038)

fromdjango.contribimportauth,messages[...]

Now we get:

AssertionError: None != call(uid='abcd123')

Now it’s telling us that the view doesn’t call the auth.authenticate

function at all. Let’s fix that, but get it deliberately wrong, just to see:

accounts/views.py (ch17l039)

deflogin(request):auth.authenticate('bang!')returnredirect('/')

Bang indeed!

$ python manage.py test accounts

[...]

AssertionError: call('bang!') != call(uid='abcd123')

[...]

FAILED (failures=1)

Let’s give authenticate the arguments it expects then:

accounts/views.py (ch17l040)

deflogin(request):auth.authenticate(uid=request.GET.get('token'))returnredirect('/')

That gets us to passing tests:

$ python manage.py test accounts [...] Ran 15 tests in 0.041s OK

Using mock.return_value

Next we want to check that if the authenticate function returns a user,

we pass that into auth.login. Let’s see how that test looks:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l041)

@patch('accounts.views.auth')deftest_calls_auth_login_with_user_if_there_is_one(self,mock_auth):response=self.client.get('/accounts/login?token=abcd123')self.assertEqual(mock_auth.login.call_args,call(response.wsgi_request,mock_auth.authenticate.return_value))

We mock the

contrib.authmodule again.

This time we examine the call args for the

auth.loginfunction.

We check that it’s called with the request object that the view sees, and the “user” object that the

authenticatefunction returns. Becauseauthenticateis also mocked out, we can use its special “return_value” attribute.

When you call a mock, you get another mock. But you can also get a copy of that returned mock from the original mock that you called. Boy, it sure is hard to explain this stuff without saying “mock” a lot! Another little console illustration might help here:

>>>m=Mock()>>>thing=m()>>>thing<Mockname='mock()'id='140652722034952'>>>>m.return_value<Mockname='mock()'id='140652722034952'>>>>thing==m.return_valueTrue

In any case, what do we get from running the test?

$ python manage.py test accounts

[...]

call(response.wsgi_request, mock_auth.authenticate.return_value)

AssertionError: None != call(<WSGIRequest: GET '/accounts/login?t[...]

Sure enough, it’s telling us that we’re not calling auth.login at all

yet. Let’s try doing that. Deliberately wrong as usual first!

accounts/views.py (ch17l042)

deflogin(request):auth.authenticate(uid=request.GET.get('token'))auth.login('ack!')returnredirect('/')

Ack indeed!

TypeError: login() missing 1 required positional argument: 'user'

[...]

AssertionError: call('ack!') != call(<WSGIRequest: GET

'/accounts/login?token=[...]

Let’s fix that:

accounts/views.py (ch17l043)

deflogin(request):user=auth.authenticate(uid=request.GET.get('token'))auth.login(request,user)returnredirect('/')

Now we get this unexpected complaint:

ERROR: test_redirects_to_home_page (accounts.tests.test_views.LoginViewTest) [...] AttributeError: 'AnonymousUser' object has no attribute '_meta'

It’s because we’re still calling auth.login indiscriminately on any kind

of user, and that’s causing problems back in our original test for the

redirect, which isn’t currently mocking out auth.login. We need to add an

if (and therefore another test), and while we’re at it we’ll learn about

patching at the class level.

Patching at the Class Level

We want to add another test, with another @patch('accounts.views.auth'),

and that’s starting to get repetitive. We use the “three strikes” rule,

and we can move the patch decorator to the class level. This will have

the effect of mocking out accounts.views.auth in every single test

method in that class. That also means our original redirect test will

now also have the mock_auth variable injected:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch17l044)

@patch('accounts.views.auth')classLoginViewTest(TestCase):deftest_redirects_to_home_page(self,mock_auth):[...]deftest_calls_authenticate_with_uid_from_get_request(self,mock_auth):[...]deftest_calls_auth_login_with_user_if_there_is_one(self,mock_auth):[...]deftest_does_not_login_if_user_is_not_authenticated(self,mock_auth):mock_auth.authenticate.return_value=Noneself.client.get('/accounts/login?token=abcd123')self.assertEqual(mock_auth.login.called,False)

We move the patch to the class level…

which means we get an extra argument injected into our first test method…

And we can remove the decorators from all the other tests.

In our new test, we explicitly set the

return_valueon theauth.authenticatemock, before we call theself.client.get.

We assert that, if

authenticatereturnsNone, we should not callauth.loginat all.

That cleans up the spurious failure, and gives us a specific, expected failure to work on:

self.assertEqual(mock_auth.login.called, False) AssertionError: True != False

And we get it passing like this:

accounts/views.py (ch17l045)

deflogin(request):user=auth.authenticate(uid=request.GET.get('token'))ifuser:auth.login(request,user)returnredirect('/')

The Moment of Truth: Will the FT Pass?

I think we’re just about ready to try our functional test!

Let’s just make sure our base template shows a different nav bar for logged-in and non–logged-in users (which our FT relies on):

lists/templates/base.html (ch17l046)

<navclass="navbar navbar-default"role="navigation"><divclass="container-fluid"><aclass="navbar-brand"href="/">Superlists</a>{% if user.email %}<ulclass="nav navbar-nav navbar-right"><liclass="navbar-text">Logged in as {{ user.email }}</li><li><ahref="#">Log out</a></li></ul>{% else %}<formclass="navbar-form navbar-right"method="POST"action="{% url 'send_login_email' %}"><span>Enter email to log in:</span><inputclass="form-control"name="email"type="text"/>{% csrf_token %}</form>{% endif %}</div></nav>

And see if that…

$ python manage.py test functional_tests.test_login

Internal Server Error: /accounts/login

[...]

File "/.../superlists/accounts/views.py", line 31, in login

auth.login(request, user)

[...]

ValueError: The following fields do not exist in this model or are m2m fields:

last_login

[...]

selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate

element: Log out

Oh no! Something’s not right. But assuming you’ve kept the LOGGING

config in settings.py, you should see the explanatory traceback, as just shown. It’s saying something about a last_login field.

In my opinion this is a

bug in Django, but essentially the auth framework expects the user

model to have a last_login field. We don’t have one. But never fear!

There’s a way of handling this failure.

Let’s write a unit test that reproduces the bug first. Since it’s to do with our custom user model, as good a place to have it as any might be test_models.py:

accounts/tests/test_models.py (ch17l047)

fromdjango.testimportTestCasefromdjango.contribimportauthfromaccounts.modelsimportTokenUser=auth.get_user_model()classUserModelTest(TestCase):deftest_user_is_valid_with_email_only(self):[...]deftest_email_is_primary_key(self):[...]deftest_no_problem_with_auth_login(self):user=User.objects.create(='edith@example.com')user.backend=''request=self.client.request().wsgi_requestauth.login(request,user)# should not raise

We create a request object and a user, and then we pass them into the

auth.login function.

That will raise our error:

auth.login(request, user) # should not raise [...] ValueError: The following fields do not exist in this model or are m2m fields: last_login

The specific reason for this bug isn’t really important for the purposes of this book, but if you’re curious about what exactly is going on here, take a look through the Django source lines listed in the traceback, and have a read up of Django’s docs on signals.

The upshot is that we can fix it like this:

accounts/models.py (ch17l048)

importuuidfromdjango.contribimportauthfromdjango.dbimportmodelsauth.signals.user_logged_in.disconnect(auth.models.update_last_login)classUser(models.Model):[...]

How does our FT look now?

$ python manage.py test functional_tests.test_login [...] . --------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran 1 test in 3.282s OK

It Works in Theory! Does It Work in Practice?

Wow! Can you believe it? I scarcely can! Time for a manual look around

with runserver:

$ python manage.py runserver [...] Internal Server Error: /accounts/send_login_email Traceback (most recent call last): File "/.../superlists/accounts/views.py", line 20, in send_login_email ConnectionRefusedError: [Errno 111] Connection refused

You’ll probably get an error, like I did, when you try to run things manually. Two possible problems:

-

Firstly, we need to re-add the email configuration to settings.py.

-

Secondly, we probably need to

exportthe email password in our shell.

superlists/settings.py (ch17l049)

EMAIL_HOST='smtp.gmail.com'EMAIL_HOST_USER='obeythetestinggoat@gmail.com'EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD=os.environ.get('EMAIL_PASSWORD')EMAIL_PORT=587EMAIL_USE_TLS=True

and

$ export EMAIL_PASSWORD="sekrit" $ python manage.py runserver

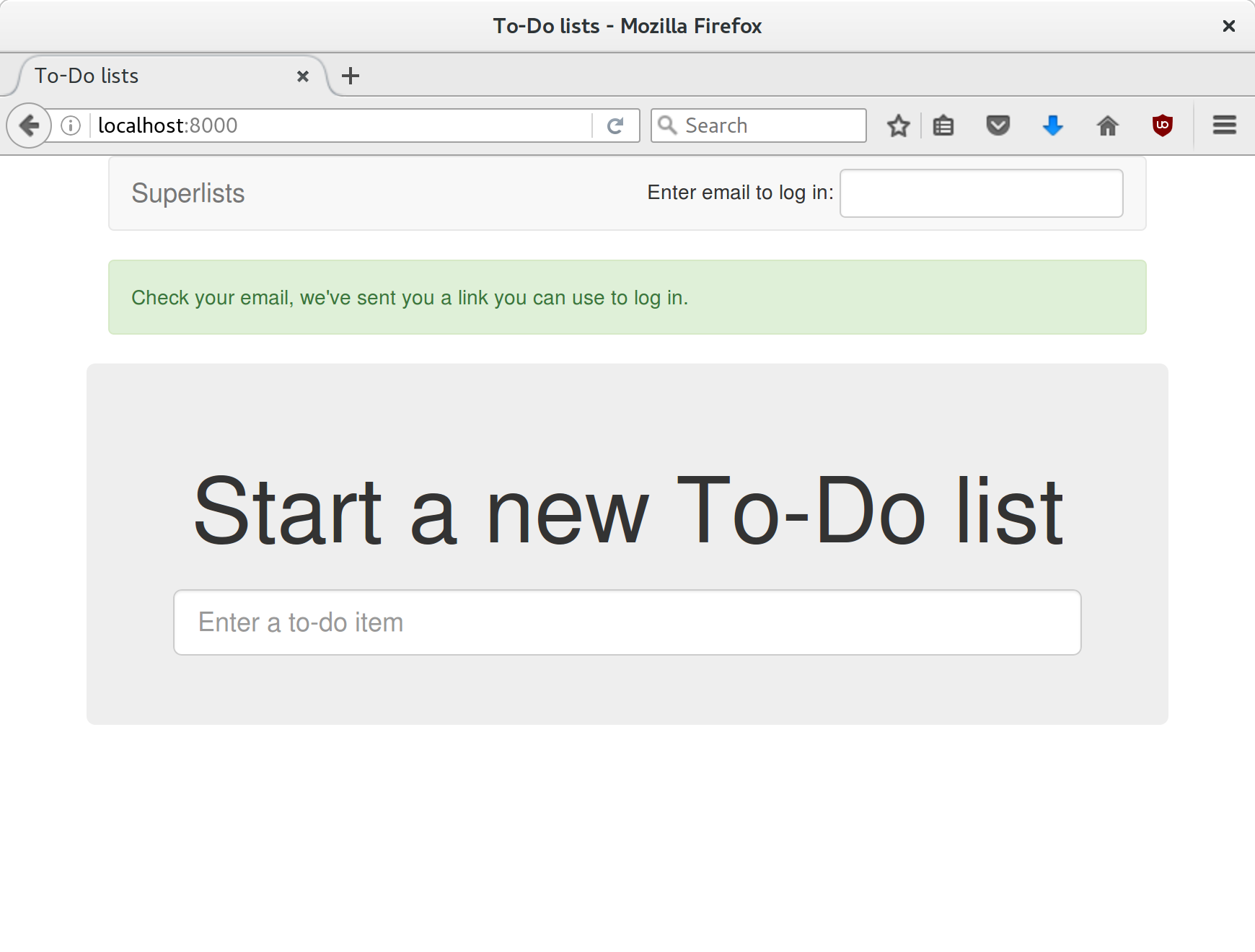

Then you should see something like Figure 19-1.

Figure 19-1. Check your email….

Woohoo!

I’ve been waiting to do a commit up until this moment, just to make sure everything works. At this point, you could make a series of separate commits—one for the login view, one for the auth backend, one for the user model, one for wiring up the template. Or you could decide that, since they’re all interrelated, and none will work without the others, you may as well just have one big commit:

$ git status $ git add . $ git diff --staged $ git commit -m "Custom passwordless auth backend + custom user model"

Finishing Off Our FT, Testing Logout

The last thing we need to do before we call it a day is to test the logout link. We extend the FT with a couple more steps:

functional_tests/test_login.py (ch17l050)

[...]# she is logged in!self.wait_for(lambda:self.browser.find_element_by_link_text('Log out'))navbar=self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.navbar')self.assertIn(TEST_EMAIL,navbar.text)# Now she logs outself.browser.find_element_by_link_text('Log out').click()# She is logged outself.wait_for(lambda:self.browser.find_element_by_name('email'))navbar=self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.navbar')self.assertNotIn(TEST_EMAIL,navbar.text)

With that, we can see that the test is failing because the logout button doesn’t work:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests.test_login [...] selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate element: [name="email"]

Implementing a logout button is actually very simple: we can use Django’s built-in logout view, which clears down the user’s session and redirects them to a page of our choice:

accounts/urls.py (ch17l051)

fromdjango.contrib.auth.viewsimportlogout[...]urlpatterns=[url(r'^send_login_email$',views.send_login_email,name='send_login_email'),url(r'^login$',views.login,name='login'),url(r'^logout$',logout,{'next_page':'/'},name='logout'),]

And in base.html, we just make the logout into a real URL link:

lists/templates/base.html (ch17l052)

<li><ahref="{% url 'logout' %}">Logout</a></li>

And that gets us a fully passing FT—indeed, a fully passing test suite:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests.test_login [...] OK $ python manage.py test [...] Ran 59 tests in 78.124s OK

Warning

We’re nowhere near a truly secure or acceptable login system here. Since this is just an example app for a book, we’ll leave it at that, but in “real life” you’d want to explore a lot more security and usability issues before calling the job done. We’re dangerously close to “rolling our own crypto” here, and relying on a more established login system would be much safer.

In the next chapter, we’ll start trying to put our login system to good use. In the meantime, do a commit and enjoy this recap:

1 I’m using the generic term “mock”, but testing enthusiasts like to distinguish other types of a general class of test tools called “Test Doubles”, including spies, fakes, and stubs. The differences don’t really matter for this book, but if you want to get into the nitty-gritty, check out this amazing wiki by Justin Searls. Warning: absolutely chock full of great testing content.

2 Yes, I know Django already mocks out emails using mail.outbox for us, but, again, let’s pretend it doesn’t. What if you were using Flask? Or what if this was an API call, not an email?

3 In Python 2, you can install it with pip install mock.

4 I’ve split the form tag across three lines so it fits nicely in the book. If you’ve not seen it before, it may look a little weird to you, but it is valid HTML. You don’t have to use it if you don’t like it though. :)