[169] The treatise De vita longa,1 difficult as it is to understand in parts, gives us some information on this point, though we have to extricate it with an effort from the arcane terminology in which it is embedded. The treatise is one of the few that were written in Latin; the style is exceedingly strange, but all the same it contains so many significant hints that it is worth investigating more closely. Adam von Bodenstein, who edited it, says in a dedicatory letter2 to Ludwig Wolfgang von Hapsberg, governor of Badenweiler, that it was “taken down from the mouth of Paracelsus and carefully revised.” The obvious inference is that the treatise is based on notes of Paracelsus’s lectures and is not an original text. As Bodenstein himself wrote fluent and easily understandable Latin, quite unlike that of the treatise, one must assume that he did not devote any particular attention to it and made no effort to put it into more intelligible form, otherwise much more of his own style would have crept in. Probably he left the lectures more or less in their original state, as is particularly apparent towards the end. It is also likely that he had no very clear understanding of what they were about, any more than had the supposed translator Oporin. This is not surprising, as the Master himself all too often lacks the necessary clarity when discussing these complicated matters. Under these circumstances it is difficult to say how much should be put down to incomprehension and how much to undisciplined thinking. Nor is the possibility of actual errors in transcription excluded.3 In our interpretation, therefore, we are on uncertain ground from the start, and much must remain conjecture. But as Paracelsus, for all his originality, was strongly influenced by alchemical thinking, a knowledge of the earlier and contemporary alchemical treatises, and of the writings of his pupils and followers, is of considerable help in interpreting some of the concepts and in filling out certain gaps. An attempt to comment on and to interpret the treatise, therefore, is not entirely hopeless, despite the admitted difficulties.

[170] The treatise is mainly concerned with the conditions under which longevity, which in Paracelsus’s opinion extends up to a thousand years or more, can be attained. In what follows I shall give chiefly the passages that relate to the secret doctrine and are of help in explaining it.4 Paracelsus starts by giving a definition of life, as follows: “Life, by Hercules, is nothing other than a certain embalsamed Mumia, which preserves the mortal body from the mortal worms and from corruption5 by means of a mixed saline solution.” Mumia was well known in the Middle Ages as a medicament, and it consisted of the pulverized parts of real Egyptian mummies, in which there was a flourishing trade. Paracelsus attributes incorruptibility to a special virtue or agent named “balsam.” This was something like a natural elixir, by means of which the body was kept alive or, if dead, incorruptible.6 By the same logic, a scorpion or venomous snake necessarily had in it an alexipharmic, i.e., an antidote, otherwise it would die of its own poison.

[171] Paracelsus goes on to discuss a great many arcane remedies, since diseases shorten life and have above all to be cured. The chief among these remedies are gold and pearls, which latter can be transformed into the quinta essentia. A peculiar potency is attributed to Cheyri,7 which fortifies the microcosmic body so much that it “must necessarily continue in its conservation through the universal anatomy of the four elements.”8 Therefore the physician should see to it that the “anatomy” (= structure) of the four elements “be contracted into the one anatomy of the microcosm, not out of the corporeal, but out of that which preserves the corporeal.” This is the balsam, which stands even higher than the quinta essentia, the thing that ordinarily holds the four elements together. It “excels even nature herself” because it is produced by a “bodily operation.”9 The idea that the art can make something higher than nature is typically alchemical. The balsam is the life principle, the spiritus mercurii, and it more or less coincides with the Paracelsan concept of the Iliaster. The latter is higher than the four elements and determines the length of life. It is therefore roughly the same as the balsam, or one could say that the balsam is the pharmacological or chemical aspect of the Iliaster.10 The Iliaster has three forms: Iliaster sanctitus,11 paratetus,12 and magnus. They are subordinate to man (“microcosmo subditi”) and can be brought “into one gamonymus.” Since Paracelsus attributes a special “vis ac potestas coniunctionis” to the Iliaster, this enigmatic “gamonymus” (γάμος = marriage, ὄνομα = name) must be interpreted as a kind of chymical wedding, in other words as an indissoluble, hermaphroditic union.13 There are as many Iliastri as there are men; that is to say in every man there is an Iliaster that holds together each individual’s peculiar combination of qualities.14 It therefore seems to be a kind of universal formative principle and principle of individuation.

[172] The Iliaster forms the starting point for the arcane preparation of longevity. “We will explain what is most needful in this process regarding the Iliaster. In the first place, the impure animate body must be purified through the separation of the elements, which is done by your meditating upon it; this consists in the confirmation of your mind beyond all bodily and mechanic work.”15 In this way a “new form is impressed” on the impure body.

[173] I have translated imaginatio here by “meditating.” In the Paracelsist tradition imaginatio is the active power of the astrum (star) or corpus coeleste sive supracoeleste (Ruland), that is, of the higher man within. Here we encounter the psychic factor in alchemy: the artifex accompanies his chemical work with a simultaneous mental operation which is performed by means of the imagination. Its purpose is to cleanse away the impure admixture and at the same time to bring about the “confirmation” of the mind. The Paracelsan neologism confirmamentum is probably not without reference to the “firmament.” During this work man is “raised up in his mind, so that he is made equal to the Enochdiani” (those who enjoy an unusually long life, like Enoch).16 Hence his “interior anatomy” must be heated to the highest degree.17 In this way the impurities are consumed and only the solid is left, “without rust.” While the artifex heats the chemical substance in the furnace he himself is morally undergoing the same fiery torment and purification.18 By projecting himself into the substance he has become unconsciously identical with it and suffers the same process. Paracelsus does not fail to point out to his reader that this fire is not the same as the fire in the furnace. This fire, he says, contains nothing more of the “Salamandrine Essence or Melusinian Ares,” but is rather a “retorta distillatio from the midst of the centre, beyond all coal fire.” Since Melusina is a watery creature, the “Melusinian Ares”19 refers to the so-called “Aquaster,”20 which stands for the watery aspect of the Iliaster, i.e., the Iliaster which animates and preserves the liquids in the body. The Iliaster is without doubt a spiritual, invisible principle although it is also something like the prima materia, which, however, in alchemical usage by no means corresponds to what we understand by matter. For the alchemists the prima materia was the humidum radicale (radical moisture),21 the water,22 the spiritus aquae,23 and vapor terrae;24 it was also called the “soul” of the substances,25 the sperma mundi,26 Adam’s tree of paradise with its many flowers, which grows on the sea,27 the round body from the centre,28 Adam and the accursed man,29 the hermaphroditic monster,30 the One and the root of itself,31 the All,32 and so on. The symbolical names of the prima materia all point to the anima mundi, Plato’s Primordial Man, the Anthropos and mystic Adam, who is described as a sphere (= wholeness), consisting of four parts (uniting different aspects in itself), hermaphroditic (beyond division by sex), and damp (i.e., psychic). This paints a picture of the self, the indescribable totality of man.

[174] The Aquaster, too, is a spiritual principle; for instance, it shows the adept the “way by which he can search out divine magic.” The adept himself is an “aquastric magician.” The “scayolic33 Aquaster” shows him the “great cause” with the help of the Trarames (ghostly spirits). Christ took his body from the celestial Aquaster, and the body of Mary was “necrocomic”34 and “aquastric.” Mary “came from the iliastric Aquaster.” There, Paracelsus emphasizes, she stood on the moon (the moon is always related to water). Christ was born in the celestial Aquaster. In the human skull there is an “aquastric fissure,” in men on the forehead, in women at the back of the head. Through this fissure women are liable to be invaded in their “cagastric” Aquaster by a crowd of diabolical spirits; but men, through their fissure, give birth, “not cagastrically but necrocomically, to the necrocomic Animam vel spiritum vitae microcosmi, the iliastric spirit of life in the heart.” In the “centre of the heart dwells the true soul, the breath of God.”35

[175] From these quotations it is easy to see what the Aquaster means. Whereas the Iliaster seems to be a dynamic spiritual principle, capable of both good and evil, the Aquaster, because of its watery nature, is more a “psychic” principle with quasimaterial attributes (since the bodies of Christ and Mary partook of it). But it functions psychically as a “necrocomic” (i.e., telepathic) agent related to the spiritual world, and as the birthplace of the spiritus vitae. Of all the Paracelsan concepts, therefore, the Aquaster comes closest to the modern concept of the unconscious. So we can see why Paracelsus personifies it as the homunculus and describes the soul as the celestial Aquaster. Like a true alchemist, he thought of the Aquaster and Iliaster as extending both upwards and downwards: they assume a spiritual or heavenly form as well as a quasi-material or earthly one. This is in keeping with the axiom from “Tabula smaragdina”: “What is below is like what is above, that the miracle of the one thing may be accomplished.” This one thing is the lapis or filius philosophorum.36 As the definitions and names of the prima materia make abundantly plain, matter in alchemy is material and spiritual, and spirit spiritual and material. Only, in the first case matter is cruda, confusa, grossa, crassa, densa, and in the second it is subtilis. Such, too, is the opinion of Paracelsus.

[176] Rather superficially, Adam von Bodenstein conceives “Ares” to be the “prime nature of things, determining their form and species.”37 Ruland lumps it together with the Iliaster and Archeus. But whereas the Iliaster is the hypostasis of being in general (“generis generalissimi substantia”), Archeus is given the role of a “dispenser of nature” (naturae dispensator) and “initiator.” Ares, however, is the “assigner, who extends the peculiar nature to each species, and gives individual form.”38 It can therefore be taken as the principle of individuation in the strict sense. It proceeds from the supracelestial bodies, for “such is the property and nature of supracelestial bodies that they straightway produce out of nothing a corporeal imagination [imaginationem corporalem], so as to be thought a solid body. Of this kind is Ares, so that when one thinks of a wolf, a wolf appears.39 This world is like the creatures composed of the four elements. From the elements arise things which are in no way like their origins, but nonetheless Ares bears them all in himself.”40

[177] Ares, accordingly, is an intuitive concept for a preconscious, creative, and formative principle which is capable of giving life to individual creatures. It is thus a more specific principle of individuation than the Iliaster, and as such it plays an important role in the purification of the natural man by fire and his transformation into an “Enochdianus.” The fire he is heated with is, as we have seen, no ordinary fire, since it does not contain either the “Melusinian Ares” or the “Salamandrine Essence.” The salamander symbolizes the fire of the alchemists. It is itself of the nature of fire, a fiery essence. According to Paracelsus, Salamandrini and Saldini are men or spirits of fire, fiery beings. It is an old tradition that, because they have proved their incorruptibility in the fire, such creatures enjoy a particularly long life. The salamander is also the “incombustible sulphur”—another name for the arcane substance from which the lapis or filius is produced. The fire for heating the artifex contains nothing more of the nature of the salamander, which is an immature, transitional form of the filius, that incorruptible being whose symbols indicate the self.

[178] Paracelsus endows Ares with the attribute “Melusinian.” Since Melusina undoubtedly belongs to the watery realm, the realm of the nymphs, this attribute imports a watery character into the concept of Ares, which in itself is spiritual. Ares is thus brought into relationship with the lower, denser region and is intimately connected with the body. As a result, Ares becomes so like the Aquaster that it is scarcely possible to distinguish them conceptually. It is characteristic of Paracelsan thinking, and of alchemy in general, that there are no clear-cut concepts, so that one concept can take the place of another ad infinitum. At the same time every concept behaves hypostatically, as though it were a substance that could not at the same time be another substance. This typical primitive phenomenon is found also in Indian philosophy, which swarms with hypostases. Examples of this are the myths of the gods, which, as in Greek and Egyptian mythology, make utterly contradictory statements about the same god. Despite their contradictions, however, the myths continue to exist side by side without disturbing one another.

[179] As we shall meet with Melusina several times more in the course of our interpretation, we must examine more closely the nature of this fabulous creature, and in particular the role she plays in Paracelsus. As we know, she belongs to the realm of the Aquaster, and is a water-nymph with the tail of a fish or snake. In the original old French legend she appears as “mère Lusine,” the ancestress of the counts of Lusignan. When her husband once surprised her in her fish-tail, which she had to wear only on Saturdays, her secret was out and she was forced to disappear again into the watery realm. She reappeared only from time to time, as a presage of disaster.

[180] Melusina comes into the same category as the nymphs and sirens who dwell in the “Nymphidida,” the watery realm.41 In the treatise “De sanguine,”42 the nymph is specified as a Schröttli, ‘nightmare.’ Melusines, on the other hand, dwell in the blood.43 Paracelsus tells us in “De pygmaeis”44 that Melusina was originally a nymph who was seduced by Beelzebub into practising witchcraft. She was descended from the whale in whose belly the prophet Jonah beheld great mysteries. This derivation is very important: the birthplace of Melusina is the womb of the mysteries, obviously what we today would call the unconscious. Melusines have no genitals,45 a fact that characterizes them as paradisal beings, since Adam and Eve in paradise had no genitals either.46’ Moreover paradise was then beneath the water “and still is.”47 When the devil glided into the tree of paradise the tree was “saddened,” and Eve was seduced by the “infernal basilisk.”48 Adam and Eve “fell for” the serpent and became “monstrous,” that is, as a result of their slip-up with the snake they acquired genitals.49 But the Melusines remained in the paradisal state as water creatures and went on living in the human blood. Since blood is a primitive symbol for the soul,50 Melusina can be interpreted as a spirit, or at any rate as some kind of psychic phenomenon. Gerard Dorn confirms this in his commentary on De vita longa, where he says that Melusina is a “vision appearing in the mind.”51 For anyone familiar with the subliminal processes of psychic transformation, Melusina is clearly an anima figure. She appears as a variant of the mercurial serpent, which was sometimes represented in the form of a snake-woman52 by way of expressing the monstrous, double nature of Mercurius. The redemption of this monstrosity was depicted as the assumption and coronation of the Virgin Mary.53

[181] It is not my intention to enter more closely into the relations between the Paracelsan Melusines and the mercurial serpent. I only wish to point out the alchemical prototypes that may have had an influence on Paracelsus, and to suggest that the longing of Melusina for a soul and for redemption has a parallel in that kingly substance which is hidden in the sea and cries out for deliverance. Of this filius regius Michael Maier says:54 “He lives and calls from the depths:55 Who shall deliver me from the waters and lead me to dry land? Even though this cry be heard of many, yet none takes it upon himself, moved by pity, to seek the king. For who, they say, will plunge into the waters? Who will imperil his life by taking away the peril of another? Only a few believe his lament, and think rather that they hear the crashing and roaring of Scylla and Charybdis. Therefore they remain sitting indolently at home, and give no thought to the kingly treasure, nor to their own salvation.”

[182] We know that Maier can have had no access to the Philosophumena of Hippolytus, long believed lost, and yet it might well have served him as a model for the king’s lament. Treating of the mysteries of the Naassenes, Hippolytus says: “But what that form is which comes down from above, from the Uncharacterized [ἀχαρακτηρἰστου], no man knows. It is found in earthly clay, and yet none recognize it. But that is the god who dwells in the great flood.58 In the Psalter he calls and cries out from many waters.57 The many waters, they say, are the multitude of mortal men, whence he calls and cries aloud to the uncharacterized Man:58 Save mine Only-Begotten59 from the lions.”60 And he receives the reply [Isaiah 43 : 1ff.]: “And now thus saith the Lord that created thee, O Jacob, and formed thee, O Israel: Fear not, for I have redeemed thee, and called thee by thy name. Thou art mine. When thou shalt pass through the waters, I will be with thee, and the rivers shall not cover thee. When thou shalt walk through the fire, thou shalt not be burnt, and the flames shall not burn in thee.” Hippolytus goes on to quote Psalm 23 : 7ff., (DV), referring it to the ascent (ἄνοδος) or regeneration (ἀναγέννησις) of Adam: “Lift up your gates, O ye princes, and be ye lifted up, O eternal gates, and the King of Glory shall enter in. Who is this King of Glory? The Lord who is strong and mighty, the Lord mighty in battle. . . . But who, say the Naassenes, is this King of Glory? A worm and no man, the reproach of men and the outcast of the people.”61

[183] It is not difficult to see what Michael Maier means. For him the filius regius or Rex marinus, as is evident from a passage in the text not quoted here, means antimony,62 though in his usage it has only the name in common with the chemical element. In reality it is the secret transformative substance, which fell from the highest place into the darkest depths of matter where it awaits deliverance. But no one will plunge into these depths in order, by his own transformation in the darkness and by the torment of fire, to rescue his king. They cannot hear the voice of the king and think it is the chaotic roar of destruction. The sea (mare nostrum) of the alchemists is their own darkness, the unconscious. In his way, Epiphanius63 correctly interpreted the “mire of the deep” (limus profundi) as “matter born of the mind, smutty reflections and muddy thoughts of sin.” Therefore David in his affliction had said (Psalm 68 : 3, DV): “I stick fast in the mire of the deep.” For the Church Father these dark depths could only be evil itself, and if a king got stuck in them it was on account of his own sinfulness. The alchemists took a more optimistic view: the dark background of the soul contains not only evil but a king in need of, and capable of, redemption, of whom the Rosarium says: “At the end of the work the king will go forth for thee, crowned with his diadem, radiant as the sun, shining like the carbuncle . . . constant in the fire.”64 And of the worthless prima materia they say: “Despise not the ash, for it is the diadem of thy heart, and the ash of things that endure.”65

[184] These quotations give one an idea of the mystic aura that surrounded the figure of the filius regius, and I do not think it superfluous to have drawn attention to that distant period when the central ideas of philosophical alchemy were being freely discussed by the Gnostics. Hippolytus gives us perhaps the most complete insight into their analogical thinking, which is akin to that of the alchemists. Anyone who came into contact with alchemy during the first half of the sixteenth century could not fail to feel the fascination of these Gnostic ideas. Although Maier lived and wrote more than seventy years after Paracelsus, and we have no reason to suppose that Paracelsus was acquainted with the heresiologists, his knowledge of the alchemical treatises, and particularly of Hermes [Fig. B6] which he so often quotes, would have sufficed to impress upon him the figure of the filius regius and also that of the much lauded Mater Natura—a figure not entirely in accord with the views of Christianity. Thus the “Tractatus aureus Hermetis” says: “O mightiest nature of the natures, who containest and separatest the midmost of the natures, who comest with the light and art born with the light, who hast given birth to the misty darkness, who art the mother of all beings!”66 This invocation echoes the classical feeling for nature, and its style is reminiscent of the oldest alchemical treatises, such as those of pseudo-Democritus, and of the Greek Magic Papyri. In this same treatise we encounter the Rex coronatus and filius noster rex genitus, of whom it is said: “For the son is a blessing and possesses wisdom. Come hither, ye sons of the wise, and let us be glad and rejoice, for death is overcome, and the son reigns; he is clothed with the red garment, and the purple [chermes] is put on.” He lives from “our fire,” and nature “nourishes him who shall endure for ever” with a “small fire.” When the son is brought to life by the opus, he becomes a “warrior fire” or a “fighter of fire.”67

[185] After this discussion of some of the basic concepts of alchemy, let us come back to the Paracelsan process of transforming the Iliaster. Paracelsus calls this process a retorta distillatio. The purpose of distillation in alchemy was to extract the volatile substance, or spirit, from the impure body. This process was a psychic as well as a physical experience. The retorta distillatio is not a known technical term, but presumably it meant a distillation that was in some way turned back upon itself. It might have taken place in the vessel called the Pelican [Fig. B7], where the distillate runs back into the belly of the retort. This was the “circulatory distillation,” much favoured by the alchemists. By means of the “thousandfold distillation” they hoped to achieve a particularly “refined” result.68 It is not unlikely that Paracelsus had something like this in mind, for his aim was to purify the human body to such a degree that it would finally unite with the maior homo, the inner spiritual man, and partake of his longevity. As we have remarked, this was not an ordinary chemical operation, it was essentially a psychological procedure. The fire to be used was a symbolical fire, and the distillation had to start “from the midst of the centre” (ex medio centri).

[186] The accentuation of the centre is again a fundamental idea in alchemy. According to Michael Maier, the centre contains the “indivisible point,” which is simple, indestructible, and eternal. Its physical counterpart is gold, which is therefore a symbol of eternity.69 In Christianos the centre is compared to paradise and its four rivers. These symbolize the philosophical fluids (ὑγρά), which are emanations from the centre.70 “In the centre of the earth the seven planets took root, and left their virtues there, wherefore in the earth is a germinating water,” says Aurora consurgens.71 Benedictus Figulus72 writes:

Visit the centre of the earth,

There you will find the global fire.

Rectify it of all dirt,

Drive it out with love and ire. . . .

He calls this centre the “house of fire” or “Enoch,” obviously borrowing the latter term from Paracelsus. Dorn says that nothing is more like God than the centre, for it occupies no space, and cannot be grasped, seen, or measured. Such, too, is the nature of God and the spirits. Therefore the centre is “an infinite abyss of mysteries.”73 The fire that originates in the centre carries everything upward, but when it cools everything falls back again to the centre. “The physiochemists call this movement circular, and they imitate it in their operations.” At the moment of culmination, just before the descent, the elements “conceive the male seeds of the stars,” which enter into the elemental matrices (i.e., the non-sublimated elements) during the descent. Thus all created things have four fathers and four mothers. The conception of the seeds results from the “influxum et impressionem” of Sol and Luna, who thus function as nature gods, though Dorn does not say this quite as clearly.74

[187] The creation of the elements and their ascent to heaven through the force of the fire serve as a model for the spagyric process. The lower waters, cleansed of their darkness, must be separated from the celestial waters by a carefully regulated fire. “In the end it will come to pass that this earthly, spagyric foetus clothes itself with heavenly nature by its ascent, and then by its descent visibly puts on the nature of the centre of the earth, but nonetheless the nature of the heavenly centre which it acquired by the ascent is secretly preserved.”75 The spagyric birth (spagirica foetura) is nothing other than the filius philosophorum, the inner, eternal man in the shell of the outer, mortal man. The filius is not only a panacea for all bodily defects, it also conquers the “subtle and spiritual sickness in the human mind.” “For in the One,” says Dorn,76 “is the One and yet not the One; it is simple and consists of the number four. When this is purified by the fire in the sun,77 the pure water78 comes forth, and, having returned to simplicity,79 it [the quaternity as unity] will show the adept the fulfilment of the mysteries. This is the centre of the natural wisdom, whose circumference, closed in itself, forms a circle: an immeasurable order reaching to infinity.” “Here is the number four, within whose bounds the number three, together with the number two combined into One, fulfils all things, which it does in miraculous wise.” In these relations between four, three, two, and one is found, says Dorn, the “culmination of all knowledge and of the mystic art, and the infallible midpoint of the centre (infallibile medii centrum).”80 The One is the midpoint of the circle, the centre of the triad, and it is also the “novenary foetus” (foetus novenarius), i.e., it is as the number nine to the ogdoad, or as the quintessence to the quaternity.31

[188] The midpoint of the centre is fire. On it is modelled the simplest and most perfect form, which is the circle. The point is most akin to the nature of light,82 and light is a simulacrum Dei.83 Just as the firmament was created in the midst of the waters above and below the heavens, so in man there is a shining body, the radical moisture, which comes from the sphere of the heavenly waters.84 This body is the “sidereal balsam,” which maintains the animal heat. The spirit of the supracelestial waters has its seat in the brain, where it controls the sense organs. In the microcosm the balsam dwells in the heart,85 like the sun in the macrocosm. The shining body is the corpus astrale, the “firmament” or “star” in man. Like the sun in the heavens, the balsam in the heart is a fiery, radiant centre. We meet this solar point in the Turba,86 where it signifies the “germ of the egg, which is in the yolk, and that germ is set in motion by the hen’s warmth.” The “Consilium coniugii” says that in the egg are the four elements and the “red sun-point in the centre, and this is the young chick.”87 Mylius interprets this chick as the bird of Hermes,88 which is another synonym for the mercurial serpent.

[189] From this context we can see that the retorta distillatio ex medio centri results in the activation and development of a psychic centre, a concept that coincides psychologically with that of the self.

[190] At the end of the process, says Paracelsus, a “physical lightning” will appear, the “lightning of Saturn” will separate from the lightning of Sol, and what appears in this lightning pertains “to longevity, to that undoubtedly great Iliaster.”89 This process does not take anything away from the body’s weight but only from its “turbulence,” and that “by virtue of the translucent colours.”80 “Tranquillity of mind”91 as a goal of the opus is stressed also by other alchemists. Paracelsus has nothing good to say about the body. It is “bad and putrid.” When it is alive, it lives only from the “Mumia.” Its “continual endeavour” is to rot and turn back into filth. By means of the Mumia the “peregrinus microcosmus” (wandering microcosm) controls the physical body, and for this the arcana are needed.92 Here Paracelsus lays particular stress on Thereniabin93 and Nostoch94 (as before on Cheyri) and on the “tremendous powers” of Melissa. Melissa is singled out for special honour because in ancient medicine it was considered to be a means of inducing happiness, and was used as a remedy for melancholia and for purging the body of “black, burnt-out blood.”95 It unites in itself the powers of the “supracelestial coniunctio,” and that is “Iloch, which comes from the true Aniadus.” As Paracelsus had spoken just before of Nostoch, the Iliaster has changed under his eyes into Iloch. The Aniadus that now makes its appearance constitutes the essence of Iloch, i.e., of the coniunctio. But to what does the coniunctio refer? Before this Paracelsus had been speaking of a separation of Saturn and Sol. Saturn is the cold, dark, heavy, impure element, Sol is the opposite. When this separation is completed and the body has been purified by Melissa and freed from Saturnine melancholy, then the coniunctio can take place with the long-living inner, or astral, man,96 and from this conjunction arises the “Enochdianus.” Iloch or Aniadus appears to be something like the virtue or power of the everlasting man. This “Magnale” comes about by the “exaltation of both worlds,” and “in the true May, when the exaltations of Aniada begin, these should be gathered.” Here again Paracelsus outdoes himself in obscurity, but this much at least is evident, that Aniadus denotes a springtime condition, the “efficacity of things,” as Dorn defines it.

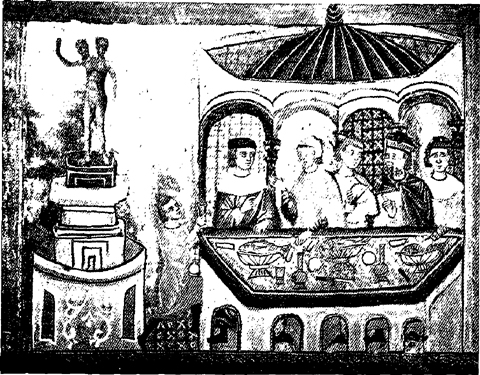

A fish meal, with accompanying statue of the hermaphrodite. Though the picture is undoubtedly secular, it contains echoes of early Christian motifs. The significance of the hermaphrodite in this context is unknown to me. British Museum. MS. Add. 15268 (13th cent.)

The filius or rex in the form of a hermaphrodite. The axiom of Maria is represented by 1 + 3 snakes: the filius, as mediator, unites the one with the three. Characteristically, he has bat’s wings. To the right is the Pelican, symbol of the distillatio circulatoria; to the left, the arbor philosophica with golden flowers; underneath, the chthonic triad as a three-headed serpent. From Rosarium philosophorum (1550), fol. X, iiiv

The Rebis: from “Book of the Holy Trinity and Description of the Secret of the Transmutation of Metals” (1420), in the Codex Germanicus 598 (Staatsbibliothek, Munich), fol. 105v. The illustration may have served as a model for the hermaphrodite in the Rosarium (pl. B2)

Melusina as the (aqua permanens, opening the side of the filius (an allegory of Christ) with the lance of Longinus. The figure in the middle is Eve (earth), who is reunited with Adam (Christ) in the coniunctio. From their union is born the hermaphrodite, the incarnate Primordial Man. To the right is the athanor (furnace) with the vessel in the centre, from which the lapis (hermaphrodite) will arise. The vessels on either side contain Sol and Luna. Woodcut from Reusner’s Pandora: Das ist, die edelst Gab Gottes, oder der werde und heilsame Stein der Weysen (Basel. 1588), p. 249

The anima as Melusina, embracing a man rising out of the sea (= unconscious): a coniunetio animae cum corpore. The gnomes are the planetary spirits in the form of paredroi (familiars). British Museum. MS. Sloane 5025, a variant of the Ripley Scrowle (1588)

The King’s Son (filius regis) and the mystagogue Hermes on a mountain, an obvious allusion to the Temptation (Luke, ch. 4). The accompanying text says: “Another mountain of India lies in the vessel, which the Spirit and Soul, as son and guide, have together ascended.” The two are called spirit and soul because they represent volatile substances which rise up during the heating of the prima materia. From Lambspringk, “De lapide philosophico,” fig. XII. in Musaeum hermeticum (Frankfurt a. M., 1678), p. 365

Picture of the Pelican. the vessel in which the circulatory distillation takes plate. Page from Rhenanus, Solis e puteo emergentis sive dissertationis chymotechnicae libri tres (Frankfurt a. M., 1613)

[191] We meet this motif in one of the earliest Greek texts, entitled the “Instruction of Cleopatra by the Archpriest Komarios,”97 where Ostanes98 and his companions say to Cleopatra:

Make known to us how the highest descends to the lowest, and the lowest ascends to the highest, and the midmost draws near to the lowest and the highest, so that they are made one with it;99 how the blessed waters come down from above to awaken the dead, who lie round about in the midst of Hades, chained in the darkness; how the elixir of life comes to them and awakens them, rousing them out of their sleep. . . .

[192] Cleopatra answers:

When the waters come in, they awaken the bodies and the spirits, which are imprisoned and powerless. . . . Gradually they bestir themselves, rise up, and clothe themselves in bright colours,100 glorious as the flowers in spring. The spring is glad and rejoices in the blossoming ripeness they have put on.

[193] Ruland defines Aniada101 as “fruits and powers of paradise and heaven; they are also the Christian Sacraments . . . those things which by thought, judgment, and imagination promote longevity in us.”102 They seem therefore to be powers that confer everlasting life, an even more potent ϕάρμακον ἀθανασίας than Cheyri, Thereniabin, Nostoch, and Melissa. They correspond to the blessed waters of Komarios and also, apparently, to the Communion substances. In the spring all the forces of life are in a state of festive exaltation, and the opus alchymicum should also begin in the spring103 (already in the month of Aries, whose ruler is Mars). At that time the Aniada should be “gathered,” as though they were healing herbs. There is an ambiguity here: it could also mean the gathering together of all the psychic powers for the great transformation. The hierosgamos of Poliphilo likewise takes place in the month of May,104 that is, the union with the soul, the latter embodying the world of the gods. At this marriage the human and the divine are made one; it is an “exaltation of both worlds,” as Paracelsus says. He adds significantly: “And the exaltations of the nettles burn too, and the colour of the little flame105 sparkles and shines.” Nettles were used for medicinal purposes (the preparation of nettle water), and were collected in May because they sting most strongly when they are young. The nettle was therefore a symbol of youth, which is “most prone to the flames of lust.”106 The allusion to the stinging nettle and the flammula is a discreet reminder that not only Mary but Venus, too, reigns in May. In the next sentence Paracelsus remarks that this power can be “changed into something else.” There are exaltations, he says, far more powerful than the nettle, namely the Aniada, and these are found not in the matrices, that is, in the physical elements, but in the heavenly ones. The Ideus would be nothing if it had not brought forth greater things. For it had made another May, when heavenly flowers bloomed. At this time Anachmus107 must be extracted and preserved, even as “musk rests in the pomander108 and the virtue of gold in laudanum.”109 One can enjoy longevity only when one has gathered the powers of Anachmus. To my knowledge, there is no way of distinguishing Anachmus from Aniadus.