She is all beauty—

this woman nude and terrible and black,

who tells the name of God

on the skulls of the dead,

who creates the bloodshed on which demons fatten,

who slays rejoicing and repents not,

and blesses him only that lies crushed beneath Her feet.

Her mass of black hair

flows behind Her like the wind,

or like time “the drift and passage of things.”

She is blue almost to blackness, like a mighty shadow,

and bare like the dread realities of life and death1

The scene for true Kali worship takes place in a cremation ground where the air is smoke-laden and little specks of ash from burning funeral pyres fall on white, sun-dried bones scattered about and on fragments of flesh, gnawed and pecked at by carrion beasts and large black birds. A frightful place for most, but a favorite one for the “heroic” Mother worshipper who has burnt away all worldly desires and seeks nothing but union with her. This kind of devotee fears nothing and knows no aversion.

But prone to human emotions, the majority of people are terrified by Kali's awe-inspiring grandeur, back-lit by the fires in the cremation ground. They would much rather worship her in a less threatening place, where stark reality is a symbol rather than the harsh truth. So they flock to temples, worship Kali at roadside shrines or in their own homes. They pray to the Divine Mother to grant them the boon of a child, money to feed the mouths of a hungry family, to grant them devotion and liberation from an existence in misery. “Ma, Ma, Ma go Ma; daya karun; kripa karun.” Mother, oh Mother, give me your grace, give me your compassion.

The beauty of the Dakshineswar Kali Temple is far removed from the dreary sight of an active cremation ground. And although the Goddess in this temple is the same Ma Kali as the feared one in the cremation ground, she is regarded as benign—a protectress rather than a destroyer.

How does the Hindu determine whether an image of Kali is benign or fearful? While someone unfamiliar with Shakti worship may perceive all Kali images as equally terrible without making the slightest distinction between them, the Hindu distinguishes a benign (dakshina2) from a fearful (smashan) Kali by the position of her feet. If Kali steps out with her right foot and holds the sword in her left hand, she is a Dakshina Kali. And if she steps out with her left foot and holds the sword in her right hand, she is the terrible form of the Mother, the Smashan Kali of the cremation ground. See figure 10.

Figure 10. Shiva never takes his eyes off Kali standing over his heart on his chest.

Now the question arises, why would anyone want to worship the terrible Mother of the cremation ground? According to Tantrics,3 one's spiritual disciplines practiced in a cremation ground bring success quickly. Sitting next to corpses and other images of death, one is able to transcend the “pair of opposites” (i.e., good-bad, love-hate, etc.) much faster than another who blocks out the unpleasant aspects of life. The cremation ground's ghastly images arouse instant renunciation in the mind and help the Tantric to get rid of attachment for the body.

Actually, to overcome one's attachment is not as difficult as mastering one's aversions. With a bit of discipline and willpower most people can renounce their attractions and desires, but only a rare few can ever overcome their aversions. To conquer both and thereby achieve same-sighted-ness, Tantrics practice the most extreme esoteric sadhanas. Some of their more gruesome methods include the tasting of excreta and the eating of flesh from a burning corpse.

One of the first things to occur when one tries to understand Tantra, is one's realization of how much Western views on life differ from Indian thought on the subject—in general. In India, the goal of life is God, and the person who has achieved realization of God is the most highly regarded. Kings, queens, and prime ministers bow down to such a person. But in the West, people measure the success of a person's life by his or her worldly achievements. The richest and most famous people are regarded most highly by the rest of society. This fundamental difference in attitude toward the goal of one's life between the West and East has often caused an unfortunate communication gap.

Kali is perhaps one of the most misunderstood forms of God. The ordinary Western mind perceives Kali as hideous and absurd, forgetting that some of the symbols of Western faiths have the same effect on the Hindu. While Christians believe in a God that is all good and a devil that is all bad, Hindus believe in only one Universal Power which is beyond good and bad. To explain this concept, they give the example of fire. The same fire that cooks one's food can burn down one's house. Still, can one call fire good or bad?

Kali is the full picture of the Universal Power. She is Mother, the Benign, and Mother, the Terrible. She creates and nourishes and she kills and destroys. By Her magic we see good and bad, but in reality there is neither. This whole world and all we see is the play of Maya, the veiling power of the Divine Mother. God is neither good nor bad, nor both. God is beyond the pair of opposites which constitute this relative existence.

The Tantras mention over thirty forms of Kali. Sri Ramakrishna often spoke about Kali's different forms. He said:

The Divine Mother is known as Maha Kali, Nitya Kali, Smashana Kali, Raksha Kali, and Shyama Kali. Maha Kali and Nitya Kali are mentioned in the Tantra philosophy. When there were neither the creation, nor the sun, the moon, the planets, and the earth, and when darkness was enveloped in darkness, then the Mother, the Formless One, Maha Kali, the Great Power, was one with Maha Kala, the Absolute.

Shyama Kali has a somewhat tender aspect and is worshipped in the Hindu households. She is the dispenser of boons and the dispeller of fear. People worship Raksha Kali, the Protectress, in times of epidemic, famine, earthquake, drought, and flood. Smashana Kali is the embodiment of the power of destruction. She resides in the cremation ground, surrounded by corpses, jackals and terrible female spirits. From her mouth flows a stream of blood, from her neck hangs a garland of human heads, and around her waist is a girdle made of human arms.4

Tantrics worship Siddha Kali to attain perfection; Phalaharini Kali to destroy the results of their actions; Nitya Kali, the eternal Kali, to take away their disease, grief, and suffering, and to give them perfection and illumination. There are so many forms of Kali. In fact, each district, town, and village in Bengal seems to have its very own Kali, famous for a particular miracle or incident.

Even robbers and thieves have their own Kali. Not so many years ago, robbers lived in Indian woods who had the habit of worshipping Dakait Kali5 before they went to rob people on highways and in villages. Some of these old Kali images have survived time and are still being worshipped, though for other reasons than originally intended. For instance, a famous old Dakait Kali temple in South Calcutta draws pious pilgrims from all over Bengal.

The name: Kali comes from the word “kala,” or time. She is the power of time which devours all. See figure 11 on page 42.

The setting: A power that destroys should be depicted in terms of awe-inspiring terror. Kali is found in the cremation ground amid dead bodies. She is standing in a challenging posture on the prostrate body of her husband Shiva. Kali cannot exist without him, and Shiva cannot reveal himself without her. She is the manifestation of Shiva's power, energy.

Complexion: While Shiva's complexion is pure white, Kali is the color of the darkest night—a deep bluish black. As the limitless Void, Kali has swallowed up everything without a trace. Hence she is black.

Hair: Her luxuriant hair is dishevelled and, thereby, symbolizes Kali's boundless freedom. Another interpretation says that each hair is a jiva (individual soul), and all souls have their roots in Kali.

Figure 11. Smashan Kali, with Her left foot forward, dances Her dance of destruction. The Holy Mother, Sri Ramakrishna's wife, worshipped this image of Kali. This picture is still being worshipped in Holy Mother's room at the Udbodhan Office, Calcutta.

Eyes: She has three eyes; the third one stands for wisdom.

Tongue: Her tongue is protruding, a gesture of coyness—because she unwittingly stepped on the body of her husband Shiva. A more philosophical interpretation: Kali's tongue, symbolizing rajas (the color red, activity), is held by her teeth, symbolizing sattva (the color white, spirituality).

Arms: Kali has four arms. The posture of her right arms promises fearlessness and boons while her left arms hold a bloody sword and a freshly severed, bleeding human head. Looking at Kali's right, we see good, and looking at her left, we see bad.

Dress: Kali is naked (clad in space) except for a girdle of human arms cut off at the elbow and a garland of fifty skulls. The arms represent the capacity for work, and Kali wears all work (action), potential work, and the results thereof around her waist. The fifty skulls that make up her garland represent the fifty letters of the alphabet, the manifest state of sound from which all creation evolved.

One should not jump to the conclusion that Kali represents only the destructive aspect of God's power. What exists when time is transcended, the eternal night of limitless peace and joy, is also called Kali (Maharatri). And it is she who prods Shiva Mahadeva into the next cycle of creation. In short, she is the power of God in all His aspects.6

The image of Kali in Dakshineswar has the name “Bhavatarini”—Mother, who is the Savior of the World. Although everybody calls her by this name now, nobody knows who gave it to her and when. Rani Rasmani, the builder of the temple, signed a Deed of Trust in 1861 in which Kali's name was recorded as “Sri Sri Jagadiswari Mahakali.” It is possible that Sri Ramakrishna gave her the name “Bhavatarini” at a later time; though, such an incident was never recorded by his biographers.

They say that this Mother Kali fulfills all the desires of her children, be they material wealth or spiritual liberation. If people pray to her earnestly, the Divine Mother Kali cannot withhold anything from them. She gave all knowledge and all power to Sri Ramakrishna. As he tells in his own words:

I wept before the Mother and prayed. “O Mother, please tell me, please reveal to me, what the yogis have realized through yoga and the jnanis through discrimination.” And the Mother has revealed everything to me. She reveals everything if the devotee cries to Her with a yearning heart. She has shown me everything that is in the Vedas, the Vedanta, the Puranas, and the Tantra.”7

When one stands inside Kali's shrine in Dakshineswar, it is not hard to picture Sri Ramakrishna sitting cross-legged on the floor, communing intimately with the Divine Mother. Then one suddenly becomes aware that one stands on the same floor, sees the same altar and the same image that he worshipped. And then one feels overwhelmed by a timeless proximity of a certain sweetness that seizes one's heart.

In comparison to the grand size of the entire Kali temple, Mother's inner shrine is rather small and measures only 15 × 15 feet. The sanctum has blue-tiled walls which bounce off a strong electric light that shines from the ceiling. Standing amid this harsh brilliance, the basalt image of Kali casts no shadows—for they say, God casts no shadows.

Nothing one sees reminds a Western seeker of the places one associates with religion. There is none of the sterile cleanliness of a Western church, no starched robes of priests, and certainly no hushed silence. Instead one sees a sanctum which could be termed neither dirty nor clean. One best calls it active with life. Its animate presence so completely fills the moment in one's mind that it is hard to think of the past, future, or anything else.

Priests in white dhotis8 and panjabis9 move busily about. The pujari10 has climbed up on the steps to the right of the altar and is fastening a lotus onto Ma Kali's right foot. His upper body is bare, and the sacred thread, which all male Brahmins are required to wear, is visible across his shoulder and back. He has bushy black hair and his upper arms and chest bear red sandalwood markings.

The loud, high-pitched voice of an elderly woman echoes within the shrine. Dressed in a white sari, the woman leans over the gate at the front entrance as far as possible, stretching both hands toward Kali. She cries and prays loudly to Ma Kali without a trace of restraint. As far as she is concerned, nothing can hold back her anguished spirit from being heard by the Divine Mother Kali.

The sanctum's marble floor is stained with vermillion, and red hibiscus flowers that have dropped from priests' hands lie here and there. Also strewn about are little iron bracelets, coins and incense sticks—all items thrown from the outside toward Ma Kali by eager devotees. When the floor space gets too cluttered, a servant comes around, picks up the money, and with a soft broom sweeps all else into the right corner of the sanctum where a small mountain of flowers has already accumulated.

Figure 12. The inner shrine of Kali in Dakshineswar. It is the same shrine in which Sri Ramakrishna so fervently loved and worshipped God, the Divine Mother. The structure of the shrine is made of silver and so is the lotus on which the image stands. The shrine sits atop an altar, called the bedi, which basically consists of a couple of wide steps. Today, pictures of Sri Ramakrishna and Sri Sarada Ma have been added to the images of Gods and Goddesses residing on the altar. (Photo by Gandhi Roy.)

The smells of incense, burning ghee (clarified butter) and flowers, fresh as well as decaying, enter the pilgrim's nostrils, and his ears are full of the sound of gongs, bells, and shouts of an excited crowd. While one's senses take in impressions like a camera with a wide open shutter, one's mind is choked as it were by an indescribable feeling of awe for the Great Mother Goddess in the middle of the holy chamber. See figure 12.

Kali's complexion is black—a shiny black which starkly contrasts with the red lustre of her tongue, palms of her hands and soles of her feet. Her blackness is, at once, strange and familiar. Why is Kali black? It is written in the Mahanirvana Tantra, “Just as all colors disappear in black so all names and forms disappear in Kali.” Sri Ramakrishna put the same truth into more colloquial terms:

You see her as black because you are far away from her. Go near and you will find her devoid of all color. The water of a lake appears black from a distance. Go near and take the water in your hand, and you will see that it has no color at all. Similarly, the sky looks blue from a distance. But look at the atmosphere near you; it has no color. The nearer you come to God, the more you will realize that he has neither name nor form. If you move away from the Divine Mother, you will find her blue, like the grass-flower. Is Shyama male or female? A man once saw the image of the Divine Mother wearing a sacred thread.11 He said to the worshipper: “What? You have put the sacred thread around the Mother's neck!” The worshipper said: “Brother, I see that you have truly known the Mother. But I have not yet been able to find out whether she is male or female; that is why I have put the sacred thread on her image.”12

A priest at the Dakshineswar Kali Temple explains Kali's blackness: “The Devi's complexion changed out of sheer wrath when she heard about the tyranny of the asuras over the Gods. Another interpretation is that she absorbs everything through the process of destruction. She absorbs vices such as hatred, malice, treachery, deceit, anger, passion, etc. Kali's black color means that she is inscrutable and cannot be known by worldly people full of ignorance. Darkness stands for ignorance.”

In dense darkness, O Mother, Thy formless beauty sparkles;

Therefore the yogis meditate in a dark mountain cave.

In the lap of boundless dark, on Mahanirvana's waves upborne,

Peace flows serene and inexhaustible.

Taking the form of the Void, in the robe of darkness wrapped,

Who art Thou, Mother, seated alone in the shrine of samadhi?

From the Lotus of Thy fear-scattering Feet flash Thy love's lightnings;

Thy Spirit-Face shines forth with laughter terrible and loud!13

Defiant with vibrant energy, Kali's full-breasted, youthful figure strides forward on the prostrate body of her divine husband Shiva—her right foot on his chest and the left one on his right thigh. Shiva lies motionless under her feet, stark nude and very white. His large, serene eyes look up and behold Kali—steady and eternally. Like the yin and yang, Kali and Shiva are one, yet harmoniously different.

Nude and dark, the blissful Divine Mother stands on the white bosom of the blissful Divine Father. Creation is not possible without bliss. Joy never comes from matter. Can anything material ever substitute for the bliss Kali and Shiva experience in their eternal union? Joy comes from the spirit. Kali is the ever-blissful Divine Mother, who gives joy to her divine spouse and to us, her divine children.

The vicinity of Shiva, her divine consort, arouses Kali's excitement. She begins to move and the three gunas14 begin to agitate rhythmically, creating and destroying. There is rhythm in creation, and there is rhythm in destruction. And it is all done in bliss. Mother loves to play the game of life and death, but once in a while, she stops and releases a soul or two, liberating them from karma and reincarnation. And then she laughs and claps her hands.

Kali is both real and symbolic. But what she is in herself cannot be described. She can only be known through her grace. Kali is self-illumined and beyond the human mind to comprehend. None knows her Supreme Form. Sings Ramprasad, the famous Kali mystic:

Who is there that can understand what Mother Kali is?

Even the six darshanas15 are unable to describe Her.

It is She, the scriptures say, that is the Inner Self

Of the yogi, who in Self discovers all his joy;

She that, of Her own sweet will, inhabits every living thing.

The macrocosm and microcosm rest in the Mother's womb;

Now do you see how vast it is? In the Muladhara

The yogi meditates on Her, and in the Sahasrara,

Who but Shiva has beheld Her as She really is?

Within the lotus ivilderness She sports beside Her mate, the Swan.

When man aspires to understand Her, Ramprasad must smile;

To think of knowing Her, he says, is quite as laughable

As to imagine one can swim across the boundless sea.

But while my mind has understood, alas! my heart has not;

Though but a dwarf, it still would strive to make a captive of the moon.16

For the one she chooses, Kali is an experience, an overwhelming experience. She exists as Kundalini, and like lightning, she reveals the Great Power. She is the experience; she is the bliss; and she is the giver of bliss. While she can be felt, she can never be defined because to define her would be to limit the Infinite by fitting it according to one's own personality. Kali is infinite and present at all times and at every place. Sri Ramakrishna described his experience of Cosmic Consciousness, thus:

The Divine Mother revealed to me in the Kali temple that it was she who had become everything. She showed me that everything was full of Consciousness. The image was Consciousness, the altar was Consciousness, the water vessels were Consciousness, the door-sill was Consciousness, the marble floor was Consciousness—all was Consciousness.

I found everything inside the room soaked, as it were, in Bliss-the Bliss of Satchidananda. I saw a wicked man in front of the Kali temple, but in him also I saw the Power of the Divine Mother vibrating.

That was why I fed a cat with the food that was to be offered to the Divine Mother. I clearly perceived that the Divine Mother herself had become everything—even the cat. The manager of the temple garden wrote to Mathur Babu saying that I was feeding the cat with the offering intended for the Divine Mother. But Mathur Babu had insight into the state of my mind. He wrote back to the manager: “Let him do whatever he likes. You must not say anything to him.”17

That which is Brahman is verily Shakti. I address That, again, as the Mother. I call It Brahman when It is inactive, and Shakti when It creates, preserves and destroys. It is like water, sometimes still and sometimes covered with waves.18

Shiva, in the Dakshineswar Kali Temple, lies on a “thousand-petalled” silver lotus which blooms atop an altar of stone with steps to the front, right and left. This altar is called the “vedi.” It has twelve columns made of silver which stand around the holy image of Kali. A costly canopy and a silver cornice hang above the altar. Behind the image of Kali is a decorative silver framework that resembles a burst of lightning, and behind that is a luxuriously embroidered brocade curtain in which priests hide incense and other offerings used for worship.

The priests had dressed Ma Kali in a red Varanasi silk sari with lavish gold embroidery. Although they dressed the image, they can never dress Kali herself. She is Digambari, She who is Naked, She who is clothed in Infinite Space. Kali, the Great Power, is unlimited and can never be contained by anything. She encompasses all but nothing can encompass her. North, east, west, south, up and down—each point of direction has a different deity. But Kali is everywhere.

She is naked and dark like a threatening rain cloud. She is dark, for she who is herself beyond mind and speech, reduces all things into that worldly “nothingness” which as the Void of all which we now know, is at the same time the All (purna) which is Light and Peace. . . . She stands upon the white corpse-like body of Shiva. He is white because He is the illuminating transcendental aspect of Consciousness. He is inert because he is the changeless aspect of the Supreme, and she the apparently changing aspect of the same. In truth, she and he are one and the same, being twin aspects of the One who is changelessness in, and exists as, change.19

Kali wears golden anklets, called nupur, which contain little rattles inside. They tinkle every time a priest touches her feet to offer scarlet jaba (hibiscus) and fresh bel leaves, made fragrant with sandal paste.

The actual image of Ma Kali is only thirty-three-and-a-half inches high, yet she appears much taller. Although her golden crown, decorated with countless tropical flowers, adds quite a few inches, it is mostly the emotional impact and awe she creates within the onlooker that magnifies her size substantially.

She is full of majesty. Her posture strangely combines the terror of destruction with the reassurance of motherly love. She is the Cosmic Power, the complete picture. Nothing is missing. All good (symbolized by her right side) and all bad (symbolized by her left side) is within her. She deals out death and terror while she offers fearlessness and boons to her devotees. A glorious harmony of opposites. She is all—energy and power.

Ma Kali looks alive and seems to be listening to the devotees at the front gate. “Ma, Ma go Ma!” they shout, each one trying to outdo the other—like children pulling their mother's skirt in order to get her attention.

Kali is a living Goddess. Once Sri Ramakrishna wanted to check whether the stone image of Kali in Dakshineswar was alive and tested the air under her nostrils. He held a piece of cotton under her nose and found that she breathed into his hand.

Kali has four arms, and each one is adorned with many ornaments made of gold and jewels. Around her wrist jingle bracelets—golden ones, red ones, and some made of conch shell. She has raised her upper right arm and, with this gesture, grants fearlessness to her devotees. Her lower right arm bestows boons. While her right two arms deal out good things, her left two arms threaten. Raised above her head, her upper left arm holds a blood-stained sword, and her lower left one tightly grips a freshly severed human head by its hair.

Golden chains glitter around her waist. Unlike other Kali images, the Kali image in Dakshineswar does not wear a terrible girdle made of severed demons' arms around her hips. The foundress of the temple garden looked upon Kali as Kumari (virgin) and didn't like the idea of demons' hands on her body. Hands are the principal instrument of work, and this girdle of cut-off hands worn by most Kali images represents human action as well as its resulting karma that has been taken back by Kali. At the close of a time cycle, all these merge back into the Great Mother.

Kali's ears are adorned with golden earrings that look like flowers, but upon closer view turn out to be small embryos. All life is Kali's. She gives it and takes it. The Devi says, “It is I who create the whole world and enter therein with prana, maya, and karma.”

Attached to the left nostril of her beautiful, slightly arched nose is a golden nose ring with a pearl drop. Kali has three eyes. Between the two large eyes on her forehead is a third one which symbolizes Divine Wisdom. This eye sees all and knows all—past, present, and future.

Around Kali's neck are numerous necklaces. There is the golden cheke,20 a golden necklace of thirty-two strings, a “chain of stars,” various pendants inlaid with precious stones, and a gruesome garland of fifty human skulls. This garland is called the “varnamala.”21 Each skull represents a letter of the alphabet.

The Garland of Letters illustrates this universe of names and forms, that is, speech (sabda) and its meaning or object (artha). Each letter is called an “akshara,” which translated means “that which undergoes no change.” Combinations of these aksharas become words which are expressed through the mouth. Each akshara has a male and female deity, and through the union of the two, creation evolves. Kali devours all and withdraws both into her undivided Consciousness at the time of dissolution. She wears the letters which she as a creatrix bore and then devours them again when she pleases.

Indo-European languages branched from the root of Sanskrit, said to be Kali's invention. She created the magic letters of the Sanskrit alphabet and inscribed them on the rosary of skulls around her neck.22 The letters were magic because they stood for primordial creative energy expressed in sound—Kali's mantras brought into being the very things whose names she spoke for the first time, in her holy language. In short, Kali's worshippers originated the doctrine of the Logos or creative Word, which Christians later adopted and pretended it was their own idea.23

Kali is Sound, the sound that created this universe. All knowledge is embedded in it. Name and form changes, but sound remains. Within ordinary human beings, three fourths of this sound remains unmanifested, and the only audible part is the gross sound, manifested daily through our mouths. But yogis can also hear the hidden sound, the transcendental sound.

Somehow, there is an irony in the fact that we verbally pray to her to listen to our needs when Kali, herself, is Sound. “Ma, if I express through my mouth, then only will you hear?” Sri Ramakrishna used to cry “Don't you see into my heart what an agony is going on in there? My mind is panting for you. Ma, don't you hear there?”

Ma Kali's tongue protrudes and blood trickles slowly from the sides of her mouth. Some say Ma Kali sticks out her tongue because she is shy like a village girl. People tell a story how she, thinking him a corpse, unwittingly stepped on her husband's body during the war against the demons, and at the moment of recognition, she recoiled and bashfully stuck out her tongue. Another, more philosophical, explanation says that Kali, through the tongue, is expressing sound and is thereby creating the universe.

And still another interpretation says that Kali's white teeth stand for the white sattva guna, her red tongue stands for the red raja guna, and her black skin stands for delusion which is associated with the tama guna. Kali stretches out her tongue because she wants to conquer her devotees' tama guna by increasing their raja guna. And then she conquers their raja guna by cutting it with her large white teeth. Through the sattva guna, she leads her devotees toward salvation.

There is a lot of noise in the small shrine. Devotees shout, priests shout. “Ma, oh Ma, Ma go Ma!” Attending priests keep flinging so many hibiscus garlands at Ma Kali's feet that Shiva is barely visible. Actually, Kali, also, wears so many flower garlands that it's hard to see her body beneath. Most visitors to the Kali temple rarely ever see the Garland of Skulls because she is so covered with fresh flowers.

On the steps of the altar stand vessels which hold her drinking water, and on the large silver lotus next to the image of Shiva is a small lion made of eight metals, a poisonous gosap (snake) and Shiva's trident. On Kali's left side, next to the silver lotus on the upper step, stands the image of a jackal. The animal's head is tilted upward as if preparing to howl. Staring at Kali in adoration, blood drips out of its slightly open mouth. Also on the upper step but facing front is a small silver throne which holds Ramlala—the boy Ramachandra—made of precious metals. To the left of Ramlala is the image of a black bull. This is Nandi, Shiva's carrier.

Facing front on the altar's upper step is a large photograph of Sri Ramakrishna. Its frame leans against the silver column on Kali's right. Sri Ramakrishna's photo has been decorated with white sandalwood paste and tulsi leaves and is surrounded with a thick flower garland. On the other side of the same step, leaning against the silver column to Kali's left, is a large photograph of Sri Sarada Devi, wife and spiritual consort of Sri Ramakrishna. It also has been decorated with red sandalwood paste and a scented flower garland.

On the altar's lower step, to the side of Sri Ramakrishna's photograph, is a magnificent large shell. It is used to invoke and worship the Goddess Lakshmi, the Goddess of fortune. Priests pour Ganges water into the shell's large mouth and then invoke the Goddess Lakshmi into it. On the same step, but facing front, is Ma Chandi—a copy of the Tantra scripture wrapped in a red cloth. A little farther over is a golden box containing a holy shalagram24 and a Shiva linga25 called Baneswar. Next to the golden box, below the photo of Sri Sarada Ma, is a colorful image of Ganesha, the elephant God, whom Hindus consider to be the God of success.

The altar steps on either side are used by priests who climb up to attend to Ma Kali. In great reverence, they stand or kneel on these steps when they need to get close to worship her with various articles or when they need to exchange her fading flowers with fresh ones.

On the marble floor in front of the altar is a clay pitcher filled with Ganges water, which is used in ritual worship. This pitcher is called mangal-ghata and is rarely visible since it is almost always completely covered with garlands, leaves, and flowers. During the morning worship this ghat is surrounded by puja vessels, flowers, and food offerings. The worshipping priest sits on a small mat (called asana) before the ghat, and on his left side is a fairly large glass container which holds a steadily burning ghee light.26

Behind the pujari's seat to the south is the front entrance. People rarely enter the shrine from the front except on special occasions, such as Kali Puja. Pilgrims generally are only allowed to come up to the iron gate that blocks the entrance to the inner shrine. There, they get darshan of Ma Kali and hand priests their offerings, who, in turn, throw their long hibiscus garlands with expert precision around Ma Kali's feet.

In a way, the Kali priests in Dakshineswar appear noticeably different. They behave with a certain kind of contentment that reminds one of the satisfied face of a recently-fed child sitting on its mother's lap. There is also something curiously striking about their eyes—a kind of brilliant lustre. One could put all sorts of adjectives together and still have difficulty defining exactly what it is that makes their eyes look that way.

As the crowd pushes toward the front gate, a multitude of hands stretches out toward the priests, whose white clothing exhibits numerous flower and vermillion stains. The priests often must shout to keep the crowd at bay. Leaning over the gate and the mass of bodies, they attend to one pilgrim after the other. It's physically exhausting because they have to work very fast. Each pilgrim wants to drink a drop of Kali's charanamrita,27 be marked with her holy sindur (vermillion paste), and receive prasad from the priest's hands. In return for the favor, priests receive dakshina, a gift of money which is almost their sole source of income. The base salary they receive from the temple is extremely small.

In the southwestern corner of the shrine stands a pail which contains Ma Kali's charanamrita. Next to it, the priests keep a gong and sticks used to beat a large kettle drum during arati (vespers). On the wall a little east of the front entrance, hangs a chamar28 with a silver handle. The pujari uses it to fan Ma Kali during arati in the hot summer season.

Shoved into the southeastern corner of the shrine lies a good-sized heap of predominantly red flowers. These are flowers which have already been used for worship. Since the constant flow of pilgrims delivers large quantities of garlands and flowers for Ma Kali, the priests periodically have to take them off the silver lotus she stands on. Otherwise Ma would disappear behind a mountain of flowers. They toss them into the corner, and when the flower heap becomes too big, a servant comes, puts them into a huge basket and carries them out on his head. Another reason for disposing and sweeping up the offered flowers and leaves is that devotees consider it highly inauspicious to step on Kali's flowers.

A large wooden chest, containing some of Kali's ornaments and some utensils, stands against the eastern wall of the shrine. Right next to it is Ma Kali's bed, where, under a light-green mosquito curtain, she takes rest during siesta and sleeps at night. When it is time to retire, the priests put the Mother to bed by putting a picture of Kali onto the pillow. Then they draw the mosquito curtain, so that Ma Kali may rest undisturbed. They treat Ma Kali as if she were a human being because, this way, they can lovingly worship her. When one considers who Ma Kali really is, one would never dream of offering food to her or making her rest on a bed.

Kali is the Mistress of Time,29 the cause of worldly change, and as such, she consumes all things. All beings and all things must yield to her in the end—our desires and hopes, our family, romantic ties, our friends, possessions and hard-earned success in business. As the eternal, indifferent Time she confronts man with his pitiful finite attachments, swallows them up, and produces them again in a different form, in a different time.

God created the universe and then entered into it, veiling his divinity with his bewitching maya. Through Kali's grace, a spiritual aspirant can tear those veils.

Hindus view time as cyclical. One cycle is divided into four yugas: krta, or the Golden Age (1,728,000 years), treta (1,296,000 years), dvapara (864,000 years), and kali, the Iron Age (432,000 years). Each cycle of the four yugas is called a mahayuga and lasts for 4,320,000 years. One thousand mahayugas, or 4,320,000,000 years, is equal to one day in Brahma's30 life which sees the creation of the world in the morning and its dissolution in the evening. Brahma lives for 100 Brahma years or 311,040,000,000,000 human years, and then he, himself, dissolves for a Brahma century during which nothing exists but primeval substance until the great cycle begins again.31

Kali is the devourer of Time (kala) and then resumes her own dark formlessness. Each division of time has a different deity, and each smaller division is swallowed by a higher one. Thus, a second is swallowed by a minute, a minute by an hour, a day is swallowed by night and both are consumed by a week. A year disappears into an age which is consumed by a cycle, and a cycle is swallowed whole by Ma Kali.

Taking an example out of everyday life, Sri Ramakrishna explained the dissolution and evolution concept of creation in a way that everybody can understand:

After the destruction of the universe, at the end of a great cycle, the Divine Mother garners the seeds for the next creation. She is like the elderly mistress of the house, who has a hotchpotch pot in which she keeps different articles for household use.

Oh, yes! Housewives have pots like that where they keep blue pills, small bundles of seeds of cucumber, pumpkin, and gourd, and so on. They take them out when they want them. In the same way, after the destruction of the universe, my Divine Mother, the Embodiment of Brahman, gathers together the seeds for the next creation. After the creation the Primal Power dwells in the universe itself. She brings forth this phenomenal world and then pervades it. In the Vedas creation is likened to the spider and its web. The spider brings the web out of itself and then remains in it. God is the container of the universe and also what is contained in it.”32

On the northern wall behind the image of Kali hang two swords. They look used. Though the Dakshineswar Temple does not perform animal sacrifices as often as some other temples dedicated to the Great Mother, on a few special days throughout the year, a designated person uses one of these swords to decapitate the animal. These swords have hung there for a long time and were there during Sri Ramakrishna's time. Sri Ramakrishna described a dramatic experience during his early God-intoxicated period. Out of desperation, he almost used Kali's sword:

I felt as if my heart was being squeezed like a wet towel. I was overpowered with a great restlessness and a fear that it might not be my lot to realize Her in this life. I could not bear the separation from Her any longer. Life seemed to be not worth living. Suddenly my glance fell on the sword that was kept in the Mother's temple. I determined to put an end to my life. When I jumped up like a madman and seized it, suddenly the blessed Mother revealed Herself. The buildings with their different parts, the temple, and everything else vanished from my sight, leaving no trace whatsoever, and in their stead I saw a limitless, infinite, effulgent Ocean of Consciousness. As far as the eye could see, the shining billows were madly rushing at me from all sides with a terrific noise, to swallow me up! I was panting for breath. I was caught in the rush and collapsed, unconscious. What was happening in the outside world I did not know; but within me there was a steady flow of undiluted bliss, altogether new, and I felt the presence of the Divine Mother.”33

Three large paintings and a clock hang next to the two swords on the back wall—Ma Tara, Sri Chaitanya, and one picture of Smashana Kali. Mother Kali's shrine hasn't changed much in over a 100 years with the exception of a few commodities that represent technology of our modern age. There are a couple of electric fans that help keep the pujari cool during the summer months, and there is an intercom telephone on the western wall next to the side entrance to Kali's inner shrine. Priests use this phone to communicate with temple authorities at the office.

While the crowd of pilgrims mostly enters Kali's temple through the front doors from the south, priests and the Mother's servants either enter the temple on the side through the western doorway or through the northern entrance in the back. Both these entrances lead into a covered veranda which one first has to pass through in order to reach the inner shrine. Priests often utilize the veranda's cool shade to chat or to take rest between worship services. Servants often prepare offerings there, and musicians with gongs and large drums wait there for the next arati.

The side entrance is a fairly narrow passageway, and like the inside shrine, it also has blue tiles. It is about three to four feet deep, and on its left side is a closet which serves as temporary storage of flowers offered to Kali. Periodically, a servant empties the closet, carrying the flower offerings in an enormous basket on his head toward the Ganges.

Like the front entrance, the side entrance to the inner sanctum of Kali has a couple of wide steps and a cast-iron gate. But unlike the front entrance, immediately after the gate is a large black step resembling a beam on a ship one needs to climb over to get inside a cabin. This step is made of basalt. All who enter the Kali temple are extremely careful not to touch this black step with their feet, and should somebody's foot accidentally touch it, priests immediately clean it with Ganges water and worship it. In the middle of this step is a large crack.

The story goes that once a tremendous thunderstorm hit Dakshineswar, and Sri Ramakrishna, looking out of his room across the courtyard, observed lightning striking the Kali temple. He knew that one priest was on duty inside the temple and prayed fervently to Ma Kali to save his life. Although the temple shook from the impact of the lightning bolt, it was not destroyed and the priest came out unharmed. The only visible damage was a large crack in the black step of the side entrance leading to the inner sanctum. And since then, people carefully avoid touching it with their feet. Rather, they bow down their heads and touch the step with reverence. Another reason this step is revered is that this same substance, basalt, was used to create the image of Kali.

Both entrances to the inner sanctum have strong cast-iron doors which are closed during siesta and at night to protect Ma Kali from intruders. Vermillion stains are all over these doors—hands have touched them with reverence, and zealous pilgrims have held on to them, trying to feel the Great Mother Goddess Kali.

Kali is not what one imagines a typical Hindu woman to be. She is neither gentle, bashful, nor subservient toward her husband. She moves around in the nude; her hair is dishevelled; and she gets intoxicated from drinking the blood of demons.

Kali is a Goddess who fights alone. And if she wants help, she accepts it from other females but does not seek it from men. Whenever the male Gods are unable to subdue the demons in battle, they ask the Great Mother Goddess for help, and not until after she has scored a victory can they go back in peace and perform their normal godly duties.

The fact that Ma Kali is black makes one wonder whether this Goddess originated with an ancient African super culture. Most scholars don't believe she is ancient. They call her a relatively “young” Goddess who did not reach full popularity in India until the 18th or 19th century. Their opinion is based on the Vedas which are perhaps the most ancient scriptures in the world. They hardly mention Kali. The earliest references to Kali are found in the Mundaka Upanishad, in the Puranas, dating back to the early medieval period—around A.D. 600.

But, one asks, what about the time before the Vedas were conceived? Could it be that God in ancient times was a She? According to Judeo-Christian tradition, this idea is “unthinkable,” but if one seriously studies history with an open mind, one cannot exclude the possibility of a Great Mother Goddess that reigned long before the Father God appeared. Primitive man, observing women giving birth, perceived her as magic and prayed to her to make his tribe strong and give him more sons and daughters.

Dating back to Neolithic times, the most ancient images found were always female and depicted fertility. Many are black and mysteriously related. One can't help but ask, “Was the Black Goddess Kali at one time worshipped by peoples all over the world?” Modern research by Westerners certainly points in this direction.

We find Kali in Mexico as an ancient Aztec Goddess of enormous stature. Her name is Coatlicue, and her resemblance to the Hindu Kali is striking.

The colossal Aztec statue of Coatlicue fuses in one image the dual functions of the earth which both creates and destroys. In different aspects she represents Coatlicue, “Lady of the Skirt of Serpents” or “Goddess of the Serpent Petticoat”; Cihuacoatl, “the Serpent Woman”; Tlazolteotl, “Goddess of Filth”; and Tonantzin, “Our Mother,” who was later sanctified by the Catholic Church as the Virgin of Guadalupe, the dark-faced Madonna, la Virgen Morena, la Virgen Guadalupana, the patroness and protectoress of New Spain; and who is still the patroness of all Indian Mexico. In the statue her head is severed from her body, and from the neck flow two streams of blood in the shape of two serpents. She wears a skirt of serpents girdled by another serpent as a belt. On her breast hangs a necklace of human hearts and hands bearing a human skull as a pendant. Her hands and feet are shaped like claws. From the bicephalous mass which takes the place of the head and which represents Omeyocan, the topmost heaven, to the world of the Dead extending below the feet, the statue embraces both life and death. Squat and massive, the monumental twelve-ton sculpture embodies pyramidal, cruciform, and human forms.

As the art critic Justino Fernández writes in his often-quoted description, it represents not a being but an idea, “the embodiment of the cosmic-dynamic power which bestows life and which thrives on death in the struggle of opposites.”34

We find Kali in ancient Crete as Rhea, the Aegean Universal Mother or Great Goddess, who was worshipped in a vast area by many peoples.

Rhea was not restricted to the Aegean area. Among ancient tribes of southern Russia she was Rha, the Red One, another version of Kali as Mother Time clothed in her garment of blood when she devoured all the gods, her offspring. The same Mother Time became the Celtic Goddess Rhiannon, who also devoured her own children one by one. This image of the cannibal mother was typical everywhere of the Goddess as Time, who consumes what she brings forth; or as Earth, who does the same. When Rhea was given a consort in Hellenic myth, he was called Kronus or Chronos, “Father Time,” who devoured his own children in imitation of Rhea's earlier activity. He also castrated and killed his own father, the Heaven-God Uranus; and he in turn was threatened by his own son, Zeus. These myths reflect the primitive succession of sacred kings castrated and killed by their supplanters. It was originally Rhea Kronia, Mother Time, who wielded the castrating moon-sickle or scythe, a Scythian weapon, the instrument with which the Heavenly Father was “reaped.” Rhea herself was the Grim Reaper... .35

We find Kali in historic Europe. In Ireland, Kali appeared as Caillech or Cailleach, an old Celtic name for the Great Goddess in her Destroyer aspect.

Like Kali, the Caillech was a black Mother who founded many races of people and outlived many husbands. She was also a creatress. She made the world, building mountain ranges of stones that dropped from her apron.

Scotland was once called Caledonia: the land given by Kali, or Cale, or the Caillech. “Scotland” came from Scotia, the same Goddess, known to Romans as a “dark Aphrodite”; to Celts as Scatha or Scyth; and to Scandinavians as Skadi.

Like the Hindus' destroying Kalika, the Caillech was known as a spirit of disease. One manifestation of her was a famous idol of carved and painted wood, kept by an old family in County Cork, and described as the Goddess of Smallpox. As diseased persons in India sacrificed to the appropriate incarnation of the Kalika, so in Ireland those afflicted by smallpox sacrificed sheep to this image. It can hardly be doubted that Kalika and Caillech were the same word.

According to various interpretations, “caillech” meant either an old woman, or a hag, or a nun, or a “veiled one.” This last apparently referred to the Goddess's most mysterious manifestation as the future, Fate, and Death—ever veiled from the sight of men, since no man could know the manner of his own death.

In medieval legend the Caillech became the Black Queen who ruled a western paradise in the Indies, where men were used in Amazonian fashion for breeding purposes only, then slain. Spaniards called her Califia, whose territory was rich in gold, silver, and gems. Spanish explorers later gave her name to the newly discovered paradise on the Pacific shore of North America, which is how the state of California came to be named after Kali.

In the present century, Irish and Scottish descendants of the Celtic “creatress” still use the word “caillech” as a synonym for “old woman.”36

The Black Goddess was known in Finland as Kalma (Kali Ma), a haunter of tombs and an eater of the dead.”37

The Black Goddess worshipped by the gypsies was named Sara-Kali, “Queen Kali,” and to this present day, Sara is worshipped in the South of France at Ste-Marie-de-la-Mer during a yearly festival.

Some gypsies appeared in 10th-century Persia as tribes of itinerant dervishes calling themselves Kalenderees, “People of the Goddess Kali.” A common gypsy clan name is still Kaldera or Calderash, descended from past Kali-worshippers, like the Kele-De of Ireland.

European gypsies relocated their Goddess in the ancient “Druid Grotto” underneath Chartres Cathedral, once the interior of a sacred mount known as the Womb of Gaul, when the area was occupied by the Carnutes, “Children of the Goddess Car.” Carnac, Kermario, Kerlescan, Kercado, Carmona in Spain, and Chartres itself were named after this Goddess, probably a Celtic version of Kore or Q're, traceable through eastern nations to Kauri, another name for Kali.

The Druid Grotto used to be occupied by the image of a black Goddess giving birth, similar to certain images of Kali. Christians adopted this ancient idol and called her Virgo Paritura, “Virgin Giving Birth.” Gypsies called her Sara-Kali, “the mother, the woman, the sister, the queen, the Phuri Dai, the source of all Romany blood.” They said the black Virgin wore the dress of a gypsy dancer, and every gypsy should make a pilgrimage to her grotto at least once in his life. The grotto was described as “your mother's womb.” A gypsy pilgrim was told: “Shut your eyes in front of Sara the Kali, and you will know the source of the spring of life which flows over the gypsy race.”38

We find variations of Kali's name throughout the ancient world.

The Greeks had a word Kalli, meaning “beautiful,” but applied to things that were not particularly beautiful such as the demonic centaurs called “kallikantzari,” relatives of Kali's Asvins. Their city of Kallipolis, the modern Gallipoli, was centered in Amazon country formerly ruled by Artemis Kalliste. The annual birth festival at Eleusis was Kalligeneia, translatable as “coming forth from the Beautiful One,” or “coming forth from Kali.”

Lunar priests of Sinai, formerly priestesses of the Moon-Goddess, called themselves “kalu.” Similar priestesses of prehistoric Ireland were “kelles,” origin of the name Kelly, which meant a hierophantic clan devoted to “the Goddess Kele.” This was cognate with the Saxon Kale, or Cale, whose lunar calendar or kalends included the spring month of Sproutkale, when Mother Earth (Kale) put forth new shoots. In antiquity the Phoenicians referred to the strait of Gibraltar as Calpe, because it was considered the passage to the western paradise of the Mother.39

The Black Goddess was even carried into Christianity as a mother figure, and one can find all over the world images of Mother Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ, depicted as a black madonna.

When a spiritual aspirant has formed a special relationship with Kali, she is no longer just an image in a temple. Her presence fulfills this person's being at all times. In a way, all religions prescribe methods for getting in touch with God. While the methods differ, the outcome is the same. For instance, the person practicing Tantra, in the end, reaches the same goal as the person practicing Vedanta.

A Tantric yogi sees the great Mother present within his human body as the Kundalini. She lies liidden by her self-created ignorance, like a snake, coiled and fast asleep in the muladhara chakra at the bottom of the spinal cord. Through sadhana, the Tantric awakens the Mother and rouses her to go upward. Flashing like a phosphorescent flame through the Sushumna channel, she pierces the various chakras until she reaches the highest plane and unites with Shiva at the crown of the head. At this moment, the Tantric experiences such supreme bliss that his mind cannot contain the small ego-consciousness and becomes illumined. Yet Tantric sadhana does not end there. The perfect realization of the Mother only culminates when one experiences illumination in all planes, even the lowest.

A Vedantist, on the other hand, has a totally different approach. The Vedantist does not like to see Gods and Goddesses and believes that whatever he or she sees in this world is unreal, a play of name and form. He or she even sees the mind as a material entity. Yet, although the mind is devoid of consciousness, it has the ability to function like a mirror and reflect consciousness. For instance, when a pot is placed before one's eyes, one's mind takes its form, and then the light of the Atman (the Self) manifests the pot. One cannot experience or perceive anything without the light of the Atman. The difference between an ordinary person and an illumined soul is that an illumined soul is conscious of the fact that he or she experiences Brahman in every state of the mind, even in the lowest.

Sri Ramakrishna wanted to experience the Truth as taught by different religions. After attaining illumination by worshipping Kali, he practiced the disciplines of other religions, and then said from first-hand knowledge, “As many faiths, so many paths.”

Sri Ramakrishna learned Tantra from Bhairavi Brahmani, an attractive female saint who traveled from place to place and taught a chosen few the secrets of Tantra. Sri Ramakrishna sometimes spoke about his Tantric sadhana:

The Brahmani made me undertake one by one, all the disciplines prescribed in the sixty-four main Tantras, all difficult to accomplish, in trying to practice which most of the Sadhakas go astray; but all of which I got through successfully by Mother's grace. On one occasion, I saw, that the Brahmani had brought at night—nobody knew whence—a beautiful woman, nude and in the prime of her youth, and said to me, “My child, worship her as the Devi.” When the worship was finished, she said, “Sit on her lap, my child, and perform Japa.” I trembled and wept, calling to the Mother, “O Mother, Mother of the universe, what is this command Thou givest to one who has taken absolute refuge in Thee? Has Thy weak child the power to be so impudently daring?” But as soon as I had called on her, I felt as if I was possessed by some unknown power and extraordinary strength filled my heart. And no sooner had I, uttering the Mantras, sat on the lap of the woman, like one hypnotized, unaware of what I was doing, than I merged completely into samadhi. When I regained consciousness, I saw the Brahmani waiting on me and assiduously trying to bring me back to normal consciousness. She said, “The rite is completed, my child; others restrain themselves with very great difficulty under such circumstances and then finish the rite with nominal Japa for a trifling little time only; but you lost all consciousness and were in deep samadhi.” When I heard this, I became reassured and began to salute Mother again and again with a grateful heart for enabling me to pass that ordeal unscathed.

On another occasion, I saw that the Brahmani cooked fish in the skull of a dead body and performed Tarpana. She also made me do so and asked me to take that fish. I did as I was asked and felt no aversion whatever.

But, on the day when the Brahmani brought a piece of rotten flesh and asked me to touch it with my tongue after Tarpana, I was shaken by aversion and said, “Can it be done?” So questioned, she said, “What's there in it, my child? Just see, I do it.” Saying so, she put a portion of it into her mouth and said, “Aversion should not be entertained,” and placed again a little of it before me. When I saw her do so, the idea of the terrible Chandika form of the Mother Universal was inspired in my mind; and repeatedly uttering “Mother,” I entered into Bhavasamadhi. There was then no aversion felt when the Brahmani put it into my mouth.40

Many people ridicule or look down on Tantra as a religion, because Tantra prescribes a non-traditional sadhana they consider blasphemous. The Tantric offers to the Divine Mother panca-makara, or the five items of worship: fish, meat, parched cereals or money, wine and sexual union.

... If they had read the Tantra Shastra intelligently and learned its principles from Sadhakas truly versed in it, they would have realized how mistaken were their notions of it, and, instead of despising it, would certainly have admitted that this Shastra is the only means of Liberation for the undisciplined, weak-minded and short-lived. Seeing that wine, flesh, fish are consumed and sexual intercourse takes place in the world at large, I am myself unable to understand why many people shudder at the Sadhana of Panca-makara to be found in the Tantra Shastra. Do these acts become blameable only if made a part of worship?41

Yet Tantric sadhana should not be mistaken as a license to indulge. Some people forget that the results of Tantric practices can only be obtained if the aspirant resorts to austere self-control as the basis of the disciplines. They engage in promiscuous practices for which the Tantras themselves are being held responsible. One needs a competent teacher to practice Tantra. Great energy such as lightning, such as the Kundalini, can be a great danger if not channeled properly.

Depending on an aspirant's disposition, Tantra will prescribe a particular method for spiritual practice. In general, the Tantras classify people into three major groups—pasu (animal), vira (hero), and divya (godlike). Inertia is the predominant quality of the pasu, who is deluded, negligent, indolent, and spends an excessive amount of time sleeping. The hero, on the other hand, is full of excessive energy which results in desire, anger, greed, pain, and attachment. He is aggressive and cultivates a fearless stance before Kali, challenging her to unveil her secrets. But the godlike devotee is calm, has wisdom, knowledge and a kind disposition.

Since the pasu aspirant is ignorant of the real meaning of Tantric rites, he or she is not permitted to worship the Divine Mother with fish, meat, parched cereals, wine, and sexual union. Instead, this aspirant is supposed to worship her with substitutes such as eggplant, red radish, lentils, ginger, wheat, beans, and garlic. The pasu is supposed to substitute milk, ghee or honey for wine and meditates on her feet in lieu of sexual union.

The hero, who has acquired purity and strength of character, is permitted by the Shakta Tantras to worship the Divine Mother with fish, meat, parched cereals, wine, and through sexual union. In order to transcend and subdue his restless and excitable nature, the hero aspirant offers these five articles of enjoyment to the Mother while repeating mantras.

The godlike aspirant is self-restrained, tranquil, silent—possessed of a sattvic disposition. He or she is truthful, not fanatic, compassionate, and respectful to all women as manifestations of the Divine Mother. The godlike aspirant has firm faith in the guru, mantra, and yantra42. This aspirant performs japam at night and worships the Mother three times a day, practicing breath control, concentration, and meditation. Through this steadfast spiritual practice, the godlike aspirant rouses the Kundalini and makes her pierce the six centers of mystic consciousness.

A godly aspirant is an adept in meditation on the Divine Mother at the centers of mystic consciousness and experiences Her in them and the universe. He transcends the plane of duality and distinction and partakes of Her supreme undifferentiated consciousness and delight. He dissolves his mind, eradicates his ego (aham), and annuls the world of phenomenal appearances (idam). He harmonizes and synthesizes duality and distinction in unity, and attains fulfillment (siddhi). He acquires the integral knowledge and the intuitive experience. Saktaism is the practical science of attaining the Advaita Vedanta knowledge and Absoluteness (sivatva). It is sheer nonsense and gross perversion of the truth to brand it as gross egoistic hedonism or unrestrained sensualism. Rama Prasada, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Bama Ksepa [Bamakhepa], and other Sakta saints attained God-realization through the Sakta cult of spiritual discipline. Sri Aurobindo based his Integral Yoga on this cult, adapted, simplified and rationalized it for the upliftment of humanity to the supramental level.43

The aim of all Tantric practices is to bring aspirants to the realization that the very objects which tempt human beings and make them experience repeated births and deaths are none other than the veritable forms of God. Contrary to ancient history in which we find that nearly every phase and activity of human life was holy, modern people have moved God to a far-away place called heaven.

Tantric sadhana helps spiritual seekers to bring God back into the human heart and into everything that concerns life—to adore God with body, mind, and words. When we eat, sleep, or go to work, we should do so in worship of God. Every action should be done in glorification of the Divine Mother.

Sri Ramakrishna used to say that true devotees must love and think about God so much that they develop a kind of “love body.” This body feels different from the body of an ordinary person. We cannot compare the upsurge of joy we feel during ecstasy with any kind of worldly joy. Sri Ramakrishna said:

Mad, that's the word. One must become mad with love in order to realize God. But that love is not possible if the mind dwells on lust and gold. Sex-life with a woman! What happiness is there in that? The realization of God gives ten million times more happiness. Gauri used to say that when a man attains ecstatic love of God, all the pores of the skin, even the roots of the hair, become like so many sexual organs, and in every pore the aspirant enjoys the happiness of communion with the Atman.44

While Sri Ramakrishna urged his disciples to love God without any reservation, he warned and asked them not to practice the heroic attitude toward the Divine Mother. It is a very slippery path, he often said. He asked them to worship Shakti with a mother/child attitude because this kind of relationship kindles purity in an aspirant's mind. It's the safest and easiest path in this kali yuga. The heroic aspirant has every chance of falling and, instead of transcending sense pleasures, becoming very attached and obsessed with them. A pure mind is absolutely necessary to reach the goal. Sri Ramakrishna taught how to worship Shakti as the Divine Mother:

Shakti alone is the root of the universe. That Primal Energy has two aspects: vidya and avidya. Avidya deludes. Avidya conjures up lust and greed which casts the spell. Vidya begets devotion, kindness, wisdom, and love, which lead one to God. This avidya must be propitiated, and that is the purpose of the rites of Shakti worship.45

The devotee assumes various attitudes toward Shakti in order to propitiate her: the attitude of a handmaid, a hero, or a child. A hero's attitude is to please her even as a man pleases a woman through intercourse.

The worship of Shakti is extremely difficult. It is no joke. I passed two years as the handmaid and companion of the Divine Mother. I used to dress myself as a woman. I put on a nose ring. One can conquer lust by assuming the attitude of a woman. But my natural attitude has always been that of a child toward its mother. I regard the breasts of any woman as those of my own mother.46

Pray to the Divine Mother with a longing heart. Her vision dries up all craving for the world and completely destroys all attachment to lust and greed. It happens instantly if you think of her as your own mother. She is by no means a godmother. She is your own mother. With a yearning heart persist in your demands on her. The child holds to the skirt of its mother and begs a penny of her to buy a kite. Perhaps the mother is gossiping with her friends. At first she refuses to give the penny and says to the child: “No, you can't have it. Your daddy has asked me not to give you money When he comes home I'll ask him about it. You will get into trouble if you play with a kite now.” The child begins to cry and will not give up his demand. Then the mother says to her friends: “Excuse me a moment. Let me pacify this child.” Immediately she unlocks the cash box with a click and throws the child a penny.

You too must force your demand on the Divine Mother. She will come to you without fail. I once said the same thing to some Sikhs when they visited the temple. We were conversing in front of the Kali temple. They said, “God is compassionate.” “Why compassionate?” I asked. “Why, revered sir, he constantly looks after us, gives us righteousness and wealth, and provides us with our food.” “Suppose,” I said, “a man has children. Who will look after them and provide them with food—their father or a man from another village?’” God is our very own. We can exert force on him. With one's own people one can even go so far as to say, “You rascal! Won't you give it to me?”47

But in order to get everything from the Divine Mother, one needs to surrender to her. There is one Tantric sadhana, called anga-nyasa, wherein the aspirant is asked to consecrate the different parts of his or her body to the Mother by placing the different letters, both vowels and consonants, on them. During this practice one is to feel that every part of the physical body, with all its biological processes going on within, really belongs to the Mother and not to oneself.

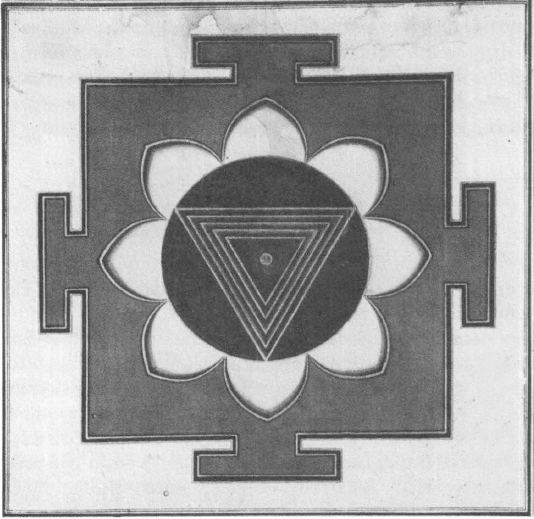

Tantric sadhana uses symbols in the form of mantras and yantras. Kali in her seed mantra (bija-mantra) is KRĪM. This mantra is a sound representation of the Mother. While the inner meaning of this mantra can only be understood in deep meditation, the word meaning is as follows: K stands for full knowledge, R means she is auspicious, Ī means she bestows boons, and M that she gives freedom. Through the repetition of her mantra, OM KRĪM KALI, the aspirant's mind becomes divinely transformed and passes from the gross state of worldly affairs into Kali's subtle light of pure Consciousness. See figure 13.

Kali in her yantra form is the Supreme Generative Energy in the central point, or bindu, enclosed by three pentagons (actually five inverted concentric triangles), a circle and an eight-petalled lotus. While the triangle within a female deity's yantra points downward, it points upward within a male deity's yantra. But the bindu48 in the heart of the Kali yantra is in the same position as the one in the Shiva yantra. This symbolizes the oneness of the Supreme Female Principle with the Supreme Male Principle—Kali, as the energy aspect of material nature, is united with the Absolute (Shiva) for the sake of creation.

Figure 13. Krīm, seed mantra of the Goddess Kali.

The Kali yantra (figure 14), above is both an object existing in the external world as well as a subject to be internalized within the human body. Kali is presented here as Prakriti, symbolized by the eight-petalled lotus, since she is the cause of material nature. The eight petals stand for the eight elements of Prakriti—earth, water, fire, air, ether, mind, intellect, and ego-sense—of which this phenomenal world is composed. The circle symbolizes the circle of life and death which we must pierce in order to reach the Absolute Reality. The fifteen corners of the five inverted concentric triangles represent the fifteen psychophysical states—five organs of knowledge (sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch), five organs of action (hands, feet, speech, organ of evacuation, and organ of procreation), five vital airs (prana—upward air; apana—downward air; vyana—air within the body; udana—air leaving the body; and samana—air at the navel which helps to digest food).

Kali is the mystical indweller in every human body. When she lies in the Muladhara lotus like a sleeping serpent at the base of the spinal cord, she is called Kundalini. When, through yogic disciplines, she becomes aroused, pierces the Sushumna channel and rises upward, she has different names, depending on the chakra in which she resides. In the heart chakra, she is called Hamsa, and in the chakra between the eyebrows, she is called Bindu. Once she reaches the Sahasrara chakra at the crown of the head, she becomes formless, transcendental consciousness.

A yogin should open the door to liberation through Kundalini. The individual soul should meditate on itself as a spirit in the heart-lotus, on Kundalini in the Muladhara lotus and on the Supreme Self or Parama Siva in the Sahasrara. It should be united with Parama Siva by rousing Kundalini and making her pierce the higher lotuses and ascend to the highest lotus. It cannot be united with Him or become identical with Him without the aid of Kundalini. She is the mediator between the jivatman and Parama Siva although She is non-different from Him. Kundalini, coiled Divine Power, or dormant power of universal consciousness, exists everywhere in the universe. Matter, life, mind, and superconsciousness are different degrees of the unveiling of the dormant power of consciousness. Even in an atom of matter there is coiled Kundalini in the nucleus. Matter is dormant power of consciousness. Divine Power assumes the forms of the individual souls by limiting Herself, and of matter by coiling Herself or by becoming dormant.49

One's own body is the best place for worship. There is a unique group of traveling minstrels in Bengal, called Bauls. They practice their own form of Tantric disciplines. They are free thinkers who believe that temples, mosques and churches stand across the path to truth, blocking the search. They say the search for God is one which everyone must carry out for himself or herself. It's an inner journey within one's own body—the greatest temple of all. Sri Ramakrishna was very fond of Bauls. He told Holy Mother that he would have to be born again and would return as a Baul in a northwesterly direction from Dakshineswar.

The human body, according to the Tantricas, is the best medium for realizing the truth. This body is not merely a thing in the universe, it is an epitome of the universe, a microcosm in relation to the macrocosm. There is therefore nothing in the universe which is not there in the body of a man. With this idea in view, the Tantrica sadhikas have tried to discover the most important rivers in the nerve system of man, the mountains specially in the spinal cord, and the prominent tirthas (holy places) in different parts of the body, and the sun and the moon—time element of the exterior universe in all its phases as day and night, fortnight, month and year—have often been explained with reference to the course of the vital wind (prana and apana—exhalation and inhalation). The human form is thus the abode of the truth of which the universe is the manifestation in infinite space and eternal time. Instead of being lost in the vastness of the incomprehensible universe and groping in its unfathomable mystery, a Tantric sadhaka prefers to concentrate his attention on himself and to realize the truth hidden in this body with the clear conviction that the truth that is realized within is the same truth that pervades and controls the whole universe.50

Overwhelmed with God-consciousness, Sri Ramakrishna used to say, “I am the machine and She is the Operator. I am the house and She is the Indweller. I am the chariot and She is the Charioteer. I move as She moves me; I speak as She speaks through me.”51

He saw Kali in all women.

Sri Ramakrishna said to his disciples, “My children, for me it is actually as if Mother has covered Herself with wrappers of various kinds, assumed various forms and is peeping from within them all.

“One day I was sitting and meditating on Mother in the Kali temple,” said Sri Ramakrishna. “I could by no means bring the Mother's form to my mind. What did I see then? She looked like the prostitute, Ramani, who used to come to bathe in the river, and she peeped from near the jar of worship. I saw it, laughed and said, ‘Thou hast the desire, O Mother, of becoming Ramani today. That is very good. Accept the worship today in this form.’ Acting thus, She made it clear that a prostitute also is She, there is nothing else except Her.”52

The devotee who surrenders to the Divine Mother obtains everything. Joy in life and joy in death. All becomes bliss, and all becomes play.

Kali's boon is won when man confronts or accepts her and the realities she dramatically conveys to him. The image of Kali, in a variety of ways, teaches man that pain, sorrow, decay, death, and destruction are not to be overcome or conquered by denying them or explaining them away. Pain and sorrow are woven into the texture of man's life so thoroughly that to deny them is ultimately futile and foolish. For man to realize the fullness of his being, for man to exploit his potential as a human being, he must finally accept his dimension of existence. Kali's boon is freedom, the freedom of the child to revel in the moment, and it is won only after confrontation or acceptance of death. Ramakrishna's childlike nature does not stem from his ignorance of things as they really are but from his realization of things as they really are. He is able to revel in the moment, for he knows that to live any other way is a denial of things as they are. To ignore death, to pretend that one is physically immortal, to pretend that one's ego is the center of things, is to provoke Kali's mocking laughter. To confront or accept death, on the contrary, is to realize a mode of being that can delight and revel in the play of the Gods. To accept one's mortality is to be able to act superfluously, to let go, to be able to sing, dance, and shout. To win Kali's boon is to become childlike, to be flexible, open, and naive like a child. It is to act and be like Ramakrishna, who delighted in the world as Kali's play, who acted without calculation and behaved like a fool or a child.53

Mother Kali creates when she feels like it and then again destroys her creation when she feels like it. All in fun—just like a child who spends a long time to build a sand castle with great care and, then, on the spur of the moment, destroys it with great delight.

“Bondage and liberation are both of her making,” said Sri Ramakrishna. “By her maya worldly people become entangled in lust and greed, and again, through her grace they attain their liberation. She is called the Savior, and the Remover of the bondage that binds one to the world.”

In the world's busy market-place, O Shyama, Thou art flying kites;

High up they soar on the wind of hope, held fast by maya's string.

Their frames are human skeletons, their sails of the three gunas made;

But all their curious workmanship is merely for ornament.

Upon the kite-strings Thou hast rubbed the manja-paste54 of worldliness,

So as to make each straining strand all the more sharp and strong.

Out of a hundred thousand kites, at best but one or two break free;

And Thou dost laugh and clap Thy hands, O Mother, watching them!

On favoring winds, says Ramprasad, the kites set loose will speedily

Be borne away to the Infinite, across the sea of the world.55

The Master said: “The Divine Mother is always playful and sportive. This universe is her play. She is self-willed and must always have her own way. She is full of bliss. She gives freedom only to one out of a hundred thousand.”56 That's a fairly slim chance but no reason to give up.

An ancient Hindu story tells about two men practicing spiritual disciplines under a tree. When the first man, by divine intervention, found out that he had to live two more lives before he could attain liberation, he sat down in despair. When the second was told by a divine voice that he had to be born as often as there are leaves on the tree, he began to dance with joy. “I will be liberated so soon,” he shouted. At this, the divine voice said, “My son, I have just tested you. You are liberated right now.”

We all worship God, knowingly or unknowingly. Satyam shivam sundaram—God is Truth, God is Beauty, God is Bliss. When we have removed all the noise and static, we find that it is our nature to love God—passionately. Jai Kali.

1 Sister Nivedita, Kali the Mother (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1986), p. 35.

2 Dakshina translated means an act of gift-giving, especially to a priest for performing a sacrificial ritual.

3 Followers of Tantra.

4 The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, p.135.

5 Robber's Kali.

6 Swami Harshananda, Hindu Gods and Goddesses (Mysore: Ramakrishna Ashrama, 1981), p. 147.

7 The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, p. 579.

8 Four yards of cloth wrapped around the waist.

9 Indian shirt.

10 Priest.

11 The images of male deities only are invested with the sacred thread.

12 The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, p. 271.

13 The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, p. 692.

14 The concept of the gunas is explained in Part 1.

15 Six major philosophies—samkhya, yoga, nyaya, vaishesika, mimamsa, and vedanta.

16 The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, p. 106.

17 The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, p. 345.

18 The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, p. 283.

19 Sir John Woodroffe, The Garland of Letters (Madras: Ganesh & Company, 1985), p. 237.

20 A pearl necklace of seven strings.

21 The Garland of Letters.

22 Robert Graves, The White Goddess (New York: Vintage Books, 1958), p. 250.

23 Barbara G. Walker, The Woman's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets, (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1983), p. 491.

24 A stone symbol of Vishnu; it is oval and bears certain markings—of natural formation, found in certain river beds in India.

25 A stone symbol of Shiva.

26 A wick placed into clarified butter.