CHAPTER ONE

The Culture of Collecting

ROOSEVELT’S MUSEUM

One winter day early in 1867 a frail eight-year-old boy named Theodore Roosevelt discovered a dead seal placed on exhibit outside his neighborhood market. The creature so fascinated him that he decided to start a natural history collection and convinced the storekeeper to give him the seal’s skull as his first acquisition.1 By the end of the year the “Roosevelt Museum of Natural History” contained more than a hundred additional specimens, including the nests and eggs of birds, seashells, minerals, pressed plants, and other natural objects. Through regular efforts in the field, contributions from sympathetic relatives, exchanges with other collectors, and purchases from dealers, Roosevelt continued to add to his collection over the next decade. He even convinced his parents to let him take lessons in mounting animals from the famed New York taxidermist John G. Bell. Roosevelt’s boyhood museum marked the first manifestation of a lifelong interest in natural history for this future president of the United States.

Though Roosevelt was more earnest than some of his contemporaries, his experience was hardly unique. In the second half of the nineteenth century thousands of Americans began filling their homes with an array of “choice extracts from nature.”2 Then as now, these collectors were motivated by a variety of considerations.3 The aesthetic appeal of the objects they gathered, a competitive spirit, and a curiosity about the natural world lured many Americans out into the nation’s fields and forests in search of new acquisitions. So too did a desire to cultivate self-improvement, to gain exercise, to display gentility, to increase wealth, and to escape temporarily from the confines of a modern urban existence.4 Some collectors believed that the specimens they amassed provided a way to gaze at the mind of God.5 A few even hoped to make a contribution to science.

The nineteenth-century collecting phenomenon was not something entirely new. For over three centuries a “cabinet of curiosities,” appointed with a hodgepodge of natural and fabricated objects, had served as a sign of culture and learning among the European upper classes.6 Anxious to emulate their counterparts abroad, wealthy Americans began amassing similar collections in the early eighteenth century.7 It was not until the burgeoning middle class adopted the practice in the mid-nineteenth century, however, that natural history collecting really flourished in this country.8 What began with an interest in gathering botanical specimens in the 1830s expanded dramatically in scope and scale over the next several decades, particularly in the years after the Civil War.

This unprecedented flurry of activity led to the creation of what might be described as a culture of collecting. Beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century, American collectors forged a community united not only by a shared interest in amassing natural history objects, but also through vast correspondence networks, membership in scientific societies, subscriptions to natural history periodicals, and patronage of commercial firms that catered to the natural history trade. Young and old, male and female, beginner and expert alike were all a part of this extensive and heterogeneous community in which specimens were bought, sold, traded, and admired.9

THE CULTURE OF COLLECTING

The post-Civil War growth of popular interest in natural history was firmly rooted in several fundamental social, economic, and technological changes.10 Between 1860 and 1900 the total population of the United States more than doubled, the gross national product quadrupled, and the total number of people living in urban areas increased more than five times. By 1900 more than sixteen metropolitan areas had populations in excess of a quarter million, and, excluding the South, for the first time most Americans lived in cities. During this period the nation also pushed relentlessly westward, adding twelve new states and several territories. Within the span of only two generations, America was transformed from a largely rural, agrarian nation to an urban, industrial giant.

The construction of an extensive transportation and communication infrastructure linked the expanding nation together as never before. Two key technological systems first brought into limited production in the 1840s, the railroad and the telegraph, soon provided for the rapid and reliable interchange of information, products, and people across the vast expanses of the North American continent.11 Railroads spanned a total of thirty thousand miles by 1860, and the rate of growth accelerated in the decades that followed. By 1890 mileage had increased more than fivefold, while extensive bridge construction and interindustry standardization joined the separate lines into a truly national system. The railroads not only brought the nation closer together by decreasing the time, expense, and discomfort usually associated with earlier forms of long-distance travel, they also created a model for the large-scale, vertically integrated corporations that proliferated in the years after the war.12

Other developments eased the dissemination of knowledge. In the years surrounding the war, improvements in presses, plates, paper, and typesetting machines revolutionized the publishing industry by greatly increasing printing speed while decreasing the unit cost for newspapers, periodicals, and books.13 Postal rates for printed matter, which had slowly but steadily decreased throughout the nineteenth century, dropped dramatically between 1874 and 1885, when officials introduced new second- and third-class rate schedules.14 At the same time better access to education and a boost in literacy rates resulted in a greater demand for reading material of all types.15 One consequence of these developments was what one historian has called “a mania of magazine-starting.” Within the two decades after the Civil War the total number of American periodicals jumped from seven hundred to thirty-three hundred.16

It took equally fundamental changes in attitude for these social, economic, and technological transformations to translate into a broad popular interest in natural history. Among the most important of these new sensibilities was a fresh appreciation for nature and leisure. The Europeans who first settled the New World tended to view the vast North American continent as either an evil, chaotic wasteland or a storehouse of economically valuable resources.17 In either case the reigning assumption was that God had issued a divine mandate to carve out an ordered civilization from the wilderness and to exploit nature to its fullest. But by the nineteenth century, as the process of conquering nature had reached increasingly higher levels of perfection, a backlash began to coalesce.

One early and lasting counterpoint to the predominant ethos of development and domination was a series of aesthetic, philosophical, and literary movements known collectively as Romanticism.18 These various strands began to emerge in the late eighteenth century among European intellectuals rebelling against the austere neoclassicism, mechanistic spirit, and arch-rationalism of the Enlightenment. Romantics tended to find inspiration in the imagination, the emotional, the mysterious, the primitive, and the sublime. Perhaps most importantly in this context, they also attached a new aesthetic and spiritual value to the natural world. By the early nineteenth century the naturalistic landscapes of the Hudson River School, the anthropocentric wildlife portraits of John James Audubon, and the effusive poetry of William Cullen Bryant provided evidence that Romantic currents had found their way to the New World. Although Romanticism failed to supplant the dominant utilitarian vision of nature, by the middle of the nineteenth century it had become a permanent fixture on the American cultural scene.

Transcendentalism, a peculiarly American version of Romanticism that originated in the 1830s, proved equally influential and tenacious.19 Two of Transcendentalism’s major prophets, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, argued that the means to self-renewal and self-realization was self-surrender before the altar of nature.20 For the increasing number of late-nineteenth-century Americans sympathetic to Thoreau’s dictum—“In wildness is the preservation of the world”—Transcendentalism provided a potent argument for the preservation of nature.21 Even in its more pervasive dilute forms, the new doctrine suggested regular contact with nature as an antidote for the many ills that plagued an increasingly urban and industrial America.

As the century wore on, more and more Americans embraced the Transcendentalist diagnosis and prescription.22 For some, periodic retreats into the relative wilderness of the many state and national parks established after the Civil War acted as a balm to soothe the irritations brought on by an increasingly bustling and artificial way of life.23 Others sought relief in the more secure and accessible middle grounds crafted between the extremes of nature and civilization: the landscaped urban park, the borderland suburb, and the local country club.24 Many were content to enjoy the nature experience vicariously, through a growing number of essays and books that interpreted the natural world for their readers.25 Although they pursued a variety of approaches in their quest to get “back to nature,” one thing was certain: as civilization loomed ever larger in their daily lives, many Americans experienced an almost primordial yearning to reestablish some form of contact with nature.26

Closely related to the newfound respect for nature was an increasing appreciation for leisure.27 The pious pioneers who settled the continent had elevated the toil associated with taming the American wilderness to the level of divine pursuit. Increasing secularization during the ensuing centuries may have minimized the explicitly religious connotations of this deeply ingrained work ethic, but it did little to diminish its hold on the growing middle class; early nineteenth-century European visitors, accustomed to a much more measured pace of life, constantly marveled at the “franticness and busyness” of Americans.28 Not until the middle decades of the century did the gospel of work finally began to relinquish its stern grip as Americans at last “learned to play.” A slow but steady decline in the average workweek was paralleled by a robust expansion in the number of leisure opportunities, including bicycling, picnicking, camping, amusement parks, and a host of new participant and spectator sports, to name just a few.29 Yet as historian Daniel Rodgers has pointed out, most middle-class Americans continued to reject outright idleness or repose. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, the leisure activities pursued were frequently as “energetic as work itself’ and usually imbued with a higher purpose.30

Collecting was an appropriately purposeful pastime that the American and British middle class increasingly pursued with zeal.31 With unprecedented enthusiasm, Victorians on both sides of the Atlantic rushed to fill their homes with a bewildering array of objects, ranging from coins, stamps, and curios to ferns, figurines, and photographs.32 The middle-class collecting craze was already so prevalent by 1868 that Charles Eastlake’s Hints on Household Taste entered a futile protest against the trend of displaying “too many knick-knacks” on “too many ‘what-nots.’”33

Few, if any, heeded Eastlake’s advice. Rather, most commentators emphasized the benefits of collecting and strongly encouraged the practice. Among the most vigorous proponents of the collecting urge was John Edward Gray, keeper of the zoological cabinet at the British Museum and author of one of the first manuals for stamp collectors, published in 1862. According to Gray: “The use and charm of collecting any kind of object is to educate the mind and the eye to careful observation, accurate comparison, and just reasoning on the differences and likenesses which they present, and to interest the collector in the design or art shown in the creation and manufacture, and the history of the country which produces or uses the objects collected.”34

Many argued that amassing natural history specimens—minerals, pressed plants, insects, shells, stuffed birds, and eggs—was even more edifying than collecting artificial objects like stamps and coins. The American pastor and educator E. C. Mitchell urged parents to encourage their children to take up the practice at a tender age. The experience thereby gained would lead to an appreciation of “the works of God in nature,” stimulate the mind, and arouse an “active enthusiasm” for the process of learning. To those who dared complain about the space taken up by collections, Mitchell replied: “almost any house can afford to spare the child a few shelves, or a home-made box or cabinet. And it will help to train and systemize the child’s mind, to feel that he has a place of his own, where he can keep his treasures, and for the good order of which he is responsible.”35 Others echoed Mitchell’s enthusiasm for natural history, arguing that the collector was afforded “not only pleasure, but study, a love of the great and glorious things, recreation, exercise and the promoter of all things which tend to make nobler manhood and womanhood.”36 One devotee even claimed that collecting natural objects cultivated the powers of discernment and careful observation necessary for a successful business career.37 Whether they accepted all the arguments of its advocates, Americans with a vague longing for nature and a new appreciation for leisure turned to natural history collecting with increasing frequency in the second half of the nineteenth century.

QUANTITATIVE DIMENSIONS

What began as a limited expansion of popular interest in natural history before the Civil War exploded in the decades following the truce at Appomattox. While it is impossible to measure the precise dimensions of this pervasive activity, some appreciation for the conspicuous postwar growth of the culture of collecting can be gained by examining changes in some of its individual components.

The closest thing we have to a direct measure of the surge in the number of collectors is the various editions of The Naturalists’ Directory, first published in 1865.38 The initial edition, compiled by former Agassiz student Frederic Ward Putnam, contained the names, addresses, and fields of specialty for more than four hundred naturalists, most of whom were collectors.39 The appearance of a published listing of American naturalists suggests that the collecting community had reached an important milestone. More striking still is the growth in the number of entries in subsequent editions of the work. The number of naturalists recorded in the edition Putnam published only one year later increased almost four times, to nearly sixteen hundred.40 By 1879 the number of entries more than doubled again, to nearly thirty-three hundred, before peaking at nearly six thousand in the early 1890s.41 While yearly variations in the size of the Directory might reflect the editor’s earnestness in soliciting names, the general trend was one of vigorous growth. Yet the listing can hardly be taken as comprehensive, for only the most committed collectors would have bothered submitting their names.

The creation of scientific societies devoted to natural history provides another indication of its increasing appeal. As historian Ralph Bates’s study demonstrates, by 1865 there were only 36 active scientific societies in the United States.42 For many of these institutions the collection, preservation, and description of natural objects provided a major focus. However, after the war the numbers quickly mounted. According to lists published in The Naturalists’ Directory, by 1878 there were 141 local and state societies that concentrated on some form of natural history, and by 1884 that number had grown to more than 200.43

Even more impressive is the rise of a new kind of natural history society aimed primarily at youth. Named after the charismatic naturalist and popular icon Louis Agassiz, the Agassiz Association began modestly.44 Harlan H. Ballard, a school administrator from Lenox, Massachusetts, organized the first chapter in 1875 to encourage his students to “collect, study, and preserve natural objects.”45 Five years later Ballard began calling for other interested parties across America to create local chapters. The response was overwhelming, and by 1884 collecting enthusiasts had established more than six hundred local chapters of the Agassiz Association with a total of over seven thousand members.46 Thirteen years later Ballard claimed a cumulative total of twelve hundred chapters and twenty thousand members, which, according to one observer, were united with the single purpose of “exchanging specimens and corresponding with one another on matters of common interest.”47

In 1882 Ballard issued the first of four editions of his Agassiz Association handbook. Ballard designed his brief introduction to the world of natural history collecting to supplement a regular Agassiz Association department in St. Nicholas Magazine and a short-lived attempt to initiate an independent publication for the organization, The Swiss Cross (1887-1889).48 Though compact, Ballard’s handbooks were brimming with practical advice on organizing association chapters; building proper storage cabinets; procuring natural history books; and (most importantly) collecting, preserving, buying, and exchanging a variety of specimens, ranging from pressed plants, seaweed, minerals, and insects, to bird skins and eggs.

Around the turn of the century a broader initiative aimed specifically at children began to eclipse Ballard’s activities. Nature study was a pedagogical reform movement dedicated to the proposition that children needed regular, firsthand exposure to the natural world.49 Some advocates, like the biologist Clifton F. Hodge, believed that nature study might shield urban youth against “idleness and waste of time, evil and temptation of every sort”; others, like the horticulturalist Liberty Hyde Bailey, hoped the reform might help stem the population drain from rural areas.50 Whatever their concerns, in 1905 proponents of the idea began publishing Nature Study Review to promote the initiative, and three years later they organized the American Nature Study Society.51 In 1911 Anna Botsford Comstock, one of the founders of the movement, published her seminal Handbook of Nature Study, a widely adopted textbook that went through twenty-four editions and remains in print today.52

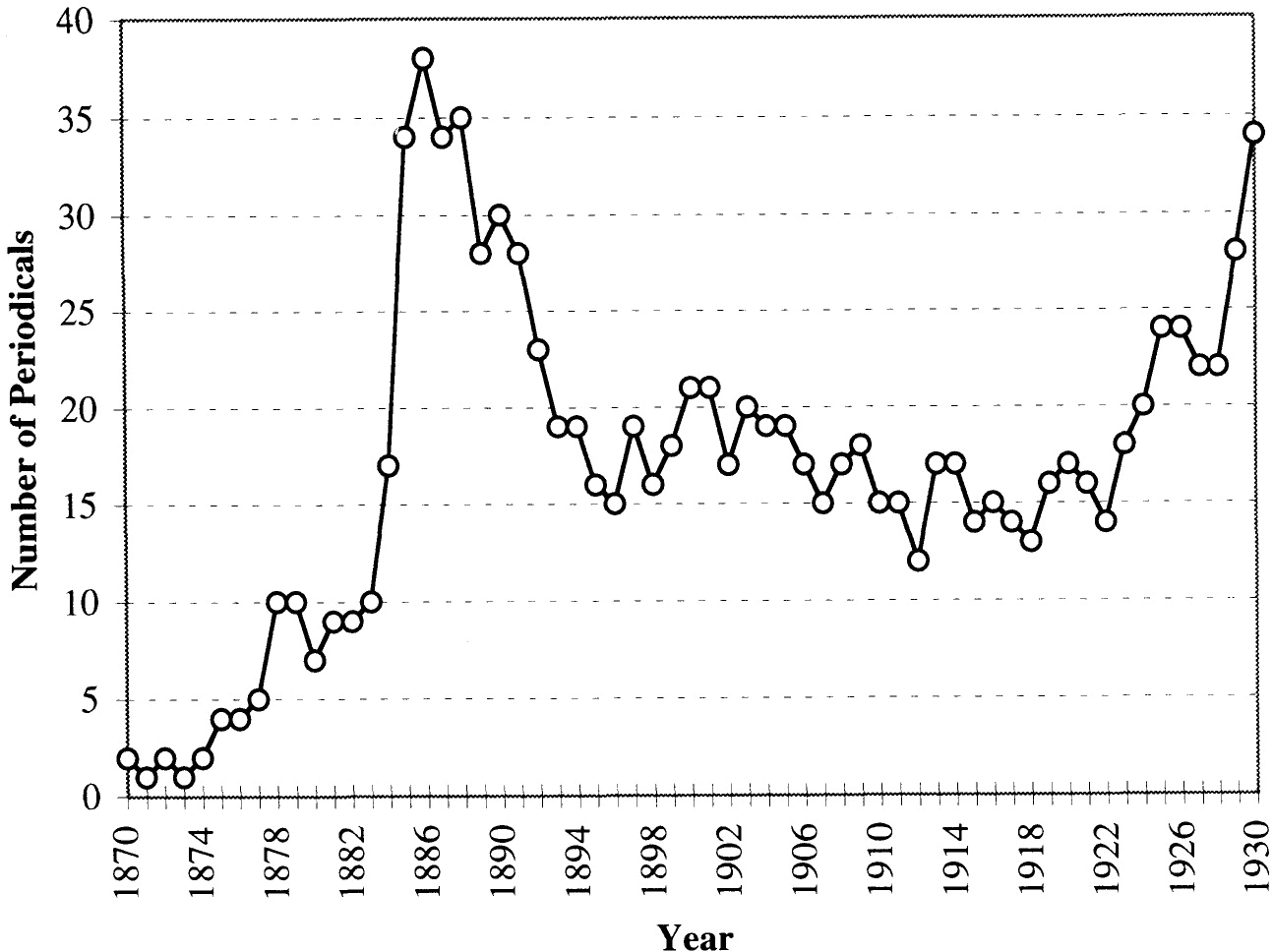

An examination of trends in periodical publication provides additional evidence of the groundswell of popular interest in natural history during the second half of the nineteenth century.53 A count based on three extensive bibliographies of “minor” natural history periodicals published during this period reveals modest beginnings in the mid-1870s, when only a handful were issued in any given year.54 Improved printing technologies, reduced postal rates, and mounting public interest promoted a tremendous growth in natural history journals in the early 1880s (fig. 1). By 1886 nearly forty such periodicals were available. This was followed by a precipitous decline due to market saturation, the depression of 1893, and more rigid enforcement of postal regulations. For the next three decades the number of natural history periodicals remained relatively constant, before increasing again in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Figure 1. Minor natural history periodicals published in the United States and Canada, 1870-1930. Compiled from Burns, “Bibliography of Scarce or Out of Print North American Amateur and Trade Periodicals”; Fox, “American Journals Omitted from Bolton’s ‘Catalog’”; and Underwood, Bibliography of North American Minor Natural History Periodicals.

Until the end of the nineteenth century, dealers issued many of these periodicals, which were often little more than thinly veiled advertisements for their wares (fig. 2). Local postmasters occasionally followed the letter of postal regulations and refused to grant second-class rates to publications that failed to be issued at some regular stated interval, lacked a legitimate subscription list, or were not “devoted to literature, the sciences, arts, or some special industry.”55 For example, in 1890 Charles H. Prince was denied second-class rates for his newly created The Oologist’s Advertiser. But like many other publishers in the same predicament, Prince simply changed the name of his periodical to The Collectors’ Monthly and successfully reapplied for preferential rates.56 Increasingly impatient with flagrant abuses of the system, in 1901 the postmaster general began systematically revoking the second-class privilege from suspect publications.57 Among the casualties of this enforcement campaign were American Ornithology for the Home and School and The Atlantic Slope Naturalist.58

Figure 2. Cover of Random Notes on Natural History (1884). This short-lived trade journal, published by the natural history firm Southwick and Jencks, had a beautifully illustrated cover and an unusually frank title.

Many of the dozens of natural history periodicals established in the second half of the nineteenth century enjoyed healthy circulations, if not long lives.59 For example, the American Magazine of Natural Science (1892-1894) and The Owl (1886-1888) each claimed a circulation of two thousand.60 The Hoosier Naturalist (1885-1888), The Spy Glass: A Magazine for Collectors (1888), and The Young Oologist (1885) boasted a regular readership of five thousand. And the Naturalists' Leisure Hour and Monthly Bulletin (1887-1893) reported seven thousand subscribers.

More striking are the figures for special issues, which were distributed widely in an attempt to gain new subscribers and to publicize the businesses that sponsored them. For example, in 1883 Henry A. Ward distributed sixteen thousand copies of his Natural Science Bulletin.61 During the next two years the owner of the Ornithologist and Oologist, Frank Blake Webster, issued nearly forty thousand copies of his periodical.62 And at the height of his business in 1893, Frank H. Lattin passed out over twenty thousand copies of a single issue of the Oologist.63

The publishers responsible for these last three periodicals were all natural history dealers, who provide a final indicator of the growth of popular interest in collecting. Local taxidermy shops, which had long served as gathering places for area naturalists and frequently offered natural history specimens for sale, were early manifestations of these enterprises. With the growth of popular interest in natural history and the increasing ease of transacting business across the nation, many commercial establishments began cultivating a more national clientele for their specimens, supplies, and publications. During the last several decades of the nineteenth century, more than one hundred enterprising naturalists established American businesses to promote and profit from the broad popular enthusiasm for amassing natural history specimens.64

COLLECTING CONFLICTS

Although members of the diverse community of collectors existed together amicably for much of the second half of the nineteenth century, the potential for conflict was always present. One of several unresolved tensions was between the entrepreneurial and Romantic impulses that informed the desire to amass and display natural objects.65 The establishment of numerous businesses devoted to the sale of natural history specimens (fig. 3) tended to reinforce the idea that nature was a resource or commodity, existing solely for human ends. For example, the wide distribution of natural history dealers’ catalogs undoubtedly influenced the ornithologist Elliott Coues to declare in his best-selling collecting manual of 1874: “How many examples of the same bird do you want?—All you can get. . . . Bird skins are capital.”66 Support for the idea of human domination of nature even found expression in the very act of collecting itself. After all, those tidy cabinets of specimens were composed of the lifeless remnants of once autonomous beings that were removed from their natural context and reordered according to the whims of collectors.67

Romanticism confounded the economic calculus that undergirded the commodification of nature and even challenged the legitimacy of the idea of human domination of the natural world. Certainly the Romantic sensibility alerted collectors to discover beauty in the natural objects around them and was one of the major factors leading to the large-scale growth of natural history collecting. But Romanticism also suggested that our interactions with nature were imbued with a spiritual dimension that defied economic valuation. For some followers the doctrine even implied that humans ought to be kinder and gentler in their dealings with the natural world. The fundamental tension between these opposing conceptions of nature remained largely unarticulated until rise of the Audubon movement and the growth of popular interest in birdwatching at the turn of the century.

A second cleavage point within the culture of collecting existed between expert naturalists whose central commitment was to the production of scientific knowledge and the much larger number of collectors for whom the collection itself was often an end. As the century progressed, scientific naturalists became increasingly impatient with dealers and collectors who failed to record the proper data with the specimens they gathered, who eschewed scientific nomenclature, or who stubbornly refused to acknowledge the authority of experts. These and other tensions would later provoke a schism in the culture of collecting. For much of the second half of the nineteenth century, however, members of the collecting community managed to gloss over their differences in motivation, ability, and level of commitment. Exactly how this was negotiated within one subset of the culture of collecting, the ornithological community, is the subject of the next chapter.