CHAPTER TWO

Desiderata: Bird Collecting and Community

RECRUITING RIDGWAY

While sorting through his mail in the spring of 1864, Smithsonian Assistant Secretary Spencer Fullerton Baird found a letter that caught his eye. It was from Robert Ridgway, a fourteen-year-old boy from Mt. Carmel, Illinois, who wanted to know the name of a bird he and two of his friends had discovered on one of their recent forays into the woods.1 Accompanying the letter was a carefully rendered color portrait of the bird in question. Always eager to recruit young naturalists to join his extensive collecting network, Baird identified the bird as a purple finch, complimented Ridgway on his “unusual degree of ability as an artist,” forwarded a copy of the Smithsonian circular on collecting specimens, and suggested he use scientific rather than local names of birds in future correspondence. Like he had done many times before, Baird closed his reply with an offer to help the young lad in any way he could.2 As Ridgway revealed in a moving letter the next year, Baird was the first person to encourage his interest in birds:

I am a poor boy; the oldest of a family of seven children; my father is the junior partner in a drug-store, the slim proceeds of which are scarcely enough to supply us with the necessaries [sic] of life. In all my labors and studies I have had to support myself—or supply myself with material for drawing &c, which I can just barely do by result of a small capital invested in the drug-store and which at first amounted to only 20 ets. My parents do not fully understand my views and motives and consequently I do not expect to receive that encouragement which I would expect to receive from them. My mother is willing to do a good part for me, but my father says that my study and drawing is more expensive than beneficial and calls it mere child’s play. To you therefore,—as my only friend except my parents, do I go for counsel.3

The connection with Baird proved to be a turning point in Ridgway’s life. At Baird’s constant urging, over the next few years he mailed a regular supply of descriptions, drawings, eggs, and crudely prepared skins to the Smithsonian.4 When Ridgway turned seventeen, Baird invited him to Washington, taught him how to make proper bird skins, and arranged for him to serve as a collector on Clarence King’s United States Geographical Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel. After two successful seasons exploring the Great Basin region in the West, Baird hired his young protégé to complete the technical descriptions and drawings for his three-volume History of North American Birds: Land Birds (1874).5 He also convinced the book’s publisher to pay Ridgway a regular salary until he could secure the funds to retain him as a curator of ornithology at the Smithsonian in 1874.6 Under Baird’s tutelage, Ridgway soon became proficient in the finer points of technical ornithology and, like his mentor, became an accomplished “collector of collectors.”7

The Baird-Ridgway relationship was unique only in the prominence of the individuals involved. During the second half of the nineteenth century experienced ornithologists routinely nurtured the efforts of other collectors. They did so by publishing detailed guides on how to collect, preserve, and identify birds as well as by recruiting neophytes for their expansive collecting networks. Those networks typically included not only beginning bird enthusiasts, but also a variety of more advanced collectors, dealers, taxidermists, sport hunters, and scientists. Until the end of the century these diverse elements formed an extended ornithological community united by a common interest in amassing North American birds and their eggs.

Middle-class Americans with more leisure time on their hands turned to bird collecting for many of the same reasons they began to amass other natural history objects: a desire to escape, however fleetingly, from an increasingly urban and industrial America, to test one’s mettle against the elements, and to return with the aesthetically pleasing specimens that found a prominent place in many Victorian homes (fig. 4). Of course, collectors could simply purchase desirable specimens from the dozens of taxidermy and natural history establishments that proliferated in the second half of the nineteenth century. But for many the experience of collecting itself provided much of the activity’s allure. As Spencer Trotter, a prominent Philadelphia ornithologist, asked: “What branch of science comes nearer to satisfying the primitive instinct that takes him into the woods to hunt and fish or for the mere sake of steeping the senses in the fresh, rank life of things, and at the same time abundantly satisfying the acquisitive and classifying habit of mind?”8 And as Trotter hinted, the tools, methods, motivations, and sometimes even the intended object of bird collecting also bore a striking resemblance to another increasingly popular middle-class activity: game hunting.

The individuals who comprised the extended ornithological community were firmly united by a common desire to possess specimens of North American birds and eggs. For some, these specimens were little more than objects to be carefully amassed and proudly displayed; for others, they were primarily commodities to be bought, sold, and traded; and for a relative few, they were the raw material for research into the taxonomic relationships and geographical distribution of North American avifauna. Despite the diverse and often mixed motivations of most individual collectors, for much of the second half of the nineteenth century the specimen itself provided the glue that held together the extended ornithological community.

Figure 4. Collectors gathering “rare birds and eggs” in Florida, 1888.

EARLY AMERICAN COLLECTIONS

Although naturalists had amassed bird collections for ages, not until the middle decades of the eighteenth century did they finally devise effective procedures to protect specimens from the ravages of decay and insects. As historian Paul Farber has shown, these techniques remained controversial or shrouded in secrecy for decades following their initial discovery, but by the early nineteenth century, the use of various arsenic preparations became a standard method to preserve bird skins.9 Simpler procedures for preserving eggs—by blowing out the contents through small holes made at each end—appear to have been developed at about the same time.10 These preservation techniques did not entirely solve the problem of decay and insect infestation—curators still had to remain vigilant—but they nonetheless became a major factor in the establishment of extensive, stable ornithological collections at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries.11

Charles Willson Peale pioneered preservation and taxidermy techniques in this country at the end of the eighteenth century, and Peale’s Philadelphia Museum, established in 1786, contained the largest and most important American ornithological collection of its day.12 Stocked with specimens gathered by himself, his sons, and other naturalists, Peale’s private establishment included most North American bird species known during this period. An 1805 catalog claimed that the bird collection exceeded 760 specimens.13 Among the most prominent of the many contributors to and users of the Peale collection were Alexander Wilson, author of the nine-volume American Ornithology (1808-1814), and Charles Lucien Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon, who completed a four-volume supplement to Wilson’s work (1825-1834).14

Following the standard museum practice of his day, Peale invariably mounted his specimens for exhibit. But unlike his colleagues here and abroad, Peale not only succeeded in placing his birds in lifelike attitudes, he also displayed them in cases with painted landscape backgrounds intended to represent the native environment of the species. Peale’s bird displays thus became early, primitive examples of the habitat exhibits perfected in the second half of the nineteenth century.15 Although Peale’s Philadelphia Museum was disbursed in 1850, examples of his taxidermic technique survive to this day in the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard.16

Another Philadelphia institution, the Academy of Natural Sciences, also established an early and important ornithological collection in the United States. Immediately after its founding in 1812 the organization began amassing specimens for its museum.17 Following the election of William Maclure as president in 1817, the academy started a periodical and a more active accession program. Through purchase, exchange, and donation, the academy’s collection greatly increased under Maclure’s twenty-three-year reign. By 1840 the ornithological collection alone numbered around thirteen hundred specimens.18

Even more impressive growth came just a few years later when Thomas B. Wilson placed his extensive private bird collection on permanent deposit at the academy.19 Although trained as a physician, Wilson never practiced medicine. Instead he devoted himself to amassing natural history specimens, especially insects, birds, and rocks. Besides mounting expeditions throughout much of the eastern United States and portions of Canada, Wilson traveled to Europe to purchase the extensive collection of Prince Massena d’Essling, Duc de Rivoli (which alone contained at least ten thousand mounted specimens and five thousand species), the John Gould type collection of Australian birds, the Captain Boys Indian collection, and others. Following Wilson’s acquisitions, Philip Lutley Sclater, secretary of the Zoological Society of London, pronounced the academy’s collection “probably superior to every Museum in Europe and therefore the most perfect in existence.”20

With Wilson’s contributions, the academy’s ornithological collection was not only the largest in North America, it was also one of the few with an extensive series of non-North American birds. Its curator, the Philadelphia merchant and publisher John Cassin, became one of only a handful of U.S. ornithologists from this period to become an authority on foreign birds.21 Cassin attracted no protégé, and when he died in 1869 the collection languished for nearly two decades.22

After an aborted attempt at establishing a society devoted to natural history a few years after the founding of the Academy of Natural Sciences, in 1830 New England naturalists organized a more enduring organization, the Boston Society of Natural History.23 With miscellaneous donations from explorers, naturalists, missionaries, and sea captains, the society’s collection quickly grew in size and diversity. By 1840 the ornithological collection alone numbered 475 specimens, and by ten years later it had surpassed the 1,200 mark.24 In 1849 the organization established a separate department of oology, which was placed under the direction of the Boston physician and publisher Thomas M. Brewer. The Boston Society ornithological collection continued to grow slowly until 1865, when curator Henry Bryant donated the collection of Count Lafresnaye de Falaise. This important acquisition contained 8,656 mounted specimens representing some 4,000 species and many types. Like the Rivoli collection, it consisted largely of non-North American species.25

Other institutions and individuals in the United States initiated important ornithological collections in the first half of the nineteenth century. Several colleges, scientific societies, state natural history surveys, and entrepreneurs gathered birds and eggs for exhibit and (less often) study.26 In addition, a handful of individual naturalists—like John James Audubon, Spencer Fullerton Baird, George N. Lawrence, John Cassin, and John Kirk Townsend—amassed extensive private collections during this period to conduct research and provide material for others.27 But compared to what came in the second half of the nineteenth century, the scale of this collecting activity remained limited and the ornithological community remained relatively small and undifferentiated from the larger natural history community.

COLLECTING NETWORKS

The establishment of extensive collecting networks was one of a series of developments that signaled a fundamental turning point in the scope and scale of American natural history collecting more generally and bird collecting in particular. Louis Agassiz began one of the first and largest of these networks shortly after his arrival on American shores in 1846. One year later he decided to accept a professorship of natural history and geology at Harvard, a position created for him when the Lawrence Scientific School was organized.28 From the start the flamboyant Swiss naturalist captivated the American public while cultivating a broad popular interest in natural history. Agassiz’s devotion to popularization was at least partially self-interested; he quickly discovered that an enlightened public was the best means to insure a steady supply of specimens and funds for his ambitious publication, research, and museum-building agenda.

Agassiz regularly solicited specimen donations through printed circulars broadcast to a wide segment of the American natural history community.29 The response was overwhelming. The regular stream of specimens sent in by Agassiz’s extensive network of collectors, gathered by his growing staff of student assistants, and purchased from European sources quickly overwhelmed the series of temporary structures housing the burgeoning museum. With a job offer for the prestigious National Museum of Natural History in France in hand as a bargaining chip, Agassiz finally raised the funds needed to build a large, permanent structure, the Museum of Comparative Zoology, which he hoped would soon rival the great European natural history institutions. In 1860 alone, when the first of what were eventually to become several wings of the new building was occupied, donations and purchases added ninety-one thousand specimens to the MCZ collection.30 To answer critics of his seemingly insatiable appetite for specimens and funds, Agassiz resorted to a biological analogy: “it is with museums as with all living things; what has vitality must grow. When museums cease to grow, and consequently to demand ever-increasing means, their usefulness is on the decline.”31

Although Agassiz’s ostensible policy was to avoid collecting in areas already well represented in existing American museums, several of his student assistants began amassing extensive bird skin, skeleton, and alcoholic collections for the MCZ.32 For example, Addison E. Verrill came to Harvard in 1859 with a keen interest in birds and, at Agassiz’s suggestion, began gathering a collection of sea-bird embryos before turning to the study of marine invertebrates. Three years later, J. A. Allen, whose curiosity about birds was more enduring, arrived in Cambridge to study under Agassiz.

Allen had begun collecting natural history specimens while a young teenager on his family’s farm in Springfield, Massachusetts.33 In the winter of 1862 he enrolled as a special student under Agassiz with the proceeds from the sale of his prized collection of mounted birds.34 After his first term, Allen began cataloging the small MCZ bird collection, which at the time consisted of “several hundred skins (possibly a thousand or two, all North America), and several thousand alcoholics.”35 When Verrill left to join the faculty at Yale in 1864, Allen became principle curator of the MCZ’s bird and mammal collections. Taking his cue from his mentor, over the next two decades Allen issued regular pleas for specimen donations, purchased birds from natural history dealers, and exchanged duplicates with a network of collectors. He also collected extensively himself in Massachusetts (1862-63), New York (1864), Brazil (1865), the Midwest (1867), Florida (1868-69), the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains (1871-72), and Yellowstone (187 3).36 Because of his efforts, by 1869 the MCZ bird collection numbered twenty thousand, including six thousand specimens preserved in alcohol.37 When Allen finally left for the American Museum of Natural History in 1885, the MCZ catalog contained entries for over thirty-three thousand birds.38

While Agassiz and his student assistants were building the MCZ into an internationally renowned research museum, Agassiz’s principal rival, Spencer Fullerton Baird, was assembling his own impressive collection in Washington, D.C. Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry hired the Dickinson College professor to be his assistant in 1850.39 Although he had numerous official duties, including administering the Smithsonian’s publication and international exchange programs, Baird’s overriding interest was building a world-class natural history collection. His own personal natural history cabinet, one of the largest in the nation at the time, required two boxcars to transport to Washington and became the nucleus for what eventually became known as the United States National Museum. Upon his arrival Baird immediately set to work to expand the collection. With little available money to purchase specimens outright, Baird worked feverishly to construct one of the most extensive collecting networks ever created.

Through widely broadcast printed directions for gathering, preserving, and transporting specimens, persuasive letters to would-be collectors, encouraging follow-up letters to those who sent in material, and carefully cultivated connections with high-ranking government and military officials, Baird charmed, cajoled, and otherwise coaxed an impressive number of Americans into providing the national collection with material. Soldiers stationed at distant military outposts and individuals attached to the trans-Mississippi exploring expeditions proved a particularly fruitful source of new specimens.40 Baird in turn provided his collectors, who were often lonely and far removed from civilization, with encouragement, published acknowledgments, advice, Smithsonian publications, collecting supplies, specimen identifications, money, social contact, and the potential to have new species named in their honor.41 The product of this fruitful collaboration was a national collection that was constantly pushing at the seams. What had been six thousand specimens when Baird arrived in 1850 numbered several hundred thousand when he became secretary of the Smithsonian twenty-eight years later.42

The growth of the national ornithological collection mirrored that of the Smithsonian as a whole. The bird collection began in 1850 with Baird’s private cabinet, containing 3,696 specimens, the vast majority of which were North American birds.43 During the 1850s important acquisitions came from the series of government-sponsored western explorations and boundary surveys as well as the specimens previously gathered by the U.S. Exploring Expedition (1838-1842).44 By the end of 1860 the number of entries in the bird department’s catalog reached 20,785; by the end of 1870, 61,145; and by the end of 1880, 81,434.45

Although larger than most, Baird’s collecting network was only one of hundreds of similar, interlocking networks established in the middle decades of the century. To maintain a continued supply of new specimens for their cabinets, most serious bird collectors during this period remained in regular contact with an array of collectors, hunters, taxidermists, dealers, and scientists. George A. Boardman, a frequent Baird correspondent, provides a typical example. Boardman was a lumber-mill owner from Calais, Maine, who began collecting birds around 1840, following a business trip to South America and the West Indies.46 Impressed by the striking flora and fauna he encountered during his trip, Boardman started gathering examples of local birds and mammals to learn more about the creatures inhabiting his native Maine. Boardman’s collection grew slowly until he abandoned active management of his lumber operation in the late 1850s and early 1860s.

During the next few years Boardman devoted increasing time to his collection, which he augmented by field work in places as far away as Florida and Minnesota; extensive exchanges with naturalists across the nation; and purchases from taxidermists, dealers, game markets, and local gunners who knew he was always on the lookout for unusual specimens.47 One of his many regular correspondents, Dr. William Wood of East Winsor Hill, Connecticut, opened the first of a series of letters to Boardman with a statement exemplifying the expectation that a fellow collector would be eager to trade specimens: “My object is to open an exchange with you of skins and eggs and I trust I need make no apology for addressing one engaged in the same pursuit as myself.”48 In 1863, when Boardman’s growing collection of mounted birds became so large that it no longer fit into the glass cases installed in his house, he built a sixteen-by-twenty-foot museum for it. At the time of his death in 1901, the Boardman collection numbered some twenty-five hundred specimens.

SERIAL COLLECTING

Other private collections reached much more ambitious proportions. Access to extensive networks of collectors and dealers helped drive the trend toward larger and larger collections. Also important were new research concerns: an interest in geographical distribution that began at the time Baird and Agassiz were establishing their museums, and the new appreciation of variation initiated by the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859).49 Before these developments, collectors generally aimed to acquire a mounted pair of each species or, in the case of eggs, a single clutch. But beginning in the middle of the century, bird and egg collectors sought out increasingly larger series of each species to document its distribution and variation. The advice of Coues’s best-selling guide to ornithology (first published in 1874) strikingly reflects this new emphasis on serial collecting:

How many Birds of the Same Kind do you want?—All you can get—with some reasonable limitations; say fifty or a hundred of any but the most abundant and widely diffused species. You may often be provoked with your friend for speaking of some bird he shot, but did not bring you, because, he says, “Why you’ve got one like that!” This is just as reasonable as to suppose that because you have got one dollar you would not like to have another. Birdskins are capital; capital unemployed may be useless but can never be worthless. Birdskins are a medium of exchange among ornithologists the world, over; they represent value—money value and scientific value. If you have more of one kind than you can use[,] exchange with some one for species you lack; both parties to the transaction are equally benefited. . . . Your own “series” of skins of any species is incomplete until it contains at least one example of each sex, of every normal state of plumage, and every normal transition state of plumage, and further illustrates at least the principal abnormal variations in size, form and color to which the species may be subject; I will even add that every different faunal area the bird is known to inhabit should be represented by a specimen, particularly if there be anything unusual in the geographical distribution of the species.50

Under the mandate to amass series, North American bird collections expanded rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century. Private collections of several thousand birds became increasingly common. Particularly ambitious collectors—like James Fleming of Ontario, Max Peet of Ann Arbor, Michigan, Outram Bangs of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and John Thayer of Lancaster, Massachusetts—gathered as many as twenty-five thousand or more specimens through purchase from dealers, sponsored expeditions, exchanges with individuals and institutions, and their own field work.51

Several active collectors broke the forty thousand mark. William Brewster (fig. 5), a founder of the Nuttall Ornithological Club (1873) and the American Ornithologists’ Union (1883), began collecting birds and eggs in the area around Cambridge, Massachusetts, at the age of ten. The product of a wealthy banking family, Brewster arranged to devote his entire time to ornithology by his twentieth birthday. Five years later, in a survey of Smithsonian correspondents undertaken by Baird, Brewster listed his occupation as “amateur ornithologist” and indicated that his collection numbered some five hundred mounted specimens, three thousand skins, and approximately a thousand eggs of North American birds.52 At the time of his death in 1919, Brewster bequeathed well over forty thousand specimens to the MCZ, where he had served as honorary curator since Allen’s departure in 18 85.53 The large body of surviving correspondence generated while Brewster was amassing his collection reveals how much he relied on an extended community of amateur and professional collectors, dealers, taxidermists, scientists, and others to bring together one of the three or four largest private collections of North American birds ever assembled.54

Louis B. Bishop of New Haven, Connecticut, also began collecting birds at a young age.55 His early casual interest in birds became more serious by the age of twelve, when he and his schoolmate, Leonard C. Sanford, met an older Yale student who taught them how to skin and mount the birds they killed with their slingshots.56 Two years later Bishop received his first gun. After graduating from Yale College (1886) and Medical School (1888), he continued medical studies in the United States and abroad before returning to New Haven to practice medicine. Bishop was able to pursue his lasting enthusiasm for ornithology only during his spare moments until he retired from medicine in 1908. By the time he sold his collection to the Field Museum in 1939, he had amassed over fifty-three thousand bird skins.

In the 1890s Bishop met another physician-collector, Jonathan Dwight of New York City. The two soon developed an intense but friendly rivalry. Dwight had begun amassing eggs at age fourteen. When he enrolled in Harvard in 1876, he came under the influence of the young men who had recently organized the Nuttall Ornithological Club and soon began collecting skins. After earning his bachelor’s degree, he spent several years working for his father’s engineering firm before entering Columbia University Medical School, where he graduated in 1893. During his spare hours Dwight continued to build up his collection while publishing a series of important papers on the sequence of plumage molts in birds.57 At the time of his death in 1929, Dwight’s collection of sixty-five thousand “carefully labelled and catalogued” skins went to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where it had long been on deposit.

Figure 5. William Brewster, reclining with his collecting pistol, ca. 1890. Brewster was a leading light in the development of American ornithology but never held a professional position.

Under the mandate to amass series, egg collections could reach equally prodigious proportions. In 1883, at the time of his appointment as an honorary curator of ornithology at the Smithsonian Institution, Charles E. Bendire’s collection contained 8,000 North American birds’ eggs.58 In 1894 J. Parker Norris, Sr., and J. Parker Norris, Jr., a father and son collecting team from Philadelphia, claimed to have gathered an extensive oological collection consisting of 573 North American species, more than 5,000 sets, and 20,000 eggs.59 In 1901 John Lewis Childs, a wealthy egg collector and nursery owner in Floral Park, New York (on Long Island), purchased a single collection of over 30,000 eggs.60 He continued to add to his collection until his death in 1921. And in 1925 Richard M. Barnes, a Chicago lawyer and long-time editor of The Oologist, donated 38,721 North American birds’ eggs to the Field Museum, where he had long served as assistant curator of oology.61

SPORTING NATURALISTS

In addition to its connection with scientists and scientific institutions, bird collecting was also intimately related to the age-old practice of game hunting. Well into the second half of the nineteenth century, the two activities remained so closely related that the scientist Charles Batchelder declared that there was not “much of a dividing line between ornithologists and sportsmen.”62 John Cassin, who had made the same comparison much earlier, considered bird collecting to represent the pinnacle of field sports, an opinion that was widely shared:

Bird collecting is the ultimate refinement—the ne plus ultra of all the sports of the field. It is attended with all the excitement, and requires all the skill of other shooting, with a much higher degree of theoretical information and consequent gratification in its exercises. . . . Personal activity, coolness, steadiness of hand, quickness of eye and ear will be of service, and some of them indispensable, to successful collecting. . . . Great is the life of the woods, say we, and the greatest of all sports is bird collecting.63

Beyond supplying an important source of food for American settlers, from the beginning hunting also had more ritualistic and recreational dimensions.64 The activity provided an opportunity to join with friends in the outdoors, to leave behind cares and worries in single-minded pursuit of game. By the first half of the nineteenth century, the sporting side of hunting was increasingly emphasized, and certain attributes became expected of every gentleman hunter: intimate knowledge of the life and habitat of his quarry, skill with a gun, the ability to train and use dogs, and a well-developed sense of fair play.65

As early as 1783, the anonymously published Sportsman's Companion had begun to codify the body of knowledge and values associated with sport hunting.66 By the mid-nineteenth century, a steady stream of publications, like Elisha J. Lewis’s Hints to Sportsmen (1851) and Frank Forester’s The Complete Manual for Young Sportsmen (1856), counseled the growing number of American recreational hunters on the techniques and social graces associated with the pursuit of game.67

By the 1870s sport hunting really took off in the United States. During the first few years of that decade the number of North American organizations devoted to sport hunting tripled to just over three hundred.68 In addition, several nationally circulated periodicals, like American Sportsman (1871), Forest and Stream (1873), and Field and Stream (1874), began publication. These periodicals not only provided recreational hunters with a greater sense of identity and community, they also furnished naturalists with publication outlets.69 The most important and long-lived of these new sporting periodicals was Forest and Stream, started by the sportsman, author, and editor, Charles Hallock.70 In announcing the new periodical to George Boardman in 1873, Hallock indicated that he aimed to “make it the standard authority and work of reference on sporting matters and topics of natural history.”71

Taxidermy provided another point of intersection between the closely related activities of game hunting and bird collecting. Sport hunters often wanted their prized takes shaped into permanent trophies to decorate their homes and offices with proof of their prowess. Sometimes they tried to mount skins themselves, with the aid of published guides like William Bullock’s handbook (1st American ed., 1839) and Lewis’s Hints to Sportsmen.72 But more often than not they relied on professional taxidermists, whose establishments became more commonplace with the increase in sport hunting.

John G. Bell, who had accompanied Audubon during his expedition to the upper Missouri in 1843, owned one of the most famous taxidermy establishments in New York City during the mid-nineteenth century. According to one prominent ornithologist, Bell was a “friend and associate” of Audubon, Baird, Cassin, and other prominent naturalists, who named several species in his honor as a sign of their esteem.73 Like most of his fellow taxidermists, Bell not only catered to sport hunters, but also did a brisk business in mounted specimens and skins purchased by collectors and others who desired to decorate their homes and businesses.74 His shop on the northwest corner of Broadway and Worth Street became a regular haunt for hunters, collectors, and naturalists. One of those who frequented the shop as a teenager, Theodore Roosevelt, later recalled that “Mr. Bell was a very interesting man, an American before-the-war type. He was tall, straight as an Indian, with white hair and a smooth-shaven, clear-cut face; a dignified figure, always in a black frock coat. He had no scientific knowledge of birds or mammals; his interest lay merely in collecting and preparing them.”75

In addition to specimens brought in by gunners and market hunters, Bell often located prized finds at Fulton Market, one of several New York City game and produce markets.76 At a time when the line between game and nongame species remained indistinct, these markets offered an enticing assortment of birds for sale to collectors.77

New York recreational hunters and naturalists also regularly gathered at the establishment of another well-known taxidermist from this period, John Wallace, “a stout, dark-haired, . . . forceful looking man, rather short in stature with a decided cockney accent.”78 Eugene P. Bicknell, a founding member of the AOU, recalled with fondness his frequent youthful visits to Wallace’s shop on upper William Street in the 1860s and 1870s:

Thither as a youth I used often to go, hesitant of troubling this always busy man, yet impelled by expectation! Almost always there would be news of unusual local birds, for many were the specimens that came to that work-shop, and it even might befall, on good days, that I should be allowed to take into my hands some rarity not yet dispossessed of the fresh beauty of its natural form and plumage.79

For several months in 1871, fifteen-year-old C. Hart Merriam, another AOU founding member, spent his weekends away from school learning taxidermy at Wallace’s.80

One reason so many birds passed through Wallace’s hands was that his firm processed them for the millinery trade, a practice that was to become a source of tension between scientists and taxidermists with the rise of the bird protection movement a few years later.81 Working on Wallace’s eight-man assembly line provided temporary employment for the ornithologist W. E. D. Scott following graduation from the Lawrence Scientific School in 1873. Before securing a position at Princeton, Scott spent three months helping to skin, poison, and stuff the four hundred or so birds brought in daily by local gunners.82

Philadelphia was also home to several taxidermy establishments frequented by naturalists and hunters alike. Spencer Trotter’s compelling description of Chris Wood, “a typical old-time bird collector and taxidermist,” is one of the most detailed accounts of the taxidermist-naturalist that has survived and is well worth quoting at length:

“Chris” lived in a small house on the north side of Market Street west of Thirty-fourth. His taxidermic shop, on the ground floor front, I can still see perfectly, and it had a smell peculiarly its own. I can see it again whenever I get a whiff of raw bird-flesh and arsenic. Back of a counter, littered with the materials of his craft, stood “Chris,” in a cardigan jacket, skinning birds. I can see him clearly as I write this—always cheerful and friendly to the boy who must have bothered him many times. I am somewhat hazy as to a row of glass-door cases, containing mounted specimens back of where he stood, but there were drawers under the cases—deep drawers filled with bird-skins thrown in helter-skelter without labels. Mrs. “Chris,” a short darkish woman, used to urge “Chris” to “laybil” his specimens, but “Chris” knew where each one had been taken, so he said, and I believe that he was fairly accurate, though there were several hundred bird-skins in those drawers. I used to spend afternoons rummaging among these specimens and bought a good many, some very interesting ones. Twenty-five cents was the price for fairly common species of small bird, though I paid him ten dollars for the hybrid swallow which I had described. “Chris” did a fairly good business, I think, mounting birds that were brought to him by sportsmen, and he was always quite reasonable in his charges.... He was a fast and skilful worker and would strip the skin off a small bird, dose it with arsenic and push in the cotton while he talked away—one bird after another in quick succession—and the skins remarkably good, quite free from blemishes of any sort.83

More widely known was John Krider, whose shop on Second and Walnut Streets in Philadelphia “was long the popular resort of the local sporting fraternity.”84 A taxidermist, gunsmith, and professional collector, Krider traveled extensively up and down the Eastern Seaboard and as far west as Denver in search of specimens for his own collection and to sell. In the early 1870s he made several trips to Lake Mills, Iowa. There he secured specimens of a new hawk, which was later named in his honor. Unlike most taxidermists, Krider actually placed some of his field observations into print. His first book on the habits of American game birds, published in 1853, was followed by a series of notes in Forest and Stream and a second book, Forty Years Notes of a Field Ornithologist, published in 1879.85

For as long as ornithology remained focused on collecting, it remained closely affiliated with the sporting community. Even scientifically oriented ornithologists often began their interest in birds as recreational hunters, and many scientists, such as Frank Chapman, William Brewster, and Charles B. Cory, continued to enjoy hunting throughout their lives.86

COLLECTING AND IDENTIFICATION GUIDES

Naturalists constructing networks and the rise in sport hunting each contributed to the growth of bird skin and egg collecting in the United States. A third related factor, the appearance of published bird identification guides and collecting manuals, also promoted the activity of bird collecting. A steady stream of books and articles published during second half of the nineteenth century provided detailed, practical advice on how to procure, preserve, and identify birds and their eggs (fig. 6). These publications not only introduced budding naturalists to collection and identification techniques, they also served as a source of inspiration and legitimation for the activity of collecting itself. Older ornithologists from this period frequently reminisced how discovery of a particular how-to book or article had stimulated a youthful zeal in amassing specimens.

Baird, Agassiz, and other institutionally affiliated naturalists issued some of the first brief collecting manuals available in the United States.87 Their concise and widely distributed pamphlets provided rudimentary instructions on how to locate, preserve, and transport natural history specimens of all kinds. Those who sent in material, however, invariably required further guidance to refine their techniques. Information on collecting and mounting animals, particularly birds and mammals, was also available from a number of books on taxidermy aimed at recreational hunters and travelers.88 But these sources tended to be sketchy and unreliable. Not until well into the second half of the nineteenth century were more trustworthy and complete manuals readily available.

C. J. Maynard’s The Naturalists' Guide (1870) was the first American publication to provide detailed, reliable advice on collecting and preserving zoological specimens, especially birds.89 Born in Newton, Massachusetts, in 1845, Maynard left school at age sixteen.90 After attempts at farming and watchmaking, he opened a small watch repair and taxidermy shop in his hometown.91 In 1866 Maynard went into business with the taxidermist William H. Floyd of Weston, Massachusetts. One of their first jobs was to unpack and remount the large Lafresnaye collection for the Boston Society of Natural History, a task that took a full year to complete. Soon after that experience Maynard opened his own taxidermy and natural history establishment and began making sales to local collectors.92

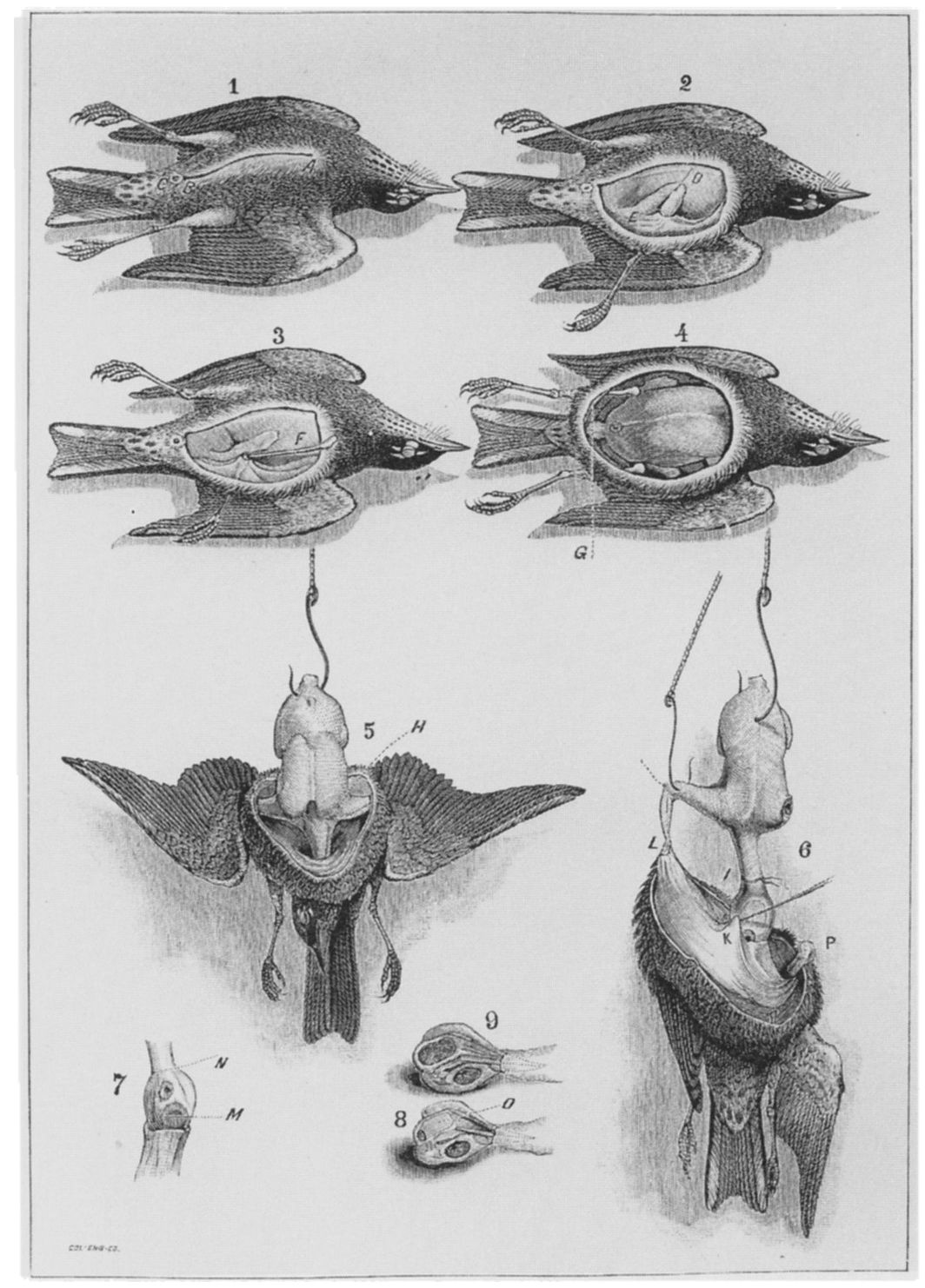

Figure 6. Illustration of how to skin a bird. From Davie, Methods in the Art of Taxidermy (1894), one of the many late-nineteenth-century manuals that introduced beginning collectors to the rudiments of securing and preserving birds and their eggs.

Besides useful advice on when and where to find birds, Maynard’s illustrated guide included recommendations on the most basic equipment—guns, shoes, clothes, and dogs—required to obtain them. Upon locating a bird, the collector needed to get it back home with minimum damage to its plumage. According to Maynard, this was achieved by using a gun of the proper bore, loaded with shot of the right size, and with just the precise amount of gunpowder to pierce and kill the bird, but not to make a second exit hole.

The most important part of Maynard’s guide was his instructions for preparing and preserving bird skins. After a brief list of the required tools and materials, he devoted several pages to the safe use of arsenic.93 Next came instructions for recording the age, sex, measurements, stomach contents, date of collection, locality of collection, and colors of the eyes, feet, and bill of the collected bird. Maynard’s up-to-date suggestions on registering specimen data were no doubt a reflection of his extensive contact with Allen at the MCZ. After detailed instructions on how to prepare bird skins, Maynard concluded the section on bird collecting with a discussion of how to mount freshly skinned and dried birds.94 Appended to Maynard’s widely read book was a catalog of nearly three hundred birds found in eastern Massachusetts.95

Elliott Coues’s Key to North American Birds (1872) was even more influential in developing American collectors.96 Ever self-assured, articulate, and controversial, Coues (pronounced “Cows”) was among the most important American ornithologists in the second half of the nineteenth century.97 Born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1842, he moved with his family to Washington, D.C., at age eleven. After obtaining his A.B. (1861) and M.D. (1863) from Columbian College, he enlisted as an assistant surgeon in the army. For the next ten years he was stationed at a variety of remote posts, including a number of western locations.

Coues first met Baird shortly after arriving in Washington as a youth. According to his biographers, for the next three decades Baird served as Coues’s “mentor, friend, and confidant, and in those years, far more than any other individual, influenced and shaped his career.”98 Baird not only helped forge the young Coues into a first-rate scientific ornithologist, he also used his extensive Washington contacts to arrange transfers to favorable collecting localities on the United States Northern Boundary Survey (1873-1876) and the United States Geological Survey (1876-1880). But because of Coues’s difficult personality, Baird never hired him on a permanent basis at the Smithsonian.

As early as 1868 Coues contemplated publishing a multiauthor “manual of American taxidermy.”99 When that project failed to come to fruition, Coues began work on “an infallible artificial Key to N.A. birds, enabling anyone, without the slightest knowledge of ornithology, to identify any specimen in a few seconds.” Coues claimed to have tested a manuscript version of the new key on his wife. Though barely able to distinguish a “tarsus from a tail,” she correctly identified all the specimens presented her.100 After providing the text, many of the woodcuts, and $1,000 for the project, Coues was greatly relieved when the Naturalists’ Agency of Salem, Massachusetts, finally published two thousand copies of the book in October 1872. According to one reviewer, soon Coues’s Key became a “familiar and useful companion alike to the amateur and professional ornithologist.”101 Coues’s reliable Key contributed more than any other single work to the tremendous growth in bird collecting that followed its publication.

The commercial and critical success of Coues’s Key encouraged him to publish again a year later. His next venture, A Check List of North American Birds (1873), was largely based on his earlier Key and, like that publication, included a number of forms designated by the trinomial nomenclature that Coues and other scientific ornithologists were beginning to promote.102 Coues hoped his new Check List, which he had printed on only one side of the paper to allow it to be used as specimen labels, would supplant a similar list issued by Baird in 1859 as the accepted standard for naming North American birds.103

Figure 7. Advertisement for Bean’s breech-loading gun cane, 1889.

A year later Coues appended the Check List to his Field Ornithology (1874), a “manual of instructions for procuring, preparing and preserving birds.”104 Written in Coues’s inimitable style, the book contained even more exhaustive instructions for the bird collector than Maynard’s earlier guide. For example, where Maynard had merely suggested the twelve-gauge shotgun as the best for birds, Coues included a lengthy discussion of other weapons as well. Like Maynard, Coues recommended the breech-loading, double-barrel shotgun as the best all-around collecting weapon, but he also discussed the pros and cons of single-barrel guns, muzzle loaders, special breech-loading pistols (“the best ‘second choice’”), and cane guns. The latter were single-barrel guns disguised to look like walking sticks (fig. 7). Although some collectors praised the unusual weapons, Coues claimed his own experience with the cane gun had been “limited and unsatisfactory”: “[T]he handle always hits me in the face, and I generally missed my bird.” Despite its shortcomings, however, there were two circumstances under which he recommended the subterfuge: “If you approve of shooting on Sunday and yet scruple to shock popular prejudice, you can slip out of town unsuspected. If you are shooting where the law forbids destruction of small birds,—a wise and good law that you may sometimes be inclined to defy,—artfully handling of the deceitful implement may prevent arrest and fine.”105

In his advice on how many and what kind of birds to seek, Coues tried to dispel widely held misconceptions about the special value of “rare” birds. Like other kinds of collectors, those amassing birds invariably went to great pains to obtain species that seemed scarce, elusive, or otherwise difficult to get. For example, in 1885, Walter Hoxie, of Frogmore, South Carolina, reported to Brewster of his repeated attempts to secure specimens of the Bachman’s warbler, which had not been collected since its original description in 1833:

This summer and fall I shot away nearly twenty five pounds of dust shot in the vain attempt to secure a specimen [of Bachman’s warbler]. I spent days and days at it. Shot every small bird that excited my least suspicion. Also a dozen or more butterflies & I even descended to lizards and grasshoppers. Everything that I couldn’t make out clearly had to suffer for I had B[achman]’s W[arbler] “on the brain.” Result—about a hundred good skins of various small birds & two hundred & sixteen “millinery’s” for which I realized 6 cents apiece. ... I shall open a spring campaign with unabated zeal & undampened hopes.106

Coues believed that with the exception of those few species truly on the verge of extinction—and Bachman’s warbler may have one of these—birds did not tend to be rare in nature. Rather, species that seemed rare in a particular geographic area were simply on the margins of their normal ranges. When collecting in a new or little-known locality, Coues recommended going after the most characteristic and abundant birds first, which he believed were the ones most likely missing from existing collections.107

In 1884 Coues published a second, revised edition of his Key, which incorporated his Field Ornithology and an extensive section on the classification and structure of birds.108 This edition, which he dedicated to Baird, contained twice as many pages and nearly four times the text as the first. Combining a collecting and identification guide in a single volume, Coues’s second edition was an even greater commercial success than the first. In his Autobiography, Frank Chapman, curator of ornithology at the American Museum of Natural History, reflected how momentous his discovery of the book in a New York City bookstore window was to his development as an ornithologist:

That was a memorable day. I acquired that book and for the first time learned that there were living students of birds, worthy successors of Wilson and Audubon. From that moment I was no longer handicapped for lack of tools. Here was a work which from the preface to index offered an inexhaustible store of information, its technicalities so humanized by the genius of its author that they were made attractive and intelligible even to the novice. In my opinion there never has been a bird manual comparable to Coues’ Key, the work of a great ornithologist and a master of the art of exposition.109

The book was so popular that Coues reported that the first printing of the second edition had been nearly exhausted only one year after it was printed.110 As a result, third (1887) and fourth (1890) editions, with only minor revisions, soon followed. A further enlarged and revised fifth edition (1903) was published several years after Coues’s death in December 1899.

In the same year as the third edition of Coues’s Key, Ridgway published a rival bird identification manual.111 In a letter to Baird requesting financial aid to complete the book in January 1886, Ridgway indicated that he had designed his manual so “the merest tyro could not fail to determine without question any species of North American bird, in any state of plumage.”112 The main difference between the Ridgway and Coues keys was that the former was based largely on the diagnostic characters of the species and genera—the particular attributes scientists used to construct their formal classifications—while Coues’s volume was avowedly artificial, arranged solely for the convenience of its users. First published in 1887, Ridgway’s Manual for the “sportsman and traveller as well at the naturalist” went into several subsequent editions.113

In 1891 two more influential collecting guides appeared. First was Ridgway’s twenty-seven-page pamphlet, “Directions for Collecting Birds,” distributed widely and without charge to Smithsonian correspondents.114 Despite its compact size, the pamphlet was a serviceable alternative for those who were unwilling or unable to purchase Coues’s more expensive Key. The same year, William T. Hornaday, former Ward’s Natural Science Establishment employee and later chief taxidermist at the Smithsonian Institution, published Taxidermy and Zoological Collecting, a lengthy book that included an extensive section on bird preparation.115 Hornaday’s advice reflected the sense of urgency many collectors brought to the pursuit of specimens as the century came to a close:

The rapid and alarming destruction of all forms of wild animal life which is now going on furiously throughout the entire world, renders it imperatively necessary for those who would build up great zoological collections to be up and doing before any more of the leading species are exterminated. It is already too late to collect wild specimens of the American bison, the California elephant seal, the West Indian seal, great auk, and Labrador duck. . . . Now is the time to collect.. . . [I]t is my firm belief that the time will come when the majority of vertebrate species now inhabiting the earth in a wild state will be either totally exterminated, or exist only under protection.116

For some individuals, like Hornaday, anxiety about extinction eventually led to a conversion from specimen collector to wildlife protector. However, most collectors seemed more intent on gathering the last examples of threatened species than on saving them.117

Most bird-collecting guides also made at least passing reference to eggs. Not until 1885, however, with the simultaneous appearance of the first editions of Oliver Davie’s Nests and Eggs of North American Birds and Frank Lattin’s Oologists’ Handbook, were inexpensive books devoted entirely to American nests and eggs widely available.118 Davie was a taxidermist and natural history dealer from Columbus, Ohio, whose identification and collecting guides enjoyed extensive sales.119 In 1889, within months after the publication of the third edition of his nest and egg handbook, he reported that twenty-four hundred of three thousand copies originally printed had already been shipped.120 Lattin’s book was a small checklist of North American birds that included exchange values assigned to most species and a set of instructions for collecting, displaying, and exchanging eggs. Lattin, a dealer from Albion, New York, offered his book as a premium for those who subscribed to his periodical, The Young Oologist (later renamed simply The Oologist).121 He also sold copies of compact checklists designed to be used by collectors to designate duplicates and desiderata for parties hoping to strike up an exchange.122

Advice on how to collect birds and eggs was also a prominent feature of the many natural history periodicals issued during the second half of the nineteenth century.123 For example, Lattin’s inaugural issue of The Young Oologist (published in 1884) included an article by the well-known egg collector, J. Parker Norris: “Instructions for Collecting Birds’ Eggs.”124 Other authors in this and similar periodicals offered recommendations on the variety of subjects suggested by their titles: “Methods of Climbing for Nests,” “Courtesy and Business in Exchanging,” “Auxiliary Gun Barrels for Collecting Bird Specimens,” “Arrangement of an Oological Collection,” “Instructions for Collecting and Preserving Birds and Eggs,” “About Collecting Chests,” and “A Convenient Collecting Gun.”125 One well-known collector recommended hiding a disassembled gun in a newspaper to escape possible prosecution whenever collecting birds out of season or in areas where other protective laws were enforced.126 Another suggested that egg collectors could obtain free use of climbing irons—tools used to scale trees—by inquiring at their local telegraph office.127

Many writers agreed that a collector received much more gratification from a “well arranged, labelled and reliable collection . . . procured entirely by the student and owner, than in a whole case . . . collected by unknown or remote persons.”128 Hard, honest work in the field resulted in not only a beautiful collection, a source of lasting pride for its owner, but also information and experience that could be gained in no other way: intimate knowledge of the habits and habitats of birds, relaxing recreation, healthy exercise, a fulfilling sense of accomplishment, and even the thrill of discovery.129 Later in life Henry Henshaw fondly recalled the excitement of his early collecting experiences while tramping with Brewster in the Fresh Pond area of Cambridge, Massachusetts: “We were constantly spurred on by the feeling that we were treading the unknown, and that at any moment we might make a new discovery.”130

Despite the widely touted benefits of personal collecting, few could resist the urge to expand their collections through purchase and exchange. In an 1888 article for the Ornithologist and Oologist, Walter Hoxie described how he gradually overcame his initial aversion to exchange as he quickly filled the gaps in his personal collection of North American birds.131 The pervasiveness of printed checklists, guides that placed an exchange value on particular species, directories of collectors, exchange notices in periodicals, and published advice on the practice is testimony to the fundamental role that specimen exchange played in the culture of collecting.132

At the same time, exchange and purchase created a new set of problems for the collector interested in ascertaining the authenticity of specimens. Fraud was an ever-present possibility, and deception might take many forms. Extralimitals, birds found outside their usual range, were especially prized by collectors, and to raise the value of relatively common species, dealers and exchangers sometimes lied about the true geographic origin of a particular specimen.133 Another common ploy was to falsely identify specimens and pawn them off on unsuspecting collectors.134 It was difficult for all but the most knowledgeable ornithologist to recognize indistinct species and all the variations in plumage due to age, season, sex, and location. The practice of intentionally misidentifying specimens to increase their value became easier when scientists began to delineate subspecies, which were typically based on minute distinctions not discernible to the casual collector.135

For egg collectors, fraud was especially problematic and difficult to detect. Unlike skins, which carried their own identification with them, eggs could not be definitively identified without reference to the parent birds. Egg collecting manuals invariably recommended taking the parents whenever there was the slightest doubt about their identity, advice that was frequently ignored.136 As a result, collectors receiving eggs were almost entirely at the mercy of the honesty and knowledge of the other party. Beyond lying about the identity or geographic origin of birds, which were problems even for skins, some unscrupulous individuals even tried painting their eggs to resemble rarer species.137 Notices warning collectors of these and other fraudulent practices regularly appeared in natural history periodicals.138

In the last three decades of the nineteenth century, the wide availability of bird-collecting manuals, identification guides, and how-to articles in periodicals opened the world of ornithology to a growing number of collectors. By providing readily available information on procuring, preserving, and identifying birds, these publications helped decentralize the collecting networks that had previously been focused on the small number of expert naturalists. One result of this increasing independence was that collectors became more willing to challenge the authority of expert naturalists on whom they had once depended for even the most basic information on their favorite avocation. At the same time, the large natural history periodical press provided a public forum for airing the aspirations and concerns of collectors. The broader community of collectors soon came to criticize scientists on a variety of issues.

PERILOUS PURSUITS

Bird and egg collecting were not just strenuous activities; they presented real dangers to their practitioners. Injuries were common, and occasionally even deaths occurred. Many of these hazards were not specific to the activity of collecting. Bruises, broken bones, and insect bites were the occasional consequence of any form of outdoor activity. But the experience of wandering around the countryside with loaded weapons and climbing cliffs and trees exposed bird and egg collectors to unique perils.

Some of these dangers resulted from the unusual circumstances in which collectors sometimes found themselves. Throughout most of the middle decades of the nineteenth century, when the federal government was engaged in a brutal campaign to conquer Native Americans, frontier collectors often felt threatened just being alone in the wilderness. One particularly productive collector from this era, Charles E. Bendire, amassed an immense number of eggs while stationed at western outposts in the 1850s through the 1870s.139 More than once Bendire found himself in tight situations out in the field. His closest call probably came in Arizona in the early 1870s.140 After climbing a cottonwood tree in pursuit of zone-tailed hawk eggs, Bendire noticed several Apache Indians lingering on the horizon. Shaken at the possibility of being spotted in such a visible and vulnerable position, Bendire nonetheless maintained his composure. He carefully placed the prized egg in his mouth, shimmied down the tree, and quickly rode back to the fort. After prying apart his jaws to remove the large egg from his mouth, Bendire summoned the troops, who took off in pursuit of the Apaches.

Firearms presented dangers no matter where the collector ventured, and collecting guides invariably contained warnings about the need for extreme caution when carrying loaded guns.141 Yet despite these warnings, injury from accidental discharge did occasionally occur. In 1895 John S. Cairns, a young collector from Weaverville, North Carolina, was killed when his gun went off unexpectedly while collecting in the Black Mountain area of the state.142 More celebrated was the accidental death of Joseph H. Batty, a taxidermist and millinery dealer turned professional collector for the American Museum of Natural History.143 During his three and one-half years in Latin America collecting for the AMNH, Batty had experienced a great deal of hardship, including drought, plague, and political revolution.144 Despite these and other obstacles, however, he managed to send back over three thousand mammals and twice that many birds before his gun accidently fired, killing him instantly in 1906. In a revealing obituary Allen portrayed Batty as a martyr to science and endowed him with the attributes of the ideal collector: “a man of great physical endurance, courage, persistency, and enthusiasm.”145

As a group, egg collectors seemed to fare worse than their skin-collecting colleagues. Nests built in the heights of trees and cliffs to thwart potential predators were also strong deterrents to all but the most hardy collectors. For example, in 1921 Richard C. Harlow, a prominent oologist and coach of the Penn State boxing team, narrowly escaped death while trying to collect highly desirable raven eggs in the Seven Mountains region of Pennsylvania.146 Midway down a ninety-foot cliff, a rock dislodged and struck Harlow in the head. The blow stunned him, forcing him to loosen his grip on the rope. Somehow he managed to retain a partial hold while sliding rapidly down to the ground. After lying unconscious for a half hour, he stumbled to the nearest town with relatively minor injuries: one hand cut to the bone, the other badly seared, and a severely bruised head.

Other egg collectors were less fortunate. In 1913 thirty-three-year-old William B. Crispin of Salem, New Jersey, fell more than two hundred feet to his death while trying to collect the contents of a duck hawk’s nest from the Nockaminon Cliffs, a few miles up the Delaware River from Philadelphia.147 He was not discovered until a day after the accident, when several young women collecting wildflowers stumbled across his body.

Francis J. Birtwell, a former student of the Bussey Institute and the Lawrence Scientific Schools at Harvard, was forced to leave for the drier environs of New Mexico after being diagnosed with tuberculosis.148 Enrolling in the Territorial University, Birtwell began a study of New Mexico birds for his graduation thesis. One day in 1901, while collecting eggs from near the top of a sixty-five-foot pine in Willis, New Mexico, Birtwell panicked when gusting winds suddenly began to sway the tree. He called to his recent bride for help, and she quickly secured a rope and several young men to aid the shaken collector. But while he was being lowered by a rope thrown from below, a knot somehow became lodged in a fork of the tree, leaving Birtwell dangling thirty feet from the ground. In the process of trying to free himself, the rope slipped from under one of his arms and fastened firmly about his throat. Despite repeated attempts to save him, Birtwell soon ceased his desperate struggles. It was not until an hour later that his body was finally lowered to the ground.

The tragic death of John C. Cahoon, a well-known collector and dealer from Taunton, Massachusetts, elicited an unprecedented outpouring from the collecting community. At an early age “he became interested in birds and animals, guns, pistols, hunting and fishing.”149 In 1878 the fifteen-year-old Cahoon began collecting and mounting birds while serving as an apprentice in a local pharmacy. Over the next few years he devoted increasing time to his favorite pursuit, and by the early 1880s he had opened a small natural history business. For six months in 1887 he collected in Southern Arizona and Mexico for William Brewster.

After collecting in St. John’s, Newfoundland, in 1889, Cahoon became the subject of a newspaper article that began with the headline “Daring Act of American Ornithologist at Birds Island. He Scales a Perpendicular Cliff Three Hundred Feet High. Shuddering Fishermen Lean on Their Oars and Witness the Dangerous Ascent.” The article went on to describe Cahoon’s exploits, stressing the calm demeanor of the brave young collector even when his life was clearly endangered: “With death staring him in the face, he was quite cool and collected, talking with the men below. He is a man of splendid nerve power.”150

When collecting from nearby cliffs two years later, Cahoon was not so calm and composed. After lowering himself from the top of a two-hundred-foot cliff and gathering four eggs from the nest of a raven, Cahoon was in the process of making his ascent when he reached a point where the cliff was overhanging. With the weight of his body holding the rope tightly against the rocks, Cahoon struggled for twenty minutes in an attempt to continue upward. Exhausted, he then tried to lower himself to the shelf where the raven’s nest rested. But with his strength sapped, Cahoon’s descent became increasingly uncontrolled. Not until the following day were authorities able to retrieve his body from the blood-soaked waters at the base of the cliff. In the notice of his tragic death, the editor of the Ornithologist and Oologist lionized Cahoon as “A good boatman, a determined collector, a dead shot, of a kind and joyous disposition, honest brave and accommodating,—a typical American collector."151

WOMEN ORNITHOLOGISTS

One of the most striking features of the ornithological community in the second half of the nineteenth century is that it was almost entirely male. During this period, women occasionally became accepted, if marginal, members of the botanical and entomological collecting networks in the United States.152 However, only one woman, Martha Maxwell of Colorado, is known to have done any bird collecting on her own during the entire nineteenth century.153

Tramping through the countryside in search of specimens ran against the grain of the prevailing ideology that bound middle-class women tightly to the domestic sphere.154 As Nell Harrison, a female schoolteacher from York, Nebraska, complained in 1902, “Men can go freely into the fields and follow the birds everywhere, while fashion and conventionality debar women from the same privilege.”155 But bird and egg collecting also posed their own, more unique difficulties for women. First, ornithological collecting demanded proficiency with a gun, a skill that few women cultivated.156 Second, collectors were required to take the lives of creatures that were often portrayed in anthropomorphic terms. Birds sang, performed courtship rituals, cared for their young, and exhibited other behaviors that were easy to characterize in humanlike terms. In particular, the nurturing qualities often associated with birds seems to have elicited special sympathy from women, who were expected to serve a similar role in the home. And finally, climbing trees and scaling cliffs were physically demanding and dangerous activities even for male collectors.

Beyond Maxwell, there were a few other women who made a limited entry into the nineteenth-century ornithological community predominantly focused on collecting. Graceanna Lewis was John Cassin’s “one and only student” at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia from 1862 until his death in 1869.157 Both were Quakers with egalitarian leanings: Lewis once remarked of Cassin, “[H]e never seemed to think it strange that a woman should wish to study.”158 Although never known to have collected, with Cassin’s careful guidance and access to the unrivaled academy collection, Lewis became an accomplished and widely recognized systematist: she discovered a new species among the birds at the academy, published several articles, offered public lectures on ornithology, and had her papers presented before scientific societies. In addition, she issued the first installment of a projected ten-part Natural History of Birds in 1868. Whether due to the failure to obtain the necessary subscribers or the death of her supportive mentor and close friend Cassin in 1869, Lewis failed to complete the work.

The women responsible for the publication of Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio had better luck bringing their ambitious project to fruition. In July 1879 Genevieve Estelle Jones and Eliza J. Schultze issued their first three hand-colored, life-size plates to immediate critical acclaim (fig. 8). In his reviews of this and subsequent installments, Elliott Coues frequently compared the exquisitely executed lithographs to the work of Audubon.159 But after completing a few additional plates, the thirty-two-year-old Genevieve succumbed to typhoid fever.160 Eliza Schultze continued to draw the plates, while Genevieve’s mother, Virginia (Smith) Jones, stepped in to color them. In 1880 Schultze withdrew from the project entirely. Virginia Jones completed the remaining plates, and two local women were hired to do most of the coloring. All of those involved with the project were proud that the drawings were based on freshly collected material, but it was Genevieve’s brother, the physician Howard Jones, not the women, who gathered the specimens upon which the illustrations were based. He also wrote the text for the book.161

Figure 8. Plate of the field sparrow’s nest and eggs, from Jones and Jones, Illustrations of the Nest and Eggs of the Birds of Ohio (1886). Although highly praised at the time of publication, the work soon fell into obscurity.

When women were involved with bird collecting, it was usually behind the scenes, as (often unacknowledged) helpmates for their husband collectors. For example, in the spring of 1898, Frank Chapman spent his honeymoon in familiar collecting grounds in the Indian River region of Florida. Following a successful search for the then-rare (and now extinct) dusky seaside sparrow, Chapman’s recent bride, Fannie Bates Embury, decided to try her hand at bird-skinning. Much to Chapman’s “astonishment, joy, and chagrin,” she almost immediately mastered the art.162 Fannie Chapman then suggested that her husband mount an expedition to a nearby island containing a breeding colony of pelicans. Aware of the special difficulty of preparing the oily skinned, oddly shaped birds, Chapman reluctantly agreed. Fannie Chapman handled the difficult task admirably, and the specimens eventually became part of a large habitat group at the American Museum of Natural History. From that point on, she regularly served as Chapman’s assistant on expeditions.

Except for the case of women, the ornithological community remained relatively open throughout much of the second half of the nineteenth century. A shared interest in specimens united the scientists, sport hunters, collectors, dealers, and others who comprised that extended and diverse community. As the nineteenth century came to a close, however, many factors converged to divide that community. The next several chapters show how a series of institutional, intellectual and social transformations created a wedge between the more technically oriented ornithologists and other bird enthusiasts.