CHAPTER SEVEN

Birdwatchers, Scientists, and the Politics of Vision

COOPERATION AND CONFLICT

In 1916 the British zoologist Julian Huxley, then a young assistant professor of biology at the Rice Institute in Texas, lamented the increasing polarization between "amateur” field naturalists and “professional” biologists.1 Huxley’s “Bird-Watching and Biological Science,” a lengthy two-part article published in the Auk, argued that the recent growth of popular interest in observing wild birds offered a unique opportunity to begin bridging this gap. With continued encouragement and proper guidance, the “vast army of bird-lovers and bird-watchers” could begin providing the data scientists needed to address what Huxley called the “fundamental problems of biology.”2

To a large extent Huxley was preaching to the converted. Following the lead of their British counterparts, during the previous three decades American scientific ornithologists had repeatedly urged people to venture out to view their native birds. Although the specific term Huxley used—“bird-watching”—had yet to catch on in the United States, the activity it sought to describe clearly had.3 By the end of the nineteenth century, thousands of middle- and upper-class birding enthusiasts were rushing to purchase field guides, erect bird feeders, and join Audubon societies.4 For years bird collectors had provided the study skins necessary to construct a definitive inventory of North American bird forms, the central defining mission of scientific ornithology in the United States since the middle of the nineteenth century. Now some American ornithologists began arguing that networks of birdwatchers might provide the raw data on distribution, migration, and life-history to help forge a “new ornithology.”

However, scientific ornithologists were far from uniformly enthusiastic about the growth of popular interest in birdwatching. Cooperative observational networks in which scientists dictated the terms of membership, monitored the contributions, and analyzed the results were one thing. But the proliferation of bird-watchers’ “sight records”—published observations of species and subspecies beyond their established ranges—was something else entirely. Whether reliable or not, these records became a permanent part of the literature and the building blocks for the faunistic catalogs and taxonomic monographs that had long represented the core of ornithological research in the United States.

Nowhere is concern about the growth of sight records more evident than a letter to the editor that Jonathan Dwight published in the Auk in 1918, just two years after Huxley’s article.5 In many ways the letter’s author was much more typical than Huxley of scientific ornithologists in the United States at the time.6 Like most of his American colleagues, Dwight lacked either formal training or a paid position in ornithology, but he was active in the AOU, he published regular contributions to the scientific literature, and he eventually gathered the largest private collection of North American birds ever amassed.7

Dwight presented an anecdote to demonstrate the grounds for concern that he and many of his scientifically oriented colleagues shared about the recent increase in sight records. The incident involved a report he had received from two unnamed birdwatchers in Connecticut who claimed to have seen two male scarlet tanagers early in December of the previous year. If accurate, the record was potentially important because the scarlet tanager was a migratory species that had yet to be found so far north at such a late date. As Dwight pointed out, however, the record was clearly in error. Although his correspondents claimed to have been experienced and conscientious field students, they were apparently ignorant of a fact known to every serious ornithologist worthy of the name: in the autumn the male scarlet tanager sheds its characteristic red coat for one that is a less-descript dull yellow-green. The overzealous observers had apparently mistaken the ubiquitous cardinal for the more elusive scarlet tanager and then compounded their indiscretion by passing on their observation to Dwight. In this case the error was so obvious it was unlikely ever to have found its way into print. The incident was troubling nonetheless because it was symptomatic of the kind of mistakes that did appear in the literature with disturbing frequency as popular interest in birds had grown. As Dwight argued at the close of his letter, “truly a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.”8

Huxley’s invitation to cooperation and Dwight’s rebuke represent extremes in the spectrum of responses to the emergence of birdwatching as an important middle-class leisure activity in the United States. Keenly aware of the central role that bird collectors had once played in the development of their field, many American ornithologists embraced Huxley’s view that birdwatching enthusiasts represented potential allies in the production of knowledge. Scientists anxious to recruit members for observational networks and supporters for their conservation initiatives were among the most vigorous promoters of birdwatching. Yet these same scientists clearly experienced discomfort when birdwatchers began to independently publish their sight records in the dozens of turn-of-the-century ornithological periodicals. In the eyes of scientific ornithologists, the appearance of dubious, unverifiable records represented a threat to the authority of the scientific discipline they had struggled long and hard to construct.

A FIELD GUIDE TO BIRDWATCHING

The rise of public interest in birdwatching and the growth of the Audubon movement were so intimately related it is difficult to disentangle the lines of cause and effect between the two. What is clear is that both began in the last two decades of the nineteenth century and both were expressions of a larger Romantic backlash against an increasingly urbanized, industrialized society that threatened to irrevocably alter the American landscape.

From the beginning Audubon leaders recognized the crucial role birdwatching might play in furthering their protectionist agenda. By reinforcing an emotional and aesthetic bond between humans and birds, birdwatching helped convert ordinary citizens into ardent conservationists. Whether they ventured out into the field or simply gazed at the birds attracted to their newly installed feeders, birdwatchers found profound delight in the animated, vocal, and often brightly colored species they rushed to observe.9 By the turn of the century Audubon societies across the nation were promoting the activity through a variety of means, ranging from organizing regular field trips, hawking field guides, and issuing checklists of local species to promoting bird study in schools, sponsoring lecturers, and offering advice on how to build feeders, mix food, and locate bird baths.10

The appearance of a new kind of bird identification guide reflected as well as promoted popular interest in birdwatching. Like those who engaged in other forms of scientific and popular natural history, birdwatchers felt the urge not merely to observe wild nature; they also wanted to pin names on the species they located. The problem was that the standard identification manuals bird collectors had long found indispensable, like Elliott Coues’s Key to North American Birds (1872) and Robert Ridgway’s Manual of North American Birds (1887), were large, cumbersome volumes that were difficult to carry in the field and designed to be used only with the dead specimen in hand.11 In the late 1880s and early 1890s, however, American authors began publishing the first compact identification guides designed for field use to help birdwatchers discover the names of the living birds they encountered in the wild. Initially these field guides relied on lengthy species descriptions and analytical keys, similar to those found in the older collecting manuals. When it became clear that keys confused and intimidated many novice birdwatchers, authors increasingly turned to illustrations, especially color illustrations, to simplify field identification.

The first of this new generation of field guides came from the pen of Florence Merriam.12 From an early age Merriam developed a keen interest in natural history while tagging along on excursions with her older brother, the ornithologist and mammalogist C. Hart Merriam. In 1886, while a student at Smith College, she organized an early local Audubon chapter to discourage the practice of wearing feathers.13 Using the experience gained in trying to teach her classmates the names of the birds they encountered on their field trips, in 1887 Merriam began publishing a series entitled “Hints to Audubon Workers: Fifty Birds and How to Know Them” in Grinnell’s Audubon Magazine.14 The lengthy series, which included brief descriptions of the most common species found in the eastern United States, continued until 1888. At the conclusion of the last installment, Merriam appended a field key—arranged by habitat preference, color, song type, behavior, bill shape, and nesting site—as an aid to identification. It was the first time anyone had published a system of field identification for birds. In 1889 she expanded the text of her lengthy series into her first book, Birds through an Opera Glass, which included a total of seventy species.15 Although sparsely illustrated by the standards of subsequent field guides, Merriam’s book inspired thousands to take up the practice of birdwatching.

Merriam’s best-selling guide also signaled the beginning of an avalanche of similar publications. Merriam herself subsequently issued numerous nature essays and field guides, including A-Birding on a Bronco (1896), Birds in Village and Field (1898), and Handbook of Birds of the Western United States (1902). Several other female authors—including Mabel Osgood Wright and Neltje Blanchan—also published best-selling identification guides before the turn of the century.16 Although scientific ornithology had long been an overwhelming male-dominated enterprise, many of the authors of field guides, devotees of birdwatching, and supporters of the Audubon movement were female. While I have discovered little direct evidence that this fact alone contributed to the decidedly negative response that some (male) scientific ornithologists had to the rise of birdwatching, no doubt it did play a role.

By far the most influential figure in churning out new field guides and otherwise promoting the new birdwatching craze was Frank Michler Chapman, who joined the Department of Ornithology at American Museum of Natural History in 1888 and remained at the institution for over a half century.17 Although he occupied one of the few professional positions in ornithology available in the United States at the time, Chapman was equally at home in the worlds of scientific ornithology, wildlife conservation, and birdwatching. He brought these sometimes conflicting interests together when he began issuing the periodical Bird-Lore in 1899, a little over a decade after Grinnell discontinued Audubon Magazine. The new periodical was a “popular journal of ornithology . . . addressed to observers rather than to collectors of birds,” an orientation reflected in its motto—“A Bird in the Bush Is Worth Two in the Hand.”18 Not only was Bird-Lore brimming with useful information for bird enthusiasts of all ages, levels, and degrees of interest, it also served as the official organ of the various state Audubon societies and later the National Association of Audubon Societies.

Chapman’s interest in bridging the gap between technical and popular ornithology had already manifested several years before the inaugural issue of Bird-Lore. His first major publication, Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America, originally issued in 1895 and reprinted in several editions, contained detailed advice on locating, collecting, and preserving birds “along approved scientific lines” together with a series of analytical identification keys designed to be used with specimens in the hand.19 Almost as an afterthought, Chapman appended a series of helpful hints on naming the birds “without a gun” as well as an eight-page artificial field key—based on plumage colors and body size—to aid in identifying the more common eastern forms. Following a lengthy introduction to the study of birds, the bulk of the book consisted of somewhat technical descriptions of each of the more than five hundred species found in eastern North America.

Although Chapman’s Handbook inspired a generation of scientifically oriented ornithologists, its general collecting orientation, tedious species descriptions, comprehensive scope, and relative lack of illustrations proved too daunting for many beginning birdwatchers. Inspired by the success of Merriam’s and Wright’s popular guides and hoping to reach a larger audience, soon Chapman tried his hand at a second book, Bird-Life (1897).20 Like most identification guides on the market at the time, Chapman’s latest venture limited its coverage (in this case to just upwards of a hundred of the most common species), offered brief, chatty descriptions, and included copious illustrations (in this case based on carefully rendered black-and-white drawings by the artist-naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton).21 Chapman’s book also included a modified version of the field key found in his Handbook to aid in identifying birds by sight alone. The scope and general tone of the book suggested that it was intended for the rank beginner.

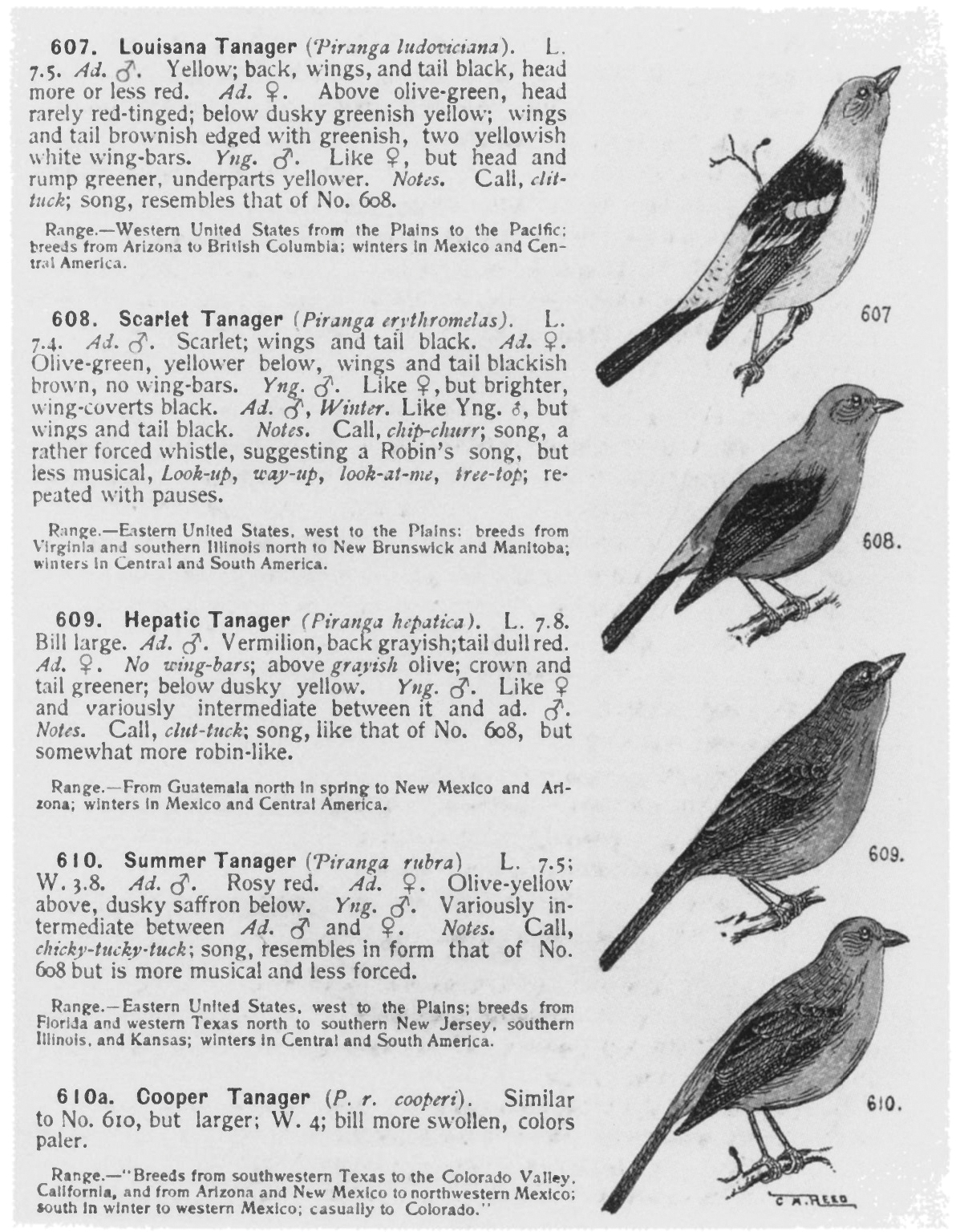

Chapman’s next field guide, Color Key to North American Birds (1903), represented a more decided break from tradition. According to the book’s introduction, the author hoped to “make bird study possible for the thousands” who were intimidated by the idea of using analytical field keys.22 The new volume was both easier to use and much more comprehensive than other turn-of-the-century bird guides. Each of the more than seven hundred species was illustrated with a crude but serviceable line drawing colored with “those markings which most quickly catch the eye.”23 Although Chapman continued the standard practice of organizing the birds into scientific Orders, an arrangement he considered both “natural” and “easily comprehended,” within each Order he grouped birds according to their predominant colors or markings. To facilitate comparison of birds that were most similar in overall appearance (and to make the volume more economical to publish), Chapman placed the drawings and descriptions of several similarly colored species on a single page (fig. 25).

The illustrator for Chapman’s Color Key was Chester A. Reed, the twenty-six-year-old son of the taxidermist, natural history dealer, and publisher Charles K. Reed of Worster, Massachusetts.24 The Reeds had catered to the natural history specimen trade since the late 1880s, but with the emergence of the Audubon movement and the resulting legal restrictions on collecting, they reoriented their business toward birdwatching. In 1901 they began publishing American Ornithology, a copiously illustrated monthly designed to “present to the public a complete popular account of every bird found in North America.”25 Following the collaboration with Chapman, in 1906 the younger Reed issued a two-volume guide to birds east of the Rocky Mountains that became a standard for beginning birdwatchers until the 1930s.26 The first volume included water birds, game birds, and birds of prey, while the second covered land birds. A third volume, posthumously published in 1913, treated birds west of the Rockies.27

Straightforward in design and use, Reed’s guides contained a primitively rendered color portrait of each species along with a terse, no-nonsense description of its major characters, haunts, songs, nest, eggs, and range. The guides were compact—measuring approximately 3" x 5"—and contained only a single species on each page. By flipping through the illustrations, even children were supposed to be able to discover the name of most birds they were likely to encounter in the wild. Reed’s immensely popular guides remained in print until the 1950s.28

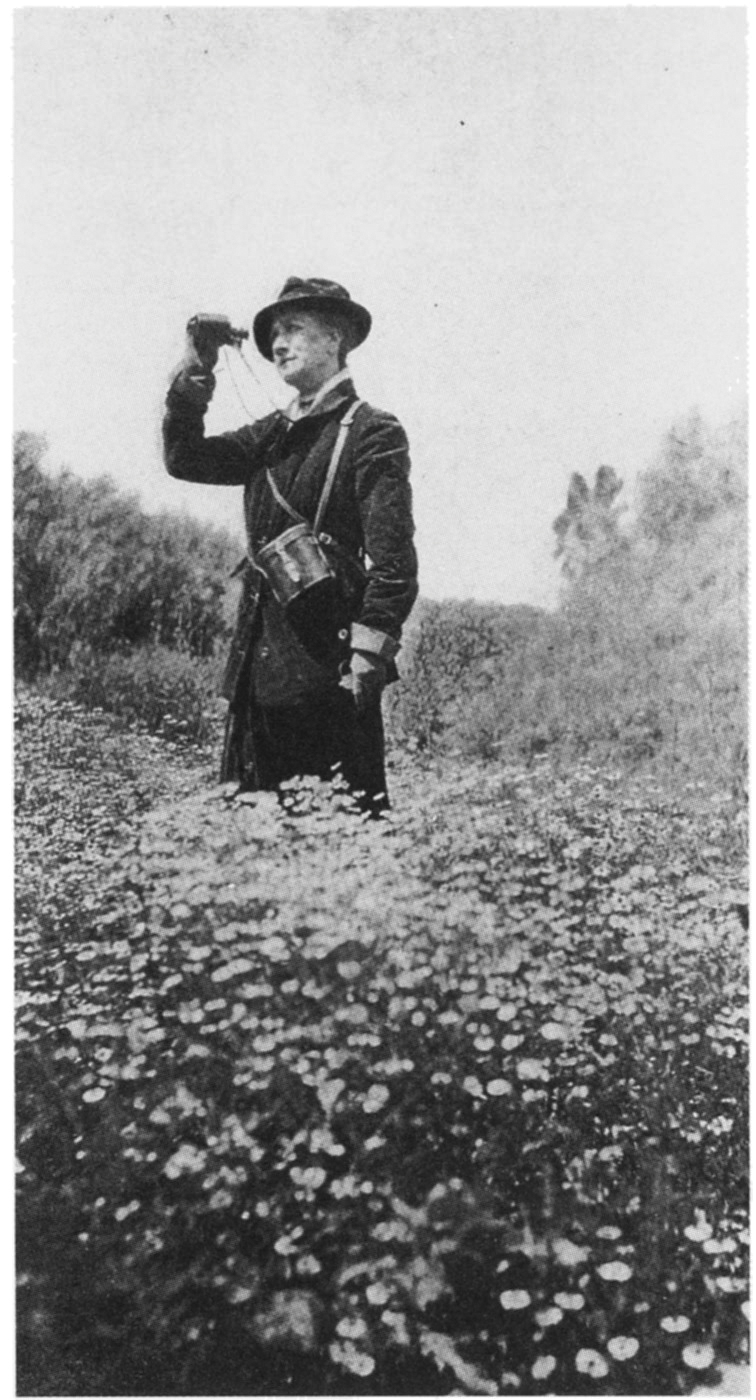

Along with refinements in field guides, developments in optical technology also contributed to the growth in popularity of birdwatching. In 1853, when Henry David Thoreau decided he wanted a closer look at the birds near his home in Concord, Massachusetts, he trekked into Boston to buy himself a spyglass, a simple Galilean telescope consisting of a concave eyepiece and a convex objective lens that had long been used for military and navigational purposes.29 Three decades later, when thousands of Americans began to follow Thoreau’s lead, opera and field glasses (fig. 26) were clearly the viewing instruments of choice. Consisting of two Galilean telescopes connected together, most often with a common focusing mechanism, binoculars had first been placed on the market in Europe in the early nineteenth century, though they apparently were not widely available in the United States until after the Civil War.30 Field and opera glasses provided only limited magnification (ca. 3x or 4x), but they were compact and had a relatively wide field of view, making them ideal for locating quickly moving objects like birds.

Figure 25. Illustration of tanagers from Chapman’s Color Key to North America Birds (1903). Chapman’s book provided one of the models for Roger Tory Peterson’s now legendary field guide, which was first published in 1934.

Figure 26. Field glasses and binoculars, ca. 1920s. By the turn of the century, birdwatchers had a variety of viewing instruments from which to choose. Left to right: opera glasses, field glasses, a spyglass, prism binoculars, and the Biascope, a particular brand of field glasses.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, several European instrument makers began experimenting with prisms to increase the focal length of binoculars without unduly increasing their size or weight. But it was not until 1893, when the famed German physicist and optical engineer Ernst Abbe began manufacturing the first quality prism binoculars at the Zeiss Works in Jena, that the invention was acceptable and widely available.31 Prism binoculars provided greater magnification (ca. 7x to 10x) and a larger field of view than field glasses, but they were also quite expensive. Nonetheless, they provided unequaled viewing opportunities for those with deep enough pockets, and they quickly became standard equipment for serious birdwatchers.32

Photography also played an important role in promoting the growth of birdwatching. The fast lenses and dry plates necessary to capture images of wild animals in their natural habitats first began to be developed in the late 1870s, but it was not until two decades later that negative emulsions were sensitive and reliable enough and camera lenses fast enough to achieve good results consistently.33 Once these technological limitations had been broached, nature enthusiasts began producing a steady stream of wildlife photographs. By the 1890s photographs of birds began appearing regularly in scientific and popular periodicals as well on lantern slides that frequently accompanied popular lectures on birds, though often these early images were of captive animals or stuffed specimens placed in their natural habitat. In 1900 Frank Chapman published the first American book on the subject, Bird Studies with a Camera, which was quickly followed by a series of similar titles by Francis H. Herrick, A. Radclyffe Dugmore, William Finley, and Herbert K. Job.34 Bird photography promoted birdwatching by providing the public with inspiring images of the bird in nature and the birdwatching photographer with a tangible reminder of his or her encounters in the wild.35

And finally, developments in transportation technologies carried an increasing number of birdwatching enthusiasts to the nation’s fields and forest. The so-called safety bicycle, first placed on the market in the 1880s, was quiet and relatively easy to operate. It also allowed its riders to cover more territory in a given period than walking, while providing more flexibility than the railroad or the horse.36 The strong endorsement of one bird student in 1890 is typical of the passion with which many naturalists extolled the virtues of the bicycle:

I think the most healthful, instructive and pleasing exercise one may take, is to roam the country, through forest and meadow, and over brook and stream, in pursuit of the study of birds; and I think the second most healthful and pleasing exercise is bicycling; aside from walking, there is no exercise that puts every part of the body so in motion as does bicycling . . . and now combining these two pleasures, we have the sum total of health and happiness.37

After the turn of the century, birdwatchers increasingly turned to yet another new invention—the automobile—to transport them to their favorite haunts. Cars carried birders greater distances, allowed more total time in the field, and provided the opportunity to cover a greater diversity of habitats than other previous modes of transportation. What began as an expensive plaything for the rich became increasingly affordable by the 1910s and 1920s. And as the price plummeted, Americans rushed to adopt the new technology that was to change profoundly so many aspects of their lives.38

Easy-to-use field guides, more powerful binoculars, new photographic methods, and developments in transportation technologies clearly enhanced the experience of most birdwatchers, but alone they fail to explain the phenomenal turn-of-the-century popularity of the “rare and absorbing ritual” of birdwatching.39 Rather, the explanation ultimately turns on the transformation of values that occurred during this period. By the end of the nineteenth century, some Americans were beginning to relinquish the pervasive view that birds and other forms of wildlife were merely objects; increasingly they came to be appreciated as individuals that were in some ways analogous to humans.40 Or as Frank Chapman once commented in another context, birds “have not only a beauty which appeals to the eye, but often a voice whose message stirs emotions to be reached only through the ear.. . . [T]hey further possess humanlike attributes which go deeper still, arousing in us feelings which are akin to those we entertain toward our fellow-beings.”41

While we lack direct measurements of precisely how many Americans answered the call of the wild bird at the turn of the century, there are indirect means suggesting the number was quite significant. One such indicator comes the world of advertising. Beginning in the 1880s, Church and Co., the manufacturer of Arm and Hammer and Dwight Baking Sodas, began including small, chromolithographed bird cards with their product in an effort to encourage brand loyalty.42 The cards, which continued to be issued in numerous series over the next six decades, were designed to be collected, traded, and pasted into albums. They proved so effective in boosting sales that several other manufacturers copied the practice (fig. 27). By 1912 Chapman proclaimed that the appearance of the latest series of bird cards (this time from an American chewing gum maker) heralded the dawn of an “ornithological millennium.”43

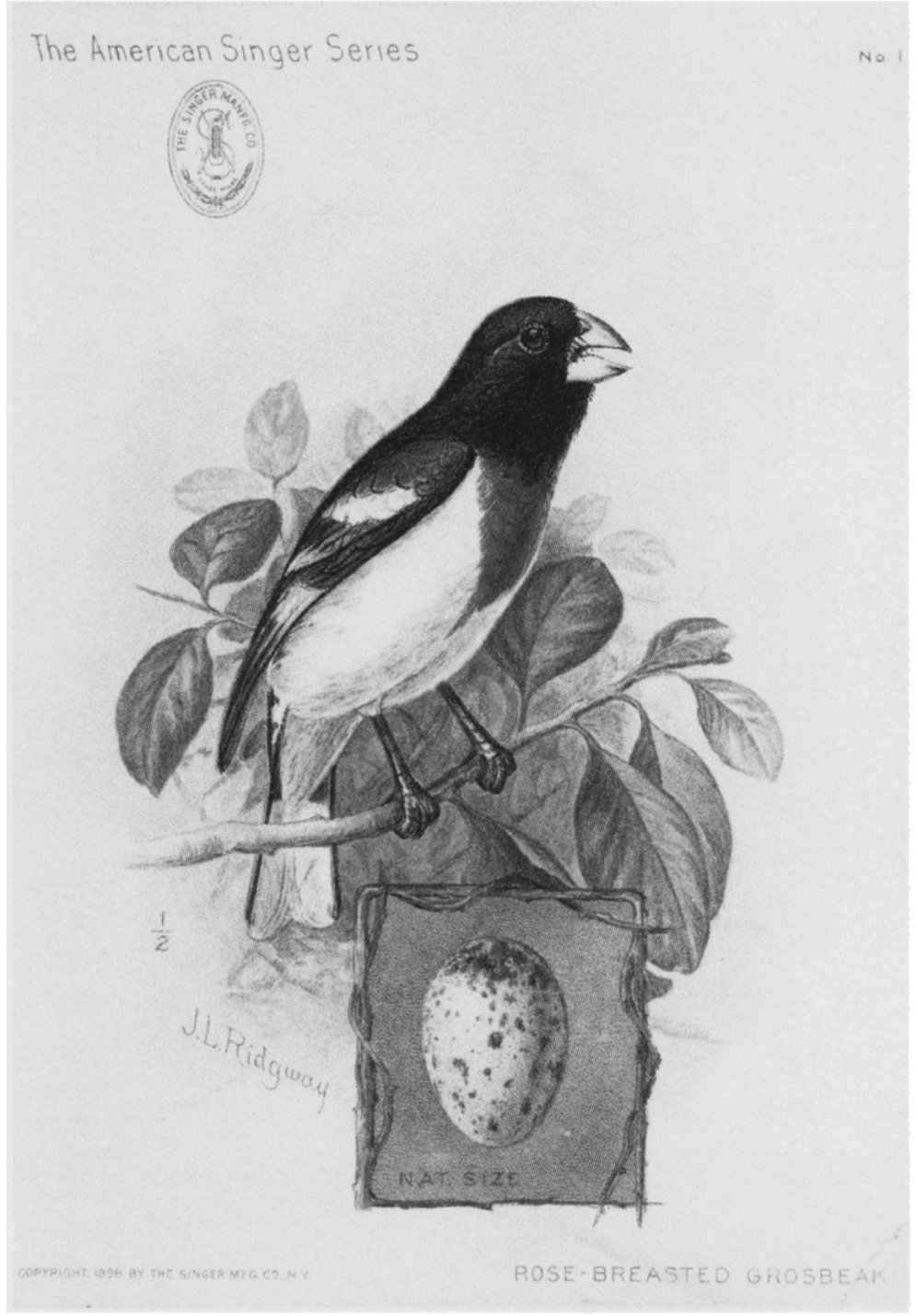

Figure 27. Trade card depicting a red-breasted grosbeak, 1898. The first of the sixteen-card “American Singer Series” issued by the Singer Manufacturing Co. The drawings for this series were by John L. Ridgway, brother of Robert Ridgway, who also illustrated scientific publications.

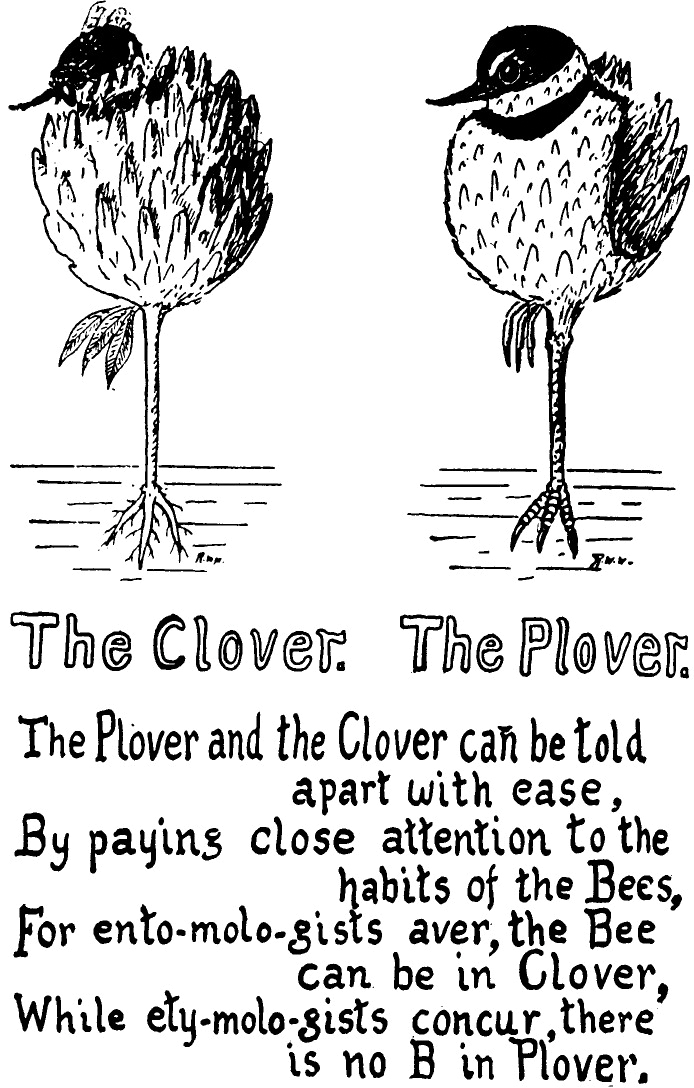

Figure 28. Woodcut from the physicist Robert Wood’s delightful satire of held guides, How to Tell the Birds from the Flowers (1907).

Within the first several decades of the twentieth century, birdwatching had become so ingrained in American culture that it even became the object of humor. In 1907 the noted American physicist Robert Williams Wood published a satirical field guide entitled How to Tell the Birds from the Flowers (fig. 28).44 The whimsical book, which had originally been composed to amuse his children, featured woodcuts juxtaposing pairs of common birds and plants together with descriptions written in an ingenious nonsense verse. Wood’s delightful volume was so well received that it went through several editions and dozens of printings over the next forty years.45 Another good-natured gibe at birdwatching appeared in 1935, when the New Former published a Gluyas Williams cartoon (fig. 29) depicting a group of “Audubon Bird Walkers” adding a scarlet tanager to their list.46

Williams’s cartoon suggests a further indication of the growing popular interest in birdwatching: the proliferation of bird clubs.47 As Chapman noted in 1915, these institutions were different from the more traditional ornithological clubs and societies that had been around in the United States since the 1870s. Where earlier ornithological organizations were composed mainly of “bird-students” who hoped to pursue “original scientific research,” the members of new bird clubs were primarily “bird-lovers” interested in “the development of methods which will tend to increase our intimacy with the birds.” Although a desire to pursue scientific research might eventually develop in some members, bird clubs generally avoided technical discussions of “nomenclature, classification and avian psychology” to pursue an interest in “nesting-boxes, bird-baths and feeding stands.”48 The first bird clubs began to be organized just after the turn of the century, and within three decades there were hundreds in communities across the United States.49 In membership and function, bird clubs were often indistinguishable from local Audubon societies.50

Figure 29. Cartoon depicting birdwatchers. By the 1930s hundreds of local bird clubs and Audubon societies across the United States and Canada promoted the activity of birdwatching. Drawing by Gluyas Williams; © 1935, The New Yorker Magazine.

Perhaps the most useful indicator of the scope of birdwatching at the turn of the century is the sale of field guides. When Frank Chapman launched Bird-Lore in 1899, he reported that during the previous six years New York and Boston publishers had sold more than seventy thousand popular books on birds.51 By 1933, one year before the publication of the first edition of Roger Tory Peterson’s now legendary field guide, Neltje Blanchan alone had sold more than 150,000 copies of Bird Neighbors, while Frank Chapman had sold more than 230,000 copies of his popular bird books, and Chester Reed, a phenomenal 633,523 copies of his compact bird guides.52 And these three authors were just the tip of the iceberg.53 All the evidence suggests that by the early twentieth century tens of thousands of middle-class Americans had adopted the practice of regularly venturing to the fields and forests in search of birds.

CONSTRUCTING OBSERVATIONAL NETWORKS

The tremendous growth of popular interest in birdwatching presented both opportunities and dilemmas for the small community of scientific ornithologists in the United States. Those ornithologists who served as leaders in the Audubon movement—and a significant percentage did—clearly welcomed the political clout thousands of birdwatching enthusiasts provided. Scientists, birdwatchers, humanitarians, and others in the Audubon coalition were remarkably successful in shepherding protective legislation through state assemblies and the U.S. Congress.54

Some scientists, like Julian Huxley, clearly hoped that birdwatchers might also prove effective (though subordinate) allies in the production of scientific knowledge. Scientific ornithologists in the United States had long depended on networks of collectors to provide them with the specimens necessary to conduct their research. As the nineteenth century came to a close, many ornithologists began arguing that networks of observers could also provide useful scientific data. One of the earliest American examples of a large-scale cooperative venture of this kind has already been discussed: the expansive observational network C. Hart Merriam began in 1883 as chair of the AOU Committee on Migration of Birds.55 The venture not only produced valuable information on the seasonal movement of North American birds, it also led to the funding of a federal agency that soon evolved into the Bureau of the Biological Survey.

Cooperative, observationally based bird study was also central to the mission of the Wilson Ornithological Club during its early years. The organization began in 1886 when an enthusiastic group of widely dispersed bird and egg collectors decided to form a correspondence society called the Young Ornithologists’ Association.56 Two years later the group changed its name to the Wilson Ornithological Chapter of the Agassiz Association after formally affiliating with Harlan Ballard’s national network of natural history societies. Although its original membership was scattered, the organization gradually became centered in the Midwest. At the same time it increasingly focused on cooperative studies of the living bird.57 In 1902 the group withdrew from the Agassiz Association and shortened its name to the more manageable Wilson Ornithological Club.58

Founding member Lynds Jones was central in guiding the club through its formative years.59 Born in 1865 to a large midwestern farming family, Jones developed a fascination for birds’ eggs by the age of seven. The discovery of Samuels’s Nests and Eggs of New England Birds and Coues’s Key to North American Birds coupled with encouragement from an older neighborhood boy and a schoolteacher fueled his youthful enthusiasm. By 1890 the burley, athletic Jones headed off to Oberlin College with an impressive egg collection (containing specimens from over 250 species) and a burning desire to turn his avocation into his life’s work. After graduation he stayed on at Oberlin to work as laboratory assistant and instructor in zoology while earning his master’s degree. In 1895 Oberlin officials gave Jones the opportunity to teach the first course in ornithology ever offered at an American institution of higher learning, a course he continued for more than three decades.60 Ten years later Jones earned his Ph.D. degree from the University of Chicago as well as a promotion to associate professor at Oberlin. He remained at his alma mater until forced to retire in 1930.

Jones served in nearly all the major offices for the Wilson Club, but he probably exerted the most influence as editor, a position he held for thirty-five years. Although his own interest in ornithology began as a collector, early in his tenure as Wilson Bulletin editor he began actively promoting field observation and cooperative research.61 For example, as early as 1897 Jones argued that real progress in solving fundamental questions about the geographic distribution, migration, and life history of North American birds could be achieved if the hundreds of young men who joined the Wilson Club faithfully submitted their observations to the various club committees established to compile and publish the information.62

That same year Jones’s most enthusiastic student, close personal friend, and kindred spirit, William Leon Dawson, argued that keeping systematic lists of species observed, even of common birds, would be highly “profitable” both to birdwatchers and to science.63 As chair of the Wilson Club’s Committee on Geographic Distribution, Dawson urged his fellow members to maintain several kinds of systematic records: “daily horizons,” lists of all the species found on a given day; “bird censuses” (sometimes called “censo-horizons”), lists of birds seen on a given day within a given area with numerical estimates of the abundance of each species; “annual horizons,” lists of all species located during a given year; and “life horizons” or “life-lists,” a cumulative record of all the species an individual had ever identified in the field. Although Dawson claimed it was “vulgar” to keep these lists merely for the sake of numerical comparison, both he and Jones continually stressed how their most recent counts stacked up against previous efforts in the field. They also repeatedly challenged their readers to better their records.64

Through their constant appeals in the pages of the Wilson Bulletin, Dawson and Jones not only recruited hundreds of observers, they also helped standardize the kinds of lists that birdwatchers kept. Soon birders across the nation were routinely competing to compile the longest lists of birds observed over the course of a day, year, and lifetime.65 These lists served many of the same functions as the skins and eggs gathered by an earlier generation of collectors: they provided a tangible record of accomplishment that could provoke pleasant memories, serve as a source of pride, and even potentially represent a contribution to science, but without the destruction of life that skin collecting necessarily entailed. From the beginning, competition seems to have been a crucial stimulus to bird listing, even for those devotees with no scientific aspirations.

Dawson and Jones urged birdwatchers not merely to compile local lists, but also to submit them to the Wilson Bulletin for publication.66 For example, in his early years as editor, Jones suggested numerous dates—New Year’s Day, April 1, Fourth of July, and others—when his readers ought to undertake daily horizons and censuses for submission to the Wilson Bulletin.67 He also published dozens of his own bird counts, including an extensive list he and Dawson compiled during a two-month, seven-thousand-mile whirlwind railroad tour through the West.68

Until the mid-1910s, local lists based on short-term observation formed a significant portion of the material printed in the Wilson Bulletin. It is hard for a modern reader not to get the impression that Jones’s fascination with listing was at least partly based on the fact that he was routinely short of the copy needed to keep his periodical afloat.69 But like many other ornithologists of his day, Jones also seemed convinced that birdwatchers’ lists possessed genuine scientific value, as long as they were compiled by competent and conscientious observers. Not until 1924, on the eve of his retirement as editor of the Wilson Bulletin, did he admit that North American ornithology had finally reached a stage in which the “mere enumeration of the birds .. . found in some political division” no longer represented “a contribution to knowledge” and no longer warranted “the cost of publication.”70

In 1900, three years after Dawson and Jones had first begun actively promoting horizons and censuses through the pages of the Wilson Bulletin, Frank Chapman proposed the first Christmas Bird Census in the pages of his newly launched Bird-Lore.71 Historical accounts of the event have stressed Chapman’s own version of the origin of the idea: the traditional Christmas Day hunt in which groups of hunters competed to kill the largest number of birds, with the results occasionally appearing in “leading sportsmen’s journals.”72 Chapman hoped a similar competitive spirit would motivate birdwatchers to venture out into the December cold, and to heighten the sense of rivalry, he promised to publish their results in Bird-Lore. Less appreciated as an additional source of inspiration for the idea is the original AOU migration network, which had proved a formative influence on Chapman when he first became interested in ornithology.73 Undoubtedly Chapman was also moved to action by one of Dawson’s recent requests. Although winter had traditionally been the time of the year when bird enthusiasts were least active in the field, in November 1897 Dawson urged readers of the Wilson Bulletin to “put in a day or two, this coming holiday vacation, taking the census of all the birds found in their village, or on the farm, or, if in the city, in the neighboring park.”74 As Dawson pointed out, obtaining accurate counts in a given area would prove much easier when most birds had migrated to warmer surroundings.

Although Chapman’s Christmas Bird Count began modestly, it soon developed into a major American ornithological tradition. Only twenty-seven birdwatchers responded to the original invitation to participate in the project, but with each subsequent year the number of observers, printed reports, species located, and total birds counted continued to mount.75 In 1909, less than a decade after the first census, the more than two hundred birdwatchers who took part in the Christmas count located in excess of 150,000 birds.76 Four years later the Canadian artist-naturalist Allan Brooks teamed up with that inveterate lister William Leon Dawson, then a resident of Santa Barbara, California, to produce the first Christmas count that surpassed a hundred species.77 By 1935 the Los Angeles Audubon Society (fig. 30) reported that a party of nineteen of its members located 170 species during its annual Christmas census.78 Four years later the total number of observers was rapidly approaching two thousand, the number of birds counted exceeded two million, and the number of census parties with over one hundred species numbered fifteen.79

Figure 30. Mrs. F. T. Bicknell in the field, 1918. Bicknell was president of the Los Angeles Audubon Society, one of the many organizations across North America that regularly sponsored teams of birdwatchers for the annual Christmas Bird Count.

The remarkable success of Chapman’s idea was due in part to birdwatchers’ efforts to become more systematic in the way they gathered their data. Lone census takers increasingly gave way to larger groups that could cover more territory and a greater variety of habitats. Relatively short forays gave way to longer surveys that could last as long as twelve hours or more. And haphazard wandering gave way to carefully orchestrated assaults in which rare birds were scouted out in advance and routes carefully chosen to maximize the number of species found on the day of the official census.80 At the same time, the Audubon societies and bird clubs that regularly sponsored census teams elevated the Christmas count into a major annual social event that was keenly anticipated by its many participants. For many, if not most, of those who joined in the annual event, companionship and competition seem to have been more important than contributing to science.

In an attempt to standardize the reports that flooded his office each winter, Chapman and his assistants gradually instituted several changes in the ground rules for the Christmas census. The original instructions stated that counts should be made on Christmas Day, a request that was routinely ignored. By the fifteenth year, census organizers disqualified counts not made between 20 and 30 December.81 Over the next three years the census was limited to a minimum of four hours and a maximum of twenty-four hours of observation, which was to be undertaken within an area of no more than fifteen miles diameter and within a specified seven-day period.82 Later the minimum number of hours in the field was raised again to six and then seven hours. Chapman also began requiring that “unusual records” be accompanied by a brief statement indicating the circumstances surrounding the identification, and he freely used his editorial discretion to suppress any records he considered dubious.83

As a result of these and other efforts, by 1922 Chapman was boasting that the Christmas census was a “well-established institution” with an “obvious . . . scientific value” that increased with each subsequent year.84 Other supporters were even more glowing in their evaluation of the undertaking, calling the annual event the “greatest cooperative ornithological project in North America” and proclaiming that “among all the activities of the amateurs, none is a greater contribution to science than the taking of the Christmas census.”85 However, given these and other claims about scientific utility, one of the remarkable things about the Christmas censuses was the paucity of publications they initially generated. By 1934, the year that the National Association of Audubon Societies purchased Bird-Lore from Chapman and took over the annual Christmas count, tens of thousands of hours in the field by thousands of volunteers had resulted in the publication of only two minor articles.86

BIRDWATCHING, BIRD BANDING, AND THE BIOLOGICAL SURVEY

While the Wilson Club and Frank Chapman were administering separate (though overlapping) birdwatching networks, the Biological Survey continued its cooperative migration studies. Like clockwork, in the spring and fall of each year officials sent out blank migration schedules to observers across the United States, and twice each year they received several hundred responses.87 However, little had been done to process the increasingly unwieldy mound of records since 1888, when Wells W. Cooke published a pioneering bulletin on the migration of birds in the Mississippi Valley.88 Prospects finally improved in 1901, when Cooke, “the father of cooperative study of bird migration in America,” received an appointment at the agency and the opportunity to continue the studies he had helped initiate in the 1880s.89

The son of a Congregational minister, Cooke was born in Massachusetts in 1858 but moved with his family to Ripon, Wisconsin, at the age of six.90 When he was twelve years old his parents bought him a shotgun, which he used to collect the heads and wings of local birds before learning the art of making proper skins. After graduating from Ripon College (A.B. 1879, A.M, 1882), he spent several years teaching native American children in Minnesota and Indian Territory. In the winter of 1881-1882 Cooke requested residents of the Mississippi Valley to send him lists of winter birds and dates of the first arrival of spring migrants in their local areas. The results of Cooke’s cooperative venture, published in Forest and Stream and Ornithologist and Oologist, inspired AOU founders to create a migration committee at its inaugural meeting in 1883, and Cooke was recruited to serve as superintendent of the Mississippi Valley division. Before finally landing a position as a government biologist, he worked for nearly two decades as an agricultural researcher at various universities.

Cooke entered into his new Biological Survey position with characteristic enthusiasm. To impose order on the mounds of notes gathered from volunteers over the previous fifteen years, he began entering each migration record on a separate index card. Scanning ornithological periodicals provided additional data for the burgeoning migration and distribution file. When writer’s cramp threatened to slow his progress, the right-handed Cooke simply taught himself to make entries with his left hand and then alternated between the two as needed. By 1910 the agency’s bird migration file contained more than six hundred thousand entries, which Cooke regularly consulted while preparing a long series of publications on migration routes and dates.91 The Biological Survey’s file also became an authoritative source of information on migration and distribution for other important publications, such as Arthur C. Bent’s Life Histories and the series of official AOU checklists of North American birds.

Beyond reinvigorating the Biological Survey’s migration monitoring program, Cooke also expanded the agency’s cooperative data collecting efforts. In 1911 he began conducting an annual spring census at his sister’s farm on the Virginia side of the Potomac River, a few miles from Washington. After passage of the Weeks-McLean (Migratory Bird) Act (1913) highlighted the lack of hard data on avian population levels, Cooke received permission to expand his investigation. He composed a widely circulated letter requesting qualified observers from across the United States to undertake exact counts of all the breeding birds on forty- to eighty-acre tracts.92 He was careful to point out that while anyone familiar with a handful of the most common birds could contribute to the survey’s migration studies, accurate census work required that a volunteer “be able to identify all the birds nesting on the area he covers, or be able to give a recognizable description of those he is unable to name.”93

The Biological Survey’s census program briefly flourished before falling into long-term decline. Despite good-natured ribbing from his skeptical colleagues, Cooke received reports from nearly two hundred cooperators in 1914, a number that increased to just over three hundred the following year. Following Cooke’s death from pneumonia in 1916, his daughter, May Thatcher Cooke, continued to administer the census network, but it languished. Finally, in 1937 the National Audubon Society started its own annual spring count, the “Breeding-Bird Census,” an institution that continues to flourish today.94

A competing cooperative project—bird banding—soon overshadowed the Biological Survey’s migration-monitoring network and its breeding bird census program. Although tagged birds had served as messengers since ancient times, it was not until 1899 that Christian Mortensen of Viborg, Denmark, began systematic banding of starlings as a method to study their migration patterns.95 Leon J. Cole, a recent graduate of the University of Michigan, was the first American to suggest the practice at a meeting of the Michigan Academy of Science held in March 1901.96 Apparently unaware of his European predecessors, Cole indicated that the idea had occurred to him after learning of the work of the United States Fish Commission, which had regularly tagged fish to track their movements.97

After several individual researchers began demonstrating the possibilities of bird banding, institutionalization quickly followed.98 Cole led a three-person committee that organized a small-scale banding program under the auspices of the New Haven Bird Club in the winter of 1907-1908. The organization sponsored a more ambitious program the following year, distributing five thousand marked metal bands, of which approximately one thousand were actually placed on the legs of nestling birds.99 The success of that effort encouraged Cole and other banding enthusiasts to organize a national society, the American Bird Banding Association (ABBA), at the annual AOU meeting in December 1909. Cole was elected president of the new organization by the thirty individuals attending the inaugural meeting of the ABBA. After he left the East Coast to accept a position at the University of Wisconsin in 1910, the society operated under the auspices of the Linnaean Society of New York from 1911 to 1919. At that point the Bureau of the Biological Survey accepted the ABBA’s records and began administering bird banding activities on the national level. A series of regional organizations stepped in to fill the void left by the demise of the ABBA, including the New England Bird Banding Association (1922; changed to the Northeastern Bird Banding Association in 1924), the Inland Bird Banding Association (1922), the Eastern Bird Banding Association (1923), and the Western Bird Banding Association (1925).100

Early bird banders tagged nestling birds with the hope that someone would eventually find and return the tag when the bird died or was killed. The fact that there was only a limited window of time when the birds where big enough to be banded and small enough to remain in the nest and that banders were dependent on the chance recovery of dead birds greatly limited the usefulness of the new technique. In 1914 S. Prentiss Baldwin came up with the idea of using government sparrow traps to catch and band various species on his property.101 During the next four years Baldwin banded over sixteen hundred birds at his summer estate in Gates Mills, Ohio, and his winter home in Thomasville, Georgia. In a paper published in 1919—which one of his admiring students called “one of the classic publications of all time” in ornithology—Baldwin publicized his revolutionary method of systematic trapping.102 Individual birds could now be recaptured multiple times at various locations, thereby tracing their movements over time. They could also be marked with special colored bands that could be observed from afar.

With Baldwin’s new method of trapping and sponsorship by the Biological Survey, bird banding began to take off in the United States in the 1920s. The agency hired the ornithologist Frederick C. Lincoln to administer the program, and by 1933 two thousand individuals across the nation had acquired the necessary federal license and tagged almost a million and one-half birds.103 Seven years later the total number of banded birds had reached nearly five million, with over three hundred thousand later captured, shot, or found.104 Bird banding gave a new meaning to the phrase “a bird in the hand,” and the data gathered by this extensive network greatly increased the knowledge of bird migration patterns in North America.

COOPERATIVE LIFE-HISTORY STUDIES

Besides keeping lists of species observed in a given area, a few more earnest birdwatchers also routinely kept records on the life history and behavior of the birds they encountered in the field. Well before Huxley published his plea for cooperation between biologists and birdwatchers in 1916, a handful of scientific ornithologists in the United States began to rely on networks of observers who monitored nesting dates, feeding habits, and breeding behavior of birds rather than rushing around trying to log as many species seen as possible. But as long as ornithology remained focused on systematics, only a few scientists seemed interested in taking advantage of the data these observers collected.

In their rush to construct a complete inventory of North American avifauna, scientific ornithologists had largely ignored the lives of the creatures they so eagerly collected, measured, named, and described. This rather narrow approach to ornithological research did not pass unnoticed by several more introspective contemporaries, one of whom commented in 1891: “The present generation of Ornithologists have been too busy in hunting up new species and in variety-making to study the habits of birds with equal care and diligence, and it is to Wilson and Audubon and Nuttall that we are chiefly indebted even at this day for what we know of bird-life.”105

Scientific ornithology’s focus on collecting was reinforced by the Gilded Age tendency to view specimens as commodities and by the early pattern of professionalization within the discipline of ornithology. Until the expansion of employment opportunities during the early twentieth century, museums provided the best hope for those who wished to pursue a vocation related to their interest in birds. However, museum administrators from this period generally expected their curators and collectors to return from expeditions laden with specimens to fill their exhibit halls and study collections, not merely with less tangible (and, in the eyes of many, less valuable) observations. For example, in a series of letters in 1890, shortly after joining the staff at the American Museum of Natural History, Frank Chapman complained to William Brewster of the constant pressure to collect he felt whenever in the field on behalf of his employer:

This miserable collecting. It is the curse of all higher feeling, it lowers a true love of nature through a desire for gain. I don’t mean a specimen here and there, but this shooting right and left, this boasting of how many skins have been made in a day or a season. We are becoming pot-hunters. We proclaim how little we know of the habits of birds and then kill them at sight. . . . Collecting, we have at the end of the day some tangible result to show for the day[’]s work. . . . The American Museum desires specimens, not notes.106

Of course, research on living birds was not entirely ignored. Curiously, until the early twentieth century, oologists were the members of the larger ornithological community with the strongest interest in life history studies. Though voracious collectors themselves, oologists tended to escape the preoccupation with nomenclature and classification that had gripped their skin-collecting colleagues. Moreover, merely through the process of gathering eggs, they learned a great deal about the lives of birds, including many facts that remained unknown to the average skin collector (e.g., when and where a species bred and the average size of a brood). It was a relatively small step from being tangentially concerned with such basic information as an integral part of the process of securing eggs and nests to a more focused investigation of the lives of the birds that produced these objects.

The close connection between oology and the study of the life histories and “habits” of birds is best demonstrated through a series of ornithological publications issued under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution. In 1857 Thomas Mayo Brewer, the Boston physician, publisher, and oologist, completed the first of several projected volumes of North American Oology.107 As the title suggested, Brewer’s treatise contained detailed descriptions and beautiful lithographs of North American birds’ eggs. However, it also included a great deal of information on the breeding ranges and habits of birds gathered from the earlier publications of Nuttall, Wilson, and Audubon, as well as observations based on his own and several “co-laborers”’ experiences in the field.108 Although Brewer continued to solicit donations of nests and eggs for ensuing volumes in the series, the work was abandoned, ostensibly due to the high cost of the illustrations.109

The Smithsonian series was begun anew in 1892, when Charles E. Bendire, an army surgeon who began collecting eggs in the late 1860s as a way to relieve boredom on frontier outposts, issued the first volume of his Life Histories of North American Birds.110 As with Brewer’s earlier book, much of Bendire’s data was culled from the standard ornithological texts, but he also relied heavily on his own investigation in the field as well as an extensive correspondence network.111 Although Bendire’s accounts tended to be much more detailed and original than Brewer’s earlier work, the focal point of the work remained the illustrations, beautiful chromolithographs of eggs produced under Bendire’s supervision from watercolors by John L. Ridgway.112 Bendire completed a second volume for the series in 1895, before succumbing to nephritis two years later.113 His successor, the wealthy egg collector William L. Ralph, continued to work on the project but died in 1907, before completing any additional volumes.114

Three years later, Arthur Cleveland Bent, a cotton machinery manufacturer, electrical utilities owner, and devoted oologist from Taunton, Massachusetts, approached Smithsonian Secretary Charles D. Walcott with a proposal to complete Bendire’s series.115 No doubt the success of several Wilson Club cooperative projects helped inspire the forty-four-year-old Bent. For example, in 1895 and 1900 Frank L. Burns had published lengthy life-history monographs on the crow and the flicker based largely upon data gathered by fellow Wilson Club members.116 More recently Frank Chapman had initiated an even more ambitious cooperative life history venture. In 1904 Chapman requested readers of Bird-Lore to begin systematic observation of the various species of warblers for a book he was contemplating. In his call for aid Chapman had proclaimed that “cooperation” was “the watchword of bird study,” the key to success of Bendire’s Life Histories, and absolutely crucial to gain “anything approaching adequate biographies of even a single species.”117 Over three dozen observers, including several well-known ornithologists like William Brewster, W. W. Cooke, and Lynds Jones, contributed field notes for Chapman’s Warblers of North America, published in 1907.118

Soon after he began negotiations with Smithsonian officials in 1910, Bent received authorization to resume work on Bendire’s project. A businessperson with a strong work ethic and highly developed organizational skills, Bent was thorough and meticulous in his research. For example, he organized the life history data for each species in a uniform sequence: “spring migration, courtship, nesting habits, eggs, young, sequence of plumages to maturity, seasonal molts, feeding habits, flight, swimming and diving habits, vocal powers, behavior, enemies, fall migration, and winter habits.” And in a move that signaled an increasing break from the strong oological orientation of earlier volumes, by the third installment of his series (published in 1922) Bent discontinued the practice of including color egg photographs in his work, illustrations that he had earlier considered as central to the project.119 What Bent had originally believed would take six volumes to complete when he began work on his Life Histories in 1910 had mushroomed into twenty volumes by the time of his death in 1954.120 Three additional volumes in the series were later completed under the supervision of the Harvard-trained ornithologist Oliver L. Austin, Jr.

Although Bent ranged far and wide and spent thousands of hours in the field gathering material for his life history series, from the start he recognized that the job was too big for any single individual to complete.121 In his initial correspondence with Walcott, he indicated that he hoped to follow the same “general plan adopted by Maj. Bendire, making the work largely cooperative and adding such original material as I could furnish.”122 To recruit contributors, Bent mailed out countless circulars and issued repeated pleas in ornithological publications.123 The favorable initial response encouraged Bent to continue the ambitious project. Over 150 individuals contributed eggs, notes, and/or photographs for the first volume, which was published to wide acclaim in 1919.124 By the time the final volume was published over fifty years later, the total number of contributors reached more than eight hundred.125

Although long out of date, for decades the Bent series has remained a starting point for serious research on the life history of North American birds. It is also a project that was inconceivable without the eyes and ears of birdwatchers across the North American continent who shared their observations.

THE PROBLEM OF SIGHT RECORDS

While scientists generally welcomed birdwatchers into observational networks, they repeatedly expressed concern when these same individuals began to independently publish sight records of birds outside their well-established ranges. Scientists had long depended on networks of collectors to provide them with skins needed to document new species and their ranges. With the exception of those apparently rare cases of fraud, the bird skins that collectors submitted were considered valuable regardless of who actually gathered the specimen. However, by their very nature observations were subject to countless vagaries and a great deal of individual interpretation. Depending on a number of factors, ranging from the conditions under which a sighting had been made to the experience and reliability of the observer, a proposed record may or may not ultimately prove accurate and, hence, useful to science. The possibility of errors was further heightened since birdwatchers routinely competed to produce the longest list of species viewed in a given period of time.

The first instinct of most scientific ornithologists, then, was to reject records based on sight alone. Their concern was ultimately based on a decades-long struggle to forge ornithology into an autonomous scientific discipline and profession.126 Consistent with that ongoing campaign, American ornithologists generally demanded that published claims about the existence or geographical distribution of any bird form be documented with a carefully collected, accurately labeled, and permanently preserved skin. This was particularly true when it came to the identification of subspecies, which were often based on differences in size or coloration that were so minute they could only be detected by careful examination of the specimen in hand, and then only when it was compared with an extensive series of similar forms. For an ornithological community that firmly believed in shooting first and answering questions later, sight identification of subspecies and most species seemed out of the question.127

The strong emphasis on specimen collecting and systematics was also reinforced by the pattern of professionalization in North American ornithology. As I have already suggested, until well into the twentieth century, only a few paid positions were available to research-oriented ornithologists, and most of these were curatorships at metropolitan natural history museums. Even if they were interested in pursuing behavioral and life history studies that did not require specimen collecting, the ornithologists who held these positions felt pressure to spend their time in the field amassing as many new specimens as possible, not collecting notes on their observations.

Their research agenda and their institutional location suggested that scientific ornithologists would be suspicious if not overtly hostile to sight records. In fact, scientists began to protest such records even before the first field identification guides had been published or the first Audubon societies organized. In 1883 the Ornithologist and Oologist published a brief article suggesting that field glasses might be used to identify birds without actually collecting them. An anonymous reviewer for the Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club fired back:

It is to be hoped that this method will be reserved for those “who have no wish, strictly speaking, to become ornithologists or oologists,” and that observations made by those who have “become acquainted” with birds in this way will never be put into print as a contribution to ornithology.. . . Watching birds through a field glass as a pleasant amusement we would not discourage, but as a method of identifying birds by novices, we do not know of a more excellent illustration of “how not to do it.”128

The exchange set the tone for the protracted battle that followed. As members of the birdwatching community entered a growing number of sight records into the ornithological literature, scientific ornithologists grew increasingly vocal in their opposition to the practice. For example, in 1902 William Brewster cosigned a letter to the editor decrying the fact that too many careless sight records had been appearing in the Auk.129 He concluded his protest with the suggestion that “no record of a bird merely observed, where there is any chance for error, be accepted, unless the observer be well known to the editor, or to some ornithologist of standing and judgment, who will vouch to the editor for the accuracy of the observer.”130 Over the next several decades, scientific ornithologists frequently repeated Brewster’s suggestion that the so-called personal equation be considered when evaluating sight records, though as the size of the birdwatching community continued to increase, this criterion became increasingly unmanageable in actual practice.131

Four years after his Auk letter, Brewster published Birds of the Cambridge Region (1906), a long-awaited book that was immediately hailed as a “classic in the annals of faunistic ornithology.”132 In the preface to his book Brewster argued that, with few exceptions, records of birds in localities outside their known range ought to be ignored unless established by “actual specimens . . . determined by competent authorities.”133 For Brewster and most of his scientific colleagues, mere observation of a living bird established nothing “more than possible or probable occurrence of the species in question—according to the weight and character of the evidence.” The only time Brewster was willing to suspend his deeply felt suspicion of sight records was with easy-to-recognize species—like the turkey vulture, swallow-tailed kite, and the cardinal—but only when they were reported by reliable ornithologists known to have had previous familiarity with these particular species in life.

That same year, 1906, Frank Chapman proposed another set of criteria by which to judge when sight records of birds observed outside their normal range might be considered worth publishing. Chapman argued that in some cases the standard that most “professional ornithologists” demanded—a captured specimen—resulted in unnecessary destruction of life as well as the loss of valuable information concerning the specimen in question. As an example of what might go wrong if collecting were pursued too exclusively, he pointed to the case of Brewster’s warbler, which William Brewster had named, described, and published as a new species in 1876 based solely on morphological data obtained from study skins. It was not until decades later, when ornithologists began systematically observing the bird in the wild, that they finally discovered that Brewster’s warbler was actually a hybrid between two distinct species: the gold-winged and blue-winged warblers.134 Here was a clear case where the practice of shooting first and asking taxonomic questions later had kept scientific ornithologists in the dark for far too long. On the other hand, Chapman pointed out that even the most careful and experienced ornithologist had occasionally made errors in field identification that only became known when they subsequently collected the specimen in question.

Given these considerations, when should observations by the “opera-glass student” be accepted? Chapman offered a widely adopted set of criteria by which to judge the merit of sight records:

(1) Experience in naming birds in nature, and familiarity, at least, with the local fauna. (2) A good field- or opera-glass. (3) Opportunity to observe the bird closely and repeatedly with the light at one’s back. (4) A detailed description of the plumage, appearance, actions and notes (if any) of the bird, written while under observation. (5) Examination of a specimen of the supposed species to confirm one’s identification.135

Even if all these requirements were fulfilled, Chapman argued, the validity of field identifications would “depend on the possibility of the occurrence of the species said to have been seen.” Sight records of birds distant from their normally understood range should be rejected, even if all of the above conditions could be met.

Although long a promoter of birdwatching, over the next few years even Chapman grew increasingly impatient with the fantastic records that were constantly submitted to him as editor of Bird-Lore. By 1909 he had further hardened his position on the issue of sight records by summarily rejecting them whenever the bird in question was even slightly beyond the normal limits of its known range. So-called records of occurrence were a permanent part of the history of a given species and hence represented an important “contribution to the science of ornithology.” The evidence upon which scientific records were based needed to be available for subsequent verification. The only way this could be accomplished, Chapman concluded, was to produce “the specimen on which the record was based.”136 While continuing to promote birdwatching as a valuable recreational activity, a means to recruit conservationists, and a method for gathering information on the seasonal movement of birds, Chapman had clearly moved into the camp of those who argued that scientific research in ornithology often demanded resort to the collecting gun.

Although the issue refused to disappear entirely, after the first two decades of the twentieth century several factors converged to diminish the controversy over sight records. First was the increasing difficulty in securing legal authorization to collect birds. Although the protective legislation the Audubon movement pushed through most state legislatures generally included a provision allowing for scientific collecting, many of the officials charged with enforcing those laws were reluctant to issue the necessary permits. A few officials refused to sanction any collecting at all. Some ornithologists simply ignored these legal restrictions and continued to collect just as they had always done in the past. However, the overall effect of this legislation was to make it much more difficult to meet the scientific ornithologists’ demand that a specimen be taken to verify claims about the existence of a bird form beyond its previously established range.

At the same time that many state officials moved to restrict collecting, several scientists worked to improve techniques of field identification. The individual who did more than anyone else to make the practice more certain and acceptable was Ludlow Griscom.137 From a young age he had developed an interest and proficiency in field identification as well as a strong resolve to become a professional ornithologist. After graduating from Columbia University in 1912, Griscom enrolled in the master’s program at Cornell and became the first in an extensive line of graduate students who studied ornithology under Arthur A. Allen. His master’s thesis was on the field identification of ducks, geese, and swans of the eastern United States.138 Following graduation, he spent a decade working under Frank Chapman at the American Museum of Natural History before accepting a post as assistant curator at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. His scientific research centered on more traditional avian systematics, but throughout his life, Griscom continued to work on refining his field identification techniques, and he enjoyed regular birdwatching outings.

Griscom firmly believed that even though “amateur” bird students had generally relinquished the practice of collecting, they still had a great deal to offer scientific ornithology. His first major paper on the subject, “Problems of Field Identification,” published in the Auk in 1922, claimed that the list of birds “practically impossible” or “very difficult” to identify in the field by a properly trained observer was very small and rapidly shrinking.139 Barring physical defects that might impair an individual’s ability to see or hear properly, Griscom continued, virtually anyone could become a trustworthy field observer, even if they pursued the activity “merely as a hobby.”140 In a characteristically flamboyant fashion, Griscom provided the strongest endorsement to date of the validity of sight identification.

Within the next year Griscom published his Birds of New York City Region, a guidebook that embodied his extensive knowledge of the avifauna of the region and his commitment to promoting rapid identification of birds based on characteristic, easy-to-recognize field marks.141 One reviewer noted that the appearance of Griscom’s book heralded the beginning of a new epoch: “In cutting away from many traditional requirements of the last generation” (i.e., the bird in hand as verification of records), Griscom had helped to forge a “new ornithology.”142 Griscom and his work also became the inspiration for the Bronx County Bird Club, a small but active group of young enthusiasts who regularly birded around the environs of New York City in the 1920s and 1930s and who later went on to distinguished careers in field ornithology.143 One member of the group was Roger Tory Peterson, who has declared that “Griscom was our God and his ‘Birds of the New York City Region’ our Bible. Every one of us could quote him chapter and verse.”144 Peterson has also acknowledged the formative role that Griscom’s field mark identification techniques played in the creation of his legendary Field Guide to the Birds, which was first published in 1934 and has since sold over three million copies.145

As the century wore on, scientific ornithologists grew more tolerant of Griscom’s identification techniques and sight records more generally. An additional reason for this softening on the issue was the series of fundamental changes that the field of ornithology was experiencing.146 One of the most far-reaching transformations was the emergence of graduate education in ornithology during the 1920s and 1930s. Newly established graduate programs produced a new generation of bird students who were more extensively and broadly trained than their predecessors, interested in a much wider variety of research problems, and qualified to begin careers in many newly emerging positions, ranging from wildlife managers to university professors.147 Freed from the narrow methodological and institutional limitations of the previous generation, graduate-trained ornithologists broadened the boundaries of ornithological research into new areas—like ecology and behavioral studies. In pursuing these new research agendas they regularly practiced field identification, and they generally seemed more tolerant of the sight records of others.

Yet even with restrictions on collecting, improvements in field identification techniques, and the expansion of ornithological education and research, the controversy over sight records refused to disappear entirely. As late as 1928, Biological Survey ornithologist Frederick C. Lincoln was still arguing that the only valid evidence for adding a new species to the list of given region was the “preserved specimen with all the data attached.”148 Of course, Lincoln’s claim was nothing new, but the response from two of the major technically oriented ornithological journals in the United States was. In their discussion of Lincoln’s article, reviewers for the Auk and the Wilson Bulletin agreed that Lincoln’s uncompromising rejection of all records not substantiated by a preserved specimen failed to take into account the profound changes that had occurred in the field of ornithology over the past few decades. While sight records still needed to be carefully evaluated to take into account “the record and ability of the observer,” they certainly ought not be rejected out of hand.149 Nearly two decades later, another Biological Survey ornithologist, W. L. McAtee, was still trying to make the case that scientific ornithology needed finally to relinquish its “specimen fetish.”150

PALMER’S QUALMS

By the turn of the century, birdwatching had developed into an important leisure activity that tens of thousands of middle- and upper-class Americans regularly enjoyed. For most of those who ventured out to the nation’s fields and forests in search of wild birds, birdwatching was primarily a form of recreation, a temporary escape from the hustle and bustle of an increasingly urban-industrial society and a chance to renew a deeply satisfying aesthetic and emotional bond with members of the feathered kingdom. For some, the lure of the list—the competition to produce the longest list of species viewed in a given day, during a particular season, or over a lifetime—provided additional incentive to pursue the popular activity.

A small subset of birdwatchers was also interested in contributing to the growth of the science of ornithology. With their eyes and ears spread across the vast North American continent, serious bird observers represented valuable potential allies in scientists’ efforts to map out the precise distribution and migration patterns of North American birds. Scientists hoping to take advantage of this potential were among the strongest promoters of birdwatching and the most active organizers of observational networks. Yet, as I have shown, scientific ornithologists did not always welcome the contributions of birdwatchers, particularly when they claimed to have discovered species and subspecies beyond their well-established ranges. In this crucial respect the rise of birdwatching represented yet another point of tension between scientific ornithologists and the broader community of bird enthusiasts.

While the proliferation of sight records provoked frequent comment, rarely did scientific ornithologists complain publicly about the distribution and migration data that participants in birdwatching networks provided. One of only a handful examples occurred when T. S. Palmer, Biological Survey staff member and longtime secretary of the AOU, criticized a single-day bird count from the Santa Barbara area that William L. Dawson published in the Condor in 1913: “It is questionable whether the best results are obtained by making a continuous wild rush between daylight and dark from one good bird locality to another, identifying and recording subspecifically, every note and every glimpse of feathers, in the sole effort to secure as large a list of species as possible.” Yet even Palmer did not reject the idea of censuses made by “several persons in a definite area, where each could take time to cover his territory thoroughly and follow up and observe the various birds.” In fact, he encouraged cooperative observational studies so long as contributors worked with foresight and care: “Let us have more bird horizons . . . made without recourse to automobiles and trolleys, omitting all doubtful species, with more attention given to the relative abundance of the common birds, and with less anxiety to record the largest number of species observed by one individual.”151 Like many ornithologists, Palmer was concerned that the race to compile the longest lists would inevitably lead to error.152

Yet while Palmer and other ornithologists were clearly concerned about minimizing the possibility of error, they recognized that the contribution of birdwatchers was crucial to large-scale migration and census studies. After all, North America is a vast continent, filled with more than seven hundred avian species, most of which move seasonally. No single individual, no matter how competent or earnest, could hope to begin adequately covering so many birds and so much territory in a single lifetime, and there were not yet enough scientific ornithologists able (or willing) to engage in the kind of large-scale cooperative projects that Chapman, Cooke, Bent, and others envisioned.

Necessity was not the only reason that Palmer and other scientists generally accepted the observations provided by birdwatchers with such a wide variety of motivations and abilities. Scientific ornithologists recognized that they were the ones who largely dictated the terms of interaction with the individuals who joined their observational networks. They not only established and enforced the ground rules for how acceptable observations were to be made, but also interpreted the data submitted. Under this arrangement, scientists could and did routinely reject any records that seemed suspect for whatever reason. Because of this ability to police volunteers and control data, scientists welcomed contributions to observational networks even as they railed against independently published sight records, which they perceived as a threat to their authority.