FIVE • The Spiritual Feminine in New Testament and Patristic Christianity

The Christianity that grew to be the dominant, or orthodox, churches, whose scriptures were canonized in the New Testament, developed parallel to and often intertwined with the gnostic forms of Christianity discussed in the previous chapter.1 The antignostic church fathers of the late second century, such as Irenaeus and Tertullian, made a forceful effort to separate from and eject gnostic Christians. They also worked to canonize, as the original and true “deposit of faith,” those early Christian writings that enshrined the views of what was then becoming the established church. The feminine aspects of God, as well as the leadership of female disciples, became greatly eclipsed in these dominant forms of Christianity, although significant traces of female symbolism for God, the soul, and the church remained, ultimately becoming channeled into Mariology. This chapter will trace the main lines of this development.

WISDOM IN THE NEW TESTAMENT

The Christians who shaped the stories, hymns, and sayings of Jesus that lie behind the canonical New Testament were reflecting on what for them was the decisive event in salvation history: the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. His teachings had gripped and transformed their lives, but he had been rejected by the dominant forms of Judaism and crucified by the Roman imperial powers as a dangerous popular leader. Yet the disciples of Jesus felt themselves renewed in their faith by his resurrection, overcoming the power of death meted out by the rejecting authorities. In this renewed power, they were to continue to preach his name as redemptive.

What were the sources for reflecting on the theological meaning of Jesus? Two major complexes of Jewish tradition provided the sources for this reflection: apocalyptic messianism and Wisdom literature. These two traditions had already partly mingled in late Sapiential literature, such as the Wisdom of Solomon, and the writings of the Qumran community.2 Sapiential literature provided these early Christians with the narrative of God's self-expression, Wisdom coming forth from God in the beginning, an agent with God in creating the cosmos, through whom the cosmos is sustained, providing the order of creation, and filling it with divine presence. Wisdom descends to earth, seeking disciples, and finds a home in God's elect people. Their teaching, the Torah, is the earthly manifestation of Wisdom. She offers spiritual nourishment, imaged as food and drink, to those who come to her; but she also is rejected, misunderstood by the wise and offered to the “simple.” This was the mythic narrative of the Jewish teachers whose schools sought to shape young men in the exemplary life of the Jewish people.3

A second narrative pointed to the messianic events of a coming vindication of the Jewish people against their oppressive enemies, the empires and rulers of the Persian and Greco-Roman worlds. God would intervene through his elect son, the Messiah, who, with angelic powers, would overthrow the oppressive empires, which represented cosmic powers that had separated from and were hostile to God and God's people. The Messiah would be a new Son of David, who would reestablish on a final basis the salvific promise of the Davidic monarchy. Or, even more, there would come a Son of Man, an angelic expression of God's people, Israel, who would overcome not only evil but also finitude and would inaugurate a redeemed cosmos beyond both sin and death.4

The fusing of these two narratives into a unified story to reveal the secret identity of Jesus, the crucified teacher of the Christian movement, happened remarkably early, apparently within two decades after Jesus's death.5 The early development of a cosmic Christology that fused Wisdom protology (theory of the “first things”) and messianic futurism inspired some New Testament scholars to suspect that Jesus must have in some way identified himself both as the final prophet/messianic envoy and as the expression of divine Wisdom.6 Others question the validity of tracing these ideas to Jesus himself, given the unprecedented nature of this fusion, not to mention how unlikely it would have been for a Jewish teacher of the early first century CE to claim to represent either or both in his person.7 What is unquestionable is that both narratives formed the matrix of the earliest Christian reflection on the theological identity of this teacher, who had been loved by his followers and who had been snatched from them by a cruel public death.

Cosmological Christology is represented in many fragments of hymns found in Pauline and Deutero-Pauline writings—for example, Philippians 2:6–11; Colossians 1:15–20; 1 Timothy 3:16; and Ephesians 2:14–16; as well as Hebrews 1:3; 1 Peter 1:20, 3:18, 3:22; and John 1:1–11. These hymnic fragments express elements of the cosmic-eschatological vision through which the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus are interpreted.8

Philippians 2:6–11 contains a full expression of this vision. Here, we start with protology; move through descent to earth and, finally, death; and then move to exaltation and enthronement as the heavenly Messiah who has subdued the cosmic powers. In this hymn, Christ Jesus is the one who originated in heaven, sharing the form of God but choosing to descend to earth, emptying himself of divine power to “take the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men,” humbling himself to the point of sharing the human condition of death. “Therefore God has highly exalted him, bestowing on him a name above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow in heaven, and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.”

Colossians 1:15–20 focuses on protology, alluding to the eschatological side briefly in elements that may have been added to what was originally a Wisdom hymn. Here, it is said that Christ “is the image of the Invisible God, the first born of all creation.” In him, all cosmic powers in heaven and on earth were created; “all things were created through him and for him. He is before all things and in him all things hold together.” The idea that he is the unifying power of the cosmos has been edited to make him the “head of the Church” and to identify the future reunification of the cosmos as having come about through the blood sacrifice of the cross:9 “He is the beginning, the first born from the death, that in everything he might be preeminent. For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile all things to himself, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace through the blood of his cross.”

Hebrews 1:1–4 intertwines protology and eschatology with quick strokes. It begins by positioning Jesus as part of the line of prophets through which God has spoken to his people in the past. But he is more than a prophet; he is the divine Son, who is both creator and redeemer. “In these last days he has spoken to us by a Son, whom he has appointed heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. He reflects the glory of God and bears the very stamp of his nature, upholding the universe by his word of Power. When he made purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of majesty on high, having become as much superior to the angels as the name he has obtained is more excellent that theirs.”

Cosmic Christology claims to deliver believers from the ruler of the demonic cosmic powers or to restore these cosmic powers to their proper place in submission to God. These ideas lie in apocalyptic thought, in which the oppressive empires on earth are seen as earthly manifestations of angelic powers that have revolted against God. Thus, Christ in his messianic work conquers these powers and restores the cosmos to its proper order and harmony. The claim that entering into the redeemed community and future restored cosmos, proleptically present in the church, liberates Christians from the domination of these hostile cosmic powers parallels the claim made in the Isis cult (see chapter 4) that Isis will free the initiate from the rule of fate.

Cosmic Christology is explicitly lacking in the synoptic gospels, which led an earlier generation of New Testament scholars to assume that it developed at a later period.10 But its existence as tradition from which Paul draws indicates its early development. The Q tradition (Q stands for “source,” which refers to common traditions in the synoptic gospels), from which Matthew and Luke draw, had already made a connection with Wisdom, seeing Jesus as a prophet-teacher of Wisdom.11 Traces of the female personification of Wisdom are evident in several Q passages, in which Wisdom is said to have “sent prophets and apostles” whom the Jewish teachers have rejected and killed (Luke 11:49). Jesus weeps over Jerusalem as a “mother hen” who would “gather her brood under her wings” (Luke 13:34). Jesus's unconventional table fellowship with sinners is justified in Matthew 11:19 by identifying him as Wisdom herself: “Yet Wisdom is justified by her deeds.”12 Luke 7:35 probably preserves an earlier form of this saying, in which Jesus is portrayed as one of the children of Wisdom rather than as the unique incarnation of her: “Yet wisdom is justified by all her children.”13

In the Gospel of John, we find the protological drama fused with the story of Jesus as teacher and revealer of the higher divine life, which his followers are invited to enter in order to share in the eternal life of God's presence.14 John's prologue presents Jesus as the divine Word that was with God and was God “in the beginning.” It then moves to reveal the Word as creator and sustainer of the universe, the source of life and knowledge for all creatures. He enters the world and is rejected by those to whom he came but is the source of eternal life for those who accept him:

All things were made through him and without him was not anything made that was made. In him was life and the life was the light of men. . . . He was in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world knew him not. He came to his own home and his own people received him not. But to all who received him, who believed in his name he gave power to become children of God, born... of God. (John 1:3, 9–13)

This Johannine drama of the divine Logos as creator, revealer, and redeemer is then told through revelatory stories in the life and teachings of Jesus.15 He teaches in paradoxical symbols that are misunderstood by those who have only material eyes, but that reveal him as the incarnation of redemptive life for those who receive them with the eyes of faith. Like Wisdom, he feeds and nourishes, gives saving bread and drink, offers the waters of eternal life, and speaks in the revelatory “I am” language with which Wisdom praises herself. Although rejected by those under the powers of darkness, he finds a home in a small embattled community of believers. These he makes “friends of God and prophets,”16 through whom there is immortal life and to whom he sends the power of the Paraclete after he returns to his heavenly home above.

Yet the shift of language from Wisdom (sophia) to Word (logos) effectively eclipsed the female personification of this creator-revealer-redeemer. The roots of this masculinization of what in Jewish tradition was a female personification of God have been hotly debated in contemporary scholarship. Some view Philo, who insisted that Wisdom was female only as a subordinate expression of a male God but was masculine in the work of creation and was represented on earth in the Logos, as a key source of this shift in grammatical gender.17 Another impetus may have come from the identification of Jesus not simply as child and prophet-teacher of Wisdom but as Wisdom incarnate—who, as a male, is he and not she.18 Perhaps also his identification as Messiah, always a male figure in Judaism, impelled this change of language from sophia to logos, whose male grammatical gender is more in keeping with both the maleness of Jesus and the images of the Messiah.

In Elizabeth Schuessler Fiorenza's view, this combination of Logos and Jesus as divine-human son of God allows the dominance of the fatherson language so evident in the Gospel of John in particular. The fatherson relation readily encapsulates both the male hierarchical relation between the Father and Son aspects of God and the male hierarchical relation of God to the human Jesus as the incarnation of the divine Son. This lineage is then continued in the Christian “sons” born to God through baptism. Female mediation, such as that found in the Jewish Wisdom tradition and developed in gnosticism, is thus eliminated in this “ortho-dox” relation of father to son on the interdivine level, recapitulated on the divine-human level.19

FEMALE GOD LANGUAGE IN THE WRITINGS OF CHURCH FATHERS

The identification of the roles of Wisdom with a masculine Logos-Christ largely repressed any development of a female personification of the divine, based on the figure of Wisdom, in the writings of church fathers. But the Wisdom literature of Hebrew scripture, including books such as the Wisdom of Jesus ben Sirach and the Wisdom of Solomon, was included in the Christian Bible. Patristic Christianity used the Greek Septuagint as the basis for its Old Testament, which included these later works.20 Thus, a female-personified Wisdom remained scriptural for Christians. This figure would be elaborated in later developments in medieval Latin Christianity and Greek Orthodoxy.21

The fatherson metaphor for the relation of God to the Word of God generally fixed the two poles of the Christian Trinity as male-male, but the Holy Spirit remained fluid. Imaged as a dove, it was not fixed in any gendered personification. An early stream of Aramaic-Syriac Christian tradition portrayed the Spirit as feminine. The Gospel of Philip sees the femaleness of the Spirit in a biological sense that precludes attributing Jesus's conception to the Spirit: “Some say Mary conceived by the Holy Spirit; they are mistaken; they do not realize what they say. When did a female ever conceive by a female? Mary is the virgin whom the forces did not defile.”22 It is not clear whether this view casts the Holy Spirit as a cosmic force alien to God, which would make such a conception a defilement of the virgin. In the Gospel of the Hebrews, the Holy Spirit is seen as Christ's mother and also the power that transports him to the mountain of his transfiguration. In this gospel, Christ says, “Even so did my mother, the Holy Spirit, take me by one of my hairs and carry me away unto the great Mountain, Tabor.”23

The most lush development of female images for the Spirit is found in the second-century Syriac hymns the Odes of Solomon.24 The language of these hymns is poetic, not philosophical, and explores a plurality of images for the believer's transformed life through communion with the divine. Feminine images cluster around the Spirit, as the Syriac word for spirit, ruha', is itself feminine.25 But the Father and the Word can also be imaged in feminine terms. Here, the source of the metaphors is not simply grammatical gender but the images themselves, such as milk and birth, that suggest the female activities of carrying a child in the womb, giving birth, and suckling.

God's Word as milk that a mother gives to a newly born child recalls Paul's use of this image in 1 Corinthians 3:1–2. But perhaps a more potent source for this image, which appears in the works of the Greek and Syriac fathers, is the baptismal practice of giving the newly baptized a cup of mingled milk and honey. This drink symbolizes not only the feeding of a newborn but also the image of paradise as a “land flowing with milk and honey,” which the believer enters through baptism.26

The symbol of the Word as milk appears four times in the forty-two Odes. The image of being fed with milk fosters metaphoric development that images God as breasted and suckling us. Thus, Ode 8.14 has Christ, speaking as the Wisdom-Creator of humanity, say, “I fashioned their members and my own breasts I prepared for them that they might drink my holy milk and live by it.” Ode 35.5 says of Christ, “And I was carried like a child by its mother, and He gave me milk, the dew of the Lord.” In Ode 40, the writer declares, “As honey drips from the honeycomb of bees and milk flows from the woman who loves her children, so is my hope upon Thee, O my God.”27

The most elaborate use of the milk metaphor is found in Ode 19:

A cup of milk was offered to me, and I drank it in the sweetness of the Lord's kindness. The Son is the cup and the Father is He who was milked and the Holy Spirit is She who milked Him. Because His breasts are full, and it was undesirable that His milk should be ineffectually released. The Spirit opened Her bosom and mixed the milk of the two breasts of the Father. Then she gave the mixture to the generation without their knowing and those who have received [it] are in the perfection of the right hand.

The Ode goes on to portray Mary receiving this divine milk and conceiving by it:

The womb of the Virgin took [it] and she received conception and gave birth. So the Virgin became a mother with great mercies. And she labored and bore the Son without pain because it did not occur without purpose. And she did not require a midwife because He caused her to give life. She brought forth like a strong man with desire and she bore according to the manifestation and acquired with great power.28

Such complex reversals of male and female images preclude taking these gender symbols literally. Mary can become a strong man in giving birth, while the Father has full breasts milked by the Spirit that gives life to believers and causes Mary to conceive.

The dove image of the Spirit also fosters metaphoric development. Thus, Ode 24 notes, “The dove fluttered over the head of our Lord Messiah, because He was her head, and she sang over Him and her voice was heard.” Ode 28 imagines the dove fluttering over a nest to feed her nestlings. The image then changes from a nest to a womb, in which the believer is carried and leaps for joy, as Christ leapt in his mother's womb (Luke 1:41): “As the wings of doves over their nestlings, and the mouths of their nestlings toward their mouths, so the wings of the Spirit over my heart. My heart continually refreshes itself and leaps for joy, like a babe who leaps for joy in his mother's womb.” The Spirit making music through us like a harp is also a favorite image, as in Ode 6: “As the wind moves through a harp and the strings speak, so the Spirit of the Lord speaks through my members and I speak through His love.” The Holy Spirit as a harp through which we praise God also appears in Ode 14.8.29

Christ can also appear as Virgin Wisdom, who calls her sons and daughters to her, recalling the image of Wisdom in Proverbs. Ode 33 contains this call: “However the perfect Virgin stood who was preaching and summoning and saying, O you sons of men return, and you their daughters return and leave the ways of the Corrupter and approach me. And I will enter into you and bring you from destruction and make you wise in the ways of truth.” The writer can speak of the Spirit as both giving rest and carrying him into the presence of God, where the sight of glory inspires these odes. Thus, in Ode 36: “I rested on the Spirit of the Lord and She lifted me up to heaven and caused me to stand on my feet in the Lord's high place before His perfection and His glory, where I continued glorifying [God] by the composition of Odes.”30

Although more rare, female imagery also appeared in the writings of the second-century Greek church fathers, particularly related to the metaphor that describes God's Word as milk that feeds us spiritually and hence compares God or Christ to a nursing mother. Clement elaborates at length on how both Christ and God feed us with milk as a mother does, observing: “The Father's breasts of love supply milk.” The medical idea of Clement's time that mother's milk was a curdled form of blood also leads him to a long disquisition on how Christ's redeeming blood is related to the milk by which he feeds us. Irenaeus also uses the milkbreast metaphor: “We being nourished as it were by the breasts of His flesh and having such a course of milk nourishment become accustomed to eat and drink the word of God.”31

The Syriac and Greek fathers are clear, however, that gender imagery for God in no way makes God either male or female. Gender images, like all other images (such as bird, water, fire), are taken from our bodily experience and applied metaphorically to God. Ephrem, a fourth-century Syriac father, speaks of such metaphors as garments that God puts on and takes off to make God accessible to our imagination. “God puts one metaphor on when it is beneficial, then strips it off in exchange for another. The fact that He strips off and puts on all sorts of metaphors tells us that the metaphor does not apply to His true being because that Being is hidden, he has depicted it by means of what is visible.”32

The fourth-century Greek church father Gregory Nyssa argues not only that God is neither male nor female but also that gender is ephemeral in humans. Our true nature is the spiritual nature by which we image God. This image exists equally in men and women and is not gendered. Gender is a temporary garb put on us in our historical existence, but it will be discarded in the resurrection. Women too can achieve the highest spiritual development and sometimes take the lead in relation to less developed male relatives. He occasionally speaks of God the creator as mother, while arguing that neither “mother” nor “father” refers to any literal gender in God. Thus, in his commentary on the Song of Songs, he writes:

No one can adequately grasp the terms pertaining to God. For example, “mother” is mentioned in place of “father” (Cant. 3.11). Both terms mean the same because the divine is neither male nor female (for how could such a thing be contemplated in divinity, when it does not remain intact permanently in us human beings either? But when all shall become one in Christ, we shall be divested of the signs of this distinction together with the whole of the old man). Therefore every name found [in Scripture] is equally able to indicate the ineffable nature, since the meaning of the undefiled is contaminated by neither female nor male.33

Gregory Nyssa understands the groom as Christ and the bride as the soul. The references to the mother of the bride he understands as God the creator: “All things have, as it were, one mother, the cause of their being.”34

The view that gender terms for God are mere metaphor, since God is neither male nor female, is echoed by Gregory Nazianzus (another fourth-century Greek church father) and Jerome. Gregory Nazianzus mocks the Arians for their literalism in imagining that using the male grammatical gender for God makes God literally male: “God is not male although he is called father.”35 Jerome remarks that the word for the Spirit is “feminine in Hebrew, masculine in Latin and neuter in Greek, to teach us that God is without gender.”36 Yet the Greek and Latin fathers follow the cultural pattern of using “femininity” to symbolize the lower passions and bodily nature, and masculinity to symbolize the higher intellectual and spiritual nature. They argue that both men and women have both capacities. Spiritually undeveloped men are womanlike, while spiritually developed women become “virile and strong.”37 But this interpretation of masculine and feminine suggests that male images are appropriate for God, while female images are not.

FIGURE 25

Feminine Holy Spirit between the Father and the Son, fourteenth century. Fresco in Church of St. Jakobus in Urschalling, southwest of Munich, Germany.

Augustine follows this tradition in identifying sapientia, or wisdom, as the higher or male part of the mind and scientia, or sense knowledge, as the female lower part of the mind through which the goods of the earth are administered. He uses this hierarchical gender symbolism to argue that divine Wisdom, although grammatically feminine and imaged as feminine in the Wisdom literature, is male. Male wisdom, not female sense knowledge, is the true image of God in humanity. This image of God is shared by both men and women, although women in their bodily nature image the lower nondivine reality. This insistence that masculinity images the incorporeal divine nature and femininity the bodily appetites means that, for Augustine, gender imagery cannot be used interchangeably for God. God has no “taint” of the feminine, and hence only male, never female, images are appropriate for God.38

This view seems to have had a determinative effect on the language used to describe God by the Latin and Greek church fathers after 400 CE, as the church councils hammered out the orthodox definition of the trinitarian God. At this time, feminine language in reference to God disappeared from the Syriac tradition.39 The lush treatment of the divine as a plurality of male and female beings in gnosticism had been rejected by orthodoxy since the late second century. Even occasional metaphorical use of mothering language for God, on the grounds that God was nongendered and all metaphors were partial, faded. Metaphorical masculinity became tied to intellect and divinity, while metaphorical femininity was linked to the nondivine world of sense knowledge and bodily nature. Nonetheless, medieval art occasionally portrayed the Spirit as female (fig. 25)

FEMININE SYMBOLS FOR HUMANITY: ECCLESIA AND ANIMA

Hebrew scriptures had depicted the relation of God and Israel as a troubled one, between a wooing and punishing husband and a rebellious wife. These writings had also imagined a time of redemption, when this relationship would become one of idyllic love. The rabbis had allowed the Song of Songs to be included in the canon as an allegory of this future time of perfected bliss. The Christian church inherited this nuptial metaphor and transferred it to the relation of Christ and Ecclesia (the church). For Christians, the church was the beginning of that eschatological bride in whom all sin has been banished. Christians were the children of the free woman, the heavenly Jerusalem; the Jews were the children of the slave woman, Hagar, whose children are to be cast out (Gal. 4:21–31). In 2 Corinthians 11:2, Paul speaks of the church he has gathered as a “pure bride,” whom he has betrothed to Christ and whom he does not want to be corrupted by heresy.

Bridegroom language for Christ is found in the gospels. In a question about fasting, the followers of Jesus who share common meals with him are referred to as the wedding guests who do not fast “as long as the bridegroom is with them.” When the bridegroom is taken from them, “then they will fast” (Matt. 9:15; also Mark 2:19, Luke 5:34–35). In the Gospel of John, John the Baptist is the friend who rejoices to hear the voice of the bridegroom, to whom the bride belongs: “He who has the bride is the bridegroom” (John 3:29). Such language also appears in Matthew: in the Kingdom of Heaven, ten maidens await the coming of the bridegroom, but only five keep their lamps supplied with oil and hence are ready to go in with him to the marriage feast when he comes (Matt. 25:1–10).

For the author of the Epistle to the Ephesians, the church is Christ's bride, redeemed by his sacrificial love “that he might sanctify her, having cleansed her by the washing of water with the word that the church might be presented before him without spot or wrinkle or any such thing that she might be holy and without blemish” (Eph. 5:26–27). Rather improbably, this sanctified relationship is then made a model for the relation of husbands and wives. In Revelation, the vision of a woman clothed with the sun, the moon under her feet, and a crown of twelve stars on her head (fig. 26), who labors and brings forth a “man-child” and flees into the wilderness to take refuge against the dragon (Rev. 12:1–6), is the new Israel, the church who births a messianic humanity. When all evil has been conquered by Christ, the heavenly Jerusalem is pictured as “coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (Rev. 21:2).40

Drawing on these New Testament interpretations of the marriage metaphor, Christians early began to write commentaries on the Song of Songs as an allegory of the nuptials of Christ and his redeemed bride, the church. Hippolytus of Rome developed the ecclesial meaning of the Song of Songs in his commentary in the second century.41 But it was the voluminous commentary by the third-century Alexandrian father Origen that would have the most lasting influence. For Origen, the Song of Songs points through the veil of allegory to two different aspects of the wedding between God and humanity: the wedding between Christ and Ecclesia (the church), and that between Christ and anima (the soul). Origen's commentary differentiates and parallels these two dimensions of meaning—the collective, historical meaning and the individual, personal meaning.42

FIGURE 26

Mary as the woman clothed with the sun, early fourteenth century. Monastery of Katharinental, Switzerland. (From Kyra Belán, Madonna: From Medieval to Modern [New York, NY: Parkstone Press, 2001])

Origen begins his commentary by seeking to banish from the reader's mind any attention to the lush eroticism of the actual text of the Song. For Origen, this sexual language is a mere external veil that conceals the true spiritual meaning. Only the spiritually mature who have overcome all sexual lust dare approach this text; those whose sexual appetites might be aroused by its language are not fit to read it. The love referred to in the Song is not bodily but spiritual. It is that higher Eros by which the soul is led upward to its communion with God.43

Origen then proceeds to extract a spiritual meaning for each phrase of the Song through a concatenation of texts from Hebrew scripture and the New Testament, read allegorically in the manner that had been established by the Jewish Hellenistic exegete Philo. Through this method, the poetry of the Song becomes a series of symbols pointing to the story of the church in her historical journey and eschatological fulfillment and also the journey of the soul to restored spiritual perfection. The bridal relation of Christ and the church does not begin with the historical Jesus; rather, it originates in the first calling of God's people, Israel. The story of the soul begins in heaven, before the fallen, bodily world.

God's choosing of Israel is described in Origen's commentary as the betrothal of an immature girl who is not yet ready for marriage. She receives from God the betrothal gifts of the Law and the Prophets to prepare her for her future groom, while she longs for his coming and their wedded bliss. In Christ, the bridegroom has come, but the full consummation of their love is still in the future. Then a new bride of Christ is brought in from among the Gentiles. She lacks these earlier betrothal gifts, and hence is more sinful, but now has become transformed and supersedes the unbelieving Israel (Origen's interpretation of the description of the bride as “black but beautiful”). Yet the redeemed bride of Christ is still harassed by demonic powers and surrounded by heretics who have distorted the faith. But very soon the returning Christ will overcome these enemies, and the church's communion with Christ will be fulfilled.44

The journey of the soul (anima) runs parallel to that of the church (Ecclesia), but in an individual and vertical trajectory. Although Origen did not develop this idea in his commentary, we know from his treatise De Principiis (On First Things) that he believed that souls were originally created as luminous intellectual spirits (logikoi) that imaged the divine Logos and formed the original divine pleroma with the trinitarian God. But these intellectual spirits turned away from God and fell into various levels of alienation from him. These levels of alienation were then organized into a hierarchically ordered cosmos, with some becoming planetary angels, others human souls, and others demons. The level of “fallenness” is expressed through various types of bodies, with the angels taking on fiery bodies; the humans gross, material bodies; and the demons dark, shadowy bodies.45

For Origen, the journey of the soul is a process of moral, intellectual, and spiritual learning, by which she gradually recovers her original spiritual nature and sheds the material body into which she has fallen. Origen sees his own catechetical school as an epitome of this journey. In such schools, the souls learn moral and natural philosophy, preparing them for higher mystical insights.46 These preliminary stages of education correspond to the Law and the Prophets in Israel's history as “betrothal gifts,” given in preparation for the wedding of the soul with her bride-groom, the heavenly Logos. This preparation includes moral discipline. The soul must learn to repress bodily appetites and free her true self from the lower world of the senses. As she achieves this spiritual maturity, she then is ready for the coming of the bridegroom—that is, the illumination of the soul by the divine Logos and its restoration to its original spiritual nature.47

In this account of the soul's journey, Origen follows a typical pattern of Platonic mysticism. The journey involves moral ascesis, or disciplining of the appetites and intellectual purification of the mind from sense knowledge, leading to intellectual illumination.48 There is no place for erotic feelings, even in a sublimated form such as we find in medieval mysticism (see chapter 6).49 The feminine imagery of the church and the soul as bride is employed only as a symbolic pointer to a nongendered, spiritual meaning.

For Origen, gender, like the body itself, is a secondary acquisition, taken on through the fall, but it will be discarded as the soul is restored to its true nature. Therefore, neither feminine imagery for the church and the soul nor masculine imagery for Christ as bridegroom has any counterpart in the spiritual world. They are conventions of human language but have no spiritual meaning. God, the Word of God, the church, and the soul are in their essential spiritual nature “neither male nor female.”50

Gregory Nyssa's commentary on the Song of Songs, written a century and a half after that of Origen, concentrates more exclusively on interpreting the text as an allegory of the soul's journey to God, although it also makes reference to the nuptials of the church with Christ. For Nyssa, neither God nor the soul has gender; the feminine image of the soul as bride and the masculine image of Christ as bridegroom are simply poetic forms adapted to our present finite life. Indeed, the young man exhorted to seek Wisdom in Proverbs is in the Song changed into a bride; while Wisdom, feminine in Proverbs, is the bridegroom—indicating the nonessential nature of gender imagery.51

For Nyssa, the soul made in the image of God is genderless, like God. Gender is acquired as part of the soul's fall into sin, taking on “coats of skin,” that is, the mortal body. But as the soul grows in spiritual life, it regains its original nature in union with God. At the resurrection, gender differences will be discarded; and the soul, united with a nongendered spiritual body, will grow “from glory to glory” in infinite imitation of the eternal nature of God, drawn by the power of love. In Nyssa's view, the erotic, gendered imagery of the Song is to be ignored. Its true meaning points to the journey of a nongendered soul to a nongendered God.52

Jerome, as noted earlier in this chapter, shares this view of God as neither male nor female. In his long letter to Eustochium, the teenaged daughter of his spiritual companion, Paula, Jerome vividly exploits the erotic language of the Song, all the while exhorting the young girl to guard herself not only from the presence of worldly companions but even from all thoughts that might awaken her bodily desires. Her relation to Christ as her true bridegroom must be guarded from any temptation to fall into physical relations with an actual man. The love language of the Song is transferred to the spiritual relation Eustochium should imagine herself to be having with Christ:

Let the secret retreat of your bedchamber ever guard you. Ever let the Bride groom hold converse with you within. When you pray, you are speaking to your Spouse. When you read, He is talking to you, and when sleep comes upon you, He will come behind the wall and He “will put His hand through the opening and will touch your body” (Cant. 5.4). You will arise trembling and will say, “I languish with love” (Cant. 5.8). And again you will hear His reply: “My sister, my spouse, is a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up” (Cant. 4.12).53

A late third-century treatise, the Symposium, also depicts female Christian virgins as the ideal type for this spousal relation to Christ. Drawing on Plato's Symposium, Methodius, the author, imagines a banquet in a paradisal setting, in which ten Christian women discourse on the superiority of virginity over marriage (although one of them warns that faithful marriage has not been ruled out in Christian times).54 Although Methodius uses this gathering of women to exemplify the highest Christian life, he shares a low estimate of “femaleness” itself. For him, maleness represents the rational part of the soul, whereas femaleness represents carnal sensuality. Women are prone to weakness, silliness, and fatuous conversation.55 Yet all these characteristics are belied by these Christian virgins, who have put off female weakness and have been transformed through chastity into types of spiritual purity and power.

For Methodius, sexual reproduction and even polygamy were allowed during the earlier era of human history when humans were spiritually immature. But virginity is now the ideal state of life, which points toward the redemptive era of incorruptibility that is dawning. In imagery drawn from Plato's Phaedo, chastity guides the chariot of the soul as it soars aloft into the heavens and glimpses the celestial world of immortality.56 Chastity both restores humanity to its original paradisal state before the fall and anticipates its restoration to this heavenly state.

Methodius also explores the church's virginal nuptials with Christ. The church is imaged as the true Eve, who is born from the side of Christ, the true Adam, as Eve was born from the side of the old Adam, an image also found in Tertullian's De Anima.57 Christ's passion on the cross is imagined as a spiritual counterpart to sexual ejaculation, through which Christ inseminates his spouse, the church. The church, in turn, bears many children to immortality in baptism:

So too the word “increase and multiply” is duly fulfilled as the Church grows day by day in size and in beauty and in numbers, thanks to the intimate union between her and the Word, coming down to us even now and continuing his ecstasy in the memorial of his Passion. For otherwise the Church could not conceive and bring forth the faithful “by the laver of regeneration” unless Christ emptied Himself for them too for their conception of Him, as I have said, in the recapitulation of his Passion, and came down from heaven to die again and clung to his Spouse the Church, allowing to be removed from His side a power by which all may grow strong who are built upon Him, who have been born of the laver and receive His flesh and bone, that is, of his holiness and glory.58

A different image of the church is explored in the second-century treatise the Shepherd of Hermas. Here, the church is portrayed more in the lineaments of Wisdom, as teacher, an image that would be carried over into medieval art (fig. 27). In a vision, the church appears to Hermas as an older woman in a shining robe with a book in her hand, who seats herself on a large white chair. Reading from her book, she reveals that the world was created from the beginning by God for the sake of the church.59 The church is the foundation and fulfillment of God's plan for creation (although the church is not credited, as Wisdom was, with being an agent in the creation). The church is a revealer of visions, a teacher of the right understanding of ethical discipline, which includes the possibility of a second forgiveness after baptism. The woman in the vision dictates messages to the leaders of the church, which Hermas is directed to deliver.

In a third vision, an angelic young man discloses the identity of the heavenly woman to Hermas, who at first mistakes her for the Sybil: “‘Then who is she?’ I asked. ‘The church,’ he said. ‘Then why is she elderly?’ ‘Because,’ he said, ‘she was created before everything. That is why she is elderly, and for her the world was established.’”60

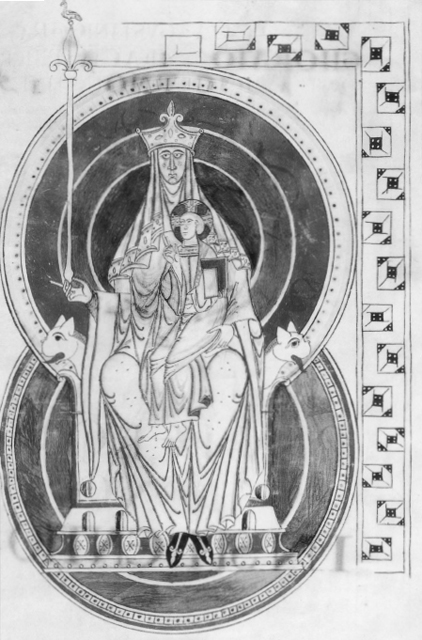

FIGURE 27

Mary as Wisdom, on the lion throne, c. 1150. Eynsham Abbey, Oxfordshire. (From Kyra Belán, Madonna: From Medieval to Modern [New York, NY: Parkstone Press, 2001])

Although the church is preexistent and heavenly, she is also an imperfect community being built up through history. She is portrayed as a tower being built by angels, who are selecting the “stones” (believers) that have true faith and those with true repentance and discarding those who have fallen away and failed to repent. Lady Church then reveals to Hermas seven daughters. The first is Faith, and the other six—Restraint, Simplicity, Knowledge, Innocence, Reverence, and Love—are each in turn the daughter of the previous child. Through them, the tower church is being built. When Hermas asks Lady Church how soon the building of the tower will be completed, she fiercely rebukes him, for when the tower is completed, this will be the end of history.61 This time is soon, but it is not yet come and cannot be known at this time.

In language drawn from the Wisdom treatises, Lady Church then addresses Christians as “children,” who were raised to be “justified and sanctified from all evil” but who have fallen into quarrelsome and sensual habits. She singles out the leaders of the church, declaring that they cannot discipline others if they do not discipline themselves. Lady Church gives them a short time to rectify their ways before she prepares a final accounting to God.62

In a final vision of Lady Church, the meaning of her various “ages” is revealed. When first seen, she was old and seated in a chair; in successive visions, she becomes younger and more beautiful. This growing youth represents her ongoing rejuvenation through the coming of Christ and new converts reborn in Christ. Her youth also anticipates her final transformation in the renovation of the world.63 Thus, for Hermas, Lady Church is both a heavenly reality, the original purpose of Creation and its eschatological fulfillment, and also an earthly reality being built up day by day as a community of faith. This process is drawing to a close but has not yet reached its final point; Christians, then, still have a chance to reform their lives and be incorporated into its secure edifice.

Although the idea that the church is the spouse of Christ, impregnated through his passion to bear children in baptism, implies that the church is our mother, this image was rarely used in the second century.64 It became central in the middle of the third century in the theology of the African bishop Cyprian, who used it to distinguish the true children of God from schismatics who had separated from the one faithful spouse of Christ, the true apostolic church.

Although the church “spreads her branches in generous growth over the whole earth,” yet there is one source of this fecundity, “one mother who is prolific in her offspring, generation after generation. Of her womb we are born, of her milk we are fed, of her Spirit our souls draw their life breath.” Since this true mother is the undefiled spouse of Christ, she “is faithful to only one couch.” Anyone who breaks with this one apostolic church and joins a sectarian church thus enters an adulterous household. Baptism in such churches is null, lacking true power of regeneration. Such a person has no true relation to God. In a phrase that would be reiterated in his writings, Cyprian insists, “You cannot have God for your father if you have not the church as your mother.”65

This image of the church as virginal mother is more fully developed in Augustine, who applies it directly to his own spiritual journey as well as to all Christians reborn in the waters of baptism. Although Monica is for Augustine in some sense a model for Mother Church, who elects him from her womb, pursues him, and will not tire until she sees him safely incorporated into the one true Catholic Church, the motherhood of the church also supersedes human motherhood. The birth we receive from our mothers is one from which we die, in the sin transmitted by sexual reproduction. We receive true birth, the birth from which we will not die but have immortal life, only in the womb of Mother Church, in the waters of baptism. The milk of the catechumenate gives us true nourishment, while only mortal life flows from the breasts of our mothers. Thus, for Augustine, the motherhood of the church is contrasted with the inferior birthgiving and nurturance of actual mothers,66 as true life to spiritual death, purity to impurity.

MARY IN THE NEW TESTAMENT AND PATRISTIC THEOLOGY

Much of this feminine imagery of the church as Wisdom, bride, and mother would be absorbed into Mariology by the later church fathers and during the Middle Ages. Already in the late fourth century, Ambrose and Augustine had identified Mary as the “type” of the church.67 Standing with her cloak sheltering the Christian people, the Madonna of the Misericordia is the protecting Mother Church (fig. 28). Yet, in the New Testament, Mary is a minor figure. She is never mentioned by name outside the Gospels and the Book of Acts. Paul speaks only once of Jesus's mother and then simply to assert the human status of Jesus: “when the time had fully come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law to redeem those who were under the law” (Gal. 4:4).

The few references to Jesus's mother in the synoptic gospels, aside from the infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke, seem to reflect a tradition that positions Mary and Jesus's brothers as unbelievers, linked to a hostile hometown community of Nazareth and not to the church. Mark describes this local community as seeking to seize Jesus, believing him to be mad. Jesus's mother and brothers then come and, standing outside, ask to speak to him. But Jesus repudiates them, identifying his followers—and not his family—as his “brother, sister and mother” (Mark 3:21, 31–35). Matthew 12:45–50 and Luke 8:19–21 repeat the same story with variations.

FIGURE 28

Madonna of the Misericordia, by Piero della Francesca, 1445–62. Centerpiece of polyptych. (Pinacoteca Communale, Sansepolcro; photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY)

The two references to Jesus's mother in the Gospel of John also seem to locate her as part of the old Israel, although a part that is open to the new. In John 2, she intervenes at the marriage feast at Cana to ask Jesus to perform a miracle to supply wine. Jesus addresses her harshly: “Woman, what have you to do with me? My hour is not yet come.” The stone water jars that his mother asks him to use to produce the wine are then identified as part of the Jewish rites of purification. Jesus is the new wine that will supersede these old, inefficacious rites. Mary, Jesus's mother, reappears at the foot of the cross, along with several women disciples. Jesus entrusts her to the care of the “disciple” (John). Here, she is that part of the old Israel that is transferred to the care of the new (John 19:25–27).68

Significantly, none of the synoptic gospels place Mary either at the cross or at the empty tomb as witness to the resurrection. In these instances, the women disciples of Jesus, led by Mary Magdalene, are the chief actors and representatives of the believing remnant of the church. Mary Magdalene is also the first witness to the resurrection in John; Jesus's mother is not mentioned. These absences seem to reflect an early view that Mary was not part of the community of believers in Jesus's life-time. However, in Acts, the believing community in Jerusalem, which awaits the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, includes the eleven male disciples, with the “women” (disciples) and “Mary the mother of Jesus and with his brothers”(Acts 1:13–14). Although Mary is not mentioned thereafter, Jesus's brother James plays a key role as a leader of Jewish Christianity in Jerusalem (Acts 15:13; Gal. 2:9).

The tradition of Mary's virginal conception of Jesus appears in the infancy narratives added to the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.69 Yet Mary plays very different roles in these two narratives. In Matthew, Joseph is the central figure. He at first takes Mary's pregnancy prior to their marriage as evidence of her wrongdoing and resolves to divorce her, until he is told by an angel in a dream that the child was conceived by the Holy Spirit. He then accepts her as his wife. Two further angelic visits in dreams tell Joseph to take Mary and Jesus to Egypt and then bring them back again when Herod has died. Mary remains a passive figure in this drama (Matt. 1:18–2:21).

In Luke's infancy narrative, by contrast, Mary is an active agent in the miraculous conception. She is the one who receives the angelic visit announcing God's plan and accepts it: “Behold I am the handmaiden of the Lord. Let it be done to me according to thy word” (Luke 1:38). This scene would become a favorite in art (fig. 29). In a visit to her cousin Elizabeth, Mary greets her with a song that identifies herself as the prototype of the messianic community through whom the wrongs of history will be righted. Mary stays with Elizabeth three months and never consults Joseph through any of these events. She is the central player in Jesus's birth, although Joseph is at her side. Clearly, it is the Mary of Luke's infancy narrative who is the font of Christian Mariology. From these modest seeds, a mighty thicket would grow over the following centuries.

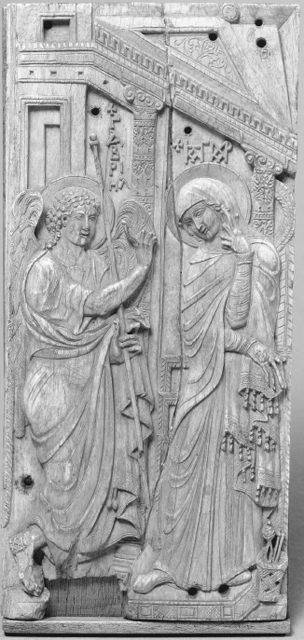

FIGURE 29

The Annunciation, c. 700. Ivory relief. The wool blanket at the virgin's feet alludes to the legend of her upbringing in the temple of Jerusalem, where she spun and made robes for the priests. (Castello Sforzesco, Milan; photo: Scala/Art Resource, NY)

The second century saw the first major elaboration of Mary's redemptive role, building on Luke's infancy narrative. Drawing on Paul's theme of Christ as the new Adam (Rom. 5:12–21), several second-century church fathers created a parallel role for Mary as the new Eve.70 This theme was enunciated in the middle of this century by Justin Martyr. Here, the disobedience of the virgin Eve at the behest of the serpent, through which death comes, is paralleled and reversed by the obedience of the virgin Mary to the good tidings of the angel Gabriel. Her obedience brings about the birth of the Son of God, through whom death and the serpent are destroyed.71

A generation later, Irenaeus elaborated this parallel. The virgin Eve's disobedience brings death for herself and for the whole human race, whereas the obedience of the virgin Mary is the cause of salvation for herself and for the whole human race.72 Irenaeus returned to this theme in his fifth book: “And if the former did disobey God, yet the latter was persuaded to be obedient to God, in order that the Virgin Mary might become the patroness of the virgin Eve. And thus as the human race fell into bondage by means of a virgin, so it is rescued by the virgin; virginal disobedience having been balanced in the opposite scale by virginal obedience.”73

Irenaeus assumes that Eve and Mary, like Adam and Christ, are corporate personalities. Eve's disobedience and Mary's obedience affect all of humanity, the one bringing death to all and the other making eternal life available to all. Mary is thus assigned an essential role in the history of salvation. Although her son is the one who redeems us, he would not have existed without his mother's “fiat” to the angel. Her redemptive obedience precedes and makes possible his redemptive work.

The notion of the virginal conception of Jesus, developed in the infancy narratives of the gospels, signified an understanding of Jesus as God's elect from his mother's womb—that is, his coming was through divine and not human agency. Yet Matthew's tracing of Jesus's genealogy from Abraham and David to Joseph was constructed by a writer who assumed Joseph's paternity (1:2–16). Matthew's infancy narrative, although claiming a virginal conception for Jesus, takes for granted that Mary and Joseph had sexual relations after Jesus's birth: “He took his wife, but knew her not until she had borne a son, and he called his name Jesus” (1:24–5). Mark speaks of Jesus as “the carpenter, the son of Mary, and brother of James, and Joses, and Judas and Simon, and are not his sisters with us?”(Mark 6:3).74 Joseph is absent in this account (although he is inserted in Matthew 13:56, where Jesus is called “the carpenter's son”). These references seem to assume that the brothers and sisters of Jesus are Mary's children.

But the developing asceticism of early Christianity soon made these assumptions unacceptable. For ascetics, virginity is the purest state of life, while sexual marriage is less pure. Those who would anticipate the kingdom of heaven, where there is no marrying, give up marriage and sexual relations (Luke 20:35). This ascetic interest shifted the focus from the virginal conception of Jesus, as an expression of his divine election, to Mary's virginity as an expression of her purity. As the epitome of the eschatological ethic of virginity, she cannot be imagined to have “fallen back” into the lower state of marriage and sexual reproduction. Hence, her subsequent sexual relations with Joseph and her maternity of Jesus's brothers and sisters must be denied.

An early expression of this view is found in the Proevangelium of James, an apocryphal gospel from the middle of the second century.75 This book purports to have been written by Jesus's brother James. It begins with the story of Mary's parents, Joachim and Anna, a rich and pious couple who are childless. After prayer and supplications, both receive angelic revelations that they will have a child. They vow to dedicate the coming child to service in the temple. When Mary is born, she quickly shows a precocious piety and is duly dedicated as a perpetual virgin. When she is twelve, the temple priests decide that Mary must be put under the guardianship of a widower, lest her menses pollute the temple. They announce a contest of widowers. Joseph, an old man with grown children, is selected through a divine sign (a dove that flies out of his staff).

Mingling the infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke, the Proevangelium then describes how Mary receives the angelic visitation and becomes pregnant. She stays three months with her cousin Elizabeth while Joseph is away on a building contract. He returns when she is six months pregnant. He assumes that she has sinned but is informed otherwise by an angel. Both Joseph and Mary are accused of sin by the priests, but they are vindicated through an ordeal. The Proevangelium then goes on to recount the miraculous birth of Jesus, which does not violate Mary's virginity.

As Mary and Joseph travel to Bethlehem, Mary's time for delivery comes. Joseph leaves her in a cave and goes to fetch a midwife. The midwife returns with him and is an eyewitness to the miraculous birth, in which the cave is flooded with light and the infant, like a beam of light, passes through Mary's hymen without breaking it. The midwife then runs and encounters a second midwife, Salome, to whom she tells the story of the miraculous birth. Salome plays the role of doubting Thomas, insisting that she will not believe that a virgin has brought forth unless she can test this with her own finger. She then enters the cave and demands that Mary show her genitals. Probing them with her finger, she verifies that Mary's hymen is indeed unbroken, but Salome's hand is immediately withered by fire. Only when she repents and is entrusted to embrace the child herself is her hand healed.76

This pious tale would deeply shape subsequent Christian imagination of Mary's infancy and the virgin birth, but it was not quickly accepted by leading church fathers. Tertullian expressed the established view of his time, which held that Mary, although a virgin at the conception of Jesus, subsequently was the faithful wife of Joseph. Tertullian took her to be a representative of the blessedness of both states of life, virginity and faithful monogamy.77 He did not discuss the issue of whether the brothers and sisters of Jesus were the children of Mary, but the view that they were half-siblings, children of an earlier marriage of Joseph, was gaining currency and was embraced by the Alexandrian father Origen.78

By the late fourth century, Tertullian's view had become unacceptable. About 382 CE, Helvidius, a Latin cleric, defended the equal status of virginity and marriage by pointing to Mary as an exemplar of both states. Although she had been a virgin at Jesus's birth, he pointed out, she subsequently had sexual relations with Joseph and bore the children referred to in the gospels as brothers and sisters of Jesus. Jerome responded with great outrage at the thought that Mary, having once been a pure virgin, could have regressed to the inferior status of wife. In a convoluted exegesis, he insisted that the brothers and sisters of Jesus were actually cousins, children of a sister of Mary (also called Mary), and that both she and Joseph were perpetual virgins.79

A monk, Jovinian, then challenged Jerome, labeling him a Manichean. Jovinian declared that both marriage and virginity were equally blessed and attacked the view that virgins would have a higher place in heaven than the faithfully married. This attack gave Jerome the opportunity to defend his insistence that virginity was indeed a higher state of life than marriage. Although marriage was still allowed in Christian times, he argued, a vowed virgin who “fell” into the inferior state of marriage was to be condemned.80 This view was endorsed by Ambrose and Augustine and became the accepted orthodoxy, while Jovinian was condemned at several church councils.81 Thus, the doctrine of Mary's perpetual virginity became enshrined in church teaching as an expression of the superiority of virginity to marriage.

The next major controversy in relation to Mary arose in the Eastern church over the increasing use of the title Mother of God (Theotokos) for her. At its heart, this is a Christological rather than a Mariological issue. It has to do with how one defines the two natures of Christ, divine and human. Are they to be kept clearly separate, so that Mary can be spoken of only as mother of Jesus's humanity? Or are the two natures so commingled—that is, the human one she bore is also God—that she can be spoken of as Godbearer?82

Antiochene theologians, such as Theodore of Mopsuestia and his disciple Nestorius, bishop of Constantinople in 428 CE, favored a clear separation of the two natures, seeing them as united in Christ by Jesus's act of will in obeying God rather than by an ontological union. In contrast, the theologians of the Alexandrian church argued that the incarnation of Christ brought together the two natures into one divine-human union, ending any separation. This view of Christ was foundational to their concept of salvation as a divinization, in which humans are transformed through Christ into a share in his divine-human nature. In this view, Mary can appropriately be called Theotokos.

After violent clashes at various church councils, the matter was officially resolved in the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE. Aided by an intervention from the Roman Pope Leo, this council defined the two natures of Christ as both distinct and whole each in themselves and yet united in such a way that it is possible to speak of Mary as Godbearer.83 This is not because Mary is literally God's mother, but because, in bearing Christ's humanity, she also bore one who was God.

These careful distinctions satisfied Catholic orthodoxy, but not Alexandrian Monophysites or Antiochene Nestorians, both of whom refused to accept the formula of Chalcedon and split into separate churches. But such distinctions hardly account for the passion with which Mary's title of Theotokos was defended by its partisans. When this title was vindicated at the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE, the people of Ephesus danced in the streets.84 The people of this city, formerly devoted to Artemis, clearly saw Mary as Mother of God in a fuller sense. She was a divine mother who bore within herself the mystery of the universe and could be venerated as a continuation of that Magna Mater and mother of the gods long worshipped by Mediterranean people as a guarantor of good fortune. The orthodox icon of Mary Panagia gives us one powerful image of the Theotokos (fig. 30).

Something of this veneration of Mary as Godbearer is captured in a section of the apocryphal Gospel of Bartholomew, a Coptic collection of the fifth century. In this text, the resurrected Christ teaches the apostles the mysteries of redemption and then vanishes. Mary is with the apostles, and they decide to ask her “how she conceived the incomprehensible or how she carried him who cannot be carried or how she bore so much greatness.” She warns them that she cannot describe this mystery: “For if I begin to tell you, fire will come out of my mouth and consume the whole earth.”85

But the apostles continue to entreat her to describe the conception of God. She then calls them to pray. She spreads her hands to the heavens and prays to God as the creator of the cosmos, who ordered the vault of the heavens and separated darkness from light: “The seven heavens could hardly contain thee, but thou wast pleased to be contained in me, without causing me pain, thou who art the perfect Word of the Father through whom everything was created.” Mary then calls the apostles to be seated around her, each holding a part of her body, lest her limbs might be loosened when she describes the mystery of her conception of the Creator. She begins to tell the story of the appearance of the angel who announced the impending conception. “As she was saying this, fire came from her mouth and the world was on the point of being burned up. Then came Jesus quickly and said to Mary, say no more or today my whole creation will come to an end.”86 Clearly, in the imagination of this writer, the mystery that was contained in Mary's womb was not simply a humble human who was also God but was in fact the Almighty, the Creator of the whole cosmos. The thirteenth-century image of the Vierge ouvrante is a striking expression of this view of Mary as containing the entire Trinity and cosmos (fig. 31).

FIGURE 30

The Virgin of the Great Panagia (also known as the Virgin Orant of Jaroslav), c. 1224. (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow; photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY)

FIGURE 31

Vierge ouvrante, c. 1400. (Musée du Moyen Age [Cluny], Paris; photo: Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY)

Although the title Theotokos allowed Christians to venerate Mary as one who had contained and borne God, controversy remained about the status of her own conception and her death. These questions were closely related in the thought of the time. Humans were believed to have been originally created with sinless and undying bodies. Disobedience caused them to fall into mortal bodies, which then necessitated sexual reproduction. But at the resurrection, believers were to be restored to their original spiritual and immortal bodies. If Mary had been conceived sexually, presumably she shared in this same sinful mortality. She too, then, would have died, and her body would have fallen into corruption, like all other humans. Her soul would thus have to await the future resurrection of the dead, when her risen body would be joined to her soul.

But other Christians were convinced that Mary must have been purified from any actual sin and thus that her body would not have been corrupted. Two different apocryphal texts of the late fifth century seek to answer these questions of Mary's death. In one, Pseudo-John “Concerning the Falling Asleep of Mary,” Mary dies surrounded by the apostles and is laid in a tomb. After three days, her body is transported to paradise, where she joins other saints and awaits the resurrection of the dead.87 But in Pseudo-Melito “On the Passing of Mary,” Mary's dead body shines with heavenly light, revealing its immunity to corruption. The apostles then carry her to her tomb. Jesus appears and asks the apostles what they think should happen to Mary. They express the view that she should share immediately in Christ's resurrection and not suffer the corruption of death: “Thou having vanquished death reigns in glory, so raising up the body of thy mother, thus should take her with thee into heaven” (fig 32). Jesus agrees and orders the archangel Michael to bring Mary's soul and to roll back the stone from the door of the tomb. Jesus summons Mary to arise: “Arise my beloved and my nearest, Thou who hast not put on corruption with man, suffer not the destruction of the body in the sepulchre.” Mary arises and is carried by angels bodily into heaven, along with Jesus.88 The first view does not give Mary a greater status than other great saints, who also await in some celestial realm the future joining of soul and body in the resurrection. The second view sees Mary as already sharing with Christ in the bodily resurrection and locates her with him in heaven.

It was assumed that Mary had never been tainted by actual sin and thus was preserved from mortal corruption. But Christian tradition did not see her own conception as virginal, even though some versions of the Proevangelium of James suggest that this was the case (by having Anna already pregnant through an angelic vision when her husband, Joachim, returns from his retreat to the desert to pray for a child).89 This issue became more controversial in the Western church, with the victory of the Augustinian view that original sin, from which we all die, is transmitted by the sexual act of our parents. Although Augustine believed that Mary had been cleansed in the womb from the effects of original sin and hence never fell into actual sin, he does not exempt her from an initial transmission of original sin, which was the necessary result of her sexual generation.90 Only Christ was conceived virginally and hence was exempt from original sin. Mary, then, shares with us the general human condition of children of the fall.

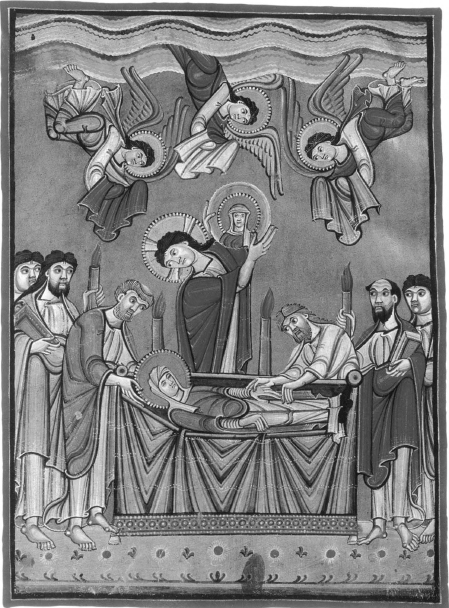

FIGURE 32

The day of Mary's death and resurrection is August 15, known as the Assumption. The page shown here is from the feast-day gospel with tablets of the canon from the school of Reichenau, c. 1030. (From Caroline H. Ebertshauser et al., Mary: Art, Culture, and Religion through the Ages [New York: Crossroads Publishing, 1997])

This problem of Mary's sinlessness would continue to be debated, even among medieval theologians. It was eventually resolved by the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, which defined Mary as cleansed from the effects of original sin in the very act of being conceived and thus free from sin from the moment of conception.

Although the details of Marian theology, as well as practices of devotion to Mary, would greatly expand in the Latin Middle Ages, the main outlines of Mariology were largely in place by the end of the fifth century. A sinless virginal mother, the epitome of Christian virtue, had been installed in heaven side by side with Christ, there to be available as benefactress who would hear our prayers and come to our assistance in distress. Despite the quibbles of theologians about the distinctions between hyperdulia (high veneration) owed to Mary and latria (worship) owed to God alone,91 Christians now had a divine mother in heaven to whom they could turn when the male God and his Son appeared impervious to their needs.