SIX • Feminine Symbols in Medieval Religious Literature

MARIOLOGY

The Middle Ages would see a great flowering of devotion to Mary. Her feast days proliferated, hundreds of churches were dedicated to her, and the Mary altar became a standard part of every church. Relics of her hair, milk, clothing, and house multiplied in numerous shrines. Private devotions, such as the rosary, were created so that worshippers could pray to her daily. Contemplative men and women saw her in visions and dedicated their lives to her service. Hymns, paintings, and sculpture celebrated all aspects of her life, from her own conception and the birth of Jesus to her Assumption and crowning as queen of heaven. Theologians debated the expansion of her titles and special privileges.1

Eastern and Western Christians agreed that, because of her virginal purity, her body at death did not suffer corruption. But the question of whether this body was preserved in some paradise to be united with her soul at the general resurrection or whether she had been resurrected and assumed bodily into heaven immediately after her death remained open. In the eighth century, shocked by the expansion of Islam and its conquest of the holy city of Jerusalem, several Greek church fathers—Germanus (d. 732), patriarch of Constantinople; Andrew of Crete (d. 740) and John Damascene (d. c. 749), both monks in Jerusalem—appealed to the apocryphal stories of her Dormition (“falling asleep” in death) in Jerusalem as official church teaching. John Damascene argued for the Assumption through analogy to Christ's Ascension: “Rather, just as the holy and incorrupt body that had been born of her, the body that was united hypostatically to God the Word, rose from the tomb on the third day, so she too should be snatched from the grave and the Mother restored to her Son; and, as He has descended to her, so she should be carried up... to heaven.”2

In 600 CE, the emperor Maurice ordered that the Dormition of Mary should be celebrated on the fifteenth of August.3 This date was accepted in the West as the feast of the Assumption. In the mid-ninth century, Pope Nicolas I put this feast on a par with Christmas and Easter.4 The German visionary Elizabeth of Schönau (d. 1164) saw Mary rising bodily into the heavens and crowned queen of heaven.5 The circulation of these visions, which were transcribed by Elizabeth's brother Ekbert, the abbot of Schönau, further disposed the Western church to believe in Mary's bodily assumption, although the doctrine was not officially declared until 1950, by Pope Pius XII. By that time, images of Mary bodily ascending into heaven had become a favorite theme for church paintings, familiar to all Catholics, and hence appeared to support an established “fact” (fig. 33).

The corollary belief, suggested by Augustine, that Mary had been sanctified in her mother's womb and therefore preserved from all actual sin from birth was also generally accepted in the West. But the hint found in the Proevangelium of James that she had been conceived without her parents actually having sexual intercourse was not acceptable. Only Christ had the special privilege of being conceived virginally and therefore being untainted by original sin. The view that Mary had been conceived sexually—and thus that original sin had been transmitted to her—was intrinsic to the affirmation that she was a part of fallen humanity, saved like all other humans through her son.

Sanctification in the womb could not be pushed back to coincide with her conception, which would have exempted her from the common human condition of original sin and therefore from the need for salvation by Christ. Defense of this principle caused the major theologians of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries—Bernard of Clairvaux, Thomas Aquinas, and Bonaventure—to reject the concept of Mary's Immaculate Conception. Some interval between her conception in original sin and her sanctification, when Christ's grace was applied to her to remedy the effects of sin, must be maintained, they argued.

In 1140, Bernard of Clairvaux penned a horrified letter of protest to certain canons of Lyon who had instituted a festival of the Immaculate Conception. Although Bernard affirmed that Mary had been sanctified in the womb, he declared that her conception had nevertheless been sexual and that she shared the human condition of original sin. Her sanctification itself presumed a prior sin in need of remedy: “If then she could not be sanctified before her conception, because she did not exist, neither in her conception itself, by reason of the sin that was there, it remains that we believe that already conceived and existing in her mother's womb she received sanctification which, taking away the sin, made her birth holy but not her conception.”6

FIGURE 33

The Assumption of Mary, by Titian, sixteenth century. Oil on canvas. (S. Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice; photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY)

For Thomas Aquinas, the concept of the Immaculate Conception defied his understanding of human gestation. In his view, since the soul is the form of the body, ensoulment must take place some months after conception, when the body of the fetus assumes its human form. Thus, sanctification in the womb can take place only after ensoulment, not at conception. This position was necessary for two reasons: first, to affirm that Mary shared the human condition of sin and hence was dependent on Christ for her salvation; and, second, because there cannot be a purification of a human before she is fully human—that is, before soul and body are joined.7

This topic was hotly debated in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with the Franciscans pushing for the Immaculate Conception and the Dominicans following Aquinas's position, which acknowledged an interval in which Mary existed in original sin. The fourteenth-century theologian Duns Scotus attempted a bold resolution of the conflict. Arguing that it was a higher honor to be preserved from damage than to remedy it after it has taken place, Scotus suggested a backdating of Mary's sanctification to the moment of her conception. Although her conception was sexual and thus carried with it in theory the penalty of original sin, by a special grace Christ prevented original sin from actually being transmitted along with the seed by which Mary was conceived. Thus, Mary was still redeemed by Christ's grace, without having ever suffered even a moment of existence in original sin.8 This theory also eliminated the interval between conception and ensoulment, which was part of the generally accepted medieval view of gestation, derived from Aristotle. As a result, Catholic thought came to argue that the soul is transmitted to the zygote from the moment of conception, not at a later stage of fetal formation. Although this view became normative only in the nineteenth century, current Catholic opposition to abortion from the first moment of conception assumes this view of gestation.9

Scotus's solution to the problem of the Immaculate Conception did not immediately win the day. The Council of Basel declared it a doctrine in 1439, but the council's decision was not taken as valid by the Curia. In 1426, Franciscan Pope Sixtus IV granted special indulgences to those celebrating the feast of the Immaculate Conception. Nevertheless, debate continued with such acrimony that further discussion was forbidden in 1482 on pain of excommunication. This command did not silence the argument and had to be repeated in 1483 and 1503.10

The Council of Trent did not rule definitely on the issue, even though the major Counter-Reformation order, the Jesuits, enthusiastically backed the notion of the Immaculate Conception. Its declaration as a doctrine in 1854 by the anti-modern Pope Pius IX appeared to be a deliberate defiance of modern enlightenment and a test case for the pope's subsequent declaration of papal infallibility in 1870.11 As early as the sixteenth century, artistic representations of Mary as the Immaculate Conception had become popular, using elements of Revelation 12 to picture her as a virginal girl standing on the moon or on clouds in a heavenly space (fig. 34).

FIGURE 34

The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, c. 1638. Spain. (Courtesy National Gallery of Ireland)

These two doctrines, Mary's preservation from original sin and her bodily assumption into heaven, which were still under some debate at the end of the Middle Ages, nevertheless drew on what was already an established stream of popular piety, always ahead of official doctrine. Popular devotion had long visualized Mary not only as bodily assumed into heaven but also as crowned by Christ and reigning on his right hand as queen of heaven (fig. 35). She was understood to be uniquely influential with Christ. From the twelfth century, the sermons of St. Bernard described Jesus and Mary as dividing the kingdom of heaven, with Jesus representing strict justice, while she moderated his judgments on sinners through her mercy.12 This gendered dualism of justice and mercy made Mary the hope of sinners, the mediatrix to Christ, who was the mediator with the Father.

Popular piety spun endless stories of feckless sinners, deserving of hell or at least a long time in purgatory, who, through their devotion to Mary, were rescued at the last minute, allowed to repent, and thus saved. In one popular story, a wayward girl was decapitated and her head thrown in a well. Because of the girl's devotion to the rosary, Mary intervened to keep the head alive. The head was brought up at the command of St. Dominic and allowed to confess and receive communion, sparing the girl's soul.13 Through such tales, Christians' fear of strict juridical justice was assuaged. They were assured that they had a mother in heaven and that, like all mothers, she had a soft heart for her children. If they only continued to love her, she would intercede for them with her son, who could refuse his mother nothing.

This splitting of the heavenly realm between justice and mercy positioned Mary as the representative of the purely human, in a way that identified the feminine with the human, the masculine with the divine. Jesus too is human, but as his humanity is hypostatically united with his Godhead, he belongs more to the God side of the human-divine dichotomy. Mary as feminine, and purely human, is more in touch with human feelings and failings.

Mary's sinlessness, even without a clear doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, allowed medieval piety to see her as representing the innocent humanity that had existed before the fall. Adam and Eve, though originally good, had the freedom and capacity to sin; Mary alone preserved our original goodness, although more perfectly, since she was not able to sin. Representing that goodness, she assured Christians that this good nature was still available to them, despite its disfigurement in sin.

The Assumption of Mary ratified her uncorrupted goodness and so held out to believers the hope that they too could look for such an eventual unification of redeemed soul and uncorrupted body in a heavenly world to come. Mary thus took over theological functions that once had been served by Jesus's humanity, resurrection, and ascension. As the developing understanding of his God-manhood came to make him too removed from the human condition, Mary became the guarantor of these human hopes, as one who was “purely” human, in both senses of the word “pure.”14

FIGURE 35

The Coronation of Mary, by Jacopo Torriti, 1292–95. (S. Maria Maggiore, Rome; photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY)

Some medieval speculation pushed Mary even beyond this status as representative of our original good nature. Gabriel Biel, fifteenth-century theologian and member of the Brethren of the Common Life, adhered to a belief in the preexistence of Mary's soul. As an advocate of the Immaculate Conception, Biel located this not only in her purification at the moment of conception but in her creation in sanctifying grace before Creation itself. Here, Mary takes on the lineaments of divine Wisdom, created at the beginning, sharing with God in the creation of the world.15 But this perfection of her unfallen soul, breathed into her body at her conception, does not take her beyond the creaturely into being part of the Trinity. Rather, it reflects a view of the soul itself as God's perfect icon, for which the world was created. Mary's soul exemplifies the original and true nature of the soul.

Mary, then, is the pure virgin at her conception and at the birth of Jesus as well as the exalted queen of heaven. But she is also the sorrowful mother. She understands and is with us in our suffering. More fundamentally, she shared fully in her son's suffering, having foreknowledge of his crucifixion from his birth. She stood at the cross, joined with him in his pain, and also offered his suffering to God for the redemption of the world. These ideas suggest that Mary is co-redemptrix, although they stop short of the obvious conclusion that she represents the priest at the cross.16

Only through Mary's fiat was Christ born, and only with her consent was he offered up for our sins. This view suggests the importance of human consent to God's grace. God saves us only through our cooperation with his grace, not against our will. This theme also identifies Mary with the theology of the church. She is the exemplar of Mother Church, who, through the priest, offers Christ to the Father at Mass and who distributes Christ's saving grace to the fallen world. As in Cyprian of Carthage's ecclesiology of Mother Church, no grace comes to us save through the (true) Mother Church. This theme of co-redemptrix has yet to be declared a doctrine of the Catholic Church, although Pope John Paul II has indicated his wish to do so.17

HILDEGARD OF BINGEN: A PANOPLY OF FEMININE SYMBOLISM

Feminine symbolism is also central to the work of several key medieval mystical writers. One in particular, Hildegard of Bingen, was the abbess of the Benedictine community in Rupertsberg, near the modern German town of Bingen. Hildegard was one of the most extraordinary and prolific writers of the twelfth century (1098–1179). She produced three major visionary writings that combine cosmology, theology, and ethics: Scivias (Know the Ways), written over ten years, from her early forties to early fifties; The Book of the Rewards of Life (Liber Vitae Meritorum), a compendium of virtues and vices, rewards and punishments, written in her early sixties; and The Book of Divine Works (De Operatione Dei), a reworking of her theology in a cosmological context, written in her late sixties and seventies.18 In addition, Hildegard wrote two treatises on natural science and medicine (Physica and Causae et Curae), two saints' lives, a compendium of answers to theological and scriptural questions, an explanation of the Benedictine rule, a morality play, a cycle of songs set to music (Symphonia Armonie Celestium Revelationem), various other occasional writings, and hundred of letters to people of all social strata.19

Hildegard was not a contemplative mystic in the sense of one charting her soul's personal journey to God. Her visions take the form of vast images covering the whole sweep of cosmological relations between God, the cosmos, and humanity. They encompass salvation history from creation, the fall of Lucifer and the primal parents, the preparation for Christ in the history of Israel, the birth of Christ from Mary's virginal womb, the struggle to build the church, the anticipation of the coming Anti-Christ, and the consummation of world history. These visions appear in vivid pictorial representations, which Hildegard both explicated in words and had painted in symbolic colors, probably by women of her monastery.20

One of the most striking aspects of Hildegard's visions of cosmology and salvation history is the panoply of interconnected feminine symbols by which she depicts this story. Hildegard synthesized in a unified theological system of relationships an entire range of feminine symbols from the scriptures and Christian tradition, including Wisdom, Eve, Mary, and the church.

In Hildegard's work, the foundational feminine figure present with God from the beginning, the link between God and creation and the means of God's creation of the world, is Wisdom (Sapientia), also called Love (Caritas). The roots of this image lie in the Wisdom literature of Hebrew scripture, which continued to be read as an integral part of the Bible of the medieval church. Although the New Testament and the early church identified (and masculinized) Wisdom as Christ, Hildegard reclaimed and developed this figure in her feminine personification. Hildegard followed a Platonic, exemplarist cosmology that saw all things that are to be created existing originally in the mind of God. Wisdom is present in and as God from all eternity, as the mind of God and the collective preexistence of all that is to be created.21

Wisdom is the means by which God brings all preexistent ideas to be manifest in material form. In this role, Wisdom can be spoken of as the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and end of all things, who orders the whole creation. “She has invoked no one's help and needs no help, because she is the First and the Last... she who is the First has arranged the order of all things. Out of her own being and by herself she has formed all things in love and tenderness.... For she oversaw completely and fully the beginning and end of her deeds because she formed everything completely, just as everything is under her guidance.” Hildegard speaks of the whole creation as “Wisdom's garment.”22

Wisdom is the energy—or, in Hildegard's favorite metaphor, the “greening power” (veriditas)—that gives life to all things, subsisting in God as the source of life. All creatures are “sparks from the radiation of God's brilliance.”23 In a hymn to Wisdom, O Virtus Sapientie, Hildegard exclaims, “Oh energy of Wisdom, you circle circling, encompassing all things in one path possessed of life. Three wings you have, one of them soars on high, the second exudes from the earth and the third flies everywhere. Praise to you, as befits you, O Wisdom.”24 The creation is not so much an object outside of God as encompassed by God. Like a timeless wheel, “the Holy Godhead enclose[s] everything within itself.”25

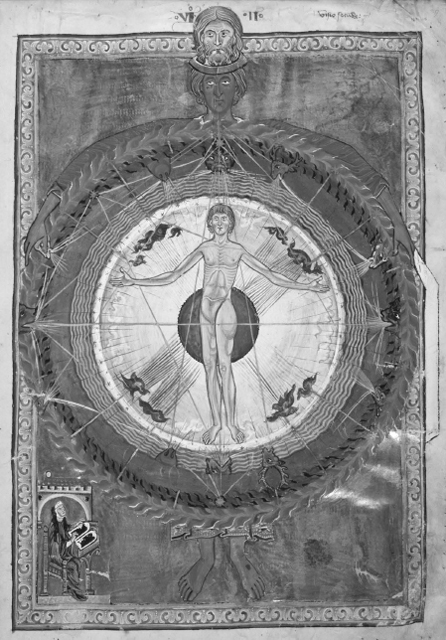

This encompassing of the creation by God is imaged as a cosmic circle with the outer rings of the stars, planets, and elements. The earth lies in the center, in which the human being stands as microcosm to macrocosm. The whole cosmic circle is encompassed by the feminine figure of Wisdom, or Love, who embraces it as her body.26 Wisdom is thus the anima mundi, the world soul whose life-giving immanence causes the whole cosmos to live (fig. 36). Wisdom is also materia, the matter that founds all bodily existence.27 Wisdom interconnects the divine and the creaturely. She is both the creator's self-manifestation and the creature's loving, exultant response to its creator, the mutual indwelling of God and creatures.

The relation of God and Wisdom (or Love) is also described erotically. Wisdom is God's bride, “united with him in most tender embrace in a dance of blazing love.”28 Wisdom is a “most loving friend full of love” for God. “She will remain with God since she is always with him and will always remain with him.”29 At the same time, she is providence who rules the world. “Wisdom is the eye of God which foresees and contemplates all things.” Like a good wife, she performs the heavenly works through which humans clothe themselves. Like a mother, she teaches her children how to work. Encompassing both the physical and the ethical/spiritual aspects of this “work,” Wisdom clothes and teaches her offspring to clothe themselves in virtues, like a wife who weaves wool and flax to cover the nakedness of her family.30

Wisdom speaks through human sciences to understand the natural world. She is also the Wisdom of the philosophers. But, more, she is the source of the revelatory and redeeming knowledge that brings the fallen world back to God. Like streams of living water, she speaks through the prophets in Israel's history. She brings to fruition the central act of God's redeeming work, in the incarnation of Christ in Mary's virginal womb. She speaks through the evangelists. The theological knowledge of the church springs from her. Like Wisdom in Proverbs, she stands on the seven-pillared “house of Wisdom,” understood to be the church.31 Through Wisdom, salvation history is brought to its culmination, and creation attains its final communion with God.

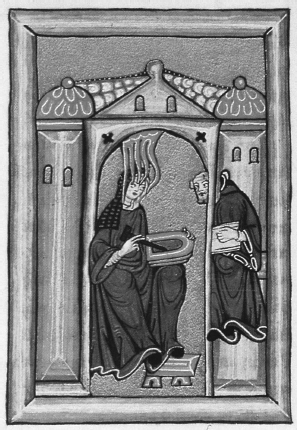

Last but not least, Wisdom speaks through Hildegard herself, both in her knowledge of natural sciences and in revelatory visions. “Wisdom considers her own achievement, which she has arranged in the shadow of living water in accord with just decision. She did so by revealing through the untutored woman [Hildegard] mentioned above certain natural powers of various things, as well as writing about the meritorious life and certain other deep secrets which that woman beheld in a true vision and which exhausted her”32 (fig. 37).

FIGURE 36

The cosmic wheel, the universe as an egg. Drawing by Hildegard of Bingen, eleventh century. (Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

For Hildegard, the creation of the human being was preordained before creation in God's Wisdom. God also preordained and created the angels as luminous spirits to endlessly praise him. But God intended that the human would be the capstone of creation. This enraged Lucifer, who saw the human created from clay as inferior to his immortal body of light. Rebelling against God, Lucifer fell, with his angelic followers, and took on a dark, bestial body. Located in the gloomy, frozen, northern region of earth, he plots against God and God's favorite, the human being. Human history is defined by this struggle between God and Lucifer, to be overcome only at the end of history.33

Thus, Hildegard mitigates Adam and Eve's guilt for the fall by transferring much of its onus to the jealous rage of Lucifer. Adam was originally born with a shining, uncorrupted body taken from virgin earth and a beautiful singing voice that expressed the music of paradise. In a virginal birth, Eve arose from Adam's side, containing in herself the seeds of all the human offspring who would be born to fill up the intended community of the redeemed (the church). Originally, Adam and Eve would have lain together in a sweet embrace of pleasure that would have transmitted fructifying power between them like perfume. Their children would have been born from Eve's side, as she was born from Adam's side, without debasing lust or the rupture of her virginity.34

But Lucifer sought to destroy humanity by approaching Eve, as the mother of the coming humanity, and offering her a poisoned apple. She took it naively and also gave it to Adam, thereby corrupting their future sexual relations and offspring with sin. But, unlike Lucifer, humans never lose the image of God within and their longing for God. They sin by bending toward the pleasures of their bodies apart from God, but these errors themselves awake in humans a desire for repentance. The love of God subsists in them as their true nature and stirs up remorse.35 Though partially distorted, the harmonies of the cosmos and the body-soul relations remain, to remind humans of their true nature and destiny.

Though Hildegard can speak in terms of ethical dualism, in which body and soul war, the mutual interdependency of body and soul persists. The soul vivifies the body, giving it life, or “greening power,” and the body manifests the work of the soul in it. Hildegard's ethics are based on a balance of forces rather than extremes of body negation for the sake of spiritual perfection. Indeed, she suggests that too much abstemiousness awakens both lust and exhaustion.36 What is needed is to reestablish the harmonious interplay of soul and body.

The relation of Adam and Eve itself images this bond and the intended union of soul and body. While Adam images God, Eve images the humanity of God's son. She represents the body of the coming God-man.37 Eve gives the garment of flesh to every soul, without which it cannot live. Ultimately, she prefigures Mary (or, rather, Mary is Eve's original nature restored), who clothes the Word of God in sinless flesh harmoniously united to God's Word, in whose image the soul is made.

FIGURE 37

Hildegard of Bingen receiving revelations from God's Holy Spirit. Drawing by Hildegard of Bingen, eleventh century. (Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

Hildegard often uses the traditional Christian language that contrasts Eve and Mary, casting Eve as the woman whose disobedience is reversed by the obedience of the Second Eve. To Hildegard, Mary is the restoration and perfection of the good nature of humanity, which Eve originally possessed and would have transmitted to her offspring through virginal childbearing. Hildegard's Mariology reflects a patristic and Carolingian tradition. She does not mention the doctrines that exercised the later medieval church, the Assumption and Immaculate Conception, nor does she have personal revelations of Mary.38

For Hildegard, Mary remains a majestic and somewhat abstract figure, representative of the Seat of Wisdom with the child Christ enthroned in her lap, an iconography derived from the Isis-Horus tradition and a favorite of the Carolingian church. The intimate Mary of later Franciscan spirituality, who sits on the ground with bare feet and a fat, naked babe at her breast, would have been distasteful to Hildegard. Mary's central role is to be the vehicle of the incarnation, the restoration of humanity through giving birth to the Word of God in sinless flesh. Through her virginal body, untouched by sin, she provides the incarnate Word with the garment of uncorrupted flesh that restores the original harmony of God and humanity, of soul and body, of the first parents.

As Eve restored, Mary conceives without sex and gives birth through her side, without rupturing her virginity.39 In her, the original harmony of creation with God is restored, and sin and death are overcome. As Hildegard puts it, in a short praise verse for the Virgin, “Alleluia, O branch mediatrix, your holy body overcame death and your womb illuminated all creatures with the beautiful flower born from the sweetest integrity, the modesty of your closed garden.”40 Mary renews the union of God and materia. In her, divine light streams through the body as it would through a clear glass. In a hymn that encapsulates the drama of original creation disrupted and renewed, Hildegard writes:

O resplendent jewel and unclouded beauty of the sun poured into you, a fountain springing from the Father's heart. This is his only Word by which he created the primal matter of this world, which Eve threw into chaos. For you, the Father fashioned this Word into a man. So you are that luminous matter through which the Word breathed forth all Virtues, as in the primal matter he brought forth all creatures.41

The ultimate theophany of the divine feminine in Hildegard's symbol system is Ecclesia, the church. A much more complex and human symbol than Mary, Ecclesia is both Christ's mother and bride, but she is also the struggling community of Christians in history (fig. 38). In an echo of the Shepherd of Hermas, Hildegard sees the church as preexistent and foreordained before the foundation of the world and yet also being built in the last age of world history as the reborn race of humans who issue from the font of baptism, sharing in Christ's redemptive God-manhood born from Mary.42

FIGURE 38

Hildegard of Bingen's image of Wisdom, the Mother Church. Drawing by Hildegard of Bingen, eleventh century. (Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

As in the Shepherd of Hermas, it is the Virtues, whom Hildegard personifies as female, who build the tower of the church.43 The Virtues represent the synergies of divine and human energy, of divine life meeting human response. The Virtues bring the living stones of new members of the church to build the city of New Jerusalem in history. Hildegard depicts Synagoga, the Jewish people, as a disconsolate bride who has lost her election as God's spouse through failure to believe. Synagoga is something like a communal Eve, but she will be saved through Ecclesia. She will finally repent and be incorporated into the edifice of redemptive humanity at the end of history.44

Echoing a patristic metaphor from Methodius, the church is the bride of Christ, born from his side. She receives as her dowry the blood and water that flowed from his wounded side on the cross. Through her fertile womb, those who inherit the sin of Adam through their mothers, the daughters of Eve, receive rebirth into the redeemed humanity of Christ.45 In a striking image of baptism as womb of rebirth, Hildegard images black babies swimming toward the church, being drawn into her womb like fish gathered into a net. Reborn in the font of her womb, they reappear from her mouth, through which they are instructed in the Word. Their black skins are peeled off, and they are given luminous white baptismal garb.46

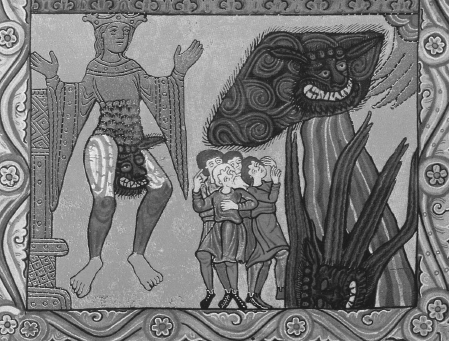

To the image of the church as bride of Christ and mother of Christians in baptism, Hildegard adds imagery from the Eucharistic spirituality so central to medieval Christianity. Ecclesia is a priest who receives the dowry of water and blood from Christ's side in a chalice (fig. 39).47 Offering the bread and wine of Christ's body at the altar, she continually gives birth to God's body as food for reborn Christians.

But the church in history is also the sorrowful mother, weeping for the lost children who have cut themselves off from her by their heresy. She is assaulted by corrupt prelates, who prefer sinful pleasure to virile virtue and fail to protect Christ's bride and their mother. In a striking image, Hildegard pictures the church corrupted by these prelates as a ravished woman from whose vagina emerges a bestial figure with donkey's ears, like an erect penis (fig. 40).48 In a striking reversal of male-female stereotypes, Hildegard typically speaks of the corruption of these male prelates as a fall of the church into “womanish times” (muliebre tempus).49

Although Hildegard accepts the class and gender hierarchies of her society, she subverts their biological literalism. Because the male clergy have succumbed to “effeminate” vices, God has raised a woman prophet (Hildegard) to be God's woman warrior (bellatrix) and to call the church to repentance.50 Hildegard uses the metaphor of effeminacy for male vice but does not portray the vices themselves as female. Rather, vices and the devil are pictured as having human elements combined with animals. They are typically dark, ugly, and bestial; the virtues are feminine, beautiful, and shining with light. While vice-ridden men are “effeminate,” God can raise up weak women to become virile and manly, paragons of divine power and teachers of virtue.

The final crisis of the church in world history is still to come, Hildegard declares, though it is anticipated in these corrupt, “womanish” times. The final paroxysm of world history will take place with the birth of the Anti-Christ. In a reversal of Mary's role, he will be born from a harlot but feign a virgin birth in a diabolic parody of Christ.51 Although he will lead many astray, his downfall is sure. When he is defeated by the returning victorious Christ, the church and Christ will finally be united in loving communion. This can happen only when the full number of humans pre-ordained from the beginning of the world are born and reborn in baptism.

FIGURE 39

The crucifixion of Christ and the sacraments. Drawing by Hildegard of Bingen, eleventh century. (Photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY)

FIGURE 40

The struggle against evil within the church. Drawing by Hildegard of Bingen, eleventh century. (Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

In the final salvation in the heavenly new creation, the soul will receive back its beloved body, without which it cannot function. Then the final cosmic harmony of God and materia will be completed.52 Although this time is still in the future, it is prefigured now in the communities of virgins, such as the one in Hildegard's own abbey. Clad in shining white garments and crowned with golden crowns, their sweet voices are raised in songs of praise that prefigure the community of paradise restored and perfected in the heavenly new creation.53

FEMININE SYMBOLS IN CISTERCIAN AND BEGUINE LOVE MYSTICISM

Although Hildegard did not focus on the bridal relation of the soul to Christ, a major stream of contemplative mysticism made this central, using the Song of Songs as its primary text. Specifically, Bernard of Clairvaux's commentary on this text serves as a foundational exposition of Cistercian mysticism. It is then useful to compare his work with the bridal mysticism of three female mystics of the thirteenth to early fourteenth centuries, Mechthild of Magdeburg (1208–1294?), Hadewijch (c. 1250), and Marguerite Porete (d. 1310). All three were Beguines, members of new, informal women's communities, often suspected of heresy (Marguerite Porete was burned as a heretic) and thus far removed from the established Cistercian world of Bernard, who lived and wrote more than a century earlier.

BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX AND BRIDAL MYSTICISM

Bernard of Clairvaux's bridal mysticism is distinguished from the Neoplatonic allegorical exegesis of Origen and Gregory Nyssa (see chapter 5) by its much greater appeal to the emotions as a positive aspect of the soul that draws it to God. Although Bernard alludes to both the church and the Virgin Mary as brides of Christ, the soul is the primary reference for understanding the bridal relationship of humans to God. For Bernard, the Song of Songs so perfectly describes the relation of the soul to God that he speaks of it as the “book of our own experience.”54 The soul, made in the image of the Word of God, has a natural affinity for the second person of God. Bernard can even speak of the soul and the Word as sister and brother under God the Father, as well as bride and bridegroom.55

The soul has been alienated from the Word through sin, but it has not lost this natural affinity, which is its created nature.56 Yet, in its alienated state, it cannot turn back to God of its own will. Rather, it is God's love that awakens the love of the soul for God. The initiative for our journey to God always remains with God. But this is more an awakening of a potential that is still present than a new creation of what has been lost.

She who loves is herself loved.... The love of God gives birth to the love of the soul for God and his surpassing affection fills the soul with affection and his concern evokes concern. For when the soul can once perceive the glory of God without a veil, it is compelled by some affinity of nature to be conformed to it and be transformed to its very image.57

Central to Bernard's understanding of psychology is the need to integrate love and knowledge. Without love, knowledge is dry and mere external theory. But love without knowledge is heat without light. Only when knowledge and love are united and mutually transformed is there true knowledge, a real possession of and participation in the thing known.58 This union of knowledge and love is true of our relation to others as well as our relation to God. In the favorite text of 1 John 4:16, “God is love,” there is no knowledge of God without love of neighbor.

This emphasis on love of neighbor as well as love of God leads Bernard to a partial reversal of the hierarchical relation of action and contemplation in monastic life. Bernard does not see action as the inferior sister of contemplation, as in the traditional imagery that compared Martha, as a symbol of the active life, to Mary, as a representative of the contemplative life. Nor does he see the active life only as ascesis, or purgation, in preparation for theoria, or contemplation. Rather, Bernard creates a trilogy of Lazarus, Mary, and Martha and insists that they all must live in mutual interaction in one household. Lazarus is the ascetic purgation of vice, and Mary is contemplation of God, while Martha is active love, expressed in service to others.59

Again and again, Bernard insists that, much as monks might like to spend their time in contemplative ease, they must break this off in order to engage in active service to others. Bernard has many kinds of service in mind—for example, interrupting a sermon to serve guests who have come to the monastery.60 Service can also mean care of the souls of other monks within the monastery. It is the work of preaching, an activity that was becoming more important in the twelfth century.61 It also includes works of mercy to the poor, even love for enemies. Love of God is expressed both in the transformed self seeking union with God and in the gifts of outer service to others. Both are expressions of the work of the Holy Spirit. The second cannot be neglected for the sake of the first.62

In an extraordinary image, Bernard exegetes the opening phrase of the Song of Songs, “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth,” as both the bridal embrace of soul and Word and also the bride's impregnation, which makes her a mother, filling her breasts with milk to feed her children. He continually directs abbots, preachers, and administrators to be mothers of their flocks and not tyrants. He interprets the work of caring for others as motherly nurture, feeding them an overflowing milk from the breasts of those who have been kissed by the embrace of the Word: “The filling of the breasts is proof of this. For so great is the potency of this holy kiss, that no sooner has the bride received it than she conceives and her breasts grow rounded with the fruitfulness of conception, bearing witness, as it were, with this milky abundance.” This “milky abundance” testifies to the presence of God as an infusion of grace, which takes place when prayer is transformed from dry routine to an experience of overflowing love. But it must be expressed in service to others, not merely in cherishing one's own inward experiences: “Far better the profit in the breasts you extend to others than in the embraces that you enjoy in private.”63

While Bernard exhorts male church leaders to be mothers in relation to those under their charge, his language is not without misogyny toward women and what they represent. Although the bride is spoken of as “fairest of women,” her femaleness indicates that she belongs to the sinprone body: “For I think that in this passage, under the name of ‘women,’ He speaks of carnal and worldly souls, which have in them no manly force, displaying nothing constant or generous in their actions, but of which the whole life and character is soft, remiss and, in a word, womanish.”64

Interestingly enough, he also characterizes monks as soft and womanish and warns them against criticizing bishops, who live a far laxer life in respect to the pleasures of the body. Bishops, Bernard scolds, actually live a harsher life and must shoulder difficult responsibilities in society, which are beyond the capacities of weak monks:

Let us admit that our powers are unequal to the task, that our soft effeminate shoulders cannot be happy in supporting burdens made for men. It is not for us to pry into their business but to pay them respect. For it is surely churlish to censure their doings if you shun their responsibilities; you are no better than the woman at home spinning, who foolishly reprimands her husband returning from the battle.65

Bernard reminds his monks of the scriptural passage, “Better the wickedness of a man than a woman doing good” (Wisdom of Jesus ben Sirach 42:14),66 to put their womanish virtues in their proper place in relation to the superior virility of bishops.

Such passages remind us of the deep ambivalence toward the feminine in Bernard's monastic cultural symbolism. The male monk may imagine himself a beloved maiden whose breasts fill with milk when kissed by a handsome bridegroom and may see his pastoral responsibilities as analogous to those of nursing mothers. But females nonetheless symbolize a carnality linked to vice and a weak softness that should abase itself before virile manliness, even in the male-male relation of monk to bishop.

Such imagery suggests that we should exercise some care in assimilating twelfth-century male monastic understanding of the bridal soul into modern Jungian valuing of the feminine anima. Ultimately, for Bernard, bodily images for God, such as feet, hands, and mouth, are figures of speech;67 and probably, for him, the notion of the soul as female would have fallen in the same category. It is appropriate as an expression of the dependency of creature upon creator, however much their love may be hymned as mutual. But this does not easily translate into a general valuing of the feminine as a distinct aspect of the soul.68

THREE BEGUINE MYSTICS AND MYSTIQUE COURTEOISE

The three Beguine mystics discussed here drew on the male tradition of bridal mysticism based on the Song of Songs, but they transformed it by fusing it with the secular tradition of courtly love. This created a new genre of mystical love that Barbara Newman has called mystique courteoise. 69 In theory, the two kinds of love were incompatible. Christian ascetics since Origen had labored to distinguish the spiritual love of God from sexual passion. But, from the twelfth century, the two had begun to flow into each other. Poets of secular love had adopted elements of religious language, while contemplative writers, such as Richard of St. Victor, recognized that sexual passion and spiritual love passion, though morally opposite, were psycho-logically similar.70

The union of the two genres in mystique courteoise, as exemplified in the works of the three Beguine mystics, created more vivid erotic language, more violent paradoxes of love and despairing longing unto death, and a gender fluidity for both lovers, God and the soul. The soul was pictured as the bride longing for and entering into a love union with her lord but also as the warrior-knight in quest of the distant lady. God was pictured in traditional male language as father, son, and spirit but also as lady love, enthroned as queen of heaven.

While male mystics such as Bernard pictured themselves as brides and impregnated mothers, with full breasts nursing those in their care, female mystics could see themselves not only as female brides but as male lovers tormented by the disdainful queen. Significantly, Bernard's image of pregnant, nursing mothers is absent in the writings of the women. The three female mystics did venerate the Virgin Mary as a key theological symbol. Hadewijch, for example, imagined herself becoming Mary, giving birth to Christ, and imitating her suffering motherhood; but she does not connect this with mothering her young Beguines.71 Moreover, it is Mary Magdalene who appears as the role model for the love relation of the spousal soul and Christ.72

Mechthild of Magdeburg For Mechthild of Magdeburg, the creation of the soul by God the Trinity was the primal work of God's love at the beginning of creation. Contrary to the orthodox image of God the Trinity as self-sufficient, God is incomplete without the soul as beloved and bursts forth to create and give himself to her: “In the Jubilus of the Holy Trinity, when God could no longer contain Himself, he created the soul and in his immense love gave himself to her as her own.”73

Mechthild imagines the Trinity engaging in conversation after the creation of the angels. The Son longs to create man in his image, even though he foresees tragedy in this act of love. The Father agrees, desiring one who will love them in return:

The Father said, “Son, a powerful desire stirs in my divine breast as well, and I swell in love alone. We shall become fruitful so that we shall be loved in return.... I shall make a bride for myself who will greet me with her mouth and wound me with her beauty. Only then does love begin.” Then the Holy Spirit spoke to the Father: “Yes, dear Father, I shall deliver the bride to your bed.”74

The fall of the soul through the disobedience of the primal parents deprived the Father of his bride, but his anger was curbed by Eternal Wisdom, together with Mary. Mechthild sees Mary as the one unfallen soul, who becomes God's bride during the long ages between the fall and the incarnation: “The Father chose me for his bride, that he might have something to love, for his darling bride, the soul, was dead. The Son chose me as his mother.” Mary is viewed as the preexistent church, who nurtured God's people through the ages and comes to fruition as mother of the Son's humanity. Through the incarnation, the soul can be restored as God's bride. Mary is both the unfallen counterpart of the bridal soul and Mater Ecclesia, whose full breasts suckle both the prophets and the Christian people.75

The soul is called the Father's daughter, the Son's sister, and the Holy Spirit's friend, bride of the whole Trinity. God's love for the soul is depicted with explicit eroticism. The bride clothes herself in virtues in preparation for the love dance. But when she enters the bridal chamber, her divine lover bids her strip off her clothes. When the soul becomes “naked,” perfectly conformed to God, external practices of virtues need no longer come between God and the soul. “He surrenders himself to her and she surrenders herself to him,” a love union that anticipates their “shared lot” in eternal life without death.76

In the manner of a courtly lover, God is depicted bending his knee to Lady Soul. God “surrenders himself to her power.” After their union, God is still as lovesick for her as he always was (unlike human love, which becomes exhausted in union). The soul tears her heart in two to put God in it and thereby becomes a soothing balm for God's desire for her.77

Yet the love relation with God is not all sweet ecstasy, for Mechthild. Mostly it is pain and suffering, a suffering in estrangement from God, which expresses the finite, bodily condition and also the persecutions of those who do not understand her way of life. But by willingly accepting Lady Pain, Mechthild also participates in the sufferings of Christ and herself becomes Christ. Like Christ, her head is struck with a reed; she is forced to drink vinegar rather than wine; she is hung on high and descends into hell, consoling dejected souls; she is buried, “enjoying a lament of love with her Lover on the narrow bridal-bed”; rises on Easter day; passes through the shut doors to her disciples; and finally ascends to heaven.78 As sharer in the sufferings of Christ's humanity, the soul becomes co-redeemer with Christ.

Hadewijch We turn now to Hadewijch, a Flemish Beguine who was a contemporary of Mechthild.79 Hadewijch uses several voices in her exploration of her love relation to God. In her Poems in Stanzas, she is the knight errant engaged in high adventures and difficult trials in order to win the favor of Lady Love. In these poems, she assumes all the affects of the male courtly lover seeking to conquer the distant lady. She lays siege to the lady's castle. She complains of the lady's fickleness and cruelty. She even accuses the lady of treachery, of cheating in duels and at cards, and threatens to abandon her. But she returns again to pursue her “suit.” She imagines herself riding a proud steed, only be unhorsed.80 She speaks even of love's madness, of going mad with love. She sighs and proclaims her sufferings for the sake of love, speaking of this contest in the courtly language of a “school of love.”81

But she ever returns to her proclamation of fidelity and longing to be one with the lady, imagining their final union in which they “flow through each other”: “Let your whole life be holy affliction until you are master of your beloved.... You shall row through all storms until you come to that luxuriant land where Beloved and loved one shall wholly flow through each other, of that, noble fidelity is your pledge here on earth.”82

In her visions (written before the lyrics, when she was young), Hadewijch primarily speaks of herself as a bridal soul, who longs for her beloved and imagines herself being led to the apocalyptic wedding with him in the New Jerusalem. Here, the identity of the bridal soul merges with that of the church, through whom the whole community of heaven lives:

Then I heard a Voice loudly crying, “New Peace be to all of you and new Joy! Behold this is my bride, who has passed through all your honors with perfect love and whose love is so strong that, through it, all attain growth!” And then he said: “Behold, Bride and Mother, you like no other have been able to love me as God and Man!... Now enjoy fruition of me, what I am, with the strength of your victory, and they shall live eternally contentedthrough you.”83

In another vision, Hadewijch sees herself adorned with all virtues, escorted through the heavenly city to union with the divine Countenance, enthroned on the disk of the unfathomable unity of divine Being. Through her virtues, she has conformed to and been assimilated into the perfect humanity of Christ, and now she comes into her heavenly kingdom as God's bride. The eagle (of her revelation) cries out: “‘Now see through the Countenance and become the veritable bride of the great bridegroom and behold yourself in this state.’ And in that very instant I saw myself received in union with the One who sat there in the abyss upon the circling disk and there I become one with him in the certainty of unity.” In this vision, Hadewijch, as bridal soul, is “swallowed up” into God. “Then I received the certainty of being received, in this form, in my Beloved and my Beloved in me.”84

In her poems and visions, Hadewijch personifies Love as female in a way that merges Christian caritas, the love nature of God as described in 1 John 4:16 (“God is love”), with Frau Minne, the eros of courtly love. Personified Love is simultaneously the subjective experience of love of God in the soul and the object of this love, God. Or, one might say, Love is the meeting point and merger of the two, the soul's experience of love and God's Being as love. For Hadewijch, Love is not only the circulating energy that unites the three persons of the Trinity and takes the soul into its inner circle of love; it is also the unity or essence of Being in which the three persons of God subsist.

Love can thus be imagined as a goddess enthroned upon the being of God:

I saw in the eyes of the Countenance a seat. Upon it sat Love, richly arrayed, in the form of a queen. The crown upon her head was adorned with the highworks of the humble.... From Love's eyes proceeded swords full of fieryflames. From her mouth proceeded lightning. Her countenance was transparent, so that through it one could see all the wonderful works Love has ever done and can do.... She had opened her arms and held embraced inthem all the services that anyone has ever done through her. Her right side was full of perfect kisses without farewell.85

Barbara Newman speaks of this vision of Love as “the verbal icon of God as female.”86 But enthroned Love here stands for more than God in God's original being prior to creation. Love is the ultimate apocalyptic completion of God's relation to creation in its redemptive union, when God shall be “all in all” (1 Cor. 15:28). Hadewijch sees in a lightning flash this ultimate nature of Love, God “all in all” in union with creation. In this revelation, Love herself cries out, “I am the one who holds you in my embrace! This is I. I am the all! I give the all!”87

Marguerite Porete In Marguerite Porete, we find the paradoxes of Beguine mysticism pushed to a radical extreme in a way that became intolerable to the official church of the fourteenth century. Marguerite wrote her book The Mirror of Simple Souls between 1296 and 1306. She was arrested several times on suspicion of harboring the heresy of the “free spirit,”88 and her book was burned by the Inquisition. But she continued to circulate it and sent it to three noted scholars, all of whom approved it.89 She was arrested again in 1309 and held in prison for a year and a half, during which she refused to give any testimony. The Dominican Inquisitor extracted a list of articles from her book, out of context, and sent them to the theological regents of the University of Paris, who condemned them. She was executed in the Place de Grève on June 1, 1310. But her text continued to circulate in Old French, as well as in Latin, Italian, and Middle English translations, under the cover either of anonymity or the names of more established male mystical writers.90

Toward the end of her book, Marguerite lays out her theory of seven stages of spiritual ascent, which she has presupposed throughout the text. In the first stage, the soul is touched by the power of God's grace. Stripped of the power to commit sin, she vows to observe all the commandments for the rest of her life. In the second stage, the soul goes beyond the commandments and mortifies nature, observing the counsels of evangelical perfection exemplified by the life of Jesus Christ. In the third stage, the soul's spirit is sharpened “through a boiling desire of love” and seeks to kill her own will in order to live only by the will of God. In the fourth stage, the soul experiences an ecstasy of absorption in divine love, relinquishing “all exterior labors and obedience.” In the fifth stage, the soul falls into total wretchedness, experiencing the nothingness from which she was created, in order to annihilate any self separate from God and thus to live love, not as herself but as God living and willing in her. In the sixth stage, the soul becomes totally transparent to God with no impediment of a separate self separating her from God. The seventh stage is unknown. It is the ultimate state that “love keeps within herself in order to give us eternal glory of which we have no understanding until our soul has left our body.”91

Marguerite speaks of these stages of spiritual ascent as entailing three deaths—a death to sin, a death to nature, and finally a death to spirit itself as a separate existence from God's spirit.92 The Mirror is written as a dialogue among Reason, Love, and the Soul, all personified as female. Love declaims the revelations of the higher stages of life, while Reason represents conventional virtues and the rationality of the official church, who is constantly amazed by the daring teachings of Love. The Soul speaks by questioning Love about the meaning of her teaching and about what new heights of spiritual ascent she should scale.

For Marguerite, Reason is spiritually inferior to Love and represents the first and second stages of the life of established morality and monastic piety. Reason is spoken of as “one-eyed,” being incapable of understanding the higher reaches of ecstatic union and annihilation of the soul in God. She is scandalized by talk of these higher stages of spiritual ascent, which threaten her institutional system.93

Reason is particularly horrified by Love's talk of leaving behind the virtues, discarding the external props of the institutional church: Masses, sermons, fasts, and prayers. The Soul declares that she was once servant of these virtues but now is freed of their dominion:

Virtues, I take leave of you forever. I will possess a heart most free and gay.... I was once a slave to you, but now am delivered from it. I had placed my heart completely in you, you know well. Thus I lived a while in great distress. I suffered many grave torments, many pains endured. Miracle it is that I have somehow escaped alive. This being so, I no longer care. I am parted from you. For which I thank God, good for me this day. I am parted from your dominions, which so vexed me. I was never more free, except as departed from you. I am parted from your dominions, in peace I rest.94

This inferiority of Reason and the virtues signals the foundational hierarchy of Marguerite's system of spirituality, the hierarchy of Holy Church the Great over Holy Church the Little. Holy Church the Little lives by reason, the virtues, and external observances. Those who live at this level will be saved through God's gracious incarnation in Christ, so they are not excluded from paradise in the end. But they are incapable of understanding or instructing the elite of the “free souls,” of Holy Church the Great, who have passed on to the higher stages of spiritual life. Rather, the “free souls” mediate this knowledge to Holy Church the Little, who should submit to their instructions.95

Marguerite speaks of two kinds of souls who fall into the lower levels of spiritual life and have not attained the state of the “unencumbered soul.” These are the “lost souls” and the “sad souls.” The lost souls have no clue about the higher life and are hostile to any intimation of its existence, whereas the sad souls know that there is a higher stage of life but do not know how to attain it. Marguerite admits that she was long one of these “sad souls.”96 Clearly, it is precisely this doctrine of the spiritual aristocracy of “free souls” above “Holy Church the Little” in which Marguerite pushed the limits of the church's acceptance of mysticism.

Mystical thought always presented the danger of transcending the church's institutional means of grace in favor of an independent, direct relation with God. Marguerite not only hinted at but flaunted this transcendence of the institutional church. Hildegard of Bingen, Mechthild, Hadewijch, and many other mystics denounced the corruption of the clergy and criticized clerical inability to understand their pursuit of a higher spiritual life. But Marguerite goes beyond such critiques of corrupt or blind clergy to a systematic characterization of the institutional church as inferior, while the others were always careful to at least pay lip service to its authority.

Marguerite's confidence in the possibility of the soul's transcendence of its own separate self to live “no longer as I, but God living in me” (reinterpreting Paul, Gal. 2:20) lies in her ontology of the Being of God in relation to creation. Marguerite builds on the longstanding Christian view that creation itself has no independent substantive existence apart from God's Being.97 Apart from God's Being, creation is Nothing. Creation was taken from this Nothing to become “something” through God's creative act. Becoming an “annihilated soul” is literally a return to that Nothing, which is the soul's reality apart from God's Being. In that leap into Nothingness, the soul also ceases to have a separate existence and is united with the Divine Being, the only Being that truly is.

This understanding of Nothingness as the reality of creatures apart from the All of Divine Being underlies Marguerite's constant paradoxes, in which the Soul, denying her will and finally her separate existence, becomes Nothing, thus becoming All. She no longer lives, loves, or wills of herself; but God lives, wills, and loves in her and as her, “without her.” This fall into the abyss of Nothingness, in which the Soul becomes All, while always aware of being Nothing, is paradoxically the final act of the self. But it can never happen as long as the Soul has a self that wills apart from God. Thus Love says to the Soul: “If you understand perfectly your nothingness you will do nothing and this nothingness will give you everything.... As God has transformed you into Himself, so also you must not forget your nothingness. That is, you must not forget who you were when He first created you.”98 This loss of will and separate existence cannot happen through an act of will of the self. It is purely a gift of grace, in which God transforms us into himself. Marguerite's mystical theology is one of divine grace without any human “works.”

Yet Marguerite is acutely aware that all “talking about” this transformation, including the words of her own book, falls on the side of a separate self that still acts as a self, and not as God working and willing in her. Thus, compared to the actuality of being in God, all the words of her book are “lies.” They talk about something that she has not yet accomplished or, rather, that has not yet happened in her. She is still a “sad soul,” who knows of a higher life but has not yet been transformed into it. The name of this God that she glimpses from a distance is poignantly called “ravishing Farnearness,”99 a deity that is infinitely distant, while being closer to one-self than one is to oneself.

In the first chapter of her book, Marguerite speaks of herself as a “maiden, the daughter of a king,” who falls in love with a noble king, Alexander, whom she had never seen but could only imagine. She has an image painted of this beloved, which represents both her love and the object of her love, and she contents herself with loving this portrait, in the absence of the reality of her beloved.100 Marguerite's Mirror of Simple Souls is her portrait of the imagined king that mirrors but is not the reality of the loved one.

Marguerite's acute sense that her words “about” or her portrait “of” this beloved one ever fall on the creaturely side of the separate self, a self that is not yet “anni-hilated,” perhaps explains her behavior in the hands of the Inquisition. She refused to give any answer to their inquiries, maintaining a silent, noble resolve to the end, which brought tears to the eyes of the spectators as she went to her fiery death. In willing her own annihilation, she also testified to her faith in her ultimate transformation, in which she would become, finally and really, no longer “I, but God living in me.” The Inquisition's act of annihilating her was perhaps, for her, her final perfection in Love in and as God.

MOTHER WISDOM AS THE SECOND PERSON OF THE TRINITY: JULIAN OF NORWICH

From Marguerite Porete's quest to become an “annihilated soul,” culminating in her bodily destruction, we turn with some relief to the “homier” views of a fourteenth-century recluse, Julian of Norwich. Yet Julian began her spiritual path with a wish to share Christ's crucifixion to the point of death. As a young woman, she prayed for three gifts—to see Christ's dying on the cross, to experience a sickness to the point of death, and to experience three wounds: contribution, compassion, and complete longing for God. Starting on May 8, 1373, when she was thirty and a half years old, Julian's prayers were answered. She lay at death's door for seven days, culminating in sixteen visions of Christ dying on the cross. At the point of death (his death and also hers), Christ was suddenly transformed to risen life, and she too was restored to health.101 Julian spent the rest of her life meditating on the meaning of these visions. It was probably at this time that she decided to begin the life of an anchoress (a solitary recluse enclosed in a room attached to a church, where she could both hear Mass through a window and counsel others).102

Julian uses neither bridal mysticism nor the language of courtly love. She does not describe the soul as a bride or personify it as a female, nor does she describe God as a lover. There is no appeal to personified Love. Rather, her language for the relation of God to humans is more familial, paternal and maternal. The self is a beloved child or servant of a kindly lord. Julian's major theological problem is theodicy, reconciling her understanding of God as loving and forgiving with the church's teaching on the final damnation of unrepentant sinners. She also seeks to understand how God can allow the prevalence of evil and violence, such as she saw around her in her society.

Julian addresses this problem by a reinterpretation of sin and God's response to sin. Following a well-trodden path from Augustine, Julian sees sin or evil as having no real substance. Rather, it is absence or privation. God is pure goodness. Since humans have their source in God and are God's image, in their true created nature, or “substance,” they too are completely good. But in their actual existence, or what Julian calls their “sensuality,” they become separated from God. This separation is experienced by fallen humans as both pain and shame. They become enclosed in their fear and guilt and are convinced that God is angry at them. They become entrapped in this fear of God's anger and are unable to rise and realize that God is not angry at them but continues to love them and wish them well.103

Christ takes on human “sensuality” in the incarnation, thus becoming humanity's substitute “servant” and bearing all human distresses. Standing before God as our representative, Christ carries all the fallen servants with him and enables us to see that we are still loved by God, despite our mistakes. For Julian, the fallen condition is itself painful and distressing, rather than pleasurable, and thus serves as “medicines” that stir us up to seek to overcome this condition.104 But this solution to fallenness still maintains the possibility that many will not accept their redemption and will not open their eyes to God's enduring love, and so will be damned eternally. Julian cannot openly deny the church's teachings about hell, but she has a guarded hope that, in the end, no souls will actually be found there. God will work the ultimate miracle of grace, and all souls will be saved. In the end, “all will be well, all will be very well.”105

This faith in God's enduring love and kindness is expressed in her combined fathering and mothering language for God: “Thus in our making God almighty is our kindly Father, and God all-Wisdom is our kindly Mother, with the love and goodness of the Holy Spirit, which is all one God, one lord.”106 Julian brings mothering language into the Trinity by a recovery of female-personified Wisdom, identified with the second person of the Trinity as mother. Wisdom is our mother as agent and means of creation and hence as the one through whom we are created “substantially” as children of God. As incarnate Christ, the second person is also our mother as the one who takes on our body and redeems us, bringing us to reborn life. The incarnate Christ, in whom we are birthed anew and fed in the Eucharist, is then our mother “sensually.” Julian draws on Christ's work in birthing anew and feeding us, not to image the church but rather to image Christ as mother. Thus, Julian says:

Furthermore I saw that the second Person who is our mother substantially, the same dear person is now become our Mother sensually. For of God's making we are double; that is to say, substantial and sensual. Our substance is that higher part which we have of our Father, God almighty. And the second Person of the Trinity is our Mother in kind, in our substantial making—in whom we are grounded and rooted, and He is our Mother of mercy in taking our sensuality. Thus our Mother means for us different manners of his working, in whom our parts are kept unseparated. For in our Mother Christ we have profit and increase; and in mercy he reforms and restores us, and by the power of our passion, his death and his uprising, oned us to our substance. Thus our Mother in mercy works to all his beloved children who are docile and obedient to him.... Thus Jesus Christ who does good against evil is our very Mother. We have our being of him, where every ground of Motherhood begins, with all the sweet keeping of love that endlessly follows. As truly as God is our Father so truly is God our Mother.107

With these famous lines, Julian restored mothering language to the nature of God, language that had largely disappeared for Christians with the New Testament masculinization of Wisdom as Christ the “Son” and the repression of early Christian images of God as father, mother, child (see chapter 5). Here, Mother Wisdom is identified as the second person of the Trinity and incarnate Christ, who is our mother both as creator and as recreator of our humanity.