SO FAR, WE HAVE TALKED ABOUT A PRETTY WIDE RANGE OF ISSUES. MANY OF THEM MAY BE NEW TO YOU SO WE WILL RECAP BEFORE DIGGING INTO AN EXAMPLE DRAWN FROM STRATEGY. WHAT DID WE TALK ABOUT OVER THE LAST 160 PAGES OR SO?

-

The importance of flow

in a highly scaled business where velocity is a key.

-

Ways of learning and the paramount importance of beliefs and social interaction.

-

Making the customer visible.

-

The three phases of culture (industrial, services, and flow

).

-

Challenging the executive suite.

-

The overwhelming importance of pushing visualisation to extremes in order to provide a focal point for interaction and decision-making.

-

The sequencing of Walls.

-

The new qualities of leaders.

-

What a primary flow

team should entail from Wall to Wall, Portfolio to Project to KanBan.

Now, we’ll look at digital transformation and strategy through an example. In doing so, we will reiterate some of our thoughts about how to learn. But we are also going to talk about the next important skills and philosophies in

flow

:

The importance of

flow

in keeping delivery of value going and resisting the drift that big projects create.

The importance of

flow

in keeping delivery of value going and resisting the drift that big projects create.

The nature of social interaction as a complex learning system where everyone has a voice.

The nature of social interaction as a complex learning system where everyone has a voice.

BREAKING BREAD WITH REALITY

Earlier we talked about the typical priorities of the executive suite. One frequently stated objective of top executives is “Put the customer front and centre”. We also, somewhat facetiously, said that executive offsites continuously create new priorities by burying the ones from the previous year. Rather like a medieval city that gets submerged over time when you Walk the Wall and Bring Out the Dead, you find many priorities that deserved burying are still in circulation.

The importance of the customer, however, will be around for a long time to come. But it needs to be made operational in different parts of the business. Many new ideas are emerging around that. As we find customer experience inescapable, the large consultancies have inevitably moved in.

You may remember earlier we discussed

flow

in terms of the activity and knowledge that feeds into the Executive Portfolio Wall, the place where priorities are translated into projects. Walls for strategy and culture are not fast changing and dynamic in the way that Project Walls are. Rather, they are a repository of what the company is learning.

Companies are launching digital transformation projects with no real sense of the before and after, nor of transformation as a work in progress. They expect a result like a single view of the customer when, in reality, what they need is a continuous dialogue about customers.

In this example, the company’s objective is to get the customer front and centre. Doing so needs a critical transformation in how they use data. They want to launch one big customer-centric data project. The issue this raises for

flow

advocates is how to apply

flow

principles to big transformation projects. Our priority is to keep on adding value - in small discrete steps. But many big projects put value deep into the future, a strategy full of risk. Let’s see how we can think about this differently. Think back to

Chapter 5

where we dummied up this short list of executive’s top five priorities:

Customer front and centre. Going digital.

Customer front and centre. Going digital.

Offence: delivering upside through new market entry; increased share of wallet.

Offence: delivering upside through new market entry; increased share of wallet.

Defence: cost focus / rationalisation.

Defence: cost focus / rationalisation.

Prioritising innovation and change

Prioritising innovation and change

Now, the CEO of a fictional company has read about new techniques that give a single view of the customer and thinks this is great, so the “customer front and centre” priority gets restated as a technical one. The big priority becomes how to get a single view of the customer from all the data that the company hosts in its various servers. The priority is suddenly not the people or the customer. It is the technology of big data. We are, potentially, on our way to another tech-fest. Is technology the best way to get the customer front and centre? Maybe not, but we are about to make that idea a normative problem.

MY GREAT BIG FAT NORMATIVE PROJECT PROBLEM

We refer to the single view of the customer (SVOTC) as a normative problem because, like other choice phrases, it gets the same endorsement across many different industries. It quickly becomes the norm in conversations about innovation. That means many areas of work become normative whether they are true or not. It’s a corner we keep painting ourselves into.

Consulting companies like IBM and Accenture are often the source of new business norms. They have great thought leadership but they also have a pressing need to keep finding work for highly paid consultants. They survive by codifying new platforms or technologies into business concepts that they can own and sell aggressively in order to put thousands of their people to work.

Conversely, in the face of the jargon deluge, companies struggle to discern what they really, truly need. Doubt and uncertainty are a consequence of being surrounded by very powerful vendor communities whose members devise new concepts and then successfully propagandise them into the market

The purpose of

flow

in this situation is to maintain a sense of proportion and to find ways to improve the company, even as decisions on big initiatives work their way through procurement. To take small steps towards value can be a sanity check, showing the executive team that the company can make progress without spending millions of dollars. Whether it can truly help resist the big vendor sales’ machine is another question.

Flow

can at least keep the focus on the real objectives: continuous improvement in customer value.

The argument for SVOTC, the one that sets up the big project, goes something like this:

“We need a single view of the customer, an investment aimed at producing far better opportunities to upsell and cross-sell as we mine data effecively.”

Concepts like SVOTC are simplifications of complex organisational change tasks. They carry a huge amount of baggage with them, not least that most companies have no idea what data they have or how to make it usable. Implicit in the above statement, then, is the expectation that getting a single view of the customer will take some years and many millions of dollars.

Other issues that lurk in the background include:

We already mentioned that these concepts are designed by vendors, such as consulting firms and tech platform firms, which means there is a huge marketing push behind them that is difficult for executives to resist. The concepts very quickly take on the character of “must have or be left behind.” In our experience, many SVOTC platforms fail because they are implemented too quickly and with inadequate process redesign.

These are huge disruptions and come with enormous requirements because they involve introducing new platforms that need a large measure of integration. Most organisations will have multiple platforms where user data is kept, and most will not know what data they keep. On top of that, the different platforms will not talk to each other, and so creating a SVOTC from this is quite a challenge. Many CIOs want to move away from these big projects but they can become irresistible because the pitch is made to the CEO.

Multiple different silos in an organisation create a sense of ownership and competition over the project and its outcomes. Some of the data might “belong” to marketing, while the CIO may think his department owns the technology. The chief data scientist, meanwhile, may think the entire project is hers. All want kudos from a good outcome and want to avoid odour from a bad one. All of this creates negative competition and places constraints on collaboration.

Very often, SVOTC projects require some kind of data-normalisation process and the creation of some kind of reference-data layer, neither of which is trivial. In AI, data normalisation can be 90 percent of the cost of a project.

These are all difficult problems to deal with. However there is an upside to the discussion around this, even if SVOTC is not achieved. SVOTC represents an opportunity to move technology and data to the cloud, introducing the ability to reduce cost and increase the pace of innovation. It presents an opportunity to simplify and future-proof the technology base but that is our gain not the customers.

THE FLOW-THINKING RESCUE DIET

Most organisations become normative in their thinking or veer towards a general consensus that sends damaging vibes down from the C-Suite. The

flow

solution is different. We think how can we protect our mission of continuously improving how we create value. OK, we don’t want to duck SVOTC but nor do we want to be overrun by it. Big projects create big gaps in value creation. We’ve seen these big projects once too often. At their very mention, alarm bells will be ringing for anyone over 25 years of age.

In

flow

, our priority is customer value and it does not take a genius to see that SVOTC is an investment that will benefit us, the company, without any clear reference point for how it will benefit the customer. The real answer of course is that customers get to buy more of our products or services. So how does that benefit them? It’s a matter of integrity that we find out.

In

flow

, as well as asking the customer’s questions, we also focus on the short-term gains. Just a step or two at a time that will help us to learn more about this new SVOTC challenge and add value as we take the first steps towards it.

SVOTC is part of the larger creative challenge of understanding how to function as a digital business, how to transform, and how that helps build customer satisfaction and long-term, loyal relationships.

Imagine, then, a section of the Customer Wall devoted to SVOTC. The concept can be broken into three areas (or more, if you wish):

-

Semantics:

What do we really mean by this term?

-

Resources:

What will be the overall cost?

-

Vision:

How does it fit with or alter our vision?

This should come first, so we can figure out what SVOTC actually means.

Take a few index cards and gather a few colleagues around. SVOTC means:

A data-driven method of cross-selling or upselling to customers.

A data-driven method of cross-selling or upselling to customers.

Potentially a lower cost of sale and therefore a higher margin.

Potentially a lower cost of sale and therefore a higher margin.

An opportunity to segment the market in new ways through data.

An opportunity to segment the market in new ways through data.

The potential for customer loyalty but also the potential to create problems around privacy.

The potential for customer loyalty but also the potential to create problems around privacy.

Potentially transitioning away from advertising and mass marketing to what’s becoming known as “the market of one” (i.e., getting enough data to sell at scale to each individual).

Potentially transitioning away from advertising and mass marketing to what’s becoming known as “the market of one” (i.e., getting enough data to sell at scale to each individual).

Potentially buying a vendor platform or solution, even if we may not need one. Creating an imbalance in departmental budgets.

Potentially buying a vendor platform or solution, even if we may not need one. Creating an imbalance in departmental budgets.

Probably an opportunity to extend data-capture to the customer call centres, which will anyway be buying bots to automate customer transactions and build new data sources.

Probably an opportunity to extend data-capture to the customer call centres, which will anyway be buying bots to automate customer transactions and build new data sources.

An opportunity to move infrastructure to the cloud and retire some legacy technology.

An opportunity to move infrastructure to the cloud and retire some legacy technology.

Those are the kinds of implications of SVOTC. Those cards can hang there on the Wall for a while.

SVOTC is going to suck resources from all over the organisation if it is allowed to proceed as a normative project. Other projects will become constrained as a result and SVOTC will likely become the primary focus of digital transformation (as it has for many marketing-led companies).

What is the ultimate gain from any given project? Ultimately, the vision needs to be a better outcome for the customer at an acceptable cost to the organisation.

Some companies have now racked up appalling damage to their customer relationships through upselling and cross-selling, particularly those in financial services (who have also faced heavy fines for inappropriate selling). That’s why, from a

flow

perspective, it pays to be cautious and ask what the customer really gains from a project and how value can be delivered quickly.

In many industries, services or products are designed to lack value in order to push the upsell (products like the BMW 1 series and the seating in economy class aircraft are designed to push aspiring people to the next level, the BMW 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7, or business-class tickets, respectively).

Now, we’re not out to change the practices of a whole industry, but we can refresh the vision.

The vision is of a company that continues to add value to the customer’s experience of a product, perhaps through daily changes to its capabilities, which in turn adds value to the customer’s life.

What is different about this perspective is that it refrains from building the business around forcing the upsell. Most car companies, for example, struggle to manage their credit portfolios because their dealerships have effectively sold financial stress to their clients. Businesses are full of costs created by such bad selling strategies.

Ask yourself, “Should my company really spend millions on a brute-force system to sell more to customers that they might find irrelevant or might not really want or can’t afford?”.

Either way, you have to be very careful about the changes you implement and how you communicate those changes. For example, in some parts of the world, there is a distinct and growing wariness of corporate-data usage, to the point where the acronym B2B is being replaced by ME2B to indicate customer control of data in the relationship. As we wander into SVOTC, data issues like that lie in wait.

On the other hand, many of us need to upgrade legacy IT and preferably migrate to the cloud to keep up with new customer demands around scale, scope, and speed. Those facts make data an essential part of the customer-business relationship.

These conflicting thoughts need to find their way onto the Digital Business Wall, where we are trying to redefine the fundamentals of the business. We need many eyes focused on that challenge, so the questions need to be out in the open.

We need to create a wall that gives us an opportunity to explore issues more broadly and to explore other perspectives on customer value. As always, we create the relevant columns. In this case they can be seen on

page 181

: Technologies, Ethnography, Engagement, and Other. We need to complement the Digital Business Wall with more issues. This would include a view of any downstream consequences of SVOTC. The cards don’t have to carry very complex messages or be formally written. The simpler the statements the better, especially when it comes to assessing risk:

Cross-selling, upselling: Which products? Appropriate selling or inappropriate? Risk to reputation?

Cross-selling, upselling: Which products? Appropriate selling or inappropriate? Risk to reputation?

Which existing projects can we choke back without losing value?

Which existing projects can we choke back without losing value?

What talent does a migration to SVOTC need and where will it come from?

What talent does a migration to SVOTC need and where will it come from?

ME2B Movement, reverse data: Is SVOTC the right long-term bet?

ME2B Movement, reverse data: Is SVOTC the right long-term bet?

New platform to consolidate existing data? Cloud is good. Data normalisation and better reference data could contribute.

New platform to consolidate existing data? Cloud is good. Data normalisation and better reference data could contribute.

Big vendor implementation? Risk to company culture?

Big vendor implementation? Risk to company culture?

Cloud migration: opportunities to further microservices’ architecture? Cost savings?

Cloud migration: opportunities to further microservices’ architecture? Cost savings?

Issues like these must become the focal point of discussion. Over the course of the social interaction around them, a simple step forward will emerge, along with a moral position.

Why moral? Well, you are committed to enhancing customer value. At the same time, many businesses wish to maximise revenue at all times. These are not always compatible goals. The right call for the long term is to side with the customer but that position will come under pressure from others in the organisation. Within the constraints of a corporate consensus mechanism, you have to stand up for what the organisation says it believes in. Is it the customer or is it the upsell?

In thinking about these issues, you want to push for new insights into your relationship with customers, and the biggest one is staring you in the face.

How about instead of a single view

of

the customer we think in terms of a single view

for

the customer.

This is in line with the vision of improving the customer’s life at an acceptable cost. It also suggests a course of action, one so simple it eludes many companies:

Let’s talk to customers.

In place of embarking on the implementation of a multimillion-dollar platform, let’s first invite customers in and talk to them.

Introducing the customer to the development dialogue

is actually an imperative, certainly in

flow

, but actually in every business.

“Where I work now,”

say Fin,

“we already host a lot of school parties that come into our offices. We sponsor IT equipment in some of the less wealthy Dublin suburbs and we have the kids in to play around with the apps we are creating. It’s already very instructive for us. But what we really want is a customer lab, where the conversations become more frequent.”

Technologies like big data and AI have made huge differences in the way we do business but they will never be substitutes for the natural human interaction between you and the people who buy your products and services.

Taking the above into consideration, your

Single View FOR the Customer

(SVFTC) project now starts to look like this:

-

Creating a customer venue:

Resource a customer lab and customer dialogue venues in the building, at places where customers gather, or even at a pop up in a nearby town. The cost is minimal and the benefit is that you get feedback on all existing products and pipeline plans. All this will only help creativity. You’ll also get a new voice in the pipeline—the voice of the customer—that will find its way onto the Walls.

-

New market segmentation:

As an interim step, while the new platform is under development, you can draw up a new set of market segments as described in chapter 1

. Those new segments go up on the Wall, and the team comes up with new ways to adapt the flow

and serve more micro-segments.

-

Customer loyalty:

Depending on how much you invest in the dialogue with customers, you become an advocate for them rather than just a sniper out to hit a target. Smart marketers will use this to reach the broader customer community and enhance the sense of unity between company and customer.

-

Resources:

You still have to make decisions on resources but it is worth thinking about what that means in this new context. You want to resource customer interaction, which can be done by choking back a project or two.

-

Vision:

It is in place and enriched. You are more visibly committed to the customer.

Now, you need to consider what will make your SVFTC different from everybody else’s. A new conversation begins. Other companies all around you are doing SVOTC but you have flipped it round.

Cards start to go up on the Wall:

What would this industry look like in 2, 5, and 10 years’ time if... ME2B gets momentum?

What would this industry look like in 2, 5, and 10 years’ time if... ME2B gets momentum?

We really could personalise to markets of one if we embrace ME2B.

We really could personalise to markets of one if we embrace ME2B.

How does AI play into a SVFTC and ME2B?

How does AI play into a SVFTC and ME2B?

How to realise significant gains from a single view for the customer within two years?

How to realise significant gains from a single view for the customer within two years?

Having people who can start these conversations makes for a more exciting workplace. Suddenly, we’re no longer in an old-fashioned organisation dominated by vendor aggression and people who push company policy around like a steam roller, dampening enthusiasm in the process.

Making it work in practice

10. A WALL FOR RECONFIGURING DIGITAL STRATEGY

In this section, we are going to transpose the thinking from the past few pages into a Wall exercise that challenges corporate strategy in a fundamental way.

The underlying principles are the same as those in the last section but we will apply it to one industry—automobiles—to make it more concrete.

In this example, a mandate comes down from the C-Suite to create a SVOTC. The CEO has seen a news report that a competitor is working on one, and he’s been sold heavily at his club by the CEO of a vendor company. Not having a SVOTC currently is affecting his golf swing.

People start to scramble around looking for how SVOTC works. The first reaction is to talk with vendors. But this is a holistic company with a good Wall process and a desire for visual and transparent work processes.

There is a further point to consider. We are in the platform age. Companies that achieve durable competitive success will tend to have a platform strategy. Think Facebook, a platform for sharing personal content and (supposedly) contextual advertising. Apple is a platform for apps, content, and mobile-phone utility. Alibaba is a platform for global trade.

In the automotive industry, there is a realistic expectation that cars are becoming a kind of platform. This will only increase once autonomous vehicles are commonplace. For hours a day, auto companies will hold people captive to screens on the dashboard and/or the smartphone. Undoubtedly, there will be scope to grow a content and developer ecosystem but in competition with Google, Netflix, Facebook, etc.

Right now, however, most automakers have poor platform strategies. Their profitable revenue streams do not lie in car sales. Rather, the cash cow is after-sales service and extra parts. And to capitalise on this, they need extremely good customer retention. Retention issues are critical to profitability.

As long as a car’s service warranty is in place the dealer can incentivise loyalty: if customers do not have their cars serviced at a dealer’s garage, the warranty is void. After the service warranty expires, however, customer loyalty drops off a cliff as people go in search of cheaper servicing or no servicing at all.

This is the backdrop for the CEO’s call for a SVOTC. The CEO’s strategic position is that he needs to transform to a platform company but in the meantime he has to sustain and hopefully increase his parts’ revenues. He wants to know exactly how he can leverage the behavioural profiles that SVOTC offers in order to incentivise people back into the dealerships after the end of a service warranty.

Here’s how we might develop the initial Wall to address the issue of customer retention and platform strategy.

In a non-

flow

context, the work would be broken down as per the column on the left. There would be some feasibility work around the technology, and it would include data discovery (e.g., What data do we actually collect?) as well as what that means in terms of having to normalise data, construct reference data and master data management around it. And there would have to be some workflow discovery around how the new project will change work processes.

Each of these is a substantial project in its own right and needs the detail articulated. And each fits into different strategic flows such as the one that goes into and out of the long term goal of digital transformation.

The problem that this car company faces is not actually SVOTC or its technical requirements, though it can quickly appear as though the technical challenges are an end in themselves.

The problem for automakers is customer retention. That’s what we really need to address. So it pays to step back and remind ourselves of this. What problem are we really addressing?

We have sketched in some time horizons on the Wall, too. You can see that most elements of a SVOTC project are in excess of twelve months, and they are XL in size. A far-sighted CTO will see the dangers of her company getting swamped by this project. She will look to other tools and smaller steps than these, without losing sight of the fact that some form of big data or AI project is inevitable. It’s a way to go but to do it right now, straight out of the blocks, is going to squeeze out too many other options.

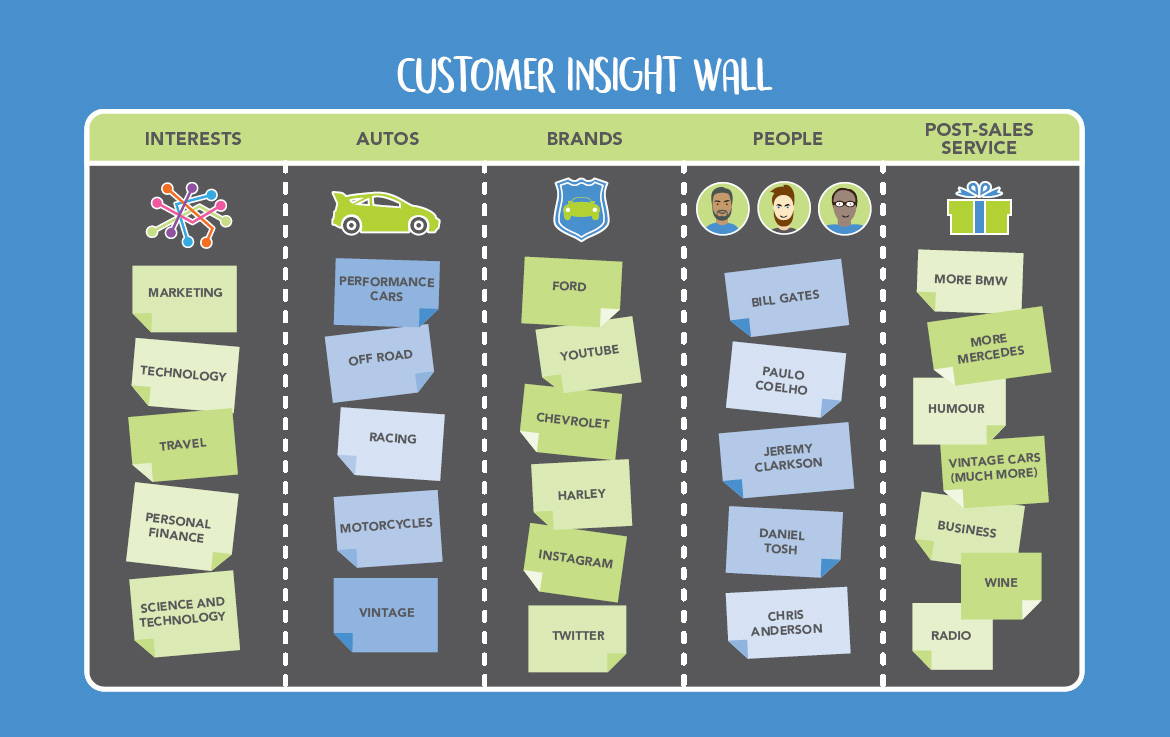

In posting the problem to the Wall, the CTO has invited a holistic view of how customer insights can be acquired, with particular emphasis on this being an exercise to further our knowledge of the customer rather than just being about a technical implementation.

One column, headed Ethnography, poses the question: Can we study customers in some shorter time horizon than the SVOTC platform to create new data about their needs?

The next is Engagement. Are there customer engagement tools that will help us go further along the path?

And finally, the is a column called Other. This signals a desire to expose other useful tools to the team.

An ethnographic project could be quick—less than three months. The same applies to Engagement.

These kinds of projects are also easy to commission. The CTO asks for a staff member with a background in sociology to spend time in dealerships, and she sets up a small welcome room in a town pop-up shop to have her people just talk to customers and engage them with the company’s challenges.

Meanwhile, she also decides to commission a proof of concept (PoC) of a SVOTC solution.

The illustration on the previous page shows the results of these steps with the possibility of a T-shirt size being allocated to the issues identified.

While the PoC is being figured out, some new thoughts have gone up in the “Other” column, and the ethnography and engagement teams report back.

From the ethnography we find that:

-

In most cases, customer issues are LARGE.

-

There are serious gender issues in many dealerships, particularly when women arrive to hand over their car keys and then later when picking up a serviced car. The environment of the garage is just too male oriented and outdated. Beyond the garage, the sales personnel tend to be men and the reception is managed by a woman. It looks like 1980. As well, it makes no concession to the fact that some of the customers have children with them and need to get them to school, kindergarten, etc.

-

The dealer lot is empty for most of the time. Apart from Saturdays, the cars stand like gleaming monuments of a past age, and the only people looking at them are the sales staff.

-

Selling is aggressive and subtly gladiatorial, with an implicit emphasis on shaming customers into the upsell (Can’t afford it buddy, huh?

). This makes customers visibly uncomfortable and risks straining the company’s credit portfolio as people are persuaded to buy cars they cannot afford.

-

There is inflexible scheduling for servicing cars, meaning many customers need to arrange a lift from the garage to the workplace (having already taken an hour off work for the drop-off). Or they have to walk to work or push a pram down the forecourt to get home. Same at pick up time. No wonder they don’t want to come back.

-

The initial engagement research reinforces that conclusion. Lifts, or a lack of them, are a major reason why people don’t go to the dealership service.

-

A school visit shows that next to no girls envision themselves as mechanics, though they are interested in the allure of cars.

-

The “Other” column reveals a major drift against the use of customer data for sales, inspired by companies like SNAP and their disappearing photo service.

-

In addition, there is more regulatory pressure coming on data usage that may compromise vendor solutions.

-

The new customer segmentation tells you that a significant portion of the customer base is actually quite interested in cycling and the outdoors. But this is only one segment among many that give clues as to how a platform could help them more. (Sell bike parts? Partner with other mobility solutions? Provide AR-mapping apps for customer outings?) Ironically, the fans of the car company are different from those of the services and parts division. Servicing attracts a much more aspirational customer segment (see

page 185

) and people with a deeper interest in cars.

-

Finally, this new ME2B movement promises to shape data storage in ways customers can control. Facebook has backed it and Apple has been making similar noises. It is going to have an impact on corporate data use.

All this information is in before the SVOTC project enters its PoC. What it tells you is that:

The technical solution is long term, complex, and will be subject to pressures that have not been anticipated by vendors of the SVOTC solution. The lack of opportunity for short-term value creation poses the risk of a big project eating up resources and creating delivery risk.

The technical solution is long term, complex, and will be subject to pressures that have not been anticipated by vendors of the SVOTC solution. The lack of opportunity for short-term value creation poses the risk of a big project eating up resources and creating delivery risk.

There is a strong need to anticipate pivot points in the tech project, which needs to sit within a single view

for

the customer. Nonetheless, the PoC will undoubtedly show that the SVOTC project should go ahead—tech vendors are very persuasive.

There is a strong need to anticipate pivot points in the tech project, which needs to sit within a single view

for

the customer. Nonetheless, the PoC will undoubtedly show that the SVOTC project should go ahead—tech vendors are very persuasive.

A program of customer retention can be launched alongside the SVOTC project. The SVOTC needs to be within a flow of information about changing attitudes and regulatory requirements.

A program of customer retention can be launched alongside the SVOTC project. The SVOTC needs to be within a flow of information about changing attitudes and regulatory requirements.

The platform strategy should seek better ways of using real estate. It should find better ways to schedule customer appointments and assist with onward journeys; have an outreach element to sell cars in different locations; consider gender balance (offering female mechanic apprenticeships); look at third-party assets that can pass through the dealership by taking the customer segmentation to heart; probably migrating them to multimodal opportunities at dealerships; create marketing programmes that convert the petrolhead customer to somebody with an appreciation of the broader culture of the auto and its future.

The platform strategy should seek better ways of using real estate. It should find better ways to schedule customer appointments and assist with onward journeys; have an outreach element to sell cars in different locations; consider gender balance (offering female mechanic apprenticeships); look at third-party assets that can pass through the dealership by taking the customer segmentation to heart; probably migrating them to multimodal opportunities at dealerships; create marketing programmes that convert the petrolhead customer to somebody with an appreciation of the broader culture of the auto and its future.

These aspects of customer knowledge need to inform the overall project. The dream of having a data source that can flick a switch in customers’ heads and make them more likely to buy or return for services is just that—a dream.

The SVFTC suggests a much more holistic solution to the problem. The lessons can now be framed as SVFTC projects and be streamed into the

flow

, starting with evaluation.

The importance of

flow

in keeping delivery of value going and resisting the drift that big projects create.

The importance of

flow

in keeping delivery of value going and resisting the drift that big projects create.

The importance of

flow

in keeping delivery of value going and resisting the drift that big projects create.

The importance of

flow

in keeping delivery of value going and resisting the drift that big projects create.

The nature of social interaction as a complex learning system where everyone has a voice.

The nature of social interaction as a complex learning system where everyone has a voice.

Customer front and centre. Going digital.

Customer front and centre. Going digital.

Offence: delivering upside through new market entry; increased share of wallet.

Offence: delivering upside through new market entry; increased share of wallet.

Defence: cost focus / rationalisation.

Defence: cost focus / rationalisation.

Prioritising innovation and change

Prioritising innovation and change

A data-driven method of cross-selling or upselling to customers.

A data-driven method of cross-selling or upselling to customers.

Potentially a lower cost of sale and therefore a higher margin.

Potentially a lower cost of sale and therefore a higher margin.

An opportunity to segment the market in new ways through data.

An opportunity to segment the market in new ways through data.

The potential for customer loyalty but also the potential to create problems around privacy.

The potential for customer loyalty but also the potential to create problems around privacy.

Potentially transitioning away from advertising and mass marketing to what’s becoming known as “the market of one” (i.e., getting enough data to sell at scale to each individual).

Potentially transitioning away from advertising and mass marketing to what’s becoming known as “the market of one” (i.e., getting enough data to sell at scale to each individual).

Potentially buying a vendor platform or solution, even if we may not need one. Creating an imbalance in departmental budgets.

Potentially buying a vendor platform or solution, even if we may not need one. Creating an imbalance in departmental budgets.

Probably an opportunity to extend data-capture to the customer call centres, which will anyway be buying bots to automate customer transactions and build new data sources.

Probably an opportunity to extend data-capture to the customer call centres, which will anyway be buying bots to automate customer transactions and build new data sources.

An opportunity to move infrastructure to the cloud and retire some legacy technology.

An opportunity to move infrastructure to the cloud and retire some legacy technology.

Cross-selling, upselling: Which products? Appropriate selling or inappropriate? Risk to reputation?

Cross-selling, upselling: Which products? Appropriate selling or inappropriate? Risk to reputation?

Which existing projects can we choke back without losing value?

Which existing projects can we choke back without losing value?

What talent does a migration to SVOTC need and where will it come from?

What talent does a migration to SVOTC need and where will it come from?

ME2B Movement, reverse data: Is SVOTC the right long-term bet?

ME2B Movement, reverse data: Is SVOTC the right long-term bet?

New platform to consolidate existing data? Cloud is good. Data normalisation and better reference data could contribute.

New platform to consolidate existing data? Cloud is good. Data normalisation and better reference data could contribute.

Big vendor implementation? Risk to company culture?

Big vendor implementation? Risk to company culture?

Cloud migration: opportunities to further microservices’ architecture? Cost savings?

Cloud migration: opportunities to further microservices’ architecture? Cost savings?

What would this industry look like in 2, 5, and 10 years’ time if... ME2B gets momentum?

What would this industry look like in 2, 5, and 10 years’ time if... ME2B gets momentum?

We really could personalise to markets of one if we embrace ME2B.

We really could personalise to markets of one if we embrace ME2B.

How does AI play into a SVFTC and ME2B?

How does AI play into a SVFTC and ME2B?

How to realise significant gains from a single view for the customer within two years?

How to realise significant gains from a single view for the customer within two years?

The technical solution is long term, complex, and will be subject to pressures that have not been anticipated by vendors of the SVOTC solution. The lack of opportunity for short-term value creation poses the risk of a big project eating up resources and creating delivery risk.

The technical solution is long term, complex, and will be subject to pressures that have not been anticipated by vendors of the SVOTC solution. The lack of opportunity for short-term value creation poses the risk of a big project eating up resources and creating delivery risk.

There is a strong need to anticipate pivot points in the tech project, which needs to sit within a single view

for

the customer. Nonetheless, the PoC will undoubtedly show that the SVOTC project should go ahead—tech vendors are very persuasive.

There is a strong need to anticipate pivot points in the tech project, which needs to sit within a single view

for

the customer. Nonetheless, the PoC will undoubtedly show that the SVOTC project should go ahead—tech vendors are very persuasive.

A program of customer retention can be launched alongside the SVOTC project. The SVOTC needs to be within a flow of information about changing attitudes and regulatory requirements.

A program of customer retention can be launched alongside the SVOTC project. The SVOTC needs to be within a flow of information about changing attitudes and regulatory requirements.

The platform strategy should seek better ways of using real estate. It should find better ways to schedule customer appointments and assist with onward journeys; have an outreach element to sell cars in different locations; consider gender balance (offering female mechanic apprenticeships); look at third-party assets that can pass through the dealership by taking the customer segmentation to heart; probably migrating them to multimodal opportunities at dealerships; create marketing programmes that convert the petrolhead customer to somebody with an appreciation of the broader culture of the auto and its future.

The platform strategy should seek better ways of using real estate. It should find better ways to schedule customer appointments and assist with onward journeys; have an outreach element to sell cars in different locations; consider gender balance (offering female mechanic apprenticeships); look at third-party assets that can pass through the dealership by taking the customer segmentation to heart; probably migrating them to multimodal opportunities at dealerships; create marketing programmes that convert the petrolhead customer to somebody with an appreciation of the broader culture of the auto and its future.