THE ACADEMY

We began this book with a small number of simple hypotheses:

“Good decisions stem from good social interaction.”

“Good decisions stem from good social interaction.”

“Learning arises from social interaction more than it does from the transfer of information from one person to another or through creativity.”

“Learning arises from social interaction more than it does from the transfer of information from one person to another or through creativity.”

“Belief is the single biggest responsibility of a leader.”

“Belief is the single biggest responsibility of a leader.”

“Nurturing belief in others is a burden that few leaders accept.”

“Nurturing belief in others is a burden that few leaders accept.”

We have also pointed to research that shows how

“share of conversation”

among members of teams is a critical factor in creating good work.

What all of these factors have in common is that they are intensely personal. And therein lies the rub for conventional management and leadership techniques. There is no hierarchy, performance review, or silo where people can hide from the power of relationships.

Instead, the organisation depends on leaders who know how to shape conversations and those who are able to sustain themselves under conditions of uncertainty.

No change program will deliver these assets. If you want them, you have to create the learning environment.

In this final chapter, we will address learning head on. As mentioned earlier, learning has four elements:

Creativity, Learning Transfer, Belief

and

Social Interaction

We will talk about learning in the context of what we call The Academy Wall, or just The Academy. Yes, the term is a little portentous but it captures the range of learning activities that good social interaction facilitates. An Academy sounds about right, at least if we refuse to take ourselves too seriously.

To recap on learning:

This is the long-term reinvention of processes. It is far too easy to see creativity in short-term gains like a new app, feature or service. But when you look across industries, creativity is all about how organisations reinvent themselves over lengthy periods of time. It is an unimaginably complex process. The best example remains Apple, who from 2000 to 2012 put right a lot of its past failures and transformed in a variety of ways. That process also involves individuals in reimagining their own roles and skills.

In organisational terms, this is the meaning of creativity, the capacity to take the whole organisation through successive major transformations in order to reinvent it. And in these companies, management has the stomach for big bets backed by big belief.

Companies try, over and over, to transfer information by passing knowledge from one person to another: from a conference speaker to an audience, from a workshop leader to a team, from a manager to a newbie. This has proven difficult for both sides because people work within rules laid down by big software systems. It has become problematic now that we are liberating ourselves from Big Software.

Many of the barriers to learning exist because people have deep, core frameworks that inform their day-today activities. It has taken parenting, schooling, and community life to create those frameworks, and they are not really fungible. Psychologist Stellan Ohlsson tells us we need to frame new experiences within people’s existing core frameworks if we are to succeed in changing their behaviour.

How that might happen, efficiently, is really a matter of guesswork or intuition. Dan Pontefract, who leads transformation at Telus, Canada’s largest mobile network, believes there is a key paradox in the transition from childhood and school to work.

For the most part, we are brought up to believe we must think for ourselves. In principle, the journey from adolescence to adulthood is a transition away from dependencies (on parents, schools, etc.) to an independent mindset. But the organisations we then go to work for deny us access to this hard-earned asset. At work, for the past fifty years, there has been little scope for independent minds.

There is an element of inevitability about that. Organisations need loyalty and can’t find space for a great deal of maverick behaviour. But how they go about securing that loyalty and conformity strikes against the instincts of many free-thinking people: the insistence on alignment with bad plans, processes that bore people into depressive moods, and the political contest for advancement.

We said earlier that you need to work with employee’s belief in the right to think freely. In an era where people spend more time concerned with work and less with their personal lives, they have the right to believe leaders will care about this.

Finally, we have sung the virtues of good interaction and setting the scene for it, visually. The evidence shows that when more people in a team get a chance to speak, project outcomes are better. Full stop. And the evidence shows that visible lessons are more easy to grasp.

But there is so much more to the idea of social interaction than that.

The way we think, form opinions, and assimilate information today is different from what it was two decades ago. We have very little time, opportunity, or inclination for reflection. And yet we have to think, reflect, and absorb, from a constant and abundant

flow

of information.

The new philosophy of how we think, of cognition, more or less accepts that we function through what can be termed “neural, bodily, and environmental processes.”

11

Pierre Levy has raised the possibility that the most fundamental change is not just in the environmental tools that help us think (from pen and paper to computer and internet) but in the enormous flow of information that we must somehow shape to our advantage.

It stands to reason that shaping the flow has to be done through social interaction and visualisation. Why?

Just as we need a pen and paper to do some kinds of maths, and humble Scrabble pieces to come up with words in a game, we need some form of external tooling to help us think about information flows.

The critical information flows for work can be:

New techniques from vendors, open source, meetups, etc.

New techniques from vendors, open source, meetups, etc.

The experiences of others in our milieu.

The experiences of others in our milieu.

Third-party data on the resegmentation of markets or changes in customer needs.

Third-party data on the resegmentation of markets or changes in customer needs.

Internal data from data warehouses.

Internal data from data warehouses.

Trial and error.

Trial and error.

System-performance metrics. Personal capabilities.

System-performance metrics. Personal capabilities.

Emotional entanglements or disturbances in people’s lives.

Emotional entanglements or disturbances in people’s lives.

Resource availability (even to the simple degree of knowing who is on sick leave or when vacations arise).

Resource availability (even to the simple degree of knowing who is on sick leave or when vacations arise).

System redesigns.

System redesigns.

Social interaction and the right visual representations of knowledge allow many eyes to view and review the knowledge flow. They allow people to see the overall Script of a company’s progress and to collaborate in real-time with their colleagues. Collective intelligence becomes social intelligence, which means the group is making the many additional decisions firms now require.

But all of this needs multiple forms of support. To date, we have looked at visualisations. The idea of The Academy means more than that. Primarily, the additional factor lies in finding the right story formats for learning.

The Academy has the same physical presence as everything else we have discussed: a Wall and people who talk. It includes:

First of all, no tools invalidate the idea that social interaction is the primary channel for all learning. Rather, tools are ways to help inform and shape the conversations that take place.

The learning model is a mix of interaction and additional targeted activities. It includes set times during the week to focus on learning, a kind of academy time where strands of new experience can be documented on the Learning Wall.

Academy time, which should be treated as an event, should be happening once a week, even if just for a half hour.

This idea of meeting to learn is sometimes referred to as a “retrospective” in Agile. However, problems can arise with retrospectives:

They are always backwards looking.

They are always backwards looking.

They tend to point the finger at people and can be uncomfortable, scapegoating experiences rather than valued didactic ones.

They tend to point the finger at people and can be uncomfortable, scapegoating experiences rather than valued didactic ones.

They do not draw in external experiences such as new learning from outside the organisation.

They do not draw in external experiences such as new learning from outside the organisation.

They happen at the end of projects, when the problems have already exacted a price.

They happen at the end of projects, when the problems have already exacted a price.

The Academy is a more comprehensive learning experience and is meant to challenge the place of retrospectives. It is a better way to learn.

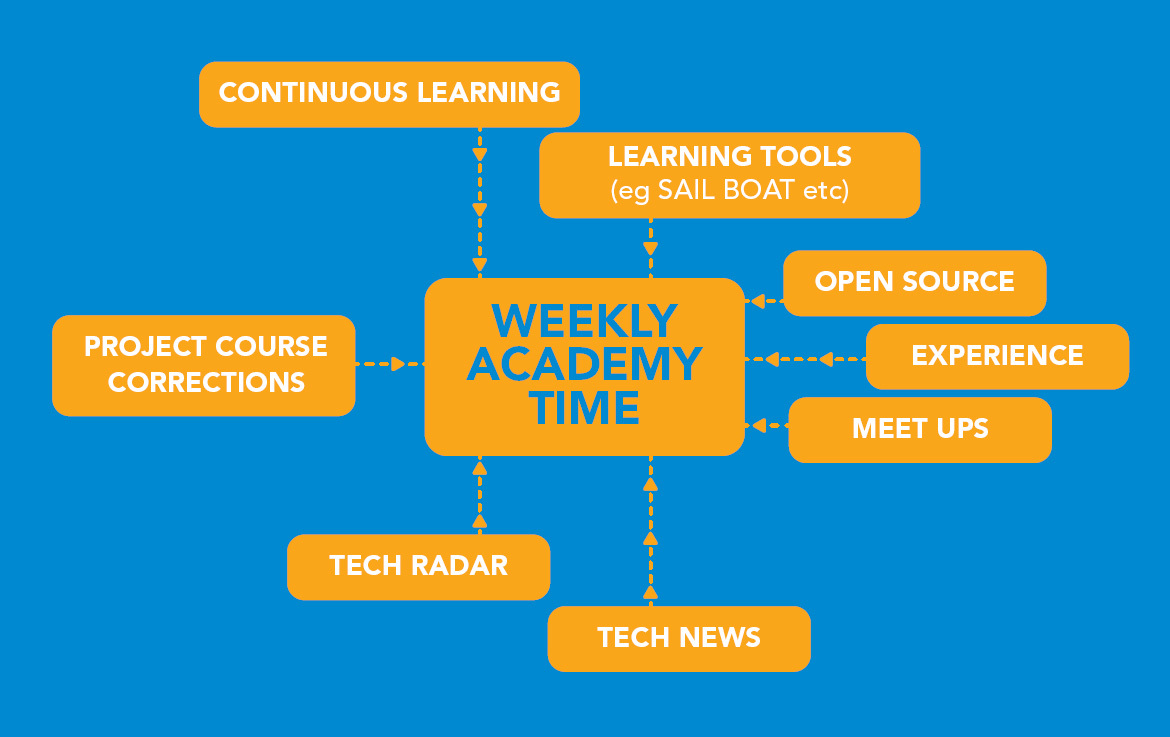

At the top of the diagram on the next page, you can see some of the tools we will discuss in this chapter.

On the right, external experiences, such as engagement with the open-source community or meetups, conferences, and jams, are brought into the learning event (they can be posted to the Learning Wall so that people get a preview).

At the bottom of the diagram, you see more formal news sources. For example, if you work with the consultancy ThoughtWorks, you will have access to their Technology Radar. If not, you will be reading websites like TheNextWeb or following sites like Linux Foundation.

On the left, there are project-course-correction documents or experiences. What has been learned from other parts of the project or other projects in the company this week?

These can be brought in as topical reminders that good practices are being built all the time and that some problems have already been solved elsewhere in the team.

The Learning Wall is the repository for every new piece of information that people want to share. Like all Walls, it is a space to pin up short summaries, not essays. Organise the Wall in your own way but perhaps start with the diagram above. Those four elements should suffice.

Take a card and summarise, in a sentence, what was learned from tackling a new problem, deciding to abandon a piece of work, taking on a new tool, or accelerating a novel solution. What is new in the Customer Lab or Wall? What’s being learned from meetups? Just one card, one sentence.

You need access to information on new techniques, tools, platforms, and frameworks. But having access to information is easy. The hard part is using it as a key asset among teams. As far as possible, you want to understand people’s experiences with new tools and techniques, and you need to figure out what to do with this information.

You may think this Tech Radar is irrelevant to the CFO or CMO. Yet most CFOs, in even smallish companies, now deal with multiple exotic currencies and need to find technologies that give them end-to-end control of cash. Most marketers are inundated with new ways to succeed on Pinterest, Instagram, Facebook, Google Plus, LinkedIn, SnapChat, and so on. They need a Tech Radar, and they need collective intelligence to shape technical information, just as much as the CIO and CTO do.

You can divide the task of evaluating tools into

Assess, Trial, Hold

and

Adopt

.

Those four elements are valid also for existing techniques. There should be a regular attempt at assessing the new tools used by staff, especially in shadow IT projects, trials of new tools, decisions to hold or discard existing tools, and decisions to adopt new ones.

If you don’t have access to a third party radar, create your own. Keep in mind, though, that there is far too much out there for your department to track.

Tools like the Tech Radar are important for more than just giving valuable new information. Most developers will constantly be trying out new tools anyway. Marketers play with social media in their personal lives and come to work hyping up the next influencer, tool, or persona-building technique.

The problem is that staff may be adopting these ideas even if the tools are not the best way to get work done. The Cool Wall is meant to address that.

The Cool Wall, you might remember us saying earlier (in

Chapter 6

), is the place where people can post their one liners about new techniques. It might sound frivolous to call it a one liner but we live in the world of Twitter, where @POTUS runs the world’s largest economy through tweets. Being brief is powerful

We take those one-line suggestions and make them the topic for a serious Friday rundown on how we could do better. In Fin’s case, he gets his teams to vote on which ideas need more elaboration and discussion before being adopted. That could be cool code for integrating video into a web page or great results in customer segmentation with StatSocial analysis, for example.

You should make a stipulation about inclusion. People are encouraged to try out new ways to work but they need to demonstrate the value or post the lack of value in public.

The Cool Wall needs these four categories:

This is a way to get ideas into the more formal

Assess, Trial, Hold, Adopt

process that we mentioned above.

In one of Fin’s departments, Friday afternoons are for storytelling. They are particularly reserved for stories about experiments and tests that people are doing (see The Cool Wall above). These are not retrospectives. They are perspectives on the future, on what can change for the better.

Storytelling involves both the business side and the IT side of the house. The objective is to have four or five people do five-minute pitches on what they are learning. These pitches could be about customers, tools, or solutions. The room should be full. We’re talking 100 people or more (or for a smaller company, everybody) before they go off for the weekend. It is not a demo (as in Agile). It is a debate, an intellectual setting where the fit between how we understand customers and how we understand techniques gets aired and tested in public. These are also hypotheses about bringing the future into view.

In Blue Ocean thinking, based on the book

Blue Ocean Strategy

, about seeking out uncontested space in markets, there is a very simple approach to work. We adopt this approach to weekly review meetings.

It starts with what were we doing that we decided to kill off (because it didn’t work). What new things are we doing that we are happy to continue with? Now that we have cleared some clutter from Stop Doing, what new things do we have the bandwidth to get started on?

The idea of the weekly Academy time is to focus on projects, their problems, and the solutions we are trying out. If you have the Cool Wall, Tech Radar and The Friday Story nailed down (or rather, tacked up on the Learning Wall), you are in a position to make judgments about what to stop, continue, or start.

The objective of the Blue Ocean segment of the Learning Wall is to identify a manageable amount of learning by bringing together the collective intelligence of the group.

Ask people to vote on the top three items in each of these columns (Stop, Continue, Start). Those columns, remember, consist of things people in your teams have been trying out. You are not seeking to embarrass anyone here. You are bringing a collective voice to decide what is and is not valid.

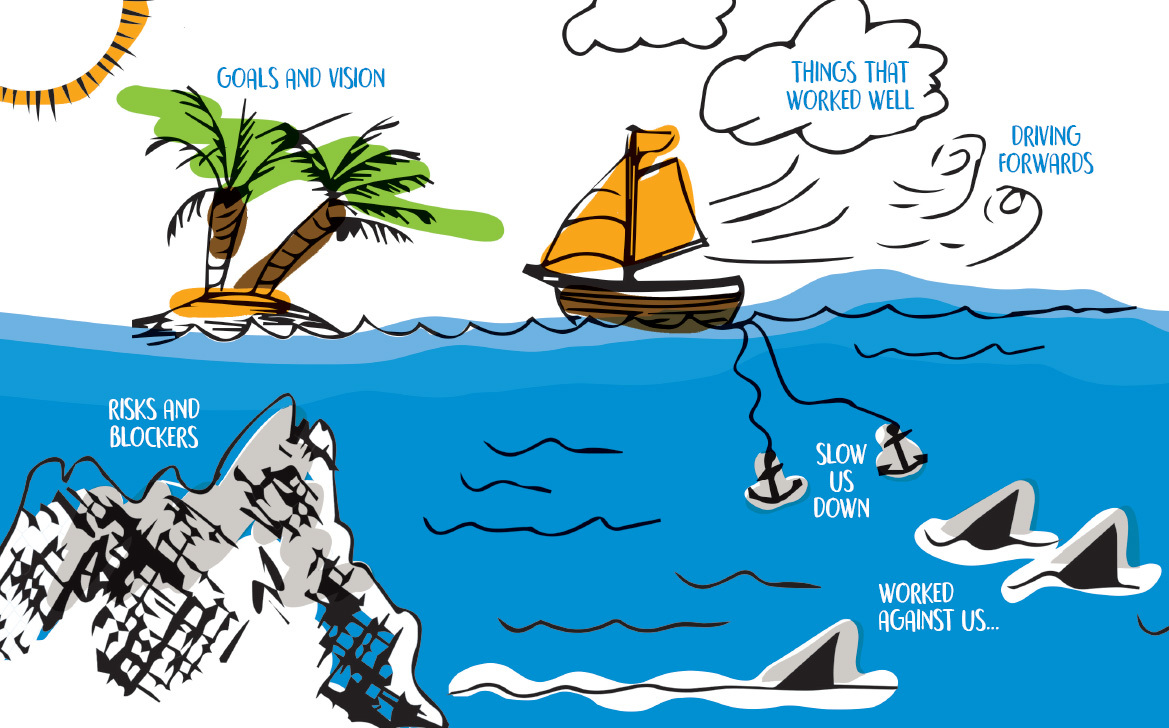

Sail Boat is a friendly retrospective technique and a much kinder way to learn. Here’s how to do Sail Boat.

You draw one big picture which includes a

Sail Boat

, an

Island, Wind in the Sails, Iceberg, Anchors, Clouds

and

Sharks!

The Island represents the teams goals and vision for the project and what we need to do in order to get a project back on course.

The Island represents the teams goals and vision for the project and what we need to do in order to get a project back on course.

The Wind in the Sails are the things that worked well and drove us forward.

The Wind in the Sails are the things that worked well and drove us forward.

The Iceberg represents the risks and blockers that we encountered, which stopped us from achieving the goals and vision.

The Iceberg represents the risks and blockers that we encountered, which stopped us from achieving the goals and vision.

The Anchors on the Sail Boat represent everything that slowed us down.

The Anchors on the Sail Boat represent everything that slowed us down.

The Clouds represent everything that worked well and the things that could help us in the future.

The Clouds represent everything that worked well and the things that could help us in the future.

And finally the Sharks. These are things that worked against us. Perhaps an executive who kept stealing team members - feel free to improvise.

And finally the Sharks. These are things that worked against us. Perhaps an executive who kept stealing team members - feel free to improvise.

Fin says,

“I attended a retro workshop recently and the facilitator used pirates to depict the audit team! A tad unfair, I hear you say… but the auditors loved it!

Anyway, everyone in the session takes it in turns to write on Post-it notes the items that they believe fit into each category and then stick them on the picture. While we prefer one big picture it can get out of hand if there are too many people in the mix! If the group of people in the retro is too large, then one can use individual flipcharts with each topic on one page. This does make it easier if there are lots of Post-it notes.

The facilitator looks for common points and removes duplicates. Multiple ‘common’ Post-it’s are grouped together for a detailed discussion and very soon the key issues, blockers and things that propelled the team, come to the fore.

Some teams prefer to document the retro for wider distribution. It’s quite easy to use PowerPoint or KeyNote to put one topic on each slide in order to pull out the key learnings.

But the reason that we prefer the one picture is that it can be placed on a wall near the team and serve not only as a reminder but also a visual representation for everyone in the company to see, use and learn.

And finally, do make sure that you re-iterate the Retrospective Prime Directive before any type of reflective process. Which is:

“Regardless of what we discover, we understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could, given what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand”.

Write it on a flip chart, hang it on the wall, use it as a positive affirmation of the process and you won’t go wrong.”

Before going on to what could also be called lay-planning tools, we want to emphasise once more that the two metrics in constant use are:

-

Value for the customer:

What are we providing for them and how closely can that be visualised and measured? Is the feature, function, or message important enough to impact satisfaction or uptake? The only way to find out is to talk with customers and deliver options they can try out.

-

Cycle time:

By cycle time we mean the time it takes to complete any single work package. If cycle time is decreasing, all is golden, or should be. It means you are faster at creating value. If it is increasing, then something is wrong. The source of the problem could be in work design. It could be in areas like sick leave or holidays. Or it could be that a team member is not capable of fulfilling the tasks assigned. But cycle time tells you it is one of these. If cycle time increases go unchecked, you are storing up resource issues.

Finally, we have emphasised throughout this book that planning happens through interaction.

That’s not to say there are no formal techniques. Facebook, for example, uses a simple tool called Horizon Planning. There are plenty of ideas about the general concept of horizon planning but Facebook’s is admirably simple and therefore usable.

Left to their own devices, leaders typically create impossible plans. They don’t know enough about what’s possible and what’s changing, so they cannot plan ahead realistically. It is risible to fake omniscience in today’s information flow. If leaders pretend they know everything, the folks around them are probably not going to follow.

So what are the good alternatives to yesterday’s big plans? Some kind of conversational process is needed. It is simply about making a call on a three-, six-, nine-, or twelve-month horizon. That timescale is about right if the priority is to get things done without falling over and looking stupid.

Because leaders are typically out of touch, they need to socialise the question of what can be done on these timescales.

Take a look back at the Executive Portfolio Wall, examining the tasks that should deliver the C-Suite’s objectives. Which can credibly be done within three months?

It is surprising how much the answer to that will vary across a team of people. But pose it at a planning standup. There will be folks there who know exactly how to crack the problem you have articulated and will tell you it fits squarely within a three-month timescale. Contrariwise, you will be posing three-month tasks that some people will tell you need pushing out to six or nine months.

You can do this planning exercise on a Wall too. We haven’t tried it yet but why not go for it. Introduce a Horizon Wall.

Making it work in practice

11. THE RECIPE FOR HAPPY SAILING

In the City of Lyon, France, they have a dish called Fromage du Tête. It must be some kind of cheese, right? Well, sadly it is a vegetarian’s worst nightmare. It consists of offal from a pig’s head, all made up into what looks like a reasonably appetising pâté.

We mention Fromage du Tête simply to point out that things (events, processes, etc.) are often not what they seem.

People in organisations tend to want documentation, plans, proofs. What these really amount to is a demand for evidence that something is going to work. Or, to put it even more simply, evidence that the future is good and will arrive on time.

Asking for evidence is perfectly natural and a good demand to make. It may seem that what we have said to date in this book is a counter to that very good notion. It isn’t. What we are saying, though, is that much of the documentation, plans, and proofs that get passed around organisations are often attempts to cover up for a lack of evidence or a bad plan. They have little practical value. They are Fromage du Tête.

Flow

is real, shouldered by people who will care more about you, your leadership, and your products if you follow its principles. We know many readers will be thinking, “Heck, you are so right. I never thought of it that way (:-))”.

Seriously though, the big issue you might face is how to get going with

flow

. Where do you start?

Earlier on in the book, we pointed out that customer segmentation, understanding the market in new ways, and bringing customers inside the building are all good places to start. But so too is The Executive Portfolio Wall.

The first principle of

flow

, before making any decisions from good social interaction, is to taste before you serve. Try things out.

Here once again are your main ingredients:

The Customer Wall

The Customer Wall

The Executive Wall

The Executive Wall

The Culture Wall

The Culture Wall

The Digital Business Wall

The Digital Business Wall

The Executive Portfolio Wall

The Executive Portfolio Wall

The Evaluation Wall

The Evaluation Wall

The Project Wall

The Project Wall

The Team Kanban Wall

The Team Kanban Wall

The Risks and Issues Wall

The Risks and Issues Wall

Fun Walls and Job Walls Obeya

Fun Walls and Job Walls Obeya

The Academy or Learning Wall

The Academy or Learning Wall

Cool Walls, Sail Boats, Blue Ocean, Friday Stories

Cool Walls, Sail Boats, Blue Ocean, Friday Stories

The Mosaic Metaphor

The Mosaic Metaphor

The Horizons Wall

The Horizons Wall

Really Simple Metrics

Really Simple Metrics

Very Subtle Gamification

Very Subtle Gamification

You cannot cook all this at once without making a mess. So take your pick.

The whole point of

flow

is to create your own. Our Walls are there to be adapted and augmented, and you and your colleagues need to assess, trial, and adopt (or not adopt). Typically, it takes about two years to create really good

flow

. So what will be your first step?

Taking up The Customer Wall is a good way to start, because it appears unthreatening. You may hit a problem, though, for that very reason. What your Customers want may not fit with the CEO’s top priorities. You have good information there but your diplomacy skills need to be well honed if you are to force customer needs further into the enterprise.

You could start with The Executive Portfolio Wall. This has special value if the company faces resource issues, since that Wall will free up money. If you are ready with some experience of the Customer Wall before tearing down the CEO’s horse pictures or art collection for the Executive Portfolio Wall, that’s a good place to be.

But you may also want to start with The Jobs Wall or Fun Walls, because maybe you don’t quite believe what we are saying.

Maybe you don’t yet have full confidence in your people. And if you do not, then they are not going to have confidence in you. That relationship is absolutely a two-way mirror.

Get everyone together for Friday Story and ask folks what they think. Chances are, this is your best possible start point, with your people guiding you to a better plan, a more realistic schedule, and a better way to lead.

“The Extended Mind” Andy Clark and David Chalmers

“Good decisions stem from good social interaction.”

“Good decisions stem from good social interaction.”

“Good decisions stem from good social interaction.”

“Good decisions stem from good social interaction.”

“Learning arises from social interaction more than it does from the transfer of information from one person to another or through creativity.”

“Learning arises from social interaction more than it does from the transfer of information from one person to another or through creativity.”

“Belief is the single biggest responsibility of a leader.”

“Belief is the single biggest responsibility of a leader.”

“Nurturing belief in others is a burden that few leaders accept.”

“Nurturing belief in others is a burden that few leaders accept.”

New techniques from vendors, open source, meetups, etc.

New techniques from vendors, open source, meetups, etc.

The experiences of others in our milieu.

The experiences of others in our milieu.

Third-party data on the resegmentation of markets or changes in customer needs.

Third-party data on the resegmentation of markets or changes in customer needs.

Internal data from data warehouses.

Internal data from data warehouses.

Trial and error.

Trial and error.

System-performance metrics. Personal capabilities.

System-performance metrics. Personal capabilities.

Emotional entanglements or disturbances in people’s lives.

Emotional entanglements or disturbances in people’s lives.

Resource availability (even to the simple degree of knowing who is on sick leave or when vacations arise).

Resource availability (even to the simple degree of knowing who is on sick leave or when vacations arise).

System redesigns.

System redesigns.

They are always backwards looking.

They are always backwards looking.

They tend to point the finger at people and can be uncomfortable, scapegoating experiences rather than valued didactic ones.

They tend to point the finger at people and can be uncomfortable, scapegoating experiences rather than valued didactic ones.

They do not draw in external experiences such as new learning from outside the organisation.

They do not draw in external experiences such as new learning from outside the organisation.

They happen at the end of projects, when the problems have already exacted a price.

They happen at the end of projects, when the problems have already exacted a price.

The Island represents the teams goals and vision for the project and what we need to do in order to get a project back on course.

The Island represents the teams goals and vision for the project and what we need to do in order to get a project back on course.

The Wind in the Sails are the things that worked well and drove us forward.

The Wind in the Sails are the things that worked well and drove us forward.

The Iceberg represents the risks and blockers that we encountered, which stopped us from achieving the goals and vision.

The Iceberg represents the risks and blockers that we encountered, which stopped us from achieving the goals and vision.

The Anchors on the Sail Boat represent everything that slowed us down.

The Anchors on the Sail Boat represent everything that slowed us down.

The Clouds represent everything that worked well and the things that could help us in the future.

The Clouds represent everything that worked well and the things that could help us in the future.

And finally the Sharks. These are things that worked against us. Perhaps an executive who kept stealing team members - feel free to improvise.

And finally the Sharks. These are things that worked against us. Perhaps an executive who kept stealing team members - feel free to improvise.

The Customer Wall

The Customer Wall

The Executive Wall

The Executive Wall

The Culture Wall

The Culture Wall

The Digital Business Wall

The Digital Business Wall

The Executive Portfolio Wall

The Executive Portfolio Wall

The Evaluation Wall

The Evaluation Wall

The Project Wall

The Project Wall

The Team Kanban Wall

The Team Kanban Wall

The Risks and Issues Wall

The Risks and Issues Wall

Fun Walls and Job Walls Obeya

Fun Walls and Job Walls Obeya

The Academy or Learning Wall

The Academy or Learning Wall

Cool Walls, Sail Boats, Blue Ocean, Friday Stories

Cool Walls, Sail Boats, Blue Ocean, Friday Stories

The Mosaic Metaphor

The Mosaic Metaphor

The Horizons Wall

The Horizons Wall

Really Simple Metrics

Really Simple Metrics

Very Subtle Gamification

Very Subtle Gamification