Chapter 1. THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME

1. See the Seventy-fifth Anniversary Issue of Good Housekeeping, May, 1960, “The Gift of Self,” a symposium by Margaret Mead, Jessamyn West, et al.

2. Lee Rainwater, Richard P. Coleman, and Gerald Handel, Workingman’s Wife, New York, 1959.

3. Betty Friedan, “If One Generation Can Ever Tell Another,” Smith Alumnae Quarterly, Northampton, Mass., Winter, 1961. I first became aware of “the problem that has no name” and its possible relationship to what I finally called “the feminine mystique” in 1957, when I prepared an intensive questionnaire and conducted a survey of my own Smith College classmates fifteen years after graduation. This questionnaire was later used by alumnae classes of Radcliffe and other women’s colleges with similar results.

4. Jhan and June Robbins, “Why Young Mothers Feel Trapped,” Redbook, September, 1960.

5. Marian Freda Poverman, “Alumnae on Parade,” Barnard Alumnae Magazine, July, 1957.

Chapter 2. THE HAPPY HOUSEWIFE HEROINE

1. Betty Friedan, “Women Are People Too!” Good Housekeeping, September, 1960. The letters received from women all over the United States in response to this article were of such emotional intensity that I was convinced that “the problem that has no name” is by no means confined to the graduates of the women’s Ivy League colleges.

2. In the 1960’s, an occasional heroine who was not a “happy housewife” began to appear in the women’s magazines. An editor of McCall’s explained it: “Sometimes we run an offbeat story for pure entertainment value.” One such novelette, which was written to order by Noel Clad for Good Housekeeping (January, 1960), is called “Men Against Women.” The heroine—a happy career woman—nearly loses child as well as husband.

Chapter 3. THE CRISIS IN WOMAN’S IDENTITY

1. Erik H. Erikson, Young Man Luther, A Study in Psychoanalysis and History, New York, 1958, pp. 15 ff. See also Erikson, Childhood and Society, New York, 1950, and Erikson, “The Problem of Ego Identity,” Journal of the American Psychoanalytical Association, Vol. 4, 1956, pp. 56–121.

Chapter 4. THE PASSIONATE JOURNEY

1. See Eleanor Flexner, Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States, Cambridge, Mass., 1959. This definitive history of the woman’s rights movement in the United States, published in 1959 at the height of the era of the feminine mystique, did not receive the attention it deserves, from either the intelligent reader or the scholar. In my opinion, it should be required reading for every girl admitted to a U.S. college. One reason the mystique prevails is that very few women under the age of forty know the facts of the woman’s rights movement. I am much indebted to Miss Flexner for many factual clues I might otherwise have missed in my attempt to get at the truth behind the feminine mystique and its monstrous image of the feminists.

2. See Sidney Ditzion, Marriage, Morals and Sex in America—A History of Ideas, New York, 1953. This extensive bibliographical essay by the librarian of New York University documents the continuous interrelationship between movements for social and sexual reform in America, and, specifically, between man’s movement for greater self-realization and sexual fulfillment and the woman’s rights movement. The speeches and tracts assembled reveal that the movement to emancipate women was often seen by the men as well as the women who led it in terms of “creating an equitable balance of power between the sexes” for “a more satisfying expression of sexuality for both sexes.”

3. Ibid., p. 107.

4. Yuri Suhl, Ernestine L. Rose and the Battle for Human Rights, New York, 1959, p. 158. A vivid account of the battle for a married woman’s right to her own property and earnings.

5. Flexner, op. cit., p. 30.

6. Elinor Rice Hays, Morning Star, A Biography of Lucy Stone, New York, 1961, p. 83.

7. Flexner, op. cit., p. 64.

8. Hays, op. cit., p. 136.

9. Ibid., p. 285.

10. Flexner, op. cit., p. 46.

11. Ibid., p. 73.

12. Hays, op. cit., p. 221.

13. Flexner, op. cit., p. 117.

14. Ibid., p. 235.

15. Ibid., p. 299.

16. Ibid., p. 173.

17. Ida Alexis Ross Wylie, “The Little Woman,” Harper’s, November, 1945.

Chapter 5. THE SEXUAL SOLIPSISM OF SIGMUND FREUD

1. Clara Thompson, Psychoanalysis: Evolution and Development, New York, 1950, pp. 131 ff:

Freud not only emphasized the biological more than the cultural, but he also developed a cultural theory of his own based on his biological theory. There were two obstacles in the way of understanding the importance of the cultural phenomena he saw and recorded. He was too deeply involved in developing his biological theories to give much thought to other aspects of the data he collected. Thus he was interested chiefly in applying to human society his theory of instincts. Starting with the assumption of a death instinct, for example, he then developed an explanation of the cultural phenomena he observed in terms of the death instinct. Since he did not have the perspective to be gained from knowledge of comparative cultures, he could not evaluate cultural processes as such. . . . Much which Freud believed to be biological has been shown by modern research to be a reaction to a certain type of culture and not characteristic of universal human nature.

2. Richard La Piere, The Freudian Ethic, New York, 1959, p. 62.

3. Ernest Jones, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, New York, 1953, Vol. I, p. 384.

4. Ibid., Vol. II (1955), p. 432.

5. Ibid., Vol. I, pp. 7–14, 294; Vol. II, p. 483.

6. Bruno Bettelheim, Love Is Not Enough: The Treatment of Emotionally Disturbed Children, Glencoe, III., 1950, pp. 7 ff.

7. Ernest L. Freud, Letters of Sigmund Freud, New York, 1960, Letter 10, p. 27; Letter 26, p. 71; Letter 65, p. 145.

8. Ibid., Letter 74, p. 60; Letter 76, pp. 161 ff.

9. Jones, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 176 ff.

10. Ibid., Vol. II, p. 422.

11. Ibid., Vol. I, p. 271:

His descriptions of sexual activities are so matter-of-fact that many readers have found them almost dry and totally lacking in warmth. From all I know of him, I should say that he displayed less than the average personal interest in what is often an absorbing topic. There was never any gusto or even savor in mentioning a sexual topic. . . . He always gave the impression of being an unusually chaste person—the word “puritanical” would not be out of place—and all we know of his early development confirms this conception.

12. Ibid., Vol. I, p. 102.

13. Ibid., Vol. I, pp. 110 ff.

14. Ibid., Vol. I, p. 124.

15. Ibid., Vol. I, p. 127.

16. Ibid., Vol. I, p. 138.

17. Ibid., Vol. I, p. 151.

18. Helen Walker Puner, Freud, His Life and His Mind, New York, 1947, p. 152.

19. Jones, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 121.

20. Ibid., Vol. I, pp. 301 ff. During the years Freud was germinating his sexual theory, before his own heroic self-analysis freed him from a passionate dependence on a series of men, his emotions were focused on a flamboyant nose-and-throat doctor named Fliess. This is one coincidence of history that was quite fateful for women. For Fliess had proposed, and obtained Freud’s lifelong allegiance to, a fantastic “scientific theory” which reduced all phenomena of life and death to “bisexuality,” expressed in mathematical terms through a periodic table based on the number 28, the female menstrual cycle. Freud looked forward to meetings with Fliess “as for the satisfying of hunger and thirst.” He wrote him: “No one can replace the intercourse with a friend that a particular, perhaps feminine side of me, demands.” Even after his own self-analysis, Freud still expected to die on the day predicted by Fliess’ periodic table, in which everything could be figured out in terms of the female number 28, or the male 23, which was derived from the end of one female menstrual period to the beginning of the next.

21. Ibid., Vol. I, p. 320.

22. Sigmund Freud, “Degradation in Erotic Life,” in The Collected Papers of Sigmund Freud, Vol. IV.

23. Thompson, op. cit., p. 133.

24. Sigmund Freud, “The Psychology of Women,” in New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, tr. by W. J. H. Sprott, New York, 1933, pp. 170 ff.

25. Ibid., p. 182.

26. Ibid., p. 184.

27. Thompson, op. cit., pp. 12 ff:

The war of 1914–18 further focussed attention on ego drives. . . . Another idea came into analysis around this period . . . and that was that aggression as well as sex might be an important repressed impulse. . . . The puzzling problem was how to include it in the theory of instincts. . . . Eventually Freud solved this by his second instinct theory. Aggression found its place as part of the death instinct. It is interesting that normal self-assertion, i.e., the impulse to master, control or come to self-fulfilling terms with the environment, was not especially emphasized by Freud.

28. Sigmund Freud, “Anxiety and Instinctual Life,” in New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, p. 149.

29. Marynia Farnham and Ferdinand Lundberg, Modern Woman: The Lost Sex, New York and London, 1947, pp. 142 ff.

30. Ernest Jones, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 446.

31. Helene Deutsch, The Psychology of Woman—A Psychoanalytical Interpretation, New York, 1944, Vol. I, pp. 224 ff.

32. Ibid., Vol. I, pp. 251 ff.

33. Sigmund Freud, “The Anatomy of the Mental Personality,” in New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, p. 96.

Chapter 6. THE FUNCTIONAL FREEZE, THE FEMININE PROTEST, AND MARGARET MEAD

1. Henry A. Bowman, Marriage for Moderns, New York, 1942, p. 21.

2. Ibid., pp. 22 ff.

3. Ibid., pp. 62 ff.

4. Ibid., pp. 74–76.

5. Ibid., pp. 66 ff.

6. Talcott Parsons, “Age and Sex in the Social Structure of the United States,” in Essays in Sociological Theory, Glencoe, Ill., 1949, pp. 223 ff.

7. Talcott Parsons, “An Analytical Approach to the Theory of Social Stratification,” op. cit., pp. 174 ff.

8. Mirra Komarovsky, Women in the Modern World, Their Education and Their Dilemmas, Boston, 1953, pp. 52–61.

9. Ibid., p. 66.

10. Ibid., pp. 72–74.

11. Mirra Komarovsky, “Functional Analysis of Sex Roles,” American Sociological Review, August, 1950. See also “Cultural Contradictions and Sex Roles,” American Journal of Sociology, November, 1946.

12. Kingsley Davis, “The Myth of Functional Analysis as a Special Method in Sociology and Anthropology,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 24, No. 6, December, 1959, pp. 757–772. Davis points out that functionalism became more or less identical with sociology itself. There is provocative evidence that the very study of sociology, in recent years, has persuaded college women to limit themselves to their “functional” traditional sexual role. A report on “The Status of Women in Professional Sociology” (Sylvia Fleis Fava, American Sociological Review, Vol. 25, No. 2, April, 1960) shows that while most of the students in sociology undergraduate classes are women, from 1949 to 1958 there was a sharp decline in both the number and proportion of degrees in sociology awarded to women. (4,143 B.A.’s in 1949 down to a low of 3,200 in 1955, 3,606 in 1958). And while one-half to two-thirds of the undergraduate degrees in sociology were awarded to women, women received only 25 to 43 per cent of the master’s degrees, and only 8 to 19 per cent of the Ph.D.’s. While the number of women earning graduate degrees in all fields has declined sharply during the era of the feminine mystique, the field of sociology showed, in comparison to other fields, an unusually high “mortality” rate.

13. Margaret Mead, Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies, New York, 1935, pp. 279 ff.

14. Margaret Mead, From the South Seas, New York, 1939, p. 321.

15. Margaret Mead, Male and Female, New York, 1955, pp. 16–18.

16. Ibid., p. 26.

17. Ibid., footnotes, pp. 289 ff:

I did not begin to work seriously with the zones of the body until I went to the Arapesh in 1931. While I was generally familiar with Freud’s basic work on the subject, I had not seen how it might be applied in the field until I read Geza Roheim’s first field report, “Psychoanalysis of Primitive Culture Types” . . . I then sent home for abstracts of K. Abraham’s work. After I became acquainted with Erik Homburger Erikson’s systematic handling of these ideas, they became an integral part of my theoretical equipment.

18. Ibid., pp. 50 f.

19. Ibid., pp. 72 ff.

20. Ibid., pp. 84 ff.

21. Ibid., p. 85.

22. Ibid., pp. 125 ff.

23. Ibid., pp. 135 ff.

24. Ibid., pp. 274 ff.

25. Ibid., pp. 278 ff.

26. Ibid., pp. 276–285.

27. Margaret Mead, Introduction to From the South Seas, New York, 1939, p. xiii. “It was no use permitting children to develop values different from those of their society . . .”

28. Marie Jahoda and Joan Havel, “Psychological Problems of Women in Different Social Roles—A Case History of Problem Formulation in Research,” Educational Record, Vol. 36, 1955, pp. 325–333.

Chapter 7. THE SEX-DIRECTED EDUCATORS

1. Mabel Newcomer, A Century of Higher Education for Women, New York, 1959, pp. 45 ff. The proportion of women among college students in the U.S. increased from 21 per cent in 1870 to 47 per cent in 1920; it had declined to 35.2 per cent in 1958. Five women’s colleges had closed; 21 had become coeducational; 2 had become junior colleges. In 1956, 3 out of 5 women in the coeducational colleges were taking secretarial, nursing, home economics, or education courses. Less than 1 out of 10 doctorates were granted to women, compared to 1 in 6 in 1920, 13 per cent in 1940. Not since before World War I have the percentages of American women receiving professional degrees been as consistently low as in this period. The extent of the retrogression of American women can also be measured in terms of their failure to develop to their own potential. According to Womanpower, of all the young women capable of doing college work, only one out of four goes to college, compared to one out of two men; only one out of 300 women capable of earning a Ph.D. actually does so, compared to one out of 30 men. If the present situation continues, American women may soon rank among the most “backward” women in the world. The U.S. is probably the only nation where the proportion of women gaining higher education has decreased in the past 20 years; it has steadily increased in Sweden, Britain, and France, as well as the emerging nations of Asia and the communist countries. By the 1950’s, a larger proportion of French women were obtaining higher education than American women; the proportion of French women in the professions had more than doubled in fifty years. The proportion of French women in the medical profession alone is five times that of American women; 70 per cent of the doctors in the Soviet Union are women, compared to 5 per cent in America. See Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein, Women’s Two Roles—Home and Work, London, 1956, pp. 33–64.

2. Mervin B. Freedman, “The Passage through College,” in Personality Development During the College Years, ed. by Nevitt Sanford, Journal of Social Issues, Vol. XII, No. 4, 1956, pp. 15 ff.

3. John Bushnel, “Student Culture at Vassar,” in The American College, ed. by Nevitt Sanford, New York and London, 1962, pp. 509 ff.

4. Lynn White, Educating Our Daughters, New York, 1950, pp. 18–48.

5. Ibid., p. 76.

6. Ibid., pp. 77 ff.

7. Ibid., p. 79.

8. See Dael Wolfle, America’s Resources of Specialized Talent, New York, 1954.

9. Cited in an address by Judge Mary H. Donlon in proceedings of “Conference on the Present Status and Prospective Trends of Research on the Education of Women,” 1957, American Council on Education, Washington, D.C.

10. See “The Bright Girl: A Major Source of Untapped Talent,” Guidance Newsletter, Science Research Associates Inc., Chicago, Ill., May, 1959.

11. See Dael Wolfle, op. cit.

12. John Summerskill, “Dropouts from College,” in The American College, p. 631.

13. Joseph M. Jones, “Does Overpopulation Mean Poverty?” Center for International Economic Growth, Washington, 1962. See also United Nations Demographic Yearbook, New York, 1960, pp. 580 ff. By 1958, in the United States, more girls were marrying from 15 to 19 years of age than from any other age group. In all of the other advanced nations, and many of the emerging underdeveloped nations, most girls married from 20 to 24 or after 25. The U.S. pattern of teenage marriage could only be found in countries like Paraguay, Venezuela, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Egypt, Iraq and the Fiji Islands.

14. Nevitt Sanford, “Higher Education as a Social Problem” in The American College, p. 23.

15. Elizabeth Douvan and Carol Kaye, “Motivational Factors in College Entrance,” in The American College, pp. 202–206.

16. Ibid., pp. 208 ff.

17. Esther Lloyd-Jones, “Women Today and Their Education,” Teacher’s College Record, Vol. 57, No. 1, October, 1955; and No. 7, April, 1956. See also Opal David, The Education of Women—Signs for the Future, American Council on Education, Washington, D.C., 1957.

18. Mary Ann Guitar, “College Marriage Courses—Fun or Fraud?” Mademoiselle, February, 1961.

19. Helen Deutsch, op. cit., Vol. 1, p. 290.

20. Mirra Komarovsky, op. cit., p. 70. Research studies indicate that 40 per cent of college girls “play dumb” with men. Since the ones who do not include those not excessively overburdened with intelligence, the great majority of American girls who are gifted with high intelligence evidently learn to hide it.

21. Jean Macfarlane and Lester Sontag, Research reported to the Commission on the Education of Women, Washington, D.C., 1954, (mimeo ms.).

22. Harold Webster, “Some Quantitative Results,” in Personality Development During the College Years, ed. by Nevitt Sanford, Journal of Social Issues, 1956, Vol. 12, No. 4, p. 36.

23. Nevitt Sanford, Personality Development During the College Years, Journal of Social Issues, 1956, Vol. 12, No. 4.

24. Mervin B. Freedman, “Studies of College Alumni,” in The American College, p. 878.

25. Lynn White, op. cit., p. 117.

26. Ibid., pp. 119 ff.

27. Max Lerner, America As a Civilization, New York, 1957, pp. 608–611:

The crux of it lies neither in the biological nor economic disabilities of women but in their sense of being caught between a man’s world in which they have no real will to achieve and a world of their own in which they find it hard to be fulfilled. . . . When Walt Whitman exhorted women “to give up toys and fictions and launch forth, as men do, amid real, independent, stormy life,” he was thinking—as were many of his contemporaries—of the wrong kind of equalitarianism. . . . If she is to discover her identity, she must start by basing her belief in herself on her womanliness rather than on the movement for feminism. Margaret Mead has pointed out that the biological life cycle of the woman has certain well-marked phases from menarche through the birth of her children to her menopause; that in these stages of her life cycle, as in her basic bodily rhythms, she can feel secure in her womanhood and does not have to assert her potency as the male does. Similarly, while the multiple roles that she must play in life are bewildering, she can fulfill them without distraction if she knows that her central role is that of a woman. . . . Her central function, however, remains that of creating a life style for herself and for the home in which she is life creator and life sustainer.

28. See Philip E. Jacob, Changing Values in College, New York, 1957.

29. Margaret Mead, “New Look at Early Marriages,” interview in U.S. News and World Report, June 6, 1960.

Chapter 8. THE MISTAKEN CHOICE

1. See the United Nations Demographic Yearbook, New York, 1960, pp. 99–118 and pp. 476–490; p. 580. The annual rate of population increase in the U.S. in the years 1955–59 was far higher than that of other Western nations, and higher than that of India, Japan, Burma, and Pakistan. In fact, the increase for North America (1.8) exceeded the world rate (1.7). The rate for Europe was .8; for the USSR 1.7; Asia 1.8; Africa 1.9; and South America 2.3. The increase in the underdeveloped nations was, of course, largely due to medical advances and the drop in death rate; in America it was almost completely due to increased birth rate, earlier marriage, and larger families. For the birth rate continued to rise in the U.S. from 1950 to 1959, while it was falling in countries like France, Norway, Sweden, the USSR, India and Japan. The U.S. was the only so-called “advanced” nation, and one of the few nations in the world where, in 1958, more girls married at ages 15 to19 than at any other age. Even the other countries which showed a rise in the birth rate—Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, Chile, New Zealand, Peru—did not show this phenomenon of teenage marriage.

2. See “The Woman with Brains (continued),” New York Times Magazine, January 17, 1960, for the outraged letters in response to an article by Marya Mannes, “Female Intelligence—Who Wants It?” New York Times Magazine, January 3, 1960.

3. See National Manpower Council, Womanpower, New York, 1957. In 1940, more than half of all employed women in the U.S. were under 25, and one-fifth were over 45. In the 1950’s peak participation in paid employment occurs among young women of 18 and 19—and women over 45, the great majority of whom hold jobs for which little training is required. The new preponderance of older married women in the working force is partly due to the fact that so few women in their twenties and thirties now work, in the U.S. Two out of five of all employed women are now over 45, most of them wives and mothers, working part time at unskilled work. Those reports of millions of American wives working outside the home are misleading in more ways than one: of all employed women, only one-third hold full-time jobs, one-third work full time only part of the year—for instance, extra saleswomen in the department stores at Christmas—and one-third work part time, part of the year. The women in the professions are, for the most part, that dwindling minority of single women; the older untrained wives and mothers, like the untrained 18-year-olds, are concentrated at the lower end of the skill ladder and the pay scales, in factory, service, sales and office work. Considering the growth in the population, and the increasing professionalization of work in America, the startling phenomenon is not the much-advertised, relatively insignificant increase in the numbers of American women who now work outside the home, but the fact that two out of three adult American women do not work outside the home, and the increasing millions of young women who are not skilled or educated for work in any profession. See also Theodore Caplow, The Sociology of Work, 1954, and Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein, Women’s Two Roles—Home and Work, London, 1956.

4. Edward Strecker, Their Mother’s Sons, Philadelphia and New York, 1946, pp. 52–59.

5. Ibid., pp. 31 ff.

6. Farnham and Lundberg, Modern Woman: The Lost Sex, p. 271. See also Lynn White, Educating Our Daughters, p. 90.

Preliminary results of the careful study of American sex habits being conducted at the University of Indiana by Dr. A. C. Kinsey indicate that there is an inverse correlation between education and the ability of a woman to achieve habitual orgastic experience in marriage. According to the present evidence, admittedly tentative, nearly 65 per cent of the marital intercourse had by women with college backgrounds is had without orgasm for them, as compared to about 15 per cent for married women who have gone no further than grade school.

7. Alfred C. Kinsey, et al., Staff of the Institute for Sex Research, Indiana University, Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, Philadelphia and London, 1953, pp. 378 ff.

8. Lois Meek Stolz, “Effects of Maternal Employment on Children: Evidence from Research,” Child Development, Vol. 31, No. 4, 1960, pp. 749–782.

9. H. F. Southard, “Mothers’ Dilemma: To Work or Not?” New York Times Magazine, July 17, 1960.

10. Stolz, op. cit. See also Myrdal and Klein, op. cit., pp. 125 ff.

11. Benjamin Spock, “Russian Children Don’t Whine, Squabble or Break Things—Why?” Ladies’ Home Journal, October, 1960.

12. David Levy, Maternal Overprotection, New York, 1943.

13. Arnold W. Green, “The Middle-Class Male Child and Neurosis,” American Sociological Review, Vol. II, No. 1, 1946.

Chapter 9. THE SEXUAL SELL

1. The studies upon which this chapter is based were done by the Staff of the Institute for Motivational Research, directed by Dr. Ernest Dichter. They were made available to me through the courtesy of Dr. Dichter and his colleagues, and are on file at the Institute, in Croton-on-Hudson, New York.

2. Harrison Kinney, Has Anybody Seen My Father?, New York, 1960.

Chapter 10. HOUSEWIFERY EXPANDS TO FILL THE TIME AVAILABLE

1. Jhan and June Robbins, “Why Young Mothers Feel Trapped,” Redbook, September, 1960.

2. Carola Woerishoffer Graduate Department of Social Economy and Social Research, “Women During the War and After,” Bryn Mawr College, 1945.

3. Theodore Caplow points out in The Sociology of Work, p. 234, that with the rapidly expanding economy since 1900, and the extremely rapid urbanization of the United States, the increase in the employment of women from 20.4 per cent in 1900 to 28.5 per cent in 1950 was exceedingly modest. Recent studies of time spent by American housewives on housework, which confirm my description of the Parkinson effect, are summarized by Jean Warren, “Time: Resource or Utility,” Journal of Home Economics, Vol. 49, January, 1957, pp. 21 ff. Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein in Women’s Two Roles—Home and Work cite a French study which showed that working mothers reduced time spent on housework by 30 hours a week, compared to a full-time housewife. The work week of a working mother with three children broke down to 35.2 hours on the job, 48.3 hours on housework; the full-time housewife spent 77.7 hours on housework. The mother with a full-time job or profession, as well as the housekeeping and children, worked only one hour a day longer than the full-time housewife.

4. Robert Wood, Suburbia, Its People and Their Politics, Boston, 1959.

5. See “Papa’s Taking Over the PTA Mama Started,” New York Herald Tribune, February 10, 1962. At the 1962 national convention of Parent-Teacher Associations, it was revealed that 32 per cent of the 46,457 PTA presidents are now men. In certain states the percentage of male PTA heads is even higher, including New York (33 per cent), Connecticut (45 per cent) and Delaware (80 per cent).

6. Nanette E. Scofield, “Some Changing Roles of Women in Suburbia: A Social Anthropological Case Study,” transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 22, No. 6, April, 1960.

7. Mervin B. Freedman, “Studies of College Alumni,” in The American College, pp. 872 ff.

8. Murray T. Pringle, “Women Are Wretched Housekeepers,” Science Digest, June, 1960.

9. See Time, April 20, 1959.

10. Farnham and Lundberg, Modern Women: The Lost Sex, p. 369.

11. Edith M. Stern, “Women Are Household Slaves,” American Mercury, January, 1949.

12. Russell Lynes, “The New Servant Class,” in A Surfeit of Honey, New York, 1957, pp. 49–64.

Chapter 11. THE SEX-SEEKERS

1. Several social historians have commented on America’s sexual pre-occupation from the male point of view. “America has come to stress sex as much as any civilization since the Roman,” says Max Lerner (America as A Civilization, p. 678). David Riesman in The Lonely Crowd (New Haven, 1950, p. 172 ff.) calls sex “the Last Frontier.”

More than before, as job-mindedness declines, sex permeates the daytime as well as the playtime consciousness. It is viewed as a consumption good not only by the old leisure classes but by the modern leisure masses. . . .

One reason for the change is that women are no longer objects for the acquisitive consumer but are peer-groupers themselves. . . . Today, millions of women, freed by technology from many household tasks, given by technology many aids to romance, have become pioneers with men on the frontiers of sex. As they become knowing consumers, the anxiety of men lest they fail to satisfy the women also grows . . .

It is mainly the clinicians who have noted that the men are often less eager now than their wives as sexual “consumers.” The late Dr. Abraham Stone, whom I interviewed shortly before his death, said that the wives complain more and more of sexually “inadequate” husbands. Dr. Karl Menninger reports that for every wife who complains of her husband’s excessive sexuality, a dozen wives complain that their husbands are apathetic or impotent. These “problems” are cited in the mass media as additional evidence that American women are losing their “femininity”—and thus provide new ammunition for the mystique. See John Kord Lagemann, “The Male Sex,” Redbook, December, 1956.

2. Albert Ellis, The Folklore of Sex, New York, 1961, p. 123.

3. See the amusing parody, “The Pious Pornographers,” by Ray Russell, in The Permanent Playboy, New York, 1959.

4. A. C. Spectorsky, The Exurbanites, New York, 1955, p. 223.

5. Nathan Ackerman, The Psychodynamics of Family Life, New York, 1958, pp. 112–127.

6. Evan Hunter, Strangers When We Meet, New York, 1958, pp. 231–235.

7. Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, pp. 353 ff., p. 426.

8. Doris Menzer-Benaron M.D., et al., “Patterns of Emotional Recovery from Hysterectomy,” Psychosomatic Medicine, XIX, No. 5, September, 1957, pp. 378–388.

9. The fact that 75 per cent to 85 per cent of young mothers in America today feel negative emotions—resentment, grief, disappointment, outright rejection—when they become pregnant for the first time has been established in many studies. In fact, the perpetrators of the feminine mystique report findings to reassure young mothers that they are only “normal” in feeling this strange rejection of pregnancy—and that the only real problem is their “guilt” over feeling it. Thus Redbook magazine, in “How Women Really Feel about Pregnancy” (November, 1958), reports that the Harvard School of Public Health found 80 to 85 per cent of “normal women reject the pregnancy when they become pregnant”; Long Island College Clinic found that less than a fourth of women are “happy” about their pregnancy; a New Haven study finds only 17 of 100 women “pleased” about having a baby. Comments the voice of editorial authority:

The real danger that arises when a pregnancy is unwelcome and filled with troubled feelings is that a woman may become guilty and panic-stricken because she believes her reactions are unnatural or abnormal. Both marital and mother-child relations can be damaged as a result. . . . Sometimes a mental-health specialist is needed to allay guilt feelings. . . . Nor is there any time when a normal woman does not have feelings of depression and doubt when she learns that she is pregnant.

Such articles never mention the various studies which indicate that women in other countries, both more and less advanced than the United States, and even American “career” women, are less likely to experience this emotional rejection of pregnancy. Depression at pregnancy may be “normal” for the housewife-mother in the era of the feminine mystique, but it is not normal to motherhood. As Ruth Benedict said, it is not biological necessity, but our culture which creates the discomforts, physical and psychological, of the female cycle. See her Continuities and Discontinuities in Cultural Conditioning.

10. See William J. Goode, After Divorce, Glencoe, Ill., 1956.

11. A. C. Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Philadelphia and London, 1948, p. 259, pp. 585–588.

12. The male contempt for the American woman, as she has molded herself according to the feminine mystique, is depressingly explicit in the July, 1962 issue of Esquire, “The American Woman, A New Point of View.” See especially “The Word to Women—‘No’” by Robert Alan Aurthur, p. 32. The sexlessness of the American female sex-seekers is eulogized by Malcolm Muggeridge (“Bedding Down in the Colonies,” p. 84): “How they mortify the flesh in order to make it appetizing! Their beauty is a vast industry, their enduring allure a discipline which nuns or athletes might find excessive. With too much sex to be sensual, and too ravishing to ravish, age cannot wither them nor custom stale their infinite monotony.”

13. Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, p. 631.

14. See Donald Webster Cory, The Homosexual in America, New York, 1960, preface to second edition, pp. xxii ff. Also Albert Ellis, op. cit., pp. 186–190. Also Seward Hiltner, “Stability and Change in American Sexual Patterns,” in Sexual Behavior in American Society, Jerome Himelhoch and Sylvia Fleis Fava, eds., New York, 1955, p. 321.

15. Sigmund Freud, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, New York, 1948, p. 10.

16. Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, pp. 610 ff. See also Donald Webster Cory, op. cit., pp. 97 ff.

17. Birth out of wedlock increased 194 per cent from 1956 to 1962; venereal disease among young people increased 132 per cent. (Time, March 16, 1962).

18. Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, pp. 348 ff., 427–433.

19. Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, pp. 293, 378, 382.

20. Clara Thompson, “Changing Concepts of Homosexuality in Psychoanalysis” in A Study of Interpersonal Relations, New Contributions to Psychiatry, Patrick Mullahy, ed., New York, 1949, pp. 218 ff.

21. Erich Fromm, “Sex and Character: the Kinsey Report Viewed from the Standpoint of Psychoanalysis,” in Sexual Behavior in American Society, p. 307.

22. Carl Binger, “The Pressures on College Girls Today,” Atlantic Monthly, February, 1961.

23. Sallie Bingham, “Winter Term,” Mademoiselle, July, 1958.

Chapter 12. PROGRESSIVE DEHUMANIZATION: THE COMFORTABLE CONCENTRATION CAMP

1. Marjorie K. McCorquodale, “What They Will Die for in Houston,” Harper’s, October, 1961.

2. See David Riesman, The Lonely Crowd; also Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom, New York and Toronto, 1941, pp. 185–206. Also Erik H. Erikson, Childhood and Society, p. 239.

3. David Riesman, introduction to Edgar Friedenberg’s The Vanishing Adolescent, Boston, 1959.

4. Harold Taylor, “Freedom and Authority on the Campus,” in The American College, pp. 780 ff.

5. David Riesman, introduction to Edgar Friedenberg’s The Vanishing Adolescent.

6. See Eugene Kinkead, In Every War but One, New York, 1959. There has been an attempt in recent years to discredit or soft-pedal these findings. But a taped record of a talk given before the American Psychiatric Association in 1958 by Dr. William Mayer, who had been on one of the Army teams of psychiatrists and intelligence officers who interviewed the returning prisoners in 1953 and analyzed the data, caused many pediatricians and child specialists to ask, in the words of Dr. Spock: “Are unusually permissive, indulgent parents more numerous today—and are they weakening the character of our children?” (Benjamin Spock, “Are We Bringing Up Our Children Too ‘Soft’ for the Stern Realities They Must Face?” Ladies’ Home Journal, September, 1960.) However unpleasantly injurious to American pride, there must be some explanation for the collapse of the American GI prisoners in Korea, as it differed not only from the behavior of American soldiers in previous wars, but from the behavior of soldiers of other nations in Korea. No American soldier managed to escape from the enemy prison camps, as they had in every other war. The shocking 38 per cent death rate was not explainable, even according to military authorities, on the basis of the climate, food, or inadequate medical facilities in the camps, nor was it caused by brutality or torture. “Give-up-itis” is how one doctor described the disease the Americans died from; they simply spent the days curled up under blankets, cutting down their diet to water alone, until they were dead, usually within three weeks. This seemed to be an American phenomenon. Turkish prisoners, who were also part of the UN force in Korea, lost no men by disease or starvation; they stuck together, obeyed their officers, adhered to health regulations, cooperated in the care of their sick, and refused to inform on one another.

7. Edgar Friedenberg, The Vanishing Adolescent, pp. 212 ff.

8. Andras Angyal, M.D., “Evasion of Growth,” American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 110, No. 5, November, 1953, pp. 358–361. See also Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom, pp. 138–206.

9. See Richard E. Gordon and Katherine K. Gordon, “Social Factors in the Prediction and Treatment of Emotional Disorders of Pregnancy,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1959, 77:5, pp. 1074–1083; also Richard E. Gordon and Katherine K. Gordon, “Psychiatric Problems of a Rapidly Growing Suburb,” American Medical Association Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 1958, Vol. 79; “Psychosomatic Problems of a Rapidly Growing Suburb,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 1959, 170:15; and “Social Psychiatry of a Mobile Suburb,” International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 1960, 6:1, 2, pp. 89–99. Some of these findings were popularized in the composite case histories of The Split Level Trap, written by the Gordons in collaboration with Max Gunther (New York, 1960).

10. Richard E. Gordon, “Sociodynamics and Psychotherapy,” A.M.A. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, April, 1959, Vol. 81, pp. 486–503.

11. Adelaide M. Johnson and S. A. Szurels, “The Genesis of Antisocial Acting Out in Children and Adults,” Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 1952, 21:323–343.

12. Ibid.

13. Beata Rank, “Adaptation of the Psychoanalytical Technique for the Treatment of Young Children with Atypical Development,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, XIX, 1, January, 1949.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Beata Rank, Marian C. Putnam, and Gregory Rochlin, M.D., “The Significance of the ‘Emotional Climate’ in Early Feeding Difficulties,” Psychosomatic Medicine, X, 5, October, 1948.

17. Richard E. Gordon and Katherine K. Gordon, “Social Psychiatry of a Mobile Suburb,” op. cit., pp. 89–100.

18. Ibid.

19. Oscar Sternbach, “Sex Without Love and Marriage Without Responsibility,” an address presented at the 38th Annual Conference of The Child Study Association of America, March 12, 1962, New York City (mimeo ms.).

20. Bruno Bettelheim, The Informed Heart—Autonomy in a Mass Age, Glencoe, Ill., 1960.

21. Ibid., pp. 162–169.

22. Ibid., p. 231.

23. Ibid., pp. 233 ff.

24. Ibid., p. 265.

Chapter 13. THE FORFEITED SELF

1. Rollo May, “The Origins and Significance of the Existential Movement in Psychology,” in Existence, A New Dimension in Psychiatry and Psychology, Rollo May, Ernest Angel and Henri F. Ellenberger, eds., New York, 1958, pp. 30 ff. (See also Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom, pp. 269 ff.; A. H. Maslow, Motivation and Personality, New York, 1954; David Riesman, The Lonely Crowd.)

2. Rollo May, “Contributions of Existential Psychotherapy,” in Existence, A New Dimension in Psychiatry and Psychology, p. 87.

3. Ibid., p. 52.

4. Ibid., p. 53.

5. Ibid., pp. 59 ff.

6. See Kurt Goldstein, The Organism, A Holistic Approach to Biology Derived From Pathological Data on Man, New York and Cincinnati, 1939; also Abstract and Concrete Behavior, Evanston, Ill., 1950; Case of Idiot Savant (with Martin Scheerer), Evanston, 1945; Human Nature in the Light of Psychopathology, Cambridge, 1947; After-Effects of Brain Injuries in War, New York, 1942.

7. Eugene Minkowski, “Findings in a Case of Schizophrenic Depression,” in Existence, A New Dimension in Psychiatry and Psychology, pp. 132 ff.

8. O. Hobart Mowrer, “Time as a Determinant in Integrative Learning,” in Learning Theory and Personality Dynamics, New York, 1950.

9. Eugene Minkowski, op. cit., pp. 133–138:

We think and act and desire beyond that death which, even so, we could not escape. The very existence of such phenomena as the desire to do something for future generations clearly indicates our attitude in this regard. In our patient, it was this propulsion toward the future which seemed to be totally lacking. . . . In this personal impetus, there is an element of expansion; we go beyond the limits of our own ego and leave a personal imprint on the world about us, creating works which sever themselves from us to live their own lives. This accompanies a specific, positive feeling which we call contentment—that pleasure which accompanies every finished action or firm decision. As a feeling, it is unique. . . . Our entire individual evolution consists in trying to surpass that which has already been done. When our mental life dims, the future closes in front of us . . .

10. Rollo May, “Contributions of Existential Psychotherapy,” pp. 31 ff. In Nietz-sche’s philosophy, human individuality and dignity are “given or assigned to us as a task which we ourselves must solve”; in Tillich’s philosophy, if you do not have the “courage to be,” you lose your own being; in Sartre’s, you are your choices.

11. A. H. Maslow, Motivation and Personality, p. 83.

12. A. H. Maslow, “Some Basic Propositions of Holistic-Dynamic Psychology,” an unpublished paper, Brandeis University.

13. Ibid.

14. A. H. Maslow, “Dominance, Personality and Social Behavior in Women,” Journal of Social Psychology, 1939, Vol. 10, pp. 3–39; and “Self Esteem (Dominance-Feeling) and Sexuality in Women,” Journal of Social Psychology, 1942, Vol. 16, pp. 259–294.

15. A. H. Maslow, “Dominance, Personality and Social Behavior in Women,” op. cit., pp. 3–11.

16. Ibid., pp. 13 ff.

17. Ibid., p. 180.

18. A. H. Maslow, “Self-Esteem (Dominance-Feeling) and Sexuality in Women,” p. 288. Maslow points out, however, that women with “ego insecurity” pretended a “self-esteem” they did not actually have. Such women had to “dominate,” in the ordinary sense, in their sexual relations, to compensate for their “ego insecurity”; thus, they were either castrative or masochistic. As I have pointed out, such women must have been very common in a society which gives women little chance for true self-esteem; this was undoubtedly the basis of the man-eating myth, and of Freud’s equation of femininity with castrative penis envy and/or masochistic passivity.

19. A. H. Maslow, Motivation and Personality, pp. 200 ff.

20. Ibid., pp. 211 ff.

21. Ibid., p. 214.

22. Ibid., pp. 242 ff.

23. Ibid., pp. 257 ff. Maslow found that his self-actualizing people “have in unusual measure the rare ability to be pleased rather than threatened by the partner’s triumphs. . . . A most impressive example of this respect is the ungrudging pride of such a man in his wife’s achievements even where they outshine his.” (Ibid., p. 252).

24. Ibid., p. 245.

25. Ibid., p. 255.

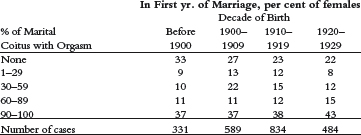

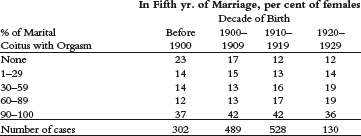

26. A. C. Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, pp. 356 ff.; Table 97, p. 397; Table 104, p. 403.

Decade of Birth vs. Percentage of

Marital Coitus Leading to Orgasm

27. Ibid., p. 355.

28. See Judson T. Landis, “The Women Kinsey Studied,” George Simpson, “Nonsense about Women,” and A. H. Maslow and James M. Sakoda, “Volunteer Error in the Kinsey Study,” in Sexual Behavior in American Society.

29. Ernest W. Burgess and Leonard S. Cottrell, Jr., Predicting Success or Failure in Marriage, New York, 1939, p. 271.

30. A. C. Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, p. 403.

31. Sylvan Keiser, “Body Ego During Orgasm,” Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 1952, Vol. XXI, pp. 153–166:

Individuals of this group are characterized by failure to develop adequate egos. . . . Their anxious devotion to, and lavish care of, their bodies belies the inner feelings of hollowness and inadequacy. . . . These patients have little sense of their own identity and are always ready to take on the personality of someone else. They have few personal convictions, and yield readily to the opinions of others. . . . It is chiefly among such patients that coitus can be enjoyed only up to the point of orgasm. . . . They dared not allow themselves uninhibited progression to orgasm with its concomitant loss of control, loss of awareness of the body, or death. . . . In instances of uncertainty about the structure and boundaries of the body image, one might say that the skin does not serve as an envelope which sharply defines the transition from the self to the environment; the one gradually merges into the other; there is no assurance of being a distinct entity endowed with the strength to give of itself without endangering one’s own integrity.

32. Lawrence Kubie, “Psychiatric Implications of the Kinsey Report,” in Sexual Behavior in American Society, pp. 270 ff:

This simple biologic aim is overlaid by many subtle goals of which the individual himself is usually unaware. Some of these are attainable; some are not. Where the majority are attainable, then the end result of sexual activity is an afterglow of peaceful completion and satisfaction. Where, however, the unconscious goals are unattainable, then whether orgasm has occurred or not, there remains a post-coital state of unsated need, and sometimes of fear, rage or depression.

33. Erik H. Erikson, Childhood and Society, pp. 239–283, 367–380. See also Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom and Man for Himself; and David Riesman, The Lonely Crowd.

34. See Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein (Women’s Two Roles), who point out that the number of American women now working outside the home seems greater than it is because the base from which the comparison is usually made was unusually small: a century ago the proportion of American women working outside the home was far smaller than in the European countries. In other words, the woman problem in America was probably unusually severe because the displacement of American women from essential work and identity in society was far more drastic—primarily because of the extremely rapid growth and industrialization of the American economy. The women who had grown with the men in the frontier days were banished almost overnight to anomie—which is a very expressive sociological name for that sense of non-existence or non-identity suffered by one who has no real place in society—when the important work left the home, where they stayed. In contrast, in France where industrialization was slower, and farms and small family-size shops are still fairly important in the economy, women a century ago still worked in large numbers—in field and shop—and today the majority of French women are not full-time housewives in the American sense of the mystique, for an enormous number still work in the fields, in addition to that one out of three who, as in America, work in industry, sales, offices, and professions. The growth of women in France has much more closely paralleled the growth of the society, since the proportion of French women in the professions has doubled in fifty years. It is interesting to note that the feminine mystique does not prevail in France, to the extent that it does here; there is a legitimate image in France of a feminine career woman and feminine intellectual, and French men seem responsive to women sexually, without equating femininity either with glorified emptiness or that man-eating castrative mom. Nor has the family been weakened—in actuality or mystique—by women’s work in industry and profession. Myrdal and Klein show that the French career women continue to have children—but not the great number the new educated American housewives produce.

35. Sidney Ditzion, Marriage, Morals and Sex in America, A History of Ideas, New York, 1953, p. 277.

36. William James, Psychology, New York, 1892, p. 458.

Chapter 14. A NEW LIFE PLAN FOR WOMEN

1. See “Mother’s Choice: Manager or Martyr,” and “For a Mother’s Hour,” New York Times Magazine, January 14, 1962, and March 18, 1962.

2. The sense that work has to be “real,” and not just “therapy” or busywork, to provide a basis for identity becomes increasingly explicit in the theories of the self, even when there is no specific reference to women. Thus, in defining the beginnings of “identity” in the child, Erikson says in Childhood and Society (p. 208):

The growing child must, at every step, derive a vitalizing sense of reality from the awareness that his individual way of mastering experience (his ego synthesis) is a successful variant of a group identity and is in accord with its space-time and life plan.

In this children cannot be fooled by empty praise and condescending encouragement. They may have to accept artificial bolstering of their self-esteem in lieu of something better, but their ego identity gains real strength only from wholehearted and consistent recognition of real accomplishment—i.e., of achievement that has meaning in the culture.

3. Nanette E. Scofield, “Some Changing Roles of Women in Suburbia: A Social Anthropological Case Study,” transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 22, 6, April, 1960.

4. Polly Weaver, “What’s Wrong with Ambition?” Mademoiselle, September, 1956.

5. Edna G. Rostow, “The Best of Both Worlds,” Yale Review, March, 1962.

6. Ida Fisher Davidoff and May Elish Markewich, “The Postparental Phase in the Life Cycle of Fifty College-Educated Women,” unpublished doctoral study, Teachers College, Columbia University, 1961. These fifty educated women had been full-time housewives and mothers throughout the years their children were in school. With the last child’s departure, the women suffering severe distress because they had no deep interest beyond the home included a few whose actual ability and achievement were high; these women had been leaders in community work, but they felt like “phonies,” “frauds,” earning respect for “work a ten-year-old could do.” The authors’ own orientation in the functional-adjustment school makes them deplore the fact that education gave these women “unrealistic” goals (a surprising number, now in their fifties and sixties, still wished they had been doctors). However, those women who had pursued interests—which in every case had begun in college—and were working now in jobs or politics or art, did not feel like “phonies,” or even suffer the expected distress at menopause. Despite the distress of those who lacked such interests, none of them, after the child-bearing years were over, wanted to go back to school; there were simply too few years left to justify the effort. So they continued “woman’s role” by acting as mothers to their own aged parents or by finding pets, plants, or simply “people as my hobby” to take the place of their children. The interpretation of the two family-life educators—who themselves became professional marriage counselors in middle age—is interesting:

For those women in our group who had high aspirations or high intellectual endowment or both, the discrepancy between some of the values stressed in our success-and-achievement oriented society and the actual opportunities open to the older, untrained women was especially disturbing. . . . The door open to the woman with a skill was closed to the one without training, even if she was tempted to try to find a place for herself among the gainfully employed. The reality hazards of the work situation seemed to be recognized by most, however. They felt neither prepared for the kind of job which might appeal to them, nor willing to take the time and expend the energy which would be required for training, in view of the limited number of active years ahead. . . . The lack of pressure resulting from reduced responsibility had to be handled. . . . As the primary task of motherhood was finished, the satisfactions of volunteer work, formerly a secondary outlet, seemed to be diminishing. . . . The cultural activities of the suburbs were limited. . . . Even in the city, adult education . . . seemed to be “busy work,” leading nowhere. . . .

Thus, some women expressed certain regrets: “It is too late to develop a new skill leading to a career.” “If I had pursued a single line, it would have utilized my potential to the full.”

But the authors note with approval that “the vast majority have somehow adjusted themselves to their place in society.”

Because our culture demands of women certain renunciations of activity and limits her scope of participation in the stream of life, at this point being a woman would seem to be an advantage rather than a handicap. All her life, as a female, she had been encouraged to be sensitive to the feelings and needs of others. Her life, at strategic points, had required denials of self. She had had ample opportunities for “dress rehearsals” for this latest renunciation . . . of a long series of renunciations begun early in life. Her whole life as a woman had been giving her a skill which she was now free to use to the full without further preparation . . .

7. Nevitt Sanford, “Personality Development During the College Years,” Journal of Social Issues, 1956, Vol. 12, No. 4, p. 36.

8. The public flurry in the spring of 1962 over the sexual virginity of Vassar girls is a case in point. The real question, for the educator, would seem to me to be whether these girls were getting from their education the serious lifetime goals only education can give them. If they are, they can be trusted to be responsible for their sexual behavior. President Blanding indeed defied the mystique to say boldly that if girls are not in college for education, they should not be there at all. That her statement caused such an uproar is evidence of the extent of sex-directed education.

9. The impossibility of part-time study of medicine, science, and law, and of part-time graduate work in the top universities has kept many women of high ability from attempting it. But in 1962, the Harvard Graduate School of Education let down this barrier to encourage more able housewives to become teachers. A plan was also announced in New York to permit women doctors to do their psychiatric residencies and postgraduate work on a part-time basis, taking into account their maternal responsibilities.

10. Virginia L. Senders, “The Minnesota Plan for Women’s Continuing Education,” in “Unfinished Business—Continuing Education for Women,” The Educational Record, American Council on Education, October, 1961, pp. 10 ff.

11. Mary Bunting, “The Radcliffe Institute for Independent Study,” Ibid., pp. 19 ff. Radcliffe’s president reflects the feminine mystique when she deplores “the use the first college graduates made of their advanced educations. Too often and understandably, they became crusaders and reformers, passionate, fearless, articulate, but also, at times, loud. A stereotype of the educated women grew up in the popular mind and concurrently, a prejudice against both the stereotype and the education.” Similarly she states:

That we have not made any respectable attempt to meet the special educational needs of women in the past is the clearest possible evidence of the fact that our educational objectives have been geared exclusively to the vocational patterns of men. In changing that emphasis, however, our goal should not be to equip and encourage women to compete with men. . . . Women, because they are not generally the principal breadwinners, can be perhaps most useful as the trail blazers, working along the bypaths, doing the unusual job that men cannot afford to gamble on. There is always room on the fringes even when competition in the intellectual market places is keen.

That women use their education today primarily “on the fringes” is a result of the feminine mystique, and of the prejudices against women it masks; it is doubtful whether these remaining barriers will ever be overcome if even educators are going to discourage able women from becoming “crusaders and reformers, passionate, fearless, articulate,”—and loud enough to be heard.

12. Time, November, 1961. See also “Housewives at the $2 Window,” New York Times Magazine, April 1, 1962, which describes how babysitting services and “clinics” for suburban housewives are now being offered at the race tracks.

13. See remarks of State Assemblywoman Dorothy Bell Lawrence, Republican, of Manhattan, reported in the New York Times, May 8, 1962. The first woman to be elected a Republican district leader in New York City, she explained: “I was doing all the work, so I told the county chairman that I wanted to be chairman. He told me it was against the rules for a woman to hold the post, but then he changed the rules.” In the Democratic “reform” movement in New York, women are also beginning to assume leadership posts commensurate with their work, and the old segregated “ladies’ auxiliaries” and “women’s committees” are beginning to go.

14. Among more than a few women I interviewed who had, as the mystique advises, completely renounced their own ambitions to become wives and mothers, I noticed a repeated history of miscarriages. In several cases, only after the woman finally resumed the work she had given up, or went back to graduate school, was she able to carry to term the long-desired second or third child.

15. American women’s life expectancy—75 years—is the longest of women anywhere in the world. But as Myrdal and Klein point out in Women’s Two Roles, there is increasing recognition that, in human beings, chronological age differs from biological age: “at the chronological age of 70, the divergencies in biological age may be as wide as between the chronological ages of 50 and 90.” The new studies of aging in humans indicate that those who have the most education and who live the most complex and active lives, with deep interests and readiness for new experience and learning, do not get “old” in the sense that others do. A close study of 300 biographies (See Charlotte Buhler, “The Curve of Life as Studied in Biographies,” Journal of Applied Psychology, XIX, August, 1935, pp. 405 ff.) reveals that in the latter half of life, the person’s productivity becomes independent of his biological equipment, and, in fact, is often at a higher level than his biological efficiency—that is, if the person has emerged from biological living. Where “spiritual factors” dominated activity, the highest point of productivity came in the latter part of life; where “physical facts” were decisive in the life of an individual, the high point was reached earlier and the psychological curve was then more closely comparable to the biological. The study of educated women cited above revealed much less suffering at menopause than is considered “normal” in America today. Most of these women whose horizons had not been confined to physical housekeeping and their biological role, did not, in their fifties and sixties feel “old.” Many reported in surprise that they suffered much less discomfort at menopause than their mothers’ experience had led them to expect. Therese Benedek suggests (in “Climacterium: A Developmental Phase,” Psychoanalytical Quarterly, XIX, 1950, p. 1) that the lessened discomfort, and burst of creative energy many women now experience at menopause, is at least in part due to the “emancipation” of women. Kinsey’s figures seem to indicate that women who have by education been emancipated from purely biological living, experience the full peak of sexual fulfillment much later in life than had been expected, and in fact, continue to experience it through the forties and past menopause. Perhaps the best example of this phenomenon is Colette—that truly human, emancipated French woman who lived and loved and wrote with so little deference to her chronological age that she said on her eightieth birthday: “If only one were 58, because at that time one is still desired and full of hope for the future.”

Metamorphosis: TWO GENERATIONS LATER

1. New York Times, February 11, 1994. U.S. Census Bureau data compiled by F. Levy (MIT) and R. Murnane (Harvard).

2. “Women: The New Providers,” Whirlpool Foundation Study, by Families and Work Institute, May, 1995.

3. “Employment and Earnings,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, January, 1996.

4. U.S. Census Bureau data from current Population Reports, 1994.

5. National Committee on Pay Equity, compiled U.S. Census Bureau data from Current Population Reports, 1996.

6. “The wage Gap: Women’s and Men’s earnings,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 1996.

7. Washington Post, September 27, 1994. Data released from “Corporate Downsizing, Job Elimination, and Job Creation,” AMA Survey, 1994. Also The Downsizing of America: The New York Times Special Report. New York: Random House, 1996.

8. “Women’s Voices: Solutions for a New Economy,” Center for Policy Alternatives, 1992.

9. “Contraceptive Practice and Trends in Coital Frequency,” Princeton University Office of Population Research, Family Planning Perspectives, Vol. 12, No. 5, October, 1980.

10. Starting Right: How America Neglects Its Youngest Children and What We We Can Do About It, Sheila B. Kamerman and Alfred J. Kahn. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.