Part I

FIRST ST . PHILIP ’S CHURCH

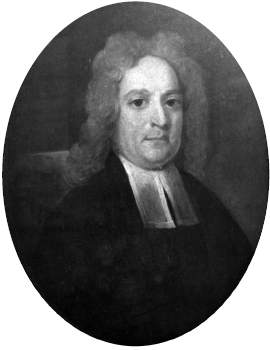

The Reverend Frederick Dalcho, MD. Engraving by A.B. Durand .

SETTING THE STAGE

This volume covers the first 180 years of St. Philip’s Church. As the state church, St. Philip’s not only attempted to meet the spiritual needs of the early settlers, but it was also responsible for civic leadership, including oversight of elections, education and social services covering everything from healthcare to disaster relief. The magnitude of its sphere of influence cannot be overstated.

In 1820, the Reverend Frederick Dalcho, MD, published An Historical Account of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South Carolina from the First Settlement of the Province, to the War of the Revolution; with Notices of the Present State of the Church in Each Parish; and Some Account of the Early Civil History of Carolina, Never Before Published. To Which Are Added; The Laws Relating to Religious Worship; the Journals and Rules of the Convention of South-Carolina; the Constitution and Canons of the Protestant Episcopal Church, and the Course of Ecclesiastical Studies: with an Index, and List of Subscribers . This was the first diocesan history recorded in the United States. It is considered the definitive history of the Episcopal Church in South Carolina and has been cited by numerous historians since its publication. 1

This volume has been patterned on Dalcho’s account of the first permanent settlement of the province and extends the history of St. Philip’s Church to 1860. (Please note that this work follows the custom of calling Charleston “Charles Town” in the period before the American Revolution.)

Although Dalcho served only temporarily at St. Philip’s, his life merits a brief examination. He was born in London in 1770, son of an officer who served under Frederick the Great. His father died while he was still a child; his mother operated an inn in London after his father’s death. Young Dalcho was sent to live with his uncle, Dr. Charles Frederick Wiesenthal, a Baltimore physician who provided him with a classical education.

Dalcho received a degree in medicine in 1790. Two years later, he became a surgeon’s mate in the United States Army in Savannah. He was briefly married to Eliza Vanderlocht, who died in April 1795. He resigned his army commission in the fall of that same year and began working as a ship’s surgeon. He later rejoined the army and, in 1799, completed his service duty at Fort Johnson on James Island, South Carolina. He settled in Charleston and went into practice with Dr. Isaac Auld. Within two years, he had been elected the sixty-sixth member of the South Carolina Medical Society. On Christmas Day 1805, he married Mary Elizabeth Threadcraft in St. Philip’s Church.

When Dalcho resigned from the medical society in 1809, it refused to accept his resignation and instead gave him an honorary membership. Dalcho became coeditor of the Charleston Courier , a Federalist daily newspaper, and also became a lay reader at St. Paul’s Stono.

He began to study theology in 1811. He attended the Diocesan Convention in 1815 and continued to serve at St. Paul’s Stono until he became the assistant minister of St. Paul’s Radcliffeborough in 1817. When Bishop Dehon died, Dalcho was asked to serve at St. Michael’s until the Reverend Nathaniel Bowen became rector in February 1818.

Dalcho was ordained a priest by Bishop White of Pennsylvania in June 1818. When Bishop Bowen’s duties became increasingly demanding, St. Michael’s elected Dalcho its assistant minister in 1819, a position he held until 1835.

Dalcho’s other passion was the Masons. He and John Mitchell opened the first Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite in America at Shepheard’s Tavern, located at the northeast corner of Broad and Church Streets. Dalcho delivered orations on the Masons at St. Michael’s Church in 1799, 1801 and 1803. The last, when published, included a history of Freemasonry in South Carolina. As a testimonial to his contributions to the Masons, the Grand Lodge of Ancient Freemasons of South Carolina passed a resolution to have his likeness put into future copies of Ahiman Rezon , his seminal book about the Masons.

In November 1836, Frederick Dalcho died at his Meeting Street home. He was buried in St. Michael’s Churchyard. The vestry erected a memorial tablet in his honor, but because of anti-Masonic feelings, it was placed outside the church. Years later, it was relocated to the west wall of St. Michael’s sanctuary.

The inscription on the tablet was written by Bishop Nathaniel Bowen. The latter portion reads, “Fidelity, industry, and Prudence, were the characteristics of his ministry. He loved the Church, delighted, to the last, in its service, and found in death, the solace & support of the Faith, which with exemplary constancy he had preached. Steadfast & uniform in his own peculiar convictions & action, as a member & minister of the P.E. Church, he lived & died in perfect Charity with all men.” 2

A friend wrote, “Dr. Dalcho was about 5½ feet in height, muscular and well proportioned. Having been accidentally wounded in the lungs, he became occasionally asthmatic, and his voice, naturally pleasant, was thus sometimes oppressed. His features were well marked, denoting a vigorous and well cultivated intellect, as well as a thoughtful and earnest spirit. His kind, amiable and genial disposition, his fine social qualities, his extensive information and liberal principles, made him a great and general favorite in the community.” 3

Reproduction of the Carolina Colony Seal of the Lords Proprietor. The front depicts a shield on which two cornucopias, filled with produce, are crossed. Supporting the shield are an Indian chief holding an arrow and an Indian woman with a child by her side and another in her arms. On top of the shield is a helmet, surrounded by a wreath with a mantle on which a stag stands. The Latin inscription below the crest reads Domitus cultoribus orbis , or “Tamed by the husbandmen (cultivators) of the world.” Circling the entire seal is written in Latin Magnum sigillum carolinæ dominorum , meaning “To dominate and conquer the world.” The reverse side depicts the eight heraldic shields of the Proprietors surrounding a Cross of St. George. This seal was used on all official papers of the Lords Proprietor. Only two documents survive with the seal intact; one is at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia, South Carolina.

SETTLEMENT OF CHARLES TOWN

To understand the settlement of the Carolina province, one must be aware of the upheavals that occurred in seventeenth-century England. Queen Elizabeth I was the last of the Tudor line. She died without issue in 1603, and the throne passed to her distant cousin James Stuart (King James VI of Scotland). James I was descended from the Tudors through his great-grandmother Margaret Tudor, eldest daughter of Henry VII. During James I’s reign, England enjoyed uninterrupted peace and comparatively low taxation. The country witnessed English colonization of North America, literature flourished and the king sponsored a translation of the Bible that bears the name “King James Version.”

Unfortunately, James I inculcated in his son Charles the idea of the divine right of kings and a disdain for Parliament, a lethal combination that culminated in Charles I’s death and the abolition of the monarchy. Charles I was beheaded for high treason in 1649, and his son, another Charles, fled to the continent.

After years of civil war, England became a republic ruled by the despotic Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. After Cromwell’s death in 1658, he was buried in Westminster Abbey. 4 His son Richard Cromwell succeeded him as Lord Protector, but lacking his father’s forceful personality, he was removed seven months later.

In 1660, Parliament asked Charles to return from exile, and he was crowned Charles II at Westminster Abbey on April 23, 1661. Afterward, the “Merry Monarch” began to reward his supporters, among whom were the Lords Proprietor of Carolina.

The Lords Proprietor

During England’s civil war, the tiny island of Barbados became an asylum for both Royalists (Cavaliers) and Parliamentarians (Roundheads, Cromwellians). They lived together amicably until King Charles I was beheaded. After his execution, a victorious Cromwell took revenge on the Barbadian Royalists. In 1651, the island was besieged, and when they surrendered, the Royalists were forced to sign “Articles of Capitulation” and submit to restrictive trade laws that prohibited colonial trade. Consequently, when the monarchy was restored, the Barbadian Royalists looked to the new king for reward for their loyalty and suffering.

One Royalist was John Colleton. During England’s civil war, he had served as a colonel under John Berkeley, Baron of Stratton, and after Cromwell’s forces succeeded, he fled to Barbados. When Charles II ascended to the throne, Colleton returned to London. Through Berkeley’s intervention, he was knighted and appointed to the Council on Foreign Plantations, where he came into contact with some of the most powerful men in the realm.

With his colonial experience, Colleton developed the idea of colonizing the vast wilderness located between Virginia and Spanish Florida. He enlisted the support of his influential kinsmen: George Monck, the Duke of Albemarle, and Lord Berkeley. Colleton later recruited Lord Chancellor Edward Hyde, the Earl of Clarendon; William Craven, the Earl of Craven; Anthony, Lord Ashley Cooper (later Earl of Shaftesbury); Sir George Carteret; and Sir William Berkeley.

In 1663, King Charles II granted them a Proprietary charter for the Province of Carolina. The paper empire covered both “Ecclesiastical and Civil” authority and included the lands south of Virginia to Spanish Florida, extending west to the Pacific Ocean. The king granted the Proprietors taxing and legislative powers, rights usually enjoyed by a ruling monarch. 5

In 1665, the Proprietors’ charter was ratified with another that extended the boundaries of the province and gave discretion in the matter of religious liberty. The Proprietors envisioned populating their holdings with experienced settlers from established colonies with promises of generous land grants and extremely liberal political and religious rights. They expected the colonists to bear the costs of colonizing and to compensate them through rents.

The newly knighted Barbadian Sir John Yeamans was recruited to establish a colony at Cape Fear. He was created a landgrave and given the right to forty-eight thousand acres of land. Yeamans had impressive credentials. He had owned land in Barbados since 1638. He had served as a colonel in the Royalist army, and after Charles I was beheaded, he immigrated to Barbados. Within ten years, he had become a large landholder and had served as a militia colonel, a judge and a member of the Barbados Council. 6

Yeamans promptly organized an expedition to establish a colony south of Virginia and to explore the territory of the new province. To raise money, a venture capital company called Adventurers for Carolina was organized in Barbados; members were to receive five hundred acres of land for every one thousand pounds of Muscovado sugar contributed.

Bad luck plagued the expedition. Yeamans sailed forth from Barbados in a flyboat (a boat with a shallow draft) accompanied by a small frigate of his own and a sloop purchased by the common purse. The vessels soon encountered rough weather and were separated. They managed to join up again at the mouth of the Charles (Cape Fear) River. The flyboat ran aground when it hit the treacherous shoals and breakers at the mouth of the river, and almost all the provisions and arms were swept away. This disaster caused Yeamans to abandon the original plans. He sent one of the remaining vessels to Virginia for supplies and returned to Barbados on the other ship, a decision that would come back to haunt him.

Yeamans sent a ship back to the expedition from Barbados with supplies. En route, the captain, Edward Stanton, became demented, leaped into the sea and was lost. Somehow the little vessel made it back, giving Captain Robert Sandford the means to undertake his voyage of discovery along the Carolina coast. He encountered the Kiawah Indians living around Edisto Island. Their friendly reception caused him to leave Henry Woodward behind to learn their language; in exchange, Sanford took the chief’s son with him to learn the ways of the white men and promised to return. In 1666, Sanford published A Relation of a Voyage on the Coast of the Province of Carolina , giving a detailed account of his voyage.

As for the Cape Fear colony, after numerous setbacks, it was abandoned in 1667. 7

Anthony Ashley Cooper Assumes Leadership

In the early years of the Proprietorship, John Colleton and his powerful cousin, George Monck, assumed leadership. Colleton died in 1666, and Albemarle retired from public life due to poor health. Then Edward Hyde fell from power and fled into exile in 1667. With their numbers depleted, it is not surprising that the remaining Proprietors lost interest in settling Carolina.

The venture was rescued by Anthony Ashley Cooper, an accomplished politician who had served on the Council of State for Plantations during the Interregnum and continued on after the Restoration. Lord Ashley was also a member of committees and councils dealing with colonies and had invested in overseas trading companies. Not yet the Earl of Shaftesbury, his career in early 1669 was approaching its peak.

Ashley persuaded the Proprietors to abandon their parsimonious colonial policies and assume some of the financial burden of establishing a colony. Each Proprietor agreed to contribute £500 sterling to start a new settlement and reluctantly pledged further contributions of £200 for four years to support the colony; they also agreed to recruit settlers from England.

Once he obtained the Proprietors’ agreement, Ashley moved quickly. Within three months, he had recruited more than one hundred prospective colonists, purchased and outfitted three ships (Carolina, Port Royal and Albemarle ) and appointed Captain Joseph West to command the expedition. The fleet was ready to sail in August 1669. 8

During the summer of 1669, Lord Ashley commissioned his friend John Locke to write a constitution for governing the colony. Although they expected the venture to be profitable, they drew up Fundamental Constitutions , which they believed would be the ultimate foundation for a perfect society—namely, an oligarchy ruled by a benevolent hierarchy of titled, wealthy, highly moral individuals who practiced the Anglican faith.

In Locke’s Fundamental Constitutions , the Proprietors delegated authority to their representatives and retained a veto power over their acts. The ruling colonial Grand Council consisted of a governor and Proprietary representatives, an upper house of ten colonials selected by the leading landowners and a Commons House of Assembly composed of twenty members selected by landed “freedmen” whose power was limited to the discussion of proposals from the other two parts of the Grand Council. The Fundamental Constitutions set up the division of the land, protected slavery and granted religious freedoms to non–Roman Catholic settlers. Colonists were given an opportunity to become titled landholders. Depending on one’s pocketbook, one might become a baron, cacique or landgrave. (The Charleston Library Society has an original copy of this document.) 9

The grand expedition got off to a poor start. The three ships left England and stopped to recruit servants in Kinsale, Ireland, where some of the passengers deserted the party. This delayed departure until mid-September. The ships finally reached Barbados in October and remained there until February. Already a landgrave, Sir John Yeamans named himself governor of the expedition. Before they set sail, a gale wrecked Albemarle on Barbados’s rocky coast; Yeamans hired Three Brothers as a replacement vessel.

The run to Carolina was a near disaster. The ships ran into a vicious storm and were scattered near the island of Nevis. Port Royal wrecked near Abaco in the Bahamas. Only Carolina and Three Brothers landed in Bermuda, where some of Port Royal ’s survivors managed to rejoin them.

While the ships were in Bermuda, Yeamans decided to leave the expedition, providing an excuse that was not well received by the other colonists. He persuaded William Sayle, the eighty-year-old former governor of Bermuda, to take his place.

On the voyage from Bermuda, another storm drove Three Brothers to Virginia. Only the two-hundred-ton frigate Carolina landed at Bull’s Island, located about thirty miles from present-day Charleston. The Proprietors had originally intended to establish a settlement in Port Royal; however, some Kiawah Indians met the landing party, and on the advice of the cacique, Carolina proceeded to a more protected location at Albemarle Point located on the west bank of the Ashley River, landing on March 15, 1670. 10 Although Spain, France and England had already attempted to colonize the Carolinas, this would prove to be the first permanent settlement.

The settlers landed, erected wooden fortifications and built homes. The colony’s business was conducted at this location until December 1679, when the Proprietors designated Oyster Point (Charleston), at the junction of the Cooper and Ashley Rivers, as the port town for the colony. Within a year, Albemarle Point was deserted. (All surface traces of the Albemarle settlement have since disappeared.) 11

Charles II’s 1663 charter proclaimed zeal “for the propagation of the Christian faith in a country not yet cultivated or planted, and only inhabited by some barbarous people, who had no knowledge of God.” 12 Evidently, this also applied to the condition of the first settlers because within three months of their arrival on June 25, Governor William Sayle wrote to England, requesting the services of Samson Bond, a Church of England clergyman then living in Bermuda.

Three months later, in September 1670, a second letter followed the first. This appeal was endorsed by Florence O’Sullivan, Stephen Bull, Joseph West, Ralph Marshall, Paul Smith, Samuel West and Joseph Dalton. The letter requested an able minister to instruct the people in the true religion, pointing out that “[t]he Israelites’ prosperity decayed when their prophets were wanting, for where the ark of God is, there is peace and tranquility.” 13 The Reverend Mr. Bond did not come in spite of the Proprietors’ enticing offer of five hundred acres of land and four pounds per annum. 14

Cassique of Kiawah by Willard Newman Hirsch. Photograph by Douglas M. Pinkerton .

As the province’s only landgrave, Sir John Yeamans finally arrived in 1671 fully expecting to become governor. He discovered that Governor Sayle had died and Joseph West had been appointed interim governor until the Lords Proprietor could appoint a replacement. West was a capable leader, and Yeamans became the third governor over the objections of members of the Grand Council, who decried both his desertion while the recent expedition was in Bermuda and his abandoning of the Cape Fear colony in 1665.

Yeamans arrived with two hundred African slaves and angered the settlers by sending much-needed lumber back to Barbados. He also angered Shaftesbury when he profited by selling provisions to Barbados instead of within the fledgling Carolina colony, where they were sorely needed. He was called a “sordid calculator” bent solely on acquiring a fortune. Yeamans was finally removed from office and died before news of his replacement by Joseph West arrived in Charles Town. Biographers have since described him as everything from a swashbuckling cavalier to a land pirate. 15

Oyster Point

The colonists soon discovered that Albemarle Point was inconvenient and unhealthy. One of the first official acts of Governor Yeamans was to issue an order for the “laying out of a town” at Oyster Point, a small peninsula located at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers.

John Coming, first mate of the Carolina and later captain of the Blessing , had received land grants on the Cooper River for his services as a sea captain. Coming and his partner, Lieutenant Henry Hughes, also took out grants for land at Oyster Point. In February 1672, John Coming, accompanied by his wife, Affra Harleston Coming, and Henry Hughes, appeared before the Grand Council and voluntarily surrendered half of their lands on Oyster Point for the townsite. Mr. Hughes’s land was retained by the Grand Council, while Coming’s was released. (Coming’s widow, Affra Harleston, later gave this land to St. Philip’s rector for his support.) 16

In 1680, a clerk aboard HMS Richmond published a description of the province. He depicted the town as “regularly laid out into large and capacious streets, which, to buildings, is a great ornament and beauty. In it they have reserved convenient places for a church, town house and other public structures, an artillery ground for the exercise of their militia, and wharves for the convenience of their trade and shipping.” 17

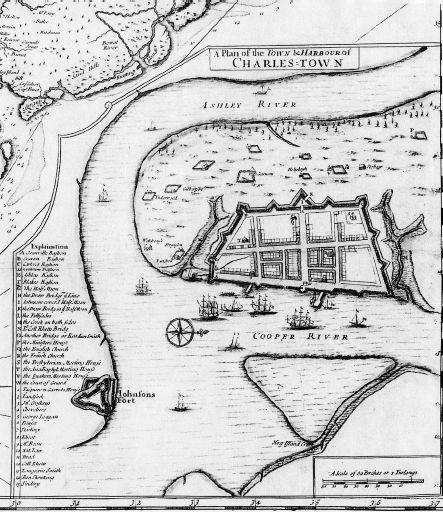

Detail from “A Plan of the Town & Harbor of Charles Town” insert for A Compleat Description of the Province of Carolina in 3 Parts by Edward Crisp, circa 1710. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

For protection, two great guns were mounted on Oyster Point; upon the appearance of any topsail vessel, one gun was to be fired, calling the settlers to appear bearing arms to defend the town. The colonists were enrolled in three companies, with the first commanded by the governor, the second by Lieutenant Colonel John Godfrey and the third by Captain Maurice Mathews. 18

John Godfrey, head of the second militia, was a Barbadian gentleman and merchant who had been a deputy in the Council. He was among the subscribers who underwrote William Hilton’s explorations of the Carolina coast and was eligible for five hundred acres. Yeamans persuaded him to settle in Carolina. Godfrey sailed on the John and Thomas in 1671. He was a member of the Grand Council in the early years of the colony and a lieutenant colonel in the militia that repelled the Spaniards in 1672. 19

Maurice Mathews, head of the third militia, was the nephew of two of the Earl of Shaftesbury’s friends. At one point, he was Shaftesbury’s deputy. Part of the original settlement, he was a passenger on Three Brothers when the sloop was blown off course and driven to the island of St. Catherine, Georgia, while en route to Carolina. Mathews remained on board while Captain John Rivers (Lord Ashley’s deputy) and several passengers went ashore for water. At the instigation of a Spanish friar living there, they were captured by the local Indians. The sloop managed to escape, but the unfortunate captives were imprisoned in St. Augustine, where they all died.

Mathews was a member of the Grand Council and eventually became the colony’s surveyor general. As the Fundamental Constitutions required that the whole province be surveyed, this was a position of great importance. Mathews surveyed land as far south as Florida. His work has been preserved in the Edward Crisp map of 1710. 20

The first group of colonists numbered 130, mostly English men and women; only a few were from Barbados. During the next two years, however, more than half of the new white settlers originated from Barbados. By the 1690s, more than 50 percent of the white settlers originated from the English West Indies. Regardless of their origins, these settlers were called “Barbadians.” 21

Their names dot the landscape, and many of their descendants still live in South Carolina:

From Barbados Proprietor Sir John Colleton; Governor James Colleton; Major Charles Colleton; Sir John Yeamans, Landgrave and Governor; Captain John Godfrey, Deputy; Christopher Portman, John Maverick, and Thomas Grey, among the first members elect to the Grand Council; Captain Gyles Hall, one of the first settlers and the owner of a lot in Old Town; Robert Daniel, Landgrave and Governor; Arthur and Edward Middleton, Benjamin and Robert Gibbes, Barnard Schinkingh, Charles Buttall, Richard Dearsley, and Alexander Skeene. Among others from Barbados were those of the following names: Cleland, Drayton, Elliot, Fenwicke, Foster, Fox, Gibbon, Hare, Hayden, Lake, Ladson, Moore, Strode, Thompson, Walter, and Woodward. Sayle, the first governor, was from Bermuda. From Jamaica came Amory, Parker, Parris, Pinckney, and Whaley; from Antigua, Lucas, Motte, and Percy; from St. Christopher, Rawlins and Lowndes; from the Leeward Islands: Sir Nathaniel Johnson, the Governor; and from the Bahamas: Nicholas Trott, the Chief Justice .

The Barbadian colonists brought with them the culture already established in the “sugar” islands, a slave-based economy that would ultimately destroy itself.

THE EARLY YEARS

First St. Philip’s Church

The first Anglican church in the new province was built about 1680–81 at the southeast corner of present-day Meeting and Broad Streets. It was the first land consecrated for a church and has remained consecrated to this day. The church was described as a “large and stately building” of black cypress on a brick foundation, surrounded by a white palisade fence. It was originally called the “English Church” or the Church of England. The name St. Philip’s appeared in a deed in 1697 conveying a lot of land on Broad Street. Historian Edward McCrady suggests that the first church was hastily built of unseasoned materials. 22

The original lot was not much deeper on Broad Street than the length of present-day St. Michael’s Church, which occupies the site today. In 1692, Robert Seabrooke was awarded Lot 159 next to the church. He sold it to William Popell in October 1696, a sale that apparently did not please the ruling powers of the colony because a scant two months later, “in pursuance of an order of the Assembly on December 5, 1696,” the western portion of the “Lott” (adjacent to the land reserved for the church) was deeded back to Governor Joseph Blake for a churchyard.

Acquiring the grounds was a complicated process. Popell received £10 sterling for this part of his holdings. 23 Popell died, and his widow, “Dorithy,” who inherited, found herself unable to pay the principal or interest of her £200 currency mortgage on the eastern portion of Lot 159 (long since divided into three lots). She had to sacrifice the property to Mary, wife of William Livingston. This transaction required another act of the Assembly because Mary Livingston died before the mortgage claim could be settled, and Livingston had already promised to sell the land and needed a clear title. The Assembly cleared title to the three lots in an act on December 12, 1712. The westernmost lot was later acquired by St. Michael’s Church and is now part of its churchyard. 24

The first Anglican rector was the Reverend Atkin Williamson, who is thought to have come as early as 1672. He was rector of the “English Church” (St. Philip’s) for thirty years. The only personal records available are the pitiful appeals to the General Assembly for financial assistance when he was sick and destitute at the end of his life. An act of 1710 appropriated thirty pounds per annum for his support. 25

Things could not have been easy for him. In a letter to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) in 1710, Commissary Gideon Johnston wrote that Williamson had lived in the province for twenty-nine years but had no credentials, and Johnston asked the SPG to check on his authenticity as an ordained Anglican. This inquiry may have been precipitated by a story that pranksters, knowing Williamson had a problem with strong drink, conspired to get him intoxicated, whereupon they presented a baby bear that he obligingly christened. Landgrave Thomas Smith wrote that some wicked people “got him to christen the bear” on Broad Street while in an inebriated condition. 26 The story of the christened bear continues to this day.

Samuel Marshall

There does not appear to have been a minister officiating at the English Church in 1696, when the Reverend Samuel Marshall was appointed to the cure. He had been recommended by the bishop of London and the Lords Proprietor as a sober, worthy, able and learned divine who left “considerable benefice and honorable way of living in England to come out to Carolina.” His income from the church was precarious. In 1698, the General Assembly passed an act giving him a salary of £150 per annum, a “Negro man and woman,” plus four cows and calves, all to be paid out of the public treasury. 27

In December 1698, Mrs. Affra Coming, widow of John Coming, made a donation of seventeen acres of land then adjoining the town to Mr. Marshall and his successors. Known as the Glebe (land for the support a parish priest), it was bounded by present-day Wentworth, Coming, Beaufain and St. Philip Streets. 28 That same year, a disastrous fire destroyed one-fourth of the city, pirates attacked shipping and a severe hurricane did much additional damage.

In 1699, yellow fever broke out. Marshall contracted the disease while helping the sick and died in an epidemic that took 160 lives. 29 Samuel Marshall was mourned as a sober and devout man who gave no “advantage to the enemies of our Church to speak ill of its Ministers.”

IN MEMORY OF AFFRA HARLESTON COMING

WHO EPITOMIZES THE COURAGE OF THE WOMEN WHO PIONEERED THE SETTLING OF THIS STATE, COMING BY HERSELF FROM ENGLAND IN 1670 AS A BONDED SERVANT AND SERVING A TWO YEAR INDENTURE TO PAY FOR HER PASSAGE . SHE AFTERWARDS MARRIED JOHN COMING, FIRST MATE OF THE SHIP CAROLINA .

WHILE HER HUSBAND WAS AT SEA , AFFRA, DESPITE DANGERS FROM DISEASE AND OFTEN HOSTILE INDIANS, CLEARED LANDS, PLANTED CROPS, AND MANAGED A REMOTE PLANTATION .

IN 1690, AFTER CAPTAIN COMING ’S DEATH , AFFRA DEEDED SEVENTEEN ACRES OF HER CHARLESTON LANDS TO THE RECTOR OF ST . PHILIP ’S EPISCOPAL CHURCH AND HIS SUCCESSORS “IN CONSIDERATION OF THE LOVE AND DUTY I HAVE, OWE TO THE CHURCH …TO PROMOTE AND ENCOURAGE…GOOD CHARITABLE, AND PIOUS…WORK.” SHE DIED NOT LONG AFTERWARDS .

THE GLEBE, SURROUNDED BY ST . PHILIPS , COMING , GEORGE AND BEAUFAIN STREETS, IS A LIVING REMINDER OF THE VISION AND CHARACTER OF CAROLINA ’S FIRST SETTLERS .

ERECTED (ON GLEBE STREET ) BY THE SOCIETY OF FIRST FAMILIES OF SOUTH CAROLINA 1670–1700

Marshall was a man of integrity and wisdom, and Council requested another Church of England minister with a similar exemplary character. To encourage a suitable successor, the Assembly passed an act that settled the same generous provisions on Marshall’s replacement: “£150 yearly, a good brick house and plantation, two negro slaves, and a stock of cattle, besides christening, marriage, and burial fees.” 30

Changes in Leadership

To populate the colony quickly, the Lords Proprietor had encouraged settlers of all religious faiths, except Roman Catholics. The 1669 charter granted liberty of conscience to “Jews, Heathen, and Dissenters.” “Dissenters” (those who were not Church of England Protestants) included Baptists, French Huguenot Calvinists, Quakers, Presbyterians and Puritans. Within ten years of settling the province, the population was composed of 40 percent Englishmen, 40 percent Dissenters and 20 percent uncommitted. By 1695, one Jew is on record as living in Charles Town.

Governor Joseph Blake died in 1700. His sister was the wife of ex-governor Joseph Morton Jr. Morton had already been governor twice. He was the senior resident landgrave, and the Council elected him as Blake’s replacement. Morton was a moderate who was influential in the recruitment of religious Dissenters to the new colony. Chief Justice James Moore 31 protested Morton’s election because he already held a royal commission as judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court and, therefore, was ineligible to be governor. The Council concurred, reversed itself and elected Moore to fill the vacancy.

This election signaled a change in government policy. The new governor was an Anglican and the acknowledged leader of the powerful “Goose Creek” faction. The Dissenters, who had been in control of provincial politics for many years, did everything they could to destroy Moore politically. 32 By the time Sir Nathaniel Johnson arrived with his commission as governor in March 1703, animosity between the Anglicans and Dissenters had become so great that leading Dissenters and their supporters were attacked or threatened in the streets of Charles Town. 33

Sectarian Controversy

Governor Nathaniel Johnson was a High Church Anglican. He supported Church of England settlers and looked on Dissenters of every denomination as enemies to the constitutions of both church and state. He immediately dissolved the Sixth Assembly and called for a new election. Somehow notice of a special session reached only the Berkeley and Craven County delegations, the areas where the Anglican settlers lived. They met in May 1704 and passed an act excluding those who did not conform to the worship of the Church of England from participation in the Assembly. In the Lower House, the act passed by a one-vote margin, and in the upper house, Landgrave and former governor Joseph Morton was refused liberty to enter his protest. In November, the General Assembly passed the Establishment Act, making the Church of England the state church. Ministers’ salaries and church construction were to be financed by an export and import tax; local vestries were empowered to raise revenue by assessing real and personal property. The act gave the laity control over the church. Taxpaying parishioners were to select the rector and the vestry. A lay commission would oversee the church at large, with the power to remove ministers. 34

Governor Sir Nathaniel Johnson , dated 1705, by unidentified artist, oil on canvas. © Image courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association, 1997.006.0001 .

When the Dissenters challenged the act, their leaders were ousted from office, most notably the public receiver, Landgrave Thomas Smith. The act was so abhorrent that the next Assembly voted to repeal the law, but Governor Johnson refused to sign the repeal.

The Dissenters tried to send John Ash, one of the most vigorous opponents, to London to plead their case. When the governor and his friends learned of Ash’s plans, they prevented him from obtaining passage on any ship sailing from Carolina. Ash was forced to go to Virginia to book passage for England. He died in England before completing his mission. 35

After Ash’s death, Joseph Boone was sent to London and presented his case to the House of Lords. He presented another petition to the Lords Proprietor charging Governor Johnson with crimes against the very foundations of the province. Boone engaged Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe , to highlight the plight of the Dissenters in several widely circulated pamphlets. 36

At first, the Proprietors ignored the plight of the Dissenters, but the House of Lords condemned the election of 1703 as fraudulent and the Exclusion and Church Acts as repugnant to the laws of England. Queen Anne referred the laws to the Lords of Trade, which argued that the Carolina Assembly had abused its powers and recommended that the charter of the colony be forfeited. The queen ordered the Proprietors to declare both acts void.

In 1705, the Commons House repealed the Exclusion Act, and Governor Johnson promptly dissolved the Assembly. The following year, a new Commons House was elected, with Anglicans in a clear majority. They met in November, repealed both acts and passed a new Church Act.

The Church Act of 1706 limited the boundaries of the urban parish and established nine new parishes: Christ Church, St. Thomas, St. John Berkeley, St. James Goose Creek, St. Andrew, St. Denis (Dennis), St. Paul Stono, St. Bartholomew and St. James Santee. Six were named after those in Barbados. 37 Six country parish churches were created, to be financed by income from the taxes on skins and furs. Treasury funds were appropriated for building churches and parsonages, purchase of Glebe lands and ministers’ salaries. 38

Sir Nathaniel Johnson’s high-handed intolerance caused such a riotous condition that his powerful enemies were able to have him removed from office in 1709. He retired to his plantation on the Cooper River and died there in 1712. He was buried at Silk Hope in a small walled-in enclosure in a grave that is unmarked today. 39 (The colony’s religious factionalism continued until Charles Craven, who supported toleration, became governor in 1712.)

When Governor Edward Tynte died in 1710, Chief Justice Robert Gibbes was appointed by Council to succeed him. Gibbes was born in England and immigrated to Barbados. 40 In August 1672, he landed in Carolina aboard the Loyal Jamaica , “a ship commonly called the Privateer Vessel” because all the passengers were placed under bond. 41 He was accompanied by several persons and slaves and received warrants for 630 acres. By 1709, he had received warrants for an additional 3,658 acres (1,866 acres due to his bringing in numerous slaves) and had acquired three lots in Charles Town.

Gibbes’s connections with the Proprietors explain his rise to political prominence. He was made a member of the General Assembly from Colleton County the year of his arrival. In 1683, he was commissioned sheriff of Berkeley County, and by 1698, he had advanced to colonel in the militia. In 1700, he was resident of a plantation located between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers in Berkeley County. In 1708, the Proprietors appointed him chief justice of South Carolina; Gibbes also served on numerous commissions. 42

According to the Fundamental Constitutions , only a duly appointed deputy could assume the governorship until the Proprietors selected a successor. When Governor Tynte died, only three eligible candidates were living in the province: Chief Justice Robert Gibbes; Thomas Broughton, son-in-law of Governor Sir Nathaniel Johnson; and Fortesque Turbeville, lately arrived deputy of the Duke of Beaufort. 43

The deputies met, voted and then recessed until the afternoon. When they reconvened, Gibbes was proclaimed governor. Because it was later discovered that Broughton had received a two-to-one vote in the morning, Gibbes was thought to have bribed Turbeville to change his vote during the recess. When Turbeville died shortly thereafter, people claimed that he had been poisoned.

Broughton was a candidate with a checkered past. He had married Sir Nathaniel Johnson’s daughter prior to emigrating from the West Indies in the 1690s. He served in the Commons House of Assembly from 1696 to 1703. After Sir Nathaniel received a commission to be governor of Carolina in 1702, Broughton tried to secure a monopoly in the profitable Indian trade in return for an annual payment of £800 sterling to the colony. Although the Assembly declined his offer, Broughton continued his attempts to dominate the Indian trade. In 1708, he was prosecuted by Thomas Nairne, the Indian agent, on charges that he had enslaved friendly Cherokees and misappropriated one thousand deerskins belonging to the province. Governor Johnson used his influence to have his son-in-law acquitted and had Nairne arrested for treason on dubious charges.

Broughton used his privileged position to obtain the lucrative office of surveyor general in 1707. He invested his profits in land and acquired 4,228 acres on the western branch of the Cooper River. In 1714, he built Mulberry Castle on land that had been granted to Proprietor Sir Peter Colleton. His son and heir, Sir John Colleton, discovered the trespass and made Broughton exchange three hundred acres plus pay £150 to secure ownership of the residence and site on which Mulberry Castle had been built (illegally). 44

At the time of Governor Tynte’s death, Broughton was a major general in the militia. Incensed at losing the election, he collected his supporters and marched to Charles Town. Gibbes, who resided in town, heard of their approach and had the drawbridge hauled up, giving the militia strict orders not to fire. Broughton’s supporters within the town and sailors from vessels in the harbor began to assemble to force down the drawbridge. After a scuffle, the drawbridge was finally lowered, and Broughton’s followers proceeded to the Watch House at the far end of Broad Street. Broughton’s party halted, and one of them drew a paper from his pocket. The man tried to read it, but the town militia made such a tremendous uproar with their drums that not a syllable of the proclamation could be heard over the racket.

Broughton’s men proceeded toward “Granville’s bastion,” escorted by sailors who were ready for any sort of mischief. As they passed the front of the armed militia, a sailor snatched the colors from the staff. Upon this provocation, a few of the militia, without any orders, fired their pieces. Nobody was hurt.

Broughton’s supporters continued about the town proclaiming him governor. Hurrahing as loudly as possible and making various other noises, they approached the gate of the town fort and made a show of forcing it. Armed militia, with their guns presented, stopped them. This cooled down the hotheads, who soon withdrew to a tavern on the Bay to read the proclamation once again. Thus ended a rowdy confrontation that had taken on all the aspects of a theatrical farce. 45

With such inglorious beginnings, during the early months of Gibbes’s administration, the Assembly refused to form a quorum in protest of the irregularity of his election. The Proprietors declared Gibbes’s election illegal because of bribery and refused to pay his salary. They chose neither contender as governor, appointing Charles Craven instead.

History might have given Governor Gibbes a bad reputation. Turbeville was new to the colony, and during the voting recess, the chief justice may have acquainted him with some of Broughton’s rather unsavory business practices. Turbeville’s subsequent death may have been coincidental, as many newcomers did not adjust well to the colony’s climate, and some died of an unknown malady known as “strangers” fever. Before leaving office, Governor Gibbes cited his administration’s accomplishments as encouraging white immigration to counteract the growing slave population, the quarantine of smallpox victims and the Free School Act. 46 His administration was marked by “wise enactment and undisturbed prosperity of the people.” 47

As for Thomas Broughton, he became lieutenant governor in 1735 upon the death of his brother-in-law, Governor Robert Johnson. According to historian Walter Edgar, Broughton’s administration was marked by “dissention and internal discord” for numerous reasons. Broughton died in 1737 and was survived by seven children, one of whom married John Gibbes, son of his former gubernatorial rival. 48

Ecclesiastical and Secular Responsibilities of St. Philip Parish

The parish system placed a heavy burden on the vestries and churchwardens at St. Philip’s. There are no parochial records before 1720, but indigents, strangers, the stranded, bereaved, deserted and betrayed are all listed in the registry. The parish church also collected fines for a wide range of offenses.

In 1712, an act was passed “for the better observation of the Lord’s Day, commonly called Sunday.” It required all persons to abstain from labor, selling goods, indulging in sports or pastimes or traveling on the Sabbath, except going to a place of religious worship or visiting the sick. Within Charles Town, it was the duty of St. Philip’s constables and churchwardens to patrol the streets in the forenoon and in the afternoon and observe, suppress and apprehend all offenders. 49

One of the duties of the vestry was collecting taxes for the care of the poor. As early as 1725, there is record of payments for medical relief for indigent outpatients. By 1734, it was recognized that a hospital was needed. In 1736, an act authorized building a “Proper Workhouse and Hospital.” Parish doctors were in much demand, and several prominent physicians were hired. Unfortunately, the workhouse-hospital was so poorly managed that the ill poor preferred begging on the streets to taking relief at the hospital.

The importation of slaves increased the incidence of illnesses and necessitated building a “pest house” on Sullivan’s Island to quarantine newcomers.

In June 1749, an act was passed directing, at public expense, that the wardens and vestry of St. Philip’s obtain a house for a public hospital for sick sailors and other transients. By 1750, there were two public hospitals in the city. 50

From 1716 until the Revolution, all elections in Charles Town were held at St. Philip’s. An eligible voter had to be a twenty-one-year-old white male who owned at least fifty acres of land or owned ten pounds in personal property and had a residence of three months prior to the date of the election. Elections by ballot were held for two days. To prevent voter fraud, names were entered into a book managed by the churchwardens. 51

With no municipal government in Charles Town before the Revolution, the General Assembly passed acts relating to streets, police and other ordinances usually delegated to city government. One of the most important municipal responsibilities was levying and collecting taxes for support of the parish indigent. This was a heavy duty for St. Philip’s vestry.

The clergy enforced laws; punishment for infringement was administered through the pillory, stocks, whippings, burnings in the hand and even burning at the stake. Bastardy was a terrible crime, and upon conviction, the accused were subject to imprisonment and fines. After a third offence, a woman taken in adultery could be tied to the back of a cart and whipped as she was jerked along the streets; she was also fined, as was her lover if he could be found. If there were a child, he or she could inherit only £100 at the death of the father.

In short, life in early Charles Town was controlled by the church and was quite harsh. In addition to an alien climate and natural disasters, settlers had to adjust to new food, bad water, lack of salt and any number of illnesses. Livestock roamed free beside fat pigs rooting in the streets and alleys. Superstitions abounded, and the civil liberties created one hundred years later by the Bill of Rights were nonexistent. 52

Education

In 1700, the estimated population of the province was about 5,500 white people, plus Indians and black residents, with only one minister located in the area outside Charles Town, the Reverend William Corbin. Few of the first settlers brought wives and children with them, but by the end of the century, the number of children born in the province had created a demand for schools and religious instruction. The population was growing rapidly, and church authorities began to recognize the need for more clergymen and schoolmasters. Those who could afford it hired private tutors. 53

The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) was founded in 1698. The primary concern was to counteract the growth of “vice and immorality,” which it ascribed to “gross ignorance of the principles of the Christian religion.” Members felt that the situation could be tackled through encouraging education and the production and distribution of Christian literature.

Thomas Bray 54 was one of the SPCK founders. By the time of his death, Bray had succeeded in establishing thirty-nine libraries in America. One of his religious libraries was given to St. Philip’s Church, and it is mentioned in the letters of the commissaries.

By 1700, a free public library had been established in Charles Town, and in 1710, the Assembly passed an act that authorized funding a free school. An appeal was made to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) to assist in its establishment. During the Church Act controversies, the SPG refused to send additional ministers to Carolina.

In 1712, under the administration of Governor Robert Gibbes, 55 the Assembly passed an Act of Incorporation authorizing a free school in Charles Town. A brick building was authorized for the school, and the Assembly appropriated a £100 annual salary for the master, who was required to teach Latin and Greek as well as the Church of England principles of religion. 56 The SPG placed the school under the care of the Reverend William Guy, who arrived in July 1712 with the charge to take special care of the scholars’ manners, both in and out of school, as well as teach the scholars to abhor lying and evil speaking. The need at St. Philip’s was so great, however, that Guy gave up his position as schoolmaster. Thomas Morritt succeeded him at the school. 57

Seal of the Society for Propagating the Gospel in Foreign Parts (1701).

SOCIETY FOR THE PROPAGATION OF THE GOSPEL IN FOREIGN PARTS

In 1696, Bishop of London Henry Compton appointed Thomas Bray a commissary to organize the Church of England in Maryland. Before Bray left England, a group of five friends met to prepare for his departure. Not knowing how long he would be away, the friends resolved to form a society to ensure that his many good works could continue in his absence. Out of that vision grew the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) in 1698.

In 1700, Thomas Bray persuaded Bishop Compton and Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Tenison that a society was needed to sponsor clergy for the colonies. In June 1701, William III granted a charter for the Society for Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. Its purpose was to receive contributions to spread the gospel and further education in the British colonies.

The charter had an auspicious membership: both archbishops, the bishops of London and Ely, the deans of Westminster and St. Paul’s, the archdeacon of London and the Regius and Lady Margaret Professors of Divinity of Oxford and Cambridge Universities, thus establishing the support of the officials of the Church of England and the universities. 58

Better known as the SPG or the Society, this privately sponsored, church-supported organization had lasting results in the colonies. The Society sent out hundreds of clergymen to all of the king’s dominions, especially North America. It required detailed reports from its ministers, and these reports have provided an invaluable source of historical and cultural material for historians.

The Society set high standards for its missionaries. The first requirement was to “keep in view the great design of their undertaking to promote the Glory of Almighty God and the Salvation of Men, by propagating the Gospel of our Lord and Savior.” Missionaries were expected to be thoroughly acquainted with the Doctrine of the Church of England as contained in the Articles, Homilies, Worship and Discipline , as well as rules for the behavior of the clergy, among many other specifics (e.g., their conduct under controversy, their apparel, their conversations and the idea that they may be “Instance and Patterns of the Christian Life”). To these lofty qualifications were additional instructions for frequent, fervent prayers; contemplation on the holy scriptures; reflection on their ordination vows; and consideration of the account that they are to render to the “great Shepherd and Bishop of our Souls at the last day.” 59

The powerful Judge Nicholas Trott, thought to be the first lawyer in the Carolina colony, was admitted to the SPG in 1702. He was a committed Anglican and published for the SPG The Laws of the British Plantations in America Relating to the Church and Clergy, Religion and Learning .

Samuel Thomas

The first missionary sent to Carolina by the SPG was the Reverend Samuel Thomas from Ballydon, near Sudbury, on the border of Essex and Suffolk Counties. He was thirty years old, with a wife and family of small children. His wife’s name was Elizabeth, but few details about her have survived.

Thomas’s voyage was a difficult one, and his letters reveal many minute details. The Society was a fledgling organization at the time, and Thomas had only a small budget. He began to worry about finances even before he left England. His ship sailed from London and made stops along the English coast, hoping to collect more settlers for the colony.

Thomas’s first letter was written from Rye, where he mentions having seen his brother. He described the ship as a leaky vessel, without convoy or cannons to protect them, in spite of the fact that England was at war with France and Spain and any British property on land or sea was fair game for privateers. The ship’s captain was a mean, surly fellow who did not provide Thomas a berth in spite of his having paid ten pounds for the passage. He was required to sleep on top of a box on the deck. The captain did not permit him to celebrate religious services for the frightened passengers. Thomas was ill during the voyage. After twelve weeks and two days at sea, in September 1702, the leaky vessel arrived at Portsmouth, Massachusetts. By then, Thomas was so sick that he was forced to seek medical treatment ashore. The unanticipated expenses of procuring a nurse and physician greatly depleted his already meager funds.

When his health returned, Thomas sailed for Charles Town, arriving on December 24, 1702. Governor Nathaniel Johnson suggested that Thomas serve the settlers in the Cooper River area rather than attempt to convert the “wild Indians,” as the Society had instructed. Thomas wrote to the SPG:

Now that I am here it hath pleased God to incline Sir Nathaniel Johnson to be very kind to me. He hath taken me into his house and his family is very large, many servants and slaves among whom I have a prospect of doing much good by God’s assistance. The neighborhood here to whom I preach every Lord’s day by Sir Nathaniel’s direction, are an ignorant but well inclined people, who seem to want nothing to make them truly pious but the common assistance of God’s Holy Spirit, Ministers & Ordinances. There are many Anabaptists in these parts, there being Preachers of that sort here, chuse [sic] rather to hear them than none. I have here a number of ignorant persons to instruct, too many profane to awaken, some few too pious to build up, and many Negroes, Indians to begin withal. I humbly beg your fervent prayers to God to direct and assist me in all difficulties. If the corporation would be pleased to send a few Bibles and Common Prayer books to give to the poor Negroes, I think it would be a most laudable charity…Sir Nathaniel hath promised to send for some of the chief Yemassee Indians…and if Sir Nathaniel find that the instructing them in the principles of Christian religion be practicable, he will order me among them . 60

Thomas’s labors were successful. Upon his arrival, there were only five communicants, and by his efforts, they increased to thirty-two. He also devoted time to the instruction of “Negroes” and taught twenty to read. His work at Goose Creek drew the wrath of the Reverend Edward Marston, the fiery Jacobite rector of St. Philip’s Church. Marston sent vehement complaints to the SPG in London, charging Thomas with dereliction of duty for not attempting to convert the Indians. He also charged that Thomas should not receive full salary because Governor Johnson was housing him.

Thomas was recalled to England to defend his actions at the end of his three-year assignment. He presented the Society a long brief, which gave it insight into the state of affairs in the colony; the meager salaries, which failed to attract more Anglican missionaries; the frontier conditions; the lack of religious practice among the English colonists; and his inability to minister to three scattered, small congregations. He also told of his accomplishments in spite of the many difficulties and begged the Society to send another minister to the Goose Creek area, “where the best men are.” 61

After he had signed with the SPG for another three-year stay, Thomas returned to the province. He landed in Charles Town in the midst of a raging smallpox epidemic in October 1705. He died before he ever returned to Goose Creek.

On June 20, 1706, Elizabeth Thomas presented the Society with a vivid account of her sad farewell as she watched her husband sail away, never to see him again. Their friends had loaded all their worldly goods on the ship and waited for the good sailing weather. She was pregnant at the time and so far gone with child that she could not join him on the long transatlantic voyage. She was left destitute, and her petition for relief was poignant:

Your Petitioner’s husband (with the Goods so on board) in obedience to the Society’s commands went the first opportunity to the place assigned without your Petitioner, which was an occasion to great sorrow to both and of great loss to your Petitioner and her children who intended to follow. Your Missionary (your Petitioner’s husband) died on his Cure in the service of the Society in October last of a pestilential fever raging there, caught (as your Petitioner is informed) by his frequent visitation of the sick, to the great sorrow and grief of your Petitioner, and the insupportable loss of herself and five small children who are left without any support or substance, but the charity of good people . 62

Little is known about the subsequent history of Elizabeth Thomas. Her son, Edward, came to South Carolina after the death of his father and claimed his estate, which included three hundred acres on the eastern branch of the Cooper River that had been granted to Thomas in 1702. The Reverend Samuel Thomas has many descendants in South Carolina, among them Bishop Albert Thomas and his brother, the Reverend Harold Thomas, as well as local lawyers, physicians and businessmen. Bishop Thomas was the author of The Episcopal Church in South Carolina, 1820–1957 .

Shortly after Samuel Thomas’s death, the Reverend Francis LeJau arrived at Goose Creek Parish to continue the good works that Thomas had begun.

The Reverend Doctor Francis LeJau

Francis LeJau, a native of Angiers, France, spent the first twenty years of his life in the La Rochelle (Protestant) region. After revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, he fled to England. LeJau married Jane Antoine Huguenin on April 19, 1691. He embraced Anglicanism and received from Trinity College, Dublin, an MA degree in 1693, a BD degree in 1696 and a Doctor of Divinity in 1700. He was a canon at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London when he decided to immigrate to the West Indies for health reasons.

In 1700, Bishop Henry Compton of London sent LeJau as rector of the three parishes of St. Christopher in the British West Indies. He was promised sixty pounds per annum, but the settlers did not deliver and provided only a house built with wild canes and an unfinished thatch roof, as well as two small cane-thatched church buildings. Over the opposition of the white settlers, LeJau also ministered to two thousand slaves in the three parishes. 63

The Reverend Doctor Francis LeJau (1665–1718), by Henrietta de Beaulieu Dering Johnston (American, circa 1674–1729), pastel on paper. Courtesy of the Margaret Simons Middleton Papers at the Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, South Carolina .

LeJau spent the next eighteen months in the West Indies. In 1705, the SPG accepted him as a missionary. When the call came for ministers at the eight new Anglican parishes in Carolina, LeJau responded immediately. He sailed from Plymouth, England, on the Greenwich , leaving his family behind. After a five-month voyage, his ship finally landed in Virginia. It was late 1706 when LeJau finally arrived in Charles Town. Governor Johnson and Chief Justice Nicholas Trott received LeJau into the Anglican fold. In 1707, he was assigned to St. James Goose Creek Parish. By then, the parish had one hundred families, most of whom belonged to the Church of England. After he was elected rector, LeJau’s parishioners lost no time in building a small church and parsonage. In his first letter to the SPG, LeJau requested that the Society assist his family in coming to Carolina, and they arrived in July 1707.

LeJau was determined to win all of the colony’s inhabitants to Christianity—white, black and Indian. He said of the Indians, “They make us ashamed by their life, Conversation, and Sense of Religion quite different from ours; ours consists in words and appearance, theirs in reality.” 64 On Sundays, he held special services for slaves and Indians and encouraged the slaves to maintain family fidelity. He ran a school in his home where he taught slaves to read and prepared them for baptism and communion, something that his white parishioners opposed.

As a slave owner, LeJau accepted the institution and justified it on scriptural grounds. He required slaves to publicly swear that they did not desire baptism out of some attempt to get free but only for the salvation of their souls. LeJau also worked for more humane treatment of slaves and denounced a law that permitted mutilation of runaway slaves. LeJau is credited with converting a greater number of black residents than any other SPG missionary, including those in Asia but excluding Siberia and the Philippines.

LeJau’s success was outstanding. His zeal gained the affection of his parishioners. They subscribed sixty pounds per year for his support in addition to his salary from the Society. His congregation soon outgrew its church and erected a new building; Captain Benjamin Schenckingh donated one hundred acres of land as a Glebe for St. James Goose Creek.

Next to Commissary Gideon Johnston, LeJau became the most influential Anglican clergyman in the province. When Johnston left for England, LeJau served at St. Philip’s Church and acted as the commissary’s deputy. 65 In 1715, while his son fought against the Yemassee during the uprising, LeJau and his family took refuge in Charles Town and lived in the parsonage with Henrietta Johnston and her family. LeJau’s account of the uprising is recorded in the The Carolina Chronicle of Dr. Francis LeJau, 1706–1717 by Frank J. Klingberg.

LeJau was taken sick in 1717 and died on September 15, 1718. He did not live long enough to learn that he had been appointed commissary after the death of Gideon Johnston. LeJau was buried at the foot of the altar at St. James Goose Creek. 66

William Guy

William Guy was ordained a deacon by Dr. John Robinson, bishop of London, on January 18, 1711. He was appointed to the dual offices of assistant minister at St. Philip’s Church and schoolmaster. The needs of the church were so great, however, that Guy gave up his position as schoolmaster and served as associate to Commissary Johnston.

The General Assembly established St. Helena Parish in June 1712, and the parishioners elected William Guy their minister. The parish of St. Helena included the lands occupied by the Yemassee Indians. No church had been built, and services were held in the homes of the planters. In January 1713, Guy returned to England, where he was ordained a priest by the bishop of London and officially appointed missionary to St. Helena’s. Guy returned to Carolina in May 1714.

When the Yemassee War broke out, Guy escaped the massacre and fled to Charles Town in a canoe with another white man and three slaves. Guy lost his horse and left all his possessions behind except his clothes, a Bible and a Book of Common Prayer that he had brought from London.

Guy informed the SPG of the desolation of his parish and suggested that it send him to a church in Bristol, Pennsylvania, where he had relatives. Commissary Johnston wrote the SPG that Guy could be used at St. Andrew Parish near Charles Town. On November 23, Governor Robert Daniell and members of Council petitioned the SPG to have Guy remain at St. Philip’s to replace the recently deceased John Whiteside. The SPG insisted upon sending Guy to Rhode Island, but his stay in New England was short.

Accompanied by his family, Guy returned to Carolina in November 1718. While his vessel waited outside the harbor, Guy was among those who sailed to town to engage a pilot to navigate the bar. During their absence, the ship was captured by pirates. It was returned three days later, but all of Guy’s possessions had been stolen. (While this was happening, Rebecca Guy’s cousin Thomas Hepworth, later chief justice, was one of the prosecuting lawyers at the trials of Stede Bonnet and his fellow pirates.)

Guy became rector of St. Andrew Parish in April 1719 and served there until his death in 1751. William Guy was an effective and much-loved clergyman and is considered one of the most accomplished ministers sent by the SPG. 67

EDWARD MARSTON

Prior to learning of the death of the Reverend Samuel Marshall in 1699, the Proprietors had secured the services of the Reverend Edward Marston 68 for Pompion Hill, a Chapel of Ease located on the east bank of the Cooper River. At that time, it was the only English church located outside of Charles Town and was attended by settlers from the Santee and nearby Goose Creek plantations.

In 1700, Marston arrived in Charles Town bearing impressive recommendations from the archbishop of Canterbury and the bishop of London. Instead of being sent to Goose Creek, Marston was given the vacant pulpit at St. Philip’s Church, where he preached two sermons every Sunday in addition to special occasions and served communion six times per year. He married not long after his arrival and soon had a family of three young children. He taught Latin to the children of Charles Town’s elite and prided himself on his scholarly bent.

Landgrave Thomas Smith called him a “man of Good life and conversation.” In the spring of 1702, the governor, Council and Assembly attended St. Philip’s as a body and officially commended Marston for his sermon.

Nobody in the province was aware of Marston’s prior reputation in England. He was said to have been a man of violent passions and a contentious disposition. He had been a member of the Jacobite movement during the reign of King William and had attacked the new government so vociferously that he was imprisoned for a short time. He was ordered to leave his cure in Nortonshire. After being reduced to poverty, he took the prescribed oath and embarked for Carolina. Marston later claimed that, having been deprived of a living, he had been “forced into exile.” 69

Although many did not approve of the Church Act of 1704 (discussed in the chapter entitled “The Early Years”), the most vocal opponent was the rector of St. Philip’s Church. Marston preached against Governor Johnson and his Anglican faction and kept notes ready should any of the High Church party appear in church.

During the controversy, the Assembly voted for the arrest and imprisonment of the Dissenters’ leader, Landgrave Thomas Smith, for “casting aspersions on their House.” When Marston visited Smith, the Assembly turned on him for his “Bold and Saucy attempt” to denigrate its body. It ordered Marston to produce the notes of two sermons. One had been preached on the Fifth Commandment to honor father and mother; Marston saw the church and its ministers as father and mother, those whom the civil authorities had failed to honor. The other sermon related to Acts 17 about Greeks who beat the ruler of the synagogue. Marston made it an indictment of the Assembly for failing to protect his person from mob action, as some Anglicans had verbally attacked Marston in the streets, and on one occasion, his clerical gown had been ripped off.

Marston refused to turn over the sermons, claiming that the Assembly had no power over ecclesiastical affairs and that he was responsible solely to the bishop of London and the governor. He complained in vain to Governor Johnson, who was already angry that Marston had visited Smith. The House heard about Marston’s appeal to the governor and appointed a committee to draw up charges for his reflections upon its body.

Marston was unrepentant and defiant when he appeared before the Assembly. The impasse finally came to a head when the Assembly withheld Marston’s salary and passed an act designed to remove him from the pulpit at St. Philip’s. The act created a board of lay commissioners that could, upon the request of nine parishioners and a majority of the vestry, remove a minister for immoral conduct, general unfitness or incurable unacceptability to the people.

By this time, Marston had become the hero of the Dissenters. Two Dissenting ministers examined his sermons and denied that Marston had compared the legislature to the rebel who had opposed Moses and that his assertion that his authority was derived by divine right through Christ was a direct quote from a book by a respectable Anglican bishop. The squabble continued. Marston complained bitterly to the SPG and the Lords Proprietor and continued to preach at St. Philip’s with no salary.

Meanwhile, the lay commission, composed of the governor and twenty men (fourteen of whom were in the Assembly), deposed Marston and declared his pulpit vacant. The authorities turned to the Reverend Atkin Williamson, even though Williamson had run afoul of the Assembly and been a prisoner for nearly a year because of a funeral sermon that allegedly reflected on a deputy.

In January 1705, eight armed men ejected Marston and his family from St. Philip’s parsonage to make room for another rector. Marston then went to Goose Creek, where he was poorly received by those whom he had so recently berated. He left and sailed to Virginia, fully intending to continue on to England. The fleet was detained because of an embargo, and Marston returned to Carolina in October.

When the second Church Act was passed in 1706, Marston agitated against it. In July 1707, the Assembly, then under the control of the moderates, gave Marston a £150 salary for his service at St. Philip’s from the time of his suspension to the decree of ouster by the commissioners. Governor Johnson and council refused to concur because of his ranting against them.

The deposed minister had to rent a house in Charles Town at exorbitant terms and claimed that he had to endure insults and inhumane treatment by Nicholas Trott and others. During his lack of employment as a minister, Marston pursued the occupations of physician, lawyer and poet.

Because of the shortage of ministers, in 1709 Governor Johnson asked Marston to travel through the southern parts of the province preaching, baptizing and holding services. When he returned seven months later, he found that the governor had been replaced, and he was not compensated as expected.

While he was gone, his wife petitioned the legislature for relief for herself and her four small children and was awarded the £150 previously promised in “full satisfaction of his pretensions.” She set up a small shop to maintain her family and was one of St. Philip’s most faithful communicants. Out of charity, Commissary Johnston and his wife took the family into their home.

Marston was elected rector of St. Andrew Parish, where he lasted only seven weeks. Commissary Johnston opposed Marston’s election on the grounds that Marston had disowned the bishop’s authority, calling him a “Rebel and Murderer,” and referred to the commissary as “sacrilegious, unjust, ignorant, lazy, covetous and schismatical.”

In 1711, the Assembly authorized the purchase of a slave for Mrs. Marston at a cost not to exceed sixty pounds and barred Marston from selling the slave. That same year, Marston unsuccessfully petitioned the Assembly to discharge his debts.

Marston went to New York, where he had been promised a parish with an allowance of fifteen pounds per annum, but he decided to return to England instead, leaving his wife and five young children behind. He sent a long petition to the Lords Proprietor reciting his vicissitudes and pleaded for help. Unfortunately, his contentious nature caused him to attack the deceased Reverend Samuel Thomas once again. Anxious to avoid further controversy, the Proprietors commanded the receiver general of South Carolina in 1715 to pay Marston £100, thus furnishing him the means to leave the province permanently. 70

In 1705, the Reverend Edward Marston was replaced at St. Philip’s by the Reverend Richard Marsden.

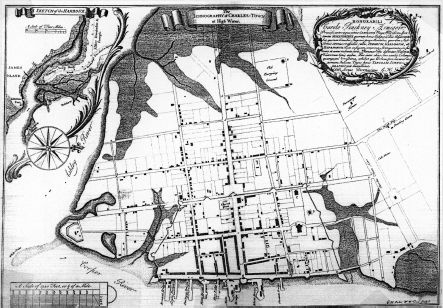

Ichanography of Charles-Town at High Water by B. Roberts, engraved by W.H. Toms, 1739. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

GIDEON JOHNSTON

From 1681 to 1781, the bishops of London licensed 114 priests to South Carolina. In the early colony, three of their representatives, called commissaries, were put over the Carolina churches. The first commissary was the Reverend Gideon Johnston, who arrived in 1707.

Johnston was born in Loony, County Mayo, Ireland, circa 1668, son of a “poor clergyman gentleman.” He entered Trinity College, Dublin, as a pensioner in 1684 and graduated with a BA degree in 1692. It was at Trinity College that he met Francis LeJau, with whom he later worked in Carolina. Johnston was a clergyman of the Diocese of Killala and Anchonry in Ireland when he married Henrietta de Beaulieu Dering in 1705. 71

Henrietta de Beaulieu’s parents were French Huguenots who immigrated to London in 1687. Henrietta had converted to Anglicanism while living in London. In 1694, Henrietta married Robert Dering, fifth son of Sir Edward Dering, Baronet. After her marriage, the couple joined a Dering brother in Dublin. She enjoyed life on a large estate, where she painted detailed and beautiful pastels of the extended Dering family, including the Earl of Barrymore and Sir John Percival, Earl of Egmont. (Henrietta Dering Johnston would later become famous as America’s first pastelist.)

The Derings had two daughters. Robert Dering died in January 1703, and his second daughter, Helena, died the following year; both were buried at St. Andrew’s Parish, Dublin. 72

At the time of her marriage to Gideon Johnston, Henrietta had one surviving daughter, who later became a lady in waiting for the daughters of George II. Johnston had two sons by a former marriage: James, age ten, and Robert, age eight.

Two years after their marriage, the couple made the decision to move to Carolina. Already in debt, they were hoping to receive funds from the settlement of an estate in Ireland. Bearing glowing recommendations from the archbishop of Dublin, Johnston took his family to London and applied for an appointment as a missionary for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) in 1707. The Society had just passed a regulation questioning the advisability of sending missionaries with families to the colonies; Johnston had applied before its final approval.

Because of Johnston’s large family group, the Society took its time approving the application. While cooling their heels in London, the Johnstons went deeper and deeper into debt. They ran out of funds before Johnston was finally appointed as rector of St. Philip’s Church in Charles Town and commissary of the Church of England in North Carolina, South Carolina and the Bahamas.

The journey to Carolina was full of misadventures. After leaving England, the vessel made a port call in the Madeira Islands. Johnston went ashore to buy fresh provisions and didn’t make it back before the ship left port. Still aboard the ship, Henrietta, her daughter and stepsons were forced to continue the journey to Carolina without him. 73

The commissary’s late arrival in Charles Town was nearly fatal. While their ship waited for the right tide, Johnston and two others impetuously attempted to get to Charles Town in a rowboat. His letter to the Society reads:

It happened that I was put ashoar, at a great distance from this Town upon a Sandy Island, with a Merchant and a Sailour, where we Continued 12 days and as many Nights, without any manner of Meat and Drink, or Shelter from the Scorching heat of the Sun. Miserable and almost incredible was the shift we made to subsist in that unhappy place for so long a time; and the Saylor being unable to bear the want of Shelter and Provision any longer did on the third day after our being Landed swim over to another Marshy Island in hopes to make his way to the Continent, but he Perished in the attempt. At last it pleased God to relieve us for upon the arrival of the Ship (in which we were) at this Town that upon our being missed, it was presently Suspected what became of us. Sloops and Boats, Perigoes and Canoos were dispatch’d to all such places as it was thought we might be in; and on the twelfth day in the Evening a Canoo got to us when we were at the last Gasp and just upon the point of Expiring, and Next Morning we were conveyed to the opposite Port of the Continent where I lay a fortnight before I could recover Strength enough to reach the Town . 74

The commissary arrived only to discover that the parsonage and his pulpit at St. Philip’s were occupied by the Reverend Richard Marsden, 75 a tall, imposing figure with a dark complexion marked with smallpox. He was charming and had become the darling of the people. The congregation liked Marsden and had elected him “in the Presbyterian manner.”

For several months, Marsden steadfastly refused to relinquish the pulpit and parsonage. The commissary went further into debt renting lodging for his family, and he had to borrow an advance on his salary from the Provincial Treasury, with Governor Nathaniel Johnson his surety. Trouble pursued him, for his accommodations were broken into twice.

Governor Johnson took the commissary’s side, and Johnston was finally installed as the legitimate rector of St. Philip’s on September 29, 1708. Only seven parishioners showed up on his first Sunday.

The parsonage was located outside the city walls. It was badly in need of repair but did possess a garden and untilled acreage. The minister was allowed two black slaves and a stock of cattle. Regrettably, the proximity to the marshes made it a haven for mosquitoes. Parsonage Lane (now part of Market Street) provided a convenient shortcut to the church, located just beyond the drawbridge into town. 76

Unhappy with his decision to come to Carolina, just before his installation, the commissary wrote to his superiors: