Part II

SECOND ST . PHILIP ’S CHURCH

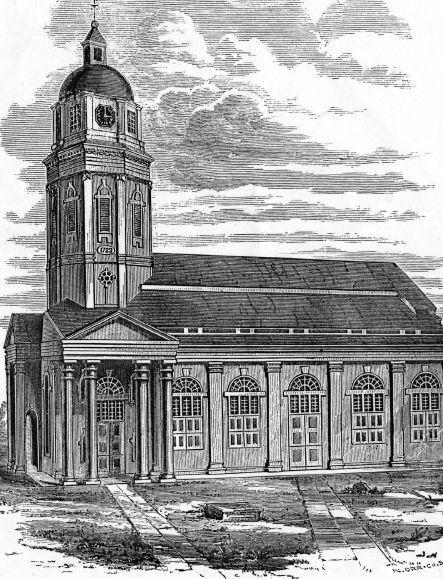

Second St. Philip’s Church; drawing by William Birch, circa 1810. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

THE NEW ST . PHILIP ’S CHURCH

In December 1720, the Assembly passed an act to rebuild the brick church that had been started while Gideon Johnston was commissary. The act described the deplorable condition of the 1680–81 wooden church, stating that it would “inevitably in a very little time fall to the ground, the timbers being rotten, and whole fabric being entirely decayed, so that the whole town will be left without a fit and convenient place for public divine worship.” 91

Five Anglican lay commissioners were appointed to manage the project: Major Thomas Hepworth; Ralph Izard, Esq.; Major William Blakeway; Mr. William Gibbon; and Colonel Alexander Parris, who had served on the previous commission as treasurer. They were tasked with completing the church, enclosing the churchyard and receiving subscriptions and donations. A tax on rum, brandy and other spirits was instituted to fund completion. 92

The final design of the church was remarkably similar to what was au courant in London. The person who designed the church is unknown, but two South Carolina governors are possible candidates: Governor Edward Tynte, who introduced Palladian architecture to Charles Town, and Sir Francis Nicholson, governor from 1721 to 1725. Nicholson had been governor of both Maryland and Virginia when the city plans were developed for Annapolis and Williamsburg, respectively. Nicholson arrived in Charles Town in 1720. His motto, Deus mihi sol (“God is my sun”), appeared over the central arch of the north nave of the church, and his personal pew was prominently located in the sanctuary.

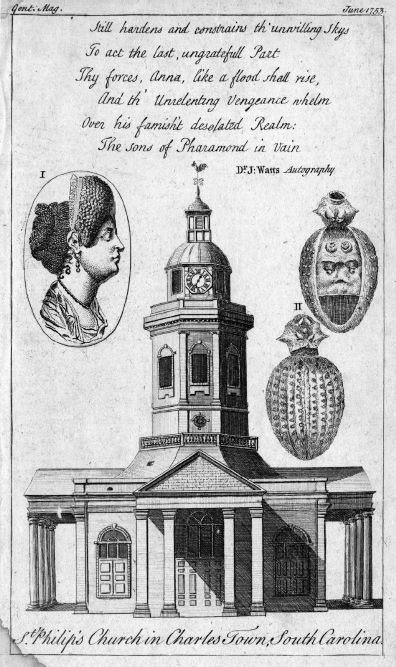

Gentlemen’s Magazine (June 1753). Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

St. Philip’s church was unique among churches in British America, and its sophistication influenced the design of other buildings in the province. It is the only known colonial building to be pictured in a contemporary European magazine. And in England, British statesman Edmund Burke described St. Philip’s as “spacious and executed in a very handsome taste, exceeding everything of that kind which we have in America.” 93

In 1826, the celebrated Charleston architect Robert Mills made drawings of the church and wrote:

THE GENERAL OUTLINE OF THE PLAN presents the form of a cross, the foot of which, constituting the nave, is seventy-four feet long and sixty-two feet wide. The arms from the vestibule, tower, and porticoes at each end, projecting twelve feet beyond the sides, and surmounted by a pediment. The head of the cross is a portico of four massive square pillars (intercolumniated with arches), surmounted with their regular entablature and Crowned with a pediment. Over this portico, and behind it, rise two sections of an octagon tower, the lower containing the bell, and the upper the clock), crowned with a dome, and a quadrangular lanthorn and vane. The height of this tower entire, with its basement, is 113 feet .

The sides of this edifice are ornamented with a series of pilasters of the same order with the portico columns (which are Tuscan), each of the spaces pierced with a single lofty aperture with a window. The roof is partially hid by a balustrade which runs round it .

The interior of this church in its whole length, presents an elevation of a lofty double arcade supporting upon an entablature a vaulted ceiling in the middle. The piers are ornamented with fluted Corinthian pilasters rising to the top of the arches, the key stones of these arches are sculptured with cherubim in relief…. At the end of the nave is the chancel (within the body however of the church), and at the west end is the organ… .

The galleries were added some time subsequent to the building of the church. It is to be regretted that the steeple of this venerable edifice was not furnished with its spire, as was evidently at first intended; and that the interior grandeur of its massy arches has been disturbed by the introduction of galleries, which never constituted a part of the original design . 94

The interior was embellished with Corinthian and Ionic pilasters, as well as Tuscan columns and sashed windows with Venetian blinds. The organ was imported from England and had been used at the coronation of George II. There were rich pulpit cloths and coverings for the altar. “The Communion Plate was a donation to the Church. Two Tankards, one Chalice and Patine, and one large Alms Plate, were given by the government, and have the Royal Arms of England engraved on each piece. One Tankard, one Chalice and Patine, and one large Alms Plate, have engraved on them, The Gift of Col. Wm. Rhett to the Church of St. Philip. Charles-Town, South-Carolina . One large Paten with I.F.R. engraved. The Pulpit and Reading Desk stand at the East end of the Church, at the N.E. corner of the middle aisle.” 95

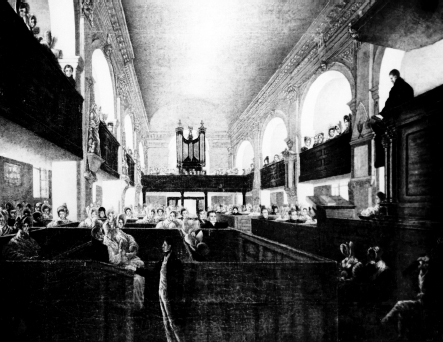

Second St. Philip’s Church; interior, looking west, by Thomas Middleton. (Eighty-eight box pews filled the floor of the church, with those near the pulpit reserved for the governor, king’s officers and masters of merchant ships; the galleries have sixty pews.) Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

The exact date the church was opened for worship is unknown. Bishop Gadsden mentioned in the consecration of the replacement church that it was opened for worship on Easter Day 1723. (According to Dalcho, the church was not completed until 1733.) There is a tradition that for some time after the church was opened, members of the congregation brought their own chairs to church.

In 1739, an attempt was made to obtain a “ring of six bells” and a clock by raising £1,192 currency by subscription; however, the sum was insufficient. Five years later, the vestry ordered a plain, substantial church clock, “completely fitted for the steeple, to go for eight days, and also a good bell of about 600 weight.” 96

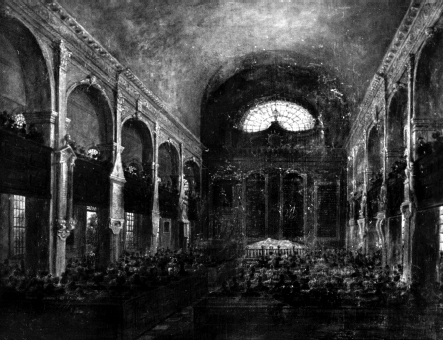

Second St. Philip’s Church; interior, looking east, by John Blake White, 1835. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

The church clock and bell arrived after a fifteen-year wait and were promptly returned as unsatisfactory. Robert Pringle, the church warden, described their disappointment: “[As] to the Bell, it appears to be a Very bad one, whether from the Badness of the Metal or from the cast we do not know; but so it is, that it Sounds as from under a Dunghilll & so low, that it can Scarce be heard at the Distance of two or three hundred yards.” 97

Second St. Philip’s Church; south side. From Bishop Howe’s Sermon (1875). Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

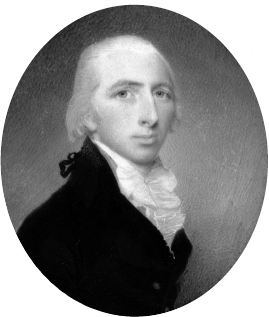

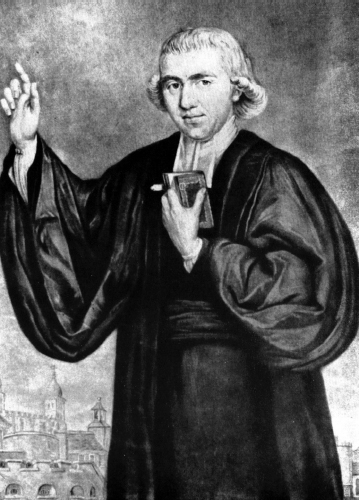

ALEXANDER GARDEN

Alexander Garden was born in Scotland. After graduating from the University of Aberdeen, he served as curate of the prestigious All Hallow’s Church by the Tower of London. 98 He was sent as rector to St. Philip’s in 1719 and was made the third commissary in 1729, following Treadwell Bull. He held that position until his retirement in 1755.

Garden was thirty-four years old when he arrived in the colony. This coincided with the peaceful overthrow of the government of the Lords Proprietor. Governor Robert Johnson, a popular official, had refused to take part in the coup. He was subsequently deposed but continued to serve as president of the Church Commission, the body with the authority to approve new missionaries and ministers sent from England.

Johnson called a meeting of the clergy to approve Garden, but they refused to come. Animosity toward the Propriety government was still high, and Garden waited for weeks along with the Reverend Peter Tustian, who had also been awaiting approval. Tustian was eventually sent to St. George, Dorchester. Garden, likewise, was approved and assumed his duties as rector of St. Philip’s in 1719. 99

Garden faced many challenges. One of them was getting a new house of worship for the town’s growing Anglican population. The old wooden church building near the city gates was in a deplorable state, and the ruins of the new brick church, victim of the 1714 hurricane, sat unfinished three blocks away.

After the interim royal governor Sir Francis Nicholson arrived in 1721, the Assembly authorized construction of a new church building on the site of the ruins at the head of Church Street. 100 The new commissioners acted quickly, and the first services in the new St. Philip’s were held on Easter Sunday 1723.

When Commissary Treadwell Bull took a long-delayed leave of absence to see his widowed father in England in 1723, he never returned to the colony. 101 Garden was appointed to succeed him in 1729. Following his appointment, the new commissary began convocations of the clergy in 1730, and this greatly improved communication with the country churches. The majority of the clergy were dedicated, well-educated, deeply committed men. They received low salaries in a time of inflation. They nourished an infant Anglican Church and spread the gospel among ignorant settlers.

However, there were a few miscreants and scoundrels among the clergy. Judging from his letters to the SPG, Garden spent much time and energy dealing with them. There were charges of unashamed drunkenness and whoremongering against the Reverend Brian Hunt, a graduate of Cambridge and a naval chaplain. He was sent to St. John’s Berkeley. Deeply in debt, Hunt had been willing, for a fee, to marry couples not approved by other clergy. He went so far as to join one couple at midnight over her guardians’ objections. The teenage bride happened to be an heiress, and Hunt was forced to resign. He went to Barbados and died there two years later. 102 The Reverend John Whiteley, then serving at Christ Church in Mount Pleasant, was an admitted drunkard and whoremonger. He was sent as chaplain to the Savannah Garrison on the Georgia frontier. He asked the Assembly for passage back to England but died of a fever before that body could grant his petition. 103

Garden’s first decade in the colony was marked with periods of unrest and destruction. The Crown levied higher taxes, causing small farmers to go bankrupt; they physically prevented creditors from collecting money owed them. By June 1727, the farmers had become so frustrated that they marched on Charles Town in armed rebellion. Governor Arthur Middleton called the militia to control the mob, only to see it join the protesters. 104

The summer of 1728 witnessed a prolonged drought. Ponds dried up, crops drooped, livestock died and yellow fever struck the city once again. Food supplies dwindled as farmers from the backcountry ceased coming to town for fear of contracting the fever, and food prices soared. People went hungry, and many residents succumbed to the fever. Suddenly, in the middle of August, a violent hurricane struck. The drought was over, but the city was wrecked. Ships in the harbor were smashed, as were wharfs, houses and fortifications. 105

In spite of conflicts, epidemics and natural disasters, the decade of the 1730s was also one of growth and prosperity. Crops were bountiful and trade in naval stores, deerskins, beef, pork and Carolina rice flourished with only occasional interruptions. A newspaper, the South Carolina Gazette , began publication; a theater and a book store opened; dances were held; and concerts were presented. The highlight of the social season was Race Week, an event that shut down the town for festivities that involved the entire community, including schoolchildren. 106

It took years to work out the transfer of ownership of the colony to the Crown. The last Proprietary governor, Robert Johnson, had returned to England after refusing the governorship in 1719 during the “bloodless revolution.” He spent the next ten years seeking a commission for a royal governorship. When the Proprietors decided to sell the colony, because of his integrity he was chosen to negotiate the transaction. In 1729, the Privy Council approved his appointment as royal governor, and he returned to the province in 1732. To ensure that his loyalties in the colony were not compromised by his interests in England, Johnson divested himself of his patrimony before he returned to the province.

A yellow fever epidemic struck the city in July 1732 and brought all business to a halt. The toll of bells was prohibited because of the numerous daily funerals. Commissary Garden was kept so busy burying the dead, visiting the sick and consoling the bereaved that he contracted the fever himself. He wrote to the bishop of London telling him of the violent fever that raged from July through the middle of August. Every home looked “like a hospital and the whole town was one single house of mourning.” There were five to ten burials a day. 107

Although many of the well-to-do fled to their homes in the country, Governor Johnson believed that he was duty-bound to remain with his citizens in the city. The epidemic ended in September when the cool weather killed off the mosquitos. Governor Johnson lost his wife, a son and three servants, who were among the 130 citizens and numerous slaves who died. 108

In his letter of April 1733, Garden praised General Oglethorpe, who arrived in January on his way to establish the town of Savannah, which was intended to provide a bulwark between the Spanish in St. Augustine and the Carolina colony. 109

Garden’s problems continued. On May 4, 1734, Clerk John Fulton, also called “Fuller,” appeared before the first Ecclesiastical Court at St. Philip’s, with Commissary Garden as his judge. His sentence was to be denounced in front of the church and fined ten pounds for drunkenness; if payment was not forthcoming within a month, he would be excommunicated. Garden sent the bishop of London a copy of the formal proceedings, written in Latin, asking if his proceedings were within English canon law. Mr. Fulton turned to rice planting, “his morals rather worse than before.” 110

In 1735, after a long illness, Governor Johnson died. His high-minded character and administrative capabilities had endeared him to people, who called him the “good governor.” Johnson’s greatest success had been the restoration of social and political harmony in the colony. The governor had been able to help reduce the debt and maintain a balance in the government that had been lacking during the administration of his predecessor, Arthur Middleton. Before Johnson’s arrival, the clash between local factions had practically shut down the government. The Assembly had stopped meeting, taxes had gone uncollected and the courts were at a standstill. The colony had seemed on the brink of anarchy. 111

The colony’s first state funeral was held in Governor Johnson’s honor. The South Carolina Gazette described the funeral’s pomp and circumstance in its obituary of May 10, 1735. Two companies of militia led the procession and served as an honor guard, royal councilors were pallbearers and members of the Lower House of Assembly were official mourners. The Gazette noted:

He had on his advancement [to governor] disposed of all his patrimony in England so that his interest might concur with his inclination in promoting the welfare of that country his Majesty had done him the honor to entrust him with the care of, and accordingly always kept up a good correspondence with the Assembly, as they were all fully convinced by the whole tenor of his conduct that the interest of the province lay principally at his heart. But it is needless to enlarge upon a life and character so well known and which has rend’d his death so universally and deservedly lamented of the whole Province . 112

After the funeral service, the governor’s remains were interred near the altar of St. Philip’s Church. Later in the year, the General Assembly erected a wall monument to his memory. (The monument was consumed in the fire of 1835.)

That same year, Garden’s health had deteriorated so severely that his physicians advised his immediate departure from the province. It was too late in the year to sail for England, so in July, he left for New York to take advantage of the cooler climate of New England. Having an opportunity to rest and enjoy horseback riding in the fresh air improved his health so much that the commissary rode his horse from Rhode Island to Boston and finally back to Charles Town, a journey of 1,200 miles. Sadly, Garden’s improved health was only temporary. 113

In his absence, the Assembly had taken the precaution of asking the bishop of London for an assistant; the Reverend William Orr arrived in April 1737. 114 That same year, Mrs. Garden died, and the commissary was left with four young children, ages six months to eleven years. Garden was fifty-one years old.

In May 1738, a slave ship from Guinea missed a smallpox diagnosis at the quarantine station and sailed into town, bringing the deadly scourge with it. A violent epidemic erupted in which “there were not a sufficient number of persons to attend the sick, and many persons perished from neglect and want…there was scarcely a house in which there had not been one or more deaths.” 115 The governor declared a day of “Public Fasting and Humiliation” to be conducted at St. Philip’s. 116

St. Philip’s churchwardens rented a house to take care of the indigent patients. During the epidemic, inoculation was tried for the first time. Dr. James Kilpatrick, the church physician, had been attempting to concoct a vaccine for the pox and offered experimental inoculations. Although extremely controversial, between eight hundred and one thousand people volunteered, including the wife of Robert Pringle and her brother, William Allen. There were only six white and two black fatalities among the inoculated. 117

In 1739, word reached the province that war had broken out between England and Spain, and the colonists began building up Charles Town’s fortifications. The citizens remained in a constant state of vigilance both day and night. The tensions heightened in September when a number of slaves, at the instigation of the Spanish in St. Augustine, broke into a Stono store and murdered the young men in charge. They took guns and ammunition and began marching toward Florida with drums beating and flags flying. The mob proceeded to the home of a Mr. Godfrey and stole more arms before burning his house. They continued on, killing, burning and plundering as they went. The slaves were finally intercepted as they were setting fire to a plantation in Colleton County later called “Battlefield plantation.” The leaders were captured, tried and executed. Those who had been compelled to join were pardoned. The “Stono Rebellion,” as it was called, created shock waves in the colony. As other plots were discovered, the settlers became more and more uneasy about the possibility of another slave insurrection. 118

The Trial of George Whitefield

The Reverend George Whitefield was a dynamic Anglican minister who was part of the religious movement called the Great Awakening. His first visit to Charles Town was made to raise money for an orphan house in Georgia. He arrived in August 1738 en route to Savannah. Hoping for contributions in Charles Town, he spoke at the Congregational Church on Meeting Street, then under the Reverend Josiah Smith, grandson of Landgrave Thomas Smith. Whitefield also paid a call to Commissary Garden. Considering him to be one of the Anglican flock, Garden invited Whitefield to preach at St. Philip’s Church, morning and evening.

Whitefield later returned to England, where he was enthusiastically received, sometimes preaching to crowds of more than twenty thousand persons. It is said that his voice could be heard a mile away. His high-powered sermons reduced his audiences to weeping, fainting and outbursts of emotion. This alarmed the bishop of London, and he published an admonition to his clergy, including those in the colonies, to avoid extremes of “enthusiasm.” 119

Whitefield was back in America in 1739. He preached the gospel throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina before he stopped again in Charles Town. He was eagerly welcomed by the Congregational Church. The crowds were so large that he sometimes was forced to move into the churchyard. Worse, in Garden’s opinion, he sometimes supplemented the Book of Common Prayer with extemporaneous prayers.

Commissary Garden was prepared to defend the Anglican Church, its theology and the Book of Common Prayer . He tried to reason with Whitefield but made no impression whatsoever. The charismatic Whitefield continued to preach in Charles Town. Letters flowed back and forth between the commissary and the evangelist in the South Carolina Gazette , and the community joined in the animated debate. Finally, in July 1740, the commissary resorted to an ecclesiastical court. Whitefield appeared with his lawyer, Andrew Rutledge, and contended that the court had no jurisdiction over him. The plea was overruled. Whitfield subsequently left the colony and appealed to the Lord’s Commissioners in England, who were appointed by the king for hearing appeals in spiritual cases in America. The appeal was allowed, but Whitefield did not prosecute it. The case proceeded through the courts. Many months later, Garden’s court suspended Whitefield in absentia. 120

Whitefield left a deep impression on the religious lives of the people of America and England. He visited America seven times, making thirteen transatlantic crossings in total. He stirred a generation to examine their faith and take a stand for their beliefs. In Charles Town, Whitefield left a breach between the Dissenters and Anglicans that took years to heal.

McCrady’s commentary bears repetition: “Unfortunate indeed was it for the Church of England that it could at that time find no means of availing itself of the great work of the Wesleys and of Whitefield; unhappy indeed that it allowed a great and needed revival to end in a schism instead of reformation.” 121

Commissary Garden’s Last Years

The “Great Fire” of November 18, 1740, was by far the most devastating that occurred in the city since it had been founded. It began in a saddler’s shop on Broad Street between Church Street and East Bay. The ravenous flames rapidly consumed every house south of Broad Street and some on the north side. Wharves, storehouses and produce were all destroyed. Everyone was affected. 122

Garden informed his bishop, “A sore calamity has lately befallen poor Charlestown, viz. a very dreadful fire, which burnt a full third part of it to the ground. Damage computed £100,000 Sterling at least; £500 of which has fallen the Share of myself and children.” He continued that the disaster was “still the heavier” because of the defeat at St. Augustine, which was attributed to the “ill conduct” of the commanding officers. 123

St. Philip’s vestry began distributing relief two days after the fire. A solemn fast was held ten days later. Collections and subscriptions were taken at churches. The Assembly appropriated £1,500 to be paid to St. Philip’s churchwardens for the relief efforts. Goods were donated locally, as well as from the other colonies, and the royal government sent £20,000. (This was the only time Parliament sent the colony relief funds.) The vestry continued to meet daily for six months to distribute goods and supplies. 124

Garden’s nephew, the Reverend Alexander Garden Jr., arrived from England in 1743 and became rector of St. Thomas and St. Denis. His arrival brought the number of “Alexander Gardens” in the community to three. The third Alexander Garden was the famous botanist for whom the gardenia was named. All made their imprint on the history of Charleston, and some of their descendants still sit among the members in St. Philip’s. The botanist Garden was a Tory and returned to England at the time of the Revolution. 125

After his encounter with Whitefield, Garden organized a school to educate the slaves. Because of the Stono Rebellion, there was tremendous opposition from the planters, who feared that slaves who could read would be more inclined to revolt. Garden held that it would make them happier people and more cooperative with their masters if they learned true Christianity. His opinion prevailed. A schoolhouse financed by private donations opened in September 1745.

Garden thought that the black residents would receive instruction more readily from one of their own. The SPG underwrote the purchase of two intelligent young black men who were baptized Henry and Andrew. Garden hoped that if the experiment succeeded in the city, it would be used in the country parishes. He envisioned an annual graduation of thirty to forty pupils. Bibles, prayer books and spelling books were provided by the SPG. Under Garden’s supervision, the school flourished. Within four years, the number of pupils had increased to fifty-five children and fifteen adults. The death of Andrew and the loss of Henry (who “turned out profligate”) brought the school to an end in 1757. 126

In September 1752, a furious hurricane smashed into the city, arriving without warning. The summer had been unusually hot when the storm hit. Wind-driven water filled the harbor in a few minutes, causing the tide to rise ten feet above the spring high-water mark. The creeks intersecting the town rose, and water coursed down Broad Street to the artificial pond, where the drawbridge had been (near present-day St. Michael’s Church). City residents found themselves up to their necks in water amid bobbing canoes, wrecks of boats, masts and barrels. Many escaped by boat; others sought refuge on Sullivan’s Island. Half a dozen floated up the Cooper River on the roof of a house. Before long, vessels were driven ashore, except the sloop of war Hornet , which rode out the storm by cutting away the masts. Suddenly, the wind dropped only to return with equal violence from the opposite direction, as is common with hurricanes after the eye passes through.

The damage was enormous: wharfs and bridges were ruined, and every building was beaten down. A pilot boat was dashed against the governor’s residence on Bay Street (the Pinckney House), knocking a hole in the second-story front wall. Most of the tiled or slated roofs were uncovered, and great quantities of merchandise in the stores on Bay Street were damaged. Fifteen people in the city died, plus more on James Island and in Mount Pleasant.

Vestry minutes report that St. Philip’s was busy almost immediately, giving aid to the devastated community. Restoration of the town began by filling up creeks and low places. The artificial pond was filled in, and some years later, the South Carolina Statehouse was built on the site. The town’s streets were extended from river to river. The sea wall extending from Granville Bastion along Vander Horst’s creek was damaged, and a surveyor from Savannah ran a new line for the sea wall that is still in use today. It is now known as “The Battery.” 127

When Garden’s health deteriorated, he appealed for a replacement in 1748, but his pleas went unanswered. He stayed at his post until St. Michael’s was started in 1752. By 1753, the commissary was suffering from palsy, and age was having a visible effect on him. He notified the vestry of his intent to resign. His assistant, the Reverend Alexander Keith, also in bad health, gave notice at the same time and left for England, leaving Garden with the responsibility of ministering to two thousand souls. The vestry immediately contacted the bishop of London, and Garden made his leaving contingent upon the arrival of ministers for both parish churches.

When the Reverend Richard Clarke and the Reverend John Andrews arrived, Garden formally resigned and bid farewell to a packed church on March 31, 1754. The congregation bid a regretful adieu to the much-loved rector. The vestry voted more than fifty-two pounds sterling for a silver plate that was engraved with a view of the west front of St. Philip’s. A glowing testimonial, signed by a large contingent of the congregation, accompanied the silver plate. Garden departed for England with his family, fully expecting to remain there for the rest of his life. 128 However, this was not meant to be.

The commissary’s son, John, had gone to London to study law some time before 1748. Initially, he did quite well, according to Henry Laurens, who wrote to the commissary from London in December 1748. But things changed. John Garden began to perform poorly and left his teacher, who refused to take his pupil back. John was later arrested for a tailor’s bill of more than £100 and ended up in debtors’ prison. His father arrived in England too late to get him out of prison, for the errant son had forged his father’s name to a letter, gotten £20 from his father’s account and fled from Exeter prison. 129 This broke his father’s heart.

Eliza Lucas Pinckney wrote from London, “The good old Gentleman [Alexander Garden] is really to be pitied! He takes his Son’s Ill-Conduct so much to Heart, that he will not come to London; because he says his Son’s Misconduct affects him so much that he cannot see his Friends with pleasure.” 130

It was not long before Alexander Garden and his family returned to Charles Town. The English climate had not improved his health, and he missed his friends in America. Young John also returned home. According to St. Philip’s register, John Garden, aged twenty-two, was buried in St. Philip’s Churchyard on July 15, 1755. His father died on September 29, 1756, and was also buried in the churchyard. (There is no explanation of what caused John Garden to die so young.)

In gratitude for Garden’s years of faithful service, the vestry financed construction of a handsome tomb. It is located in the east churchyard and surrounded by a cast-iron fence. 131 A large slab, now difficult to read, lists the names of Commissary Garden’s wife and their children, John Garden among them.

St. Michael’s as it looked when the statue of William Pitt the Elder was erected at the intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets in 1770. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

ESTABLISHING ST . MICHAEL PARISH

The Act of June 14, 1751

By 1751, Charles Town had become the third-largest town in British North America, surpassed only by Boston and Philadelphia. The population had increased to twenty-five thousand whites and thirty-nine thousand blacks, and the city had grown so much that the government was prepared to build a new set of public buildings. Among them was a new Anglican church that would ease the crowded pews of St. Philip’s.

On the same day that St. Michael’s was approved, Governor James Glen signed legislation for building a new statehouse and a new guardhouse, to be placed at the same intersection that had been reserved for public buildings when the town had been laid out. The waterfront site of the old guardhouse at the foot of Board Street later became the site of the handsome Exchange and Custom House. 132

The act authorizing the new Anglican parish (St. Michael) stipulated that St. Philip’s congregation be split by residency, with the half living above Broad assigned to St. Philip’s and those living below Broad assigned to St. Michael’s. The act directed that the new church be erected on or near the place where the old wooden St. Philip’s stood, at a cost to the public not to exceed £17,000. A new rector was to be paid £150 per year and enjoy the same privileges as the other ministers in the province.

A special pew was set apart for the governor and council, and two large pews were set aside for members of the Assembly, along with another pew set aside for strangers. The remaining pews were to be of equal size, with those who had contributed the most toward the building of the church having first choice.

St. Philip’s churchwardens and vestry were authorized to continue to assess and collect the taxes for the support of the poor, including those in the new St. Michael Parish. Representation in the Assembly was equally divided between the two parishes. To prevent families from being separated, the inhabitants of either parish could bury their dead in either parish. No one was permitted to have pews in each church unless he owned a house each parish. 133

Nine commissioners were appointed to oversee the building of the church and parsonage and to receive subscriptions. The commissioners named were “the Hon. Charles Pinckney, Messrs. Alexander VanderDussen, Edward Fenwick, William Bull, jun., Andrew Rutledge, Isaac Mazyck, Benjamin Smith, Jordan Roche and James Irving.” Before the new church was completed, other commissioners were appointed to fill vacancies caused by death or resignation: Othniel Beale, George Saxby, Gabriel Manigault, Robert Pringle, Thomas Middleton and James Graeme. 134

Although Commissioner Charles Pinckney was an amateur architect and Gabriel Manigault, the grandfather of the noted amateur architect of the same name, architectural historian Gene Waddell suggested that Robert Gibson and Samuel Cardy were probably responsible for the design of St. Michael’s. Gibson, a Scotch engineer, published The Theory and Practice of Surveying (circa 1765), a standard work that remained in print until 1840. Cardy, a master builder and carpenter, has been credited as the principal architect, including for the interior appearance and the omission of planned porticoes on the sides of the church. It should be noted that Gibson was only nineteen in 1751 and still at Oxford; he did not reach Charles Town before 1753. 135

Building St. Michael’s Church

The commissioners lost no time in getting started on the new church. Preparatory work on the site was underway by September, and a plan for the design was advertised the following month.

On February 17, 1752, Governor Glen laid the cornerstone in an auspicious ceremony that was followed by a grand dinner. Afterward, attendees drank to His Majesty’s health, followed by a salvo by the Granville Bastion cannons. Then the health of the royal family and other royal toasts were announced and drunk. According to the Gazette , the day was concluded with peculiar pleasure and satisfaction. 136

During the first five months of construction, master bricklayer Humphrey Sommers laid almost all of the 214,100 bricks purchased. This was enough for the foundations and for the walls to be raised to the point where scaffolding was needed. In May, master builder and carpenter Samuel Cardy was hired. Brickwork on the church progressed rapidly, and by October 1753, more than 1 million bricks had been laid. By January 1754, the public treasurer had paid out £15,000, and it was obvious that the church would cost far more than originally anticipated.

The commissioners had expected the sale of pews to raise the remaining funds. In spite of their diligence, the costs continued to escalate with no end in sight. The possibility of Britain declaring war on France caused justifiable concern about depleting the treasury. As a result, no new appropriations were made for St. Michael’s until 1757. When the commissioners pointed out that the steeple could be used as a landmark to guide ships into the harbor, money was finally allocated to the church.

The architecture of St. Michael’s was patterned after St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London. The main body of the church is brick covered with stucco; the steeple and portico were made of wood. The freestanding Doric portico was similar to that at St. Philip’s. Evidence indicates that St. Michael’s original design included porticoes for the sides of the church; however, as costs mounted, these side porticoes were eliminated. The identity of the architect(s) is still subject to debate. 137

The final cost of the building was £53,535 8s 9d , of which £31,656 15s 9d was granted by the Assembly and £21,877 was raised by selling pews. 138

The first service at St. Michael’s was performed in February 1761. From the very beginning, the congregations of St. Michael’s and St. Philip’s enjoyed a harmonious relationship and functioned very effectively together.

Saga of the Bells

St. Michael’s famous bells were purchased by public subscription. The ring of eight bells with a tenor (the largest bell) of 17.5 centum weight (1,945 pounds) was cast in 1764 by Lester and Pack of London. They reached Charles Town that same year.

During the Revolution, when the city was evacuated by the British 1782, one of the British officers took the bells to London as a prize of war. A merchant who had formerly lived in Charles Town recognized the bells, bought them and shipped them back. When the bells arrived, the citizens were overjoyed. They hauled them with their own hands to the church and replaced them in the steeple.

From then on, the bells rang out every evening at curfew and on all occasions of rejoicing and mourning; they called the congregation to worship every Sunday until 1862. When the Union army besieged Charleston, the bells were once again removed and sent to Columbia for safekeeping. Sherman’s army burned Columbia in 1865, and the bells were cracked when the shed in which they were stored burned.

At the war’s end, the vestry reclaimed the bells and sent them to the successor of the house that had originally cast them. The bells were recast with the same amalgam in molds made with the same trammels. The bells were returned to Charleston once again, and according to McCrady, “no difference whatsoever could be distinguished in their tones from of old.” The curfew was rung on the bells, except during the war, until September 4, 1882, a period of 162 years. 139

RICHARD CLARKE

The Society for the Preservation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) sent the Reverend Richard Clarke to replace Commissary Garden. Clarke was born into the local gentry in Winchester, England. He attended University College, Oxford, and was ordained a deacon in the Church of England in 1746 and a priest in 1750. He was a curate and lecturer at Nicholas Cole Abbey in London when the SPG selected him.

Clarke arrived in Charles Town accompanied by the Reverend John Andrews. They were duly chosen as rector and assistant minister of St. Philip’s Church, respectively, on October 29, 1755. Andrews did not stay long. He resigned in November 1756 and returned to England. He was succeeded by the Reverend Robert Smith. 140

The new minister entered upon his duties at St. Philip’s with a deep sense of responsibility and a determination to walk in the footsteps of his esteemed predecessor. Although his style differed from Garden’s, he won ready acceptance from the congregation. The following testimonial was given Clarke by the vestry:

The Rev. Mr. Clarke was more known as a theologian beyond the limits of America than any other inhabitant of Carolina. He was admired as a preacher both in Charles Town and in London. His eloquence captivated persons of taste—his serious preaching and personal piety procured for him the love and esteem of all good men. When he preached, the church was crowded, and the effects of it were visible in the reformed lives of the many of his hearers, and the increased numbers of serious communicants. His sermons were often composed under the impressions of music, of which he was passionately fond. From its soothing effects, and from the overflowing benevolence of his heart, God’s love to man, peace and good will among men, were the subjects on which he dealt with peculiar delight. He gave on the weekday a regular course on the Epistles to the Hebrews which were much admired . 141

Clarke’s Christianity went beyond denominational boundaries. He made warm friendships with local ministers and members of other denominations, and they formed a religious and literary society that met in the homes of the members. It was an ecumenical group: William Hutson, the minster of the Congregational Church; Philip Morrison, the minister of the Wappetaw Independent Presbyterian Church at Wando Neck across the Cooper River; Gabriel Manigault, Benjamin Smith and Henry and James Laurens, leading members of St. Philip’s congregation; Daniel Crawford and John Rattray, prominent Presbyterians; and others. Another example of his ecumenical cooperation was endorsement of a book by John J. Zubly, a Presbyterian minister whom George Whitefield had called his “son in the Lord.” Clarke’s preface declared that “[t]he reader would not find a single word to corrupt the Heart.” 142 Clarke also became deeply interested in the “Negro School” started by Commissary Garden. Under his supervision, the school continued to flourish. 143

Things went well until four British transports carrying exiled French Roman Catholics from Acadia arrived on the morning of November 17, 1755. They were a part of the French Canadian exiles who had refused to take an oath of unconditional allegiance to Britain after Louisburg had fallen during the French and Indian War. The Acadians had witnessed their homes torched, their crops destroyed and their cattle slaughtered before they were loaded onto transport vessels destined for British colonies along the Atlantic seaboard.

The deportees were a resentful and miserable people when they arrived at Charles Town. Governor James Glen managed to make arrangements to feed and house the exiles and place them under military guard. The health of the Acadians soon began to deteriorate, and many died. The South Carolina Gazette noted on May 7, 1756, that “upwards of 80 Acadians went from hence in Canows [canoes], for the Northward: The Country Scout-Boats accompany them as far as Winyah. Yesterday upwards of 50 more of those People went for Virginia, in the Sloop Jacob Capt. Noel.” The Gazette also reported that five or six Acadians had robbed John Williamson’s plantation and terrified his wife.

As more shiploads of unfortunates arrived, complaints grew. A decision was finally reached to parcel the Acadians among the parishes, with St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s to assume the care of one-fifth. The exiles were dispersed among the parishes in August 1756. St. Philip’s vestry minutes were explicit: “His Excellency the Governor by Order under his Hand directed to the Church Wardens and Vestry requiring them to receive from the Commissary General 32 men, 33 women, 40 boys, and 32 girls, Acadians, to depose of them agreeable to the Act of General Assembly of this Province.” 144 St. Philip’s vestry, usually responsible for outreach in the city, adamantly refused to assist, although individuals in the community helped privately as much as they could.

The king finally sent orders that the Acadians be detained until he could send other instructions. The Acadians were virtual prisoners, and citizens who objected to their presence were required to house them and feed them. At least three groups of South Carolina Acadians tried to “escape” to the west over land. When the officials suspected that the Acadians might join forces (militarily) with the Indians, they chased after them. Two of the groups were retrieved, while another made its way to the Santee River Valley, stealing weapons and supplies on the way. Only two of the group are known to have made it to Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Valley. The Acadian problem continued for five years.

In 1756, the newly arrived Governor William Henry Lyttelton decided to make a name for himself. He was considered a pompous braggart of mediocre capabilities. Ignoring the advice of Lieutenant Governor William Bull, he raised an army and rushed to the upcountry to settle the Indian question. The campaign was a disgraceful disaster. Lyttelton captured a friendly Indian delegation under a flag of truce, and the Indians retaliated by massacring white settlers. Many of Lyttelton’s men contracted smallpox from Indian villagers and brought the dreaded disease back to Charles Town, causing another devastating epidemic. At the time, there were 340 Acadians in the town. A committee of the Commons House recommended they be quarantined as hastily as possible to prevent further spread of the disease into the community. The epidemic was severe, and almost every family lost some of its members. 145

In spite of this disaster, the new minister at St. Philip’s Church was a popular preacher. Nonetheless, trouble loomed on the horizon, and the seed was sown that led to Clarke’s departure from religious orthodoxy.

According to an unpublished manuscript by Citadel professor Lyon Tyler, a sailor died in the Charles Town workhouse. The authorities found a worn document stuffed into his seaman’s chest. The contents seemed to be of a religious nature, and the chief justice delivered the document to Mr. Clarke.

It was a tract containing a prophesy by Christopher Love, a Presbyterian minister. He had been found guilty of conspiring against the Puritan regime for writing letters to exiled Charles Stuart (later King Charles II) and his mother, the former queen of Charles I. While in prison, he had predicted the end of Cromwell’s authority and a series of imminent natural catastrophes that would usher in a reign of everlasting peace. After he was executed for high treason in 1651, other dissidents wrote an account of his last days.

Intrigued, Clarke began to examine the end-time prophesies found in the Biblical books of Daniel and Revelation. His interest in Love’s prophecy led him into Biblical numerology in the hopes of calculating the exact time of the end. Finally, Clarke began preaching the conclusions he had derived from his studies. His enthusiasm rose to such heights that he let his beard grow and ran about the streets crying, “Repent! Repent, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand!”

Shortly thereafter, a free mulatto named Philip John told members of the black community that he had seen a vision in which the whites were to be overthrown. Philip John was tried, whipped and branded for this talk. Then another free black man began fomenting a plot to seize arms and march on the town.

Governor Lyttelton accused Clarke of bizarre behavior, intimating that he was encouraging a violent servile insurrection. This was serious business. In spite of the pleas from a large number of St. Philip’s parishioners, the vestry and the churchwardens, Clarke resigned in February 1759. The vestry gave him the following testimonial: “These are to certify that the Rev. Richard Clarke, who has performed the duties of the Rector of St. Philip’s Church, in Charlestown, South Carolina, for upwards of five years has behaved himself with gravity, diligence and fidelity becoming his office and character.” 146

Clarke returned to England and was appointed lecturer of Stoke Newington and, afterward, of St. James, near Aldgate, in London. In 1768, he was curate of Chestnut in Hertfordshire. He operated a boarding school in his home. Henry Laurens sent his sons, John and Harry, there; by 1772, there were six Charlestonians among Clarke’s twelve students.

Laurens started having grave misgivings, however, after hearing about the lax conditions at the school. Clarke allowed the older boys to roam the streets of London and neglected making them study. He no longer read the Bible to his family or his pupils and did not encourage them to read it independently. Laurens eventually removed his sons from the school and sent them to Geneva to continue their education.

All the while, Clarke was becoming more and more oblivious to this world and spent his time calculating the arrival of the next. During the remainder of his life, he wrote many books, tracts and epistles espousing his theories. He identified himself on the title pages of his books as the late minister of St. “Philips,” Charlestown, South Carolina.

A happier outcome of the Acadian tragedy can be found in an account in Exile Without an End: Acadian Exiles in South Carolina by Chapman J. Milling, a descendant of Pierre La Noue, a “young scion of a noble Huguenot family in France.”

During the Reformation, La Noue reverted to Catholicism and settled in Port Royal Acadia (Nova Scotia) in 1667. His granddaughter Marguerite La Noue, a widow with five children, suffered deportation by the British and arrived in Charles Town in 1756. Shortly after their arrival, Pierre and Gregoire, the eldest brother, escaped Charles Town in an attempt to return to Acadia. Marguerite La Noue and her son François died of “strangers” fever at the plantation of a Mr. Vanderhorst. Her orphaned sons, Basile and Jean-Baptiste, were separated, with Jean-Baptiste being “adopted” by the owners of Vanderhorst plantation. He became an Episcopalian and died in Charles Town in 1781 at the age of forty-two.

Henry Laurens met young Basile La Noue and had him trained as a tanner. Basile taught the trade to his brother. Laurens’s daughter, Martha Laurens Ramsay, wife of Dr. David Ramsay, was a deeply religious woman who took an interest in Basile. Through her influence, the La Noue brothers became Protestants. In time, Basile changed the family name from “La Noue” to “Lanneau.” He joined the Huguenot Church, where he was an influential elder for many years and served three times in the South Carolina legislature. Jean-Baptiste joined St. Philip’s Church.

The Lanneaus were one of the few French Canadian families who prospered in South Carolina. Basile had a successful tannery business and purchased numerous local properties. In 1788, he acquired city lots in the easternmost section of Harleston Village on Pitt Street, where Lanneau descendants built four houses after the Revolution. 147

After he lost his entire family (a wife and five children) in a yellow fever epidemic, Basile returned to Nova Scotia and found the widow of his brother Amand, who had returned from exile. He persuaded the widow to let her children, Pierre and Sarah, accompany him back to Charles Town. Their descendants are still in America, Chapman Milling among them. Basile and his second wife are buried next to each other behind the Circular Congregational Church.

St. Philip’s Church dominates the skyline in this 1774 view of Charleston. Detail from a painting by Thomas Leitch, engraved by Samuel Smith. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

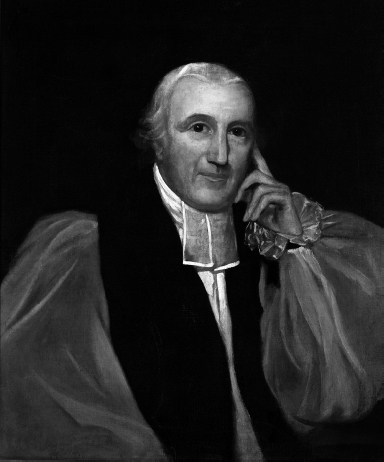

ROBERT SMITH

Robert Smith was born in the parish of Worstead, County Norfolk, England. He was sponsored by William Mason, a Member of Parliament, to be educated at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. After his graduation at age twenty-three, he was ordained by the bishop of Ely. After the resignation of the associate rector of St. Philip’s Church, at Mason’s recommendation, Smith was sent to Charles Town in 1756. He was twenty-five years old. 148

By then, the controversies stirred by the visits of George Whitefield and John and Charles Wesley were just discordant memories, and Commissary Garden had left a growing and prosperous church for his successor.

With the Reverend Charles Martyn as partner, young Smith was soon offering lectures on natural and moral philosophy. He assumed directorship of the Free School and began his work as an educator and pastor to a large flock. He became the rector of St. Philip’s when the Reverend Richard Clarke resigned in 1759. 149

Robert Smith was married three times. His first wife was Elizabeth Paget, the daughter of John and Constantia Hassel Paget. It is a local tradition that Elizabeth had seen Robert Smith from her house on the Bay when he first arrived in Charles Town and decided then and there that he was the man she wished to marry. And marry him she did. Elizabeth brought to the marriage Brabant, a plantation of nearly three thousand acres on the Cooper River that she had inherited from her father. She also provided an entry into the inner circle of Charles Town society, for she had many influential relatives in the community. Among them was her great-uncle Gabriel Manigault, a highly respected businessman who was reputed to be the wealthiest merchant and private banker in the province. 150 (See Appendix E for a brief biography.)

Their marriage came at a time when the British government was making life more and more difficult for the colonists by permitting them less and less control of their local government. Men were beginning to realize that they had to make the difficult choice between loyalty to a distant king and their friends and fortunes in the colonies. Robert Smith seems to have made his decision slowly, but Gabriel Manigault had signaled his leanings in 1760 when he refused appointment to a special Governor’s Privy Council created for the express purpose of easing frictions. Both Smith and Manigault were to pay heavily for their loyalty to the colonial cause. 151

The Smiths led a busy life. As rector of St. Philip’s, Smith was accepted not only as the spiritual leader of the largest church in the colony but also as a generous benefactor. He was able to use his considerable personal talents and his wife’s wealth to great advantage for the rest of his life. Gabriel Manigault was also generous with his well-earned funds. He participated in civic affairs and sometimes helped Smith with the Negro School.

After ten strenuous years, Robert and Elizabeth Smith were both in ill health. They had survived the whooping cough epidemic of 1759, followed by a smallpox epidemic brought back to the city by Governor Lyttelton’s troops after his rash expedition against the Cherokees at Fort Prince George. According to the Gazette , more than 75 percent of the city’s inhabitants had been infected with smallpox; seven hundred died in the epidemic. The Smiths lived to see the arrival of inoculations against the pox under the direction of St. Philip’s Dr. James Kilpatrick.

Gabriel Manigault , circa 1794, by Walter Robertson (British, circa 1750–1802), watercolor on ivory. © Image courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association, 1951.004.0001 .

In 1767, Smith requested the vestry’s permission to return to England because his father had died in 1763, and he was anxious to visit his widowed mother. Typhoid fever, malaria, exhausting heat and relentless cold had had their deleterious effects on the Smiths’ health. These were accepted reasons for escape to England, with its healing baths and centers of medicine found in London. In 1767, the vestry granted Smith’s request. 152

Robert Smith did not sit idle during his absence from his parish. He preached on several occasions in and around Bath and found a new assistant rector for St. Philip’s, the Reverend Robert Purcell. Mr. Crallen, Smith’s assistant for less than a year, had resigned just weeks before the Smiths departed for England. He was obviously depressed or deranged, for he had once attempted to throw himself out of the rector’s window. On his voyage back to England, he jumped overboard and was lost at sea. 153

In better health, the Smiths returned to Charles Town in late December 1769, after more than a year and a half abroad. For Elizabeth, the respite was temporary. She suffered a relapse and died on June 11, 1771. It was a difficult loss for Smith. He had been married thirteen years, and Elizabeth had borne no children. He found comfort in his loneliness at Quinby plantation with his neighbor Thomas Shubrick, whom Elizabeth’s mother had married after husband John Paget’s death.

Shubrick had been a ship’s captain who had amassed a fortune from a mercantile business in the city. He was another influential citizen and a member of St. Philip’s Church. The elderly Shubrick proved a close friend and later a close relation. Smith married his daughter Sarah, who was affectionately known as “Sally.” Her mother was a daughter of Jacob Motte and was connected to the Paget, Manigault and Ashby families.

Smith continued to devote time to the Negro School begun by Commissary Garden. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) had sent Dissenter missionaries to the colony, often without proper funding. Its political agitation against the established church caused such controversy that Smith severed ties with the SPG. He continued the Negro School, giving it his personal oversight until the lack of trained teachers forced its closing. He also promoted the Widows and Orphans Society, which was struggling to raise funds from the clergy to alleviate the pitiful plight of clergy widows and children. Under Smith, its membership was enlarged to include members of the community. 154

Meanwhile, discontent with British rule escalated. When the Reverend John Bullman, assistant minister at St. Michael’s, preached a controversial sermon recommending that the congregation stay out of politics, his sermon caused such furor that he was dismissed by the vestry, over the protests of many members. 155

And so it was that the Provincial Congress set apart February 17, 1775, as a day of “fasting, humiliation and prayer.” The members of the Commons House came in procession to St. Philip’s with the silver mace borne before them. Smith preached a “pious and excellent sermon” that received the thanks of the entire body. 156 It was a solemn occasion because members of the Assembly, including Smith, were faced with a very difficult choice. Tempers were hot, for many had maintained ties with family in the mother country and had sworn allegiance to the king. Smith chose the side of the colonials and urged his listeners to put their trust in God and to act with courage.

While most of the Anglican clergy in other colonies were Tories and remained true to the mother church during the Revolution, the reverse was true at St. Philip’s. The congregation was full of prominent Patriots:

Christopher Gadsden was a member of St. Philip’s Church as were his followers William Johnson, Joseph Verree, Nathaniel Lebby, John Hall, Tunis Tebout, William Trusler, Robert Howard, Alexander Alexander, Edward and Daniel Cannon. Other colonial leaders who worshiped in St. Philip’s were Henry Laurens and his son John, Rawlins Lowndes, Colonel Charles Pinckney, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Thomas Pinckney, Edward and Hugh Rutledge, Henry Middleton and his son Arthur, signer of the Declaration of Independence, William Johnson .

Of the principal citizens whom the British later exiled to St. Augustine in violation of their paroles, more than a third were from St. Philip’s: Christopher Gadsden, Thomas Ferguson, Peter Timothy, John Edwards, Edward Rutledge, Hugh Rutledge, Isaac Holmes, William Hasell Gibbes, Alexander Moultrie, John Earnest Poyas, Doctor Peter Fayssoux, Edward McCrady, John Neufville, William Johnson, Thomas Grimball, Anthony Toomer, Robrt Cochran, Thomas Hall, Arthur Middleton, Samuel Prioleau, Jr., Edward Weyman, Henry Crouch, and John Splatt Crips . 157

British Occupation of Charles Town

When the mighty British navy attacked Charleston by sea on June 28, 1776, Smith fought on Sullivan’s Island in a historic engagement now called the Battle of Fort Moultrie. The British were expected to come by sea, and fortifications on Sullivan’s Island were hastily shored up to protect the harbor entrance. (The British also attempted a land assault in a flanking maneuver at the other end of the island. It failed utterly thanks to sharpshooters under the command of Colonel “Danger” Thomson.) When the British fleet arrived, it encountered a crude, unfinished fortification made of palmetto logs reinforced with sand. Smith had joined Moultrie’s troops as a private. In a surprising and stunning Patriot victory, the British navy suffered heavy losses and withdrew. Smith praised the city defenders in a sermon the following Sunday. 158 Less than a month later, Sally Smith died, after only five years of marriage, leaving him with the care of a three-year-old daughter, Sarah Motte Smith. 159

The fortunes of war changed when the British besieged the city in 1780. Once again, Smith reported as a private and was among the citizens who served in city fortifications on Boundary (now Calhoun) Street. Their sacrifices were in vain, for in May, the British captured Charles Town. Lieutenant Governor Bull and other Loyalist officials returned to the city, and British officers, who considered the colonials rebels, forcibly occupied their homes and confiscated, destroyed or stole their belongings, including slaves and livestock. Sir Henry Clinton, Lord Rawdon and General Charles Cornwallis all used the Miles Brewton mansion on King Street as their headquarters. The story about Rebecca Brewton Motte’s hiding her three daughters in the attic while the British officers reveled in her formal apartments is one of Charleston’s most popular anecdotes.

After Charles Town fell, Robert Smith was captured and imprisoned. Protests from General William Moultrie finally led to Smith’s release to serve as chaplain in the hospital. In April 1781, he was transferred to Haddrell Point on Mount Pleasant and imprisoned with other Continental officers. Known as an outspoken patriot, Smith was offered his freedom and property if he would take an oath to the Crown. His reply was, “Rather would I be hanged by the King of England than go off and hang myself in shame and despair like Judas.” 160

In June 1781, Smith was exiled to Philadelphia after he refused to pray for the king of England. While in Philadelphia, he met his third wife, Anna Maria Tilghman (Widow Goldsborough). 161 He remained in the middle states until the peace and took temporary charge of St. Paul’s Parish, Queen Anne’s County, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. His daughter, Sally, apparently stayed with her grandparents during his absence.

While Smith was in Philadelphia, the British hold on the interior of South Carolina significantly weakened. Continental general Nathanael Greene sent General Thomas Sumter, with Francis Marion and “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, to force the British to abandon the Goose Creek area. As the British moved troops from Monck’s Corner, Sumter led nearly one thousand men from Orangeburg. On July 17, 1781, they met on the plantation of Smith’s father-in-law, Thomas Shubrick. Lee’s cavalry overtook the British rear guard at Quinby Bridge. The engagement loosened so many planks on the bridge that the rest of Lee’s and Marion’s men had to march upstream to cross at a ford. The Continentals had arrived too late, for the British were already ensconced in Quinby’s main house and outbuildings; Sumter’s ill-advised assault turned into a costly stalemate. 162

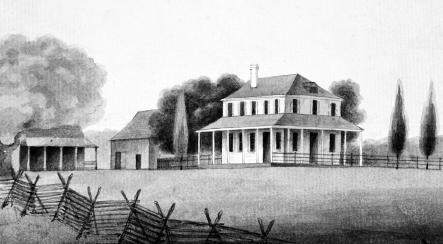

Another View of Brabant: Seat of the Late Bishop Smith , from untitled sketchbook, 1796–1805, circa 1800, by Charles Fraser (American, 1782–1860), watercolor on paper. © Image courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association, 1938.036.0103 .

Smith’s plantation served as temporary Cooper River headquarters for Lord Cornwallis. A Brabant plantation anecdote is still told by guides at St. Philip’s Church. The British heard that the plantation overseer, an Irish immigrant named Mauder, had concealed the church silver somewhere on Brabant grounds. Repeated threats and even three incomplete hangings from a large tree did not succeed in gaining any information from Mauder. Ironically, the hangings occurred from the very tree under which the silver was buried. Mauder later admitted that he would have revealed the hiding place of Smith’s silver, but it was beside that of the church and he was superstitious about betraying the location of the sacred vessels. The silver is still in possession of St. Philip’s.

By January 1782, the British were penned up in Charles Town and surrounded by a combination of militia and Continental soldiers. The situation was desperate. People were starving, and supplies were so low that British commandant Alexander Leslie ordered the slaughter of two hundred horses because there was nothing left to feed them.

To protect the river approach to the city, Leslie had several small outposts guarded by armed galleys. When he received reports that Marion’s spread-out detachments might be vulnerable, he ordered Major William Brereton to invade St. Thomas Parish. The British troops crossed Daniel Island and moved fourteen miles up Strawberry Road, arriving at Brabant at about noon. They found Marion’s men north of Videau’s Bridge and pursued them in a six-mile running gun battle before the British turned back for more foraging in the area.

After the Revolution

St. Philip’s vestry minutes note correspondence assuring Smith that the church would have a place for him. Upon his arrival, he was met with a rousing welcome from friends and quickly resumed his duties at the church. Members of his congregation had suffered great financial losses due to theft and destruction by the British, Smith among them. He was forced to redouble his efforts in many areas.

One of the ways he raised money was through the “Academy,” which later became the College of Charleston. Smith held the first classes of the Academy at his residence on Glebe Street. 163 He later relocated the school to an old military barracks located on public land (now the Cistern Yard) that had been granted as part of the 1785 College of Charleston charter. (The college had been founded before the Revolution, but the war delayed its progress, and it was not was chartered until 1785.) The college was rechartered in 1791 because of questions about the 1785 act, and the trustees hired Robert Smith as its first president. Smith spared neither trouble nor expense in obtaining the best-qualified classical teachers. In 1794, the college graduated its first class, which consisted of six students, the oldest being eighteen.

It was due to Smith’s able leadership that the school was accepted in Charleston. According to a government publication, work for a degree was considered so easy that one of its first graduates said that “the whole thing was absurd.” Upon Smith’s resignation in 1797, the school declined, and in less than fifteen years it had closed completely. The college was revived in 1824 with the hiring of the Reverend Jasper Adams from Brown University. 164

The Right Reverend Robert Smith, First Bishop of South Carolina , oil, circa 1796, by James Earl, on display at the Edmondston Alston House, Charleston, South Carolina. Courtesy of Middleton Place Foundation, Charleston, South Carolina .

In 1785, as a result of Smith’s “unwearied exertions of his sound and judicious zeal,” church members met at a state convention from which delegates were sent to Philadelphia to participate in the organization of the Protestant Episcopal Church in America.

In 1789, Smith was a deputy at the seventh state convention and later attended the first General Convention in Philadelphia. While there, Smith received a Doctor of Divinity degree from the University of Pennsylvania. 165

The Reverend Robert Smith was elected bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South Carolina in 1795 at the second General Convention in Philadelphia. He was consecrated the sixth bishop in the American succession by Bishop White at Christ Church, Philadelphia, on September 13. 166

The church was held in very low esteem in South Carolina after the Revolution. In addition to theft of goods, property and slaves, the British had devastated the countryside. Parish churches—with the exception of St. James Goose Creek, which had a royal coat of arms—were desecrated, burned to the ground and left in ruins. As a result, Smith was a low-profile administrator who worked primarily within the St. Philip and St. Michael Parishes. He never performed confirmations or consecrations because the parishes never invited him to do so.

Smith worked tirelessly until he died after a few days’ illness in 1801. He was buried in the east side of St. Philip’s Churchyard beside his family. The May 4, 1802 inventory of his estate lists the names of 122 slaves on Point Comfort plantation and 79 slaves on Brabant plantation.

In the 1920s, the church chancel was extended east, and Smith’s grave site beneath the altar was rediscovered. His memorial slab was moved and now rests on the outside of the church. His remains were undisturbed and are now part of the foundation of the new altar. In 1994, a marble memorial to Bishop Smith was dedicated at the foot of the altar rail steps.

Bishop Smith’s Sermons and Prayer Book

St. Philip’s is in possession of Bishop Smith’s 250 handwritten sermons and his prayer book. They are among the valuable papers in St. Philip’s archives. The prayer book is a copy of the 1762 Church of England Book of Common Prayer and contains changes carefully ruled out in red ink that were made at the general conventions in Philadelphia. For example, prayers for the royal family were changed to prayers for the president of the United States and the Congress.

The volume is large and heavy. On the flyleaf is the signature of Bishop Smith, followed by an inscription: “The Gift of His Excellency Thomas Boone Esquire to the Parish Church of St. Philip, Charles Town So. Carolina Anno Domini 1762.” Below appears the signature “The Right Rev’d Bishop Smith.”

Another hand records on the flyleaf, “This book was purchased from the heirs of the Rev. Dr. Purcell in New York in 1845 or 1846 by Mrs. Swords (?) TS Comford (?), and by them sold to C E Gadsden, who asks leave to deposit it in the Library of Edward L. Laurens Esq. Charleston July 8, 1846.” A notation from April 1852 reads, “The Rev. Cranmore (?) Wallace was requested by Mr. Laurens to deposit this volume in the Library of the Society for the Advancement of Christianity in So.Car.” Another notation reads, “St. Andrew’s Day 1909 Returned to the Rectory of St. Philip’s by the Advancement Society.”

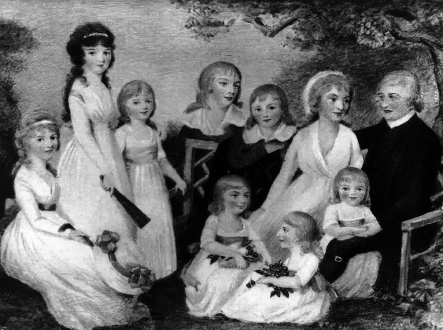

THOMAS FROST

Thomas Frost was born in 1759 at Pulham, near Norwich in the County of Norfolk. He graduated from Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, in 1780. He was chosen a fellow of that college and was ordained a deacon on March 11, 1781, by Dr. Yonge, bishop of Norwich, and was ordained a priest by Bishop Bagot of Norwich on June 6, 1784. Afterward, he served as curate in the parishes of Ingham and Hedderly in Norfolk. He was much beloved by his English parishioners, especially the poor, to whom he was a cheerful giver. Frost’s prospects for advancement in the Church of England were good, but he chose to come to America to be the assistant at St. Philip’s Church at the invitation of his friend Robert Smith.

Frost and Robert Smith had met at Cambridge. Frost, the younger man, had the nickname “Jolly,” and Smith was described by contemporaries as “merry,” so they must have gotten along well. Frost arrived in Charleston in 1785 and was approved as Smith’s assistant the following year. Frost was active in helping him restore the damage left by the British after the Revolution and in ministering to the combined parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael.

At Smith’s death in 1801, Frost became rector, serving a total of eighteen years at St. Philip’s. He was as diligent in the discharge of his duties at St. Philip’s as he had been in England: “The sick and the needy of his cure received excellent attention and many esteemed his council. As a preacher he was animated, unaffected, and engaging: tender in reproof, fervent in exhortation, and in remonstrance. He was remarkably accessible to all classes and ages; and loved to resolve the doubts of the wavering, and to confirm the feeble-minded. Such was the cheerfulness of his temper, and the agreeable case of his manners, that even to the young, religion appeared in him as persuading, not commanding.” 167

When Frost became rector, the Reverend Peter Manigault Parker became the assistant minister. Parker was born in Charles Town just before the Revolution and graduated from Yale College in 1793. He pursued his ministry studies in New York under the superintendence of Dr. (afterward Bishop) Moore and was ordained a deacon in 1795 by Bishop Prevost in the Diocese of New York. Upon his return to Carolina, he was the curate of St. John’s Berkeley from 1796 until he resigned to become assistant minister of St. Philip’s. He went to New York and received priest’s orders from Bishop Moore in June 1802. He returned immediately to Charleston but unfortunately died of bilious fever in July of that same year. 168

Family tradition suggests that Thomas Frost met his future wife, Elizabeth Downes, on the voyage to his new assignment. They were married in 1787. She was a Charles Town native who had spent her girlhood abroad, having left with her family not long before the Revolution. Her father, Richard Downes, was a wealthy merchant. Her mother, Mary Ashby, was the daughter of John and Christiana Broughton, and she was a granddaughter of the Reverend Francis LeJau. 169

On January 20, 1804, Frost was a delegate from St. Philip’s to the Seventeenth Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South Carolina, which was held for the express purpose of appointing a Standing Committee conformable to the constitution of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States of America. He died six months later, leaving behind a widow with six children to support. 170

Trinity Primitive Methodist Church

The story began in 1791 when the Methodist Episcopal Church was holding its annual general conference at its first mission house, located diagonally across from St. Philip’s, on the corner of present-day Cumberland and Meeting Streets.

Bishop Francis Asbury, the first American Methodist Bishop, was in Charleston to appoint missionaries and receive reports about the Carolina missions. Bishop Thomas Coke, who was in charge of expanding foreign missions, was expected to arrive from Jamaica and was en route. Unbeknownst to Asbury, Coke was accompanied by the Reverend William Hammet (sometimes “Hammett”), a charismatic Irish shoemaker who had converted to Methodism. Hammet had been ordained in 1786 by John Wesley and had joined Bishop Coke shortly thereafter.

Coke had taken Hammet to Jamaica, where the latter was remarkably successful. He started several small churches as well as a large church in Kingston, with a growing congregation composed mostly of slaves. When the number swelled to 1,500, they built a church in the waterfront area of downtown Kingston. This caused the white islanders to react violently. During his sermons, Hammet was pelted with all manner of refuse, and there were protests, death threats, riots and acts of arson.

The bishop returned to Jamaica eighteen months later only to find Hammet an emaciated, ill and exhausted man. Coke decided to take him to Charleston. Unfortunately, their little craft ran into severe weather off Edisto Island, and by the time they arrived, Bishop Asbury had already appointed the local missionaries. The Reverend James Parks was made pastor of Cumberland Methodist Church, and the Reverend Philip Mathews was to serve in Georgetown. Asbury then left Charleston and continued on to Philadelphia.

As Hammet’s health had improved on the trip, he was invited to address the Methodist congregation. The audience responded enthusiastically to his emotional, flamboyant style. Hammet became enchanted with the new mission, and Charlestonians accepted him as a hero and swooned at his feet. Convinced that he was the right minister for the church, Hammet pursued Asbury to Philadelphia and on to another conference in New York before he was able to persuade the reluctant Asbury to appoint him co-pastor with Parks.

Hammet was disappointed with second place and refused the appointment. He returned to Charleston and published pamphlets and articles in the paper claiming that “Asbury Methodism” had departed from Wesley’s “original plan.” A war of words began in the local press, where Hammet expressed his opposition to the very existence of bishops and their authority over ministers. He also severed all connection with Asbury, Coke and the American Conference and proceeded to begin a denomination of his own. When word of Hammet’s disruptive behavior reached England, the British Methodist Conference broke all ties with him; Wesley also disowned him.

One-third of the Methodist congregation left Cumberland Church and began to attend Hammet’s services in the new city market. Within a short time, Hammet had such a large audience that he had built a church at the corner of Wentworth Street and Maiden Lane. The first service was held in August 1792. Later, a two-story parsonage and other buildings were added to the site. The church property was called the Primitive Methodist Church and was owned solely by Hammet.

In the meantime, Philip Mathews, a close friend of Hammet, had joined the new denomination. Both Mathews and the Reverend William Brazier had been Hammet’s associate missionaries in Jamaica. Brazier stayed in the Primitive Methodist Church parsonage and performed the service when Hammet married Catherine Darrell in 1794.

Mathews soon had a falling out with Hammet, parted company and returned to the Anglican church. The Primitive Methodist denomination did not survive long either. Hammet’s quick temper and autocratic rule alienated his clergy and congregation, and in spite of his oratory, numbers dwindled.

William Hammet died in 1803 and was buried in the Trinity Primitive Methodist Churchyard. His wife died the next year and was buried beside him. The church building on Maiden Lane was Hammet’s personal property, and he willed it to the Reverend William Brazier.

By then, Brazier had changed careers and was a practicing doctor in Edgefield, South Carolina. After being informed of Hammet’s death, Brazier quit his practice, moved into the empty parsonage and spent nine difficult months trying to be a minister again. Neither he nor the congregation was happy with the arrangement. Brazier contacted Asbury about the possibility of giving the property to the Methodists, but the response was so slow that he put the building up for sale.

These events coincided with the Reverend Thomas Frost’s desire to alleviate the overcrowding of St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s Churches. With Philip Mathews as agent, the Frosts borrowed money from John Vicars, a member of St. Philip’s, and bought the Trinity Primitive Methodist Church for a third Episcopal church.

The trustees of Trinity Primitive Methodist Church were furious when they learned of the purchase through the Gazette . Pews had already been rented to Episcopalians, and the consecration service was announced for Sunday, June 27, 1804, with the Reverend Frost giving the sermon. Bedlam ensued.