Part III

THIRD ST . PHILIP ’S CHURCH

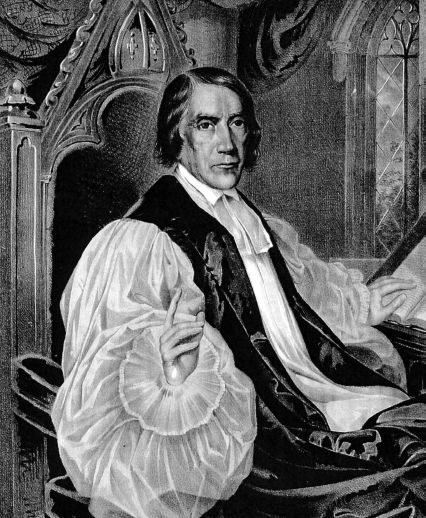

CHRISTOPHER EDWARDS GADSDEN

Christopher Edwards Gadsden, grandson of Revolutionary War hero General Christopher Gadsden, became the rector of St. Philip’s Church following the death of James Dewar Simons in 1814. At that time, Gadsden had already served as assistant minister for five years.

A native Charlestonian, Gadsden was born in 1785, the eldest son of Phillip Gadsden and Catherine Edwards Gadsden. As a youth, he attended both St. Philip’s, his father’s church, and the Congregational church of his mother. In his early years, he was educated in Charleston at the “Associated Academy.”

In 1802, Gadsden and his brother, John, went to Yale College, where he entered the junior class. At Yale, he became a close friend of John C. Calhoun, and they remained friends throughout Calhoun’s lifetime. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1804, Gadsden returned to South Carolina and studied theology. He was ordained deacon in 1807 by Bishop Benjamin Moore at St. Paul’s Chapel, New York. After a short stint at St. John’s Berkeley, he became assistant rector at St. Philip’s in 1810 and was ordained a priest several months later by Bishop Madison of Virginia. Gadsden became rector of St. Philip’s in 1814.

In 1816, Gadsden married Eliza Bowman, who died childless in 1826. Four years later, he married Jane Dewees, by whom he had eight children, four of whom died young. 186

By the time Gadsden became rector of St. Philip’s, the congregation had swelled to more than 500 members (340 white and 190 black), with 200 children in the Sunday school. The church was flourishing, and new pews had to be installed to accommodate the growing number of parishioners.

The Right Reverend Christopher Edwards Gadsden, fourth bishop of South Carolina. Courtesy of the St. Philip’s Episcopal Church Archives .

Exclusive of Gadsden’s duties as bishop of South Carolina, noteworthy events that occurred while he was at St. Philip’s include the Denmark Vesey conspiracy, the fire of 1835, church expansion and the burial of John C. Calhoun at St. Philip’s Churchyard.

Denmark Vesey’s Failed Insurrection in 1822

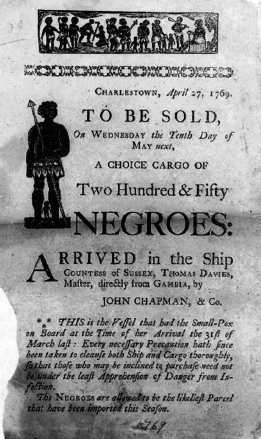

Contemporary advertisement. Courtesy of the Library of Congress .

Denmark Vesey is thought to have been born in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. He was owned by Joseph Vesey, a sea captain from Bermuda. Vesey sold young Denmark to a plantation owner, who forced Vesey to take him back because epileptic fits rendered Denmark “defective.” Interestingly, the epileptic fits are said to have stopped once he was removed from the hard labor at the sugar plantation.

Joseph Vesey owned at least five ships that transported molasses, lumber, rum, meat, gin and other food products. He was also a slave trader. The captain took young Denmark on slave trading expeditions to Africa, where he was able to observe the slave hunters, the slaves and the terrible voyages across the Atlantic. Joseph Vesey earned a fortune and retired to Charleston, where he became a respectable merchant dealing with ship’s supplies. In Charleston, he hired his young chattel out as a carpenter. In 1799, Denmark won a city lottery and bought his freedom.

In 1817, Denmark Vesey attended Hampstead African Methodist Episcopal Church, which white authorities temporarily shut down in 1818 and again in 1820. 187 Angry at the closing of his church, Vesey began plotting a rebellion scheduled for Bastille Day, July 18, 1822. Vesey and his followers planned to execute all whites and the slaves who sided with their masters, liberate the city’s slaves and sail to Haiti to escape retaliation. The plans were revealed by a slave belonging to Colonel J.C. Prioleau. The militia was called out and rounded up the suspects. After a closely guarded trial, Vesey and the other black leaders were hanged on Boundary (now Calhoun) Street. 188 John Wroughton Mitchell, superintendent of St. Philip’s Church for seventeen years and city attorney, was a part of these proceedings, according to one descendant’s account. 189

Fire!

On June 13, 1796, a major fire started in a stable in Lodge Alley, near the French Huguenot Church, and fanned by a high east wind, it raged unchecked for twelve hours. It left hundreds of people homeless. With fire wells empty and hand-pumped engines useless, firemen began blowing up buildings with gunpowder to make gaps in the flames. The Huguenot Church nearby was one of those buildings. 190 As the fire neared St. Philip’s, a young slave belonging to Charles Lining braved the flames, climbed up to the burning shingles and ripped them off the building. He was hailed a hero, and St. Philip’s later purchased him from Lining for $700 and gave him his freedom.

St. Philip’s also survived the Fire of 1810, but unfortunately, it did not survive a lesser fire that occurred in 1835. The Courier described the February 16 disaster:

The most striking feature of this calamity is the destruction of St. Philip’s Church, commonly known as the Old Church. The venerable structure which has for more than a century (having been built in 1723) towered among us in all the solemnity and noble proportions of antique architecture, constituting a hallowed link between the past and the present, with its monumental memorials of the beloved and honored dead, and its splendid new organ (which cost $4,500), is now a smoking ruin. Although widely separated from the burning houses by the burial ground, the upper part of the steeple, the only portion of it externally composed of wood, took fire from the sparks which fell upon it in great quantities. It is much to be regretted that preventive measures had not been taken in season to save the noble and consecrated edifice. The flames slowly descending wreathed the steeple, constituting a magnificent spectacle and forming literally a pillar of fire, and finally enwrapped the whole body of the church in its enlarged volume. The burning body of the Church was the closing scene of the catastrophe. In 1796 it was preserved by a negro man who ascended it and was rewarded with his freedom for his perilous exertions, and again in 1810 it narrowly escaped the destructive fire of that year, which commenced in the house adjoining the Church yard on the north .

Burning of St. Philip’s Church , by John Blake White, 1835. Note Bishop Gadsden being cared for on the ground in the lower-left quadrant of the painting. The church tradition of his fainting at the sight of the fire was confirmed when the painting was recently restored. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

We have been informed that the only monument of the interior of the Church which was not totally destroyed is one that with an accidental appropriateness bears the figure of grief . 191

According to church tradition, Bishop Gadsden fainted at the sight of the fire. The Holy Table was saved from the old church as it was still burning. At the time of the fire, Daniel Cobia was St. Philip’s assistant minister. His expressed the feelings of desolation caused by this event in a memorable sermon entitled “The House of God in Ashes.”

The sense of loss lingered at least a generation. Fifty years later, on August 9, 1874, the Reverend John Johnson, then rector of St. Philip’s Church, preached about the fire at the 150th year commemoration of the occupation on the same site:

It is his [Dr. Gadsden’s] ministry also which really bridges over a great chasm in the history of the Parish. I mean the destruction of the Old Church building erected in the middle of the western church yard. Dr. Gadsden had been your Rector for twenty-one years, when on that fatal Sunday morning in February, of the year 1835, the flakes of the fire from the north of us caught the dry wood work of our steeple, and the flames descending wrapt the Church of so many consecrated affections, until despite all efforts “our holy and once beautiful house where our fathers praised God was burned up with fire, and all our pleasant things laid waste.”

It is not too much to say that never before or since in the history of this city has the loss of a public building been attended with more poignant sorrow and mourning than that of old St. Philip’s Church. To show how general was the feeling in our community, our congregation had places of worship offered them by many of their fellow Christians of all dominations. And one occurrence during the fire was made the subject of some lines by, it is thought, Mr. Charles Fraser, once an honored citizen, but not of our flock .

I can remember only the spectacle of the burning at a distance, and the sounds of grief that were close by me as I watched the flames, but knew not how to estimate in my childhood such a loss .

Men talked of speedily replacing it, but it could never be done; in its most sacred associations and its time hallowed adornments we knew there could be but one “Old St. Philip’s.” Such losses laugh to scorn insurance money. Such ruins when they fall shake the very ground of our lives, and strew with ashes our bruised and desolated hearts. How while the ruins were still smoking on that Sunday morning the afflicted flock were gathered by their Shepherd, as well they could be, in the old Sunday School building to the east of us, and how to a weeping congregation he preached Christ’s own message of comfort and consolation . 192

The fire had occurred just before the great financial panic of 1837, and Charleston’s economy was in a depressed state. St. Philip’s was likewise affected by the depression. The vestry stated in 1835 that income from leases of the buildings on the Glebe lands had expired, and it was obliged to pay for improvements. In addition, a depreciation of the property and the land caused the Glebe holdings to lose so much value that some buildings could not be sold for the sums that the vestry had paid for the buildings alone. Public aid for rebuilding the church was denied because the congregation was a rich corporation. In spite of numerous setbacks, funds to rebuild were raised. On November 12, 1837, the cornerstone of the new building was laid amid appropriate ceremonies. 193

After the fire, the city attempted to widen Church Street by having St. Philip’s porticos and steeple moved east. The vestry maintained that a fine steeple was more ornamental than a wide street. In the end, a compromise was worked out, with the street continuing to curve around a tower and the projecting porticos. 194

The vestry asked architect Joseph Hyde to rebuild the church exactly as it had been. However, he persuaded the members to replace the massive interior Tuscan columns with lighter Corinthian columns after the style of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London. The new church was built of brick on the same foundations, except for an extension of twenty-two feet eastward (the chancel end). Modifications from the original church included the following:

The floor was raised above the ground about three feet; steps of stone being used to ascend to the three porches at the west end of the building, and to the two doors central on the side walls; a chancel, recessed about fifteen feet, and lightened with a wide and lofty window, proved an important addition to the interior; the two side-aisles were put immediately next to the side walls; one hundred and two pews on the floor provided five hundred and fifty sittings, while thirty-six in the galleries, reached by stairs in the vestibule, provided two hundred and fifty more, making accommodations, without crowding, for upwards of eight hundred persons . 195

The new church was consecrated by Bishop Bowen on November 9, 1838. Ten years later, Edward Brickle White, a communicant of St. Philip’s, designed a two-hundred-foot spire in the English Renaissance steeple style, in the Wren-Gibbs tradition. The $84,206.01 cost of the new church was reported to the congregation in July 1839. James P. Welsman donated an organ, which was made in London at a cost of $3,500. The subsequent cost of erecting a steeple raised the total to nearly $100,000. 196

Church Expansion

In 1847, Colin Campbell, Esq., of Beaufort presented to St. Philip’s a chime of bells and a musical clock, and plans were made to build the steeple to accommodate his generous gift. The steeple was built by a Mr. Brown. There were eleven bells, the largest weighing five thousand pounds. The clock chimed the hours and quarters and, at three different intervals in twenty-four hours, “Welcome Sweet Day of Rest,” “From Greenland’s Icy Mountain” and “Home Sweet Home.”

A new Sunday school house was added in the rear of the church in 1850. Over the door, it had the inscription, “Feed My Lambs.” The church bought a piece of land north of the western cemetery for a parochial school. Bishop Gadsden’s last appeal was for funds for this building. 197

John C. Calhoun’s Final Resting Place

Bishop Gadsden had been Calhoun’s classmate at Yale and enjoyed a closed association with him. When former Vice President and sitting U.S. Senator John C. Calhoun died in Washington, on the last day of March 1850, the National Intelligencer published the following on Wednesday, April 3:

The two Houses of Congress were yesterday engaged in the performance of funeral rites over the remains of the Hon. John C. Calhoun, and the Senate chamber presented a solemn and deeply interesting aspect. The corpse of the deceased Statesman—enclosed in a metallic case, bearing the following simple inscription on the plate: “John C. Calhoun: born March 18, 1782; died March 31, 1850”—was placed on a bier in the centre area, around which were grouped relatives and friends, amongst whom were a son of the deceased, the surviving Senator and the Representatives in Congress from South Carolina, and veteran statesman as pall-bearers, some of whom have been Mr. Calhoun’s contemporaries during the many years he has been in the National Councils—Mr. Clay and Mr. Webster, Mr. Mangum and Mr. Cass, Mr. Berrien and Mr. King. The other members of the Senate, in two semi-circular rows of seats, enclosed the melancholy group .

The President of the United States was present, seated on the right of the Vice President, and the Speaker of the House of Representatives occupied a chair on his left. The Chaplains of the Senate and House of Representatives occupied the Secretary’s desk, to the right and left of whom were the Secretary of the Senate and the Clerk of the House, and immediately in front were the Committee of Arrangements. The subordinate officers of the two Houses were in appropriate positions around the platform .

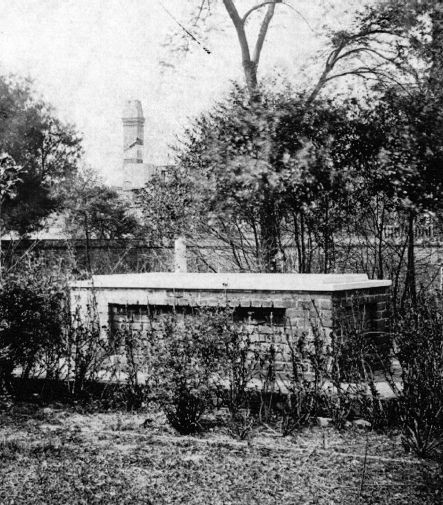

Old Sunday school building, restored as a chapel after the tornado of 1938 thanks to the generosity of Miss Eugenia Frost. The marble top of John C. Calhoun’s original grave is imbedded in the foundation on the south side of the building. Courtesy of the Library of Congress .

The Chief Justice and Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, and its officers, in their robes, and two of the Judges of the United States Court for the District of Columbia, were assigned seats in the chamber on the extreme left of the Presiding Officer, and the extensive Diplomatic Corps were on the right. The Members of the House of Representatives, with the Heads of Departments, occupied the residue of the body of the chamber, leaving the outer circle behind the bar for Officers of the Army and the Navy. Ex-Cabinet officers, Senators, Members of the House of Representatives, Mayor and Councils of Washington, Heads of Bureaus, and other civilians entitled to admission, were accommodated beneath the marble gallery and in the adjacent aisles .

The circular gallery was exclusively appropriated to ladies, leaving only the limited space in the marble gallery behind the Reporters for such male spectators as could gain admittance .

The Service performed was that of the Episcopal Church, of which the Chaplain to the Senate, the Rev. C.M. Butler, is a Minister. The ritual, commencing with “I am the Resurrection and the Life,” was followed by a Sermon, brief but impressively appropriate, from Psalm 82, 6 and 7: “I have said ye are gods; and all of you are children of the Most High. But ye shall die like men and fall like one of the princes.” The funeral cortege left the Senate chamber for the Congressional Burial Ground .

The Charleston City Council unanimously passed a resolution to ask for the distinction of being Calhoun’s final resting place because of his close connection to the commonwealth of which Calhoun was “the greatest product.” 198 The mayor contacted Calhoun’s family, and they agreed with the request.

Calhoun’s body was brought to the city amid great pomp and circumstance. The funeral cortege left Washington in a black-draped vessel. Mournful crowds lined the waterway as the ship passed by. The vessel stopped at Richmond before it proceeded down the east coast to Charleston.

Not to be outdone by the nation’s capital, Mayor T. Leger Hutchinson declared April 25 a day of mourning. The Mercury noted that the ceremonies absorbed the whole thought, soul and presence of the city. Charleston was as one gigantic house of mourning. All business was suspended when Calhoun’s body arrived. The citizens had shuttered their windows in respect. It was a silent, somber city.

The funeral cortege disembarked at Calhoun Street and marched the coffin down to the old Citadel (then located on Marion Square on the north side of Calhoun Street) and from there on to Broad Street, where Calhoun’s body was laid in state in city hall. Free passage on the railroads brought crowds from across South Carolina to join the local mourners, who passed the raised bier and threw flowers under the casket.

St. Philip’s Churchyard was designated as a temporary resting place, and the funeral the next day was a grand climax to the historic event. Both the Mercury and the Charleston News and Courier took the day off from publishing, but not without first spending considerable attention on the elaborate arrangements:

At 10 o’clock [April 26] a civic procession under the direction of the Marshal, having been formed, the body was then removed from the catafalque in the City Hall and borne on a bier by the guards of honor to St. Philip’s Church: on reaching the Church, which was draped in the deepest mourning, the cortege proceeded up the central aisle to a stand covered with black velvet, upon which the bier was deposited. After an anthem sung by full choir, the Right Reverend Dr. Gadsden, Bishop of the Diocese, with great feeling and solemnity, read the burial service, to which succeeded an eloquent funeral discourse by the Rev. Mr. Miles. The holy rites ended, the body was again borne by the guard of honor to the western cemetery of the Church to the tomb erected for its temporary abode, a solid structure of masonry raised above the surface and lined with cedar wood. Nearby, pendant from the stall spar that supported it, drooped the flag of the Union, its folds mournfully sweeping the verge of the tomb as swayed by passing wind, enwrapped in the pall that first covered it on reaching the shores of Carolina. The iron coffin, with its sacred trust, was lowered to its resting place, and the massive slab, simply inscribe with the name “Calhoun” adjusted to its position . 199

It was later decided that Calhoun’s remains be kept permanently in Charleston. During the War Between the States, it was feared that if the city fell, his body would be desecrated. The tomb was secretly opened, and the coffin was removed to the East Churchyard near the chapel. When it was safe, it was quietly restored to the original tomb.

In December 1883, Representative Charles Inglesby, a member of St. Philip’s Church, introduced a joint resolution in the South Carolina legislature appropriating funds for erecting an imposing sarcophagus over the grave. The resolution was passed unanimously.

The original “Calhoun” marker was fixed in a horizontal position against the south wall of St. Philip’s Sunday school building, in the northeast corner of the eastern cemetery, and bears the inscription, “This marble for thirty-four years covered the tomb of CALHOUN in the Western Churchyard. It has been placed here by the Vestry, near the spot where his remains were interred during the Siege of Charles Town, from which spot they were afterwards removed to the original tomb, and subsequently deposited under the Sarcophagus erected on the same site in 1884 by the State.” A magnolia tree was planted on the western side of the sarcophagus. Evergreen, it was to be a reminder of Calhoun’s enduring reputation and the undying affection of the people who were most dear to him. 200

John C. Calhoun’s original grave site. Courtesy of the Library of Congress .

Sarcophagus over John C. Calhoun’s grave. Erected in 1884, it was funded by a joint resolution in the South Carolina legislature. This 1904 photograph shows Calhoun’s grave and a magnolia tree planted nearby. Courtesy of the Library of Congress .

Christopher Gadsden Becomes Fourth Episcopal Bishop of South Carolina

Bishop Robert Smith’s death in 1801 seems to have stunned the diocese, for no effort was immediately made to replace him. A reorganizing convention was held in 1804, but efforts dragged on. Theodore Dehon, rector at St. Michael’s, became the second bishop of South Carolina in 1812, eleven years after the death of Bishop Smith. Dehon began the restoration of the devastated church buildings that the British had left behind when Loyalist troops evacuated the state.

In his first annual address, Bishop Dehon emphasized the importance of confirmation and explained why none had occurred for some time. He confirmed 516 people in 1813, and through his efforts, plans to establish a General Theological Seminary in New York were begun at St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s, with the enthusiastic support of Christopher Gadsden, then rector of St. Philip’s.

Bishop Dehon died of yellow fever in August 1817. His son, William Dehon, was born the following month and grew up to become rector of St. Philip’s Church, where he served until 1862. Following the bishop’s death, his wife, Sarah Russell Dehon, moved back into her family home at 51 Meeting Street (the Russell House), where she reared their three children and was active in the community. 201

Bishop Dehon was succeeded by Nathaniel Bowen, former rector of St. Michael’s (1810–17). When Bowen died in 1839, there was a dispute over who would become South Carolina’s next bishop. After some controversy, Christopher Gadsden was elected bishop the following year. Gadsden had reservations about whether he would unite or divide the diocese over the question of revivalism. The laity had voted for him by a large majority, but the clergy had given him only a one-vote majority. Gadsden urged the clergy to unite behind another candidate. After an overnight delay and consultation with the clergy, the vote the following day was unanimous. Gadsden was consecrated thirty-fifth bishop in the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States and fourth bishop of South Carolina in Trinity Church, Boston, in 1840. 202

Gadsden’s first act as bishop of South Carolina was confirmation of 126 persons at St. Michael’s Church. It was the custom at that time for all candidates in the Charleston churches to be confirmed in one location that was rotated among the different Episcopal churches. This class was from six congregations. 203

Gadsden was active in expanding the membership of the Episcopal Church in South Carolina, usually visiting each congregation once a year. He considered evangelizing to the black residents in the diocese, both free and slaves, of utmost importance. 204 He also traveled to Georgia and Florida, and in 1843, he visited St. Augustine, where his grandfather Christopher Gadsden had been imprisoned during the Revolution. In 1851, he presided at the consecration of the Reverend Francis H. Rutledge to be bishop of Florida. 205

In 1847, Gadsden addressed the subject of building churches for different economic strata and noted that the experiment of separating the rich from the poor had not been a success, stressing the fact that people should worship together. 206 Proper vestments for the clergy were another hot topic, 207 as was preaching the gospel to Indians, who were being removed from their ancestral lands to free up land for white settlers. Missionary zeal was evident, and aspirations extended to sending clergy as far away as China. 208

Bishop W.S. Perry wrote that Gadsden’s episcopate was “marked by growth and spiritual development, and made noteworthy by his untiring labors and marked success.” Statistics bear this out. In 1840, there were forty-six clergy in South Carolina; by 1850, the number had increased to seventy-one. In the decade from 1840 to 1850, the number of parishes and congregations rose from thirty-seven to fifty-three, while communicants rose from 2,936 to 4,916. Of that number, it is remarkable that the number of black communicants increased from 973 in 1840 to 2,247 in 1850, or 150 percent. 209

Christopher Gadsden’s Assistants

Gadsden seems to have been particularly unfortunate in his assistants. The first was Thomas D. Frost, son of the former rector, who became Gadsden’s assistant in March 1815. He was forced to take leave from his post to go to Cuba for increasingly frequent lung hemorrhages in 1817 and again in 1818. He was so much improved after the last visit that he married Anne Grimke in June. She conceived a daughter, who was born before Thomas died suddenly while on another rest cure in Cuba. He was buried in the churchyard of Laguira, St. Mark Parish. Frederick Dalcho devoted two pages in eulogies to his personality, his youth, his modesty, his inexperience and so on. 210

The Reverend Allston Gibbs succeeded young Mr. Frost and served until he resigned in 1834 and went to Philadelphia. Forty years later, he “renounced” the ministry and was deposed by Gadsden, who had become bishop in the interim.

Succeeding Gibbs were two promising young men: the Reverend Daniel Cobia and the Reverend Abraham Kaufman. Both died young, leaving young widows.

Of Huguenot descent, Daniel Cobia was born in Charleston in September 1811. He was baptized at St. Michael’s Church by the Reverend Paul T. Gervais in the absence of its rector, William Dehon. After his mother’s death, young Cobia was raised by an affectionate aunt. His early classical education came from the Reverend Mr. Gilbert. He graduated from the College of Charleston at eighteen and graduated from General Seminary in New York in 1829 at age twenty-two. (This institution had been established in 1819 through the efforts of Bishops Dehon, Bowen and Gadsden and other churchmen of South Carolina.)

Cobia was ordained a deacon in St. Michael’s Church. He was called to St. Philip’s in 1834. Within a year, Cobia had become much loved by the church members and his family. Gadsden and Cobia sponsored a classical and religious school, although it was disbanded two years later. Cobia’s ministry was spent almost entirely in a temporary building in the west churchyard called the “Tabernacle,” which was erected after the fire destroyed the old church in 1835.

Cobia was suffering from the last stages of consumption when he married Louisa Hooper in 1835. Because of his delicate health, the Cobias did not have a large family wedding. They honeymooned for six months in St. Augustine, Florida, during a leave of absence from St. Philip’s. His son and namesake, Daniel Cobia, was born on All Saints’ Day 1836. Cobia did not survive his son’s birth by long. On February 8, 1837, he died of lung disease. Little Daniel Cobia died the following year. Cobia’s widow married the Reverend J.J. Roberts of North Carolina several years later. They had two children. 211

Young Cobia was noted for his gifted tongue. It was he who gave a moving sermon after the devastating fire of 1835. His memorial stone lies at the foot of the chancel steps in St. Philip’s Church. Today, communicants walk over the stone whenever they receive communion. 212

The Reverend Abraham Kaufman, who replaced Cobia, had an equally brief ministry. He, too, was well loved, and a similar stone in his memory was placed beside that of Cobia at the chancel steps. Kaufman was succeeded by the Reverend John Barnwell Campbell as assistant minister in 1840. Kaufman’s widow bore a son after his death. 213

The Beloved Bishop Gadsden Dies

In 1852, Bishop Gadsden announced that ill health would prevent him from continuing his ministry. After months of suffering, he died on June 24, 1852, in the sixty-sixth year of his life. He was buried under the chancel of St. Philip’s Church. Services were conducted by the Right Reverend Francis Huger Rutledge, bishop of Florida, whom Gadsden had consecrated only a few months earlier. Rutledge was assisted by the Reverend John Barnwell Campbell, who succeeded Bishop Gadsden as rector of St. Philip’s.

Christopher P. Gadsden, the bishop’s nephew, became the assistant minister of St. Philip’s that same year and remained at St. Philip’s until he was asked to become rector of St. Luke’s.

JOHN BARNWELL CAMPBELL

John Barnwell Campbell had been the assistant minister at St. Philip’s Church since 1840. When Bishop Gadsden died, he became the rector of the church.

Campbell was a native of Beaufort, where the Barnwell family was influential in reviving St. Helena’s Church. After the Revolution, religion in the Beaufort area was at a low ebb. Veterans of the Revolution were a hard-drinking, hard-living group of sociable men who were fond of dinners, barbecues and hunting clubs. Sunday was a day of boat racing, foot racing, drinking and fighting. Churchgoing was left to the women. St. Helena’s went without a priest from 1800 to 1804.

Campbell was born on August 1, 1784. He graduated from Queen’s College, Cambridge, and was consecrated a deacon by the bishop of Lincoln on June 12, 1808. He served as curate at Broughton-Ashley Parish in Leicester until he was invited to become the assistant at St. Helena’s Church. His return from England marks the beginning of steady growth of the church in Beaufort.

He became rector of St. Helena’s after being ordained a priest on July 9, 1811, by Bishop White of Pennsylvania. Within five years, St. Helena’s church building had become too small for the congregation and had to be lengthened by twenty feet; a gallery was added, and an organ was installed.

Catherine Amarinthia Percy married Campbell on November 21, 1811, four months after his ordination. She was the daughter of the Reverend William Percy and Catherine Elliott. (Catherine Percy was born in 1790 and died in 1818, leaving several children.)

In 1824, Campbell became the assistant to his father-in-law, then rector of St. Paul’s Radcliffeborough. (See chapter entitled “William Percy.”) Campbell became the rector of St. Philip’s in 1852 and resigned in 1858. He died in Newport, Rhode Island, and was later buried in St. Paul’s Churchyard. 214

Campbell’s successor at St. Philip’s was the Reverend William R. Dehon, the son of Bishop Theodore Dehon. His ministry is not covered in this work.

It was Colin Campbell, an uncle of John Barnwell Campbell, who presented the church with a clock and an accompanying chime of eight bells. The bells were later removed and given to the Confederate government to be recast as cannons.

The congregation continued to worship at St. Philip’s after the bombardment of Fort Sumter until it was hit by enemy fire on Thanksgiving Day 1863. Thereafter, it worshiped uptown at St. Paul’s. Bursting shells also drove the congregations of St. Michael’s and Grace Church away, and the combined congregations worshiped in St. Paul’s until Union forces entered the city. The Reverend W.B.W. Howe, then rector of St. Philip’s, was in charge.

When the Confederate troops evacuated in early 1865, Howe was banished from the city when he refused to pray for the president of the United States while the war against the Confederacy continued, following the example of the Reverend Robert Smith during the Revolutionary War. 215