AFTERWORD

The heartbreaking years of the War Between the States and Reconstruction are subjects for another book.

A Church Home was established after the war for destitute widows of Confederate war dead. Located just south of St. Philip’s, the building was purchased thanks to the unexpected generosity of John Wroughton Mitchell’s grandson, who made a substantial contribution on Easter Sunday. Across Church Street was a bar (owned by a member of City Council) whose rowdy patrons disrupted the tranquility of the residents and upset the vestry. The Church Home building now houses St. Philip’s administrative offices.

Let it suffice to say that at the end of hostilities, the church building was in deplorable condition. During the constant bombardment during the Siege of Charles Town, ten shells entered the walls, the chancel was destroyed, the roof was pierced in several places and the organ pipes were hauled away.

Steps were taken to repair the church sufficiently to allow the congregation to resume worship, but there was no money to properly restore the building. By 1877, a complete restoration was needed. 216 James Wellsman, a partner of former Confederate secretary of the treasury and wealthy businessman George Alfred Trenholm, contributed generously to the church during the Reconstruction period. He loaned St. Philip’s the money for the repairs and later gave the church an organ in spite of the financial reversals caused by federal taxes on his blockade-running activities.

On Tuesday, August 31, 1886, the vestry met to give reports showing that all debts incurred by the restoration of the war damage had been fully paid. 217 On that momentous evening, disaster struck. At 9:51 p.m., the first tremor of an earthquake (estimated to have been between 6.6 and 7.3 on the Richter scale) hit the southeastern United States, and within a few hours, the church building was nearly in ruins.

In Charleston, the initial shaking lasted just under a minute. The second shock lasted about thirty seconds and was less violent than the first, and the third was even less violent. A series of little shocks continued at fifteen- to twenty-minute intervals until after midnight. 218 The city was still recovering from the destruction of the war, and some buildings were still burned-out husks left from the fire of 1861. Debris was everywhere. The damage was enormous: some the cost was estimated to be between $5 million and $6 million; twenty-seven people were killed outright, with another forty-nine dying of injuries. 219

St. Philip’s Church was shaken to the core. Pieces of masonry arches and the cast-iron pilasters of the steeple lantern fell through the roof. There were cracks in chancel walls, and the galleries were dislocated. Even worse, the three porticos were separated from the structure. 220 The Sunday school building and church home on the corner were also damaged, forcing the ladies in the home to camp out in the churchyard for a time.

St. Philip’s vestry engaged New York architect William A. Potter as consulting architect for the repairs. His report to the vestry confirmed the suggestions of the local superintending architect W.B.W. Howe Jr., son of the Episcopal bishop. Following their recommendations, the vestry did not seek bids but instead hired a foreman to direct the day-by-day labor under Howe’s supervision.

William S. McGillivray was the first general foreman, but he was stricken with apoplexy and died. Architect Lewis R. Gibbes Jr. filled in on a 1 percent commission. Ten master builders applied for the position, and R.S.R. Crietzberg was selected; he was replaced in September 1887 by Albert Blaisdell, an architect from Augusta, Georgia.

The repairs were complex and sometimes dangerous. Three experienced riggers had to ascend the steeple to remove the remaining loose brickwork and iron pilasters. The steeple was held up by four sixteen-inch square timbers that extended down to the foundation, where they were anchored and mortised. According to Robert Stockton, who wrote the definitive work on the earthquake, “The weight of the steeple was divided equally among the four piers. Howe found that the northeast pier had settled 2½ inches and the southeast pier, 5 inches and that cracks had appeared in the Crowns of the arches…the brick arches were rebuilt as before but the Corinthian pilasters were replicated in Portland cement. The lantern was reinforced with iron rods 1½ in. in diameter and 19 inches long with wrought-iron straps.” 221

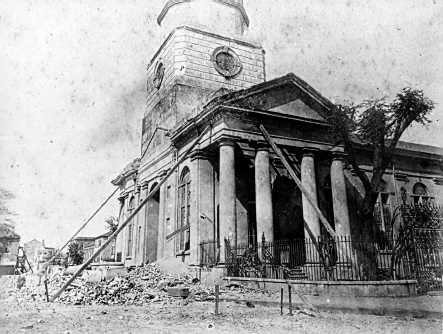

St. Philip’s after the earthquake. In the picture to the right, note the destruction in the steeple, and in the picture below, note the absence of the west portico and the wooden poles buttressing the remaining porticos. Photograph by Dr. E.P. Howland, a Washington, D.C. dentist. Courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina .

All three porticos were severely damaged. The west portico was rebuilt, replicating the original portico minus the entasis of the north and south porticos. The north and south porticos had to be reattached to the building and rebuilt, including the entire roof of the south portico.

In the body of the church, the northeast corner of the building was taken down nearly to the tops of the windows, and the gable end had to be rebuilt from the arch over the chancel to the apex. The extensive cracks under every window were cut out and filled with new brick and cement. Much of the interior wood framing had decayed and was replaced; the lath and plaster and much of the ornamental work had to be renewed.

The total cost of repairs to the church and Sunday school building was $18,915.54, excluding the organ repairs and architects’ fees. The materials included forty thousand bricks, 134 barrels of lime, 431 barrels of Rosendale cement, 150 barrels of Portland cement, 111 barrels of plaster of Paris and 6,500 pounds of iron. To finance the restorations, the vestry drew loans on the Glebe property that St. Philip’s shared with St. Michael’s, as well as received a $5,000 donation from Trinity Church, New York. Bishop Howe’s Earthquake Fund donated $4,121.50. 222

Since the earthquake, other “acts of God” have taken their toll on St. Philip’s Church. The authors hope that another parishioner will pick up the baton and carry on where we have left off.

Finis