BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF PARISHIONERS WHO MADE HISTORY

Sir Nathaniel Johnson’s Legacy

Thanks to Dr. Henry Woodward’s early explorations, English traders and explorers from Carolina established a substantial southern trading network that extended all the way to the Mississippi River. The French and Spanish were also vying for the vast, unsettled wilderness beyond the English colonies on the Atlantic seaboard. War broke out in 1702. In the British colonies, it was known as Queen Anne’s War. Although it was fought primarily between the British and the French in the northern colonies, it also affected Carolina because the French were allied with Spain.

Formal notification of hostilities arrived in Charles Town in 1702, and the Assembly voted to send an expedition to capture St. Augustine, then in control of the Spanish. Governor Moore led a force that was able to burn the town, but it did not take the fortified Castillo guarding the harbor before Spanish reinforcements forced the Carolinians to withdraw. The campaign did not eliminate the Spanish threat.

Such was the political climate when Sir Nathaniel Johnson replaced Governor Moore. The new governor had held the highest position of all those who had come to the province up to that point. From Keeplesworth, County Durham, he had been in the British army and had served as a Member of Parliament. As a loyal follower of the Stuarts, he was rewarded with knighthood and was appointed governor of the Leeward Islands in 1686. Two years later, he was removed from office for refusing to take oaths of allegiance to William and Mary after James II was deposed.

Col. William Rhett (1666–1722) , circa 1710, by Henrietta de Beaulieu Dering Johnston (American, circa 1674–1729), pastel on paper. © Image courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association, 1920.001.0001 .

No longer governor of the Leeward Islands, Johnson begged for permission to retire to Carolina, where he had purchased large grants of land. He arrived in 1689 with the title of cacique and took his seat as a member of the Council. Johnson introduced the silk culture to the colony and was considered one of the pioneers in that field. His country seat was a plantation fittingly called “Silk Hope.” He encouraged the local planters to cultivate rice and was quite popular because of his military experience. 223

When Johnson left the Leeward Islands, instead of accompanying her husband to Carolina, Anne Overton Johnson set out for England with her children. On the voyage, they were captured by a French privateer. Mrs. Johnson was imprisoned for almost a year before she died of the privations. Sir Nathaniel did not marry again, something unusual at that time. 224

In 1702, the Lords Proprietor commissioned Johnson as governor of both South and North Carolina, but his appointment was delayed because Johnson was suspected of being no friend to the “Glorious Revolution”; the Proprietors could not obtain Queen Anne’s approval until assurances were made that Johnson would observe all laws and obey instructions sent out by the Crown. Johnson’s commission arrived sometime in 1703. 225

With war on the horizon, Johnson anticipated trouble from the French and their Spanish allies. He strengthened the town’s bastions, built a fort on “Windmill Point” on James Island (now Fort Johnson), reorganized the militia and stationed a guard on Sullivan’s Island. In 1706, he outfitted a privateer to cruise the waters near Havana and ordered the captain to bring word of any hostile ships.

On August 24, the privateer rushed back to Charles Town with news that it was being chased by five French vessels carrying French and Spanish soldiers. (It seems that the captain of that armada had learned that Charles Town was suffering from a yellow fever epidemic. Assuming that the town was especially vulnerable, the captain collected a large force of men and headed for Carolina.)

The alarm was sent to Sir Nathaniel, who was at Silk Hope, some sixty miles away. In his absence, the commanding officer of the militia, Colonel William Rhett, summoned the citizens to arms. The governor and men from the outlying areas began arriving the following day. To avoid exposing the country troops to the epidemic, the militia encamped about half a mile beyond the city walls. Johnson’s presence greatly encouraged the people.

Before the militia was fully assembled, “five separate smokes” appeared on Sullivan’s Island, signaling the approaching fleet. The French ships sailed across the bar but turned back when they saw armed fortifications. They anchored off Sullivan’s Island. 226

The following morning, the French sent an emissary under a flag of truce. He was received by Captain Evans, commander of Granville Bastion. Blindfolded, he was led into the fort and asked to wait until the governor could receive him. The wily Sir Nathaniel tricked him into believing that the town was heavily fortified by having the emissary blindfolded again and taken from bastion to bastion to see assembled men at arms. The envoy did not realize that the armed men had been rushed through the alleys to appear again in the next bastion. 227 When the French emissary demanded that governor surrender the town and surrounding countryside, Johnson flatly refused.

“Half Moon Battery, Council Chamber and Governor’s House on right.” Detail from painting by B. Roberts, engraved by W.H. Toms, 1739. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

The governor’s ruse worked. The French thought that the city was well prepared for a frontal assault and sent marauding parties into the outlying areas instead. On James Island, friendly Indians had been organized and rushed screaming through the woods, causing the invaders to flee. A raiding party on Wando Neck was feasting on stolen cattle and pigs. These men had not posted a guard and were surprised by one hundred men. Many were killed or taken prisoner as they fled back to their boats. The enemy chose not to fight and sailed out to sea, and the governor sent out search parties to learn their whereabouts.

When word came that a French ship with two hundred armed men was moored in Sewee Bay, Rhett, who was also vice-admiral, sailed forth, while land forces under Captain Fenwick found and killed 14 and took 50 prisoners. Rhett surprised the ship in Sewee Bay. The Frenchmen never fired a shot. Their commander offered a ransom of ten thousand pieces of eight and quietly sailed away, leaving 230 prisoners behind. Their departure temporarily ended the Spanish threat.

The Proprietors rewarded the governor with accolades and a large tract of land. Historians have not recorded if they repaid the cost of the defense that Sir Nathaniel had borne himself. 228 The colonists were overjoyed that their honor had been restored after the failed campaign to St. Augustine. The Reverend Francis LeJau, newly arrived to the colony, described the town’s joy at its deliverance:

Upon my first Landing I saw the inhabitants rejoicing: they had kept the day before holy for a thanksgiving to Almighty God for having been safely delivered from an Invasion from the French and Spaniards who came with 5 vessels the 27th of August last, Landed in three places and having had 40 Men killed and left 230 Prisoners were forced back to Sea the 31st of the same month; We took one of their Ships and lost but one Man . 229

According to McCrady, “Sir Nathaniel Johnson, though a bigoted Tory, was a man of the highest character and a soldier of great reputation. His defense of the province upon the occasion of the Spanish and French invasion in 1706, forms one of the brilliant pages in South Carolina history.” 230

The Pirate Hunters

Early Charles Town was the southernmost British colonial port and a natural place for Caribbean privateers to congregate. They enjoyed the brothels and sold their ill-gotten treasure to some of the colony’s leading citizens. Anne Cormac (later Anne Bonny, the notorious female pirate) grew up in the area and met her pirate husband, James Bonny, in Charles Town.

Charles Town was also one of Edward Teach’s (Blackbeard) favorite stops. Teach commanded a captured French merchant vessel that he had armed with forty guns and renamed Queen Anne’s Revenge . He preyed on merchant ships in the West Indies and the eastern coast of the English colonies. Teach is said to have spurned the use of force, relying instead on his fearsome image to terrify his prisoners. Although he was fierce in battle, there is no account of his having murdered his captives. In 1718, he formed an alliance of pirates, including the infamous “gentleman pirate” Stede Bonnet, a Barbados plantation owner who had gone into “the trade” in 1717.

In 1718, Blackbeard blockaded the port of Charles Town with four ships and three hundred men. The pirates had already plundered four colonial merchant ships near the port before they boarded the England-bound Crowley . The ship’s eighty passengers were unceremoniously thrown into the hold, including the wealthy merchant Samuel Wragg and his four-year-old son, William.

Blackbeard, engraved by Benjamin Cole (1695–1766), from Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates: From Their First Rise and Settlement in the Island of Providence, to the Present Time. With the Remarkable Actions and Adventures of the Two Female Pyrates Mary Read and Anne Bonny. To Which Is Added. A Short Abstract of the Statute and Civil Law, in Relation to Pyracy (published 1724).

Wragg was a member of the Grand Council and tried to negotiate the release of the prisoners. He finally convinced Blackbeard that they could be exchanged for ransom. Blackbeard demanded medicine for his men, who were suffering not only from battle wounds but also from malaria and syphilis. Wragg volunteered to go ashore and offered to leave his four-year-old son behind as a guarantee that he would return. Blackbeard chose to send a less valuable hostage.

Days went by without the ransom, and Blackbeard grew tired of waiting. He sailed his flotilla into the harbor and threatened to have Wragg, his son and some other passengers killed if his demands were not met.

In the end, Governor Robert Johnson (Sir Nathaniel’s son) sent £300 to £400 worth of medicine to Queen Anne’s Revenge . The hapless prisoners were stripped of most of their clothing and put ashore in a remote spot. They were forced to walk through the woods to get back to town. Blackbeard is said to have plundered £6,000 in specie from Wragg alone. Once the pirates got the medicine, they reappeared and plundered more ships. 231

Blackbeard eventually parted company with Bonnet and headed north. He ran Queen Anne’s Revenge aground on a sandbar near Beaufort, North Carolina. 232 He settled in Bath Town and accepted a royal pardon, but he was soon back at the trade. When Virginia governor Alexander Spottswood learned of his whereabouts, he arranged for a party to attempt to capture the pirates. The group caught up with Blackbeard’s ship on November 22, 1718. During the ferocious battle that followed, Blackbeard and several of his crew were killed. Blackbeard was beheaded, and his head was suspended from the bowsprit of his victor’s sloop. The prize money for capturing Blackbeard was said to have been about £400.

In the summer of 1718, Stede Bonnet was pardoned by Governor Charles Eden of North Carolina and received clearance to privateer Spanish shipping. Not wanting to lose his pardon, he used the alias “Captain Thomas” and changed his ship’s name to Royal James . In August, his ship was anchored on an estuary of the Cape Fear River.

News reached Charles Town that pirates were rendezvousing at Cape Fear. Desiring to destroy the pirate threat once and for all, Governor Johnson commissioned William Rhett vice-admiral. Rhett pressed into service Henry and Sea Nymph , two ships then anchored in the harbor. At his own expense, he manned and armed them. Before they set sail, news came that the notorious pirate Charles Vane was plaguing the coast. Rhett immediately sailed off in hot pursuit. Not finding their prey, the ships proceeded to Cape Fear.

On the evening of September 26, 1718, the pirate hunters discovered three ships anchored in the inlet: Royal James and two prizes that Bonnet had taken. It was dusk, so Rhett’s ships anchored at the mouth of the river. The tide was going out, and the vessels soon became stranded on sandbars. Fearing a night attack from the pirates, the South Carolinians lay on their arms all night.

Early the next morning, the pirates set sail, hoping to blast their way past the ships. It was low tide, and as Royal James tried to avoid Rhett’s ships, it became stuck on a sandbar near its stranded adversaries. Too close for cannon fire, the crews traded small-arms fire for the next five hours. Henry ’s deck was slanted toward the pirates, while Royal James was stuck with its deck away from Henry , giving Bonnet and his men excellent cover to pick off their would-be captors.

Slowly the tide came in. The first boats to be freed were Henry and Sea Nymph . They set sail and advanced on Royal James . Rhett’s men outnumbered the pirates four to one. Surprisingly, instead of waiting to be boarded and possibly massacred, the pirates surrendered in spite of the fact that their captain wanted to fight to the death. Upon boarding Royal James , Rhett discovered that “Captain Thomas” was none other than the “gentleman pirate” Stede Bonnet.

The “Battle of the Sand Bars,” as it is called, cost ten men on the Henry , with fourteen wounded; Sea Nymph lost two men, with four wounded. Nine pirates were killed, and Rhett brought thirty-four pirates back to Charles Town for trial.

Stede Bonnet was not treated as a common pirate. He and one crew member were lodged in the home of the town marshal. Bonnet disguised himself in a dress and escaped with his crewman. Rhett volunteered to track him down in the overgrown sandhills of Sullivan’s Island, and Bonnet was captured after a fight and returned to Charles Town. 233

Right after Bonnet was apprehended, another pirate named Moody threatened Charles Town with a flotilla of three ships carrying fifty guns and two hundred men. The pirates were moored beyond the bar, where they preyed on outbound ships that could not see their sails from the wharves in town.

Governor Johnson called a meeting and informed the civic leaders that there would be no outside assistance. Naturally, Rhett was expected to take command, but he refused over some alleged affront with the governor. The governor then appointed himself admiral and outfitted four vessels manned by three hundred volunteers. The convoy crossed the bar with covered guns and tricked the pirates into thinking that they were merchantmen.

The Hanging of Major Stede Bonnet . Engraving published in Dutch version of Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates—Historie der engelsche zee-roovers…door Capiteyn Charles Johnson (1725), Amsterdam.

The governor suddenly hoisted the royal ensign, threw open the gun ports and broadsided the nearest ship, which quickly turned and headed for the open sea. Johnson followed and soon overtook the vessesl. After a desperate flight, the Carolinians boarded, only to find a hold full of female indentured servants and convicts bound for Virginia. The dead captain was the dreaded Richard Worley. After capturing the remaining pirate ships, the victors returned to town with their prizes in tow. The notorious Moody was nowhere to be found, and it was later learned that he had escaped to Jamaica and availed himself of “the King’s pardon.” 234

Anne Bonny . Engraving published in the Dutch version of Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates —Historie der engelsche zee-roovers…door Capiteyn Charles Johnson (1725), Amsterdam.

The sensational pirate trials in Charles Town were presided over by Chief Justice Nicholas Trott. Bonnet’s crew was tried and hung on November 8, 1718. The men were buried on the waterfront at White Point shoal, just above the high-water mark (near the corner of present-day Meeting and Water Streets). Two days later, Bonnet was brought to trial and charged with two acts of piracy. Judge Trott sentenced him to death. Bonnet wrote to Governor Johnson asking for clemency, but the governor endorsed the judge’s decision. Bonnet was hanged on December 10. Afterward, his body was thrown into Vanderhorst Creek (now Water Street). The killing of Blackbeard, Bonnet and their crews marked the end of the pirates’s stranglehold on Carolina shipping. 235

In the meantime, Anne Bonny had dumped her husband and had taken up with a couple of other pirates, one being the female pirate Mary Read. While in the Bahamas, Bonny began mingling with pirates in the local taverns. She met “Calico Jack” Rackham, captain of the pirate sloop Revenge , and became his mistress. Rackham and the two women recruited another crew and roamed the Caribbean until their capture. When the Jamaican forces overtook them, most of the men were hungover and cowered below deck, while the fearsome female duo of Bonny and Read attempted to subdue their would-be captors. The pirates were overcome and brought to trial. According to tradition, Bonny’s last words to Rackham were that she was “sorry to see him there, but if he had fought like a man, he need not have been hang’d like a Dog.” Both women claimed to be pregnant during the trial, a move that spared their lives. Read died in prison, presumably from childbirth. Bonny diappeared from history. Some say that Bonny’s father bribed officials to release her. Others claim that she took to the sea again. 236

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography notes that evidence provided by the descendants of Anne Bonny suggests that her father managed to secure her release from jail and bring her back to Charles Town, South Carolina, where she gave birth to Rackham’s second child. On December 21, 1721 she married a local man, Joseph Burleigh, and they had ten children. She died in South Carolina, a respectable woman, at the age of eighty on April 22, 1782. She was buried on April 24, 1782.

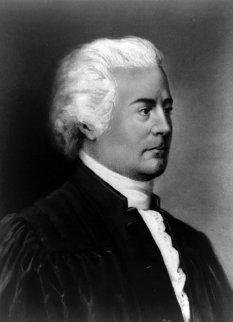

Chief Justice Nicholas Trott

Nicholas Trott was admitted to London’s prestigious Inner Temple in 1695 and was probably the first lawyer in the Carolina province. He became known to a wider audience when a transcroipt of the trails that he had written in 1719 was included in A General History of the Pyrates: From Their First Rise and Settlement in the Island of Providence, to the Present Time. With the Remarkable Actions and Adventures of the Two Female Pyrates Mary Read and Anne Bonny. To Which Is Added. A Short Abstract of the Statute and Civil Law, in Relation to Pyracy by a Captain Charles Johnson. (Johnson was believed to be a pseudonym, and the work is attributed to Daniel Defoe or to the publisher Nathaniel Mist or somebody working for him.)

Trott was from a prosperous family. He immigrated to Bermuda in 1696 to serve as attorney general. He received a commission as the first attorney general and naval officer in South Carolina, and records indicate that he was living in Charles Town by 1699. In 1703, he was appointed chief justice. He maintained a high profile during his years of public service. Among offices he held were commissioner and trustee of the Provincial Library at Charles Town and commissioner under the Church Acts (1704, 1706). He also served in the Fifth and Sixth Assemblies.

Trott ingratiated himself with the Lords Proprietor through his friendship with their secretary, Richard Shelton. After numerous trips abroad, Trott secured an appointment to the Grand Council and the right to veto any provincial law.

As leader of the Anglican party, Trott tried to exclude Dissenters from office. His arbitrary methods, exorbitant attorney’s fees and the disallowance of laws and acts the colonists favored caused great hostility in the province. Some thirty-one articles of complaint were filed against him in the Commons House. In 1715, the Commons House petitioned the Proprietors to remove his extraordinary powers, which they did in 1716. With this assurance, the Commons House passed a new election law that reduced Trott’s influence and kept him from ever regaining his former position of power. This marked the close of his public life. Trott’s abuse of power in the name of the Proprietors, along with that of his ally, William Rhett, was one of the causes of the “bloodless revolution” of 1719.

Trott went to England to agitate for a return to Proprietary rule, but he had destroyed his influence. He returned to South Carolina in 1722 and remained there until the end of his life. After his fall from power, he was involved in scholarly activities. In 1719, he wrote a lexicon of the Psalms entitled Clavis Linguae Sanctae and The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates , based on his participation as a commissioner in trying captured pirates in 1716. In 1721, he published The Laws of the British Plantations in America Relating to the Church, and the Clergy, Religion and Learning for the SPG. His final work, The Laws of the Province of South Carolina , chronicled the early legal and judicial history of Charles Town to the year 1719. He was also involved in the translation of the original Hebrew text of the New Testament and had completed a portion of it at the time of his death. In recognition of his academic work, he was awarded a Doctor of Civil Law degree from Oxford University in 1720 and a Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Aberdeen in 1736.

Trott’s first wife was Jane Willis of Bermuda, with whom he had one daughter, Mary (who later married William Rhett Jr.). Jane died in 1727, and the following year, he married Sarah Cooke, daughter of Edward Cooke of England and the widow of his political ally William Rhett. Through that marriage, he gained residency on the Hagen, his wife’s plantation on the Cooper River, which she had held in joint tenancy with her first husband. In 1729, the Trotts purchased seventy acres located near Ahagan Bluff and the Hagen. He also owned four lots in Georgetown. Nicholas Trott died on January 21, 1740, and was buried in St. Philip’s Churchyard two days later. His grave site is located under the street in front of the church. 237

The Wragg Family

Samuel Wragg, son of John Wragg of Chesterfield in Derbyshire, immigrated to Charles Town some time before March 1711. He arrived with considerable capital and went into partnership with his brother, Joseph. Wragg & Company became the town’s most successful slave traders, with a record of importing twenty cargoes of slaves in the years between 1735 and 1739.

Although much of his life was spent in London, Wragg obtained grants for 25 acres on Charles Town Neck, 6,000 acres in Craven County and 3,000 acres in Granville County. He acquired Ashley Barony (12,000 acres) in 1717 and kept 6,000 acres for his country residence. He and his brother jointly owned Dockon, a plantation of 1,680 acres in St. John Berkeley Parish.

Soon after his arrival, he was appointed road commissioner for Goose Creek Parish and held several offices, including that of tax assessor. His political career began in 1711 when he was elected to the Thirteenth Assembly for Berkeley and Craven, which he represented again in the Fifteenth Assembly. He represented St. Philip Parish in the Sixteenth Assembly and resigned when he was appointed to the Grand Council in 1717.

After his harrowing capture by Blackbeard, Wragg continued his journey to London and was appointed to the last Grand Council in June 1719. He remained in London and supported a limited paper currency in the colony. In 1727, he became the London agent for the colony’s Commons House. His first achievement was the appointment of a fellow moderate, Robert Johnson, as royal governor. They were able to obtain colonial appointments for their friends and relatives who replaced the extremists in the hard money faction. Wragg was successful in persuading Parliament to allow South Carolina merchants to ship rice directly to European ports, an extremely important concession.

Wragg married Marie DuBose. They had four children. He was known to be in Carolina by late November 1750 and died there on December 1. He was buried in St. Philip’s Churchyard. 238

William Wragg, the four-year-old who was captured by Blackbeard, was born in about 1714. Young Wragg was educated in England at the Westminster School, St. John’s College, Oxford and the Middle Temple. He was called to the English bar in 1733 and practiced law in England. He returned to South Carolina on or before his father’s death in 1750.

With his inheritance, young Wragg became one of the wealthiest men in the colony. He inherited 6,000 acres of Ashely Barony and a 1,026-acre tract on the Ashley River. He owned a house in Charles Town and acquired three working plantations and 6,900 unsettled acres on the Pee Dee River.

He was recommended by the Lords of Trade for the Council, where he was a loyal supporter of the Crown. This position was extremely controversial in the years before the Revolution, and Governor William Henry Lyttelton asked the Crown for his suspension, calling Wragg “an insolent and litigious spirit” in the Council. The Privy Council officially suspended him in 1757 despite the fact that he was the Crown’s most effective defender.

Undeterred, Wragg was elected to the Twenty-second Royal Assembly and continued in that body until 1768, serving again in the Thirty-third Royal Assembly. He was ever loyal to the Crown.

During the Stamp Act crisis, he was the lone vote against resolutions that supported the resolutions passed at the Stamp Act Congress. When the Stamp Act was repealed, he opposed the decision to erect a statue of William Pitt in Charles Town and tried to have it replaced with a statue of King George III. He refused an appointment of chief justice because he did not want his earlier support of the Crown to be construed as self-interest. He was appointed to Council but declined and retired to his plantation on the Ashley River.

In 1774, Wragg was declared “inimical to the liberties of the Colonies” and confined to Ashley Barony. In July 1777, he was banished from the colony for refusing to take an oath of allegiance to the rebel cause. Leaving his wife and daughters behind, he boarded the ship Commerce and set sail for Amsterdam. He was accompanied by his son, Billy, and a slave. On September 2, Commerce was within sight of Holland’s coast when a storm stuck. Wragg perished in an attempt to save his young son. At the time of his death, he owned 7,100 acres of land, 256 slaves and an estate worth £36,359. In 1779, his sister, who was living in England, had Wragg honored for his loyalty to the Crown by having a monument in his honor erected in Westminster Abbey.

Bucaneers , by Frederick Judd Waugh, graphically illustrating the horrors early settlers faced with the pirate scourge. Courtesy of the Library of Congress .

Wragg married twice. His first wife was Mary Wood, whom he married while living in England; they had two daughters—one married the speaker of South Carolina’s House of Assembly, John Matthews, in 1766, and Judith Wragg married an English soldier in the Prince of Wales Regiment in 1781. After the death of his first wife, Wragg married the daughter of his uncle, Joseph Wragg, in 1769; they had four children. 239

The Wragg name continues in Charleston through Wraggborough, which was founded after John Wragg, the eldest son of Joseph Wragg. He inherited seventy-nine acres between the Broad Path and the Cooper River. John Wragg died in 1796, leaving no children. In 1801, his siblings and their children had the land surveyed and laid into streets and then lots by Joseph Purcell. Some streets were named for Joseph Wragg’s children: Ann, Charlotte, Elizabeth, Henrietta, John, Judith and Mary. 240

Founding Mothers

In the early days of the colony, women had no political rights and, in essence, belonged first to their fathers and next to their husbands. Genteel women were chaperoned before marriage and never ventured forth without the protection of a father, a husband, a brother or other approved male escort. They were considered frail, helpless and unfit to do men’s work. In spite of the social restrictions, women of quality wielded a lot of power. With charm, beauty and creativity, they supervised the management of their households and enforced a code of conduct that affected the very fabric of Lowcountry culture. Two of St. Philip’s gentlewomen are especially noteworthy.

Eliza Lucas (1722–1793)

In the eighteenth century, the expanding English textile market relied on French indigo for blue dye. The Carolinians obtained an advantage over the exorbitantly priced French indigo when Parliament passed a bounty of 6d per pound for indigo grown in America and shipped directly to England. 241 The planters enjoyed what became known as the “indigo bonanza” and doubled their capital about every three to four years. Historian McCrady commented, “Indigo proved more really beneficial to Carolina than the mines of Mexico or Peru were to Spain.” 242 Amazingly, a teenage girl developed this cash crop. Her name was Eliza Lucas.

She was born on Antigua, where her father, George Lucas, was posted as a lieutenant colonel in the British army. Eliza and her two brothers were sent to a boarding school in London, and she returned to Antigua in 1737. Shortly thereafter, the Lucas family left for Carolina, where her father had inherited three working plantations. The family settled at Wappoo plantation and soon became part of the Ashley River social circle.

When in Charles Town, Eliza frequently visited Mrs. Elizabeth Lamb Pinckney, wife of Colonel Charles Pinckney. (He is not to be confused with a cousin, Governor Charles Pinckney, who later became known as “Constitution Charlie.”) She enjoyed many delightful conversations in the Pinckney household and borrowed many books from their extensive library.

During the upheavals caused by Queen Anne’s War, George Lucas was appointed lieutenant governor of Antigua and returned to the island in 1739. Due to his wife’s delicate health, he left his Carolina holdings under young Eliza’s supervision. She was sixteen. When the rice market collapsed, Governor Lucas sought to develop another viable crop and sent his daughter various types of seeds from Antigua. Although she experimented with ginger, cotton, alfalfa and cassava, her most successful venture was indigo.

A View of Charles Town the Capital of South Carolina in North America, Vue de Charles Town Capitale de la Carolina du Sud dans l’Amérique Septentrionale . Engraved by Pierre Charles Carnot, 1768. Courtesy of the Library of Congress .

Indigenous Carolina indigo yielded inferior dye and had not been able to compete with the French product. To maintain their lucrative monopoly, the French had outlawed the exportation of indigo seed. The industrious teenager spent three years growing the various seed strains that she received from her father. The third attempt succeeded.

Meanwhile, Eliza’s dear friend Mrs. Elizabeth Lamb Pinckney had become increasingly ill. She died in 1744, just a few months before Governor Lucas summoned his family back to Antigua. It did not take the widowed Charles Pinckney long to propose to Eliza. The sudden offer apparently did not cause any scandal, for Governor Glen gave the marriage license. The marriage was often cited as a perfect example of marital bliss.

Governor Lucas gave the couple the Wappoo indigo crop for a wedding present. The entire crop was saved for seed. The next year, Colonel Pinckney planted part of it at Ashepoo and gave the remainder to his friends. It was not long before the local planters were competing to produce the highest-quality dye. 243

By 1752, Colonel Pinckney had become the most prominent lawyer in the province. When the incumbent chief justice died unexpectedly, Governor Glen appointed Pinckney to fill the vacancy. Unfortunately, the appointment was not promptly confirmed by George II. This failure permitted the English ministers to appoint one of their cronies to the position. The Carolinians were indignant and appointed Pinckney to serve as liaison between the Provincial government and the Lords of Trade. Pinckney had inherited a small estate in Durham, England, and accepted the appointment in order to be in England while his sons, Charles Cotesworth and Thomas, completed their formal education.

The French and Indian War foreshadowed an interference with commerce and financial ruin for the Carolina planters. Pinckney’s official position as trade commissioner made him realize that it would be prudent to dispose of his colonial properties and reinvest in a more “secure” part of the world. The Pinckneys left their sons in school and set sail for America in March 1758. 244

Once back in the colony, Pinckney discovered that due to health reasons, his brother had been unable to supervise management of his lands. While inspecting his neglected plantations, Pinckney was stricken by malaria. He was taken to Jacob Motte’s house in Mount Pleasant, where he soon died. (More biographical information about Charles Pinckney can be found in Appendix E .)

Four Royal governors resided in the Pinckney mansion (James Glen, Thomas Boone, William Henry Lyttelton and Charles Grenville Montagu). This picture is of the remains after the fire of December 11, 1861. Courtesy of the College of Charleston Special Collections Library, Gene Waddell Collection, Charleston, South Carolina .

Eliza Pinckney never remarried and spent the rest of her life managing her husband’s plantations and investing the profits into her sons’ English education. She spent her last years at Hampton plantation with her daughter, Harriott Horry. Her last public appearance was in 1791, when President Washington visited South Carolina. She became ill in 1793 and, accompanied by her daughter, sailed to Philadelphia for treatment. Congress was in session, and she was visited by many of the new nation’s prominent citizens. She died the following month. President Washington requested to serve as a pallbearer, a particular honor as neither of her sons was able to attend the funeral. She was buried in St. Peter’s Churchyard, Philadelphia. For her contributions to South Carolina agriculture, Eliza Lucas Pinckney was inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame in 1989. 245

Rebecca Motte. From Women of the American Revolution by Elizabeth Ellet (1849) .

Rebecca Motte (1737–1815)

Like the Pinckneys, the Mottes supported the colonial side during the American Revolution. Rebecca Brewton Motte was the daughter of Robert Brewton, a prominent member of Charles Town society. She married Jacob Motte in 1758. The couple lived on Church Street and had three daughters. They enjoyed a comfortable, privileged life until the outbreak of the Revolution.

Mrs. Motte’s brother was Miles Brewton, a merchant who fervently supported the colonial cause. In 1775, he was elected to the second Provincial Congress and set sail for Philadelphia. Brewton was accompanied by his wife and three children, whom he planned to send to England. When their ship was lost at sea, Rebecca inherited his handsome brick home on lower King Street and Mount Joseph, a plantation near Orangeburg where the Congaree and Wateree Rivers merge to form the Santee. There she built a mansion similar to her brother’s home in Charles Town.

Jacob Motte spent much of his fortune providing for the colonial army. He died in 1780 a few months before Sir Henry Clinton took Charles Town. Clinton appropriated the Brewton mansion for his headquarters, as did Lord Rowden after him. Rebecca Motte was obliged to play “hostess” to the unwanted “guests” who took over her home. She prudently locked her three young daughters in the attic, far away from the British officers. They were guarded by a trusted servant, who smuggled food to them. Downstairs, Mrs. Motte entertained thirty British officers at her table daily.

Lord Rowden, whose reputation with the ladies was none the best, apparently knew of the duplicity, for upon his departure, he was said to have looked up at the ceiling and remarked that he regretted that he had not had the opportunity to meet the rest of her family. 246

Rowden permitted the Motte women to leave the city, and they retired to Mount Joseph. Due to its strategic location, the British had decided to establish a post there and make it the major convoy depot between Charles Town and the interior of the state. They evicted the Motte ladies and fortified the house. Named Fort Motte, the garrison was manned by British infantry under the command of Colonel Donald McPherson. The ladies moved into a small farmhouse on the hill opposite the new fort.

General Nathanael Greene had been sent to command the southern army, and he brought “Light-Horse Harry” Lee and his cavalry with him. After the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill near Camden in April 1781, Colonel Lee and General Francis Marion laid siege to Fort Motte. They arrived on May 8, and Lee set up headquarters at the farmhouse occupied by the Motte women. Marion commanded the ridge of the hill about four hundred yards from where the mansion stood. The combined forces of 600 men greatly outnumbered the 150 British troops defending Fort Motte.

On May 10, the Americans demanded that the British surrender the fort. McPherson refused. That evening, Marion and Lee learned that Lord Rowden had decided to withdraw his forces from Camden and was heading their way. Emboldened by beacon fires announcing Rowden’s approach, the next day the British again refused to leave the house.

Lee realized that the only way to secure the fort quickly was to burn the British out. He reluctantly informed Rebecca Motte of this necessity. She immediately produced a quiver of incendiary East Indian arrows that her brother had given to her years before.

By noon on May 12, the trenches dug by Marion’s men were close enough to enable sharpshooter Nathan Savage to fire flaming arrows onto the shingle roof. (According to another account, the roof was set alight by a ball of rosin and brimstone thrown by a sling.)

The British soldiers tried to extinguish the flames, but a six-pounder fired at them whenever they appeared. In a few moments, the white flag appeared, and Marion accepted the surrender. Afterward, both sides joined in putting out the fire. Once Mrs. Motte was restored to her lovely home, she invited both the American and British officers to dine at her table, where she is said to have received them all with equal courtesy.

After the war, Rebecca Motte returned to Charles Town and sold her King Street house to her son-in-law, Captain William Alston of the Waccamaw Company of Marion’s Brigade. 247 Against the advice of her friends, she purchased valuable swamp land on credit and moved to the country. Her determination built up a successful rice plantation that enabled her to pay off her husband’s debts in full. She died in 1815, leaving her children not only a valuable, unencumbered estate but also a rich heritage of patriotism and honorable deportment. 248

Christopher Gadsden

Born in 1724, Christopher Gadsden was the son of Thomas and Elizabeth Gadsden. Although family tradition states that Thomas Gadsden served in the Royal Navy, historians say that he was in the merchant service before becoming customs collector for the port of Charles Town. The elder Gadsden was ambitious, and during his lifetime, he amassed about six thousand acres of land, the most noteworthy being a sixty-three-acre tract fronting on the Cooper River just beyond Charles Town’s protective wall. Thomas Gadsden, his father, enjoyed socializing and was known for heavy drinking and high-stakes gambling. According to local lore, in 1725 the elder Gadsden lost the tract in a card game with Captain George Anson (later Lord Anson), commander of HMS Scarborough . 249

Young Christopher, called “Kittie” by his parents, was seven years old when his father sent him to live with his relatives and be educated in England. Afterward, he spent four years as an apprentice in the Philadelphia counting house of Thomas Lawrence, considered one of the best tutors in the colonies. After his father’s death in 1741, Christopher Gadsden inherited a sizable portion of his estate. When he attained his majority, he terminated his mercantile training and planned to go into business for himself.

Gadsden returned to England to visit his relatives and took passage home on HMS Aldoborough . When the purser died, the captain appointed Gadsden in his place. Gadsden continued as purser while the ship was stationed in Carolina.

In 1746, Gadsden married Jane Godfrey, a young lady with a sizable fortune. Shortly after his marriage, Gadsden sailed from Charles Town when Aldobrough went north to participate in the British siege of the French fortress in Louisburg, Nova Scotia. When Aldobrough returned to Carolina two years later, Gadsden left the ship and established himself as a merchant. 250

Starting with a store on Broad Street, he expanded his business activities to the Prince George Winyah (Georgetown) area and made a fortune trading with the frontier. By 1761, he had closed his stores at Cheraws and Georgetown and began developing the village of Middlesex (also known as Gadsden’s Green and Federal Green), bounded by present-day Calhoun, Anson and Laurens Streets and the Cooper River.

Gadsden had the marsh filled, straightened the creek between his land and Alexander Mazyck’s and dug across present-day Calhoun Street. The block of Calhoun between Washington Street and East Bay was intended to be a marketplace. He laid out six wharf lots and 197 building lots 251 and proceeded to construct a one-thousand-foot wharf described as a “stupendous work…which is reckoned as the most extensive of its kind ever undertaken by any one man in America.” 252 In addition to land development in Charles Town, he acquired a working plantation on the Pee Dee River and another on the Black River; ninety slaves worked his plantations.

Gadsden was one of the founders of the Charles Town Artillery Company and took part in the Cherokee expedition in 1761. However, his fits of temper rendered him unsuitable for military life, and he returned to the private sector. He became deeply involved in city life and built a house on Front Street staffed by twenty-four slaves. He was a vestryman at St. Philip’s and a member of the religious and literary society, organized by its rector, Richard Clarke. He was a member of the South Carolina Society and the Charles Town Library Society.

Politically, he served in the Assembly for almost three decades and represented St. Philip Parish for most of them. He became the leading spokesman for the “mechanics,” a small middle class of talented, prosperous artisans comprising about 20 percent of Charles Town’s population. The mechanics met under a live oak tree in Mazyck’s pasture on Charleston Neck (currently Alexander Street).

Gadsden’s writings, as printed in Peter Timothy’s Gazette , seemed to express the artisans’ sentiments, and lacking the influence to be elected to the Assembly, they adopted Gadsden as their spokesman. Always feisty, Gadsden defied the British government whenever possible. The Assembly finally denied his seat on a minor infraction. This caused him to oppose the British even more vehemently.

In 1763, England’s Prime Minister George Grenville set about offsetting the massive national debt incurred by the Seven Years’ War (known in America as the French and Indian War). The American Duties Act of 1764 placed a 3d tax on imported molasses (used in the manufacture of rum by New England distillers). That same year, Parliament passed the Currency Act, which prohibited the colonies from printing paper money. This act forced colonials to buy from British merchants on credit. The financial crisis after the war forced English merchants to call in their debts, causing great hardships and bankruptcies for colonial importers.

Christopher Gadsden, before 1860, attributed to Rembrandt Peale (American, 1778–1860), oil on canvas. © Image courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association, 1997.003.0001 .

The last straw was the Stamp Act of 1765. This legislation required that all legal documents, newspapers and playing cards have a stamp affixed to them or that they be printed on stamped paper. Colonials viewed the act as a violation of the right of Englishmen to be taxed only with their consent . The rallying cry became “taxation without representation.” By the end of 1765, all colonial assemblies except Georgia and North Carolina had sent formal protests to England.

When the Stamp Act protests turned violent, friends and members of St. Philip’s congregation followed Gadsden’s lead. South Carolinians hauled down the British flag and hoisted one of their own. In October 1765, the colonies convened the Stamp Act Congress in New York. Christopher Gadsden was a key player.

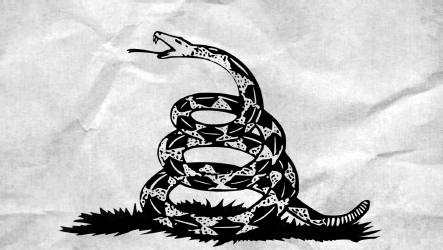

Christopher Gadsden designed the distinctive yellow flag with a coiled rattlesnake poised over the words “Don’t Tread on Me.”

When the Stamp Act was repealed, twenty-six men gathered in Mazyck’s pasture to celebrate the occasion. Gadsden warned the assembly that they should be prepared for a struggle to “break the fetters whenever again imposed on them.” Afterward, the men joined hands around the oak tree and called themselves “defenders and supporters of American Liberty.” The place was thereafter known as the “Liberty Tree.” (In August 1776, thousands gathered at the Liberty Tree to hear Major Barnard Elliott read the Declaration of Independence. When Charles Town surrendered in May 1780, General Clinton ordered the tree to be chopped down.)

Gadsden is remembered for his five-month newspaper debate with William Henry Drayton, whose unpopular importation views caused him to become persona non grata to the non-importation faction. They ostracized Drayton socially and boycotted him at the docks, forcing him to market his own rice in London at a great disadvantage. Drayton later went to London and was able to secure an appointment to the colonial Royal Council. No one knows why the great polemicist had a radical political transformation, but once back in the colony, he soon abandoned his impassioned support of the Crown and began to rail against British authority to such an extent that he was suspended from the Royal Council in 1774. Once Drayton changed his tune, he and Gadsden became fast friends.

Gadsden served in the Continental army, rising to the rank of brigadier general. When he was not promoted to commander of the South Carolina troops, he had a nasty newspaper exchange with General Robert Howe, the man who had received the appointment. The feud became so heated that Howe finally challenged Gadsden to a duel. When they met, Gadsden insisted that Howe shoot first. Howe fired and grazed Gadsden’s ear. Gadsden took his time before he dramatically raised his weapon. Much to everyone’s relief, he very deliberately fired into some nearby trees. Honor satisfied, the two generals shook hands and departed.

After the British captured Charles Town, Gadsden was among twenty-nine exiles sent to St. Augustine in August 1780. When they arrived, Governor Tonyn offered them freedom of the town if they would give their parole. Most accepted, but Gadsden refused, claiming that the British had already violated one parole—he could not give his word to a false system. He was imprisoned in the Castillo de San Marcos for ten months before being released and sent to Philadelphia. When Gadsden learned of Cornwallis’s withdrawal to Yorktown, he returned home to help with the restoration of South Carolina’s civil government.

Gadsden was active in civic affairs after the war ended. He was elected governor but declined the office because of his age and health. He did serve one last term in the General Assembly. By then, he had lost some of his Revolutionary fervor and favored leniency for the Loyalists, an unpopular stand at the time. He was a member of the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution. In 1800, he came out of retirement to serve as a John Adams elector.

Gadsden married three times. By Jane Godfrey, he had two children. His second wife was Mary Hasell, daughter of the Reverend Thomas Hasell; they had four children. In 1775, he married Ann Wragg, the daughter of Joseph Wragg. There was no issue from this marriage.

The grand old statesman died from an accidental fall in August 1805. At his request, he was buried in an unmarked grave in a plain coffin at St. Philip’s Churchyard. The grave site is next to that of his parents. 253

Parish Founding Fathers

Most of South Carolina’s “Founding Founders” were members of St. Philip’s and St. Michael Parishes. The fourth South Carolina signer of the Declaration of Independence was Thomas Lynch Jr., from Prince George Winyah (now Georgetown). The fourth South Carolina signer of the U.S. Constitution was Pierce Butler, who was the first South Carolinian elected to the U.S. Senate.

Henry Laurens: President of the Continental Congress (1777–1778)

History remembers Henry Laurens as the Patriot who was imprisoned in the Tower of London and later exchanged for Lord Cornwallis, the British earl who surrendered to George Washington at Yorktown. In South Carolina, Laurens is noted for being one of the most successful merchants in the American colonies.

Born in Charles Town in 1724, Henry Laurens was the son of John Laurens and Esther Grasset. Laurens’s father was a prosperous sadler who saw to it that his son was well educated in the colony before he sent him to England to clerk for a London merchant. After his father’s death, Laurens made valuable contacts with merchants in English ports. When he returned to Carolina, he formed a partnership with George Austin and established Austin & Laurens, a firm that brought Laurens a fortune through trading in slaves and rice.

Henry Laurens, painted while in the Tower of London by artist Lemuel Francis Abbott. Courtesy of the Library of Congress .

In 1755, Laurens purchased a tract of land north of the old city where he build a “large, elegant brick house of sixty feet by thirty-eight,” with piazzas on the south and east sides overlooking the marshes and the Cooper River. Adjoining the house was a four-acre botanical garden maintained by an English gardener. As was the custom of the town’s wealthy, it boasted citrus trees and exotics such as capers, ginger and guinea grass. 254

Active in the community, Laurens was a vestryman and churchwarden at St. Philip’s and was a member of the religious club formed by its rector, Richard Clarke. He was also a member of the Charles Town Library Society. He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in a Provincial regiment. A Mason, he was treasurer of Solomon’s Lodge and provincial grand steward in 1754.

Beyond Charles Town, Laurens’s holdings included eleven thousand acres of land at New Hope plantation, Broughton Island plantation, Wright’s Savanna plantation and Mount Ticitus; six thousand acres of undeveloped tracts at Long Canes; and unsettled tracts totaling four thousand acres in Georgia. His country seat was Mepkin, a 3,143-acre plantation on the Cooper River. He and his wife, Eleanor Ball Laurens, had twelve children, of whom four survived childhood. (His promising son, Colonel John Laurens, was killed in the Revolution.)

In politics, Laurens represented St. Philip Parish in the Royal Assembly from 1757 to 1760 and again from 1768 to 1772. He represented the parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael in the First and Second Provincial Congress, serving as president in the First Provincial Congress in 1775. He represented St. Philip and St. Michael in the First, Second, Third and Fourth General Assemblies (1775–85).

Laurens was elected to the Continental Congress in 1777 and took his seat in Philadelphia in June of that year. He was elected president in November. During his presidency, the colonials secured an alliance with France and signed the Articles of Confederation.

In 1779, Laurens was named a commissioner to negotiate a treaty with the Netherlands. He was captured at sea en route to the Netherlands. He was briefly imprisoned for high treason in the Tower of London and was released when his English friends posted a bond of £10,000 sterling. Laurens was later exchanged for Lord Cornwallis, the British general who surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia. (The surrender and the capture of both Cornwallis and his army of 7,200 men prompted the British government to negotiate an end to the conflict.) Laurens then joined the American commissioners negotiating a peace treaty in Paris.

In 1784, Laurens returned to America and returned to South Carolina the following year. His last foray into politics was when he represented St. John Berkeley Parish at the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1788. He died at Mepkin in 1792 and was cremated, as stipulated in his will. 255

John Rutledge: Thirty-first Governor of South Carolina and Signer of the U.S. Constitution

John Rutledge was one of South Carolina’s most accomplished statesmen. He was the first governor of South Carolina following the signing of the Constitution and the thirty-first governor overall. He was a modest man and eschewed the titles of many of the positions he held.

John Rutledge (1739–1800). Courtesy of the Library of Congress .

Rutledge was born in 1739, the oldest son of Dr. John Rutledge and Sarah Hext. He studied law in the colony and in 1754 was among the privileged South Carolinians admitted to the Middle Temple, one of the four Inns of Court in London. Rutledge was called to the English bar in 1760 and to the South Carolina bar the following year. In 1763, he married Elizabeth Grimké, daughter of Frederick and Martha Emmes Grimké.

In 1761, he entered politics and served in the Royal Assembly from 1761 to 1775, while holding numerous public offices during the same period. In 1765, he served as a delegate to the Stamp Act Congress in New York, where he advocated a moderate policy that would avoid severing ties with the mother country. He was a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses (1774–76). In 1776, he was elected president of the state’s First General Assembly. He was then elected president of the new government and given broad dictatorial powers in March 1776. He represented the parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael in the Second and Third General Assemblies in 1778 and 1779. In spite of his reservations about separating from Great Britain, he was chosen governor of South Carolina in 1779.

During the Revolution, Rutledge worked for the southern Continental army and served as president of South Carolina. An interesting Revolutionary War anecdote relates that when Richard Furman, the charismatic Baptist preacher, volunteered to fight, Rutledge persuaded him to convert Loyalists to the Patriot cause in the western part of the state. Furman was so successful in this mission that Lord Cornwallis was said to have feared his fiery prayers “more than the armies of Marion and Sumter.” 256

When Charles Town was besieged by the British in 1780, the legislature granted Rutledge war powers “to do anything necessary for the public good, except the taking away of a citizen without legal trial.” During the British occupation of Charles Town, Rutledge’s property was seized. He escaped to North Carolina and attempted to rally forces to recapture the city. Rutledge tried to unify the state by granting pardons to many Loyalists on the condition that they report for six months’ militia duty within thirty days.

With the end of the Revolution approaching in 1782, Rutledge resigned the governorship and became a member of the Fourth General Assembly, which elected him to the Continental Congress. In 1787, he was elected a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and was among the South Carolinians who ratified that document.

Rutledge was appointed an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court by President George Washington in 1789. He resigned to become chief justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court in 1791 and served in that capacity until Washington commissioned him chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court as a “recess appointment” on July 1, 1795. In December 1795, the U.S. Senate failed to confirm the “recess appointment,” and Rutledge resigned as chief justice on December 28, 1795. This political defeat was supposed to have affected him deeply. During his “recess appointment” as chief justice, Rutledge authored several important decisions. He is considered the second chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (after Chief Justice John Jay resigned to become governor of New York), and his bust is located in the Supreme Court building in Washington.

Toward the end of his life, Rutledge was in debt and threatened with the loss of his entire fortune. Stricken with gout and overwhelmed by the enormity of his debt and his wife’s death in 1792, he spiraled into a deep depression. He is known to have attempted suicide by jumping off Gibbes’s bridge into the Ashley River, a “disgrace” that his relatives kept as quiet as possible. The venerable statesman died on July 18, 1800. He was buried in St. Michael’s Churchyard. 257 (It should be noted that at that time, St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s were legally incorporated.)

Years later, Alexis de Tocqueville came to study the infant government of the United States. When he tried to discover the framer of the U.S. Constitution, nobody knew for sure who he was. De Tocqueville studied the documents and concluded that John Rutledge was the only possible candidate. He was shocked to discover that in 1830, even his descendents in Charleston were indifferent to Rutledge’s contributions to history. Time had gone on, and another generation was looking for ways to destroy the very union the Founding Fathers had so painstakingly crafted. 258

Thomas Pinckney: Thirty-sixth Governor of South Carolina

The Pinckney brothers, Thomas and Charles Cotesworth, were the sons of colonial chief justice Charles Pinckney and Eliza Lucas Pinckney. Both were formally educated at the prestigious Westminster School and remained in England after the rest of the family returned to South Carolina in 1758.

Thomas Pinckney, the younger son, was born in 1750. After graduating from Christ Church, Oxford, he attended the French Military College in Caen, France, for one year before studying law at the Inner Temple in London. He returned to Carolina in 1774 and commenced the practice of law.

Thomas was an ardent supporter of the colonial cause. He was commissioned a captain of engineers in the First Regiment, Continental army, in 1775 and was promoted to major in the disastrous Florida Campaign, during which only half of the soldiers survived to return home. He served under General Benjamin Lincoln in 1778–79 and with Count d’Estaing in 1779 in the defense of Charles Town; afterward, he became an aide-de-camp to General Horatio Gates. He was wounded at the Battle of Camden and was captured by the British. After his parole, he served under the Marquis de Lafayette in Virginia.

Thomas was elected the thirty-sixth governor of South Carolina in 1787 and presided over the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1788. He served in the South Carolina House of Representatives until George Washington appointed him United States minister to Great Britain from 1792 to 1796. He was envoy extraordinary to Spain from November 1794 to November 1795 and negotiated the treaty settling the boundary between the United States and East and West Florida, as well as the boundary between the United States and Louisiana, thus giving the United States freedom of navigation on the Mississippi River.

Thomas ran as the Federalist candidate in the election of 1796 and came in third behind John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. He was elected as a Federalist to the Fifth Congress to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of William L. Smith and was reelected to the Sixth Congress, serving from 1797 to 1801. After that term, he returned to South Carolina. During the War of 1812, he was appointed major general and served throughout the war. He was president general of the Society of the Cincinnati from 1825 to 1828.

Thomas Pinckney. Courtesy of Thomas Pinckney Lowndes .

Thomas was married twice, first to Elizabeth Motte and then to her sister, Frances, the widow of John Middleton, a cousin of Arthur Middleton, signer of the Declaration of Independence. Elizabeth and Frances were two of Rebecca Brewton Motte’s three daughters who hid out in the attic when the British made the Miles Brewton mansion their headquarters during the occupation of Charles Town.

Thomas Pinckney died in Charleston on November 2, 1828, and is buried in St. Philip’s Churchyard. 259

Charles Pinckney: Thirty-seventh Governor of South Carolina and Signer of the U.S. Constitution

Better known as “Constitution Charlie,” Charles Pinckney was born in 1732, the son of Ruth Brewton Pinckney and William Pinckney. He was privately educated under the direction of a noted South Carolina scholar and author, Dr. David Oliphant. His tutor instilled in Pinckney a political philosophy that viewed government as a solemn social contract between the people and their sovereign; if government failed to fulfill the contract, the people had a right to form a new government. When Pinckney left Oliphant’s care, he completed his formal education by studying law under his father’s personal direction. He was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1752 while still in his twenty-first year. At the age of thirty, he received an honorary degree from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). A scholar, Pinckney mastered five languages and accumulated a personal library of more than two thousand volumes.

Part of the Lowcountry aristocracy, Pinckney owned five plantations (worked by 389 slaves) and a home on Queen Street in Charles Town. He was a vestryman of St. Philip and St. Michael Parishes. He was a member of the South Carolina Society, a provincial grand steward of the Masons, a member of the Charleston Library Society and a member of the St. Andrew’s Society.

At age twenty-two, he began his public career in the Twenty-first Royal Assembly and continued in every subsequent assembly until 1775. Other offices included commissioner to regulate trade with the Creek Indians, justice of the peace for Berkeley and Colleton Counties and commissioner to build an Exchange and Customs House and a new Watch House in Charles Town.

Pinckney supported actions against the British government, and in 1770, he presided over a meeting at the famous Patriot meeting place, the Liberty Tree. During the war years, he was a member of the First and Second Councils of Safety. He was a member of the Privy Council in 1779 and fled Charles Town with Governor John Rutledge in April 1780. Pinckney returned voluntarily the following June and gave parole. Because of his position, he came under intense pressure from the British to renounce the Patriot cause. When the young officer resisted, his captors revoked his parole and incarcerated him.

Charles Pinckney. Attributed to Gilbert Stuart. Courtesy of the National Park Service .

After the war, Pinckney retired from active service and resumed his duties in the South Carolina legislature. In 1784, he represented South Carolina in the Continental Congress, a post he held for three successive terms. In 1786, he was among those calling for a strong federal authority to raise revenues, and in 1787, he led the fight for the appointment of a “general committee” to amend the Articles of Confederation, a move that led directly to the Constitutional Convention.

Chosen to represent South Carolina at the Convention, Pinckney arrived in Philadelphia with many proposals in hand. He stood out as one of the most active members of the Convention. More than thirty provisions can be traced directly to his pen. Among the issues for which he fought was the subordination of the military to civil authority, as outlined in the provision that declared the president commander in chief and retained for Congress the power to declare war and maintain military forces. Pinckney also tried unsuccessfully to include some explicit guarantees concerning trial by jury and freedom of the press, measures that would later be enshrined in the Bill of Rights.

Pinckney returned home to serve in the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1788. He also chaired the assembly that drafted a new South Carolina constitution. In between, he won the first of several terms as governor.

His nationalist sentiments were compatible with those espoused by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. He served as the state manager of Jefferson’s successful campaign for president in 1800 and supported Jefferson’s program in the United States Senate. Pinckney resigned in 1801 to become ambassador to Spain, where he helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase.

Pinckney returned home once again in 1804 to resume an active political career in the state legislature and served a fourth term as governor. While in office, he supported an amendment to the state constitution to increase representation from the frontier regions and pressed for measures that would eventually lead to universal white male suffrage.

He retired from politics in 1814 to attend to his personal finances, which had eroded through years of absence. In 1818, Pinckney responded to the pleas of his political allies and ran for office one last time, winning a seat in the House of Representatives.

Charles Pinckney married his first cousin, Frances Brewton; they had eight children. He died in St. Andrew Parish in 1824 and was buried in the parish churchyard. He was later reinterred in St. Philip’s east churchyard near the church building. A historical marker is located near the gate. 260

Edward Rutledge: Thirty-ninth Governor of South Carolina and Signer of the Declaration of Independence

Edward Rutledge was one of signers of the Declaration of Independence and the thirty-ninth governor of South Carolina. He was born in 1749, the youngest son of Dr. John Rutledge and Sarah Hext Rutledge. He read law under his older brother, John, and in 1767 continued his education at the Middle Temple in England. He was called to the English bar in 1772. He returned to Charles Town and was admitted to the bar the following year.

In 1774, he married Henrietta Middleton, daughter of Henry Middleton and Mary Williams Middleton, and by that marriage allied himself to one of the wealthiest and most political families in the province. They had three children before she died in 1792. Later that same year, he married Mary Shubrick, daughter of Thomas Shubrick and Sarah Motte Shubrick.

Rutledge owned a plantation in Winton County, property in Columbia, a townhouse in Charles Town and more than fifty slaves. He had a successful law practice with his partner, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

Along with his brother, John, Rutledge represented South Carolina in the Continental Congress in July 1774. In early July 1776, he was instructed to vote in favor of the Declaration of Independence. He was then twenty-six, making him the youngest of the signers.

Edward Rutledge, oil, 1873, by Philip F. Wharton, after James Earl (Earle). Courtesy of the Independence National Historical Park . From the Collection of the Old Exchange Building, Charleston, South Carolina.

He returned home in November 1776 and represented St. Philip and St. Michael in the General Assembly. He was elected to the Continental Congress in 1779 but did not attend because of illness.

During the Revolutionary War, Rutledge served as a captain of artillery in a company that defeated the British at Beaufort in 1779 and as a lieutenant colonel of the Charleston Battalion of Artillery in 1780. He was captured by the British after the fall of Charles Town and sent to St. Augustine, where he remained a prisoner of war for eleven months before his exchange.

After his release, Rutledge returned to the state assembly, where he served continuously until 1796. He drew up the bill that advocated the confiscation of Loyalist property and, along with his partner, C.C. Pinckney, later purchased two confiscated Tory estates on the western bank of the Cooper River: Tippicutlaw and Charleywood.

Like his peers, Rutledge was a member of the South Carolina Society and was admitted to the prestigious Charleston Library Society in 1783. He was also a member of the Artillery Society and the St. Celia Society. He held numerous local offices, including road commissioner and commissioner of the streets. He was director of the Charleston branch of the Bank of the United States, trustee of the College of Charleston and director of the Inland Navigation Company. He was a vestryman of St. Michael’s Church.

Rutledge was a presidential elector in 1788, 1792 and 1796. He represented St. Philip’s and St. Michael in 1788 at the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution; in 1790, he was a member of the convention that passed the state constitution. The following year, he authored a bill that abolished primogeniture in the state.

In 1794, George Washington offered him the position of associate justice on the United States Supreme Court, but Rutledge declined. He served in the South Carolina Senate for two years and was elected governor of the state in 1798. He was still serving in that capacity when he died of apoplexy in January 1800. According to tradition, the stroke was brought on by news of George Washington’s death. Governor Rutledge was buried in St. Philip’s Churchyard. 261

Thomas Heyward Jr.: Signer of the Declaration of Independence

Born in 1746 at Old House plantation in St. Helena Parish, Thomas Heyward Jr. was the son of Daniel Heyward and Maria Miles Heyward. He studied law at the Middle Temple and was admitted to the English bar in 1770. He returned to Charles Town and was admitted to the bar in 1771. Heyward divided his time between his law practice and a plantation in St. Helena Parish and represented St. Helena in the last four Royal Assemblies.

St. Philip and St. Michael elected him to the First Provincial Congress and returned him to the Second Provincial Congress (which resolved itself into the First General Assembly in 1776).

Thomas Heyward Jr., oil, by Marguerite Miller, after copy of Stolle’s copy of Jeremiah Theus. Courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina .

Heyward was elected to the Continental Congress upon Christopher Gadsden’s resignation. On July 4, 1776, he was one of four South Carolinians who signed the Declaration of Independence. When Heyward returned home, his father was reported to have expressed his indignation:

“A bold and precipitate measure I think. Undisciplined militia like ours cannot stand against the trained armies of the king. We shall surely be beaten.”

“No doubt,” was the reply .

“What shall we do then?”

“Raise another army and keep up the struggle.”

“What, to be beaten again?”

“Certainly, and the same may follow over and over again; but we shall become reconciled to the evils of war and acquiring military experience, shall ultimately gain the victory.” 262

Heyward continued to serve in General Assembly until Charles Town fell in 1780.

During the Revolution, he was a captain in the Charles Town Artillery Company and was wounded at the Battle of Beaufort in 1779. He was captured after the fall of Charles Town and was among those exiled to St. Augustine. 263

Heyward’s brother-in-law, John Mathewes, worked with the Continental Congress to pass a bill authorizing an exchange of prisoners. Mathewes personally petitioned George Washington to assist the southern leaders sent to St. Augustine. Washington wrote to him that a solution was difficult because the British prisoners were of inferior rank. It was some months before those held in St. Augustine were exchanged and taken to Philadelphia.

Heyward returned to South Carolina after the British evacuated. He was elected to the Fourth General Assembly and represented St. Philip and St. Michael from 1782 to 1790. As a judge of the Court of General Sessions and Common Pleas (1779–89), he helped establish educational standards for the South Carolina bar. He was a member of the Charleston Library Society, a vestryman of St. Michael’s Church, a warden of Charleston’s Sixth Ward and a trustee of the College of Charleston. He also served on several commissions. He was a member of the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1788 and a member of the state Constitutional Convention in 1790. Heyward was a founder and first president of the Agricultural Society of South Carolina.

Thomas Heyward’s first wife was Elizabeth Mathewes, daughter of John Mathewes and Sarah Gibbes Matthewes. They had five children, but only son Daniel survived childhood. Elizabeth met her husband in Philadelphia after his release from St. Augustine. She was honored by General Washington, who selected her as the “Queen of Love and Beauty” at a ball given in honor of the birth of the dauphin of France. Elizabeth died in Philadelphia in 1782. Heyward married Elizabeth Savage in 1786; they had three children. He spent most of his time on his plantation and rented his Church Street town house to the city so that George Washington could stay there when he visited Charleston in May 1791. Thomas Heyward died in 1809 and was buried in the family cemetery on Old House plantation in St. Luke Parish. 264

Arthur Middleton: Signer of the Declaration of Independence

Arthur Middleton was born at Middleton Place on the Ashley River in 1742. He was educated in England at Westminster School, St. John’s College, Cambridge and the Middle Temple. He returned to South Carolina in 1763 and was elected to the Twenty-seventh and Thirty-first Royal Assemblies.

In 1764, he married Mary Izard, daughter of Walter Izard Jr. and Elizabeth Gibbes Izard. In 1768, he took his family on an extended European tour during which he studied fine arts and literature. They returned to Carolina in 1771.

Middleton was elected by St. Philip and St. Michael to the First and Second Provincial Congresses. While a member of the Second Provincial Congress, he helped draft the state’s first constitution and designed the reverse of the state seal. He was an early advocate of a total break with Great Britain and frequently clashed with the more conservative Rawlins Lowndes.

Arthur Middleton , oil, 1771, from a portrait by Benjamin West. Courtesy of Middleton Place Foundation, Charleston, South Carolina .

In February 1776, the Provincial Congress elected Middleton to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where he signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4.

Middleton represented St. Philip and St. Michael in the First, Second and Third General Assemblies. Among offices he held were justice of the peace for Berkeley County and commissioner (in cutting a canal from Broad Street to the Ashley River). He was a member of the Charleston Library Society and a trustee of the College of Charleston.

When Charles Town fell, Middleton was taken prisoner by the British and exiled to St. Augustine. He was exchanged in 1781. He suffered heavy losses during the Revolution, including the theft of two hundred slaves. His wealth was such that this did not prevent his living a lavish lifestyle at Middleton Place. At the time of his death, his holdings included Combahee plantation, Pon Pon, Cedar Grove, Middleton Place, a house in Charles Town and 745 slaves.

Arthur Middleton and his wife had nine children. He died in January 1787 at the Oaks plantation in St. James Goose Creek Parish and was buried in the family mausoleum at Middleton Place. 265

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney: Signer of the U.S. Constitution

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the older brother of Thomas Pinckney, was born in 1746. After Westminister School, Pinckney graduated from Christ Church, Oxford, and studied law at the Middle Temple. He continued his education in France and was called to the English bar in 1769. Upon returning to Carolina, he was called to the South Carolina bar in 1770. He served in the Royal Assembly from 1769 to 1775, when he became a member of the first South Carolina Provincial Congress. He represented St. Philip and St. Michael from 1776 to 1778 in the lower house of the state legislature.

During the Revolutionary War, Pinckney fought at Fort Moultrie and then traveled north to become aide-de-camp to General George Washington. Pinckney’s time on Washington’s staff helped his development as a national leader after the war. He commanded a regiment in the disastrous Florida Campaign of 1778. He participated in the Siege of Savannah and commanded Fort Moultrie during the Siege of Charles Town. When the city fell, he was imprisoned at Snee Farm, the home of his cousin Charles Pinckney. When he rebuffed his captors, he was sent to Philadelphia.

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina .

Pinckney was a South Carolina delegate to the Constitutional Convention and a delegate to the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution. He turned down numerous governmental posts to remain in Carolina, where he and Edward Rutledge were the leaders of the state’s most powerful political faction. In 1796, he accepted President Washington’s appointment to succeed James Monroe as minister to France. When the French Directory refused to accept his credentials, Pinckney left the country in disgust. The following year, he, John Marshall and Elbridge Gerry went to France. When a French government functionary tried to solicit a bribe, Pinckney uttered the famous line, “Millions for defense, Sir, but not one d----d penny for tribute.” The XYZ Affair made Pinckney a Federalist Party hero. He ran unsuccessfully as its candidate for vice president in 1800 and ran unsuccessfully for president in 1804 and 1808.

Pinckney devoted his last years to charitable and civic endeavors. He was a founder of South Carolina College, now the University of South Carolina. He was president of the South Carolina Jockey Club, president of the Society for Relief of Widows and Orphans, president of the Charleston Library Society, president of the Charleston Bible Society and president of the Society of the Cincinnati of the State of South Carolina.