2

THE RISE OF THE SECOND KU KLUX KLAN

The Wood County Ku Klux Klan “held sway in Bowling Green” on the night of October 4, 1923. The group drew between “fifteen and twenty thousand people” to a KKK recruitment event, according to a report by the Daily Sentinel-Tribune. The KKK parade, which contained several marching bands and Klansmen on horses, “stretched out over a distance of a half a mile” in length.20

A fireworks extravaganza and the burning of “four huge crosses” brought the “mammoth meeting to a close.” The Sentinel-Tribune reporter estimated the center cross to be over “forty feet high,” and the reporter carefully detailed his estimation that “some 17,900 people” filled the Wood County Fairgrounds.21

To provide perspective, the crowd attending the Klan event represented a mass of people about two-fifths the size of the entire population of Wood County at the time. While at least half of the attendees were from surrounding counties, to the objective viewers on the ground, this was an unprecedented political event. How, then, did a relatively small Ohio farming region become such a major center of Klan activity in the 1920s?

A 1923 Ku Klux Klan parade. Ohio Historical Society.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE KU KLUX KLAN

The history of the Ku Klux Klan is typically divided by scholars into three distinct phases, each with unique characteristics and areas of focus. The first phase of the Klan is associated with the political violence that took place in the South in response to Reconstruction, running from roughly 1865 to 1874. The Klan’s second phase generally dates from 1915 to the end of the Second World War, while the third phase of the Klan emerges during the height of the American civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s through the present day.22

The first Ku Klux Klan is the terror-based vigilante organization that emerged in the South after the Civil War. These were loosely connected bands of insurgents who used political violence to oppose what they viewed as northern infringement on southern political rights.

The origin of the name “Ku Klux Klan” is somewhat murky. The founders of the first wave of the Klan blended the Greek word kuklos (“circle”) with “Klan” to create the alliterative name. A number of the group’s rituals share similarities with Kuklos Adelphon, which was a southern college fraternity that operated in the decades before the Civil War. The fraternity had faded in popularity by midcentury, and by the 1870s, Kuklos Adelphon had ceased to exit.23

Typically, this first wave of Klan activity targeted politically active African Americans and white Republicans who sought to reshape the South during Reconstruction. While the formal structure of the first Klan was broken in the 1870s, lynchings and other violence by individuals sympathetic to the philosophies of the Ku Klux Klan continued up to the end of the nineteenth century. Groups such as the Red Shirts and the White League carried on the tradition of political violence that the first Klan unleashed. Over the course of the first phase of the Klan and its successor organizations, several thousand people were murdered by members or affiliates of—or individuals in sync with—the Invisible Empire.

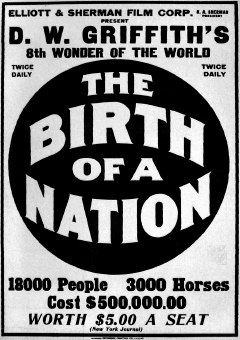

The Ku Klux Klan reemerged in the early twentieth century, in part due to sympathetic portrayals of the KKK in books and other media. Of particular importance in the rebirth of the Klan was Birth of a Nation, the 1915 film by D.W. Griffiths that was based on a 1905 novel by Thomas F. Dixon Jr. entitled The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan. In the film, Griffiths portrayed African Americans as lazy, drunken and oversexed buffoons. Conversely, the film depicted the Klan as a heroic group simply trying to restore order and morality in the post–Civil War South.

Poster of the film The Birth of a Nation. Author’s collection.

More than any other single factor, the film Birth of a Nation solidified the public image of the Ku Klux Klan as a bastion of morality and virtue, regardless of the unpleasant realities surrounding this terror-oriented group and its history of violence and intimidation. Tens of millions of Americans watched the film in the years after its release, giving a wide audience to this work of pro-Klan propaganda.

The creation of the second phase of the KKK was largely the brainchild of William Joseph Simmons, an Atlanta man who bounced around in a variety of careers before finding some financial success as a field organizer for fraternal organizations like the Woodsmen of the World. Simmons found inspiration for his revived version of the Ku Klux Klan in Birth of a Nation, and he also found useful for recruitment efforts the mob lynching of Leo Frank, a Jewish man convicted of murdering a thirteen-year-old girl. Frank’s killers, who included many prominent political leaders, abducted him from a jail in Marietta and drove nearly seven hours across back roads in Georgia before hanging the man in the town of Milledgeville.24

The initial Klan group that Simmons formed included a few members of the Leo Frank lynch mob as well as two elderly men who claimed to be members of the first Ku Klux Klan. As part of their formation rituals, and also to generate publicity for the new Klan, the group climbed Stone Mountain and burned a large cross that was visible for several miles.

The group that Simmons formed grew slowly, numbering just a few thousand members by 1920. The second Klan under the direction of Simmons remained largely confined to the areas around Atlanta. Simmons hired a pair of public relations specialists, Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke, to boost the group’s membership. The Southern Publicity Association—the firm owned by Tyler and Clarke—produced immediate results for the Klan, and membership in the Klan skyrocketed.

The rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan in the early twentieth century was as much a business success as it was a social, cultural and political phenomenon. The Klan under the direction of Tyler and Clarke adopted an incentivized business model in which recruiters—known as kleagles at the local level—were paid a sizeable portion of the initiation fees of new members in exchange for their efforts to boost membership. From the $10.00 membership fee, $4.00 went to the kleagle when he signed a new member, $1.00 went to the King kleagle (regional recruitment leader), $0.50 went to the Grand Goblin (the state recruitment leader) and the remaining $4.50 was remitted to the national office in Atlanta.25

At its peak in the mid-1920s, the Ku Klux Klan boasted as many as 5 million members across the United States, and the group emerged as a powerful political force in many states. In Ohio, one of the Klan’s strongest realms, membership likely peaked at over 300,000 Klansmen by 1925, and some estimates suggest that as many as 400,000 Ohioans had joined the Klan by mid-decade.26

Attacks by opponents of the Ku Klux Klan actually seemed to bolster the popularity of the group, at least temporarily. The period of the highest membership growth appeared after a 1921 New York World exposé on Klan activities that prompted a 1922 congressional investigation of the Klan. Instead of derailing the growth of the Ku Klux Klan, these events enhanced the appeal of the group as a patriotic vehicle for ordinary Americans to exercise their political views.27

Oil worker, oil derrick and cornfield in 1920. Center for Archival Collections.

This second phase of the Ku Klux Klan was much broader in its appeals to tradition-minded white American Protestants, and the Klan expanded its targets to include such groups as Jews, Catholics, immigrants and occasionally left-leaning labor and political activists. The early twentieth-century reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan also demonstrated an ability to adapt to local conditions and to tailor its appeal to local and regional concerns. The clichéd aphorism “politics is local” is especially accurate in helping to understand the appeal of the second phase of the Ku Klux Klan.

Understanding the worldview of members of the second phase of the Ku Klux Klan requires twenty-first century readers to set aside present-day moral beliefs and delve into what was “normal” by the standards of the 1920s, at least what was in the realm of “normal” for white Protestants of Anglo-Saxon heritage. The Klan tapped into existing prejudices and beliefs to promote ideologies based on the following general notions:

That there existed a racial hierarchy in which whites of Anglo-Saxon heritage were at the top level.

That “lesser” races needed to be controlled, developed and supervised by whites.

That there existed a conspiracy by Roman Catholics to reinstate the Pope as the supreme power on Earth.

That Jews dominated important industries such as banking and entertainment and that these powerful Jews sought to debase otherwise morally impeccable whites.

That the United States of the 1920s was in a state of moral, political and social crisis, as evidenced by increases in criminal activity.

That there were imminent—though vaguely defined—threats to the future of the American political system.

Cover of “America for Americans” pamphlet. Author’s collection.

Some scholars attempt to minimize the importance of white supremacist ideology in Klan recruiting efforts during the 1920s. However, Klan recruitment materials do not attempt to hide the fact that the Klan promoted white supremacy. America for Americans was a recruiting pamphlet widely distributed in Wood County in the mid-1920s. The pamphlet declared that “the distinction between the races” was “decreed by the Creator” and that prospective Klan members were required to promise to “be true in the maintenance of White Supremacy.”28

The second phase of the Klan differed from its earlier incarnation in other ways. In addition to nativist political sentiments, the new Klan also emphasized its role as an arbiter of public morality. Among the most important of the moral issues exploited by the Ku Klux Klan was that of Prohibition, and many Klan chapters attempted to gain legitimacy through efforts—legal as well as illegal—to help law enforcement officials curb the underground trade in alcoholic beverages.

In addition, this regenerated version of the Klan also contained a fraternal component: the second Ku Klux Klan was a secret society with a complex organizational structure, intricate symbolism and clandestine rituals. New inductees to the Ku Klux Klan may have been as enticed by the financial, social and political benefits of joining an organization with millions of members as they might have been by the group’s radical ideology. This was a time before safety nets such as Social Security and unemployment compensation, and many American men joined fraternal organizations to protect their families in case of severe financial need.

One of the principal areas of focus for the second Ku Klux Klan was the use of public schools as expressions of the organization’s political will. In part, this was an effort to promote what Klan leaders viewed as vital American values (i.e., white Protestant morality), but this was also a means of undermining the Catholic parochial school systems.

A 1924 editorial in the Wood County Republican highlights another aspect of the Klan’s support of public schools. Citing a study that suggested that there were at least four million illiterate Americans at the time—and “many other semi-educated people who should be placed in the same class”—the author argued that “these ignorant citizens are numerically strong enough to control almost any national election.” The problem of illiteracy, intoned the writer, was a “menace to the welfare of America.”29

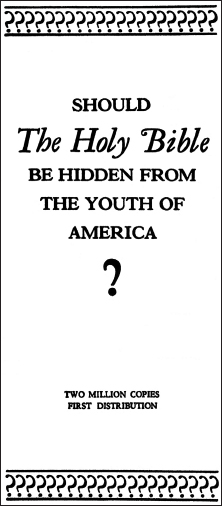

The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s saw public schools as reinforcing the ideals of its “100 Percent Americanism” ideology, and in Ohio, this was especially reflected in the group’s support of the 1925 Buchanan-Clark Bible Reading Bill. This law, passed by the Ohio legislature but ultimately vetoed by Governor Vic Donahey, required public school teachers in the state to read Bible verses to their students each day while also requiring older students to commit to memory the Ten Commandments. Donahey, commenting on his decision, argued that the Bible Reading Bill “opposes the principles of civil and religious liberty.”30

Many residents in Wood County strongly supported the Bible reading legislation. An editorial in the Wood County Republican called for readers to “continue their fight for the sort of education that does not leave Christ out of the life of the person educated.” Moreover, argued the editorial writer, with a sufficient number of public schools “in which the Bible is read and studied, it is likely that the crime problem in America will solve itself.”31

Cover of Should the Holy Bible Be Hidden from the Youth of America? Author’s collection.

A Ku Klux Klan pamphlet widely distributed in Wood County during the Bible bill debate argued that “the Holy Bible advances civilization.” In addition, observed the author of the pamphlet, “future Presidents as well as public servants in their tender age are now in public schools.” Opponents of the Bible bill, according to the pamphlet author, were “intolerant,” “un-American” and possibly “Communists.”32

Three other bills were introduced between the years 1923 and 1925 by Ohio legislators who were either Klansmen or Klan-supported. These included efforts to force students in parochial schools to attend public schools (an obvious attack on Catholics), to ban Catholics from teaching in public schools and to make it a criminal offense for ministers to marry a white person and a nonwhite person. While each of these bills failed to pass the legislature, they served as evidence of the growing power of the Ohio Ku Klux Klan to influence the political sphere.

In general, the Klan in Ohio consistently focused on several key goals with regard to public schools. Klan members fought for the prominent display of the Bible and the American flag, and they simultaneously sought to remove any influences they considered “alien” or “foreign.” In particular, textbooks in public schools were scrutinized and subject to replacement based on the supposed “alien” or “un-American” ideologies that Klan members detected in them. A 1924 Wood County Republican editorial argued that public schools’ having regular Bible reading was an ideal way to “Americanize the foreigners and enlighten the people.” Moreover, noted the writer of the editorial, the “enemies of true Americanism are doing everything possible to keep the Bible out of public schools.”33

Workers at Wood County grain elevator, 1924. Center for Archival Collections.

The second phase of the Ku Klux Klan did not burst onto the American scene without philosophical precursors. Racist ideologies, anti-Semitic views, nativist politics and anti-Catholic biases each possessed lengthy precendents in the history of the United States. The resurgent Klan merely provided a convenient vehicle for white Americans (in particular white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant males) to express these views.

This is not to suggest that the Ku Klux Klan in its second incarnation was unopposed in its growth or that the Klan was not a controversial organization that made many Americans apprehensive. Klan organizers knew exactly what they were doing, and they crafted an adaptable organization that reflected existing mainstream white American views, no matter how repugnant these beliefs might seem to a twenty-first-century reader. A July 26, 1924 edition of the Wood County Republican summarized a speech delivered by a national speaker to a large Klonvocation of around two thousand people on farmland outside the city of Bowling Green:

The orator of the occasion was from Virginia…by his fearless dealing with the problems of the present day such as boot-legging, law-breaking, immigration, the race crisis, the financial peril, and the like, he won for himself round after round of applause.34

Klan recruiters and leaders, in a sense, were preaching to the proverbial choir with their ideological messages. The Klan’s white supremacist, nativist, anti-Catholic and law-and-order rhetoric meshed well with existing views held by many white Protestant residents of Wood County in the 1920s.