6

THE WOOD COUNTY KU KLUX KLAN AS PUBLIC SPECTACLE

The three robed and hooded Klansmen carried an eight-foot cross onto property owned by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Earlier, the men covered the wooden cross with burlap and then doused the device with fuel oil. Upon reaching their destination, the men drove the wooden cross into the ground and set it ablaze before driving off in a waiting automobile.

The flames leapt into the night air of the small town of North Baltimore, Ohio, and the conflagration caught the attention of the railroad facility’s night watchman as well as diners at a nearby restaurant. At the top of the cross was a tin plate that contained the inscription “K.K.K.”

It is unclear who the Klansmen intended as the recipient of their message. The Wood County Republican noted that the Klan “has been active in attempting to eliminate the bootleggers,”143 so perhaps the group knew of some nearby activity in the illegal alcohol trade. It is also possible that a group of transients had been living near the railroad yard and that the burning cross was an attempt by the Klan to terrorize migrants into leaving the area. Whatever the reasons for the placement of the flaming cross, the message was not missed by the citizens of Wood County. The Klan had arrived, and the group meant to impose its collective will on the area.

The Wood County Klan made significant use of highly visible activities during the 1920s. In part, this was simply publicity to build its membership rolls, as well as to provide visceral entertainment for members. However, activities such as cross burnings, Klonvocations, parades and church “visits” (derisively termed “invasions” by at least a few unhappy members of local churches) served as not-so-subtle terror tactics to keep anti-Klan forces at bay.

PUBLIC KLAN SPEAKERS AT OPEN MEETINGS

One of the most important recruitment tools used by the Wood County Ku Klux Klan was the use of large outdoor open meetings. The Klan utilized speakers from regional and national KKK circuits to provide curious residents of local communities an opportunity to hear the group’s message in a more casual setting, and frequently Klan members and their family members from far away attended the event to create a larger crowd. Often these events included family-friendly social activities, such as band music, food concessions and games.

An outdoor Klan meeting on August 10, 1924, featured a speaker from the national headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan. The Wood County Republican reporter who attended the rally, held at a place known as Finney Grove, noted that “one thousand men attended” and that “five hundred automobiles lined the borders of the field.” As a result of the meeting, “a goodly number of real men signed their intention of becoming a part of the movement.”144

In the same week, similar outdoor meetings were held in Tontogany, Cygnet and Prairie Depot featuring national speakers. The Wood County Republican reporter observed that the meetings were “very satisfactory” and that “gratifying results” occurred in terms of recruiting potential members.145

A Klan event at Pemberville on September 12, 1923, brought a “mammoth crowd” to hear a national lecturer speak. The reporter for the Wood County Republican observed that “five hundred men,” all of whom were “true Americans,” inked their names to a charter sheet in the hopes of “becoming a part of the greatest movement ever attempted to protect the American home and school.”146

The first public naturalization ceremony of the Wood County Klan took place on September 10, 1923, just outside the city North Baltimore. The Wood County Republican reported that “five hundred real American men took the oath of allegiance” that evening. The reporter also claimed that “one thousand Klansmen were in attendance” as both spectators and event security.147 The event was capped off with the burning of three crosses, one of which was thirty feet in height, plus the burning of large wooden representations of the letters KKK.

The Klan staged a large public meeting in the village of Bloomdale on the evening of August 6, 1924, that—according to the correspondent for the Bloomdale Derrick—was the “biggest crowd in Bloomdale in a long time.” The event resulted in heavy traffic, and a nearby fallow field “was filled full of automobiles besides the large number that were parked on the street.” The event included a band playing popular music plus a refreshment tent with food, beverages and ice cream.148

CROSS BURNINGS

The ritualistic use of cross burnings by the Ku Klux Klan owes much to the influence of popular culture. There are no documented records of crosses being burned by the first wave of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction, and it appears that the 1905 book The Clansman and the 1915 film Birth of a Nation served as the inspirations for the second wave of the Ku Klux Klan to take up the fiery cross.

The Klan that emerged during the decade of the 1920s had a problematic relationship with cross burnings. On one hand, a burning cross was an effective symbol of terror to opponents as well as a source of inspiration to some onlookers, especially new Klan members and potential Klan recruits. On the other hand, the burning of a cross also focused negative attention on the group from non-Klan local authorities and concerned citizens. The Klan would be forced to tread lightly with regard to cross burnings, alternating between wholeheartedly embracing the practice and occasionally denying the group’s participation in the activity depending on the particular circumstances of a given cross burning event.

Frequently the Klan and its apologists would deny the group’s involvement in cross burnings. After an August 1924 cross burning near a Catholic Church in Bowling Green, the editors of the pro-Klan Wood County Republican opined that the idea that the Klan was responsible for the incident was “positively pronounced an untruth” and that the burnt crosses were merely an attempt by Klan opponents to put “the organization in a more unfavorable light in the eyes of the public.”149

Yet Klan denials of cross burnings are difficult to believe. The burning cross was a powerful symbol evoked in a wide variety of Klan literature and imagery. One need only look at the masthead of The Fiery Cross, a Ku Klux Klan newspaper with wide circulation in the 1920s. Not only did the Klan newspaper adopt as its name a variation of a burning crucifix, but the logo also included an image of a hooded Klan knight carrying a flaming torch. While Klan officials might not have authorized every burning cross, at the same time it is clear that individual Kluxers understood the power of the burning cross to terrorize perceived enemies.

Compare, for example, the coverage by the Wood County Republican of a cross burning that took place at midnight on Christmas Eve in 1923. The front-page article noted that “Christmas was ushered in by the burning of a 20-foot cross and the explosion of a number of aerial bombs” by approximately 150 Klan members. The Klan’s holiday festival took place on Dixie Highway just north of the city of Bowling Green, where the Kluxers had gathered to “celebrate the breaking of Christmas morn.”150

In both cases, cross burnings were accompanied by explosive devices, yet when there was significant concern expressed by local citizens about the first incident, the Klan quickly denied any involvement with the activity. Instead, unknown anti-Klan forces were accused of imitating Klan rituals to discredit the group, though it is difficult to identify a group other than the Klan that had a history of such activity.

Catholics in Bellevue were the target of a similarly threatening cross burning on April 9, 1923. A North Baltimore Times reporter noted that the fiery cross burned “in the sight of hundreds of shoppers” along Main Street. Of particular note is that the burning cross within fifty yards of both St. Augustine Church and the local Knights of Columbus. The incident auspiciously occurred, noted the Times reporter, on the “eve of the initiation of a large class of Knights of Columbus.”151

One of the strangest—and perhaps most threatening—uses of the burning cross by the Wood County Klan took place on April 2, 1923. Klansmen ignited a burning cross on public school grounds in the town of Bloomdale after a performance of the operetta Miss Cherry Blossom.

The plot of the theatrical production involved a young American girl living in Japan whose parents died of an unidentified fever. The girl was brought up in a Japanese family not knowing of her true origins until later in life. While the production has an ending where the girl returns to America and marries a handsome young man, evidently anti-Japanese sentiments among Klan members were sufficiently intense that this plotline offended their sensibilities.

The cross burning took place after the performance, suggesting that the Klan intended people leaving the show to see the fiery crucifix. Klan members also left behind a silk flag after the performance, ostensibly as a not-so-subtle reminder that school officials ought to be focusing on “100 Percent American” themes in future theatrical productions.152

THE KLAN AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

One of the principal concerns of the second wave of the Ku Klux Klan was the improvement and expansion of public schools. Klan ideology viewed public schools both as a counterweight to Catholic parochial schools and as a means to better assimilate immigrants. Public schools, Klan members believed, were the most important tool to promote and reinforce the values they associated with white Protestant nationalism.

One of the methods the Wood County Ku Klux Klan used to strengthen its connections with public schools was through the use of school visits by hooded and robed members. Typically these prearranged visits involved ritual and ceremonial activities to emphasize the sincerity and seriousness of the Klan, and most visits also included gifts to the school such as flags and Bibles.

Klan visits to schools served an additional purpose, namely that of publicity for the group. Children certainly would have recounted the visits to their parents upon returning home from school, and parents—whether outraged by the visit or sympathetic to the Klan cause—would have naturally discussed the incidents with family members, neighbors and co-workers.

The Perrysburg Journal reported on a December 5, 1923 Ku Klux Klan visit to Perrysburg High School. Students were attending a morning religious service in the school chapel when “they were somewhat surprised and awe-stricken” by the arrival of a contingent of Klan members to the service.153

The eight hooded and robed Klansmen staged a procession down the aisle where they were greeted by Chalmer B. Riggle, superintendent of Perrysburg Public Schools. In addition to a “good sized Holy Bible,” the Klan presented the school with an eight-by-twelve-foot American flag. After singing the patriotic song “America,” the Klansmen processed silently out of the chapel.154

As was the case with similar church visits by Klan members, often the visits by Klansmen to public schools were enabled by insiders. In the case of the Perrysburg High School incident in 1923, fellow Klan member Chalmer B. Riggle likely played a role in arranging the visit, and he also presumably helped arrange similar Klan visits to Perrysburg schools in 1924.

Ku Klux Klan members visit Perry School to present a gift of the American flag, 1928; this is one of the few surviving photographs of the Wood County Klan. Center for Archival Collections.

About fifteen Klan members posed with the students and staff of the school for the photographer on the chilly morning. The Klan presented school officials with a flag and a Bible, and they participated in a ceremony in which the three-by-five-foot American flag was unfurled and raised on the flagpole. Klan members led the students and staff in a brief prayer before marching in procession back to their automobiles.

KLAN FUNERALS

The death of a Klansman provided the Klan with a different type of publicity opportunity. Klan members frequently used funerals as occasions for displaying Klan regalia and creating elaborate processions through the communities in which the group operated.

One such Klan funeral occurred with the death of Howard L. Homes, a railroad worker from Toledo who was crushed by a locomotive. Homes lived long enough to request that his body be transported to his boyhood home in Arcadia, Ohio, a town just south of the Wood County border.

Hundreds of Klan members from Toledo traveled in eighty-two vehicles, according to the reporter from the Wood County Republican. At the Wood County line they were joined by a large contingent of Wood County Kluxers, and later, Klan members from the city of Findlay joined in a funeral procession that was “three miles in length.” The procession included a performance by the Toledo Klan band.155

The North Baltimore Times reported a Klan grave visitation that occurred in the town of Bettsville on May 21, 1923. Eight Klansmen traveled across the county line to the Old Fort Cemetery to pay tribute to a fallen Klan comrade who had died of unidentified causes a week earlier. The Klan delegation marched into the cemetery carrying an American flag and a cross covered with red roses. The Kluxers planted the cross at the “foot of the grave, kneeling and praying silently and spreading carnations on the mound.”156

Members of the Wood County KKK staged a more elaborate Klan funeral in North Baltimore for Harold L. Jones, a nineteen-year-old man who “was taken from this earth suddenly Friday noon while conversing with his mother.” Jones, according to the North Baltimore Times, “had only been a member of the Klan for a short time but had made himself felt as a true American citizen during his membership.” Klan members provided the ceremony with a “beautiful Fiery Cross floral piece” as part of their collective condolences. The North Baltimore Times account described the efforts by the Klan members to memorialize their fallen comrade:

The Klansmen gathered in the southern part of the cemetery, and after all ceremonies were performed, marched with silent tread, arms folded (masked and robed) each one carrying a white carnation, after gathering around the grave the members knelt in silent prayer for a short time, then arose and with outstretched hand paused a moment, then deposited the carnations on the grave. This done, they returned as silently as they came, disrobed, and returned to their homes, mourning the loss of so young a life, but all with one thought in mind: “God’s will be done.”157

Funerals for deceased Klansmen served several purposes for the Wood County Klan. The presence of Klan members at the graveside or funeral home reinforced the idea that the Klan was a benevolent fraternal organization dedicated in part to assisting the families of Klansmen in times of need. The public demonstration of solemnity helped communicate the strong religious character of the Klan, perhaps mitigating in the eyes of some spectators the strong white supremacist views of the group. Finally, Klan funerals helped perpetuate the idea that the Ku Klux Klan was a powerful group that seemed to influence every aspect of American life.

KLAN THEATRICAL PRODUCTIONS

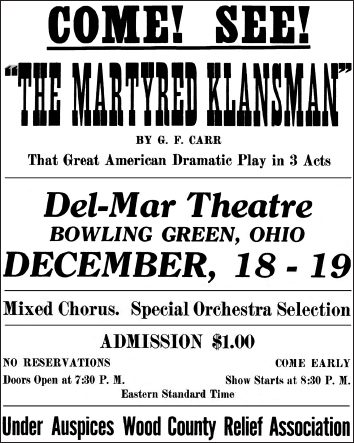

One of the more unusual public spectacles sponsored by the Wood County Ku Klux was a December 1924 theatrical production entitled The Martyred Klansman. The show was a three-act play based on a piece of Klan propaganda by the same name that was loosely based on the death of a Klan member during a riot in Carnegie, Pennsylvania.

Advertisement for the “Martyred Klansman.” From the Wood County Republican.

The script for the production was written by a Marion, Ohio Klansman named G.F. Carr. A small traveling troupe of Klan actors served as the core for the cast of characters, and a handful of local Klansmen had roles as extras.

The Klan benefited from having additional connections in the entertainment industry. The owner and manager of the Del-Mar Theatre in Bowling Green was Clark M. Young, who joined the Klan at the beginning of 1924. The Del-Mar facility was also used for numerous larger Klan events over the next two years in the mid-1920s.

Young’s participation in the Klan was likely a precarious one, given the denunciations that the Klan frequently levied against what the group termed the “Jew-owned entertainment industry.” Perhaps Young enthusiastically embraced Klan ideology, but it is equally likely that Young decided that joining the Klan was a way to avoid having his theater threatened by angry Klansmen should his theater end up showing a film that the Klan found immoral or offensive.

The Klan booked the show for two nights, and advertisements indicated that proceeds from the event would benefit a Klan charity known as the Wood County Relief Association. Unfortunately, due to “the closeness to Christmas,” as well as “the extremely wet weather on Thursday night turning to very cold on Friday night,” the number of people who attended the show fell far below the expectations of Klan organizers.158

CHURCH INVASIONS

One of the most effective public tactics used by the Wood County Klan was the use of church visits, derisively referred to as church “invasions” by opponents. Typically, a group of hooded Klansmen entered a particular church in the middle of a service and publicly presented the church with a “gift,” usually in amounts between twenty and fifty dollars. Many times the Klan would prearrange such visits with the minister, though sometimes these visits were unannounced.

A 1923 Ku Klux Klan visit to the Rudolph Church of Christ was typical of the format for church spectacles involving Klansmen. Just before the sermon by Reverend C. Faun Leiter, a small group of hooded Klan members silently entered the church and marched in procession down the aisle. The Kluxers were met at the lectern by Reverend Leiter, who accepted a fifty-dollar cash donation. The Klan members departed the church after leading the congregation in a short Bible reading and prayer.

Reverend Leiter, it should be added, had become a Klan member by at least January 1924, and if he was not officially a member before the Klan visit, he certainly was sympathetic to their cause, at least in the version of the event printed by the Wood County Republican. In his sermon, Reverend Leiter discussed the “good works” that the Ku Klux Klan had been engaged in, and he urged members of the congregation to consider membership in the organization.159

Some Klan church visits deviated from the prototype, however, and the term “invasion” better fits some Ku Klux Klan spectacles. Such was the case with the August 5, 1923 Klan visit to the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Circleville. A group of twenty-five hooded Klansmen entered the church during services, marched up the aisle and gave the minister twenty dollars before exiting the church. The invading Klansmen created “much consternation among the dusky folk present,” according to the North Baltimore Times.160

Klan visits to religious facilities associated with African Americans, Catholics, immigrants and/or Jews served several purposes. On one level, this was a somewhat ham-fisted attempt to counter charges that the Klan was a group that promoted hate; after all, if Klansmen hated those who were not white native-born Protestants, why would they give their heard-earned money to these supposed enemies?

A 1923 headline highlighting KKK visit to a black church. From the North Baltimore Times.

Yet clearly a Klan visit to a religious space—such as the Circleville African Methodist Episcopal Church—served a more sinister purpose. Klan members were communicating that they were a force to be reckoned with and that they had claimed for themselves the right to invade even the most sacred spaces of others in order to promote their own views. Given the “consternation” among African Americans observed by the reporter for a newspaper sympathetic to the Klan like the North Baltimore Times, Klan members undoubtedly used these “alien” church visits as a method of intimidating other groups.

KLAN KLONKLAVES

One of the most important public events in the operation and maintenance of a Klan chapter was its participation in large formal KKK meetings. The Wood County Klan referred to these events as “Klonklaves,” though the term has alternately been spelled “Konklave” or “Konclave.” Typically, these involved hundreds and sometimes thousands of members from several regional Klan chapters.

The first official Klonklave that can be documented in Wood County occurred on October 4, 1923. The KKK used the Wood County Fairgrounds as the staging area for the event. The highlight of the evening was a parade that passed through the streets of the city of Bowling Green, and at the front of the parade were a pair of Klan marching bands.161 The Wood County Republican described the size of the parade as “mammoth,” while the Wood County Democrat estimated the number of hooded Klansmen in the parade at 500 marchers.162 A reporter for the Daily Sentinel-Tribune estimated the number of parade participants at as many as 660 people, using a mathematical formula that incorporated a four-mile-per-hour parade speed and the average distance between marchers.163

It is interesting to note that the parade route traveled straight through the neighborhood with the heaviest concentration of Catholic residents. Undoubtedly, this was a provocation to local Catholics, especially given the fact that the parade passed directly in front of St. Aloysius Church and also the meeting place of the Bowling Green Knights of Columbus.

A 1923 Ku Klux Klan klonclave. Ohio Historical Society.

The October 4, 1923 Klonklave attracted people from a wide geographical area. The Daily Sentinel-Tribune reporter spoke with attendees from Toledo, Findlay, Wapakoneta, Napoleon, Lima, Defiance, Bryan and Tiffin as well as other cities. Approximately “210 machine loads” of visitors came from Findlay alone.164

The Wood County KKK held its first major outdoor Klonklave with regional attendance on May 6, 1924. The event occurred on a Tuesday evening, and the reporter from the Wood County Republican noted that the meeting was a “mammoth gathering from all over this section of the state” and that three hundred Knights were naturalized in the ceremony. New Klan initiates walked between a lengthy row of hundreds of hooded Knights on the left and a line of “red fire” on the right, creating a sort of human-flame gauntlet for the candidates to walk as they approached the stage. Klan chapters from several counties were represented at the event.165

The Wood County Klan hosted one of the largest Klonklaves in the history of the state of Ohio on Saturday, October 24, 1924. The Klan hosted its 1924 Klonklave at the Wood County Fairgrounds in Bowling Green, and thousands of members of Klan chapters from Ohio, Indiana and Michigan attended the massive event. Curious onlookers from around the city and county enlarged the size of the crowds.

The Wood County Republican estimated that “from fifteen to twenty thousand persons” took part in the festivities. To put this into perspective, the crowd was one-third to one-half the total population of the county at the time, at least if the newspaper accounts can be taken at face value. The weather was “an ideal October night,” and the Republican reporter suggested that this contributed to the large crowd size.166

The highlight of the Klonklave was a large parade that started at the fairground racetrack and wound its way through the streets of Bowling Green. The Republican reporter observed that “nearly a thousand men and women members of the Ku Klux Klan were in the parade, which was half a mile long.” The parade was headed by three horsemen who were followed by the Toledo Klan Band as well as a Klan drum corps composed of Rossford and Toledo Kluxers.167 Interestingly, the parade route did not take a confrontational route through Catholic neighborhoods; it is unclear if this was a decision made by the Klan or by the city of Bowling Green.

The death of famed politician and lawyer William Jennings Bryan provided the Wood County Klansmen with a reason to stage a well-attended public event in late July 1925. Bryan, who was not a Klan member at any time, nonetheless found himself praised by the Klan due to his efforts to defeat an anti-Klan plank at the 1924 Democratic National Convention.

As a result of this stance on the anti-Klan resolution, which Bryan believed to be a divisive and politically controversial position, he became the object of near veneration by Klansmen. The Wood County Republican described Bryan as “the greatest Klansman of our times,” claiming that Bryan “stood for what was right the same as all honorable Klansmen do and will to the end of eternity.”168

The large crowd that turned out for the Bryan memorial service gathered at “the Les Swindler farm north of the city” of Bowling Green on July 31, 1925. The Klan burned a cross and a Klan band played the song “Taps” for the late politician. The Reverend George Sesious of Findlay delivered a “fine eulogy” for Bryan to the gathered Klansmen and visitors.169

The efforts of members of the Wood County Klan to promote the organization via public spectacle certainly aided the group in its recruitment drives. At the same time, though, such activities also strengthened the resolve of anti-Klan forces while alienating some county residents who might not have otherwise formed negative opinions on the Klan.