INTRODUCTION

The choir and congregation had just finished singing a hymn entitled “The Path of the Just” during an evening service when a group of nine men wearing Ku Klux Klan robes marched into the church. One of the Klan members carried the American flag, while another Kluxer held high a copy of the Bible as the anonymous men entered the house of worship.1

The hooded visitors, parading in formation, continued up the aisle to the altar, where they presented the minister with an introductory letter and a financial contribution to the church.

The Klan group then turned and faced the audience, at which point one of the Klansmen opened the Bible and began reading from the twelfth chapter of the New Testament book of Romans:

Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship. Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will.

The Klan members then directed the congregation to kneel in prayer, at which point, one of the Kluxers led the assembled church members in the Lord’s Prayer. After this impromptu KKK ceremony, the hooded members of the Klan silently marched out of the church and into the chilly February evening air.

This scene likely seems surreal enough to a twenty-first-century reader who is decades removed from the point in time when the Ku Klux Klan was a powerful organization with millions of members. Even stranger, however, is the fact that the above Klan activity took place on February 11, 1923, in the city of Bowling Green, Ohio, at the local United Brethren Church. This event took place not in the Deep South of the Jim Crow era or the height of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, but in a rather sleepy midwestern college town.

The Klan visit to the United Brethren Church was hardly the “surprise” described by the newspaper reporter for the Wood County Republican in its coverage of the event. Word had leaked out prior to the Ku Klux Klan event, as the main auditorium filled and adjacent classrooms had to be opened to accommodate the hundreds of additional visitors that the Klan event attracted.

Most importantly, the Reverend Rush A. Powell, minister of the United Brethren Church, was himself a charter member of the Wood County Chapter of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Reverend Powell welcomed the Klan to Trinity United Brethren Church with open arms, telling the congregation that he “stood for the same principles”2 as those held by his hooded guests. After the Klan Bible reading and prayer, Reverend Powell spoke of the perils the United States faced with criminal activity, undesirable immigrants and a general decline in morality. While not publicly declaring himself a Klan member, Reverend Powell assured his audience that the Klan was formed to address those threats to America.

It is tempting to write off events such as this Klan visit as aberrations in an otherwise forward movement of American history toward greater tolerance and a more inclusive society. Yet Reverend Rush A. Powell was but one of millions of faces of the Ku Klux Klan that emerged in the early twentieth century, and Ohio’s Wood County proved to be a bastion of Klan activity for a lengthy period of time. The Klan, instead of being a fleeting historical anomaly, represented a highly visible face of widespread American intolerance and bigotry.

The Ku Klux Klan took root in Wood County and maintained a significant presence for at least two decades. Its legacy can still be discerned nearly a century after the Klan officially appeared on the landscape of this otherwise quiet, agriculture-dominated region in Northwest Ohio.

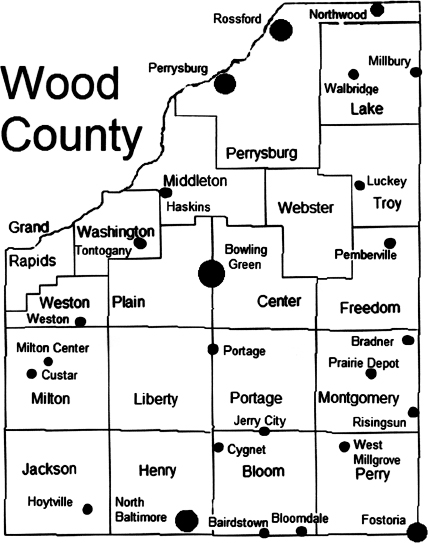

This book examines the rise and fall of the Ku Klux Klan in Wood County, Ohio, an area located in a heavily agricultural region in the northwestern corner of the state. The Wood County klavern was one of thousands of chapters of the Klan that sprang up during the 1920s in the era of the so-called Second Klan, when membership in the organization numbered in the millions in the United States.

Map of Wood County. Michael E. Brooks.

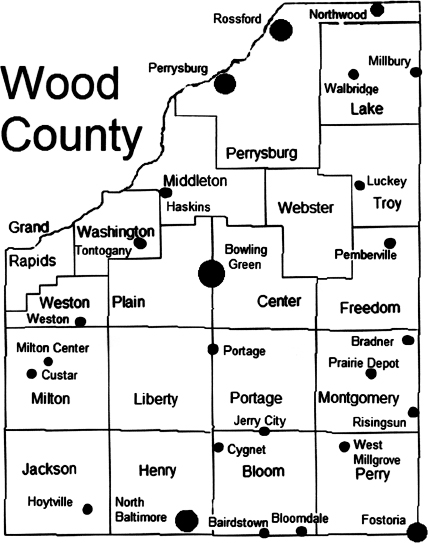

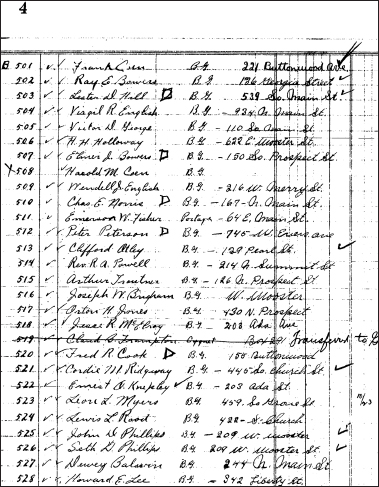

We are fortunate that important records of the Wood County Ku Klux Klan Chapter 107 have survived into the twenty-first century. Given the secretive nature of the organization, detailed membership records of local Klan chapters are somewhat rare, but the Wood County Klan is an exception to that tendency. The core of the research for this book is based on careful study of the meticulous membership and dues registers that Klan officials maintained.

Sample page of the Wood County Ku Klux Klan membership ledger. Center for Archival Collections.

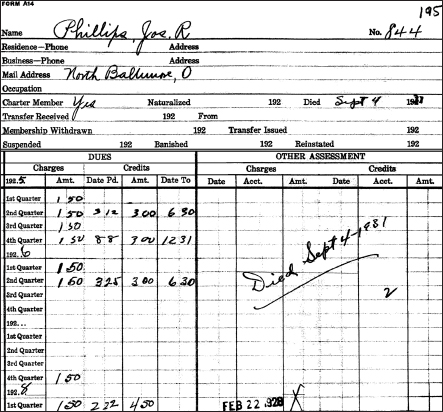

Klan members provided the local chapter with a range of personal information, including names, home addresses, employment information and the name of the person who referred the individual to the group. Klan officials recorded dates of initiation, payment of dues and additional information on banishment, departure or death of the member.

Klan records also contain interesting notes in the margins and unfilled columns of dues, registers and membership files, such as the case of a Klan member banished in 1925. A margin note provided a clue for the banishment: “MARRIED CATHOLIC.”

Other notes included details about Klan members who transferred from (or to) other Klan chapters, members suspended for nonpayment of dues, members who faced financial difficulties, members who received Klan funeral ceremonies or members who moved without leaving forwarding addresses.

Klan membership and dues records were crosschecked against other sources from the time period. These additional sources included census rolls, city directories, newspaper articles, birth and death records and church membership lists. After assembling the database of names and relevant information, analysis of the data was conducted to develop general characteristics of the typical member of the Wood County Ku Klux Klan.

Sample Klan membership card. Center for Archival Collections.

Far from being a temporary aberration, the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in Wood County was in some ways normal for the American Midwest of the 1920s. However, the Wood County klavern of the Klan exhibited its own distinctive characteristics, and Klan leaders in the county carefully tailored the group’s message to local and regional concerns.

The Klan in many ways found a ready-made audience in Wood County for its ideologies of racism, nativism and religious intolerance. While the national recruitment and organization personnel of the Ku Klux Klan helped plant the seeds for the group’s emergence in Wood County, the Klan also benefited from the fertile ground of preexisting racial, religious and political views among many county residents.