4

First-Principles Investigation on the Chemical Bonding and Intrinsic Elastic Properties of Transition Metal Diborides TMB2 (TM=Zr, Hf, Nb, Ta, and Y)

Yanchun Zhou1, Jiemin Wang2, Zhen Li2, Xun Zhan2, and Jingyang Wang2

1 Science and Technology of Advanced Functional Composite Laboratory, Aerospace Research Institute of Materials and Processing Technology, Beijing, China

2 Shenyang National Laboratory for Materials Science, Institute of Metal Research, Chinese Academy of Science, Shenyang, China

4.1 Introduction

Transition metal borides (TMBs) are characterized by high melting points, high hardness, high strength, chemical inertness, effective wear and environmental resistance, and absence of phase changes in the solid state. These properties make them promising for applications in extreme environments such as cladding materials in general IV nuclear reactors, nose tip and sharp leading-edge materials for hypersonic vehicles, sharp edge and hot structure component materials for scramjet engines [1–4], as well as matrix and surface coatings for ultra-high temperature ceramic (UHTC) matrix composites [5, 6].

Despite the unique combination of properties, poor thermal shock and oxidation resistance are the main barriers to their more extensive applications. Previous studies have demonstrated that poor thermal shock resistance of ZrB2 and HfB2 is resulted from their high Young's moduli [7], while the poor oxidation resistance is resulted from the lack of the formation of stable and protective scales on TMBs during high-temperature oxidation [7–9].

The macroscopic properties of TMBs are related to their electronic structure and bonding properties. Quantum mechanical modeling of solids through first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) has proven to be a powerful tool to obtain microscopic information that is helpful in understanding the macroscopic properties of solids. Predicting functions and properties of materials from first-principles is also helpful in scanning the properties of materials and accelerating materials development and application processes [10]. Thus, investigation of electronic structure, bonding nature, and intrinsic properties of the TMBs is essential to understand various properties of TMB2 and to design new compositions/composites as well as to stimulate the applications of UHTCs.

The electronic structure and bonding properties of TMBs were previously investigated by several research groups [11–13]. Vajeeston et al. [11] calculated the electronic structure, chemical bonding, and ground-state properties of AlB2-type transition metal diborides TMB2 (TM = Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Y, Zr, Nb, Mo, Hf, Ta) using self-consistent tight-binding linear muffin-tin orbital method. Lawson et al. [12] investigated the electronic structure, elastic properties, and specific heat of ZrB2 and HfB2 using the plane wave DFT codes VASP [14] and ABIBIT [15]. Shein and Ivanovski [13] calculated the elastic properties of hexagonal AlB2-like diborides of s, p, and d metals using first-principles calculations. Despite the contribution of these studies, understanding of the anisotropic chemical bonding and anisotropic mechanical properties of TMBs is still lacking. Since large-size single crystals of TMBs are not available, theoretical predications on the anisotropic mechanical properties from DFT computations could be very useful in understanding the performance and compositional design of UHTCs. In this work, the electronic structure, chemical bonding nature, and mechanical properties of some TMBs including YB2, ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 were investigated using first-principles calculations. These borides were selected because of their technological importance and because the number of valance electrons systematically changes from 3 for Y, 4 for Zr and Hf, and 5 for Nb and Ta such that a general trend on the change of electronic structure and intrinsic mechanical properties can be obtained. Anisotropic chemical bonding nature in YB2, ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 was disclosed by studying the pressure dependence of lattice parameters and bond lengths, and by analyzing their band structure, density of states (DOS), electron density difference maps, and charge density. The anisotropic chemical bonding properties resulted in high Young's moduli in x and y directions, but relatively low Young's modulus in z direction. By comparison of the Young's modulus, YB2 is predicted to have better thermal shock resistance. By the comparison of the ratio of shear modulus to bulk modulus, G/B, TaB2 is predicted to be a possible damage-tolerant UHTC.

4.2 Calculation Methods

The valence states considered in the present calculations are 2s2 and 2p1 for boron, 4d15s2 for yttrium, 4d25s2 for zirconium, 5d26s2 for hafnium, 4d45s1 for niobium, and 5d36s2 for tantalum. The first-principles calculations were performed using the CASTEP code [16], wherein the Vanderbilt-type ultrasoft pseudopotential [17] and generalized gradient approximation [18] (PBE) were employed. The plane wave basis set cutoff was 360 eV for all calculations. The special points sampling integration over the Brillouin zone was employed by using the Monkhorst Pack method with a 9 × 9 × 8 special k-points mesh [19]. To investigate the anisotropic bonding nature, equilibrium crystal structures were optimized at various isotropic hydrostatic pressures from 0 to 70 GPa. Lattice parameters were modified to minimize the enthalpy and interatomic forces. The Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno minimization scheme [20] was used in geometry optimization. The tolerances for geometry optimization are different on total energy within 5 × 10−6 eV/atom, maximum ionic Hellmann–Feynman force within 0.01 eV/Å, maximum ionic displacement within 5 × 10−4 Å, and maximum stress within 0.02 GPa. The calculations of the projected DOS were performed using a projection of the plane wave electronic states onto a localized linear combination of atomic orbitals basis set.

The full set of single-crystal elastic coefficients were determined from a first-principles calculation by applying a set of given homogeneous deformations with a finite value and calculating the resulting stress with respect to optimizing the internal degrees of freedoms, as implemented by Milman et al. [21, 22]. The criteria for convergence in optimizing atomic internal freedoms were selected as follows: difference on total energy within 5 × 10−6 eV/atom, ionic Hellmann–Feynman forces within 0.002 eV/Å, and maximum ionic displacement within 5 × 10−4 Å. The elastic stiffness was determined from a linear fit of the calculated stress as a function of strain, cij = (∂σi(x)/∂εj)x. Variations in the stress tensor (σi) due to applied strain (εj) were calculated to obtain an elastic stiffness constant (cij). Both positive and negative strains were applied in the elasticity calculations. The compliance tensor S was calculated as the inverse of the stiffness tensor, [S] = [C]−1. The polycrystalline bulk modulus B, shear modulus G, and Young's modulus E were estimated from the single-crystal elastic constants, cij, according to the Voigt, Reuss, and Hill approximation [23–25]. A detailed formula for these calculations is given in Section 3.3.

4.3 Results and Discussion

4.3.1 Lattice Constants and Bond Lengths

Transition metal diborides TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta) crystallize in an AlB2-type structure with the space group of P6/mmm (No. 191). Transition metal atoms are located at 1a (0,0,0) Wyckoff positions, and boron atoms are located at 2d (1/3,2/3,1/2) Wyckoff positions. Figure 4.1 shows the crystal structure of TMB2. Table 4.1 lists the experimental and geometry optimized lattice constants a and c, c/a ratios and the bond lengths between B and B, and those between B and TM in TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta). The data listed in Table 4.1 show that GGA calculations slightly overestimate the lattice parameters as expected in any study with generalized gradient approximations. The calculated lattice constants a and c of YB2, ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 are close to the experimental lattice constants and also agree with the calculated values given in the previous work [11–13], demonstrating the reliability of the present calculations. It is also interesting to note that the lattice constants depend not only on the atomic size but also on the number of valence electrons of the transition metals. As the number of valence electrons increases from 3 for Y to 4 for Zr and Hf, and then to 5 for Nb and Ta, the lattice constant c decreases continuously; the lattice constant a, however, decreases from Y to Nb, but increases slightly for Ta due to its large atomic size. As a result, YB2 has the largest lattice constants, ZrB2 and HfB2 have intermediate lattice constants, and NbB2 and TaB2 have the smallest lattice constants. The c/a ratio also decreases continuously when TM changes from Y to Zr and Hf, and then to Nb and Ta, that is, c/a ratio decreases with the increased number of valence electrons. The change of TM–B, B–B bond lengths shows a similar trend as the change of lattice constant a.

Figure 4.1. Crystal structure of TMB2.

Table 4.1. Lattice constants and bond lengths of TMB2

| Lattice constants | ||||||

| Compound | YB2 | ZrB2 | HfB2 | NbB2 | TaB2 | |

| aexp (Å) | 3.290 | 3.170 | 3.139 | 3.086 | 3.074 | |

| acal (Å) | 3.326 | 3.171 | 3.166 | 3.107 | 3.136 | This work |

| 3.314 | 3.197 | 3.166 | 3.107 | 3.115 | 11 | |

| 3.17 | 3.15 | 12 | ||||

| cexp (Å) | 3.835 | 3.533 | 3.473 | 3.318 | 3.290 | |

| ccal (Å) | 3.923 | 3.544 | 3.515 | 3.340 | 3.335 | This work |

| 3.855 | 3.561 | 3.499 | 3.328 | 3.244 | 11 | |

| 3.56 | 3.52 | 12 | ||||

| c/a | 1.179 | 1.117 | 1.110 | 1.075 | 1.063 | |

| Bond lengths | ||||||

| Compound | YB2 | ZrB2 | HfB2 | NbB2 | TaB2 | |

| B–B (Å) | 1.920 | 1.831 | 1.828 | 1.794 | 1.811 | |

| TM–B (Å) | 2.745 | 2.548 | 2.538 | 2.443 | 2.467 | |

Another feature is that the TM–B bond lengths are longer than the B–B bond lengths, indicating the anisotropic chemical bonding characters in TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta). To visually illustrate the anisotropic chemical bonding nature and elastic anisotropy, the dependence of lattice constants a and c, and the B–B and TM–B bond lengths in TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta) on hydrostatic pressure was investigated. Figure 4.2 shows the pressure dependence of lattice constants for YB2, ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 up to 70 GPa. For all the diborides investigated in this work including YB2, ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2, the lattice constants a and c decrease continuously with hydrostatic pressure. However, the degree of contraction is different, that is, the compressibility of the TMB2 compounds is in the order YB2 > ZrB2 > HfB2 > NbB2 > TaB2. In other words, the compressibility of the TMB2 compounds decreases as the number of valence electrons increases from 3 for Y to 4 for Zr and Hf, and then to 5 for Nb and Ta. Careful analysis of the pressure dependence of lattice constants a and c in Figure 4.2 shows that for ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2, lattice constant c contracts more dramatically than lattice constant a in the pressure range examined, that is, ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 are stiffer in the basal plane than in c direction; for YB2, however, lattice constant a contracts more rapidly than lattice constant c, that is, YB2 is stiffer in c direction than in the basal plane. This anomalous phenomenon will be explained in later sections based on the electronic structure investigation.

Figure 4.2. Pressure dependence of lattice constants a and c of TMB2.

The strength of interatomic bonding as a function of pressure was investigated by examining changes in TM–B and B–B bond length under various pressures (Fig. 4.3). The degree of bond contraction was in the same order as that of lattice constants a and c, that is, YB2 > ZrB2 > HfB2 > NbB2 > TaB2. Similar to the pressure dependence of lattice constants a and c shown in Figure 4.2, the change of TM–B and B–B bond lengths under hydrostatic pressure can also be divided into two groups. For ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2, the TM–B bond length contracts more rapidly than the B–B bond length, indicating that the B–B bonds in these borides are stiffer, while for YB2, the B–B bond contracts more rapidly than the Y–B bond. The different responses of bond length to hydrostatic pressure reveal different bonding properties in TMB2. In ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2, the B–B bonds are stiffer than TM–B bonds, while in YB2, the Y–B bonds are stronger.

Figure 4.3. Pressure dependence of TM–B and B–B bond lengths.

4.3.2 Electronic Structure and Bonding Properties

In Section 4.3.1, the pressure dependencies of lattice parameters and B–B, TM–B bond lengths were investigated, and different responses of bond lengths to hydrostatic pressure were demonstrated. These behaviors are underpinned by the electronic structure and chemical bonding nature. The electronic structure of TMB2 (TM = Sc, Ti, Cr, Mn, Fe, Y, Zr, Nb, Mo, Hf, Ta) was studied by Vajeeston et al. [11] and that of ZrB2 and HfB2 was investigated by Lawson et al. [12]. However, the anisotropic chemical bonding nature was not emphasized. In this work, the electronic structure and bonding properties of TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta) were disclosed based on the analysis of DOS, band structure, and distribution of charge density on planes across TM, B parallel to (0001), and on (11 20) plane that is across both TM and B atoms.

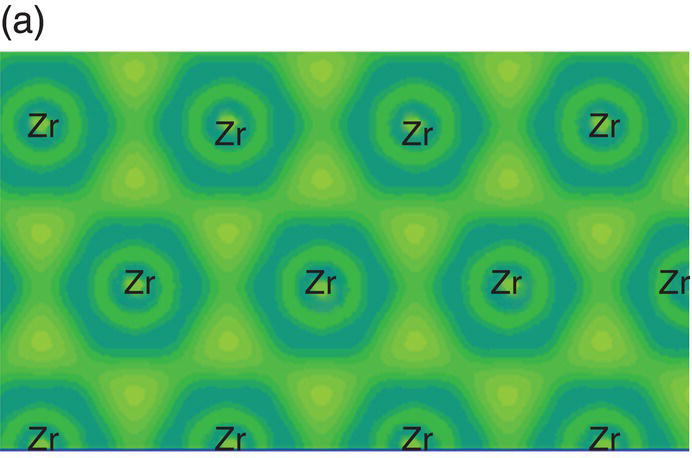

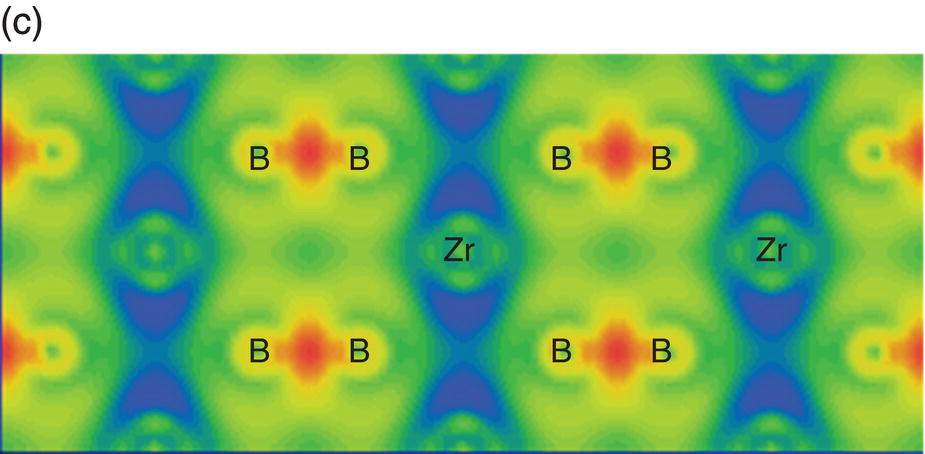

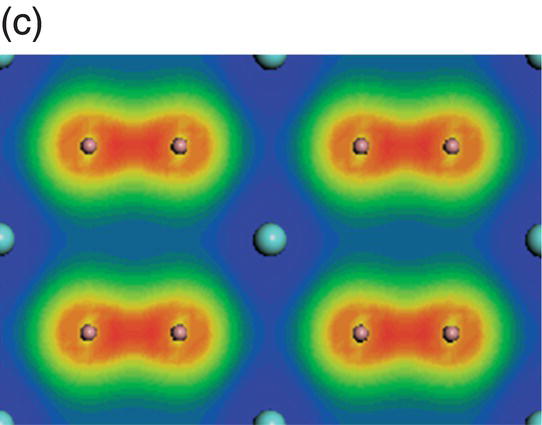

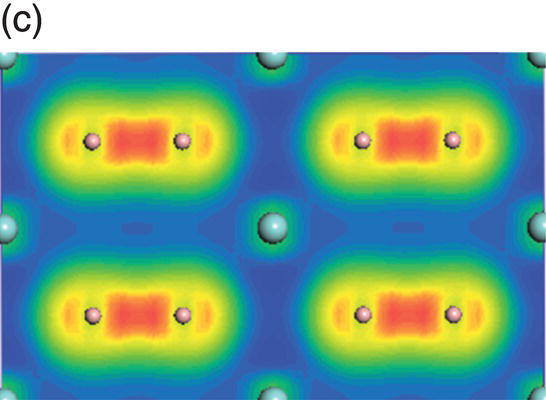

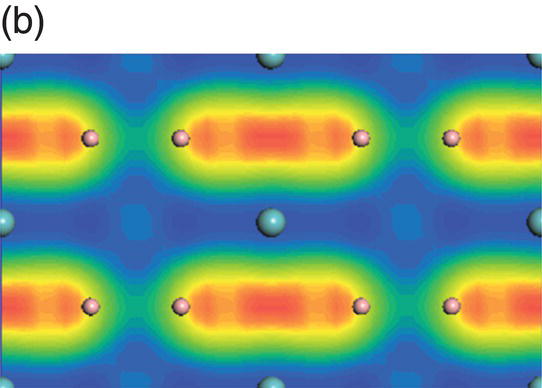

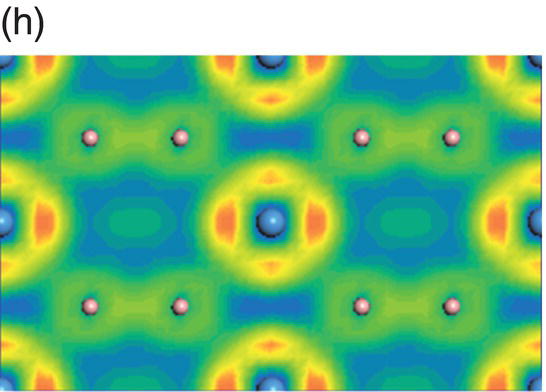

To visually illustrate the chemical bonding in TMB2, the electron density difference maps of these compounds are shown first. Electron density differences produce a density difference field that shows the changes in the electron distribution due to the formation of all the bonds in a system. The electron density difference map illustrates the charge redistribution due to chemical bonding in solids. Figure 4.4 shows the electron density difference maps on planes parallel to (0001) that are across the Zr atoms (Fig. 4.4a) and B atoms (Fig. 4.4b), and on the (1120) plane that contains both Zr and B atoms (Fig. 4.4c). In Figure 4.4a, no localized electrons were observed between neighboring Zr atoms, but triangular accumulation among groups of three Zr atoms can be seen [12], which is typical metallic bonding [31]. That is, the chemical bonding on the Zr plane is mainly metallic. In Figure 4.4b, strong localization is evident between two neighboring B atoms forming a graphitic B-plane with six-membered rings, which is an indication of σ-type covalent bonding formed by the overlapping of hybridized B-sp2 orbitals. This B-sp2 hybridized σ-type covalent bonding is strong and corresponds to the incompressibility of lattice constant a and B–B bond in ZrB2. In Figure 4.4c, strong localization is obvious between the two B atoms, which is the typical π-type covalent bonding through the accumulation of p-orbitals. The valence electrons in B are 2s22p1. The formation of σ-type bonding through overlapping of hybridized B sp2-B sp2 orbitals and π-type bonding through overlapping of B 2pz-B 2pz orbitals indicates charge transfer from Zr to B occurs. Thus, bonding between Zr and B is mainly ionic. However, charge accumulates between Zr and B through interactions between Zr 4d orbitals and B 2p orbitals, as can be seen in Figure 4.4c. That means besides the ionic bonding generally accepted by many researchers [11, 12], covalent bonding also contributes to the Zr–B bonding in ZrB2 so that the bonding between Zr and B is ionic–covalent in nature. It is intriguing to see that the Zr–B covalent bonding is through the hybridization of Zr-4d (eg) and B-2pz orbitals, and the extension of Zr-4d (eg) orbitals in the x–y plane indicates that covalent bonding is stronger in the x-plane than in the c direction. This bonding nature is helpful in understanding the response of lattice constants and bond lengths to hydrostatic pressure shown in Figures 4.2 and 4.3, that is, strong covalent bonding in the basal plane corresponds to stiffer B–B bonds in the basal plane. These results demonstrate that all three types of bonds, that is, metallic, covalent, and ionic bonds, contribute to bonding in ZrB2. The strong covalent and ionic bonding are responsible for its high modulus and strength, while the metallic bonding underpins its good electrical conductivity.

Figure 4.4. Electron density difference maps on planes parallel to (0001) that are across Zr (a) and B (b) atoms, and on (1120) that is across both Zr and B atoms (c).

To further understand the electronic structure, band structures of TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta) were calculated and are depicted in Figure 4.5. Figure 4.5a shows band dispersion curves along some high-symmetry directions in the Brillouin zone of YB2. The valance bands lying lower than the Fermi level are B 2s, B 2p, and Y 4d-B 2p, respectively. The Fermi level EF lies below the valence band maximum at the A point, indicating incomplete filling of valence bands. Then, valence and conduction bands across the Fermi level in Γ–A, A–H, and Γ–K directions of the Brillouin zone imply the presence of metallic bonding and metallic electrical conductivity of YB2. The metallic electrical conductivity contributes to thermal conductivity, leading to higher thermal conductivity, which is of vital importance for UHTCs.

Figure 4.5. Band structure of TMB2: (a) YB2, (b) ZrB2, (c) HfB2, (d) NbB2, and (e) TaB2.

Figure 4.5b shows the band structure of ZrB2. Compared to the band structure of YB2, the Fermi level lies about 2 eV higher than in YB2. The valence and conduction bands cross the Fermi level in the Γ–A and A–H directions of the Brillouin zone, but the valence band in the Γ–K direction is completely filled. Metallic bonding also contribute to the bonding in ZrB2, and the electrical conductivity in ZrB2 is also metallic.

The band structure of HfB2 is similar to that of ZrB2 as is shown in Figure 4.5c, probably due to the fact that Hf has the same number of valence electrons as Zr. However, the Fermi level in HfB2 is higher than in ZrB2 and touches the bottom of conduction bands at the A point and in the Γ–K direction. Valence and conduction bands also cross the Fermi level in the Γ–A and A–H directions of the Brillouin zone. Since the Fermi level is at the minimum of conduction bands at A point and the conduction bands at A point are degenerated, the electron transfer from valence to conduction bands across the Fermi level in Γ–A and A–H directions might be easier, implying better metallic electrical conductivity of HfB2.

In the band structure of NbB2 (Fig. 4.5d), the Fermi level lies above the conduction band minimum at the A point, indicating saturation of valence electrons. Three conduction bands are across the Fermi level in the Γ–A and A–H directions, and two conduction bands cross the Γ–K direction so that the contribution from metallic bonding is higher than that in ZrB2 and HfB2. The band structure of TaB2 is very similar to that of NbB2, as is shown in Figure 4.5e. The only difference is that the Fermi level in TaB2 lies slightly higher than in NbB2. There are also three conduction bands across the Fermi level in the Γ–A and A–H directions and two conduction bands across the Γ–K direction.

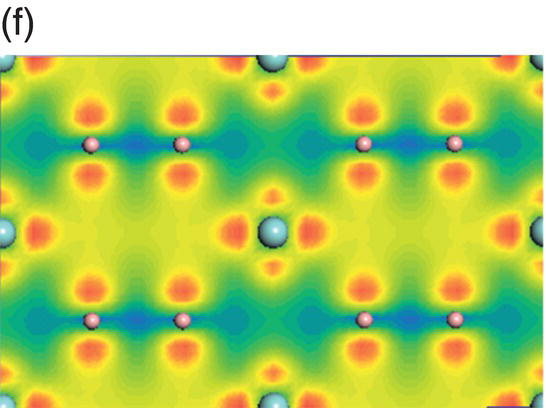

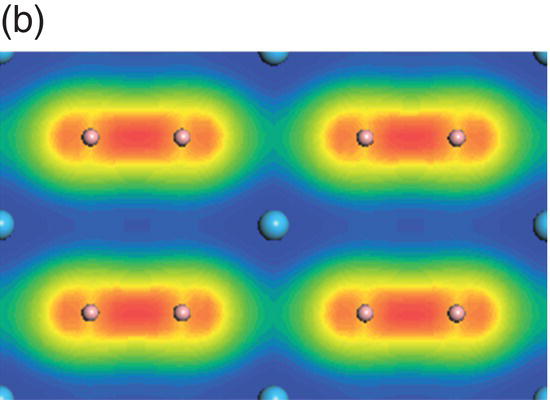

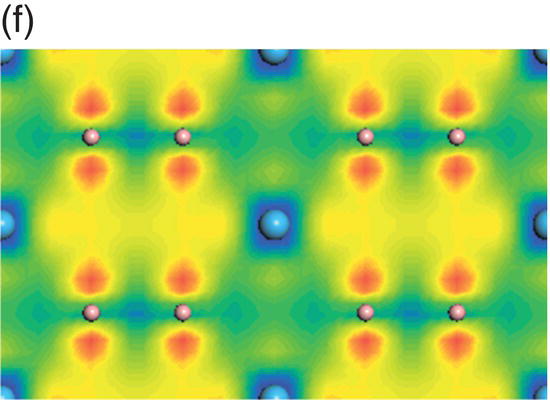

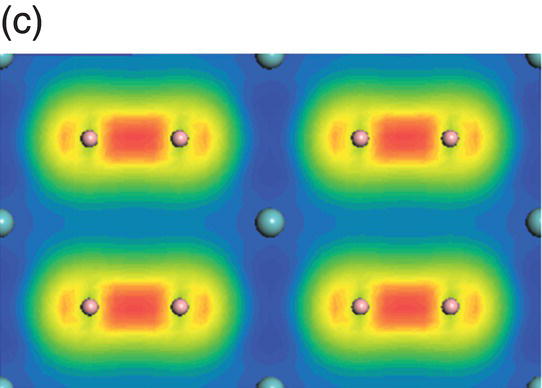

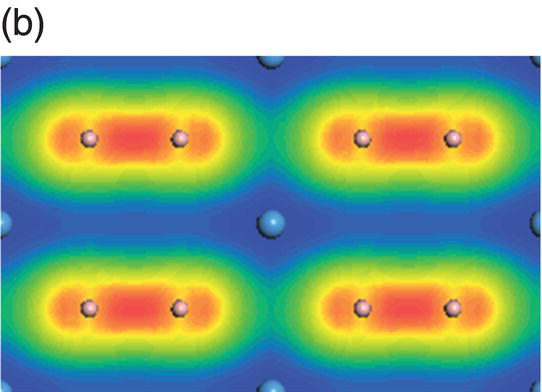

Details of atomic bonding characteristics of TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta) can be seen from the total density of states (TDOS) and projected density of states, as well as the decomposed distribution of charge density from different covalent bonding peaks in the TDOS. Figure 4.6a shows the total and projected electronic DOS of YB2. Two features are obvious in the DOS of YB2: one is a peak at the Fermi level, and the other is the obvious B sp2 hybridization. The presence of the peak at the Fermi level indicates that YB2 is not stable. Strong hybridization between the B-2s and B-2p orbitals is evident because the B 2s orbitals are extended and overlapped in a large energy range with B 2p orbitals. The overlapping of hybridized B sp2–B sp2 orbitals ranges from −10.6 to −7.1 eV below the Fermi level, as can be seen from the distribution of charge density on (11 20) plane of YB2 (Fig. 4.6b). The peaks located from −6.6 to −2.0 eV are mainly from overlapping B sp2–B sp2 orbitals and with some from B 2pz–B 2pz orbitals, as shown in Figure 4.6c. The charge density coming from states in the energy range between −4.3 and 0.44 eV is shown in Figure 4.6d, which is mainly from the overlapping of B 2pz–B 2pz orbitals with some contribution from the overlapping of B sp2–B sp2 orbitals. The states from −2.3 to 0.44 eV are dominated by B 2pz–B 2pz and Y-4d(t2g)–B 2p interactions, as shown in Figure 4.6e. In the energy range from −0.99 to 2.6 eV, the charge density shows d(eg) symmetry at the Y site and 2p-like orbitals at B site, as shown in Figure 4.6f. Thus, the states near the Fermi level are dominated by the Y–Y dd interactions and B–B pp interactions.

Figure 4.6. (a) Total and projected electronic density of states of YB2, and decomposed charge density on (11 20) plane in the energy range from −10.6 to −7.1 eV (b), from −6.6 to −2.0 eV (c), from −4.3 to 0.45 eV (d), from −2.3 to 0.45 eV (e), and from −0.99 to 2.0 eV (f).

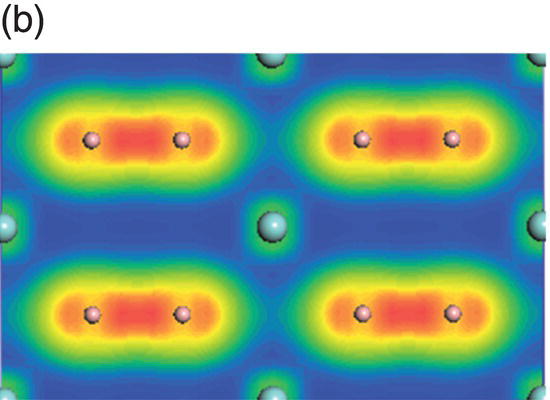

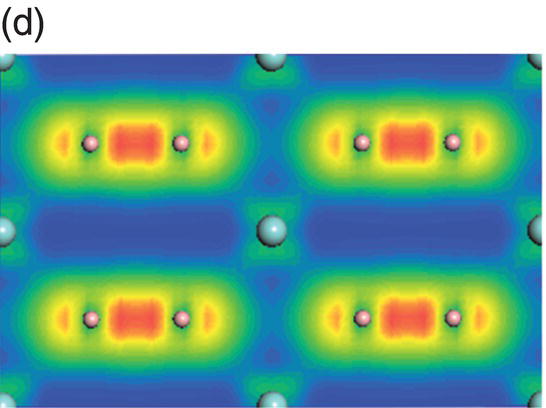

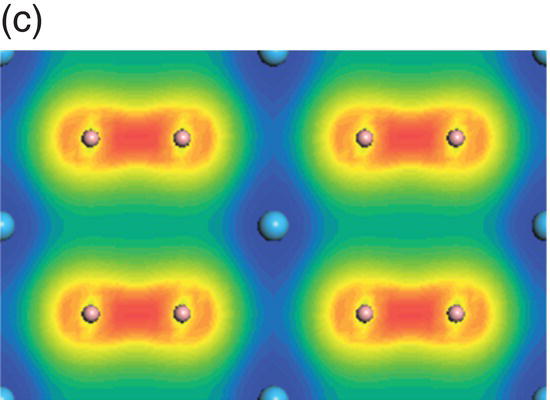

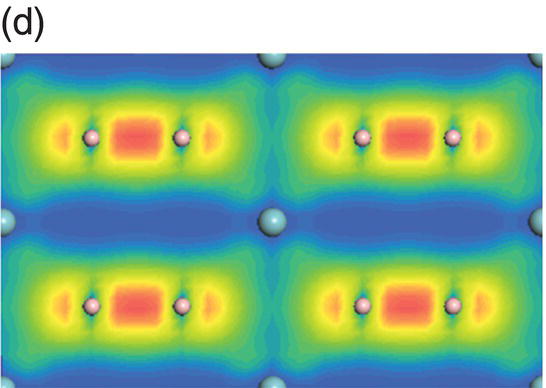

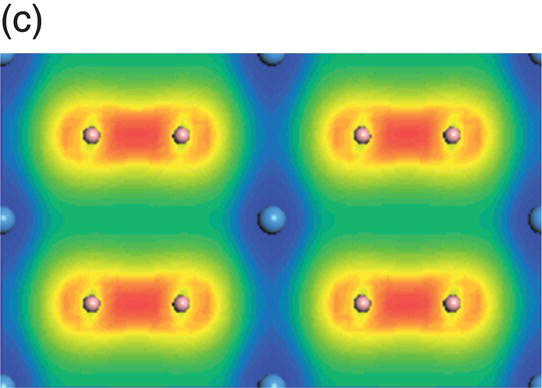

Figure 4.7a shows the total and projected electronic DOS of ZrB2. Besides strong hybridization between the B-2s and B-2p orbitals, the presence of a pseudogap is also obvious. The creation of the pseudogap is, on the one hand, ionic in origin because of charge transfer from Zr to B and, on the other hand, hybridization effects in ZrB2. The states, which are located between −12.7 and −7.8 eV below the Fermi level, come mainly from hybridization of B sp2–B sp2 orbitals, as shown from the distribution of charge density in Figure 4.7b. And those at adjacent higher energy levels from −8.7 to −3.1 eV below the Fermi level are mainly from hybridization of the B sp2–B sp2 orbitals and some from B 2pz–B 2pz orbitals (Fig. 4.7c). In the energy range from −6.8 to −1.1 eV, charge density on the Zr site has t2g symmetry, and B–B bonds have B sp2–B sp2 and B 2pz–B 2pz character (Fig. 4.7d). The peaks located between −4.1 and −1.1 eV are dominated by Zr d(t2g)–B 2pz and B 2pz–B 2pz orbitals (Fig. 4.7e). The charge density in the range extending from −2.7 to 0.6 eV exhibits Zr 4d(eg)–B 2p hybridizations with high accumulation in the x-axis (Fig. 4.7f). Charge density in energy range from −0.03 to 4.0 eV shows eg symmetry on Zr sites and 2pz like orbitals on B sites (Fig. 4.7g). That is, states near the Fermi level are dominated by Zr–Zr dd interactions and B–B pp interactions.

Figure 4.7. (a) Total and projected electronic density of states of ZrB2, and decomposed charge density on (11 20) plane in the energy range from −12.7 to −7.8 eV (b), from −8.7 to −3.1 eV (c), from −6.8 to −1.1 eV (d), from −4.1 to −1.1 eV (e), and from −2.7 to 0.6 eV (f), and from −0.03 to 4.0 eV (g).

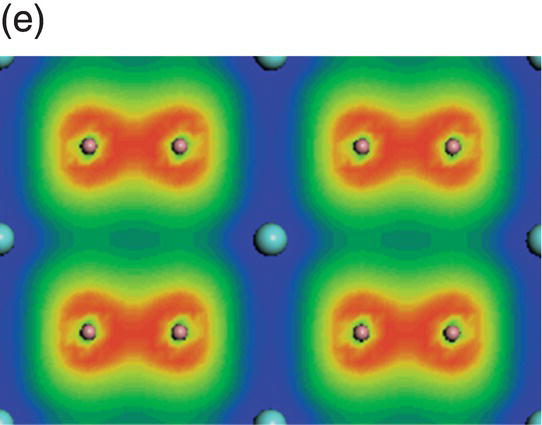

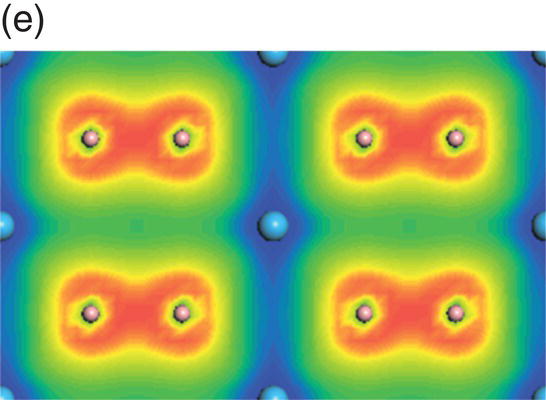

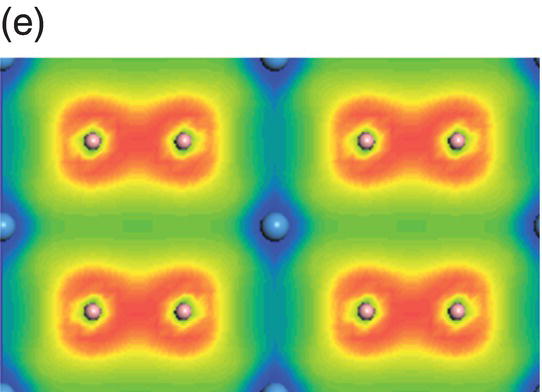

The total and projected electronic DOS for HfB2 are similar to ZrB2 as shown in Figure 4.8a. The energy level of bonding states shifts downward, which indicates enhanced chemical bonding in HfB2. The peaks located at −13.7 to −9.5 eV below the Fermi level are due to overlapping of hybridized B sp2–B sp2 orbitals, as shown in charge density distribution in Figure 4.8b. States between −9.4 and −4.1 eV are dominated by B sp2–B sp2 orbitals and some from B 2pz–B 2pz orbitals, as shown in the charge density distribution in Figure 4.8c. The contribution of B 2pz–B 2pz interactions increases in states in the energy range of −7.1 to −1.4 eV (Fig. 4.8d). Peaks located between −4.8 and −1.4 eV are dominated by Hf d(t2g)–B 2pz B and 2pz–B 2pz orbitals (Fig. 4.8e). The charge density in the range extending from −3.4 to 0.17 eV exhibits Hf 5d(eg)–B 2p interactions with high accumulation in the x-axis (Fig. 4.8f). The charge density in energy range from −0.07 to 4.2 eV shows eg symmetry on Hf site and 2pz like orbitals on the B site (Fig. 4.8g) so that the states near the Fermi level are dominated by the Hf–Hf dd interactions and also B–B pp interactions.

Figure 4.8. (a) Total and projected electronic density of states of HfB2, and decomposed charge density on (11 20) plane in the energy range from −13.7 to −9.5 eV (b), from −9.4 to −4.1 eV (c), from −7.7 to −1.4 eV (d), from −4.8 to −1.4 eV (e), from −3.4 to 1.7 eV (f), and from −0.07 to 4.2 eV (g).

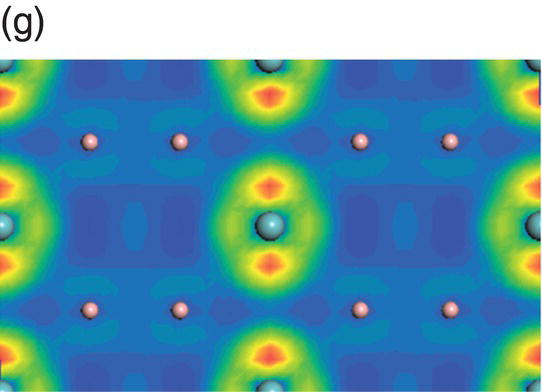

The energy level of bonding states further shifts downward for the DOS of NbB2 as shown in Figure 4.9a. The overlapping of hybridized B sp2–B sp2 orbitals ranges from −14.1 to −10.0 eV below the Fermi level, as is shown in Figure 4.9b. The peaks located from −9.8 to −4.7 eV are mainly from the overlapping of B sp2–B sp2 and some from B 2pz–B 2pz orbitals (Fig. 4.9c). In the energy range from −7.7 to −2.4 eV, the contribution from B 2pz–B 2pz interactions increases, and Nb-4d(t2g)–B 2pz hybridization can also be seen (Fig. 4.9d). The states from −5.5 to −2.4 eV are dominated by B 2pz–B 2pz and Nb-4d(t2g)–B 2pz interactions (Fig. 4.9e) and those from −4.4 to −1.2 eV are dominated by Nb-4d(eg)–B 2pz interactions with high accumulation in the x-axis (Fig. 4.9f). The charge density in the energy range from −1.6 to 1.9 eV shows eg symmetry on the Nb site and pz-like orbitals on the B site (Fig. 4.9g). The charge density in the energy range from −0.7 to 3.5 eV shows eg symmetry on the Nb site and sp2-like orbitals on the B site (Fig. 4.9h), while the charge density in the energy range from −0.6 to 3.8 eV shows eg + t2g symmetry on the Nb site and sp2-like orbitals on the B site (Fig. 4.9i). Shifts of B–B and Nd–B hybridizations to lower energy ranges indicate that B–B and Nb–B bonds in NbB2 are stronger than other diborides, which is supported by the shorter B–B and Nb–B bond lengths as are given in Table 4.1. The enhanced chemical bonding in NbB2 is due to the presence of one more valence electron in Nb and the increased valence electron concentration in NbB2. States at the Fermi level are mainly from Nb-4d states and also from B-2p states, indicating their contribution to metallic conductivity.

Figure 4.9. (a) Total and projected electronic density of states of NbB2, and decomposed charge density on (11 20) plane in the energy range from −14.1 to −10.0 eV (b), from −9.8 to −4.7 eV (c), from −7.7 to −2.4 eV (d), from −5.5 to −2.4 eV (e), from −4.4 to −1.2 eV (f), from −1.6 to 1.9 eV (g), from −0.7 to 3.5 eV (h), and from −0.6 to 3.8 eV (i).

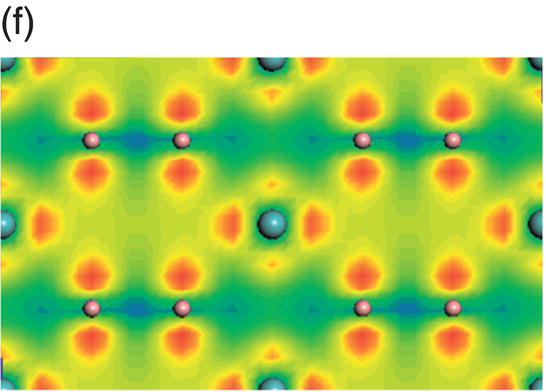

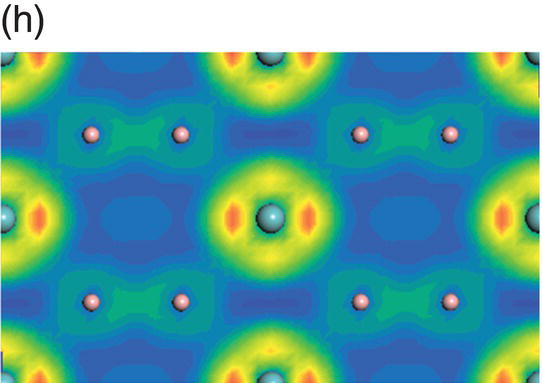

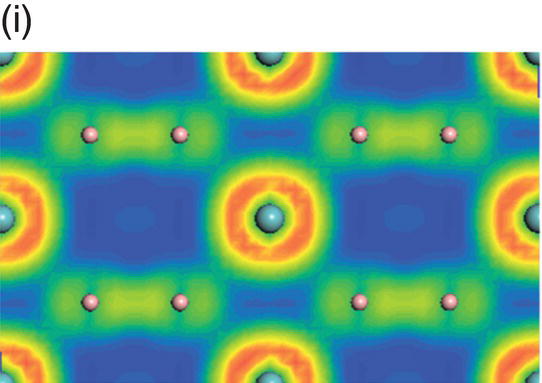

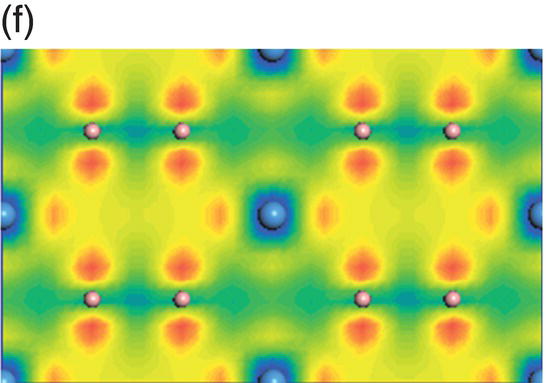

Figure 4.10a shows the total and projected electronic DOS of TaB2. Compared to NbB2, the energy level of bonding states in TaB2 further shifts downward. The overlapping of hybridized B sp2–B sp2 orbitals ranges from −14.9 to −10.7 eV below the Fermi level, which is shown in Figure 4.10b. The peaks located from −10.5 to −5.3 eV are mainly from overlapping of B sp2–B sp2 and some B 2pz–B 2pz orbitals, as shown in Figure 4.10c. The contribution from B 2pz–B 2pz interactions increases in energy range from −8.3 to −2.5 eV as shown in Figure 4.10d and Ta-5d(t2g)–B 2pz interactions can also be seen in this energy range. The states from −6.1 to −2.5 eV are dominated by B 2pz–B 2pz and Ta-5d(t2g)–B 2pz interactions (Fig. 4.10e) and those from −4.8 to −1.3 eV are dominated by Ta-5d(eg)–B 2pz interactions (Fig. 4.10f). The charge density in the energy range from −1.7 to 2.1 eV shows eg symmetry at the Ta site and p-like orbitals at the B site (Fig. 4.10g). The charge density in the energy range from −0.8 to 3.7 eV shows eg symmetry at the Ta site and p+sp2-like orbitals at the B site (Fig. 4.10h). The charge density in the energy range from −0.6 to 4.0 eV shows eg + t2g symmetry at the Ta site and p + sp2-like orbitals at the B site (Fig. 4.10i). The states at the Fermi level are mainly from Ta-5d states and also from B-2p states, indicating their contribution to metallic conductivity.

Figure 4.10. (a) Total and projected electronic density of states of TaB2, and decomposed charge density on (11 20) plane in the energy range from −14.9 to −10.7 eV (b), from −10.5 to −5.3 eV (c), from −8.3 to −2.5 eV (d), from −6.1 to −2.5 eV (e), from −4.8 to −1.3 eV (f), from −1.7 to 2.1 eV (g), from −0.8 to 3.7 eV (h), and from −0.6 to 4.0 eV (i).

The different responses of B–B and TM–B bonds to hydrostatic pressure in TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta) can be understood from atomistic bonding analysis. The TM–B hybridizations in ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 are dominated by TM d(eg)–B 2pz interactions, while the Y–B hybridization is dominated by d (t2g)–B 2pz interactions. As a result, the lattice constant a is stiffer in ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 than for YB2. Another reason is that the Y–B pd bond in YB2 is partially filled so that it is not as stiff as ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2.

4.3.3 Elastic Properties

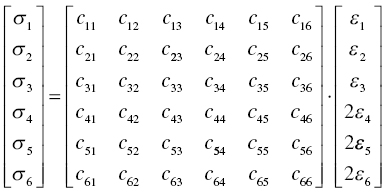

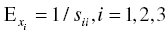

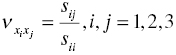

In the last two sections, anisotropic chemical bonding nature has been revealed. Anisotropic chemical bonding can be reflected by an anisotropic Young's modulus [7, 26]. To evaluate the effect of anisotropic chemical bonding on elastic stiffness, second-order elastic constants of single crystals and elastic stiffnesses of polycrystalline TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta) were calculated. The second-order elastic constants were calculated using the following relations:

For hexagonal crystals, only five of the constants are independent, c11, c12, c13, c33, and c44. The anisotropic Young's modulus was calculated from the compliance matrix using Equation (4.2).

Poisson's ratios in different directions were calculated using Equation (4.3).

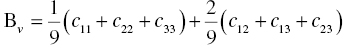

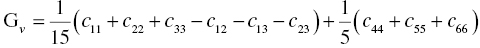

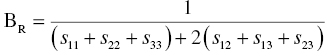

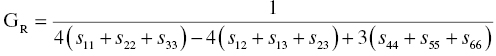

The polycrystalline bulk modulus B, shear modulus G, and Young's modulus E can be estimated from the single-crystal elastic constants, cij, according to the Voigt, Reuss, and Hill approximations [23–25]. According to the Voigt approximation [23], the bulk and shear moduli are expressed as follows:

According to the Reuss approximation [24], the bulk and shear moduli are expressed by

The Voigt and Reuss approximations represent the upper and lower limits of the true polycrystalline modulus. Hill proposed the arithmetic mean values of the Voigt's and Reuss's moduli expressed by [25]

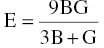

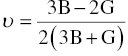

The Young's modulus E and Poisson's ratio ν can be calculated using Hill's bulk modulus B and shear modulus G using the following equations [27]:

Table 4.2 lists the second-order elastic constants cij, and bulk modulus B, shear modulus G, Poisson's ratio v of TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta). The computed elastic constants for ZrB2 and HfB2 are close to those calculated by Lawson et al. [12] and experimental values for ZrB2 [28], demonstrating the reliability of the computed data. Analysis of the data in Table 4.2 shows that the elastic constants are consistent with bonding. For example, the elastic constants c11 and c33, which represent stiffness against principal strains, are anisotropic, that is, c11 is much higher than c33. As a result, the Young's moduli are also anisotropic, that is, the Young's moduli along the x and y directions Ex and Ey are higher than in z direction Ez, corresponding to stronger chemical bonding in the basal plane than in the c direction in the crystal structures of TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta). As the number of valence electrons increases from 3 for Y to 4 for Zr and Hf and then to 5 for Nb and Ta, c11, which represents the stiffness against principal strains in [100] direction, increases from 361 GPa for YB2 to 540 GPa for ZrB2 and 577 GPa for HfB2, and then to 599 GPa for NbB2 and 592 GPa for TaB2, which is consistent with the compressibility of the lattice constant a. The elastic constant c33, which represents the stiffness against principal strains in [001] direction, however, increases from 316 GPa for YB2 to 431 GPa for ZrB2, reaches a maximum value of 448 GPa for HfB2, and then decreases to 437 GPa for NbB2 and 426 GPa for TaB2. The initial increase in c33 is due to enhanced TM d–B p bonding (TM = Y, Zr, Hf), when the number of valence electrons further increases to 5, the additional electron contributing to TM–dd interactions. Similar changes have been observed for c44, which represents shear deformation resistance in (010) or (100) plane in [001] direction. Table 4.2 shows that c44 increases from 160 GPa for YB2 to 250 GPa for ZrB2, then to a maximum value of 253 GPa for HfB2, and after that decreases to 219 GPa for NbB2, and to 189 GPa for TaB2. The value of c44 is closely related to the TM d–B p bonding. The initial increase in c44 is due to the change from partially filled pd bonding states in YB2 to completely filled pd bonding states in ZrB2 and HfB2. Likewise, the decrease in c44 for NbB2 and TaB2 is due to the saturation of pd bonding states and the additional electrons in TM (TM = Nb, Ta) dd orbitals with t2g and eg symmetry near the Fermi level. Similar phenomena have been observed in binary and ternary carbides [32–34] that the enhanced transition metal dd bonding has a negative effect on shear resistance c44. The bulk moduli of polycrystalline TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta) show similar trends. The bulk modulus B, which reflects the resistance to volume change, increases continuously when the number of valence electrons increases from 3 for Y, 4 for Zr and Hf, and 5 for Nb and Ta. The shear modulus G, however, increases from 145 GPa for YB2 to a maximum value of 228 GPa for ZrB2 and 230 GPa for HfB2, and then decreases to 209 GPa for NbB2 and 189 GPa for TaB2. As in transition metal carbides [32–34], the enhancement of both TM d–B p and TM dd bonding is beneficial to bulk modulus B; however, the enhanced TM dd bonding has a negative effect on shear modulus G [34].

Table 4.2. Second-order elastic constants (cij) and bulk modulus B, Young's modulus E, shear modulus G of TMB2 (TM = Y, Zr, Hf, Nb, and Ta)

| Second-order elastic constants | |||||

| cij | YB2 | ZrB2 | HfB2 | NbB2 | TaB2 |

| c11 (GPa) | 361 | 540 | 577 | 599 | 592 |

| c33 (GPa) | 316 | 431 | 448 | 437 | 426 |

| c44 (GPa) | 160 | 250 | 253 | 219 | 189 |

| c12 (GPa) | 65 | 56 | 95 | 107 | 140 |

| c13 (GPa) | 92 | 114 | 129 | 185 | 194 |

| Ex = Ey (GPa) | 329 | 509 | 534 | 520 | 498 |

| Ez (GPa) | 276 | 387 | 398 | 340 | 323 |

| νxy = νyx | 0.116 | 0.051 | 0.107 | 0.055 | 0.102 |

| νxz = νyz | 0.257 | 0.252 | 0.260 | 0.400 | 0.408 |

| νzx = νzy | 0.216 | 0.191 | 0.193 | 0.262 | 0.265 |

| Elastic properties of polycrystalline materials | |||||

| B (GPa) | 171 | 231 | 256 | 287 | 294 |

| G (GPa) | 145 | 228 | 230 | 209 | 189 |

| E (GPa) | 339 | 514 | 531 | 505 | 466 |

| ν | 0.169 | 0.129 | 0.154 | 0.207 | 0.235 |

| S = 0.75 G/B | 0.636 | 0.740 | 0.674 | 0.546 | 0.482 |

The relatively high bulk modulus B, but low shear modulus G, indicates that NbB2 and TaB2 are potentially damage-tolerant ceramics. In Table 4.2, the solidity index S = 0.75G/B of TMB2 (TM = Zr, Hf, Nb, Ta, and Y), which can be used as a criterion to distinguish brittle and ductile materials [29]. Low–solidity index materials are more damage tolerant. For example, the solidity indices for damage-tolerant layered ternary carbides (i.e., MAX phases) are less than 0.5 [30]. Among the TMB2 compounds, TaB2 has the lowest solidity index (0.482). Therefore, it is expected to be the most damage tolerant among the TMB2 investigated in the present work. The other possible damage-tolerant material is NbB2 because it also has a low solidity index (0.546). The predicted intrinsic brittleness increases in the order TaB2 < NbB2 < YB2 < HfB2 < ZrB2.

The Young's moduli of TMB2 are strongly related to thermal shock resistance. Table 4.2 shows that the Young's moduli follows the trend HfB2 > ZrB2 > NbB2 > TaB2 > YB2. Since YB2 has the lowest Young's modulus among the investigated TMB2, it is expected to have the best thermal shock resistance. TaB2 has both low solidity index and Young's modulus, it is predicted to have better thermal shock resistance and damage tolerance than HfB2 and ZrB2.

4.4 Conclusion Remarks

The chemical bonding and anisotropic elastic properties of several TMB2 including YB2, ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 were studied. The response of lattice constants and bond lengths to hydrostatic pressure was examined as well as electronic structure, second-order elastic constants of single crystals, and elastic moduli of bulk polycrystalline materials. Lattice constants, bond lengths, and compressibility decrease when the number of valence electrons increases from 3 for Y to 4 for Zr and Hf, and then to 5 for Nb and Ta. The stiffness along the a direction is higher than that along c direction, corresponding to the stronger covalent bonding in the basal plane. DOS and band structure analysis reveal that B–B bonding is strong covalent, TM–B bonding is ionic–covalent, and TM–TM bonding is metallic. The mechanical properties are anisotropic due to the anisotropic chemical bonding nature. The Young's moduli in the x and y directions are much higher than that in the z direction. The bulk modulus increases when TM changes from Y, to Zr and Hf, and then to Nb and Ta. The shear modulus, however, increases from 145 GPa for YB2 to 228 GPa for ZrB2 , reaches a maximum value of 230 GPa for HfB2, and decreases to 209 GPa for NbB2 and 189 GPa for TaB2. The continuous increase in bulk modulus B is due to enhancement of TM d–B p and TM dd bonding, which is beneficial to the enhanced bulk modulus. The initial increase and then decrease in shear modulus G can be explained by enhanced TM d–B p bonding, which has a positive effect on shear resistance, while excessive occupation of TM dd bonding has a negative effect on shear modulus G. The Young's moduli of TMB2 are in the order of HfB2 > ZB2 > NbB2 > TaB2 > YB2. YB2 is predicted to have the best thermal shock resistance since it has the lowest Young's modulus. The brittleness, based on the calculated solidity index S = 0.75G/B, is estimated in the order TaB2 < NbB2 < YB2 < HfB2 < ZrB2. Because TaB2 has both low solidity index and Young's modulus, it is predicted to have better thermal shock resistance and damage tolerance.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Outstanding Young Scientist Foundation for Y. C. Zhou under Grant No. 59925208, and the Natural Sciences Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 50672102, 50832008, 51032006, and 91226202.

References

- 1. Van Wie DM, Drewry DG Jr, King DE, Hudson CM. The hypersonic environment: required operating conditions and design challenges. J Mater Sci 2004;39 (19):5915–5924.

- 2. Opeka MM, Talmy IG, Zaykoski JA. Oxidation-based materials selection for 2000oC+ hypersonic aerosurfaces: theoretical considerations and historical experience. J Mater Sci 2004;39 (19):5887–5904.

- 3. Jackson TA, Eklund DR, Fink AJ. High speed propulsion: performance advantage of advanced materials. J Mater Sci 2004;39 (19):5905–5913.

- 4. Wuchina E, Opeka M, Causey S, Buesking K, Spain J, Cull A, Routbort J, Guitierrez-Mora F. Designing for Ultrahigh-temperature applications: the mechanical and thermal properties of HfB2, HfCx, and α-Hf(N). J Mater Sci 2004;39 (19):5939–5949.

- 5. Corral EL, Loehman RE. Ultra-high temperature ceramic coatings for oxidation protection of carbon-carbon composites. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (5):1495–1502.

- 6. Blum YD, Marschall J, Hui D, Young S. Thick protective UHTC coatings for SiC based structures: process establishment. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (5):1453–1460.

- 7. Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Talmy IG, Zaykoski JA. Refractory diborides of zirconium and hafnium. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (5):1347–1364.

- 8. Sarin P, Driemeyer PE, Haggerty RP, Kim DK, Bell JL, Apostolov ZD, Kriven WM. In situ studies of oxidation of ZrB2 and ZrB2-SiC composites at high temperatures. J Eur Ceram Soc 2010;30 (11):2375–2386.

- 9. Gangireddy S, Karlsdottir SN, Norton SJ, Tucker JC, Halloran JW. In situ microscopy observation of liquid flow, zirconia growth, and CO bubble formation during high temperature oxidation of zirconium diboride-silicon carbide. J Eur Ceram Soc 2010;30 (11):2365–2374.

- 10. White A. The materials genome initiative: one year on. MRS Bull 2012;37 (8):715–716.

- 11. Vajeeston P, Ravindran P, Ravi C, Asokamani R. Electronic structure, bonding, and ground-state properties of AlB2-type transition-metal diborides. Phys Rev B 2001;63:045115.

- 12. Lawson JW Jr, Bauschlicher CW, Daw MS. Ab initio computations of electronic, mechanical, and thermal properties of ZrB2 and HfB2. J Am Ceram Soc 2011;94 (10):3494–3499.

- 13. Shein IR, Ivanovski AL. Elastic properties of mono-and polycrystalline hexagonal AlB2 like diborides of s, p and d metals from first-principles calculations. J Phys Condens Matter 2008;20:415218.

- 14. Kresse G, Furthmller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Comput Mater Sci 1996;6:15–50.

- 15. Gonze X, Rignanese GM, Verstraete M, Beuken JM, Bottin F, Boulanger P, Bruneval F, Caliste D, Caracas R, Cote M, Deutsch T, Genovese L, Ghosez P, Guantomassi M, Goedecker S, Hamann DR, Hermet P, Jollet F, Jomard G, Lerous S, Mancini M, Mazevet S, Oliveira MJT, Onida G, Pouillon Y, Rangel T, Rignanese GM, Sangalli D, Shaltaf R, Torrent M, Verstraete MJ, Zerah G, Zwanzier JW. ABINI: first-principles approach of materials and nanosystem properties. Comput Phys Commun 2009;180:2582–2615.

- 16. Segall MD, Lindan PLD, Probert MJ, Pickard CJ, Hasnip PJ, Clarc SJ, Payne MC. First-principles simulation: ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J Phys Condens Mater 2002;14:2717–2744.

- 17. Vanderbilt D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotential in a generalized eignevalue formalism. Phys Rev B 1990;41:7892–7895.

- 18. Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett 1996;77:3865–3868.

- 19. Pack JD, Monkhorst HJ. Special points for brillouin-zone integrations-A reply. Phys Rev B 1977;16:1748–1749.

- 20. Pfrommer BG, Côté M, Louie SG, Cohen ML. Relaxation of crystals with the Quasi-Newton method. J Comput Phys 1977;131:233–240.

- 21. Milman V, Warren MC. Elasticity of hexagonal BeO. J Phys Condens Matter 2001;13:241–251.

- 22. Ravindran P, Fast L, Korzhavyi PA, Johansson B, Wills J, Eriksson O. Density functional theory for calculation of elastic properties of orthorhombic crystals: application to TiSi2. J Appl Phys 1998;84:4891–4904.

- 23. Voigt W. Lehrbuch der Kristallohysic. Leipzig: Teubner; 1928.

- 24. Reuss A. Berechnung der Flieβgrenze von Mischkristallen auf Grund der Plastizittsbedingung für Einkristalle. Z Angew Meath Mech 1929;9:49–58.

- 25. Hill R. The elastic behaviour of a crystalline aggregate. Proc Phys Soc A 1952;65:349–354.

- 26. Gilman JJ, Roberts BW. Elastic constants of TiC and TiB2. J Appl Phys 1961;32 (7):1405.

- 27. Green DJ. An Introduction to the Mechanical Properties of Ceramics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. p 20–88.

- 28. Okamoto NL, Kusakari M, Tanaka K, Inui H, Yamaguichi M, Otani S. Temperature dependence of thermal expansion and elastic constants of single crystals of ZrB2 and the suitability of ZrB2 as a substrate for GaN film. J App Phys 2003;93:88–94.

- 29. Gilman JJ. Electronic Basis of the Strength of Materials. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. p 110.

- 30. Wang JY, Zhou YC. Recent progress in theoretical prediction, preparation, and characterization of layered ternary transition-metal carbides. Ann Rev Mater Res 2009;39:10.01–10.29.

- 31. Zhou YC, Sun ZM. The electronic structure and chemical bonding in Ti3GeC2. Mater Chem 2000;10:343–346.

- 32. Wang JY, Zhou YC. Dependence of elastic stiffness on electronic band structure of nanolaminate M2AlC (M=Ti, V, Nb, and Cr) ceramics. Phys Rev B 2001;69:214111.

- 33. Wang JY, Zhou YC. Ab initio elastic stiffness of nano-laminate (MxM'2-x)AlC (M and M'=Ti, V and Cr) solid solutions. J Phys Condens Matter 2004;16:2819–2827.

- 34. Jhi SH, Ihm J, Louie SG, Cohen ML. Electronic mechanism of hardness enhancement in transition-metal carbonitrides. Nature 1999;399:132–134.