10

Deformation and Hardness of UHTCs as a Function of Temperature

J. Wang and L. J. Vandeperre

Centre for Advanced Structural Ceramics, Department of Materials, Imperial College London, London, UK

10.1 Introduction

According to Fahrenholtz and coworkers, ultra-high-temperature ceramics (UHTCs) are the materials with a melting point above 3000°C [1]. The transition metal carbides, nitrides, and borides belong to the group of UHTCs and will be the main focus of the discussion.

When crystalline materials are loaded with small forces, resistance to deformation stems from bond stretching and a reversible return to the original state when the load is released—the elastic response. As the load increases, irreversible deformation mechanisms are eventually activated in which matter is displaced permanently by dislocations or diffusion to relieve the applied stress by deformation. Alternatively, if the required stresses for such mechanisms are very high, crack propagation can lead to failure of the material. All these aspects of the mechanical behavior of crystalline materials are, to some extent, temperature dependent, and this dependence will be discussed. Since the elastic response is an important precursor to all other mechanisms and often the stresses or strains needed scale with the elastic properties, the chapter will start by exploring the elastic properties. Following this, the discussion will turn to hardness measurements and, specifically, the use of hardness measurements as a convenient experiment to investigate the resistance to plastic deformation. As the temperature increases, deformation becomes increasingly easy as a multitude of creep mechanisms aid in the progression of deformation. These will be discussed as well. Finally, failure by fracture will not be discussed much in this chapter as it has already been discussed in Chapter 9. However, the reader will be reminded that fracture is a competing mechanism to deformation, that is, deformation will only occur to a large extent if fracture can be avoided.

10.2 Elastic Properties

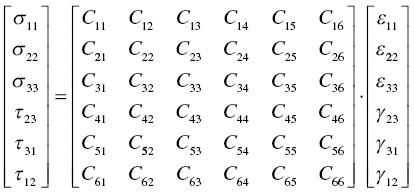

Bulk ceramics contain many grains in random orientations and can, therefore, be considered isotropic in their response to elastic loading. However, since this isotropic response is a weighted average of the anisotropic response of the single-crystal grains from which the body is made, it remains instructive to consider the elastic response of a single crystal. The carbides of the early transition metals with melting point above 3000°C (ZrC, HfC, TaC, and NbC) are all cubic with the rock salt structure (space group  ). This means that the contracted relationship between stresses and strains

). This means that the contracted relationship between stresses and strains

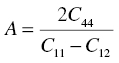

which describes the elastic response of single crystals, only contains 3 independent elastic constants—C11 (=C22 = C33), C12 (=C13 = C21 = C23 = C31 = C32), and C44 (=C55 = C66)—and all other constants are zero. Zeener defined the anisotropy number, A, of cubic crystals as [2]

Calculation of the shear modulus in all possible orientations using the transformations given in Ref. [3] shows that for cubic crystals this is the ratio of the extremes of the shear moduli and therefore a good measure for the anisotropy in the elastic response.

Experimental values for the elastic constants are reported in bold in Table 10.1 alongside values reported from first-principles and other theoretical calculations. The experimental values show that A is in between 0.71 and 0.95. This means that shear across the {100} planes in 〈010〉 directions is easier than shear across the {111} planes in any direction and that pulling along <111> directions has the lowest Young's modulus for any direction in the crystal, while pulling in <100> directions gives rise to the highest Young's modulus. However, the variations are limited to 40% between maximum and minimum values.

Table 10.1. Elastic constants (C11, C12, and C44) and elastic properties of UHTC carbides with the cubic rock salt structure (NaCl, Fm-3 m), with K as the bulk modulus and Eavg the average Young's modulus over all orientations

| Substance | C11 | C12 |  |

|

K | A | Eavg | Method | References |

| ZrC | 548 | 87 | 87 | 231 | 241 | 0.377 | 346 | (-) | [4] |

| ZrC | 643 | 74 | 121 | 285 | 264 | 0.425 | 442 | LDA | [4] |

| ZrC | 483 | 109 | 110 | 187 | 234 | 0.558 | 355 | GGA | [5] |

| ZrC | 512 | 95 | 128 | 209 | 234 | 0.614 | 396 | GGA | [4] |

| ZrC | 452 | 92 | 112 | 180 | 212 | 0.622 | 347 | MIPMCv | [4] |

| ZrC | 441 | 60 | 151 | 191 | 187 | 0.793 | 391 | EXP | [6] |

| ZrC | 472 | 99 | 159 | 187 | 223 | 0.853 | 411 | EXP | [5] |

| ZrC | 468 | 100 | 159 | 174 | 233 | 0.864 | 409 | 3BFP | [5] |

| ZrC | 470 | 100 | 160 | 185 | 223 | 0.865 | 411 | EXP | [7] |

| HfC | 454 | 87 | 87 | 184 | 209 | 0.471 | 311 | (-) | [4] |

| HfC | 474 | 88 | 98 | 193 | 217 | 0.508 | 367 | MIPMCv | [4] |

| HfC | 556 | 97 | 143 | 230 | 250 | 0.623 | 436 | LDA | [4] |

| HfC | 548 | 99 | 142 | 225 | 249 | 0.633 | 430 | GGA | [5] |

| HfC | 556 | 105 | 152 | 226 | 255 | 0.674 | 446 | GGA | [4] |

| HfC | 498 | 113 | 179 | 193 | 241 | 0.939 | 443 | 3BFP | [5] |

| HfC | 500 | 114 | 180 | 193 | 243 | 0.933 | 449 | EXP | [5] |

| HfC | 500 | 180 | EXP | [7] | |||||

| TaC | 505 | 91 | 79 | 207 | 229 | 0.382 | 316 | [8] | |

| TaC | 694 | 127 | 127 | 284 | 316 | 0.448 | 467 | (-) | [4] |

| TaC | 486 | 115 | 130 | 186 | 239 | 0.701 | 383 | MIPMCv | [4] |

| TaC | 621 | 155 | 167 | 233 | 311 | 0.716 | 487 | GGA | [8] |

| TaC | 547 | 119 | 159 | 214 | 262 | 0.743 | 448 | 3BFP | [5] |

| TaC | 550 | 150 | 190 | 200 | 283 | 0.950 | 479 | EXP | [7] |

| TaC | 370 | 110 | 153 | 130 | 197 | 1.177 | 341 | GGA | [5] |

| TaC | 595 | 153 | EXP | [8] | |||||

| NbC | 648 | 109 | 109 | 270 | 289 | 0.404 | 420 | (-) | [4] |

| NbC | 593 | 126 | 132 | 234 | 282 | 0.565 | 433 | MIPMCv | [4] |

| NbC | 460 | 159 | 103 | 151 | 259 | 0.684 | 321 | GGA | [5] |

| NbC | 620 | 200 | 150 | 210 | 340 | 0.714 | 453 | EXP | [7] |

| NbC | 617 | 199 | 159 | 209 | 338 | 0.761 | 463 | 3BFP | [5] |

| NbC | 587 | 121 | 220 | 233 | 276 | 0.944 | 534 | LDA | [4] |

| NbC | 627 | 159 | 224 | 234 | 315 | 0.957 | 553 | GGA | [4] |

All values are in GPa except A, which is dimensionless; experimental results are shown in bold.

EXP, experimental; GGA, generalized gradient approximation; LDA, local density approximation; MIPMC, modified interaction potential model with covalency; 3BFP, 3-body force potential.

Theoretical estimates for elastic constants are variable. Clearly, two common simplifying assumptions made to enable the calculation (local density approximation, generalized gradient approximation) tend to overestimate the anisotropy of crystals. Bhardwaj and Singh [4] attribute this to many first-principles calculations ignoring the dipole–dipole and dipole–quadruple interactions. However, modified interaction potential model with covalency overall does not seem to give much better agreement with the experimental values, whereas the three-body force potential does capture the anisotropy of the crystals and seems to give estimates closest to experimental values.

The nitrides, which also have a rock salt structure, appear to be more anisotropic (see Table 10.2), and here, theoretical calculations appear to capture the anisotropy better. Hence, although no experimental information for TaN was found, the theoretically calculated high anisotropy (A = 0.17), which means the maximum shear modulus (384 GPa) is six times larger than the lowest shear modulus (64 GPa), could be true. Such high anisotropy is not very common, but it is of the same order of magnitude as in the alkali metal group (Li, 9.1; Na, 6.8; K, 6.7; Rb, 6.2; and Cs 7.2) [6] and, therefore, well within what has been observed for crystals.

Table 10.2. Elastic constants (C11, C12, and C44) and elastic properties of UHTC nitrides with the cubic rock salt structure (NaCl, Fm-3 m), with K as the bulk modulus and Eavg the average Young's modulus over all orientations

| Substance | C11 | C12 |  |

|

K | A | Eavg | Method | References |

| ZrN | 523 | 111 | 116 | 206 | 248 | 0.563 | 381 | [9] | |

| ZrN | 471 | 88 | 138 | 192 | 216 | 0.721 | 389 | EXP | [10] |

| ZrN | 547 | 150 | 147 | 199 | 282 | 0.741 | 426 | LDA | [10] |

| ZrN | 462 | 141 | 143 | 161 | 248 | 0.891 | 378 | GGA | [10] |

| HfN | 659 | 141 | 102 | 259 | 314 | 0.394 | 407 | LDA | [10] |

| HfN | 561 | 147 | 100 | 207 | 285 | 0.483 | 365 | GGA | [10] |

| HfN | 588 | 113 | 120 | 238 | 271 | 0.505 | 415 | GGA | [9] |

| HfN | 679 | 119 | 150 | 280 | 306 | 0.536 | 498 | EXP | [10] |

| TaN | 848 | 133 | 62 | 358 | 371 | 0.173 | 367 | GGA | [10] |

| TaN | 898 | 131 | 64 | 384 | 387 | 0.166 | 384 | [11] | |

| TaN | 906 | 140 | 64 | 383 | 395 | 0.167 | 385 | LDA | [10] |

All values are in GPa except A, which is dimensionless; experimental results are shown in bold.

EXP, experimental; GGA, generalized gradient approximation; LDA, local density approximation; MIPMC, modified interaction potential model with covalency; 3BFP, 3-body force potential.

The borides are hexagonal crystals (space group P6/mmm). The lower symmetry of hexagonal crystals means that there are five independent elastic constants: C11 (=C22), C12 (=C21), C13 (=C31 = C32 = C23), C33, C44 (=C55). In addition to these independent constants, one other value is different from zero but dependent on the value of others (C66 = (C11 − C12)/2). The anisotropy number, A, can be defined in analogy with the one for cubic crystals by taking the ratio of the maximum to minimum value of the shear modulus, but is not defined directly by the elastic constants. It must therefore be evaluated by calculating G for all possible orientations of shear deformation. As shown in Table 10.3, calculations and experiments for diborides appear to agree quite well that anisotropy is limited (maximum shear modulus 40% higher than the minimum shear modulus), which is similar to what was observed experimentally for carbides. Young's modulus is lowest perpendicular to the basal plane, that is, along the c-axis, and the highest shear modulus is for shear in the c-direction in a plane perpendicular to any of the a-directions.

Table 10.3. Elastic constants and elastic properties of UHTC borides with the hexagonal structure (P6/mmm), with K as the bulk modulus and Eavg the average Young's modulus over all orientations

| Substance | C11 | C12 | C13 | C33 | C44 | K | A | Eavg | Method | References |

| ZrB2 | 568 | 57 | 121 | 436 | 248 | 240 | 1.38 | 495 | EXP | [12] |

| ZrB2 | 553 | 64 | 113 | 419 | 234 | 232 | 1.35 | 476 | GGA | [13] |

| ZrB2 | 563 | 64 | 133 | 446 | 253 | 248 | 1.40 | 496 | GGA | [13] |

| HfB2 | 578 | 71 | 118 | 430 | 228 | 242 | 1.35 | 485 | GGA | [13] |

| HfB2 | 609 | 73 | 135 | 470 | 266 | 263 | 1.36 | 530 | GGA | [13] |

| HfB2 | 583 | 98 | 132 | 456 | 258 | 259 | 1.36 | 508 | GGA | [14] |

| HfB2 | 593 | 100 | 141 | 481 | 262 | 269 | 1.35 | 523 | GGA | [14] |

| TiB2 | 660 | 67 | 99 | 462 | 260 | 252 | 1.33 | 549 | EXP | [15] |

| TiB2 | 671 | 64 | 101 | 473 | 267 | 256 | 1.33 | 561 | EXP | [15] |

| TiB2 | 660 | 48 | 93 | 432 | 260 | 240 | 1.42 | 538 | EXP | [15] |

All values are in GPa except A, which is dimensionless; experimental results are shown in bold.

EXP, experimental; GGA, generalized gradient approximation.

In summary, near room temperature, the elastic properties of the UHTC materials tend to be fairly isotropic. As a rule, UHTCs have a high stiffness with Young's moduli of the diborides (~500–600 GPa) exceeding those of the carbides and nitrides (~300–500 GPa). Theoretical predictions of the elastic properties are currently reasonable and capture the order of magnitude of the stiffness quite well. However, comparison with experiments shows that the predictions tend to overestimate elastic anisotropy in these materials.

While theoretical predictions for the effect of increased pressure on elastic constants and phase stability of UHTCs are available (see, e.g., [4, 14]), no predictions of the variation of the elastic constants with temperature were found. Experimentally, the most complete set of measurements are for ZrB2 for which Okamoto and coworkers measured the variation of all five elastic constants with temperature up to 1400 K [12]. As shown in Figure 10.1a, C11, C33, and C44 decrease noticeably with temperature, while C13 and C12 depend less on temperature. Evaluation of the ratio of maximum to minimum shear modulus as a function of temperature shows that the elastic anisotropy remains constant with temperature.

Figure 10.1. (a) Elastic constants for ZrB2 as a function of temperature as measured by Okamoto et al. [12] and (b) the average Young's modulus, Eavg (filled squares); shear modulus, Gavg (filled triangles); and bulk modulus, K (filled circles), as a function of temperature using the same data. Also shown are the variation of Young's modulus as measured in flexure by Neuman et al. (half-filled diamonds) [16] and Rhodes et al. (open diamonds) [17] and the variation of Young's modulus of ZrB2 as measured from the natural resonance frequency (open squares) [18].

Figure 10.1b illustrates that the average shear modulus, obtained by averaging G for all possible orientations in 5° steps, decreases more strongly with temperature than the bulk modulus, K. Also, the decrease in average Young's modulus calculated from elastic constants agrees with the measured variation of Young's modulus by means of measuring the natural vibration frequency of a bar [18]. Below 1250 K, the data obtained in flexure [16, 17] also agrees with the single-crystal data. However, the latter measurements show a strong decrease for temperatures in excess of 1250 K. This suggests that the lower values are a result of creep influencing the measured slope or other problems. Indeed, such a dramatic decrease in elastic properties far away from any phase transition would be surprising, and the elastic modulus of ZrB2 should really only decrease significantly on approaching its melting point.

This interpretation is confirmed when measurements for other borides and carbides obtained by measuring the natural frequency of vibration [19] are compared with flexural measurements (see Fig. 10.2). Again, a much more dramatic decrease with temperature is found for Young's modulus derived from flexural data than for the data obtained by impulse excitation of a natural vibration frequency. Especially the data for ZrC, which extends beyond 2000 K, indicates only a modest decrease in stiffness up to 2000 K. The slope by which the elastic modulus decreases with temperature divided by the value of Young's modulus at 298 K is reported in Table 10.4 and in all cases is of the order of −0.01% K−1, that is, the elastic properties decay by about 1% every 100 K.

Figure 10.2. Young's modulus versus temperature for a range of UHTCs. Closed symbols are measurements based on vibration, whereas open symbols were obtained from flexural tests. Data from Refs. [18, 20–23].

Table 10.4. Rate of decay of the elastic modulus with temperature

| Substance | 1/E298 K × dE/dT (K−1) |

| ZrB2 | −0.009% |

| TiB2 | −0.004% |

| HfB2 | −0.008% |

| ZrC | −0.012% |

| TaC | −0.015% |

| NbC | −0.014% |

10.3 Hardness

Hardness measurements are often used to characterize mechanical behavior because the experiment is relatively easy and can be conducted on small specimens. Typically, a shape manufactured out of a very deformation-resistant material is pressed into the surface of the sample, and the ratio of the applied load to the size or depth of the (residual) imprint is taken as a measure of the hardness. In this chapter, hardness will be defined as the ratio of applied force, F, to projected area, Apr, of the residual imprint after unloading:

Vickers hardness is the ratio of applied force to pyramidal contact area. Therefore, to convert Vickers hardness values to projected hardness, the Vickers hardness needs to be divided by 0.9272 to account for the fact that the projected area is smaller than the true contact area [24].

While the experiment is easy to conduct, interpretation of hardness values is more difficult. Not only do hardness values depend on the method chosen to measure it, but it is often observed that the hardness is lower if the applied load is increased [25]. Numerous empirical equations and models have been put forward to quantify or explain this size effect [25–31]. Many of these explanations were first put forward in the time when microindenters became popular and enabled the analysis of small indents. At the time, it was assumed that deformation became more difficult when the indentation became smaller and, hence, the hardness obtained from larger indentations should be the true hardness reflecting the plastic properties. However, progress toward instrumentation, allowing even smaller indents (nanoindenters), suggests that these explanations might be incorrect for ceramics—at least at this scale. For example, data for slightly porous ZrB2 and a dense ZrB2 with 20 vol% SiC collected across a wide range of loads in Figure 10.3 shows that hardness at low loads is more or less constant and that the hardness decreases from this constant level as the load is increased. Interestingly, the transition between a constant hardness and a decreasing hardness tends to coincide with the onset of cracking around the indentation. Therefore, the data in Figure 10.3 supports Quinn's [31] suggestion that cracking has at least some role to play in explaining size effects in indentation of ceramics.

Figure 10.3. Hardness of two types of zirconium diboride (100% dense with addition of 20 vol% SiC and 90% dense with no additions) as a function of the size of the applied load. Data from Ref. [32].

Hence, hardness obtained from small indentations (100–200 mN) is a measure for the resistance to plastic deformation, whereas the hardness obtained from larger indents is a complex composite of the resistance to plastic deformation and fracture. The idea that fracture plays a role is not new and has been exploited in methodologies where the toughness of the material is derived from the size of the cracks relative to the size of the indents [33–35].

The data in Figure 10.3 also illustrate that at larger loads, the hardness of porous materials tends to be lower than that of dense materials in keeping with empiric relationships, which predict an exponential decrease of hardness with porosity [36].

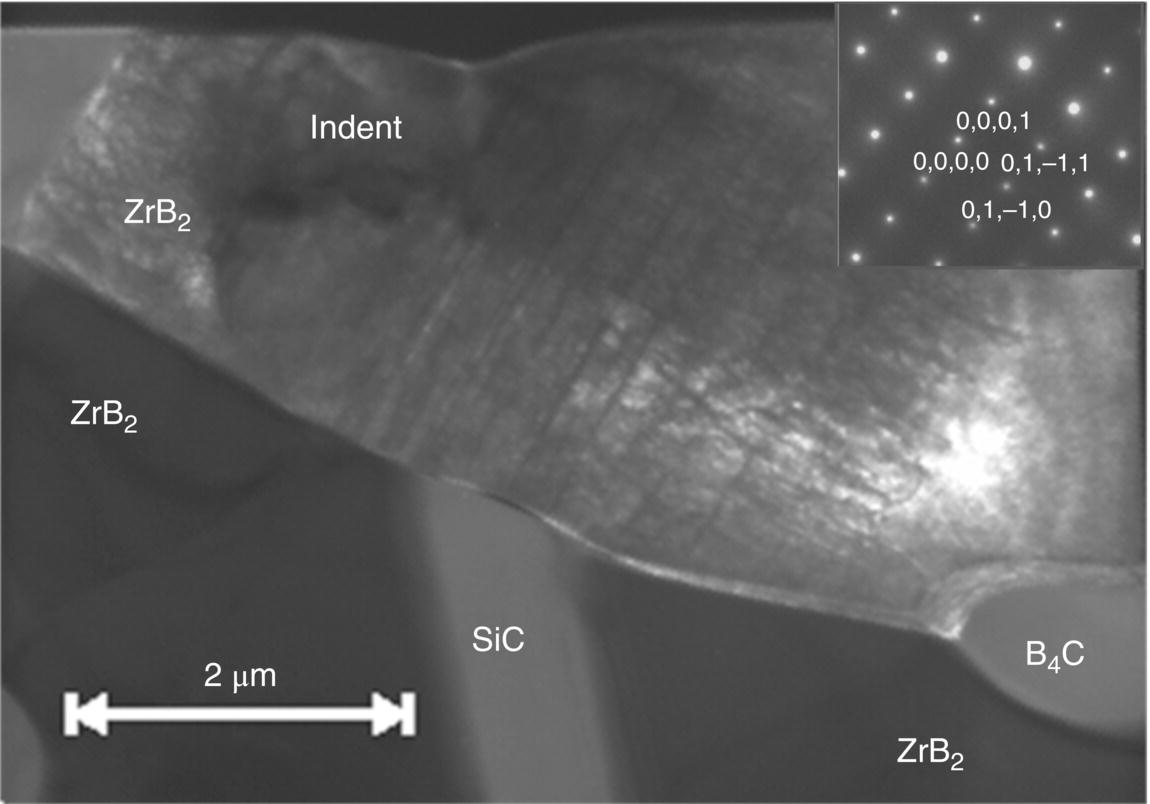

Other microstructural features can play a role in hardness measurements too. Especially relevant is measurement of hardness in the case of ceramics containing several phases such as in ZrB2 with SiC and B4C [32]. For small indents, which are of the same size as the phases in the microstructure, three distinct hardness groupings with hardness values close to the hardness of the different phases can be seen in Figure 10.4, whereas for larger indents, a composite hardness is obtained, which is slightly higher than that of the ZrB2. However, even when an indent is apparently made in a single phase, it is difficult to judge what might be present underneath the indentation. The TEM cross section through an indent in Figure 10.5 shows how the SiC grain appears to have resisted deformation better than the surrounding ZrB2 and looks as if it was being pushed into the ZrB2 grain, which suggests that the hardness measured will have been influenced by the SiC grain present underneath the indent.

Figure 10.4. Hardness as a function of load in a ZrB2 containing SiC and B4C. Data taken from Ref. [32]. Where indents were apparently made in a single phase, they have been grouped accordingly.

Figure 10.5. TEM bright-field micrograph of a cross section through a Berkovich indent in ZrB2 containing SiC. It appears that the SiC has resisted deformation more and has been pushed into the ZrB2 grain above it. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 37. © The American Ceramic Society.

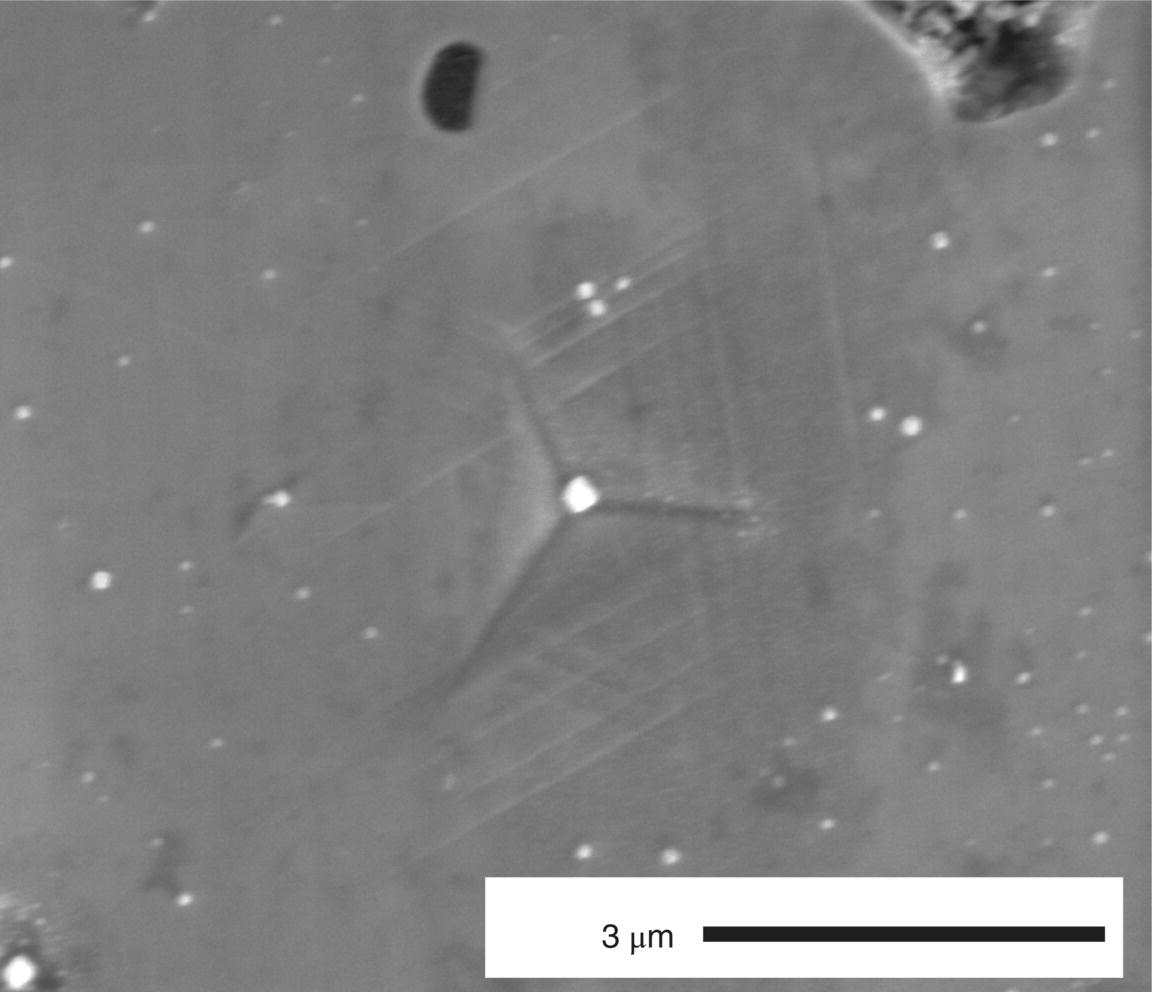

Figure 10.5 also shows, quite clearly, that tremendous dislocation activity occurs underneath the indentation, even at room temperature. Other evidence of dislocation activity is the appearance of slip lines on the surface (see Fig. 10.6). Similar slip lines in ZrB2 have also been reported by Ghosh et al. [38, 39]. This confirms that indentation can be used for studies of dislocation plasticity in ceramics, and the methodology will be explained further in Section 10.4. To avoid complications due to the microstructure, ideally, large-grained, single-phase materials or single crystals should be used to also eliminate any influence of grain size (see [40]).

Figure 10.6. Scanning electron micrograph of a 50 mN indent in ZrB2 showing multiple slip lines in three orientations formed by dislocations surfacing close to the indent.

Before discussing plasticity, the variation of the hardness of UHTCs with temperature will be described. Figure 10.7a–c shows hardness data collected from the literature for borides, carbides, and nitrides as a function of temperature. Many more measurements of room-temperature hardness were reported, but only measurements as a function of temperature have been included here for clarity.

Figure 10.7. Hardness variation with temperature of UHTCs: (a) diborides, (b) carbides, and (c) nitrides. Data from Refs. [37, 41–47].

Near room temperature, the hardness of all UHTCs is quite high (20–35 GPa). As the temperature increases, the decrease in hardness is rapid; by 1000 K, the remaining hardness is of the order of 5 GPa. Data for diborides suggests that the hardness decreases at a reduced rate between 1000 and 1750 K and reduces more rapidly again thereafter. The same trend is not as clear for the carbides. Not enough data for the nitrides is available to come to any conclusion. The initial rapid decay is related to the resistance of the lattice to dislocation motion. Therefore, first, the relation between hardness and yield stress will need to be explored before continuing the discussion in terms of the resistance to dislocation flow.

10.4 Hardness and Yield Strength

Tabor showed using slip line theory that the hardness of metals is approximately three times the yield strength [24]. Since yield strength is a kinetic property of the material that is a function of deformation rate and history, this definition required more care in further work. Tabor and Atkins [48] showed that the amount of strain hardening varies with the geometry of the indenter. For a Vickers or Berkovich indenter, hardness is a measure for the yield strength after 8–10% additional plastic strain. This correlation has later been confirmed by extensive finite element calculations [49].

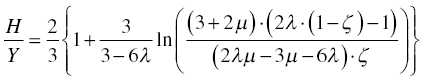

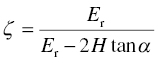

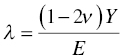

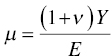

When Marsh [50] tried to apply the same proportionality to the hardness of glass fibers, yield strength was predicted to be below the observed brittle fracture strength, which means that glass should deform rather than fracture. Fortunately, he realized that the theory derived for metals, which have a relatively modest yield strength, Y, compared to their stiffness, E, might not apply to ceramics where the yield strength is a more substantial fraction of the stiffness. As a result in metals, elastic deformation before the onset of plasticity is negligible, and the material displaced by the indenter is forced out of the indented surface forming a pileup of material next to the indentation. When elastic strains preceding plasticity are substantial, the material surrounding the indentation will recede by elastic strain and create space into which deformed material can flow. This led him to propose that indentation in materials where Y/E is high can be thought of as the expansion of a cavity under gas pressure in an infinite body for which Hill had derived a theoretical solution [51]. However, Hill's solution can't be used directly because indentation only produces half a cavity and, therefore, a free surface that can move in the direction of indentation. Johnson [52] was the first to propose a theoretical way to modify the spherical cavity to account for the free surface but overestimated the effect. The treatment by Vandeperre et al. [53] agrees much better with available relationships derived by finite element calculations (Fig. 10.8). Their analytical relationship between hardness and yield strength is

Figure 10.8. Hardness, H, over elastic modulus, E, as a function of the ratio of the yield strength, Y, to the elastic modulus according to the models of Tabor [24], Johnson [52], and Vandeperre, Giuliani, and Clegg [53]. For the latter, the effect of Poisson's ratio is shown with the lower curve for ν = 0 and the upper curve for ν = 0.5. Also shown is the finite element calculation of the relationship taken from Ref. [54–56].

with

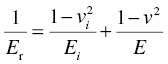

where E is Young's modulus, ν is Poisson's ratio, α is the included equivalent semiangle of the indenter, and Er is the reduced modulus of the contact defined itself as

with Ei and νi as Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio of the indenter.

The key to the success of the latter treatment is that it recognizes that elastic deformation of the surface reduces the amount of material that needs to be displaced by plastic flow for a fixed penetration of the indenter. So, for low Y/E (<0.01), no elastic surface deformation occurs, and the entire penetration of the indenter must be accommodated by plastic flow of material. In contrast, when Y/E becomes high (>0.1), then the entire penetration of the indenter into the material is accommodated by deflection of the surface. The latter is observed in rubbers in which the relation between hardness and yield strength is lost and hardness becomes a measure of E and indenter shape alone. For very low values of Y/E, the expanding cavity-based model predicts that hardness would be more than three times the yield strength, which shows that the hemispherical flow of material would require a higher hardness than the formation of a pileup, thereby explaining the change in flow patterns from hemispherical flow to flow toward the surface when Y/E decreases. Once the change in displaced volume is accounted for, the hardness becomes a smaller multiple of the yield strength for Y/E values typical for ceramics, which explains why glass need not be very hard for its yield strength to be well above its fracture strength.

10.5 Deformation Mechanism Maps

Plastic flow in ceramics, like in any other crystalline material, is normally carried by the movement of dislocations. Although other deformation mechanisms such as twinning [57, 58], phase transformations [59, 60], and densification [61] can play a role, these have not been reported for UHTCs and are therefore not included in this discussion. Deformation mechanisms maps are concise way of representing the dominant deformation mechanisms as a function of temperature, strain rate, and shear stress. These maps, introduced by Ashby and Frost [62], are plots containing lines of constant value of one of the three parameters as a function of the two other parameters. The treatment given here follows mostly the approach of Ashby and Frost, and their book contains much more information. The treatment here differs in that the lattice resistance is described slightly differently and more creep mechanisms are considered. To aid the understanding of the maps, the equations that govern the different mechanisms controlling deformation will be presented and related to hardness data for ZrB2. Following this, maps for ZrB2 and ZrC as assessed in the literature [62, 63] will be compared as examples for the behavior of diborides and carbides. Unfortunately, for nitrides, experimental data are too limited to make a sensible stab at a deformation mechanism map.

10.6 Lattice Resistance to Dislocation Glide

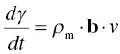

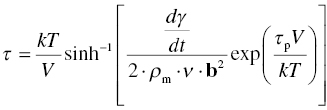

Dislocations can only move if they can at least overcome the resistance of the lattice. The process can be described by considering the rate at which dislocations will be able to flow. A simple theory can therefore be derived starting from Orowan's relation between the velocity of the dislocations, v, and the strain rate, dγ/dt:

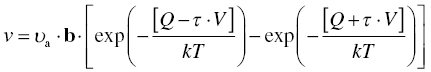

where ρm is the mobile dislocation density and b the Burgers vector. The velocity of the dislocations will be determined by the rate at which they can overcome the rate-determining obstacle. Treating the movement of the dislocation as any other kinetic process involving an activation energy barrier and activation by stress and by counting both the jumps over a distance b in the direction of the applied stress and the jumps over a distance b against the applied stress, the following expression for the velocity is obtained:

where υa is the attempt frequency by which the dislocation tries the move, Q is the activation energy barrier, τ is the applied shear stress, V is the activation volume, k is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature.

The resistance of the lattice, also termed Peierls stress, can be substantial, but the activation energy associated with it, Q, is normally not very high so that thermal energy alone, kT, can have a substantial influence on the stress required to make the dislocations move [62]. Indeed, fcc metals remain ductile even when tested in liquid nitrogen (77 K) because their lattice resistance is limited and reduced to effectively zero very rapidly. In contrast, bcc metals, for which the activation energy of the lattice resistance is in the range 0.5–1.13 eV [62], show a brittle-to-ductile transition temperature (BDTT) caused, in part, by the rapid rise in lattice resistance around the BDTT. Other obstacles to plastic flow such as forest dislocations and second-phase particles tend to have fairly high activation energy barriers (~6 to 40 eV [62]), and their resistance is, therefore, not very temperature dependent [62].

Hence, the high hardness of ceramics near room temperature and the rapid decrease in hardness are entirely consistent with it being controlled by lattice resistance.

Since the lattice resistance or Peierls stress is defined as the stress needed to make the dislocation move at absolute zero, the activation energy barrier can be equated to

Substitution of (Eq. 10.4) into (Eq. 10.3) and (Eq. 10.3) into (Eq. 10.2) and solving for the flow stress yields

This expression can be simplified if it is assumed that the movement of the dislocations against the applied stress is negligible compared to movement along with the stress and that the activation volume can be considered to be independent of temperature. These assumptions lead to the following expression:

which shows that lattice resistance decreases linearly with temperature, in agreement with the steep decrease in hardness. The activation volume can be determined from measurements of the flow stress for different strain rates at fixed temperature and the product ρm ⋅ υa ⋅ b2 from the slope of the decay in flow stress with temperature for a fixed strain rate, and the Peierls stress can be found from the intersection at 0 K from such experiments.

Hence, full characterization of the kinetics of plastic flow controlled by the lattice resistance requires measurements as a function of strain rate. Bhakhri et al. [41] discuss how this is possible using modern indenters, which record load and displacement during an indentation experiment so that the strain rate dependence of hardness can be determined. In deriving the strain rate for ceramic materials, again, the elastic nature of the indentation process needs to be accounted for as only the strain rate due to plastic deformation should be used. Their results for ZrB2 are shown in Figure 10.9 and illustrate that strain rate does influence the hardness at moderate temperatures (<1000 K) as expected for lattice resistance-controlled hardness. They estimate the Peierls stress of ZrB2 as 6.6 ± 0.7 GPa and the activation energy as 1.6 ± 1 eV.

Figure 10.9. Hardness of ZrB2 as a function of plastic strain rate. Data taken from Bhakhri et al. [41].

The hardness data available for UHTCs, in general, does not include information on the strain rate dependence. However, estimates for the Peierls stress and activation energy can still be made by fitting Equation 10.11 to flow stress data derived from the hardness. Since standard hardness measurement procedures tend to use larger loads and short times (10 s), it was assumed in the analysis that the strain rate was fairly high (10−1 s−1), which can affect estimates for the activation energy, but not the Peierls stress. Estimates for the Peierls stress, on the other hand, might have been affected by the presence of rather limited data, so the values given in Table 10.5 are really only estimates.

Table 10.5. Average shear modulus (G), Peierls stress (τp), activation energy (Q), slip planes, and Burgers vector (b) for UHTCs

| Material | G (GPa) | τp (GPa) | Q (eV) | τp/G | Slip plane | Burgers vector (nm) | |||||||

| Carbides | |||||||||||||

| TaC | 195 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 0.021 | {111}, {110} |  |

0.321 | ||||||

| NbC | 167 | 6.3 | 1.5 | 0.037 | {111}, {110} |  |

0.316 | ||||||

| ZrC | 168 | 6.0 | 1.6 | 0.036 | {111}, {110} |  |

0.332 | ||||||

| HfC | 186 | 6.0 | 1.2 | 0.032 | {111}, {110} |  |

0.328 | ||||||

| Nitrides | |||||||||||||

| ZrN | 153 | 8.2 | 1.6 | 0.054 | {110} |  |

0.325 | ||||||

| TaN | 102 | 8.2 | 1.6 | 0.080 | {110} |  |

0.325 | ||||||

| HfN | 153 | 8.5 | 1.6 | 0.056 | {110} |  |

0.320 | ||||||

| Diborides | |||||||||||||

| ZrB2 | 257 | 6.6 | 1.6 | 0.025 | (0001),  |

|

0.317 | ||||||

| TiB2 | 259 | 6.9 | 1.7 | 0.026 | (0001),  |

|

0.303 | ||||||

| HfB2 | 236 | 7.5 | 1.6 | 0.032 | (0001),  |

|

0.314 | ||||||

Main slip system information from Refs. [37, 39, 64–67].

What is clear is that the Peierls stress is of the same order of magnitude for most UHTCs (6–8 GPa). Within one group of materials, this could have been expected. The Peierls model for the lattice resistance predicts that it should only depend on the ratio of the Burgers vector, b, and the slip plane spacing, d, and the shear modulus [68, 69]. Assuming that slip in all the carbides occurs by partial dislocations ½a <1–10> on (111) or (110) planes [2, 62], the ratio b/d will be constant, and hence, the Peierls model predicts that the Peierls stress should only scale with the shear modulus. Since the latter is quite similar for all, similar Peierls stresses are to be expected. The exceptionally low value for the Peierls stress of TaC is probably lower than it should be as a result of very limited hardness data so that the fit is unreliable. Although the nitrides also have rock salt structure and, hence, can be expected to behave like the carbides, their bonding is more ionic, and therefore, slip along {110} planes is favored over slip along {111} planes [70], that is, over planes with large spacing d. This is expected to give a lower Peierls stress, but experimentally, their Peierls stress appears to be a larger fraction of the shear modulus than the carbides. However, some care is needed as all nitride data were obtained from thin films rather than from bulk ceramics and these can be affected by residual stresses.

The crystal structure and slip system of the borides are quite different. The Burgers vector has been identified as  [65], that is, one of the a vectors of the hexagonal unit cell of the crystal, and slip occurs on both the basal plane and the (10-10) prism planes [37, 38, 65]. The fact that the ratio of the Peierls stress to the shear modulus is different for these materials is, therefore, not surprising, and the boride values are reasonably close to each other as are their shear moduli.

[65], that is, one of the a vectors of the hexagonal unit cell of the crystal, and slip occurs on both the basal plane and the (10-10) prism planes [37, 38, 65]. The fact that the ratio of the Peierls stress to the shear modulus is different for these materials is, therefore, not surprising, and the boride values are reasonably close to each other as are their shear moduli.

The activation energies are all around 1.6 eV for the simple reason that, without strain rate information, it is difficult to estimate this parameter more accurately. However, given that the decay in hardness with temperature is similar across all systems, this estimate is certainly of the right order of magnitude.

The high values of the shear stress needed to move dislocations even only one Burgers vector in the crystal explain why at room temperature plasticity is only observed under exceptional circumstances such as during indentation where a compressive stress field for small indents suppresses cracking. This is not without significance as loading by small particles is quite common in wear and the good resistance to dislocation flow can contribute to a high wear resistance [71]. Nevertheless, the stresses needed to grow a crack—maximum fracture strengths are of the order of 1 GPa [72]—are much lower than those needed to make dislocations move, so in many cases, the UHTCs will be brittle at room temperature.

10.7 Dislocation Glide Controlled by Other Obstacles

The dashed lines marked lattice resistance in Figure 10.10 were calculated using (Eq. 10.11) and illustrate that the lattice resistance drops so strongly with temperature that even at fairly low temperatures (0.1–0.3 Tm), it becomes insignificant. It would be tempting to predict that at relatively low temperature, a transition from brittle to ductile should be observed.

Figure 10.10. Deformation mechanism map for ZrB2 recalculated based on the assessment of Wang [63]. Experimental data taken from the following sources: hardness [41, 44, 73, 74] and creep and flow stress measurements [65, 75].

However, the lattice resistance is not the only resistance that dislocations must overcome to move through a material as otherwise fcc metals would always be extremely soft and would not be useful structural materials. Other obstacles to the movement of dislocations include other dislocations forming locks, solute atoms, secondary-phase precipitates, and grain boundaries [76]. Hence, when the lattice resistance decays, the resistance to dislocation motion becomes dominated by the resistance due to these other obstacles. A transition to ductile behavior will, therefore, only be observed if the stresses needed to overcome the latter are lower than the stresses needed to activate crack growth.

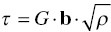

Since dislocation densities underneath indentations tend to be high (see Fig. 10.5), it is reasonable to expect that in hardness tests the main strengthening mechanism would be strain hardening with an associated shear flow stress given by

Given that dislocation densities in heavily deformed material easily reach 1014 m2 [77, 78], τ/G is estimated to be of the order 3 × 10−3, which agrees reasonably with the value for the section where the shear flow stress appears to show limited temperature dependence in Figure 10.10. Since this corresponds to a uniaxial applied stress of 1.54 GPa, which is higher than the highest strengths measured, reaching gross plasticity is still not expected.

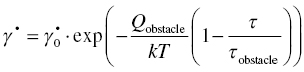

An alternative approach to describing the resistance of other obstacles, taken by Ashby and Frost [62], is to use a single descriptive equation similar in nature to the one derived for glide controlled by the lattice resistance:

where τobstacle as before is the shear stress needed to overcome the obstacle resistance without thermal energy. To account for the more a thermal nature of the resistance by these other obstacles, the value of the activation energy, Qobstacle, is set to a much higher value than that of the lattice resistance. For dislocation-strengthened materials, Ashby and Frost use 0.2–1 × G.b3. The solid lines for the plasticity region in Figure 10.10 were calculated by summing the shear stress needed to overcome the lattice resistance and the shear stress needed to overcome the obstacles as flow is only possible if both resistances are overcome at the same rate.

10.8 Deformation by Creep

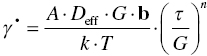

At even higher temperatures, dislocations can escape from obstacles by climb, and, therefore, deformation can occur at lower stresses at a rate normally determined by diffusion of vacancies to aid the climb. This regime, termed power law creep, can be described effectively by

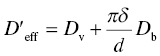

where A is a constant and the effective coefficient of diffusion, Deff, is given by

The latter accounts for both bulk diffusion through the bulk diffusion coefficient Dv and diffusion along the dislocation core through the second term, which takes into account the core area of the dislocation ac and the diffusion coefficient through the core Dc. Hence, at low temperatures, diffusion through the core of the dislocation dominates and the power law has an exponent equal to n + 2, whereas at higher temperatures, bulk diffusion dominates and the exponent is only n. As can be seen in Figure 10.10, the second region where a strong decrease in flow stress occurs in diborides is believed to coincide with the onset of power law creep [63].

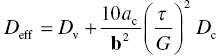

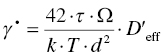

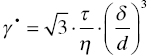

Power law creep is not the only creep mechanism. An obvious alternative to mass transport by dislocations is mass transport by diffusion under influence of a stress, which can be described by [62]

where d is the grain size, Ω is the atomic volume, and the effective diffusion coefficient, D′eff, is given by the weighted average of bulk and grain boundary diffusion:

with δ as the grain boundary thickness. Again, two mechanisms of creep are captured in a single equation: when grain boundary diffusion dominates (Coble creep), the creep rate is inversely proportional to the third power of the grain size, whereas if bulk diffusion dominates (Nabarro–Herring creep), the creep rate is only inversely proportional to the second power of the grain size. In both cases, the creep rate is directly proportional to the stress, that is, the stress exponent can be said to be equal to 1.

Another creep mechanism that is very common in ceramic materials is creep due to the presence of viscous material on the grain boundaries [79, 80]. In such instances, creep can be caused by dissolution in a region of compressive stress, transport of the material through the viscous grain boundary, and precipitation in the tensile regions or by viscous flow of the grain boundary glass [81]. Indeed, a stress exponent of 1 is also consistent with creep accommodated entirely by viscous flow of the glassy material from the compressive to the tensile surfaces of the grains with creep rates given by [80–83].

where τ is the applied shear stress, τ is the viscosity, δ is the thickness of the grain boundary film, and d is the grain size. Note that in terms of stress and grain size dependence, the behavior is similar to what is observed for Coble creep. This mechanism is not recognized as a true deformation mechanism by all because it is not self-sustaining: once all viscous liquid has been squeezed out of the compressive regions, deformation by this mechanism comes to a halt. However, strains in excess of the typical failure strains can be accumulated for quite normal contents of viscous material [81]. These viscous mechanisms have not been added to the maps since TEM evidence suggests that such viscous phases are limited in pure UHTCs, provided surface oxides are removed during processing [63].

Since each of these creep rates occurs independently, the creep rates from all mechanisms should in principle be added, but in the maps shown in this chapter, only the dominant mechanism is shown. This only causes small differences to the map as the contributions of minor mechanism are only important in the transition regions.

10.9 Deformation of Carbides versus Borides

The deformation mechanism map for ZrB2 shown in Figure 10.10 should be contrasted with the deformation mechanism map for ZrC as assessed by Ashby and Frost [62] in Figure 10.11. The parameters used for constructing both maps are summarized in Table 10.6.

Figure 10.11. Deformation mechanism map for ZrC recalculated using the assessment of Ashby and Frost [62]. Experimental data taken from the following sources: hardness [45] and creep and flow stress measurements [66, 84, 85].

Table 10.6. Parameters used to construct the deformation mechanism maps. Parameters for ZrB2 from Ref. [63] and for ZrC from Ref. [62]. Where the treatment deviates from Ashby and Frost, parameters were adapted to get coincidence of the maps.

| Parameter | ZrB2 | ZrC |

| General information | ||

| Melting point, Tm | 3505 K | 3530 K |

| Lattice parameters | ||

| a | 0.317 nm | 0.4698 nm |

| c | 0.353 nm | (n/a) |

| Burgers vector, b | 0.317 nm | 0.334 nm |

| Atomic volume, Ω | 0.0154 nm | 0.0264 nm3 |

| Shear modulus at RT, G | 257 GPa | 173 GPa |

| dG/dT | −0.025 GPa K−1 | −0.0139 GPa K−1 |

| Grain size | 20 µm | 10 µm |

| Bulk diffusion | ||

| Pre-exponential factor Dv,0 | 5 m2 s−1 | 1.03 × 10−1 m2 s−1 |

| Activation energy, Qv | 678 kJ mol−1 | 720 kJ mol−1 |

| Grain boundary diffusion | ||

| Pre-exponential factor δ × Dgb,0 | a | 5.0 × 10−12 m3s−1 |

| Activation energy, Qgb | 468 kJ mol−1 | |

| Dislocation core diffusion | ||

| Pre-exponential factor ac × Dc,0 | a | 1.0 × 10−21 m4s−1 |

| Activation energy, Qc | 468 kJ mol−1 | |

| Power law creep | ||

| Dorn constant | 1013 | 1012 |

| Exponent | 7.38 | 5 |

| Lattice resistance-controlled glide | ||

| Peierls stress, τp | 6.6 GPa | 6.92 GPa |

| Activation energy, Q | 1.61 eV | 1.40 eV |

| Attempt frequency, νa | 1011 s−1 | 1011 s−1 |

| Mobile dislocation density, ρm | 1014 m−2 | 1014 m−2 |

| Obstacle-controlled glide | ||

| Critical shear stress at 0 K, τ^ | 1 GPa | 578 MPa |

| Pre-exponential γ0 | 108 s−1 | 108 s−1 |

| Activation energy | 51 eV | 40 eV |

a Not included in assessment.

Two major differences exist. The first is that in the map for ZrB2, deformation by diffusion is estimated to dominate for much higher stresses than for ZrC. The second is that ZrC shows creep deformation at a much reduced temperature with two very distinct regions of low- and high-temperature creep. For ZrB2, power law creep requires higher temperatures, and it is not clear whether much distinction must be made between high- and low-temperature creep—in the assessment, only high-temperature creep was considered.

The fact that the transition metal carbides have a poor creep resistance is well established [62]. The map for ZrB2 does not include creep at low temperature because the hardness variation with temperature is so different as commented on before: for all of the diborides, the hardness is found to almost not decrease between 500 and 1750 K. The fact that several authors observed this plateau-like region suggests strongly that the creep resistance of the diborides is indeed much better than that of the carbides, whose hardness drops almost at a fixed rate until below 1 GPa.

The reasons given for the extended role for diffusion in the ZrB2 assessment were [63] (i) the fact that ZrB2 sinters at 2273 K is evidence that flow by diffusion is possible in that region; (ii) that TEM observation of samples from hardness measurements showed limited dislocations when deformed at 2273 K, whereas dislocations were seen at lower temperatures; and (iii) the fact that the stress exponent in creep measurements by Rhodes et al. [17] (~2) was consistent with diffusion creep transiting into power law creep and, hence, a transition into diffusional creep at relatively high stress. Of these, the latter was the more important as it strongly confirms that diffusion does play a role to much higher stresses. The stress exponent of the creep data from Talmy [75] shown in Figure 10.10 was again indicative of creep controlled by diffusion, and therefore, this additional data point largely confirms the position of the creep controlled by diffusion in the map.

It is worth pointing out that α-Al2O3 is a trigonal crystal (space group  ) and, therefore, has a certain level of structural similarity to the hexagonal diborides. This compound shows deformation on similar slip systems to the transition metal diborides (on the basal and prism planes) [86]. It also shows a much larger region in which diffusion controls the deformation in the map by Ashby and Frost [62], indicating that diffusion does play a role to much higher stresses in similar materials too.

) and, therefore, has a certain level of structural similarity to the hexagonal diborides. This compound shows deformation on similar slip systems to the transition metal diborides (on the basal and prism planes) [86]. It also shows a much larger region in which diffusion controls the deformation in the map by Ashby and Frost [62], indicating that diffusion does play a role to much higher stresses in similar materials too.

Finally, Miloserdin et al. [84] claimed diffusional creep as the mechanism for their results, while on the ZrC map, their data is lodged firmly in the power law creep region. Ashby and Frost did not include this data in their assessment, and hence, perhaps the diffusional region of carbides should extend to higher stresses, which would reduce the difference somewhat.

10.10 Conclusions

The carbides, diborides, and nitrides of the transition metals are all reasonably isotropic in their response to elastic loading and quite stiff and show only a limited reduction of about 1% per 100 K in elastic properties.

Small-scale measurements of hardness (100–200 mN) give a good indication of the deformation behavior at moderately elevated temperatures (~600 K) and in combination with strain rate-dependent measurements can give good estimates for the lattice resistance to dislocation motion. Measurements of the hardness at higher temperatures can also aid in the identification of transitions toward other deformation mechanisms such as power law creep and creep by diffusion and therefore are a powerful tool for determination of deformation mechanism maps. A comparison of maps for carbides and for diborides revealed that the latter are much more creep resistant and that diffusion appears to play a more important role in their deformation behavior.

References

- 1. Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Talmy IG, Zaykoski JA. Refractory diborides of zirconium and hafnium. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (5):1347–1364.

- 2. Kelly A, Groves GW, Kidd P. Crystallography and Crystal Defects. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2000. p 470.

- 3. Hearmon RFS. Equations for transforming elastic and piezoelectric constants of crystals. Acta Cryst 1957;10 (2):121–125.

- 4. Bhardwaj P, Singh S. Structural phase stability and elastic properties of refractory carbides. Int J Refract Metals Hard Mater 2012;35:115–121.

- 5. Srivastava A, Diwan BD. Elastic and thermodynamic properties of divalent transition metal carbides MC (M = Ti, Zr, Hf, V, Nb, Ta). Can J Phys 2012;90:331–338.

- 6. Landolt H, Elektrische B. Piezoelektrische, pyroelektrische, piezooptische, elektrooptische konstanten und nichtlineare dielektrische suszeptibilitaten. Zahlenwerte Funktionen Naturwissenschaft Technik 1979;Gruppe(III):11.

- 7. Weber W. Lattice dynamics of transition metal carbides. Phys Rev B 1973;8 (11):5082–5092.

- 8. Lopez-de-la-Torre L, Winkler B, Schreuer J, Knorr K, Avalos-Borja M. Elastic properties of tantalum carbide (TaC). Solid State Commun 2005;134:245–250.

- 9. Holec D, Friak M, Neugebauer J, Mayrhofer PH. Trends in the elastic response of binary early transition metal nitrides. Phys Rev B 2012;85:064101.

- 10. Chen W, Jiang JZ. Elastic properties and electronic structures of 4d- and 5d-transition metal mononitrides. J Alloys Compd 2010;499:243–254.

- 11. Chang J, Zhao G-P, Zhou X-L, Ke L, Lu L-Y. Structure and mechanical properties of tantalum mononitride under high pressure: a first principles study. J Appl Phys 2012;112:083519.

- 12. Okamoto NL, Kusakari M, Tanaka K, Inui H, Yamaguchi M. Temperature dependence of thermal expansion and elastic constants of single crystals of ZrB2 and the suitability of ZrB2 as a substrate for GaN films. J Appl Phys 2003;93 (1):88–93.

- 13. Lawson JW, Bauschlicher CH Jr, Daw MS. Ab initio computations of electronic, mechanical and thermal properties of ZrB2 and HfB2. J Am Ceram Soc 2011;94 (10):3494–3499.

- 14. Zhang J-D, Cheng X-L, Li D-H. First-principles study of the elastic and thermodynamic properties of HfB2 with AlB2 structure under high pressure. J Alloys Compd 2011;509:9577–9582.

- 15. Waskowska A, Gerward L, Olsen JS, Babu KR, Vaitheeswaran G, Kanchana V, Svane A, Filipov VB, Levchenko G, Lyaschenko A. Thermoelastic properties of ScB2, TiB2, YB4 and HoB4: experimental and theoretical studies. Acta Mater 2011;59:4886–4894.

- 16. Neuman EW, Hilmas GE, Fahrenholtz WG. Strength of zirconium diboride to 2300°C. J Am Ceram Soc 2013;96 (1):47–50.

- 17. Rhodes WH, Clougherty EV, Kalish D. Research and development of refractory oxidation-resistant diborides. Part II. Volume IV. Mechanical properties. Technical Report. September 15, 1967–May 15, 1969. Other Information: UNCL. Original Receipt Date: June 30, 1973. 1970. Medium: X; Size: p. 153.

- 18. Wiley DE, Manning WR, Hunter O. Elastic properties of polycrystalline TiB2, ZrB2 and HfB2 from room temperature to 1300 K. J Less Common Metals 1969;18:149–157.

- 19. Roebben G, Bollen B, Brebels A, Van Humbeeck J, Van der Biest O. Impulse Excitation apparatus to measure resonant frequencies, elastic moduli, and internal friction. Rev Sci Instrum 1997;68 (12):4511–4515.

- 20. Wuchina E, Opeka M, Causey S, Buesking K, Spain J, Cull A, Routbort J. Guitierrez-m-Morea. Designing for ultrahigh-temperature applications: the mechanical and thermal properties of HfB2, HfNx. J Mater Sci 2004;39:5939–5949.

- 21. Dodd SP, Cankurtaran M. Ultrasonic determination of the elastic and nonlinear acoustic properties of transition-metal carbide ceramics: TiC and TaC. J Mater Sci 2003;8:1007–1115.

- 22. Jun CK, Shafffer PTB. Elastic moduli of niobium carbide and tantalum carbide. J Less Common Metals 1971;23:367–373.

- 23. Baranov VM, Knyazev VI. The temperature dependence of the elastic constants of nonstoichiometric zirconium carbides. Probl Prochn 1973;9:45–47.

- 24. Tabor D. The physical meaning of indentation and scratch tests. Br J Appl Phys 1956;7:159–166.

- 25. Sangwal K. Review: indentation size effect, indentation cracks and microhardness measurement of brittle crystalline solids—some basic concepts and trends. Cryst Res Technol 2009;44 (10):1019–1037.

- 26. Krell A. A new look at grain size and load effects in the hardness of ceramics. Mater Sci Eng 1998;A245 (2):277–284.

- 27. Krell A. A new look at the influences of load, grain size, and grain boundaries on the room temperature hardness of ceramics. Int J Refract Metals Hard Mater 1998;16 (4–6):331–336.

- 28. Li H, Bradt RC. The microhardness indentation load/size effect in rutile and cassiterite single crystals. J Mater Sci 1993;28:917–926.

- 29. Sangwal K. On the reverse indentation size effect and microhardness measurement of solids. Mater Chem Phys 2000;63:145–152.

- 30. Chen J, Bull SJ. A critical examination of the relationship between plastic deformation zone size and Young's modulus to hardness ratio in indentation testing. J Mater Res 2006;21 (10):2617–2627.

- 31. Quinn GD, Green P, Xu K. Cracking and the indentation size effect for knoop hardness of glasses. J Am Ceram Soc 2003;86 (3):441–448.

- 32. Wang J, Giuliani F, Vandeperre LJ. The effect of load and temperature on hardness of ZrB2 composites. Ceram Eng Sci Proc 2010;31 (2):59–68.

- 33. Anstis GR, Chantikul P, Lawn B, Marshall DB. A critical evaluation of indentation techniques for measuring fracture toughness: I. Direct crack measurements. J Am Ceram Soc 1981;64 (9):533–538.

- 34. Niihara K, Morena R, Hasselman DPH. Evaluation of KIC of brittle solids by the indentation method with low crack-to-indent ratios. J Mater Sci Lett 1982;1:13–16.

- 35. Morris DJ, Myers SB, Cook RF. Sharp probes of varying acuity: instrumented indentation and fracture behavior. J Mater Res 2004;19 (1):165–175.

- 36. Rice RW. Porosity of ceramics. Materials Engineering. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1998. p 539.

- 37. Wang J, Giuliani F, Vandeperre L. Temperature and strain-rate dependent plasticity of ZrB2 composites from hardness measurements. Ceram Eng Sci Proc 2011;32:137–149.

- 38. Ghosh D, Subhash G, Orlovskaya N. Slip-line spacing in ZrB2-based ultrahigh-temperature ceramics. Scr Mater 2010;62:839–842.

- 39. Ghosh D, Ghatu S, Bourne GR. Room-temperature dislocation activity during mechanical deformation of polycrystalline ultra-high-temperature ceramics. Scr Mater 2009;61:1075–1078.

- 40. Rice RW, Wu C, Borchelt F. Hardness—grain size relations in ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 1994;77 (10):2539–2553.

- 41. Bhakhri V, Wang J, Ur-rehman N, Ciurea C, Giuliani F, Vandeperre L. Instrumented nanoindentation investigation into the mechanical behaviour of ceramics at moderately elevated temperatures. J Mater Res 2012;27 (1):65–75.

- 42. Bsenko L, Lundström T. The high-temperature hardness of ZrB2 and HfB2. J Less Common Metals 1974;34 (2):273–278.

- 43. Chen CH, Xuan Y, Otani S. Temperature and loading time dependence of hardness of LaB6, YB6 and TiC single crystals. J Alloys Compd 2003;350 (1–2):L4–L6.

- 44. Koester RD, Moak DP. Hot hardness of selected borides, oxides, and carbides to 1900°C. J Am Ceram Soc 1967;50 (6):290–296.

- 45. Kumashiro Y, Nagai Y, Kato H. The Vickers micro-hardness of NbC, ZrC and TaC single crystals up to 1500°C. J Mater Sci 1982;1:49–52.

- 46. Koval'chenko MS, Daemelinski VV, Borisenko V. Temperature dependence of the hardness of Titanium, Zirconium, and Hafnium carbides. Probl Prochnosti 1969;5:63–66.

- 47. Quinto DT, Wolfe GJ, Jindal PC. High temperature microhardness of hard coatings produced by physical and chemical vapor deposition. Thin Solid Films 1987;153:19–36.

- 48. Atkins AG, Tabor D. Plastic indentation in metals with cones. J Mech Phys Solids 1965;13:49–164.

- 49. Cheng YT, Cheng CM. Scaling approach to conical indentation in elastic-plastic solids with work hardening. J Appl Phys 1998;84 (3):1284–1291.

- 50. Marsh DM. Plastic flow in glass. Proc R Soc A 1963;279:420–435.

- 51. Hill R. The Mathematical Theory of Plasticity. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1950.

- 52. Johnson KL. The correlation of indentation experiments. J Mech Phys Solids 1970;18:115–126.

- 53. Vandeperre LJ, Giuliani F, Clegg WJ. Effect of elastic surface deformation on the relation between hardness and yield strength. J Mater Res 2004;19 (12):3704–3714.

- 54. Cheng YT, Cheng CM. What is indentation hardness? Surf Coat Technol 2000;133–134:417–424.

- 55. Dao M, Chollacoop N, Vliet KJV, Venkatesh TA, Suresh S. Computational modeling of the forward and reverse problems in instrumented sharp indentation. Acta Mater 2001;49:3899–3918.

- 56. Mata M, Anglada M, Alcala J. A hardness equation for sharp indentation of elastic-power law strain-hardening materials. Philos Magaz 2002;A82 (10):1831–1839.

- 57. Giuliani F, Lloyd SJ, Vandeperre LJ, Clegg WJ. Deformation of GaAs under nanoindentation. In: McVitie S, McComb D, editors. Electron Microscopy and Analysis. Oxford: Institute of Physics; 2003. p 123–126.

- 58. Lloyd SJ, Castellero A, Giuliani F, Long Y, McLaughlin KK, Milina-Aldareguia JM, Stelmashenko NA, Vandeperre LJ, Clegg WJ. Observations of nanoindents via cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy: a survey of deformation mechanisms. Proc R Soc Lond A 2005;61 (2060):2521–2543.

- 59. Lloyd SJ, Molina-Aldareguia JM, Clegg WJ. Under nanoindents in Si, Ge, and GaAs examined through transmission electron microscopy. J Mater Res 2001;16 (12):3347–3350.

- 60. Vandeperre LJ, Giuliani F, Lloyd SJ, Clegg WJ. The hardness of silicon and germanium. Acta Mater 2007;55 (18):6307–6315.

- 61. Suzuki K, Benino Y, Fujiwara T, Komatsu T. Densification energy during nanoindentation of silica glass. J Am Ceram Soc 2002;85 (12):3102–3104.

- 62. Frost HJ, Ashby MF. Deformation Mechanism Maps: The plasticity and Creep of Metals and Ceramics. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1982.

- 63. Wang J. Processing and deformation of ZrB2. London: Department of Materials, Imperial College London; 2012. p 129.

- 64. Vahldiek FW, Mersol SA. Slip and microhardness of IVa to VIa refractory materials. J Less Common Metals 1977;55 (2):265–278.

- 65. Haggerty JS, Lee DW. Plastic deformation of ZrB2 single crystals. J Am Ceram Soc 1971;54 (11):572–576.

- 66. Lee DW, Haggerty JS. Plasticity and creep in single crystals of zirconium carbide. J Am Ceram Soc 1969;52 (12):641–647.

- 67. Molina-Aldareguia JM, Lloyd SJ, Barber ZH, Clegg WJ. Lack of hardening effects in TiN/NbN multilayers. Materials Research Society Fall Meeting November 27-December 1; Boston, MA; Materials Research Society; 2001.

- 68. Cottrell AH. Plastic flow in crystals. In: Fowler RH et al., editors. International Monographs on Physics. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1961. p 223.

- 69. Peierls P. The size of a dislocation. Proc Phys Soc 1940;52:34–37.

- 70. Oden M, Ljungcrantz H, Hultman L. Characterisation of the induced plastic zone in a single crystal TiN(001) film by nanoindentation and transmission electron microscopy. J Mater Res 1997;12 (8):2134–2142.

- 71. Hutchings IM. Tribology: Friction and Wear of Engineering Materials. London: Edward Arnorld; 1992.

- 72. Chamberlain AL, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE. High-strength zirconium diboride-based ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 2004;87 (6):1170–1172.

- 73. Xuan Y, Chen C-H, Otani S. High temperature microhardness of ZrB2 single crystals. J Phys D Appl Phys 2002;35:L98–L100.

- 74. Wang J, Feilden-Irving E, Giuliani F, Vandeperre LJ. The Hardness of zirconium diboride between 1323 K and 2273 K. Ceram Eng Sci Proc 2013;33 (3):187–196.

- 75. Talmy IG, Zaykoski JA, Martin CA. Flexural creep deformation of ZrB2/SiC ceramics in oxidizing atmosphere. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (5):1441–1447.

- 76. Dieter GE. Mechanical Metallurgy. London: McGraw-Hill; 1998. SI Metric edition; p 751.

- 77. Barabash OM, Santella M, Barabash RI, Ice GE, Tischler J. Measuring depth-dependent dislocation densities and elastic strains in an indented Ni-based superalloy. J Miner Metals Mater Soc 2010;62 (12):29–34.

- 78. Dragomir-Cernatescu I, Gheorghe M, Thadhani N, Snyder RL. Dislocation densities and character evolution in copper deformed by rolling under liquid nitrogen from x-ray peak profile analysis. J Int Centre Diffract Data 2005;48:67–72.

- 79. Biswas K, Rixecker G, Aldinger F. Creep and visco-elastic behaviour of LPS-SiC sintered with Lu2O3-AlN additive. Mater Chem Phys 2007;104 (1):10–17.

- 80. de Arellano-Lopez AR, Melendez-Martinez JJ, Cruse TA, Koritala RE, Routbort JL, Goretta KC. Compressive creep of mullite containing Y2O3. Acta Mater 2002;50:4325–4338.

- 81. Dryden JR, Kucerovsky D, Wilkinson DS, Watt DF. Creep deformation due to a viscous grain boundary phase. Acta Metall 1989;7 (7):2007–2015.

- 82. Lofaj F, Wiederhorn SM, Dorcakova F, Hoffmann KJ. The effect of glass composition on creep damage development in silicon nitride ceramics. 11th International Conference on Fracture; Turin; 2005.

- 83. Yoon KJ, Wiederhorn SM, Luecke WE. Comparison of tensile and compressive creep behavior in silicon nitride. J Am Ceram Soc 2000;83 (8):2017–2022.

- 84. Miloserdin YV, Naboichenko KV, Laveikin LI, Bortsov AG. The high-temperature creep of zirconium carbide. Probl Prochn 1972;3:50–53.

- 85. Leipold MH, Nielsen TH. Mechanical properties of hot-pressed zirconium carbide tested to 2600°C. J Am Ceram Soc 1964;47 (9):419–424.

- 86. Lagerlöf KPD, Heuer AH, Castaing J, Rivière JR, Mitchell TE. Slip and twinning in sapphire (α-alumina). J Am Ceram Soc 1994;77 (2):385–397.