While developing his idealistic agenda for re-forming the world around him, the handsome twenty-seven-year-old had moved from the solitary pleasures of horsemanship and gambling in his hussar’s uniform to doing more than simply observe women. On June 4, 1910, at a sanatorium in the Tyrol, he encountered Alma Mahler for the first time. This fetching woman with a pouf of jet-black hair had a way of looking at him that was charged with electricity; Gropius had never before experienced anything like it.

The architect was at the sanatorium because, overworked, he was suffering from a cold that refused to abate. But ill health did not prevent the young man from falling instantly head over heels for Alma. Her husband, the renowned composer and conductor Gustav Mahler, was fifty-one years old to her thirty-one, and she was restless. Her young daughter’s presence did not impede her availability.

Alma Schindler Mahler was a force to reckon with. Her appearance was more fascinating than classical; she had fiery eyes and a vibrant presence that many men found irresistible. Because of her partial deafness, she stood especially close to anyone speaking to her and carefully read the person’s lips, a posture that many men regarded as a sexual invitation. Alma’s early romantic liaisons had included theater director Max Burckhard and composer Alexander von Zemlinsky. She had married Gustav Mahler in 1902, when he was director of the Vienna Court Opera.

For Alma, an essential ingredient of male greatness was artistic creativity. As a child she deified her father, Emil Jakob Schindler, a landscape painter who did well enough with his art to bring up his family stylishly in a castle on the outskirts of Vienna, where he devoted almost as much energy to throwing lavish parties as to painting. Alma never recovered from the jolt of his sudden death when she was thirteen.

She had far less regard for her mother, Anna. When her younger sister Grete was put into an asylum following two suicide attempts, her mother said the reason for Grete’s illness was that her father (who was not Schindler) had syphilis. Alma held Anna in contempt, and resented her all the more for marrying yet another former lover, the painter Carl Moll, soon after Schindler’s death. Moll had been a student of Schindler’s when he and Alma’s mother first had an affair.

At least Moll, who was a major figure in the contemporary art scene in Vienna, attracted interesting people to the house. Young Alma gave her first kiss to the painter Gustav Klimt, whom she met when she was seventeen. Klimt had recently become president of the Secession, an artistic movement he had conceived with Moll and a third artist, Josef Engelhardt. Its goal was to break away from the traditional academic style that dominated the artistic establishment in Vienna. Alma was by nature attracted to rebellious groundbreakers who were in positions of power (Gropius would be a prime exemplar), and it’s no surprise that the painter fell for her in return. Klimt deliberately confronted societal norms—he sported a fringe beard and wore voluminous monk’s robes—and considered his colleague’s teenage stepdaughter a perfect quarry. The slightly oversize features that made her face so riveting, her unabashed mischief, and her skill at singing Wagner with her mezzo-soprano voice enchanted him to the point of obsession.

When Alma’s mother and Moll heard about her kissing the painter, who was more than twice her age, they tried to put an end to the relationship, to which Klimt responded with a letter saying that Alma was “everything a man can wish for in a woman, and in abundant measure.”8 Alexander von Zemlinsky, who was Alma’s music teacher, was also obsessed with her. Although Alma considered him “a hideous gnome,”9 a private rendition he gave her of Tristan led to passionate embraces.

Alma remained a virgin, but it was a struggle. Even at an early age, the future first lady of the Bauhaus confessed her sexual longings in her diary. While she would not allow Zemlinsky full intercourse, she wrote, “I madly desire his embraces, I shall never forget the feel of his hand deep in my innermost self like a torrent of flames! … Perfect bliss does exist! …I would like to kneel down before him and press my lips to his naked body, kiss everything, everything! Amen!” Although she would have been “in the seventh heaven” if she had allowed him to bring her to orgasm, she would not give him “the hour of happiness” he craved.10 The reason was that she had met Gustav Mahler.

In February 1901, Alma, age twenty, saw the forty-one-year-old tyrant with famously unruly hair and unkempt clothing conduct the Vienna Philharmonic in The Magic Flute. While most young women were repulsed by Mahler, Alma, noting his “Lucifer face” and “glowing eyes,” was completely thrilled.11 Without knowing that his agonized expression was caused by his deep hemorrhoids and the onset of a rectal hemorrhage, she realized that he was someone of unequaled intensity and made it her mission to rescue him.

Later that year, a friend of Alma’s, the journalist Berta Zuckerkandl, organized a meeting between Mahler and Alma. The two began a tempestuous courtship. At the start, Zemlinsky was still very much a player; as Walter Gropius would discover, initially to his advantage, Alma required the simultaneous presence of at least two ardent pursuers.

ALMA SCHINDLER AND GUSTAV MAHLER were married in March 1902. It was a small private ceremony, designed to keep the press at bay, for Mahler was already a Viennese celebrity. Alma agreed to give up her own wish to compose in order to support her husband’s work, and while Mahler composed and conducted and toured, she practiced diplomacy on his behalf. When Mahler sulked silently at public dinners or stormed out in the middle of them, Alma smoothed the waters. Her striking looks helped distract people from Mahler’s unpleasantness on his New York tour; the pianist Samuel Chotzinoff called her “the most beautiful woman I have ever seen”—a complete contrast to the husband who was enthralling in “the force of his genius,” but, besides being awkward and homely, was given to fits of rage.12

The Mahlers soon had two daughters, and for a while all went well. Then, in 1907, the older girl died of diphtheria. Alma began to suffer from deep depressions. Her spirits further declined when, in a splendid concert hall in Paris, during the middle of the second movement of Mahler’s Second Symphony, Claude Debussy—who had been Alma’s dinner partner the night before—walked out conspicuously, as did the two other French composers, Paul Dukas and Gabriel Pierné, who were with him. They subsequently explained that the music was “too ‘Schubertian,’ … too Viennese, too Slavonic.” Mahler was devastated. Alma had to pamper him to such an extent that she ended up exhausted. “I was really sick,” she later explained, “utterly worn out by the perpetual motion necessitated by a giant engine such as Mahler’s mind. I simply could not go on.”13 In the spring of 1910, the doctors recommended that she treat her severe melancholy by going to the resort spa of Tobelbad for a rest cure. This was where, in early June, she met Walter Gropius, in an encounter that revived her more effectively than anything the doctors had in mind.

ALMA HAD BEEN COMPLETELY dispirited when she and her little daughter, Anna, known as Gucki, arrived at the spa, in the duchy of Styria in the southern reaches of what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire and is today Slovenia. Despite the beautiful location—a fir forest that blanketed a valley surrounded by mountain peaks—initially Alma showed no signs of rebounding. Neither the diet of lettuce and buttermilk, nor the walks in rain and wind that were supposed to bring her back to health, had any effect, and the baths in hot springs made her faint. Finally, the German doctor in charge of her care resorted to persuading her to dance and meet young men. “One was an extraordinarily handsome German who would have been well cast as Walther von Stolzing in Die Meistersinger,” Alma later recalled.14 Gropius had what it took to bring her back to life.

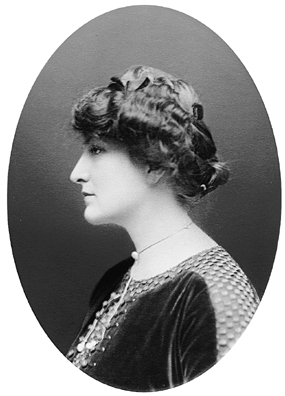

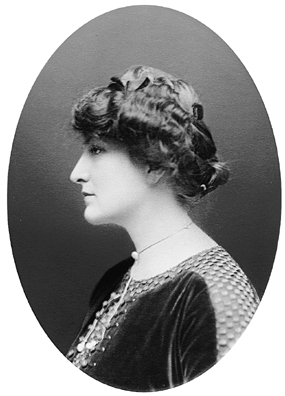

Alma Mahler at the time of her marriage to Gropius. Her profile could have been on a Greek vase, but there was nothing classical about her personality

In Gropius’s arms on the dance floor, the forlorn patient felt her humor change completely. The dashing young man, “handsome, fair-haired, clear-eyed …the son of an eminently respectable Prussian bourgeois family,” was her husband’s opposite.15 As they slowly glided around to the music of the small orchestra, Alma learned that he had studied architecture with a friend of her beloved father’s; she considered it a magical connection.

Then Mrs. Mahler and Walter Gropius went for a walk in the moonlight. They talked until dawn. The young architect’s “aristocratic bearing, unwavering gaze, and restrained demeanor” had their effect on the tormented young mother.16 In return, Alma’s intensity and arresting looks took Gropius by storm.

Gropius stretched his stay at Tobelbad to mid-July. Alma was convinced that no man had ever made her as happy. Her mother, who had arrived at the spa, sanctioned the affair and took care of Gucki so that the lovers could spend entire nights together. When Mahler, who wrote regularly, became anxious over the dearth of mail from the woman he addressed as his “child-wife,”17 his mother-in-law sent a letter reassuring him that all was well but that Alma was too fatigued to be in touch.

Mahler was then composing his Tenth Symphony in Toblach, a village in the Tyrol where he and Alma had a country house. Once Alma returned to him, she and Gropius began sending daily letters back and forth. The longer they were apart, the more fervently they expressed their love.

Alma relished having a lover and a husband at the same time. Mahler had become “more amorous than ever” since her return;18 she attributed his increased ardor to the new allure she had acquired in Gropius’s arms. The combination of the confident young lover and the tormented yet brilliant older husband was ideal.

THEN CAME ONE of the great slip-ups of all time. Walter Gropius put a love letter to Alma Mahler in an envelope that he addressed to “Herr Direktor Mahler.”

When Gustav Mahler returned home from the concert hall one evening, the envelope was on the piano. As soon as he read the incriminating document, he handed it to his wife. He told her he was convinced the so-called mistake was deliberate on the part of the young architect. Mahler believed this was Gropius’s way of asking him to release her, a ploy that enraged him almost as much as the affair itself. Alma was less certain; she didn’t know “whether the youth had gone mad or had subconsciously wanted this letter opened by Mahler himself.”19

Gropius’s letter was full of explicit references to what was going on between him and Alma, and posed the question, “Did your husband not notice anything?”20 Alma answered by writing Gropius that while Mahler had not previously detected the affair, everything had changed because of the misaddressed letter. She demanded that he write her an explanation for the catastrophe, letting her know whether it was a faux pas or by plan, and send it to her private post office box.

IN THE INCIDENT of the letter sent to Gustav Mahler may lie a clue to the real nature of the man who launched the great art school. Alma’s biographer Frangoise Giroud—who maintains, “One thing is certain; it was no accident”—asks, “Was it Mahler he was in love with, through Alma?”21 Gropius’s taste for women married to fascinating husbands would be borne out again at the Bauhaus.

Gropius himself never made any effort to explain what had happened. Meanwhile, in response to the crisis, the Mahlers grew closer. They took long walks on which they both wept, Alma telling all, Gustav blaming himself for having made Alma forsake her own work. Alma let her husband know she now realized she could never leave him; ecstatic, the composer clung to her “every second of the day and night.” Mahler took to writing her love letters; in one he described standing by her bedroom door “with longing” while he kissed her “little slippers a thousand times.”22 He also insisted on keeping the door between their adjoining rooms open at night just so that he could hear her breathe.

During the days, when Alma went to the forest hut where Mahler worked so that she could summon him for meals, she often found him lying on the floor, weeping in fear that he might lose her. But all signs pointed to the marriage lasting, especially when Alma’s mother appeared on the scene to offer them both her support—even if she had abetted the secret liaison with Gropius.

Alma instructed Gropius that under no circumstances was he to come to Toblach. He was not, however, someone who followed instructions. With the resolve and determination that would mark his tenure at the Bauhaus, he showed up anyway. After wandering around town, he went to the Mahlers’ house, where a guard dog chased him away. Alma inadvertently spotted him concealing himself under a bridge. She immediately told Mahler, who ferreted Gropius out of his hiding place and invited him to the house. The swashbuckling former hussar walked up the dark country lane with the bedraggled musical genius who was old enough to be his father. They said nothing to each other. Mahler then left Gropius and Alma alone in the parlor to work out things by themselves.

The lovers spoke only briefly before Gropius left the room and found Mahler, whom he asked to divorce his wife so that she would be free to marry him. When Mahler calmly asked Alma if this was what she wanted, she replied that her lover’s proposal was out of the question and that she would stay with her husband. Mahler led Gropius down the lane up which he had guided him only an hour earlier, the darkness requiring him to carry a lantern. Again the two men walked in complete silence.

The next day, Alma went into Toblach to bid Gropius farewell at his small hotel and accompany him to the train. There is no way of knowing the precise conversation on the platform, but every time the train stopped on the way back to Berlin, Gropius dashed out to wire another telegram to Alma, begging her to reconsider.

THEN THE LYING BEGAN AGAIN. After assuring Mahler that she had renounced her lover completely, Alma continued to write to Gropius. When she and Mahler returned to Vienna, she sent the architect a letter explaining her predicament: “My remaining with him—in spite of all that has happened—means life to him—and my leaving—will be death to him. …Gustav is like a sick, magnificent child. … Oh—when I think about it, my Walter, that I should be without your love for my whole life. Help me—I don’t know what to do—what I have the right to.”23

Alma’s mother, Anna Moll, again became the lovers’ accomplice, so that Gropius, rather than risk having another letter fall into the wrong hands, could now write via this indulgent lady. The pace of their correspondence picked up, and Alma invited Gropius to Vienna. They fell into each other’s arms. The first meeting was followed by another, and another, always in secret. Alma studied her husband’s schedule in order to organize trysts when he was in rehearsal or performing out of town, and she and Gropius invented brilliant pseudonyms to use when registering for their hotel rooms. Physically, Gropius was everything Mahler was not: trim, well toned, impeccably dressed without being a dandy. He was terrifically handsome; even if he considered his nose too large, his well-proportioned features were those of a classical marble sculpture. His sallow complexion and thick, dark, straight hair were striking, and he had made a wise decision to go clean-shaven after sporting a slightly foolish mustache during his army days (it would periodically reappear at the Bauhaus). His ears stuck out, but rather than detracting from his looks they only increased the impression that he was listening attentively. The perpetual look of mischief on his face made him all the more irresistible.

When Mahler went on a concert tour, leaving Alma at home, he barraged her as never before with telegrams and letters and sent a stream of presents and flowers. Alma thought he had stepped over the edge into madness. “The idolatrous love and worship which he shows me now can hardly be considered normal,” she wrote Gropius.24 Mahler became even more unbalanced when, after he returned to Alma in Vienna, he found himself repeatedly impotent.

The composer urgently sought a consultation with Sigmund Freud, and was upset to learn that Freud was on a family holiday in Leiden, in Holland. Alma’s cousin Richard Nepallek, a well-established nerve specialist, persuaded the inventor of psychoanalysis to see Mahler even during this time away from work. Freud consented under the condition that Mahler come to him. The composer took off on the long journey to Leiden.

Following an initial fifty-minute session in Freud’s hotel room, Freud and Mahler walked through the ancient city’s narrow streets for four more hours. Freud later described the encounter to both Marie Bonaparte and Theodor Reik, which is why we know a surprising amount about it. The great doctor made Mahler aware that he often called Alma by her rarely used second name, Marie. This was only one letter different from Mahler’s mother’s name, Maria. And while the composer was looking for elements of his mother in his wife, Alma was seeking a replacement father. According to Alma’s account of the one-day treatment, Freud told Mahler, “I know your wife. She loved her father and can seek and love only his type. Your age, which you are afraid of, is just what attracts your wife. Don’t worry about it.” Alma thought Freud was completely “right. … I really was always searching for the short, stocky, wise, superior man I had known and loved in my father.”25

The session with Freud succeeded in accomplishing one of its primary goals. Freud wrote Reik that Mahler’s understanding of “his love requirements” had enabled him to overcome “the withdrawal of his libido.”26

With Mahler transformed, Alma concluded that the lean and fit Gropius, four years her junior, had been her attempt to escape her natural attraction to her father’s type, and to compensate for Mahler’s sexual failings, which had now been cured. With that knowledge, she considered herself over her love affair and content in Toblach.

WALTER GROPIUS, HOWEVER, proved irresistible. Alma wrote asking him if he would support her having “a life of love” with him. While the revivified Mahler was composing with feverish zeal in their mountain retreat, Anna Moll helped Alma engineer a cover story so she could sneak off to Vienna to be with Gropius. Alma now had a theory that the affair was necessary for her health; she needed the intensity and frequency of her orgasms “for the heart and all the other organs.”27 She craved “not only the sensual lust, the lack of which has made me prematurely into a detached, resigned old woman, but also the continuous rest for my body.”28

Time apart from Gropius was unbearable. When she returned to Toblach, Alma wrote him, “When will there be the time when you lie naked next to me at night, when nothing can separate us any more except sleep?” She signed this letter “Your wife.”29

Two weeks later, she wrote “My Walter” that she wanted to bear his child. Again, she signed herself “Your wife.”30

WHEN ALMA ASKED WALTER whether he shared her desire for them to have a child while she was still married to Gustav, knowing that eventually the day would come when they might, “secure and composed, sink smiling and forever, into each other’s arms,” he responded by return mail, “I see a younger, more beautiful life arise from the pain endured.”31

He told her, “What we experience together is the highest, greatest thing that can happen to men’s souls.”32 Gropius thought in extremes and envisioned apogees. To bow to the rules and regulations that most people considered inevitable and irrefutable was anathema to the man who would change forever the nature of art education and design. The same faith in a new and wonderful future that he conveyed to Alma Mahler would inspire him to launch the Bauhaus. Conflict had to be overcome and battles won; in the relationship with his mistress, he developed the willpower and fortitude that he would need in Weimar.

But the obstacles did not go away. Gustav Mahler again fought to hold on to his wife. He was going to New York that fall to conduct the Metropolitan Opera, and he insisted that Alma and their daughter join him on the trip. Alma summoned Gropius to Munich, where Gustav was getting ready to conduct the premiere of his Eighth Symphony. The composer had dedicated the masterpiece to her, but she focused only on having every possible moment with Gropius before an ocean separated them.

The architect was equally avid. Day after day, he lurked impatiently at the entrance of his hotel, the Regina, waiting for Alma. The Mahlers were in another hotel nearby. Once Gustav left to rehearse, Alma rushed to the Regina, where they repaired to Gropius’s room for the few hours she had free. Alma always timed the encounters so that when the perpetually suspicious Mahler arrived back at their hotel, she was there waiting for him as if she had never left.

The premiere of the Eighth Symphony was an unmitigated triumph. Mahler’s only reaction to his success was to obsess over whether Alma was sufficiently pleased that her name was printed in the manuscript, while Alma obsessed over how much she wanted to have a child with Gropius.

The Mahlers would be sailing to America from Bordeaux toward the end of the third week of October. Alma was to take the Orient Express from Vienna to Paris four days ahead of Gustav. She instructed Gropius to get on the train in Munich, and to use the pseudonym Walter Grote when he bought his the ticket, in case the wary Gustav looked at the list of travelers. She would be waiting for him in the second sleeping car, in compartment number 13. When the train pulled into the station in Munich, Alma wore a veil so no one would recognize her through the train window. She sat nervously twisting a handkerchief inside her muff, hoping the encounter would come off without a hitch. When the compartment door slid open and Gropius appeared, she was in paradise. The bliss of that evening continued for four days in Paris; immediately afterward, Alma wrote Gropius, “Only a god could have made you. I want to take all your beauty into myself. Our two perfections together must create a demi-god.”33

ONCE IN NEW YORK, Alma Mahler demanded from Walter Gropius the fidelity she had good reason to think he might not offer. Almost as soon as her ship had docked in America, she wrote him: “Don’t squander your lovely youth, which belongs to me. … Keep yourself healthy for me. You know why.”34 Alma’s mother, still in Vienna, continued to encourage the affair. Anna Moll wrote Gropius that even though this was not the moment, she believed that the love between him and her daughter would “last beyond everything.” Frau Moll laid down the rules: “I have unlimited trust in you. …I am firmly convinced you like my child so much that you will do everything not to make her more unhappy.”35

Alma was mentally living in two worlds simultaneously. Gustav Mahler was in good form; even as she longed for Gropius, she enjoyed an American Christmas with her brilliant husband and their child. It was bliss to look out of the ninth-floor window at the Savoy Plaza Hotel and watch the elderly father and their six-year-old daughter walk through Central Park cheerfully throwing snow at each other. Then, suddenly, everything changed. Mahler developed a high fever from tonsillitis. He conducted at Carnegie Hall in spite of it, but soon the composer was so weak from a streptococcal infection that his wife had to feed him with a spoon. They immediately returned to Paris to see a bacteriologist in whom they had more faith than the American doctors. In France, as Gustav Mahler further deteriorated from the endocarditis that resulted from the infection, his wife began to sign letters to Gropius “Your Bride.” At the clinic where Mahler was being treated, in the Paris suburb of Neuilly, Alma wrote her lover from the room where she kept his picture hidden, imploring him to visit so she might feel his “warm, soft, dear hands.”36

The Mahlers and their entourage returned to Vienna. On May 18, Mahler received an emergency application of radium bags. Then, as Alma later recalled, “There was a smile on his lips and twice he said ‘Mozarte’ “—an affectionate diminutive of the great composer’s name.37 Alma watched her husband use a finger to conduct Mozart on the quilt until he suddenly stopped, his hero’s name still on his lips, and died at fifty-one. Alma noted what she considered an extraordinary coincidence: it was Walter Gropius’s birthday.

A few days later, Gropius wrote Alma about Gustav Mahler’s death. “As a human being he met me in such a noble way that the memory of those hours is inextinguishable in me.”38 That aplomb and tact would be crucial to Gropius’s effectiveness as the leader of the Bauhaus.

GROPIUS WENT TO VIENNA, where he and Alma were reunited in his room at the Hotel Kummer. She told Gropius that during the time she was in New York, she and Mahler had had sex whenever he wanted. Gropius, who had remained faithful to Alma during their separation, was furious. He could not bear the idea that Alma had been making love with Mahler regularly during all those months when she was acting as his nurse. That she had betrayed him with the dying man to whom she was married did not lessen the sting.

The next day, Gropius wrote Alma a letter from the Kummer: “One important question which you have to answer, please! When did you become his lover again for the first time? …My sense of chastity …is something overwhelming; my hair stands on end when I think of the unthinkable. I hate it for you and me, and I know that I shall remain faithful to you for years.”39 After he mailed the letter, he went back to Berlin—before she could answer.

As soon as Gropius arrived back in the German capital, he received a letter from Alma saying she was afraid she was pregnant and did not know what to do.

Mahler had been dead long enough that Gropius believed he was the father. He wrote her, “A feeling of shame is welling up in me …on account of my lack of mature precaution. … I … feel deeply saddened about myself.”40 Nonetheless, when Alma said she was coming to Berlin in September, he said he would not see her.

Then Alma discovered she was not pregnant after all. Liberated, she moved to Paris with her daughter. She begged Gropius to come to her.

This was one occasion when events so exhausted Walter Gropius that he could not function. He wrote Alma that the emotional turmoil of the previous month had left him too weak to travel; at the end of 1911 he checked into another sanatorium, the Weisser Hirsch, near Dresden. Informing his mother that “I know now how feeble I really am” and that he required a complete rest, he spent most of his time there walking in solitude.41

Alma Mahler continued to pursue Gropius for most of 1912. Feeling too wounded to respond, he left her letters unanswered until the end of the year, when he wrote her: “Everything has become basically different now. … I don’t know what will happen; it doesn’t depend on me. Everything is topsy-turvy, ice and sun, pearls and dirt, devils and angels.”42 That sense of life as the violent opposition of good and evil, with beauty vying to vanquish ugliness, would soon impel Walter Gropius to create and run the Bauhaus.

Oscar Kokoschka, The Tempest, 1913. Seeing this canvas in an exhibition, Gropius realized that his wife had another lover.

AT THE START OF 1913, Gropius went to the Berlin Secession exhibition. He was riveted by a painting by Oskar Kokoschka, who lived in Dresden. Kokoschka’s previous work had left him cold, but this time one picture grabbed his attention. The Tempest showed a man and a woman being tossed around in a boat on a stormy sea. It took a moment before Gropius realized who the couple was. The woman was Alma, “lying calmly, trustfully clinging to” Kokoschka, “who, despotic of face, radiating energy, calms the mountainous waves.”43 That description was subsequently provided by Alma, who recounted how Gropius deduced from the canvas not just that she and Kokoschka were lovers, but also that, when he looked at its date, Gropius realized that the couple had begun their affair while she was still telling him that he was the love of her life.

When Alma later wrote about the impact of this moment on Gropius, she made no effort to conceal her excitement. She had met the tall, lean Kokoschka in the winter of 1912. The starving artist in torn shoes and a frayed suit captivated her immediately. He was “handsome … but disturbingly coarse. … His eyes were somewhat aslant, which gave them a wary impression; but the eyes as such were beautiful. The mouth was large, with the lower lip and chin protruding.”44 She had gone to him to have her portrait done, and he had interrupted his sketching to sweep her into his arms. The following day, she received a letter saying, “I want you to save me until I can really be the man who does not drag you down but lifts you up. … If you, as a woman, will strengthen and help me escape from the confusion of my mind, the beauty that we worship beyond our power to know will bless us both with happiness.”45 Alma’s weakness for irregular-looking, emotionally overwrought men was even greater than her craving for the one who looked like a stage idol and was determined to exercise control.

After seeing that painting, Walter Gropius would wait more than a year before having any further communication with Alma Mahler. But he was far from through with her. Only when he was directing the Bauhaus would he grasp that her need to have tortured, brilliant lovers was chronic—and that he alone could not satisfy her.