In 1923, Johannes Itten resigned. For Gropius, this was a victory and a great relief. By then he had met the artist László Moholy-Nagy, whom he brought to the school to replace his rival. That same year, Josef Albers, a little-known art teacher and printmaker from Westphalia, was the first student to complete his Bauhaus course. He became a “young master,” and along with Moholy-Nagy and the painter Georg Muche began to teach the “Vorkurs.” Gropius’s power base was getting stronger.

During this period of internal change at the school, the Thuringian Legislative Assembly, known as the Landtag, insisted that Gropius organize a comprehensive exhibition to give evidence of what had been achieved in the four years since the Bauhaus had opened. He was against the idea, saying he needed more time if he was going to prove the success of his experiment, but the Landtag gave him no choice.

Once resigned to the necessity of the show, Gropius gave it his all. He wrote the authorities who had jurisdiction over any revisions to the former Academy of Fine Art to propose that he remodel its vestibule as the exhibition entrance. In this large, empty space, Gropius planned to install a rotating color wheel and a prism to illustrate color mixing and refraction. With Oskar Schlemmer in charge of execution, the old-fashioned light fixtures would be replaced with spheres and cubes, made of different types of glass—mirrored, frosted, milky, and opalescent—illuminated by colored light-bulbs. Gropius envisioned these radical changes as a diplomatic gesture that would “bridge the differences between the Academy and the Bauhaus by the interests we share” and would “demonstrate Goethe’s ideas on the correlation of art and science.”147

WALTER GROPIUS WENT ON the lecture circuit to raise money for the exhibition. On May 28, 1923, ten days after his fortieth birthday, he was in Hannover, giving his standard talk on “the unity of art, technology, and economy,” when his eyes fell upon two sisters sitting in the front row. One of them had the same sort of looks with which the young Greta Garbo would later captivate film audiences. She had Garbo’s thin lips, straight nose, large bright eyes, flawless skin, and piercing gaze. Gropius was bowled over; he felt he was giving his lecture to her alone, especially since, from the moment he began speaking, she stared at him with a visible attraction and responded as if his every word were changing her life.

A nephew of Gropius who lived in Hannover was able to tell him that the two sisters in the front row had the last name Frank; one was Ilse and the other Hertha. Gropius, however, had no way of identifying which was the one who had made him furious with himself for not having arranged to meet her after his lecture; he could not stop imagining how they would have spent the evening. His solution was to write a letter to both Frank sisters. He proposed a rendezvous when he passed through Hannover on his way home from Cologne a week later.

They agreed, and Gropius learned that the sister who had caught his eye was named Ilse. Twenty-six years old, she was the oldest of three girls whose parents had died years earlier. She worked in an avant-garde bookshop and was living with a man, both choices indicative of her fierce independence and strong willpower. Her lover was her cousin Hermann, whom she planned to marry that summer.

As usual, what someone else would have considered to be an insurmountable obstacle struck Gropius merely as a challenge. By June, Ilse Frank had become one more woman who succumbed to his charm. She wrote saying she knew how busy he was with the Bauhaus exhibition; regardless, she was desperate to be with him where he lived, and wanted him to know she would have four days off from the bookshop toward the end of the following week. He telegraphed back that she should spend all of them with him in Weimar.

FOLLOWING THOSE FOUR DAYS, Frank and Gropius began to organize further encounters. They also discussed marriage. She, however, had neither told Hermann about her lover nor canceled her wedding. The elaborate celebration planned for her aunt’s house in Munich was only a few days away.

Gropius wrote her, “I am not a man who can wait! I storm through life and whoever cannot keep pace will remain by the wayside. I want to create with my spirit and with my body; yes—also with my body; and life is short and needs to be grasped.” They had, he explained to Frank, “a holy bond” as a result of their “blessed nights” together. She needed to realize just how “hard and unrelenting” he was. His final entreaty was the same advice he gave students who were considering joining the Bauhaus: “Make a clean break, liberate yourself …I believe in you!”148

Ilse followed his bidding. She advised Hermann, and put a halt to the fast-approaching marriage festivities. At the same time, she shortened her name. By dropping the “l” and becoming Ise, which had a more modern, streamlined ring, the future Mrs. Gropius took on a new persona.

Walter and Ise Gropius shortly after their marriage on October 16, 1923. Following many tumultuous love affairs, the Bauhaus director briefly thought he had found stability

Gropius was reinvigorated. He wrote Ise, “My great work is now saved by you; you gave wings to my feet.”149 With that energy, he would make the Bauhaus exhibition, and the week of events that coincided with its opening, one of the most remarkable cultural events of the 1920s.

WALTER GROPIUS gave the Bauhaus exhibition the central theme of “Art and Technics, a New Unity.”

The young Herbert Bayer designed the boldly abstract announcement card that was the summons to the show. It utilized as few words as possible and was set in a new straightforward sans serif typeface. Alongside the text was a complete human profile—chin, mouth, nose, and forehead—made up of nothing more than three vertical rectangles and a single horizontal dash in a perfectly proportioned steplike arrangement. A square made the eye. Never before had a person’s visage been evoked in such engineer-perfect shorthand. The announcement assured that even in advance of the actual show one anticipated something unprecedented. It declared the joy of inventiveness, as did the postcards Bayer—as well as Klee, Kandinsky, Feininger, and other artists, each in his own vibrant style—made with the basic information and dates (see color plates 3 and 13). The excitement they generated was warranted. When the show opened on August 15, the former Weimar academy had been completely transformed.

Gropius had managed to find sufficient funding under nearly impossible conditions. Besides lecturing all over Germany, he had obtained support from family, friends, clients, and any business-people who had a few marks to spare. Money was so tight that the Bauhaus had had to let go of its janitors, but the masters’ wives scrubbed the floors, and everything was sparkling clean.

Entrance to the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition. Herbert Bayer’s graphics set the tone for the startling modernism of the show awaiting the public inside.

Visitors were greeted by powerful graphics over the entrance door. Theword “Ausstellung” (“Exhibition”) was written vertically in bold, squared-off lettering, white on a solid black vertical rectangle, with a brilliant white band adjacent to it: all designed by Bayer. This was the beginning of his role as one of the most influential graphic artists of the twentieth century. In America, after World War II, Bayer would be hired by Walter Paepecke, who founded the Aspen Skiing Company and Aspen Institute in Colorado. There the Bauhaus-trained artist would make posters promoting winter sports and become known all over the world. He also created many other well-known graphics and logos.

He would keep silent, however, about his work for the Nazi Party. In 1936, Bayer designed a brochure that extolled the glories of life in the Third Reich and of Hitler’s impact, and that accompanied an exhibition for tourists visiting the Berlin Olympics. The brochure was conceived to advertise Hitler’s achievements at a time when skepticism about the Third Reich was growing following Germany’s invasion of the demilitarized Rhineland. Bayer’s brochure included the Heinkel airplane factory, designed by Gropius’s former associate Herbert Rimpl; the building combined Bauhaus modernism with references to traditional architecture in the cottagelike workers’ houses. Throughout the brochure, Bayer linked the old and the new to advertise Germany as a holiday destination. Later in life, when asked about it, Bayer would discuss only its use of duotone technique and other formal elements. Nevertheless, his involvement in Nazi propaganda would color many people’s vision of the Bauhaus.

AFTER BEING WELCOMED by Bayer’s signage, the public entered a vestibule filled with different colors of light and saw the extraordinary achievements of the four years since the school had opened its doors. The new art triumphed on every surface and in every open space. There wasn’t a single alcove, staircase, or classroom that was not put to use to show murals, reliefs, and design work. Each workshop presented the products that had been developed there, and the classrooms were used to display theoretical studies and materials from the preliminary course.

The nearby State Museum of Weimar was turned over to an exhibition of Bauhaus painting and sculpture; it included many works that would eventually be ranked as masterpieces of modernism but that were at the time simply “faculty work.” And a model house, the “Haus am Horn,” had been constructed in the neighborhood where many faculty members lived. It had been built as an exemplar of Bauhaus style and was furnished entirely with products of the school’s workshops.

The work on view throughout the main building and in the museum show extolled straight lines, right angles, and perfect circles, clean and pure, in a profusion never seen before. The geometric shapes glistened in chrome in lamps and tea balls and serving vessels, and pulsed in vibrant yellows and reds and blues in paintings so rhythmic as to seem audible. Oils and watercolors by Paul Klee presented his unique visions of birds and stars and other natural forms in abundance. Wassily Kandinsky’s canvases combined intellectual rigor and spiritual mystery. The art was immensely varied, yet it was linked by its consuming energy, its look of faith, and its pioneering use of abstract form.

The display of the weaving workshop included some hangings that were the textile equivalent of oil paintings. These singular objects, mounted on the wall, serving no practical purpose, were revolutionary in their brazen simplicity. In addition, there were swatches of materials to be fabricated industrially and used as draperies, upholstery, and carpeting. Remarkable for their absence of floral or botanical subject matter, the new textiles celebrated raw materials. Twine, silk, hemp, and even metallic thread were interlaced in interesting ways, serving as the source of aesthetic delight as well as practical effectiveness.

The work on the wall that stood out above all the others was an austere, minimalist composition by the woman I came to know as Anni Albers. Annelise Fleischmann, as she was at the time, was a rich young woman—her mother’s family, the Ullsteins, were Europe’s most prominent publishing family—who had arrived from Berlin the previous year. This quiet twenty-three-year-old, as socially timid as she was bold in her art, was not known to many people. She had not even wanted to join the weaving workshop and initially had hoped for carpentry or wall painting, thinking textiles to be “too sissy,” the equivalent of needlepoint. But weaving was where most, although not all, women went, and Fleischmann suffered from a physical disability that, while she never acknowledged or discussed it, made certain Bauhaus tasks impossible for her. Now, even if working in thread was not her first choice, she had done something unprecedented. A few gray, black, and white rectangular blocks and bands made a bold new sort of visual art. Fleischmann’s piece encouraged meditation; its gravity mixed with an evident lightness of touch gave it an intoxicating power associated more with music than with the visual arts. While most of the products of the weaving workshop were suitable for commercial production, advancing Gropius’s goal of design for industry, this one-off suggested that craft and art could be the same thing. (See color plate 24.)

In the glass workshop, Josef Albers—the artist Fleischmann would ultimately marry—also revealed new possibilities for right angles and solid blocks of color. A young man from a very different background—she was Jewish; he was Catholic, the son of a carpenter/electrician/plumber/jack-of-all-trades in the smoky industrial Ruhr Valley—Albers, who was thirty-two when he arrived at the Bauhaus in 1920, and who until then had been a schoolteacher in his hometown, was so penniless that, in order to get funding to attend the Bauhaus, he had had to promise the regional teaching authorities back in Westphalia that he would return after his time in Weimar so that they could reap the direct benefits of what they had sponsored. At first, because Albers lacked sufficient funds for art supplies, he had spent a lot of time at the Weimar city dump hacking up bottle fragments and other detritus with a pickax to use in his glass assemblages. These vibrant and playful objects that were on view in the 1923 show gave spiritual power to junk; so did a carefully conceived, leaded stained-glass window in which checkerboard patterns counterbalanced large squares, pink rectangles sparkled with small white squares inside them, suggesting openings, and lattice patterns played against broad expanses of gray, purple, and deep red. In keeping with the tenets of the Bauhaus, Albers’s work could be used in buildings—he had already done some large windows for Gropius’s Sommerfeld House—but, like Fleischmann’s weaving, it triumphed as pure art, as independent of practical purpose as a Renaissance Madonna.

There was also an exhibition of recent architecture being done all over the world. This included seven illustrations by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier showing his proposed city for three million inhabitants. This innovative if shocking scheme, intended for Paris, represented a new form of urbanism that required razing entire neighborhoods in order to build skyscrapers that would be spaced around large open areas to allow access to the sky and would be linked by an efficient transportation system.

Like the displays in the school, the show of paintings at the Weimar Museum was evidence of a revolution. The work unabashedly celebrated beauty in places where it had not previously been recognized. Lyonel Feininger’s cityscapes imbued tough urban forms—train viaducts, narrow streets, the spaces between anonymous warehouse buildings—with charm and lightness, refracting their shapes as if through a prism. Kandinsky’s abstractions were orchestrated of pure circular forms orbiting around one another, straight lines flying off, and waves and zigzags moving to and fro, all in an intentional cacophony of colors; these unusual canvases exploded with energy: they were as powerful as atomic fusion and at the same time delicate and graceful. Klee’s images of opera singers, underwater gardens, and purely imaginary architectural mélanges were somewhere between the known world and a dreamlike fantasy, deft and professional in execution while childlike in spirit. László Moholy-Nagy’s precise paintings of overlapping geometric forms and his sculptures of shimmering nickel, steel, chrome, and copper all appeared to move at breakneck speed. Oskar Schlemmer’s rendering of human forms, both painted and sculpted, reduced the body to a combination of abstract shapes, making it seem very much of the future while simultaneously imbuing it with the nobility and panache of the knights of ancient legends.

Not everything was of equal caliber, however. Even though Johannes Itten had recently left the Bauhaus, his work was a major element in this show; his paintings of awkwardly formed, robotic, puffed-up children, with the artist’s name painted in large letters on a scrolling ribbon overhead (contradicting the Bauhaus ideal of artistic anonymity), were clumsy as well as cloying. Gerhardt Marcks’s sculptures of mothers and babies, though sweet, lacked the artistic merit that would have been needed to make their sentimentality effective. Georg Muche’s interior scenes were competent exercises in a late cubist style, but there was nothing exceptional about them; likewise, Lothar Schreyer’s figures seemed to be the art of a follower rather than of a truly original talent. The Bauhaus tried to present itself as a community, but there was no way of getting around the reality that it had greater and lesser lights.

THE UNUSUAL OBJECTS MADE as studies for the Vorkurs resemble the products that would be commonplace in children’s art classes seventy years later. But in the early 1920s, those who did not grasp their revolutionary intention considered them outrageous. There were towers of tin cans receding in size, with metal bands and wires wrapped around them, and mixtures of straw, wood shavings, and brush. There were also patchwork collages of fabrics, wallpaper samples with buttons on them, and drawings that showed the structure of wood or demonstrated color mixing. These myriad objects were all evidence of a desire to look at the essence of things, to understand materials and optics, and to explore the nature of construction.

The carpentry workshop featured severely geometric children’s toys cut out of wood and lacquered in bright colors. There was also a baby’s cradle that prompted some of the good people of Weimar to accuse the Bauhaus of promoting child abuse. Made with two tubular steel wheel shapes joined at the bottom by a rod of the same material to create the base for two wooden planks, opening at angles and joined as if at the point of a triangle to form the baby’s bed, this more than any other object would attract the ire of the Bauhaus’s opponents, who did not make the claim of cruelty in jest. But most of the furniture, however unusual, inspired less controversy. Marcel Breuer and Eric Dieckmann had pared down the structure of beds, tables, and chairs so that they were as simple and honest as possible, without an iota of decoration. The same Josef Albers whose pieces were in the glass workshop had made a conference table and shelves in which smooth planks of contrasting woods were arranged rhythmically, imbuing the efficient and practical with an unprecedented jazziness.

The pottery workshop showed cocoa pots and canisters and coffee sets intended for mass production. Of timeless simplicity, these vessels offered proof that Bauhaus modernism had a leanness that, even in its novel expression, was connected directly to human need in a way that was universal and dated back to the birth of civilization.

The glistening, fantastically simple objects in the metal workshop were especially eye-catching. Dynamic lamps, ashtrays, and pitchers had been made by the innovative Marianne Brandt, one of the few women who had found a venue other than weaving. A desk lamp designed by K. Jucker and W. Wagenfeld featured a spherical glass base, a tubular glass shaft, a half globe of milk glass as its shade, and wiring contained in a silver tube inside the glass one. It represented a courageous new design approach, and although no one could have anticipated it, it would in time become a modern classic. From the versatile Josef Albers came fruit bowls made from nothing more than three wooden balls as the feet, a sphere of clear glass as the base, and a metal rim to keep the fruit in place. It was a rare use of frankly industrial forms for a domestic container.

The wall painting at the Bauhaus was another remarkable element of that 1923 show. From floor to ceiling there were spheres and rippling waves and bold sequences of smokestack-like columns. This decoration incorporated the utilitarian radiators as if they were design elements rather than something to be avoided. That acknowledgment of what a previous generation would have covered up embodied the spirit of the Bauhaus: honesty about what is needed in life, and the promulgation of the idea that anything can be made part of a total visual symphony. The hiding of reality and concealment of the functional that for centuries had been common practice in design for the middle and upper classes was toppled. And the need for gratuitous decoration referring to the natural world was made irrelevant by the rich possibilities of pure abstraction.

THE HAUS AM HORN was a square within a square. The large central square was the living room; almost one and a half times as high as the rest of the structure, it let light in through clerestory windows. The lower structure that enveloped it contained a well-equipped kitchen, a dining room, separate master bedrooms for the husband and wife, a room for the children, bathrooms, and storage spaces. The details put to the test the idea of incorporating into everyday living a lot of the breakthrough concepts on view in the Bauhaus exhibition. The cabinets, beds, desks, and chairs were all constructed without adornment. There was no window trim, and the radiators were exposed, as were the drainpipes. The message was one of total honesty, although to many viewers it also conveyed unforgiving coldness.

The Haus am Horn was designed by Georg Muche, but since Muche was a painter, not an architect, Gropius, as well as Adolf Meyer, had worked on many of the technical details. Gropius, as usual, was the one who articulated the objectives of the project for the general public. He declared that the Haus am Horn would provide “the greatest comfort with the greatest economy by the application of the best craftsmanship and the best distribution of space in form, size, and articulation.”150

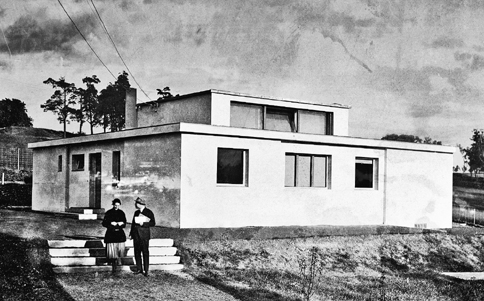

Haus am Horn, Weimar, 1923. Inside and out, this unusual dwelling embodied a new aesthetic.

Gropius had also procured the financing—from Adolf Sommerfeld, the Berlin lumber merchant for whom he had built a very different sort of house a few years earlier. Sommerfeld’s own house was sheathed in logs. While aspects of it bore the imprint of modernism, it fit in with the grand country-house style one expected for a rich man’s private residence. The wealthy merchant would never have lived in anything like the Haus am Horn, which was made of steel and concrete. But he was the sort of patron willing to pay for work that had no connection to his personal taste.

The reigning force at Haus am Horn was practicality. Gropius declared, “In each room, function is important. … Each room has its definite character which suits its purpose.”151 The furniture and cabinetry, much of it made by Marcel Breuer, who was still a student, used unadorned planks and slabs of lemonwood and walnut, everything pared down and minimal, so that even the knobs were utterly plain and round, matched to the cabinets and drawers they were used to open. What might otherwise have seemed stark or antiseptic was animated by a rhythmic juxtaposition of forms and playfulness in the use of light and dark woods. Light fixtures designed by Moholy-Nagy and made in the metal workshop further energized the rooms. Even if the house looked like a barrack from the outside, the inside had an esprit and cheerfulness that made clear that Bauhaus design enhanced pleasure in everyday living.

Gropius’s uphill battle to garner public approval for the school was beginning to pay off; the Landtag had done well to insist on the exhibition. Dr. Edwin Redslob, the national art director of Germany, made a public statement declaring that the Haus am Horn would have “far-reaching cultural and economic consequences.” Redslob was the rare government official who had the foresight to see the worth of the Bauhaus at a time when so many of his colleagues perceived it as a threat. His endorsement was a lifeline. It helped the school retain its governmental support and a degree of financial security. It mattered greatly that this national figure commended this new domestic design, “which organically unites several small rooms around a large one,” as “bringing about a complete change in form as well as in manner of living. … The plight in which we find ourselves as a nation necessitates our being the first of all nations to solve the new problem of building. These plans clearly go far toward blazing a new trail.”152

THE EXHIBITION THAT GROPIUS had hoped to postpone managed, at least for a brief period, to enhance the luster of the Bauhaus nationally and even internationally. This was in part because of Bauhaus Week, a program of activities he organized that also began on August 15. Events included lectures by Gropius on the unity of art and industry, by Kandinsky on synthetic art, and by the Dutch architect J. J. P. Oud on recent advances in building design in Holland. Hindemith and Stravinsky both appeared in Weimar for performances of their work. That one lively week in summertime was euphoric from start to finish. There was a festival at which a fantastic array of paper lanterns were strung overhead, and a fireworks performance where the vibrant explosions were yet another form of impeccably crafted abstraction. A light show made incorporeal glows the essence of art. The Bauhaus jazz band performed its intensely animated music at a dance, and Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, which he had developed more than a decade earlier, was given a stellar production. Those who saw it at the Bauhaus would never forget its mix of playfulness and profundity or its simultaneous activation of all the senses.

From the moment the ballet began, the extraordinary figures against brilliant abstract backdrops appeared to be working their way toward a dramatic climax. Wordless gestures, musical progression, and changes in scenery conveyed a feeling of expectation. Two males and one female danced twelve scenes in eighteen different costumes made of rigid, vibrantly colored papier-mâché. Sometimes encased in a metallic coating, the costumes gave the impression that the human body was composed of symmetrical geometric forms. The male outfits included one made of pointed ovoids like teardrops, another of puffy striped trousers formed like those of the Michelin tire man. The woman changed from a skirt like stacked soccer balls to one like an open Chinese parasol to a tutu that resembled a reversed champagne coupe. In the first act, these unusually shaped humanoids flounced around gaily in a burlesque against a lemon-yellow set. In act two, they became more deliberately organized, enacting a festive ritual in a setting that was entirely pink. Finally, in the third act, they performed on an all-black stage, becoming dreamlike characters of the night. The fantastic trio had taken the enraptured audience from a lively bounce to a consuming ambiguity and mysteriousness.

WHAT GROPIUS HAD MANAGED to achieve in just four years in Weimar becomes apparent in the 1936 autobiography of Igor Stravinsky. Rather than write a full account of his life to date, the forty-three-year-old composer deliberately recalled the few selected events that he considered the most significant of all his experiences. Stravinsky writes that he had been invited to Weimar in August 1923 as part of the program that accompanied the “very fine exhibition” there.153 His Histoire du Soldat was to be performed during Bauhaus Week; it had been previously presented on only one other occasion, in Frankfurt, at a concert of modern music organized a few months earlier by Paul Hindemith.

The journey Stravinsky and his future wife, Vera, endured to get to Weimar was harrowing—typical of what one could expect in Germany in those years. Although Stravinsky was married to his cousin, Katerina Nossenko, whom he had known ever since they were young children, he had recently met Vera de Bosset, who was married to the painter and stage designer Serge Sudeikin, and while Stravinsky makes no mention of Vera’s presence on the trip (he remained married to Katerina until her death in 1939, only marrying Vera the following year), we know she was with him because of a reference to the journey to Weimar in her diary. On this first major outing together, the illicit couple started out from Paris on August 15 for Stravinsky’s performance on August 19. He could only get train tickets to Griesheim, a village near Frankfurt that was on the demarcation line of the part of the Rhineland then controlled by the French, who had reoccupied the Ruhr and the Rhineland the previous January. The rail station in the village was manned by African soldiers, who faced Stravinsky with fixed bayonets. They told him that it was too late at night for him and Vera to reach Frankfurt itself, or even to get a phone call through, and that they would have to stay in the crowded waiting room.

Stravinsky, who was used to first-class hotels, immediately set out to look for any sort of hostelry where they would at least have a bed. The soldiers stopped him with the warning that he might be mistaken “for a vagrant” and shot. The composer had no choice but to stay squeezed between other people on a bench, “counting the hours till dawn.”154 At 7 a.m., a child guided him and Vera through soaking rain to the tram, which took them to Frankfurt’s central station so they could continue to Weimar.

The trip was worth the effort. The way the members of the Bauhaus appreciated Soldat was one of the joys of the composer’s life. Here were people for whom the marvelous energy and playfulness of that great work, its feeling of insouciance mixed with gravitas, corresponded completely with their own interests. Not only that, but Stravinsky met Ferruccio Busoni, a composer he greatly admired but who, Stravinsky had been told, was “an irreconcilable opponent of my music.”155 Stravinsky considered Busoni “a very great musician” and was therefore delighted when he and Vera sat with Busoni and his wife, Gerda, at the performance of Soldat at the National Theater in Weimar—Gropius had organized the most important concerts there—and observed Busoni enjoying Soldat. Both Busonis, Stravinsky would tell Ernest Ansermet, “wept hot tears …so moved were they by the performance.”156

After the performance, Busoni, in spite of his fundamental opposition to work like Stravinsky’s, commented, “One had become a child again. One forgot music and literature, one was simply moved. There’s something which achieved its aim. But let us take care not to imitate it!”157 Because Stravinsky had never before met Busoni, and would never do so again—the Italian composer died the following year—that experience became fixed in Stravinsky’s memory as a key element of his visit to the Bauhaus.

The following night, the Stravinskys had dinner and spent the evening with Wassily and Nina Kandinsky, and with Hermann Scherchen, who had conducted Soldat. Sixteen years later, Scherchen’s role in that performance would be held against him by the Nazis, but in 1923 the atmosphere was euphoric.

NOT EVERYONE APPROVED of the Bauhaus exhibition, the Haus am Horn, or the events of Bauhaus Week. The Bauhaus had its loyalists in high places, especially Redslob, but there was vehement opposition to it all over Germany. Newspaper headlines of the period included “The Collapse of Weimar Art,” “Staatliche Rubbish,” “Swindle-Propaganda,” and “The Menace of Weimar.”

The main issue was that an unknowing press and public assumed that because Gropius had started the school under a socialist regime—the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar had been politically to the left—the Bauhaus was a hotbed of radical politics. Since Gropius knew that ignorant observers would think as much, he had prohibited political activity there, but as the local government became increasingly rightist, the hatred mounted.

The situation became so bad that the school’s business manager ended up writing Gropius that “the attitude shown by superior officials is malevolent, obtuse, and so inflexible as constantly to endanger the growth of the institution.” He warned that the “open animosity” of the latest government was threatening the school’s survival. Even in the artistic community, where one might have hoped for more enlighted attitudes, there were prominent people who saw no reason for the Bauhaus to exist. Karel Teige, a well-regarded critic and artist who was a leading figure in the Czech avant-garde, writing in Stavba (Building), the most important architectural periodical in Czechoslovakia, asked, “If Gropius wants his school to fight against dilettantism in the arts, … why does he suppose a knowledge of the crafts to be essential for industrial manufacture?” Teige was typical of many influential naysayers in his view that “craftsmanship and industry have a fundamentally different approach. … Today, the crafts are nothing but a luxury, supported by the bourgeoisie with their individualism and snobbery and their purely decorative point of view. Like any other art school, the Bauhaus is incapable of improving industrial production.” Teige questioned every major premise of Bauhaus education, declaring, “The architects at the Bauhaus propose to paint mural compositions on the walls of their rooms, but a wall is not a picture and a pictorial composition is no solution to the problems of space.”158 On the other hand, the distinguished Swiss architecture historian Siegfried Giedion, in an article for the Zurich newspaper Das Werk, wrote—in September 1923, while the exhibition was still on though Bauhaus Week was over—”The Bauhaus at Weimar …is assured of respect. … It pursues with unusual energy the search for the new principles which will have to be found if ever the creative urge in humanity is to be reconciled with industrial methods of production.” Giedion made his readers aware of the difficult situation of this noble cause: “The Bauhaus is conducting this search with scant support in an impoverished Germany, hampered by the cheap derision and malicious attacks of the reactionaries, and even by personal differences within its own group.” He commended Gropius’s institution for “reviving art” and tearing down “the barriers between individual arts” as well as recognizing and emphasizing “the common root of all the arts.”159 To those with open eyes and open minds, what was taking place in Weimar was a miracle.