In spite of all the internecine battles that had occurred in the five years of the Bauhaus’s existence, a few individuals were determined to keep the school going. The benefits to a community of people with similar goals were vast.

The perspicacious Ludwig Grote, director of the Gemaldegalerie in Dessau, informed Fritz Hesse, Dessau’s mayor, of the immeasurable significance of the Bauhaus, and suggested it might relocate there. The lively modern art school in Frankfurt am Main took a strong interest in incorporating the Bauhaus into its existing structure.

In the midst of all this turmoil, in late January 1925, Gropius took off with Ise for a four-week vacation. No one could even reach him. The isolation and complete change after years of struggle gave him the perspective he needed. By March, Gropius was among those investigating conditions in Dessau. In a short time “Das Bauhaus in Dessau” was official, with “direction: Walter Gropius” underneath the new name.

Located at the junction of the Elbe and Mulde rivers in the duchy of Anhal, Dessau was a small city surrounded by arid land. It lacked the charms and auspicious history of Weimar, but it did have an important theater built in the eighteenth century, and Wagner, Paganini, and Liszt had all performed there. The city had thrived during the industrial revolution and had a feeling of energy without being especially cosmopolitan. Now, by appointing Walter Gropius director of the existing School of Arts and Crafts and trade school, and folding the entire Bauhaus staff into those institutions, the Municipal Council was taking major steps to give Dessau a different aura. What they did out of civic loyalty saved the Bauhaus. The great enterprise that had been stopped in its tracks in Weimar would be able to continue to provide innovative experiential education and to be a haven for some of the world’s leading creative geniuses.

As usual, Gropius’s iron will made all the difference. The Municipal Council had envisioned the Bauhaus in an ancillary role to the School of Arts and Crafts and the trade school already in operation. But, as his lovers and students knew, with Gropius it was all or nothing. He quickly persuaded council members to let him design new buildings for the Bauhaus, on a splendid site about two kilometers from the city center. As soon as he had their consent, Gropius opened a new architectural office in Dessau and began.

By the end of the summer, Gropius had completed working drawings for the new building. To achieve this, he employed some of his former students, among them Marcel Breuer. The building complex that emerged from their charette was marvelously functional, and of unprecedented appearance. A sparkling white, crisp amalgam of interlocking geometric forms, with a neatly tapered bridge and a flurry of balconies breaking up the strong masses, it was bold and refined at the same time, radiating power and optimism and a love of beauty.

The structure housed spacious workshops, a large auditorium, a dining hall, and residential facilities. By the time it opened in April 1926, it was the twentieth-century equivalent of a medieval village, a place for working and living in a community—even though the object of adulation was now art and design rather than the God for whom the Gothic cathedral had been built. The Dessau Bauhaus was a perfect marriage of function and style; it used industrial devices to achieve artistic grace and coupled high tech with poetry. Its glass walls were tensile light, its flat roof a statement of newness.

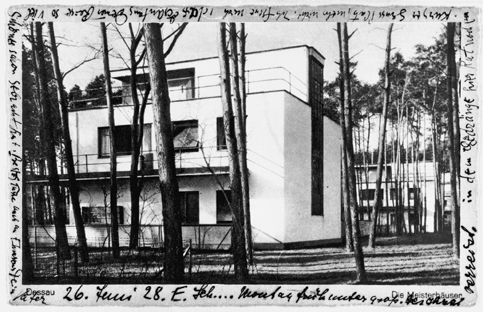

The Bauhaus in Dessau, built by Gropius, 1926, in a photo annotated by Josef Albers. The building separated the living accommodations from the work and community spaces, while linking them with a bridge.

Even today, the building is the symbol of all that was achieved within it. While he was designing it, Gropius carried on his campaign to reinvigorate the Bauhaus and to organize its students and faculty, but nothing was more effective as a gathering cry and an icon of the new faith, a representation of vigor, than this handsome shell with its impeccably clean, bold vertical lettering saying simply “Bauhaus.”

AS BEFORE, Gropius was the school’s main public spokesman, codifying its philosophy with serenity and assurance. Impressively resolute, as elegant in his verbal expression as in his architecture and his personal appearance, he reiterated that whether one was creating “a container, a chair, or a house—one must first of all study its nature; for it must serve its purpose perfectly, that is, it must fulfill its function usefully, be durable, economical, and beautiful.”171

Gropius intended for the Dessau Bauhaus to improve life for the masses; even more than its Weimar predecessor, it was to penetrate society at every level, and to do so while emphasizing superior quality: “The Bauhaus fights against the cheap substitute, inferior workmanship, and the dilettantism of the handicrafts, for a new standard of quality work.” The goal was “simplicity in multiplicity, economical utilization of space, material, time, and money.”172

Gropius’s ability to deal with difficult people was again called upon. Money was tight, in spite of the generosity of the Municipal Council, and he decided he had no choice but to ask senior faculty to give up 10 percent of their teaching salaries for the first year in the new location. Klee refused. Gropius, in turn, wrote an extremely measured response. He explained the harsh realities of the overall financial situation and of the antipathy toward Bauhaus modernism, and politely beseeched Klee to recognize the efforts that the mayor of Dessau and Gropius himself had made to ensure that Klee would enjoy ideal working conditions. As insistent as he was in matters of love, Gropius was willing to go down on his knees to beg for what he wanted. He wrote, “I simply cannot believe that you, dear Herr Klee, will desert me in this matter, and I cordially request you to support me.”173 In this instance, however, Gropius failed to persuade: neither Klee nor Kandinsky would agree to the cut.

In spite of the grim financial situation, Mayor Hesse provided land and funding for private houses for the Bauhaus masters. There was a forest of pine trees on Burgkuhnauer Allee, only a kilometer from the main Bauhaus building. It was a wonderfully bucolic setting, ideal for these artists who were as interested in the truths and tranquillity to be derived from nature as they were in modernism. Gropius immediately designed idyllic dwellings for the school’s upper echelons.

Wassily and Nina Kandinsky, Georg Muche, Paul Klee, and Walter Gropius at the Dessau Bauhaus, 1926. At first, the Bauhauslers had been sceptical about moving to Dessau, but the new headquarters and masters’ houses soon provided them with exceptional working and living conditions.

While the Bauhaus masters all belonged to the same purposeful brigade and shared certain ideals and some beliefs, they still had their strong individual preferences and quirks. Gropius, aided by Ise, set out to be as accommodating as possible with regard to their new houses. The masters’ wives had very specific requests. Tut Schlemmer wanted a gas stove, while Lily Klee preferred one fueled by coal. Georg Muche’s wife, the Norwegian painter Erika Brandt, insisted on a new electric model. Nina Kandinsky, ever nostalgic for her native Russia, wanted only a Kamin—a wood-burning stove made of heavily ornamented black iron, which looked more suitable for a cozy dacha than a contemporary kitchen. For themselves, Ise and Walter Gropius picked streamlined furniture and objects from the Bauhaus workshops, or designed their own suitably modern pieces, but everyone else had tastes that had little to do with the school’s program.

While their houses were under construction, the masters lived in whatever apartments they could rent. Neither the new building nor the residences were ready when the Bauhaus reopened in Dessau in October 1925.

Postcard sent by Lily, Felix, and Paul Klee in 1928. It shows a photo taken by Lucia Moholy-Nagy of the masters’ houses in Dessau, where the Klees and Kandinskys lived in more idyllic working conditions than they had ever known before.

The workshops and classrooms were located temporarily in a defunct textile mill and an unheated building that had been a rope factory.

In these makeshift facilities, Gropius reiterated the institution’s ideals with his usual fervor, and reminded people of the links he was forging between the workshops and German industry. Inconveniences were of secondary importance.

The pace was relentless that summer as he tried to whip the new building into shape and organize the reborn institution. In August, Ise, who was pregnant, had an emergency appendectomy during which she lost her baby. But Gropius could not afford to stop. He lectured wherever he thought he could drum up support, while also working on his architectural projects and promoting prefabricated housing. He now undertook the publication of a series of Bauhaus book, for which he functioned as editor in chief Privately he was working on office buildings and an important project for the great exhibition of modern housing that was scheduled to open in 1927 in the Weissenhof section of Stuttgart. He was dealing nonstop with personnel issues, too; when Georg Muche wanted to switch from being form master of the weaving workshop to the architectural workshop and Gropius didn’t think he was up to the task, it was Gropius who had to make the decision and enforce it diplomatically. Walter Gropius’s ability to be architect, educator, and administrator at once was the backbone of the school.