Paul Klee specified the text for his tombstone:

I CANNOT BE GRASPED IN THE HERE AND NOW

FOR I LIVE JUST AS WELL WITH THE DEAD

AS WITH THE UNBORN

SOMEWHAT CLOSER TO THE HEART

OF CREATION THAN USUAL

BUT FAR FROM CLOSE ENOUGH1

By the time he arrived at the Weimar Bauhaus at the end of 1920, this totally original, free-spirited artist had demonstrated just how close to the heart of creation he was. A profusion of watercolors and oils in which plants burst into flower, and the seas and heavens explode into life before our eyes, are like moments of birth.

With his extraordinary mind occupying that realm in which life is generated, in his daily life Klee inhabited territory distant from the usual stage of human conduct. When Anni Albers, who was first his student and then his neighbor, said that Klee was like “St. Christopher carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders,” it was both because he was in his own orbit and because he was preoccupied with his task of making art.

Will Grohmann, an astute art historian who often visited the Bauhaus, writes that the reticent Klee “held the world at arm’s length.”2 Neither at meetings of Bauhaus masters nor on the rare occasions when he had ordinary conversations did he ever commit himself to strong opinions about how people should act.

The painter Jankel Adler describes what Klee looked like from afar:

I have often seen Klee’s window from the street, with his pale oval face, like a large egg, and his open eyes pressed to the windowpane. From the street he looked like a spirit. Perhaps he was trying to decipher the language of the branches across his Windows.3

Adler gives a picture of Klee at work:

He used to gaze for a long time at his prepared canvas before he began the drawing. …I have never seen a man who had such creative quiet. It radiated from him as from the sun. His face was that of a man who knows about day and night, sky and sea and air. He did not speak about these things. He had no tongue to tell of them. Our language is too little to say these things. And so he had to find a Sign, a color, or a form. … Klee, when beginning a picture, had the excitement of a Columbus moving to the discovery of a new continent. He had a frightened presentiment, just a vague sense of the right course. But when the picture was fixed and still he saw that he had come the true way he was happy. Klee, too, set out to discover a new land.4

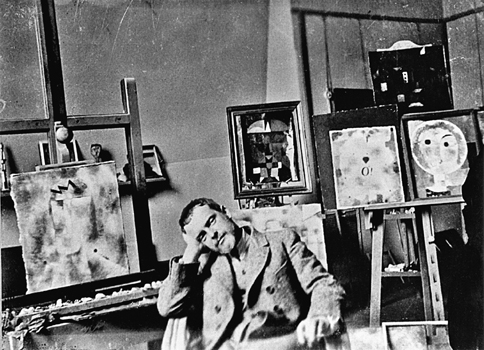

Paul Klee in his studio at the Weimar Bauhaus, 1922. Klee worked on many paintings simultaneously.

KLEE’S NATURE AND COMPORTMENT are evoked by Dostoyevsky’s description of the remarkable Prince Myshkin, hero of The Idiot: “For a long time he seemed not to understand the turmoil that was seething around him, or rather, he understood completely and saw everything, but stood like a man isolated, not taking part in any of it, who, like the invisible man in a fairytale, has made his way into the room and was observing people who had nothing to do with him, but who interested him.”5 This man of few words and consistently calm demeanor was often seen walking alone in Weimar, absorbing nature in solitude. If he separated himself from the quotidian lives of those around him, he responded deeply to the pulse of life within every bird or flower. The lusty appreciation and unguarded enthusiasm that emerged in his copious artistic production echo Myshkin’s encomium for life: “You know, I cannot understand how one can walk past a tree and not be happy that one’s seeing it? …How many things there are, at every step, so lovely that even the man at his wit’s end will find them lovely! Look at a child, look at God’s dawn, look at the grass growing, look into the eyes that look back at you and love you.”6

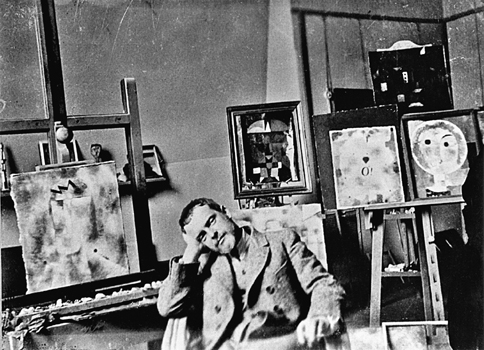

Photograph of Paul Klee taken by his son, Felix, at their house in Weimar on April 1, 1925. Most people found it hard to fathom what was going on in Klee’s mind.

For Klee, artistic creativity was steered by the same mysterious force by which the universe came into being and all life begins. One of his favorite words, in his teaching at the Bauhaus as in the texts he wrote when he was there, was “genesis.” He lived at the miraculous moment of everything emerging for the first time.