What today we call gender issues were not openly discussed at the Bauhaus. Active as people were, they did not talk a lot about sex. Klee, however, addressed through his art, with spectacular ease and openness, aspects of maleness and femaleness. He did so lightly and wittily, yet he brazenly depicted sexual instincts, in all their inherent complexity, without any inhibition.

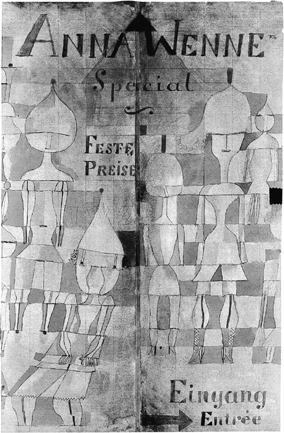

Klee’s Window Display for Lingerie invokes, in a way both worldly and carefree, sophisticated and childlike, a plethora of issues about male and female traits within a single human being. Four large figures either melt from or emerge into a shimmering, amorphous mosaic pattern. Some smaller figures, and parts of figures cut off by the picture’s right and left edges, suggest that there is a whole crowd out there of which we are seeing only part. Some of these characters sport stiletto-heeled boots and outfits that are like flared knee-length shorts or culottes; with their muscular legs and hourglass figures, they might be transvestites. They are not exactly androgynous because, rather than seeming like masculine women or feminine men, they are, alternately, very girlish or very soldierlike; instead of combining genders, they appear to flip back and forth between them. Their headgear might be helmets, large teardrops, or dunce caps. Several of the jaunty gnomelike creatures stand boldly; others look as if they are recoiling under attack.

The words Klee has painted on the picture surface add to the incomprehensibility. They look like lettering on glass with the personages being part of a shopwindow display; this reading of the scene, the most evident one, would be even more logical were it not for the abstracted mountain peak behind these creatures who resemble marionettes as much as mannequins. The lettering at the top says “Anna Wenne Special.” The assumption we might make today, at a remove from the Weimar culture of the 1920s, is that Anna Wenne was either the brand name of a familiar product or a well-known actress. If so, the words “Feste Preise” (fixed prices) would perhaps make sense underneath the word “Special,” for which the crown on one of the ambiguous pieces of headgear serves as an exclamation point. And presumably the words “Eingang / Entrée” (“Entrance” in both German and, in smaller letters, French), with the accompanying arrow, would also make sense because, knowing what or who Anna Wenne was, we would know whether this indicates the entrance to a shop or to a theater.

“Anna Wenne,” however, was as much an invention as everything else in the painting.

Paul Klee, Window Display for Lingerie, 1922. On close reading, this painting is full of sexual ambiguity.

A few years ago, Marta Schneider Brody, writing in The Psychoanalytic Review, astutely considered the significance of the name. She points out that Klee’s signature, although so small we almost cannot see it in reproductions of Window Display for Lingerie, is just to the right of the name Anna Wenne (not the usual place for a signature). The artist used only his last name. Brody suggests he invented “Anna Wenne Klee” for a reason, a surmise corroborated by another painting, from 1923, that has the name Anna Wenne on the opposite side from the name Paul Ernst—a reversal of Ernst Paul, Klee’s actual first two names—as if both of these people were the artists. “Anna Wenne,” Brody writes, “may be an imperfect anagram for the German … Mann Nennen Ann, a man named Ann. The anagram is formed by transposing the letters and inverting the letter W to form the letter M.”86

“Anna” was the name of Klee’s maternal grandmother. Anna Frick was the person who had started him, at about the age of three, making art, and who had protected him as a left-hander. It was under her guidance that he developed the idea of painting and drawing being forms of play. This occurred at the same time in his early childhood when he wanted to wear “ravishing lace-trimmed panties” and “was sorry I was not a girl myself.”87

ANNI ALBERS JOYFULLY RECALLED that every six months or so Klee would tack his most recent work to the walls of a corridor at the Weimar Bauhaus. These displays were among the greatest experiences of her life. She and other people spent hours deliriously studying the work; it’s easy to see why.

To someone like Anni—sexually ambivalent, determined to shake off the traditional expectations of what women were to do with their lives—the crossing over suggested by Window Display for Lingerie, the fanciful rather than grave approach to the issues at hand, was liberating. So was the further doubleness of “Eingang—Entrée.” The word for “entrance” is masculine in German (der Eingang) and feminine in French (une entrée). With entrance itself such a sexually suggestive idea, the use of both languages is a stroke of Klee’s genius. The combining of male and female roles not only pervaded Klee’s work at the Weimar Bauhaus; it was also apparent in his atypical life, where, in Lily’s absence, he was Felix’s main caregiver as well as the family cook.

KLEE’S ART BROUGHT the spirit of surrealism to the Bauhaus, though Klee abhorred the personal flamboyance of its well-known practitioners. His lack of “image” made the candor and psychological complexity of the work palatable to people like Gropius, Kandinsky, and the Alberses, all of whom deplored the self-conscious flaunting of personal quirks. The correctness of Klee’s demeanor made it much easier for them to accept the fact that his subject matter included cross-dressing and hermaphroditism.

Klee simply accepted the human imagination. In his diaries, he wrote that in his childhood he “imagined face and genitals to be the corresponding poles of the female sex. When girls wept I thought of pudenda weeping in unison.”88 His 1923 Lomolarm depicts a crying man whose eyes and nose have a distinct resemblance to “pudenda weeping.” He could not have been more matter-of-fact about the associative workings of his mind.

Klee did not conceal his own sexual uncertainty. In addition, there are times when hostility to women is plainly visible in his art. In his diary, he wrote, “Sexual helplessness bears monsters of perversion. Symposia of Amazons, and other horrible themes … Disgust: a lady, the upper part of her body lying on a table, spills a vessel filled with disgusting things.”89

At the Bauhaus, Klee often painted dominatrixes and androgynous characters who resemble evil conquerors. He usually made women grotesque. His 1923 Ventriloquist Caller in the Moor depicts a creature who is about 70 percent breast. These full, sagging mammaries have a lower contour that also appears to outline buttocks; the crack between them is explicit. Inside these organs that are both breasts and buttocks are many monstrous little characters—part human, part amoeba, one a cross between a donkey and a mermaid. The creature stands on tapered legs, and has tiny malformed arms and, on an abstracted human head, a mouth like that of a fish.

Yet the effect of the painting is by no means unpleasant. The fantastic orchestration of the background is a vibrating, irregular grid that gives the impression of exotic silk. It is a sheer marvel of watercolor painting, a superhuman use of that unforgiving medium. And the creature herself, for all the ways that she is horrific, seems to be singing with joy. Balanced precariously on a sort of unmoored dock, with a mermaidlike form suspended on a thin line from her right breast/buttock, she has magical power. Even if everything appears about to topple, it remains upright; what should be impossible is possible.

In 1956, Erwin Panofsky, the great scholar of northern Renaissance iconography, taking a rare look at modernism, wrote that Klee showed Pandora’s box as a vase with flowers in it “but emitting evil vapors from an opening clearly suggestive of the female genitals.”90 Gropius may have founded the Bauhaus as a design school, but it became a refuge that permitted unprecedented freedom of artistic expression, a safe environment where people like Klee could allow themselves to present, without fear of judgment, their most extreme fears and fantasies.

KLEE SAW HIMSELF as simultaneously a “pedantic” father, an “indulgent uncle,” an “aunt [who] babbles gossip,” a “maid [who] giggles lasciviously,” “a brutal hero,” “an alcoholic bon vivant,” “a learned professor,” and “a lyric muse, chronically love struck.”91 His art not only allowed for this multiplicity but also celebrated it. He wrote in his diary, “So much of the divine is heaped in me that I cannot die. My head burns to the point of bursting. One of the worlds hidden in it wants to be born. But now I must suffer to bring it forth.”92 The program of the Bauhaus was to mold universal designs, but it was also a haven for people unembarrassed by their passions.

Grohmann wrote, “Klee was not incapable of loving or responding to love, but as ‘nothing lasts in this world,’ love to him was an ever incomplete thing, a mere part of the eternal flux of things.”93 Klee can also be seen as having loved his grandmother so intensely that her death early in his life was so painful that he had to expand his horizon beyond actual life. He did so on paper and canvas, not in his existence outside the confines of his studio. He wrote, “Art plays an unknowing game with things. Just as a child at play imitates us, so we at play imitate the forces which created and are creating the world.” For artistic creation was as real as the making of life itself. Klee said he felt “as if I were pregnant with things needing forms, and dead sure of miscarriage.”94 Creating art was like giving birth, accompanied by the same overwhelming thrill and also the periodic bouts of fear.

When the people at the Weimar Bauhaus saw Klee’s Where the Eggs and the Good Roast Come From, they observed a rooster as the creature laying the egg. A male animal, thus, could give birth—and could also get cooked. When, the year the Bauhaus closed, Klee made a painting of a pregnant male poet, the underlying notion was the same: to nurture art was like nurturing a new human life, and could be done by men or women. In Adam and Little Eve, Adam, clearly a self-portrait, wears small drop earrings, and Eve, rather than being a seductress, looks like a small girl who is being abducted. Man as woman, sexual vixen as child, innocent as demon: Klee reveled in the reversals. The Bauhaus was a place to expand his originality, unfettered and encouraged.