Once everyone had accepted the idea that the Bauhaus in Weimar was no more and was preparing to leave, Klee decided to move to Frankfurt. But when representatives from the city of Dessau came to Weimar on February 12, 1925, they met with the Bauhaus faculty in Klee’s studio. It was there that Kandinsky and Muche were delegated to go to Dessau a week later to look around.

Lyonel Feininger felt that Klee had contemplated moving to Frankfurt instead of staying with the school because he thought only of his own interests, not of the future of the Bauhaus. While others respected Klee’s detachment, Feininger considered it unacceptable. Feininger wrote Julia that Klee was concerned “entirely” with his own “business and no one else’s.”184

Feininger’s resentment grew into rage. The only Bauhaus faculty member who was jumping ship was Gerhardt Marcks, who was moving to Halle. Everyone else, except for Klee, was valiantly struggling with the decision to move to Dessau, accepting the requisite personal sacrifices and inconvenience. While all of the painters were suffering from financial problems and would have preferred to work independently had that been possible, Feininger disparaged the way Klee kept his head in the clouds and was the last to wake up to the realities the rest of the group had already acknowledged. “Dear old Klee, he was quite upset yesterday, and said, ‘Yes, now I am beginning to understand you!’ He would have preferred to take ‘a good long pause.’ “185

That Klee only now grasped the urgency of the situation, and did so phlegmatically, was intolerable to the American. Most of the people at the Bauhaus admired that this was an intrinsic part of who Klee was, but Feininger was among the bitter few who were enraged by Klee’s apparent calm.

WHEN KANDINSKY AND MUCHE and their wives reported that the masters’ houses would be ready in October, their future inhabitants were ecstatic. The location where the Mulde and Elbe rivers met—at a confluence with fine prospects for fishing, sailing, and motorboating—was ideal. Yet while everyone else was enthusiastic, Klee was not. Feininger complained to Julia that Klee remained passive while still waiting to hear about his possible employment in Frankfurt. “Does nothing!” he barked.186

In fact, Klee was assessing the overall situation—with warranted skepticism. Gropius, having embraced the move initially, got cold feed about it in mid-March. Only a third of the necessary funding had been assured; the masters’ houses were not such a certain thing after all.

Felix Klee later recalled, “Klee remained rather reserved even towards his students. At the Bauhaus, we had nicknamed him ‘The Good God,’ which held a hint of nastiness, and you can easily imagine that he had to show some reserve. But it was a protection rampart needed by the modest and thoughtful man he was.”187 If Feininger did not find him an enthusiastic part of the team, it’s because he always needed to mull things over and contemplate the various aspects of a situation in his own way.

AS THE BAUHAUS PREPARED to leave Weimar for Dessau, there was considerable disagreement concerning the overall direction of the school. Moholy-Nagy saw the direction of art depending more and more on mechanical effects, and favored projected images, both slides and movies, over old-fashioned “static painting.” It was an approach that made Klee “very uneasy.” Klee’s own belief that nature, and what was organic and instinctive, was vital to art, and his attachment to ancient and so-called primitive forms of expression for their direct connection to human feeling and handwork had no place in the trend championed by Moholy-Nagy. Moreover, Gropius deemed Moholy-Nagy’s approach “the most important at the Bauhaus.”188 All of this added to Klee’s uncertainty as to whether he should remain with the school. What was going to happen, and would he be able to continue on his own terms, once they left the city of Goethe?

1. PAUL KLEE, Gifts for J, 1929. This painting commemorated the unusual arrival of Klee’s gifts for his fiftieth birthday.

2. PAUL KLEE, The Potter, 1921. While most of Klee’s subject matter had no precise location, this watercolor depicted one of the most active workshops at the Bauhaus.

3. PAUL KLEE, Postcard for the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition. In this small image, Klee evoked the fantastic energy and originality of the upcoming presentation of the Bauhaus’s achievement from its first four years.

4. PAUL KLEE, Battle Scene from the Comic-Fantastic Opera The Seafarer, 1923. In a single painting, Klee made violence seem comic, and presented what was initially charming as being fraught with danger.

5. PAUL KLEE, Individualized Measurement of Strata, 1930. This painting, completely opposite in nature from its formulaic title, reveals Klee’s extraordinary ability to make lively movement and establish rich rhythm with limited forms and colors.

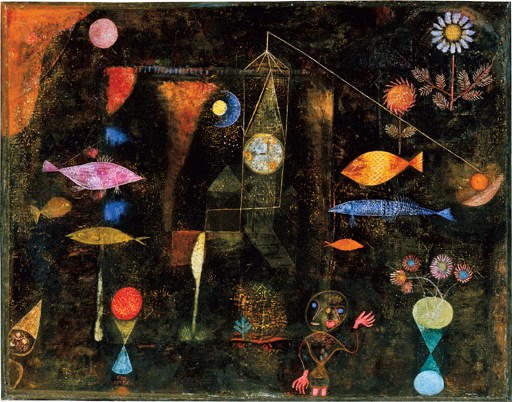

6. PAUL KLEE, Fish Magic (Large Fish Picture), 1925. With an aquarium full of tropical fish at home, Klee was riveted to the underwater universe.

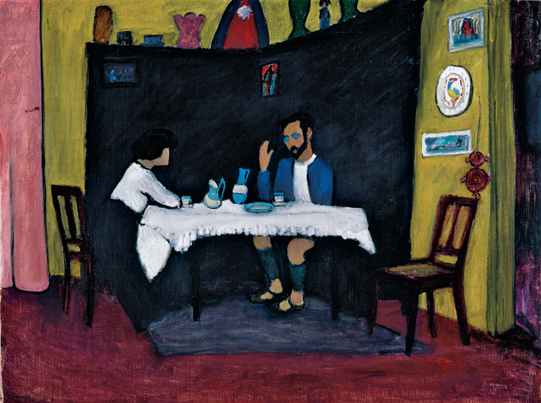

7. GABRIELE MÜNTER, Kandinsky and Erma Bossi at the Table in Murnau, 1912. In Münter’s country house in a Bavarian mountain village, Kandinsky pushed his art into unprecedented realms of abstraction.

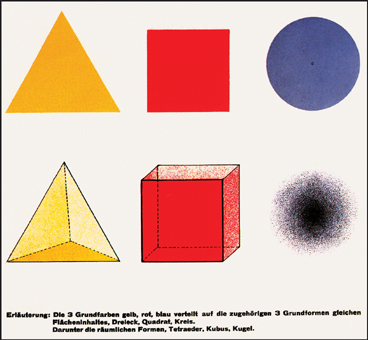

8. WASSILY KANDINSKY, Theory of Three Primary Colors Applied to the Three Elementary Forms. This image was printed in Staatliches Weimar in 1923.

9. WASSILY KANDINSKY, Small Worlds IV, 1922. Shortly after arriving at the Weimar Bauhaus, Kandinsky produced a series of prints in various media that remain to this day among his best-known work.

10. WASSILY KANDINSKY, study for the mural painting of the Juryfreie Kunstschau, 1922. During his first year at the Bauhaus, Kandinsky designed murals that the students executed and that realized his lively abstract compositions on a new scale.

11. WASSILY KANDINSKY, Too Green, 1928. Kandinsky made this painting to give to Paul Klee on Klee’s fiftieth birthday. The circle had great spiritual significance and suggested eternity.

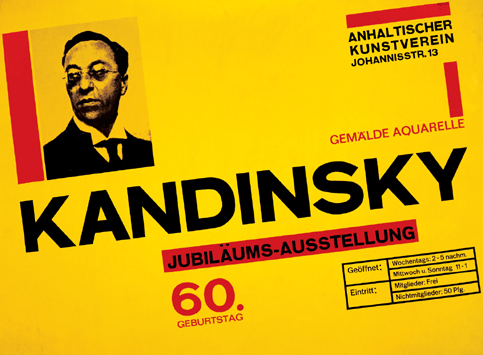

12. HERBERT BAYER, Poster for Kandinsky’s 60th Birthday Exhibition in Dessau, 1926. Bayer’s design announced one of Kandinsky’s most important exhibitions ever, a great event for everyone at the Dessau Bauhaus.

13. WASSILY KANDINSKY, Postcard for the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition. Like Klee, Kandinsky helped promote the Bauhaus Exhibition in a way that conveyed the remarkable adventurousness of the new school.

14. WASSILY KANDINSKY, Little Black Bars, 1928. Kandinsky’s paintings from the Dessau Bauhaus invite literal interpretations at the same time as they belong purely to the imagination.

15. PAUL KLEE, Dance of the Red Skirts, 1924. Having imagined demons ever since he was a small child, Klee inhabited and created a universe unlike anyone else’s.

WASSILY KANDINSKY, Composition VIII, 1923. Kandinsky used vibrant colors and bold, imaginative forms to evoke sound as well as emotion.

ON MARCH 31, 1925, Paul and Lily Klee gave a farewell concert in Weimar. It was the third occasion in recent months that they had played duets in public. For this event, they performed sonatas by Bach and Mozart together and Lily played, solo, two fugues and preludes from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier.

As long as they could, the Klees continued to relish the cultural pleasures of Weimar. They attended a recitation of The Grand Inquisitor, by Midia Pines, a well-known Dostoevsky reciter, and enjoyed two evenings of Kurt Schwitters reciting his own fairy tales. Schlemmer staged Don Juan and Faust by Grabbes, and there were concerts and theater performances. Béla Bartók performed Bluebeard’s Castle and his ballet The Wooden Prince. Even as the Bauhaus was being forced out, Germany’s new capital offered endless treats. Hindemith spent two hours in Klee’s studio one afternoon before performing that evening.

Klee’s work was given a major exhibition in Weimar that spring, as was Kandinsky’s. It was hard to believe that the period of glory was coming to an end.