In 1923, during his first full year at the Bauhaus, Kandinsky painted Composition VIII (see color plate 16). His new life in Weimar was having splendid results; he considered this large canvas the pinnacle of his own work after World War I.

Grohmann perceived Composition VIII as the exemplar of the “creative freedom” Thomas Mann identifies in Doctor Faustus. “Every note, without exception, has significance and function,” Grohmann points out, while there is, at the same time, a welcome and radical “indifference to harmony and melody.”70 In this painting, which is nearly six feet high, each of the many individual elements radiates power. Every circle, dot, squiggle, triangle, checkerboard, and dash functions independently and has inner strength. The spare, vibrant colors add to the punch. And while each form exerts its own force, the elements also work in an energetic, deliberately cacophonous relationship to one another; this, Grohmann asserts, “results in cosmic order, law, and aesthetic gratification.” He goes on to quote Mann’s Leverkuhn, declaring, “Reason and magic may meet and become one.”71

In his friend Grohmann Kandinsky had found the perfect apostle. Kandinsky’s own published writing about his Compositions lacks Grohmann’s gaiety. In On the Spiritual in Art, the painter calls his Compositions “the expressions of feelings that have been forming within me …(over a very long period of time), which, after the first preliminary sketches, I have slowly and almost pedantically examined and worked out.”72 Groh-mann managed to elicit livelier language from Kandinsky in a personal letter. In this document, which Grohmann cites, the painter lets his guard down and allows a warmth and fire to come through. In the book he wrote about the painter, which remains the best firsthand account of Kandinsky and his work, Grohmann brings us closer to Kandinsky’s mystical engagement than did Kandinsky in his self-presentation. Elucidating the breakthrough achieved by Composition VIII, Kandinsky wrote Grohmann that the circle

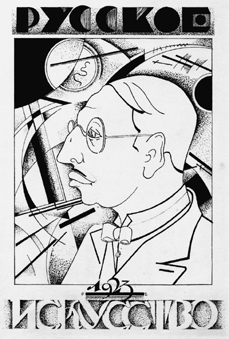

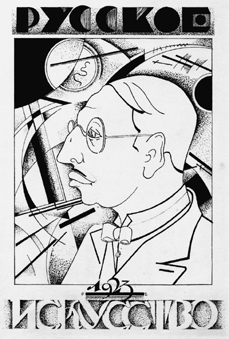

Serge Chekhonine, sketch for a magazine cover with a portrait of Igor Stravinsky, 1923. This image shows Stravinsky in the same year that he visited the Weimar Bauhaus for a performance of L’Histoire du Soldat The artist clearly saw the impact Kandinsky’s art had made on the composer.

is a link with the cosmic. … Why does the circle fascinate me? It is

(1) the most modest form, but asserts itself unconditionally,

(2) a precise but inexhaustible variable,

(3) simultaneously stable and unstable,

(4) simultaneously loud and soft,

(5) a single tension that carries countless tensions within it.73

Grohmann also quotes the responses Kandinsky gave to the psychologist P. Plaut, who sent out a questionnaire polling artists on some of their practices. Kandinsky informed Plaut, “I love the circle today as I formerly loved the horse, for instance—perhaps even more, since I find more inner potentialities in the circle, which is why it has taken the horse’s place. … In my pictures, I have said a great many ‘new’ things about the circle, but theoretically, although I have often tried, I cannot say very much.”74

The mix of hesitancy with passionate conviction, that abiding faith in himself paired with self-doubt, defined Kandinsky. So did his ability to feel greater animation and life in an abstract form than in his favorite animal. Color and shape were more real to him than living beings.

THE ELUSIVE RUSSIAN ARTIST maintained a persona of imperial detachment, but in his controlled, abstract art he used distilled forms to reveal his inner furies. He urged the Bauhaus students to take his same approach. In Kandinsky’s classes, the younger artists did exercises to express aggression with triangles and to suggest calm with squares. They employed the circle, the form that led to the fourth dimension, to invoke the cosmic.

That realm of the circle, the shape he made blue, was the one in which Kandinsky lived mentally. Married to a mundane woman who perpetually fretted about everyday occurrences, he escaped into his own mental territory. Nina suffered, for example, from a severe fear of fireflies; she was convinced they would burn her on contact. Kandinsky tried, unsuccessfully, to reassure her; where he found nature magical, she became terrified. His way of coping was by mentally inhabiting the world he evoked in his paintings.

When Kandinsky tried to capture this imagined territory verbally, as he did ad nauseam, in endless written treatises on his approach to color and form and on his theories about art as a form of investigation, the results don’t have the impact of his paintings. But the Compositions themselves present his invented universe in such a way that it is as welcoming as it is unknowable. And they soar with vigor and energy.

IT WAS DURING this period of his life at the Bauhaus, when Kandinsky was making Composition VIII and similarly euphoric works while existing completely outside the earthly sphere, that he had the meeting with Klee, already described, in which they went to a café and, after counting their marks, had to return home without coffee. Because they had completely lost whatever wealth they had in Russia, the Kandinskys were in even worse straits than the Klees, while they were used to a higher standard of living—or at least longed for one. The artist could scarcely afford crates to ship paintings to exhibitions, while his wife craved new dresses and hats.

In spite of a pressing need for cash, Kandinsky, like Klee, was content to be paid in canned food for the artworks sold by Galka Scheyer. On January 17, 1924, he wrote Scheyer from Weimar with his specifics: “Fruit in the larger cans because there probably aren’t any smaller—otherwise 1 lb. or 1/2 lb. would be much better. Vegetables we eat mainly as a side dish along with potatoes, so we can use smaller cans, but now and then larger ones would also do.”75 When he wanted to be diplomatic and agreeable, he evinced charm and generosity. Kandinsky tried to persuade Scheyer to take a larger commission; if, however, she insisted on forgoing it, she could just increase the amount of tinned food. He was determined that she not deplete her precious supply of cash at the moment when she was just starting his enterprise.

His own financial situation would improve in 1925 when the Kandinsky Society was formed. That organization consisted of a group of subscribers who gave money, with each receiving a watercolor at the end of the year. Once the society was active, their support provided the painter with a dependable few thousand marks annually.

Kandinsky’s arrangement at the Weimar Bauhaus was not unlike Klee’s. It enabled him to devote a considerable amount of time to his own painting, in exchange for which he did a limited amount of teaching and undertook some administrative duties. But for him the effort to combine writing, teaching, painting, and helping Gropius with administrative and diplomatic matters was often immensely frustrating. Kandinsky generally felt that he should be doing something other than the task at which he was currently working. Although Grohmann observed that “from the outset Kandinsky felt at ease in Weimar, for he was surrounded by men who understood him,”76 he suffered, at the Bauhaus as everywhere else, from being one of those people who rarely believes he is achieving his objectives. Kandinsky always lamented what he was not doing, and was dissatisfied with what he was doing.

He tended to analyze his own analysis. The Russian had none of the devil-may-care decisiveness of Gropius or the sheer delight in nature and all forms of creativity enjoyed by Klee; rather, he was mostly dissatisfied. There was, indeed, always an “and,” but, as in his love life, there was never a perfect moment of unequivocal joy—except at the moment of making art.

In 1924, the Braunschweigische Landeszeitung published an article calling Nina and Wassily “Communists and dangerous agitators.” In response, on September 1, Kandinsky wrote to Will Grohmann from a holiday in Wennigstedt, a resort on the North Sea, “I have never been active in politics. I never read newspapers. … It’s all lies. … Even in artistic politics I have never been partisan … this aspect of me should really be known.”77 He was so disgusted by the accusations linking him with the political party now ruling Russia and with forces that might undermine the stability of the world he was now enjoying that he considered leaving Weimar to become a less public figure. But, as he wrote Grohmann a month later, he really believed in the purposes of the Bauhaus.

Beyond that, in spite of his perpetual personal woes, he had a goal that was entirely his own, far loftier than Gropius’s aims of good design for industrial mass production and the joining of the various arts. “In addition to synthetic collaboration, I expect from each art a further powerful, entirely new inner development, a deep penetration, liberated from all external purposes, into the human spirit, which only begins to touch the world spirit.”78 Kandinsky always pushed everything to its extreme—into that disembodied realm where he might find a well-being absent in his everyday life.

IN LATE 1925, Oskar Schlemmer heard Wassily Kandinsky give a Bauhaus Lecture—a special event whose audience consisted of many of the school’s leading figures as well as important outsiders. Schlemmer disliked most of what he heard. Kandinsky seemed to denigrate everything except for nonobjective painting, and Schlemmer was offended not just by what he said but by the stridency with which he said it. Yet the speaker was fluent and intelligent: “He also spoke with resignation of his own isolation, of the fate of the modern artist.”79

For long periods, Kandinsky had tried to verbalize his ideas in a room he had in Weimar exclusively for writing. “The combination of theoretical speculation and practical work is often a necessity for me,” he wrote Grohmann. Yet as he approached the age of sixty, with his usual feeling that he was doing one thing while he should be doing another, he was impatient with the amount of time he had spent formulating and verbalizing his ideas on paper rather than engaging in painting. In the fall of 1925, he informed Grohmann, “For three months now I haven’t painted as I should, and all sorts of ideas are begging to be expressed—if I may say so, I suffer from a kind of constipation, a spiritual kind.”80 The man who could describe himself as pedantic and spiritually constipated was, however ferocious the diatribes against him from others, his own worst critic.