By that fall, a year after the Bauhaus had opened, Albers was there. He later wrote, “I was thirty-two, … threw all my old things out the window, started once more from the bottom. That was the best step I made in my life.”31 Gropius’s workshops in Weimar were a chance to put Bottrop, figurative art, and—he initially thought—the need to teach behind him. He replaced a life of isolation and borderline poverty with sympathetic companionship and, at least, rudimentary room and board.

He took the foundation course required of all students. But he was older than most of the others, and already had his own ideas. In little time, Albers had invented a new art form. Unable to afford paints or canvas, he searched for free materials with which to make art. The Weimar city dump was not far from the Bauhaus; pickax in hand and rucksack on his back, he began to hack up discarded bottles and other bits of broken glass, and filled his pack with the fragments that interested him the most.

Back at the Bauhaus, he used lead and wire to assemble the shards into vibrant compositions. Albers extracted a radical and startling beauty from the detritus. The art he made was organized yet playful. With his unerring eye and instinct for visual rhythm, he constructed assemblages that were harmonious and at the same time possessed of the unguarded exuberance of his happiest frolicking.

In that period of financial hardship and abrupt social change, many German artists were focusing on society’s woes, making human suffering their primary subject matter. Albers organized the resurrected junkyard pickings into windows that sang. He mounted three of them on light boxes and hung others so they would be penetrated by daylight; the light pouring through them intensified that spirit of sheer pleasure.

Albers’s initial exploration at the Bauhaus also included a print portfolio cover composed of oscillating horizontal rectangles, and some imaginative efforts to create wooden furniture. In the next thirteen years—he stayed at the school longer than anyone else—he would design and make tables and chairs, formulate new alphabets, plan buildings, use a camera in unprecedented ways, and progress from assembling broken bits of glass to stenciling and sandblasting flat panes of the material in compositions of mathematical rigor and great artistic power. Without the originality of Klee or the intellectual reach of Kandinsky, he would be the school’s greatest polymath, proving his versatility in many domains. He would also become a gifted writer and public speaker who helped articulate for the larger public much that was vital to the Bauhaus approach, and the teacher whom Gropius credited above all others for furthering the school’s educational mission.

WHEN EIGHTEEN-YEAR-OLD Marcel Breuer arrived at the Bauhaus in 1920, the first person he asked for was Johannes Itten. “I had to wait for a while and then he came out in the corridor. And I didn’t tell him anything, it was obvious what I wanted.”32 Breuer, as Itten knew, had come as a new student and was trying to figure out what his first moves should be, given that the Bauhaus did not yet have much structure. Breuer presented the teacher of the foundation course with a small book of drawings he had made.

He went through them this way: “Hmmm, hmmm …hmmm.”

He was a very arrogant man, you know, in the first moment I had an antipathy toward him. You know, it’s a kind of importance tactic. … He believed in himself … very much …Mrs. Mahler, who was Gropius’s wife at that time, she knew Itten and she thought this is an interesting man and he made an impression of an interesting man. And the shaved head …He was originally Swiss, Itten, and had been a painter, and had in Vienna a private art school, and then Gropius invited him to come with him to the Bauhaus.

Describing his very first day in Weimar forty years after the fact, Breuer recalled how, feeling like an outsider as a Hungarian Jew, his loneliness and uncertainty were exacerbated by Itten’s treatment of him. But Breuer did not lose hope. He decided to go into the glass workshop. There he encountered a tall man in a military cape and pointed black hat who picked up a large brush and splattered paint all over a piece of metal. This was Papp, another Hungarian.

Breuer saw a piece of paper on the door. His was one of the three names written on it. But because he knew little German, he did not understand why.

So I asked the guy who was next to me, what does that mean? I somehow stuttered it out. He understood what I meant. He said something like … “You are the man who on that week has to keep order in the classroom.”

I said, “I don’t understand.” And he had seen that I didn’t understand much, so he said, “Take a brush and a broom and sweep the floor.” “What is a broom?”

The stranger reached for a broom and handed it to Breuer. It was Albers, who had arrived at the school only shortly before Breuer. Simply by dint of being approachable and down-to-earth, the carpenter’s son from Bottrop had already assumed a unique position at the Bauhaus.

IN JANUARY 1921, Albers wrote Franz Perdekamp from Weimar, “So often or so many times I have wanted to write to you about so many things, but the way things go here, either all the liveliness here stops me writing about our young people or an upset stomach about over-rich Christmas parcels. Or cold compresses about grotesque love affairs. In short there is too little boredom, so that I had to work out that my first new year’s resolution would have to be to give up letter writing. The following idea also popped into my head: ban all women.” He told Perdekamp that he was in an “expensive but great apartment” but needed money. He had been forced to borrow money from friends “because the canteen cash in my purse had dwindled so much. So: things go wildly up and down. So much so that I need to apply the brakes. … About my old surroundings, the new people and the Bauhaus.

Probably a lot needs to be broken. And possibly it will be worse because it should have been broken long ago.”33

The detritus he was hacking up in the Weimar dump could be seen as a metaphor for the preconceptions—his own and his father’s—that he was shattering. The octogenarian Josef Albers I knew disapproved vehemently of the notion of art as autobiography; nonetheless, his work often reflected his own needs and his psychological state. The glass assemblages were analogous to what the Bauhaus facilitated: destruction and resurrection. Coaxing beauty from what to others was nothing but refuse, he demonstrated the possibility of transformation that was one of the Bauhaus’s greatest offerings. (See color plate 19.)

ALBERS’S TEACHER for the Bauhaus preliminary course was Gertrud Grunow, a musician who taught under Itten’s supervision. Albers wrote Perdekamp about the liberating effect of her educational method: “You cannot give it a name. It is about loosening up of people. …You have to walk in tones or experience them while standing, move in colors and light and form.”34 A single course sufficed, however. It was not in Albers’s nature to study under someone else. On February 7, 1921, he was one of three students who applied to be exempted from the preliminary drawing course. He was granted his wish on the basis of his work with Grunow, which was considered exceptional.

Eager as he now was to enter a workshop, Albers was not sure he could afford to remain in Weimar. He was still a student, even if he didn’t act like one, and had no money coming in beyond his regular stipend from the regional teaching system back in Bottrop, which was diminished by what he had to pay them back for his absence.

He wrote the officials in Westphalia asking for more support for his training at the Bauhaus. He claimed it would make him a better instructor when he returned to teaching in Bottrop—although he had no intention of honoring his agreement to go back. The Bauhaus masters, meanwhile, told the habitué of the junkyard that his glasswork was not an acceptable artistic medium and that he had to study wall painting. He refused, jeopardizing his future even more.

At the end of the second semester, Gropius “reminded me several times, as was his duty, that I could not stay at the Bauhaus if I persisted in ignoring the advice of my teachers to engage first of all in the wall-painting class.”35 Treating the directors threat as just another challenge, Albers continued to work only with bottle shards on flattened tin cans and wire screens. Then, at the end of his second semester, he was required to exhibit his work to date.

“I felt that the show would be my swan song at the Bauhaus,” he later recalled. In fact, it was the reverse. Following the presentation of his assemblages of painted bottle bottoms and other glass fragments he had hacked up, he received a letter from the Masters’ Council not only informing him that he could continue his studies but asking him to set up a larger facility for working in glass at the school. “Thus suddenly I got my own glass workshop and it was not long before I got orders for glass windows.”36

BETWEEN 1922 AND 1924, Albers made a window for the reception room of the director’s office at the Weimar Bauhaus (see color plate 21). A mosaic of syncopating rectangles, it glowed a vibrant red, with other colors quickening the pulse. To everyone who entered that room, the mélange of forms instantly conveyed the energy and optimism of the new institution. This was not the only Albers work that greeted visitors waiting to see Gropius. He also made a large table and a shelf for magazines and catalogues, both composed of lively arrangements of contrasting light and dark woods. There was a complex storage unit, constructed from white milk glass and stainless steel, that turned a corner. Albers’s unusual glass lighting fixture depended on a recently developed clear bulb, while his row of folding seats looked like something out of an ancient monastery. All of these objects used right angles and bold planes to create a lively rhythm. At the same time they subtly provided a sense of orderliness, for their measurements were all based on the use of a single underlying unit. In the corner cabinet, the shelves were precisely two centimeters thick; the recesses in the glass doors were two centimeters wide; and every other dimension was a multiple or precise fraction of two centimeters. The result is a soothing feeling of stable underpinnings: an important message to impart, given the crosscurrents of difficulty at the Bauhaus.

The glass workshop at the Weimar Bauhaus, ca. 1923. Having been told by the Bauhaus Masters’ Council that if he worked only in glass he would not be allowed to remain at the school, Albers showed such originality and mastery of the medium that they ended up asking him to run the glass workshop and to be one of the first students to serve as a master.

These pieces were in the vernacular of the other Bauhaus craftsmen, but Albers brought to his designs his own eye for simplicity, purpose, and scale.

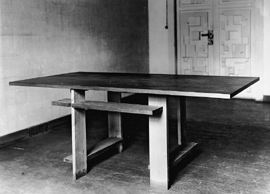

Lucia Moholy-Nagy, photograph showing a table designed by Josef Albers for the reception room to Walter Gropius’s office, ca. 1923. Albers’s furniture depended upon minimal elements that were measured as precisely as the notes of a work of classical music.

His furniture was not startlingly original, but it was refined in a particular way. And in adding the dash of art to these functional objects, Albers had made a major leap forward.

Albers’s designs are distinctive in both their relative airiness and their sureness of form. The voids have a sculptural richness. Planes interlock in crisp rhythm. The way in which elemental shapes embrace and respond to one another clearly betrays the painter’s eye. The corner cupboard was wonderfully inventive in details like its concealed liquor storage, but its juxtapositions of forms and materials were equally surprising. What Albers made was practical, but it also betrayed a rare inventiveness and artistic eye, and a courageous yet seemingly effortless originality, that were among the most vital goals of the Bauhaus.

IN GRID MOUNTED, a glasswork of that period, Albers applied a principle he had discerned in Giotto’s work. He built the whole out of minimal vocabulary of form, confining himself to a single unit of construction. What necessity imposed on the Italian, Albers imposed on himself. It was the same principle by which Klee limited himself to only a few colors, or to variations of a single form. In Grid Mounted, Albers deliberately used, as his sole means, glassmakers’ samples that he filed down to small, uniform squares. He then organized these like components in a checkerboard pattern and bound them together with fine copper wire within a heavy iron grille.

Itten had used the checkerboard pattern as a teaching tool in his preliminary course, but Albers applied his own alchemy to the motif. Candid as it is in material and technique, the underlying units a tradesman’s means of showing types of glass for sale, in a range of hues and textures, Grid Mounted has a celestial radiance. The color juxtapositions create vigorous movement, and the lively interplay has a spiritual force, a sense of something miraculous occurring, as in Giotto’s Annunciation scenes. Having thrown himself into the making of this work with the enthusiasm of one who has found his way, Albers breathed life into the grid.

This was Josef Albers’s particular contribution to the Bauhaus: manifest in his glasswork, his functional objects, and his teaching. He deliberately built an orderly, well-regulated universe in which one both subscribed to rules and exercised one’s imagination. The tied-down squares of color in Grid Mounted are full of surprises, free-spirited within their very rigid boundaries. Again, an abstract artwork was uncannily like its maker. It appears grounded in the practical—the craftsman’s manipulation of color and texture—but it is jubilant. On the surface, Albers adhered to accepted standards of comportment—he had nothing to do with the Mazdaist eccentricities of the Ittenites—but in his work he dared the outrageous. Grid Mounted is euphoria within the confines of structure.

LIKE KANDINSKY THAT SAME YEAR, Albers was hoping he would have the funds for a new pair of shoes. On March 22, he wrote Perdekamp:

Dear Franz! I have not thought about the shoe purchase for a long time. I expected to get money from home, but nothing doing. And so I do not have the ready money. And then it seems to me they would be more like mountain boots. But I want to be able to wear them as “good shoes.” So I can’t make up my mind.37

He was also uncertain about what his position at the Bauhaus would be, and whether he would find his niche there. He had made strides in his own work, but it wasn’t clear which workshop he should be in, and what he should be doing. At Itten’s beckoning, he was teaching the Bauhaus foundation course, but he considered his role as an educator only a temporary gig; he preferred making things, even if he lacked the support to do so exclusively.

During that period of unanswered questions, Albers encountered the intensely determined, strong-willed Annelise Fleischmann. The twenty-two-year-old daughter of a prosperous Berlin furniture manufacturer and of a woman whose family owned the largest publishing company in the world, Fleischmann had opted to leave behind her parents’ luxurious way of life, and their notion that she should settle down to a life of domestic ease like her mother’s. When she and Josef first met, she had not yet been accepted at the Bauhaus.

Josef was blond and outgoing; Annelise was dark-haired and brooding. She was smarting because Oskar Kokoschka had turned her down when she went to Dresden, her portfolio under her arm, to study art with him. “Why don’t you go home and become a housewife?” Alma Mahler Gropius’s lover had asked. Determined nonetheless to devote her life to art, she then enrolled in the School for Applied Arts in Hamburg, but left after deciding it was nothing more than “needlepoint for ladies.”38 Having persuaded her parents to let her go to the Bauhaus, she was turned down in her first attempt for admission. By then, she and Josef had met, and she was in no hurry to return to Berlin.

Josef offered to guide Annelise with some of the basic exercises in folding paper so that she might have a better chance on her second go-around. This time she was admitted. The heiress still was not certain, however, of where she stood with the man whom she described as “a lean, half-starved West-phalian with irresistible blond bangs.”39

There was a Bauhaus Christmas party at the end of 1922. Annelise attended dutifully, sat in the back of the room, and girded herself to get through an event where no one would notice her presence. Not only was she a newcomer; she was, in her own view, a perpetual outsider. She was certain that Father Christmas—Walter Gropius dressed as Santa Claus—would have nothing for her as he called out the names on the cards attached to his pile of gifts. Annelise was so surprised to hear her own name that she thought it was a mistake. But people were staring in her direction, waiting for her to get up, and she realized she should step forward to receive her gift. It was a print, rolled up, with a gold ribbon around it, of Giotto’s Flight into Egypt. Attached to that image from Giotto’s fresco cycle in Padua was a card with Josef Albers’s name on it.

The scene of the Virgin Mary on a donkey, the infant Jesus in her arms, with the triangulated mountain behind them perfectly echoing the form of the figures on the animal, embodied the harmony and beauty for which Annelise was longing. Josef knew the effect his gift would have. Besides, Friedel Karsch had, in August 1922, married Franz Perdekamp—to whom Albers had introduced her in Munich.

Josef had no shortage of women in his life—the ones who periodically made him swear off other members of the opposite sex—but Annelise Fleischmann was different. She had his consuming dedication to art, and a rare strength and intelligence. She had striking looks; while she wasn’t pretty, she had an utterly fascinating face. She was pensive and observant; little escaped her. She also offered access to another stratum of German society, although her background made her intensely uncomfortable. Josef’s attraction to a Jewish woman who wanted to devote her life to art and was eager to abandon the expected female role further distinguished him from almost everybody with whom he had grown up. Yet again he was making an extraordinary choice.

WHEN JOHANNES ITTEN LEFT the Bauhaus at the start of 1923, Albers was relieved. He thought that the teaching he had been doing at Itten’s request would come to an end, enabling him to concentrate his energies on his own work. But after Itten’s departure, Gropius came into the glass workshop at a moment when it was full of students and, in front of all of them, said to Albers, “‘You are going to teach the basic course.’” Albers later recalled the dialogue precisely: “I said, ‘What? I’m glad to have teaching behind me; I don’t want to do it any more.’ …He put me in his arms and said, ‘Do me the favor, you are the man to do it.’ He persuaded me. He wanted me to teach handicraft, because coming from a handicraft background on my mother’s side and also on my father’s side, I was always very interested in producing practical things. Gropius said ‘You take the newcomers and introduce them to handicraft.’ “40 He felt he had no choice.

Albers had found Itten’s preliminary course “at first quite stimulating,” but he came to dislike the teacher’s “emphasis on personality.” It bothered Albers that Itten’s presence was “terribly dominant.”41 Albers abhorred anything he considered disorderly or self-indulgent. He felt that character quirks should be concealed; a clear sense of purpose, and the appearance of harmony and balance, were essential in personal comportment and in art. He could hardly be expected to like the blatant eccentric who taught in a burgundy red clown’s costume and practiced Mazdaist rites.

Itten’s worst flaw in Albers’s eyes was that he was a bad painter. His work had a relentlessly deliberate spirituality, but to look at it was not a spiritual experience. The opportunity to make up for Itten’s weaknesses was irresistible. The mission Gropius gave Albers was “to counter the remnants of slack student attendance and mystical preoccupations in the wake of Itten’s departure” and to overcome “the reigning desultory attitudes.”42 In the fall of 1923, Albers began teaching eighteen hours a week—more than anyone else at the Bauhaus, even if he had to be off campus—mostly in the mornings. To his surprise, what he undertook reluctantly quickly became a consuming passion.

When toward the end of his first term he changed the course name from “Principles of Craft” to “Principles of Design,” it was because he was teaching a general approach to form that utterly captivated him. Emphasizing the need for visual clarity while simultaneously exalting the possibilities for visual trickery, Albers had found himself.

OFFICIALLY, HOWEVER, he was in limbo. Following Itten’s departure, László Moholy-Nagy had been appointed head of the preliminary course. For Albers to assume a position on the faculty, a second vacancy was required, but no one else was leaving. He was relegated to give his workshop in the Reithaus, a fifteen-minute walk from the main Bauhaus buildings.

The Reithaus, on the banks of the tree-lined River Ilm, had been built by the Grand Duke of Weimar. A former riding academy, it was not where students expected to go to learn about art. But if Albers felt like a second-class citizen for having been put there, at least his classroom had large windows that let in ample daylight. The windows also served to let in the students; the low-level bureaucrats who worked in the government offices above complained about the way the young people in Albers’s class would noisily climb in and out.

It irritated Albers that Moholy-Nagy, who arrived at the Bauhaus after him, had been made head of the course because of his seniority and past experience. Half a century later, Moholy’s name always elicited scorn and prompted Albers to remind people that the Bauhaus should not be glorified. The conflicts, power struggles, and hurt feelings there were the same as at any other institution, Josef and Anni both insisted; no place or organization, including the Bauhaus or Black Mountain College, where they were for sixteen years after the Bauhaus closed, was as interesting as art itself.