On April 22,1928, from the Dessau Bauhaus, Albers gave the Perdekamps an insider’s view of the uncertainties there:

Dear Franz. Dear Friedel

Today I want to write from under a blue sky. Because we got into the rain while cycling today and had to sit outside a long time.

The holidays are over and the return here from Berlin was not easy for me. Dessau is too small.

You have probably heard that all sorts of changes have been made here. Gropius left, because he wants some peace after all the quarrels and perhaps also because he sees more opportunities in Berlin. For now he is on an exchange visit to America. His successor is Hannes Meyer, who has already been here a year. He is an architect and will deal with the administration. The whole trend is such that there is not much scope for reform. Breuer, Bayer and Moholy have also left. I am staying. Though I hesitated for a long time. According to plan I will get a house in the masters’ settlement, when Moholy has moved to his new flat. We are looking forward to that.66

With Breuer leaving, Albers was to manage the furniture workshop. He was also exhibiting his glasswork and preparing an exhibition for the international art teaching congress in Prague, which would be held with the support of the Czech president, Tomás Masaryk, a great proponent of the Bauhaus.

Having just turned forty, he was dealing with age: “I am turning a bit gray and wear glasses when I read.” That emphasis on the ordinary and everyday comes through in his photography. When I went through the storage room for which Anni had given me the key after Josef’s death, I found piles of photographs and photo collages, as well as contact sheets and tins of film. As with the early drawings, Albers had essentially concealed this early figurative art—as if his obsession with the representation of the human body and various landscapes and buildings would later detract from the emphasis on pure line and undiluted color. While a handful of Albers’s photographs were known during his lifetime, the size and richness of the collection that he had squirreled away in a basement was extraordinary.

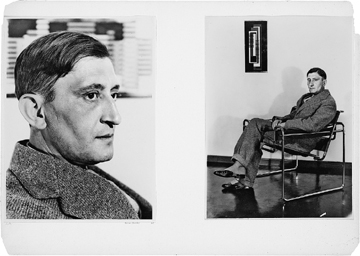

Umbo, Josef Albers 28, 1928. Albers took these two portraits by the photographer Umbo and pasted them side by side, making clear the possibilities of the different approaches one could take to a single subject.

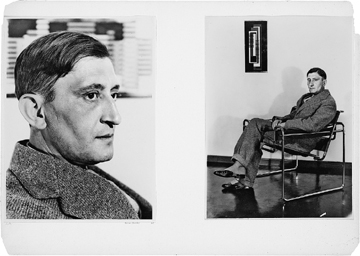

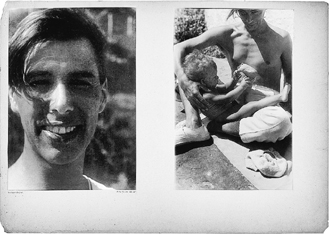

In addition to their exploration of the chromatic possibilities of black, white, and gray, the photographs further reveal Albers’s preoccupation with taking different approaches to the same theme. In the collages he carefully positioned, and pasted on cardboard, large prints alongside dozens of postage-stamp-size contact prints, so that the work vividly presents multiple responses to a single subject, and invites consideration of quality judgment, selection, and scale. He made these collages of his close-up photo portraits of the pensive Paul Klee, with Klee’s astonishing eyes, one pair after another, looking off into space as if to connect the artist directly with distant planets. He also made a collage from multiple images of Gropius frolicking on the beach at Ascona in 1930 with a woman named Shifra Carnesi. In each image, the former Bauhaus director—bare-chested as if just in from a swim, except that his hair is perfectly parted and combed—has a different way of embracing Shifra, who looks as if she is desperate to get into bed with him as quickly as possible. There is a sensuous collage of Anni relaxing in one of Josef’s jackets. Another, of her handsome brother Hans, is composed of large and small snapshots that present him as a rakish playboy with the world at his beck and call—as it was for this carefree young man in Berlin until the Nazis brought his life of sailing and opera-going and cavorting to an end he could not have imagined when these photos were taken. A decade after these images were shot of the dapper Hans leading the high life, he would leave Germany as a refugee, grateful to be saved by his rebellious sister and the brother-in-law he had admired from the start, however difficult his new circumstances were.

Josef Albers, Oskar Schlemmer IV, ‘29; im Meisterrat ‘28; [Hans] Wittner, [Ernst] Kallai, Marianne Brandt, Vorkursausstellung ‘27/’28; Oskar & Tut Sommer ‘28, 1927–29. Albers made this collage of his photos of Oskar Schlemmer and other Bauhauslers, taken over a two-year period. It captures the animation and style with which these inventive geniuses lived.

Josef Albers’s collage of photos of Gropius with Shifra Carnesi, taken in Ascona, 1930. Even in troubled times, life for the Bauhauslers contained more pleasure than most people realized.

Josef Albers, Herbert Bayer, Porto Ronco VIII, 1930. Bayer was an inventive graphic designer and a man who proved irresistible to many women at the Bauhaus, among them Ise Gropius.

Much of Albers’s photographic work concentrated on ordinary sights. Exalting the rhythm of parallel lines, he put close-up images of railroad tracks side by side. With his characteristic visual gamesmanship, he juxtaposed a photo of the view from the window of his new house, the bare trees black against the whiteness of the snow covering the ground, with one in which trees coated in fresh damp snow are white against the darkness of the earth on which the snow has melted.

His excitement as a child when he saw the black tiles as one world and the white squares as another never failed him. In these paired photos, the whites are a source of space and lightness and energy. These airy voids provide the oxygen essential for us to see all the depth within the blacks. These photo compositions all have the energy the little boy felt. At the same time, they are sophisticated, rational artworks in which the artist used juxtapositions of tone, line, and scale to create unexpected relationships.

As a photographer, Albers took the same approach evident in his early drawings, glass constructions, and furniture. His goal was to have the artist function only as a presenter of phenomena and server of possibilities he deemed far greater than himself. In his camera work, the subject emerges in fullest force. The marvelous construction of the Eiffel Tower, Kandinsky’s intelligent face made mysterious by clouds of cigarette smoke, the funny imperiousness and mystery of mannequins in a shop window: each is its essential self. With mechanical means, Albers animated these images that celebrate both what exists in reality and what exists only in the imagination.