In 1932, after the city legislature of Dessau voted to dissolve the Bauhaus and the school moved to Berlin, the city of Dessau was still obliged to pay faculty salaries—once the courts had determined that the contract with the masters had been terminated prematurely. So, for a while, Albers and Kandinsky and the others were able to manage, even if the school was now located in a derelict telephone factory rather than in the splendid headquarters Gropius had built for it only six years earlier.

Albers fared better than the others, since Anni’s family got them a nice apartment in the Charlottenburg section of Berlin. Besides paying the rent, the Fleischmanns covered the cost of refurbishing. While the few of his colleagues who had remained were living in reduced circumstances compared to what they had had in Dessau, because he had married a rich woman, Josef was helping her select new flooring (white linoleum, a revolutionary choice in 1932) and other details of their appealing, if smaller, nest.

They spent about a year there. On June 15, 1933, the Oberstadtinspektor of the Dessau City Council wrote Josef Albers a letter:

Since you were a teacher at the Bauhaus in Dessau, you have to be regarded as an outspoken exponent of the Bauhaus approach. Your espousing of the causes and your active support of the Bauhaus, which was a germ-cell of bolshevism, has been defined as “political activity” according to part 4 of the law concerning the reorganization of the civil service of April 7, 1933, even though you were not involved in partisan political activity. Cultural disintegration is the particular political objective of bolshevism and is its most dangerous task. Consequently, as a former teacher of the Bauhaus you did not and do not offer any guarantees that you will at all times and without reserve stand up for the National States.74

A similar document was sent to the other masters.

Not only would there be no pay in the future, but there was now a hitch concerning the overdue salary to which Albers was entitled. The nasty missive went on to explain, in a series of circumlocutions that even a person used to German bureaucratic gibberish would find difficult to understand, that what he had received for remuneration through the second week of April—his most recent salary payment—would be his last. This was justifiable, according to Oberstadtinspektor Irmscher Sander, “especially since recoverable salary payments with consideration of the fact that the private contract of employment was concluded according to #1, chapter 1, section 4 of the economy regulations of Anhalt of September 24, 1931 (statute book of Anhalt p. 63, of September 30, 1932) had been dissolved and that after the dissolution obligation for further payment of salaries no longer existed.”75

FRANZ PERDEKAMP, who had read Hitler’s Mein Kampf that spring, advised Albers to leave Germany if he possibly could. On June 10,1933, on a letterhead that read “Professor Josef Albers, Berlin.-Chbg. 9 Sensburger Allee 28” (with no mention of the Bauhaus), Albers wrote Perdekamp:

Dear Franz,

This is how it stands with us: shortly before Easter the B.H. was surrounded by police, the building and people were searched, many taken away and released after producing their papers. The house was closed, according to the press: because much incriminating evidence and illegal pamplets had been found. …

Three weeks ago, after much effort in many places, it was accepted that there was no incriminating evidence. They promised to remove the police seals, but did not do so. In mid-May we should have got our May compensation payments from Dessau. After a complaint at the end of May we received a notice: stopped by reason of the Law for the Renewal of the Civil Service. A few days ago the return of furnishings lent by Dessau to the Bauhaus and its workshops was required by 1st July. So the BH. is closed, no money and no furnishings. The staff has been cut. One had to show a family tree, one was politically suspect, one stays in Dessau—he had been part-time, now he is in full employment there.

So we are correspondingly happy.

Additionally the internal atmosphere—among colleagues—is no longer all right. Waiting for the end. What we worked for was in vain, now no money. No prospects. We make little plans.

During these weeks off I have retired to my little room and “ora et labora” alone.

As never before. And as making glass pictures has become too expensive since the summer, I have been making woodcuts, which I think are very good, one or two really clever. The other blocks are waiting. But a few days ago I found someone who will print them for me for nothing. I still have to get hold of paper and have some debts. I can’t pay the rent. But we still have some food from my parents-in-law, who are also not very well off.

My exhibition has been canceled.

I am prepared for anything.

Spiritual development continues in spite of everything, each individual has to decide how to hold out.

Art has always been a special occupation with special values.

“Art from the people” or “for the people,” as it is now said, are misconstructions.

Bach will never be played on the streets. It will always be “Baby, you are the star of my eyes” or something similar. Even if they dictated Wagner every day.

But thank goodness there’s still Whitsun and that will stay. But then the masses go on outings.

We send our best wishes from our work and beautiful nature.

Your Jupp76

In November 1933, Josef and Anni Albers left Germany forever.

ON MARCH 19, 1976, Josef’s eighty-eighth birthday, Anni had just finished making whipped cream to put onto a store-bought cake for a modest celebration with the actor Maximilian Schell and Schell’s tall and glamorous girlfriend, Dagmar Hirtz, when Josef complained of chest pains. Anni phoned the doctor, who advised her to drive him to Yale—New Haven Hospital.

Once he was in the hospital, however, Josef felt quite well. Schell had recently become a collector of paintings from the Homage to the Square series and had proposed enlarging two black and gray ones as a stage set for a performance of Hamlet, which he intended to direct and star in. When he and Hirtz visited the patient, they found him robust and cheerful. But the doctors advised that Josef remain in the cardiology unit under observation. The story put forward that day, which Anni had no reason to question, was that this was the first time he had ever been hospitalized.

On March 25, just as Anni was about to leave the house to pick up Josef and bring him home, she received a phone call: he had suddenly died—as cleanly and rapidly as he would have liked, with no pain or dread.

Within a couple of hours, once her brother was on his way to help with the practicalities, Anni telephoned me at my father’s company, where I was then working. “Anni Albers,” she announced, as she always did at the start of every phone call, in her soft but strong voice. Then came two more words: “Josef died.”

I commiserated, and she went on to ask me to go to Tyler Graphics, about an hour from where she and Josef lived, with a proof that Josef had approved in the hospital and would have wanted them to have so that his latest print series could still go into production. We made the necessary plans. When I hung up the phone, I realized, as I never had before, that everyone dies. Josef, by being as physically robust as a boy until the end (he still took brisk daily walks, rain or shine, at age eighty-seven), by creating art that belonged to all times, and by never showing any sign of waning energies, had enabled me to hold on to the hope that, even if ordinary people had to die, immortality might be possible. Now I knew that this could never be the case.

Anni and Josef Albers in the garden of their home at 8 North Forest Circle, New Haven, Connecticut, ca. 1967. The Alberses were like a two-person religious sect. They considered visual experience an unequaled source of stability and joy.

Only nine of us were present for the funeral rites, held three days after Josef’s death. In addition to Anni and me, they were her sister and brother and sister-in-law, the architect King-lui Wu and his wife, Vivian, Josef’s lawyer Lee Eastman, and Lee’s wife, Monique. While the other eight stood at the graveside for the Catholic service, conducted by the priest from the Holy Infant Church, I ceded to Anni’s request that I guard the house, since she had read about burglaries committed during funerals. This was the first time I played a watchman role, which would eventually assume many forms.

At lunch after the service, Lee Eastman asked if I would help Anni with everything that had to be done concerning Josef’s estate. We were in the Alberses’ living room, eating Josef’s favorite foods, including Westphalian ham and black bread, and vinegary as opposed to mayonnaisy potato salad—Anni had specified this—all of which I had picked up at the family-owned German store where I had often gone during the previous couple of years to satisfy Josef’s culinary nostalgia. He was sentimental about little else, but words like rheinische appfelkraut (a sweet apple butter) and certain “wursts” made him light up with pleasure.

17. ANNELISE ALBERS, design for Smyrna rug, ca. 1925. As her work developed, the artist broke away from symmetry to create exceptionally dynamic compositions.

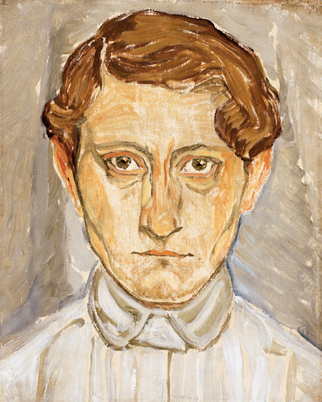

18. JOSEF ALBERS, Mephisto Self-Portrait, 1918. Josef enjoyed comparing himself to Mephistopheles, but Anni was so bothered by this image that she denied he could have painted it.

19. JOSEF ALBERS, Untitled, 1921. When he could not afford traditional art supplies, Albers went to the town dump in Weimar and hacked up bottle bottoms and other glass fragments, which he then assembled into luminous and vibrant windows.

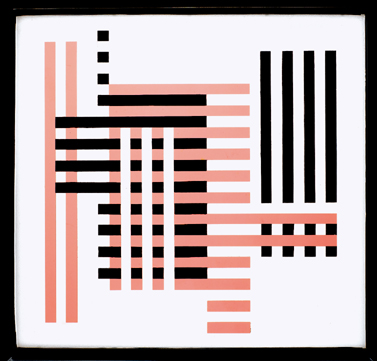

20. JOSEF ALBERS, Bundled, 1925. Once Albers began to use sandblasting, he made glass compositions that took geometric abstraction into completely new territory.

21. JOSEF ALBERS, Red and White Window, ca. 1923. Albers’s window for Gropius’s reception room at the Weimar Bauhaus gave visitors a sense of the warm optimism that pervaded the school at its best.

22. ANNI ALBERS, design for a rug for a child’s room, 1928. Albers designed a rug that gave children spaces for their toy soldiers or dolls or checker pieces. The concept of play was vital to her.

23. The Alberses’ house at 808 Birchwood Drive, Orange, Connecticut. The house where Anni and Josef ended up at the conclusion of their lives was startling in its starkness and ordinariness, yet it served their needs perfectly and honored their values.

24. ANNELISE FLEISCHMANN, wall hanging, ca. 1923. Fleischmann’s first wall hanging was an astonishingly bold and simple abstract composition.

25. ANNELISE ALBERS, wall hanging, 1926. Albers avoided repetition in her compositions, yet maintained a clear number system and limited her elements and colors. Considering this her finest work to date, she gave it to her parents. They put it on the grand piano, where it was damaged by a damp vase of flowers that left a permanent circular stain halfway down on the right-hand side.

26. ANNI ALBERS, Bauhaus diploma fabric, 1929. At the request of the director of the Bauhaus, architect Hannes Meyer, Albers developed a wall covering for an auditorium that absorbed sound, because of qualities on the back, and reflected light on its visible side. Its shimmering materials and careful composition, candidly revealed, lend visual beauty at the same time as they perform their functions. Albers was awarded her Bauhaus diploma on the basis of this piece.

27. ANNI ALBERS, Fox II, 1972. This image came out of the process of printmaking and was the accidental result of the way a photographic negative fell on top of a Velox. Albers relished the idea that she could never have anticipated or made studies for these rich results.

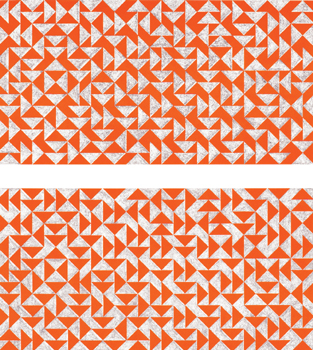

28. ANNI ALBERS, Fox I, 1972. Fascinated by the technology of photo-offset, which she had never before tried, Albers enjoyed reversing an image and reproducing her hand-drawn pencil strokes in juxtaposition with the opaque red ink.

29. ANNI ALBERS, Six Prayers, 1966–67. Albers’s memorial to the six million Jews killed in the Holocaust is among her most moving works, evocative of intimate human lives, full of palpable connections, and seemingly audible.

THE NEXT WEEK, at Anni’s suggestion, I began to use the desk Josef had in the basement of their house, in a little office off his studio. The design of the desk was the same as that of the cherry version upstairs, but the materials could not have cost more than fifty dollars. The eight-foot-long top was constructed from the same Masonite Josef used for his Homage to the Square paintings—while he painted on the rough side, here he had the smooth side faceup—with the bottom a second piece of Masonite, on stovepipe legs. Josef had shoved everything from writing paper to train schedules into the four-inch-high space between the top and bottom. For many years, I continued that practice.

In about 1985, I was looking for a list I had made long before of some of Josef’s paintings. I ended up emptying out the space that held a mélange of his and my paperwork. Way in the back, I found a carbon copy of a typed letter composed in German on a manual typewriter. The paper was a fragile onionskin, but it had survived.

It read:

Minutes of the conference of July 20, 1933.

Present: Albers, Hilberseimer, Kandinsky, Mies van der Rohe, Peterhans, Reich, and Walther.

Mies van der Rohe reports on the last visit with the county board of teachers and on the accounts which the investigating committee gave in Dessau newspapers. In addition, Herr Mies van der Rohe informed the meeting that it was possible to terminate the lease effective July 1, 1933, but that despite this the economic situation of the Institute, because it had to be shut down, was in such poor condition that it was impossible to think of rebuilding the Bauhaus.

For this reason, Mies van der Rohe moved to dissolve the Bauhaus. This motion was carried by a unanimous vote.

Following the review of the financial situation, Mies van der Rohe announced the agreement which had to be made on April 27, 1933, with the firm of Rasch Brothers. Herr Mies van der Rohe intends, however, to negotiate further with Mr. Rasch, in order to see if he can get another payment to help settle the debts.

If at a later date the financial situation should improve because of the royalties from the curtain materials, for example, Mies van der Rohe will try to pay the members of the faculty their salaries for the month of April, May, and June 1933.

(signed) Mies van der Rohe 77