The change began when Ludwig Mies became even more fascinated with the new and radical ways of seeing that he had first experienced with Mrs. Kröller-Müller. “De Stijl,” “constructivism,” and “dada” were all in the air in Berlin, and Mies met some of their practitioners. Hans Richter, an abstract artist who was two years younger than Mies, was the catalyst in getting a number of the leading artistic adventurers to meet one another. Richter, who came from a wealthy Berlin family, had joined the dada movement in Zurich. He made experimental films, and believed that artists should actively oppose war and support revolution. Through him, Mies came to know Theo van Doesburg, Hans Arp, Tristan Tzara, Naum Gabo, and El Lissitzky, and began to see them regularly.

Mies was drawn primarily to the wish of those artists to purify and simplify visual experience and to get to the essence of things. Their approach was the opposite of expressionism, the other dominant trend of the time, with its deliberate revelation of personal emotion. The young architect enjoyed the artistic cross-pollination that occurred through his exposure to other brilliant people; even if their styles were by no means identical, a lot of mutual learning was possible. For the first time, he was discovering that it was not just pleasant to be with like-minded souls, but that it was deeply informative. Part of what would lure him to the Bauhaus, which he would frequently visit before becoming its third director, was another version of the creative camaraderie that Hans Richter had helped him discover in Berlin.

IN THIS PERIOD when he was listening eagerly to dadaists and constructivists with their attitudes ranging from nihilism to positivism, Mies’s own views were reflected in the writing of Oswald Spengler, whom he read with the sense that he was facing his own truth. In his book The Decline of the West, Spengler proffered the theory that European civilization was in its “early winter.”8 Rather than deceive ourselves about the painful reality of that approaching demise, it was necessary to face it squarely.

Mies also confronted the hard truth of his home life. At the end of 1921, Ada and the three girls, all under the age of seven, moved to a separate apartment, in Bornstedt, another Berlin suburb. Ada was in a deep depression. She remained devoted to her husband, but they felt they could no longer be together all the time.

At first, Mies spent most weekends with her and their daughters. Given the unusual circumstances, they were surprisingly like a traditional family during those visits. But soon he began to show up with less frequency, and started to restructure his life. He turned the dining room of the former family home into his workspace, while moving his bed into the capacious master bathroom—the actual toilet was behind a door—and using what had been his and Ada’s room for guests. It was no longer a space to which his wife and children could return.

Then Maria Michael Ludwig Mies engineered a new name for himself. In May 1922, a reference to his work in an important architectural review said it was by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The son of Michael Mies and the former Amalie Rohe had dropped Maria Michael and, while he could not entirely shake off the discordant Mies, had softened its impact by following it with his mother’s maiden name and dressing it up with the sonorous, and seemingly grand, “van der.” He even added an umlaut over the e of Mies, in an effort to shake off its grimy connotations, but that maneuver did not stick. “Roh” means “pure,” a nice antidote to the nastiness of the “Mies” he hoped to vitiate with the umlaut, and the ensemble had a pleasing flow. In addition, the new appellation seemed Dutch, because of the choice of “van” rather than “von,” in keeping with the tastes he had developed in working with Mrs. Kröller-Müller.

He would, regardless, be referred to and known as Mies. That practice is followed in this book, even though Dorothea, who was calling herself Georgia van der Rohe when I met her, instructed me, her finger waving, “Never ever just say ‘Mies,’ which means something quite wretched; my father’s name was ‘Mies van der Rohe,’ always with all of it.”

Ada put their three daughters in a new academy that Isadora Duncan had just launched in Berlin, but it soon became clear to her that their old way of life would never be restored, and in 1923, she took off with the girls for Switzerland. It was the final break in their family life. The mother and the three children would move from place to place for over a decade; Mies would live his life apart from them, although never divorcing—in part because he could not afford to do so financially.

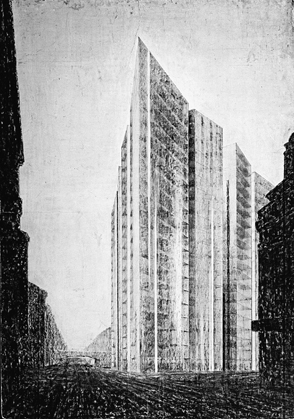

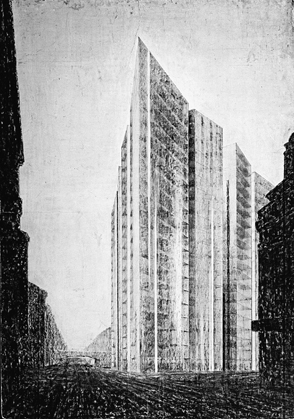

LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE also took on a new identity as an architect. He made a design for a triangular skyscraper, sheathed entirely in glass, that soared like a crystal prism. While it resembled an imaginary edifice in a science-fiction movie, it was very real in the clear exposure of its structure. It invited a new way of seeing that disguised nothing and celebrated recent technological advances. The focus was on up-to-date materials and construction methods, and unprecedented ideas of how things might look, with a scrupulous avoidance of anything personal. Mies was already rallying to many of the same principles that were being celebrated and explored at the Bauhaus. While he had no real connection to the school as yet, he was well aware of what Walter Gropius, the elegant and well-heeled young man he had encountered in Peter Behrens’s office, had recently started in Weimar.

Ludwig Mies, Friedrichstrasse skyscraper, perspective view from the north, ca. 1921. Mies’s skyscraper designs looked like cinematic versions of the future.

He then conceived a second skyscraper, also made in shimmering glass, but this time the thirty stories were translucent columns. The overall impact of the scheme is of undulating curves that resemble an updated, space-age version of the portico of the Parthenon—as if the noble form of the temple on the Acropolis has now gone organic. The plan of each floor looks like a marvelous butterfly with fluttering wings; a minimal, delicate core housing two circular elevators with stairs twisted around them is the linchpin of the amorphous form.

There was no doubt that Mies, however frosty or contrived his persona, was someone of incredible imagination as well as tenacity. The designer of this second glass skyscraper clearly believed that anything was possible in the realm of building. His spectacular inventiveness, which he skillfully paired with the advances of modern engineering, opened a new world. Mies as a man began to soar and expand like his building designs. In 1919, he had joined the Novembergruppe, named for the month when the Weimar Revolution occurred. That radical organization had goals similar to those of the Bauhaus: a new closeness between artists and laborers; and the unity of art, architecture, city planning, and the crafts. One of its intentions was to open the common man to the groundbreaking modernity that was in the air after the war. The other members included Lissitzky, László Moholy-Nagy, the composers Paul Hindemith and Kurt Weill, and the dramatist Bertolt Brecht. Unsatisfied, ever, to be merely a member of an organization, in 1923 Mies became the Novembergruppe’s president.

At this time, he was also spending more time with Kurt Schwitters and Hannah Hoch. These brilliant “dada” artists were an inspired choice as friends, for they endowed their groundbreaking, seemingly random, abstract compositions with sublime artistry. Even if Mies could not fully embrace Schwitters’s and Hoch’s emphasis on spontaneity and chance, he, too, envisioned a form of liberation. His mission was “to free the practice of building from the control of aesthetic speculators and restore it to what it should exclusively be: Building.”9

Mies was adamant that the purpose of a structure must govern all decisions; any preconceived notion of what something should look like was a folly that had to be avoided scrupulously. “We refuse to recognize problems of form, but only problems of building. Form is not the aim of our work, but only the result. Form, by itself, does not exist.”10 He made this declaration in the new magazine G, started in 1923 by Richter, Lissitzky, and Werner Graeff. Mies’s bold design for a concrete office building—it resembles a modern multilevel car park of the type that proliferates today in cities all over the world—was also in the magazine. It was tough and absolute, and as didactic as his words.

THEN THE NEW Herr Mies van der Rohe began to demonstrate the quiet elegance that would be his forte. When he applied his strict approach to private residences, the complete absence of adornment, and the crisp right angles and bold forms, led to ineffably graceful results. Mies’s idea of building from the inside out, reversing the traditions of domestic architecture that had ruled the western world ever since the Renaissance, inspired designs of balletic grace.

Mies had a gift that went far beyond all of his theories and statements: he had a guiding eye that was the equivalent of perfect pitch in music. He infused his assemblages of concrete or brick blocks with a rhythmic motion and overarching grace that made them come alive.

The young architect transformed weighty materials by combining them in such a way that they miraculously produced a fluid movement within a balanced whole. He was like a master musician who uses an instrument that is primarily wood or metal to create flawless sequences of mellifluous sounds. Mies’s concrete country house of 1923 and his brick country house of 1924, while never realized, remain, in their drawings and models and plans, creations of breathtaking beauty. Based on no architectural precedent, deriving only from Mies’s own ideas of how to align walls and juggle rooftops and use the most straightforward modern materials to create magical spaces, they are both splendidly animated and imbued with a look of tranquillity. In other hands, similar concepts might have been harsh; in his, they are refined. In the concrete villa, the few openings and occasional short flights of exterior steps in the otherwise bunkerish whole invite a sense of dreamlike events. In the residence in brick, with its long retaining walls and massing of blocks at the core, the marvelous placement of translucent walls amid the solidity of the rest provides sheer delight.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, concrete country house project (view of model), 1923. In the same year that he dropped his given first names and added the soigné “van der Rohe,” Mies invented completely original forms of human habitation.

The man himself was cold, forbidding, and ambitious; his architecture was warm and welcoming. What the building designs have in common with the person who made them is that they prove that refinement is not a matter of the elements with which one starts out, but of what one does with them. They show that structural materials can be as elegant as they are rough.

The brick in country houses went back to Georgian architecture in eighteenth-century England, but in that instance the desire was to minimize the rawness of the material and encase it in ornament. Mies’s brick country house is the opposite. It is simply a sequence of freestanding brick walls, of various heights and lengths and thicknesses, some of them meeting at T-junctions, others joined at right-angled corners. With no doors, it is one continuous flowing space. Full of surprises, with a concentration on the human experience, the conglomerate alternates nooks and crannies with larger spaces. It accommodates the human need for both coziness and generosity of scale. It and the concrete country house, with their exquisitely refined designs based on ordinary materials, presented a new notion of a suitable shell for human existence. With their open plans, they would have lasting influence on domestic architecture worldwide.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, brick country house project, 1924. In elevation and plan, his brick country house had rhythmic interlocking forms and extraordinary spatial flow.