I was with Anni Albers in September 1980 when she received a phone call saying that Nina Kandinsky had just been murdered.

The person on the other end of the line was Tut Schlemmer. All three of these women—Nina, Tut, and Anni—were now widows. Anni had had nothing to do with Nina since Kandinsky’s death; there was no feud, but she and Josef felt no real connection with her. A letter they had received from the Kandinskys in 1935 summed up the problem. Wassily had complained for fourteen handwritten pages about the hardships of making his way in Paris: “Neither the public at large nor the beautiful people show the least interest in art.”1 At the bottom, Nina had scrawled an ecstatic addendum. At a ball given by a Russian grand duke, she had worn a magnificent gold lamé gown and danced a Viennese waltz with a prince: “I would have loved, dear Albers, to have danced with you.”2

Anni had often cited that letter as an example of who Nina really was. Regardless, the news of Nina’s violent death flabbergasted her.

TUT EXPLAINED to Anni that she had gone to Nina’s villa in Gstaad, the Esmeralda, for a dinner date, and that no one had answered the door. She rang and knocked for nearly five solid minutes. Finally, she went to the nearest telephone and summoned the police. When they broke in, they discovered that Nina had been strangled.

Tut, who had been in Nina’s chalet a number of times, was pretty certain that none of Kandinsky’s paintings were missing. Everything was where it was supposed to be. And she knew that Nina kept most of her jewelry in the bank vault. But eventually it was discovered that Nina’s latest diamond necklace, valued at almost a million dollars at the time, was gone, as were some other items.

Anni, who favored Mexican clay beads, was fascinated with Nina’s taste in jewelry. A couple of years earlier, a curator from the Guggenheim Museum had described Nina at the Carlyle Hotel getting ready to go to the opening of a Kandinsky show. Anni, remembering how broke most everyone in Weimar and Dessau was in the 1920s, and having personally considered the Bauhaus an escape from the ostentation that prevailed in the Berlin of her childhood, was intrigued as she heard about Kandinsky’s widow going through a jewelry box that was like a treasure chest trying to decide whether to wear emeralds or diamonds or rubies around her neck that evening, and then addressing the question of which earrings to wear, and which bracelet and how many rings of precious stones. After Kandinsky’s death, the price of just one of his paintings had skyrocketed to a higher value than all that the artist had earned during his lifetime. With her new fortune, Nina had become so well-known for her million-dollar jewelry habit that Van Cleef & Arpels and Cartier vied for her patronage.

When the Bauhaus was in Weimar and Dessau and Berlin, the main issue had been survival; Kandinsky had been excited when he could finally buy new shoes. And those conditions had been an improvement over the earlier period when the Kandinskys’ toddler son died from malnutrition. No one could have imagined that there would someday be a group of Bauhaus widows who would be among the most powerful figures in a money-driven art world, or that Kandinsky’s former housekeeper would be a millionaire. But all this had come to pass. After Kandinsky’s death, the Paris-based art dealer Aime Maeght had “no problem worming his way into [Nina’s] confidence” and had encouraged her to spend freely—to enjoy herself for a change. This was observed by the pithiest of commentators on the worldly side of artists, John Richardson, who wrote:

The more she splurged, the more art she was obliged to sell, and the more Maeght profited. After all those years of hardship, why shouldn’t she treat herself to a car and driver and clothes from Balenciaga? Since she was Russian, why shouldn’t she play lady Bountiful with the vodka and caviar and wear a sable coat? And why, above all, shouldn’t she indulge her as yet unindulged passion for jewelry? Rubies, sapphires, above all emeralds reminded her of Kandinsky’s resplendent sense of color. … “Van Cleef & Arpels are my family,” Nina would declare.3

Anni and Tut chatted briefly about their new lives as managers of important artists’ estates. “We have something called ‘a foundation,’” Anni explained, as they discussed the irony that, having once been nearly destitute, they now spent so much time with lawyers and accountants and tax experts trying to manage the good fortune that had come their way in recent years. She also told Tut about recent and upcoming exhibitions of Josef’s and her work, although she was not boastful, and still acted as if the recognition that was Josef’s due had not fully arrived.

She and Tut agreed to stay in closer touch, and Tut promised that if anything more was discovered about the circumstances of Nina’s death, she would let Anni know.

THE MURDER OF EIGHTY-FOUR-YEAR-OLD Nina Kandinsky has never been solved. But I was with Anni a month or so after the call from Tut Schlemmer—who never phoned again, because there was nothing substantial to report—when she had a conversation about the crime that fascinated her. John Elderfield, who was then curator of drawings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and was working with me on what was to be an interdepartmental Josef Albers retrospective there, had come to Connecticut so we could look at Josef’s unknown work together. Anni, however, was not so interested in Josef’s show as in what she might learn further about the strangling in Gstaad.

Elderfield, in his buttermilk voice and North-of-England accent, smiled mischievously and told her, “There’s a rumor that Felix Klee did it.”

“Nein!” Anni answered. But she was excited at the prospect, even as she and John Elderfield concurred that of course it was impossible.

FROM TIME TO TIME, Anni would mull over these events in her head. Could Felix have done it? Of course not, but there had been a lot of animosity when he remained in Germany after all the Bauhaus masters had left. Felix as a little boy had been so close to Kandinsky, even before Nina was on the scene, and then the two families had shared that house next door to the Alberses’ on Burgkuhnauer Allee in Dessau; could there have been something that went on that no one knew about?

After the Bauhaus closed, the Alberses had grown apart from most of these people. They had exchanged warm letters with Klee, but he died before the war was over. Josef and Kandinsky had stayed in close touch throughout the 1930s—Albers had even tried to get him to Black Mountain, and Kandinsky had organized and written about a show of Josef’s work in Milan in 1934—but Kandinsky, too, had died before there was any possibility of the Alberses visiting Europe again. They saw Mies a couple of times in Chicago, in spite of Josef’s views of the cigars and gin fumes, but Mies was never someone to whom one could be close anyway. When he died in 1969, the Alberses were aware that there was no one to whom they could write a condolence note.

A dance at the Dessau Bauhaus ca. 1926. The couple in the lower right is Nina Kandinsky and Josef Albers. In 1935, when the Kandinskys were in exile in Paris and the Alberses were in the United States, Nina wrote, after a fancy dress ball, “I would have loved, dear Albers, to have danced with you.”

Gropius, who died the same year as Mies, was the only one with whom they maintained a professional connection. The Alberses had both worked with him in 1950 on the Harvard graduate center. Josef designed a brick fireplace for one of the public spaces there; it has a subtle abstract pattern made through the various angles at which white bricks were set in mortar. Anni created woven room dividers and bedspreads in bold abstract patterns—they bear a remarkable resemblance to what would become the trademark lining material of Burberry raincoats—that added considerable panache to the students’ lives. Josef also made a mural in the early 1960s for the Pan Am Building; called Manhattan, it was installed over the escalators that took 25,000 people a day to and from Grand Central Terminal. It was based on one of his Bauhaus glass constructions, yet it conveyed the liveliness and energy he and Anni discerned in New York the moment they arrived there after leaving Nazi Germany.

Except for the time when Ise had embarrassed Anni about the pearls, the Alberses had not seen the Gropiuses socially. And while Josef maintained a connection with Marcel Breuer, the friendship ended completely after a feud erupted because Josef felt that Breuer had taken one of his designs—for an abbey in Minnesota of which Breuer was architect—without giving him proper credit. Josef often broke off from people definitively, even as Anni tried to be the diplomat and work with mutual friends to achieve a rapprochement.

With their savior Philip Johnson, however, neither of the Alberses cared about maintaining the connection, even after Johnson gave Anni her exhibition at MoMA; they were too appalled by his betrayal of modernism and his embrace of historical forms. Equally important, the Alberses considered Johnson a socialite, not a dedicated artist of the sort they had known at the Bauhaus. He may have been the person who engineered their getting out of Germany at the best possible moment, but his affinity for rich and chic friends was more than they could tolerate. This was most apparent when he invited them to the Glass House in New Canaan for Sunday lunch and served them leftover meatloaf from a dinner party for “more important people” the night before: an offense they never forgave.

After Josefdied, and when Anni was suffering too much from dementia to understand more than the simplest ideas, I had a moment with Philip that made it easy for me to understand the rift. Philip was graciously showing me his art collection, which was in storage in a gallery space on the grounds of the Glass House. First of all, the style of the building would have set Josef’s hair on end. Then, when Philip was pointing out a large painting by Jasper Johns, I said to him, far more politely than Josef would have, that while I recognized that many people considered Johns a major artist and that the early painting Philip was showing me on a storage rack was of particular interest to people who prized his work, I simply did not like Johns’s art. Philip smiled and quickly responded, “Oh, neither do I. It’s just that Alfred told us we all had to buy them, and we did whatever Alfred recommended.”

Philip looked very pleased as he said this. He took a cynical delight in pointing out that the reasons for which rich people acquired expensive art rarely had to do with their own taste. On another occasion, he was delighted to tell me that Eddie Warburg had bought an important 1905 Picasso portrait of a young boy because the youth was so good-looking: “We all had such a crush on that boy, Lincoln [Kirstein] and Eddie and I.”

Philip Johnson’s quips were antithetical to the Bauhaus spirit. People like the Alberses and Klee and Kandinsky never let anyone else dictate their taste; they held artistic quality to be the supreme issue. And for Josef Albers, the idea of Alfred Barr—Philip’s “Alfred”—as the voice of authority was an impossibility. Josef told me that he felt that Barr had never forgiven him for being part of a group of artists who, in the mid-1930s, stood in front of the Modern to protest its lack of attention to purely abstract artists. Josef was among the few people who questioned Barr’s criteria for what great art was, and who was willing to say so. Philip, in letting himself be swayed—and, beyond that, in his Oscar Wilde—like embrace of his own fickleness—took pleasure in what he considered his moral corruption (his favorite line about himself as an architect was “I’m a whore”), while the Alberses, Kandinsky, Klee, Gropius, Mies, and a number of other people at the Bauhaus considered aesthetic standards inviolable.

EVEN THOUGH ANNI had not stayed in touch with Nina Kandinsky, she still thought of her as part of the extended family. Silly as Nina was, she had made it possible for a genius to live and to paint with far more ease and comfort than he would have known without her. And Nina belonged to the golden age. Anni was always fascinated to learn the latest gossip about this woman who had amused her and Josef and their more serious colleagues in Weimar and Dessau. Hearing about Nina was like reading a magazine at the hairdresser’s. She was well aware of the contrast between Kandinsky’s marriage and Josef’s, and knew full well that, while Josef would not have married a coquette who knew little about art, he still had a hankering for some of Nina’s frivolity.

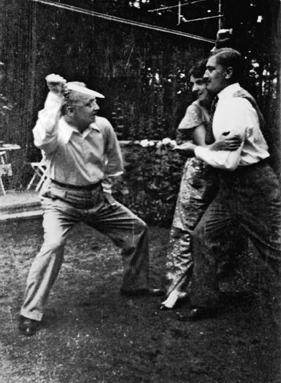

Josef Albers and Nina and Wassily Kandinsky, ca. 1930–31. For all the seriousness of their devotion to making great art, the Bauhauslers also applied their imagination to having a good time.

Anni was intrigued when she learned that Van Cleef had made Nina a parure that consisted of a necklace with a 20-carat diamond pendant, a bracelet, earrings, and ring. It had different colored diamonds that resembled a variety of colored drinks: Remy Martin, chartreuse, Lillet, and Dubonnet among them. Nina was so scared of crime that she used a code number rather than her name in dealing with the jewelers, yet she was photographed wearing the parure when she was given a Legion d’ Honneur by the French minister of culture, the same year that Josef died, and she had called her chalet Esmeralda after her favorite stone. Anni also enjoyed hearing about Nina’s flirting with young men, in part because she felt superior because she had Maximilian and therefore did not have to do the same.

Nina had written a gossipy memoir that no one bothered to read; Anni had been given a copy, but did not make it past the first page. The most entertaining detail, which in Anni’s eyes summed up the whole silly undertaking, was that Nina had wanted to call it I and Kandinsky until Heinz Berggruen persuaded her to go with Kandinsky and I.

QUITE SOME TIME AFTER Tut Schlemmer’s phone call and John Elderfield’s visit, Anni was particularly interested by some details she learned about the connection between Felix Klee and Nina in the last days of Nina’s life. Felix had dined with Nina on September 1, 1980, the night before she died, an occasion at which Tut Schlemmer was also present. There was so much borscht and beef Stroganoff left over that Nina had invited them back the following evening.

That was the evening when the police found Nina’s tiny corpse on the bathroom floor. She had been strangled by bare hands.4 If there were fingerprints, they were never discussed in any accounts of the crime. There was no sign of anyone having broken into the apartment. A package of the powder florists include with bouquets was sitting on a table, but there were no flowers; this may or may not have indicated that someone arrived with a bouquet and then left with it, perhaps because it would have been a clue to the crime. Jewelry worth more than two million dollars was gone.

There were only fourteen people at Nina’s funeral when it took place a few days later in Paris. None of them, it seems, felt it necessary to push the case to a conclusion.

Kandinsky had always said that it was impossible to solve the mysteries of life. The few characters on the upper tier of the pyramid he describes in On the Spiritual in Art are the rare human beings who accept that the fortress of knowledge is impregnable. Could he have imagined that his wife’s death would require that same resignation?