Bodies Piling Up. Snow Piling Up. But Where to Place the Blame at Brookhants?

It’s now past time that I pull you back to 1902, Readers, to the angel’s trumpets and glass of the Brookhants Orangerie, where Eleanor Faderman still lay dead and gripping the once-missing copy of Mary MacLane’s book. The copy now again accounted for.

And oh had it ever been accounted for. The unlucky students who found Eleanor had already told their classmates about it, which meant the whole of the school knew. Now, while they waited for help to arrive from town, most of the faculty had come to see for themselves. In fact, a few of them seemed almost as concerned about the presence of the book as they did the body.

And it was up to Principal Libbie Brookhants to do something about that.

Do it now, she told herself. Take it from her now before someone else does, before they all notice. And talk.

Principal Brookhants stood in a swarm of her colleagues, still gathered near—but not too near—to Eleanor’s body. A few were even standing atop the bitten blooms. Some were weeping. All were stricken with horror. Around them fogged the cloying scent of the angel’s trumpet at night.

You must do it now, Libbie told herself, sliding around Miss Lawrence and closer to Eleanor.

Libbie Brookhants was still a relatively young woman and looked it in the flush of her cheeks and the shine of her gingerbread hair. There were, it’s true, the beginnings of crow’s-feet at the edges of her eyes, but only the beginnings. She still looked young enough to be mistaken, on occasion and from afar, for one of her students.

What’s more, she felt young, felt it acutely in moments like this one, with so many other women waiting for her judgment and instruction. She was the youngest of her many siblings, all of them brothers with a surname to uphold. Or better yet, outdo. At the age of twenty-two, she’d married a very old man only to almost immediately become his very young widow. And for the last eight years, she’d been the young principal and proprietor of this school, her school: the Brookhants School for Girls.

“I can’t think how we’ll go on now,” Miss Larson was saying to Miss Hamm as Libbie managed to position herself behind Eleanor.

“We can’t and we won’t,” Miss Hamm said. “It would be indecent to. It’s indecent to even be gathered here.”

Libbie didn’t disagree. She was now within reach of the book, if only she could bend down to retrieve it. But even as they pretended to look away, she could feel the eyes of her colleagues upon her. They were watching her, waiting to remark upon her handling of this moment, waiting to catch her out and place the blame for this—and for Flo and Clara, too—squarely at her feet. Perhaps she should let them. Close the school and . . .

And what? What then?

Libbie had been crying. She’d stopped, now. Mostly. But the water in her eyes bubbled her vision. It made her almost seasick: the crimson book below her puffed like sailcloth and the crowd of grim faces before her as warped and strange as gargoyles stuffed into shirtwaists. All except for Miss Alexandra Trills. Alex, her Alex*—a head, two heads, in some cases—taller than any of the other women in the room and as familiar as ever, even now. Libbie wiped her eyes and held them to Alex’s own until she felt them lock together in silent conversation.

Miss Trills and Mrs. Brookhants were suited to this kind of intimate exchange because of the intimacy of their relationship. It was an intimacy known, while also sometimes deliberately or ignorantly misunderstood, by their colleagues. In the language of the day, Mrs. Brookhants was a young widow and Miss Trills was her devoted companion. Her very, very dear friend. Her confidante.

Her bestie.*

However, Miss Trills and Mrs. Brookhants had no time to find much comfort in their friendship on this night. At least not in this moment. In fact, perhaps it was only more fuel to the fire. For when, emboldened by Alex’s presence at the back of the crowd, Libbie carefully knelt to retrieve the book, the music teacher, Miss Hamm, struck like a coiled serpent:

“And so what is your excuse for it this time, Mrs. Brookhants? Or will you now finally condemn it?” Miss Hamm pushed her way to the front of the unhappy group. She was both the most doctrinaire and the most dramatic of the Brookhants faculty. She pointed a finger at the book as if she were on the witness stand and had been asked to indicate to the court the presence of a murderer. Leanna Hamm did love an audience. “There’s a known wickedness in that book and our girls won’t leave it alone. I don’t think they can. I don’t think they want to.” She spoke this last bit with hushed alarm lacquered over her words.*

The group looked at Libbie for her response. She had not yet removed the book but was still kneeling to do so. She gathered herself before speaking. “We’re all as devastated by this as you are, Leanna. But I won’t pretend the devil himself lives in this book.” She used this as her cue, it was as good as any, and lifted the book from Eleanor’s grip. She was very gentle.

Even still: a few teachers gasped or turned away. But not Miss Hamm.

“It’s every bit as real a culprit as a knife or a jar of poison. It is a poison!” Miss Hamm was now sniffing in indignation. “It poisons the mind.”

“The flowers Eleanor ate are the only poison here,” Alex said as she moved nearer to Libbie.

“And why did she eat them?!” Miss Hamm asked as if Alex had proved her point rather than countered it.

“They were all in that club,” Miss Cullen said quickly, hoping to egg on Miss Hamm, which was Miss Cullen’s way. “We had that group of them reciting it: Kind Devil this and Kind Devil that.”

“Eleanor Faderman was never in that club,” Alex said. “She wouldn’t have been asked.”

Miss Hamm ignored her. “I said at the time we shouldn’t allow it on campus—the book or their awful group.”

“And certainly forbidding something has never before encouraged our students to pursue it,” Libbie said. She now held the book—as casually as possible, given the circumstances—against the folds of her skirts. Alex, ever perceptive to her Libbie’s unstated desires, moved carefully alongside her and took the book from her hand, holding it low against her side, then her back.

“They would go out into the woods, remember?” Miss Hamm said, her excitement mounting now that she sensed others were backing her up.* “And come back feral and rude, full of bad ideas.”

“But that isn’t the same copy, is it?” someone asked from the back. “It’s not the copy we found with Florence and Clara?”

“That copy was previously disposed of,” Libbie said firmly. This was a lie.

“At least there’s that,” Miss Lawrence said.

“You’re certain?” Miss Hamm asked in side-eye. “I understood it to be lost. That’s what we were told—that’s what Clara Broward’s own mother was told.”

“I am very sure,” Libbie said. She softened some. “There is more than one copy of this book in existence.”

“It broke sales records, didn’t it?” Alex said. “For weeks it was everywhere.”

“And what a poor commentary on the state of things that fact is,” Miss Hamm said.

Libbie tried to speak now with the firm authority of her position. “If any of you would take the time to read it,” she said, looking pointedly at Miss Hamm, “as I have, you would know that it’s primarily the purity of feeling expressed that our girls are responding to. The author is about their age and so earnest in her passions, so forthright and unabashed. She seems to them like someone who could be their bright-brash friend. Some of our girls even seem to think they could be her.”

“Heaven help us if that’s true,” Miss Hamm said.

“Why don’t we help ourselves instead, Leanna?” Libbie said. “I think we’re quite capable of it. The book is nothing more than a young girl’s diary.”

“Nothing more than a diary?” Miss Hamm scoffed. “Let me ask you, Mrs. Brookhants, did your childhood diary cause a group of girls to make a suicide pact in”—she turned to Miss Mercado to ask—“where was it that I told you?”

“St. Louis, I think it was,” Miss Mercado said, like she was hoping for a gold star.

“I did not keep a diary as a child,” Libbie said.

Miss Hamm ignored her, playing to her crowd. “And now they’ll be telling the same stories about Brookhants and our girls. And they should!” She turned again to Libbie. “We’ve all granted you considerable room to test convention here, Mrs. Brookhants. Time and again I’ve said nothing, even when I thought your educational methods dangerously liberal. Slipshod—”

“Now, Leanna—” Miss Mercado tried to slow her, but Alex was more forceful.

“You’ve granted Mrs. Brookhants nothing, Miss Hamm,” she said. “Not one thing. It is simply not in the realm of your authority to do so.”

Now Miss Hamm was spitting her words. “Since coming here, I’ve excused the goings-on at this school more times than I can count. I’ve made excuses for every sort of accusation imaginable—the things I’ve excused—but you can be sure that I will do it no longer. And I will not be told that a bad book is a good one and pretend to agree.” She gathered herself again. “We’ve failed these girls. Three deaths and we’re to blame. How many more will it take?”

“I don’t—” Libbie began, but again there was no point. Leanna Hamm was too competent a performer to give away the last word.

“I feel very unwell and am going to bed now,” she said, pushing her way back through her colleagues. A few of the others said and did similarly. But only a few. The crowd reshuffled around Libbie, awaiting their instructions.

“I don’t feel as strongly as Leanna does about that book,” Miss Lawrence said. “But it does seem to me, at this moment, rather foolish to waste your breath as its defender.”

“I wasn’t defending the book,” Libbie said. “I was defending reason against superstition.”

“I’m sure that’s what you believe you were doing,” Miss Lawrence said. “Even still, what will you do with the copy you took from Eleanor?”

“I’ll take care of it,” Libbie said. “It won’t be seen here again.”

She meant this.

Much later, once various officials had arrived and questions had been asked and answered—answered primarily by Libbie Brookhants and without any mention of the book—and after Eleanor’s body had been examined by the physician and collected by the undertakers, and after a decision had been made to cancel regular classes for the following day to allow the students the time needed to reflect and begin their mourning, the remaining faculty members, in puff-eyed pairs or groups, also left for their beds. It was now well after midnight and there had been considerable talk of the weather turning bad.

“I think we should stay here tonight,” Libbie said when she and Alex were finally alone in The Orangerie. “Whatever’s left of tonight.” Through the windows they might have seen their carriage waiting, but Libbie wasn’t looking through the windows. Instead, she was staring at the place where Eleanor’s body had been, so many bitten blooms still smashed there. “These need to be removed before morning,” she said, swirling some around with her foot. “Or girls will be gaping at them.”

“Collecting them as souvenirs,” Alex said, taking Libbie’s hand. “They’ll be gone. Miss Lawrence said she’d have it done before breakfast.”

“Must we kill the tree, you think?” Libbie asked as she looked up into the branches of the angel’s trumpet. “To stop tongues wagging.”

“Killing it won’t do that. Besides, there are thirty other plants here that would have the same effect. Eaten in this quantity, maybe more than thirty.”

“I don’t want to kill it,” Libbie said.

“Neither do I,” Alex said. “It’s a beautiful tree.”

Libbie looked where Eleanor had been and asked, “What could she have been thinking?”

“I wish I knew,” Alex said. She then lightly pressed her lips to the hand she was holding before pulling it, and Libbie, to her and finding her mouth. It was a kiss given and returned simply, a comforting act of normalcy during a most distressing time.

“You’re asleep on your feet,” Alex said. “Home will be best. We’ll have Caspar bring us back in time to join the girls for breakfast.”

Libbie nodded. She was grateful for Alex’s care, for the routine of it.

And yet: between them thrummed a chord of discontent that reached far beyond the immediate trouble here at Brookhants.

Alex bundled Libbie into her coat and scarf. They were headed, by carriage, to Breakwater, Libbie’s ocean home, which is where Alex would also be spending the night. Indeed, despite her small but private quarters on campus in the Faculty Building, Breakwater—beyond the woods and overlooking the ocean—was where Miss Trills spent most of her nights while she was a teacher at Brookhants, there in Libbie’s bed.* In their bed.

“Do you have the book?” Libbie asked as they were at the door.

“I nearly forgot it,” Alex said. “Thank God you didn’t.” She crossed the room and took it from behind a large watering can where she’d stashed it earlier.

Libbie had to keep herself from grabbing for it as Alex again came close. It is enough, she told herself, that she has it in her hand and it’s coming home with us.

On a clear night, the journey from campus should have lasted about twenty minutes. But now the hour was late, the clouds were thick, and the storm had arrived.

In the cold closeness of the carriage, surrounded by the even colder sound of its wheels squeaking over the snow-packed road, Alex continued to hold the red book between them: their party’s third, and unwanted, guest.

“I wish I’d thought to take this from her sooner,” Alex said, her warm breath creating a fog that would soon mist the carriage windows. “If I’d managed it before the others had noticed . . . This book has only ever been bad for us.”

“Not you, too, darling,” Libbie said. Casually, so casually, she took the book from Alex in her gloved hand and thumbed its pages. “If I had read this as a girl of Eleanor’s age, I would have thought it the whole world. And if I’d known you then, I would have asked you to read it so that we could talk about it being exactly right in all its glinting feeling.”

“You would have told me to read it,” Alex said. “And I would have, to humor you.”

The carriage jerked and they were tossed together, hard, against a sidewall before it was righted—and now no longer moving. Caspar, their driver, shouted his apology. “Hit a drift and they lost their footing.” He was off his perch, down on the ground and talking soothingly in an attempt to settle the horses as he dug at their legs halted there in the snow. “It will have to be the sleigh tomorrow,” he yelled.

That drift wasn’t helping matters, but you should know that the horses were often spooked in this particular patch of road as it cut through the woods—the trees tall and dense on either side, too many of their low branches stretching out to scrape the carriage with a horrid sound like bone fingers finding a coffin lid. And now there was more snow, the flakes sudden and angry.

As Caspar worked, the carriage shuddered with his efforts, and Libbie said, quietly, “You do know that when you say this book is bad, you sound like Leanna Hamm, and that should frighten you very much.”

“I think I am a little frightened,” Alex said. “And it hasn’t a thing to do with Leanna Hamm.” She paused. Considered. “I did not say the book itself is bad.”

“You didn’t?”

“I said this business with the book, the way it keeps turning up in tragedy and the stories they’re telling, already—that’s what will be bad for Brookhants. It already has been.”

“We are Brookhants.”

Alex nodded. But then she said, “And so was Eleanor Faderman.”

Caspar called that he thought he’d solved the problem and he must have, because now they were moving again. They rode in somber silence while the wind howled at them.

That is, until Alex said, “You know, it doesn’t matter if this book is the cause.”

“How can you say if? If it’s the cause? Do you hear yourself?”

Alex shook her head. “What matters now is that people believe it to be.”

“Leanna Hamm believes it,” Libbie said.

“There were others. And tomorrow there will be more. These things build like avalanches.” Alex was not looking at Libbie, but out the fogged carriage window, which she now wiped with the sleeve of her coat. “They start off with a few flakes and gather force, tumbling down and down until they smother you.”

Libbie shook the book at Alex. She’d had enough. “At least Mary MacLane has the excuse of her tender age to account for her theatrics. Tell me, what is yours?” She did not wait for an answer. “No, don’t. I don’t want to talk any more about it tonight.” She looked out the newly clear window and saw the bundled figure of their maid, broom in hand. “What on earth can Addie be doing? She’s mad to be outside in this.”

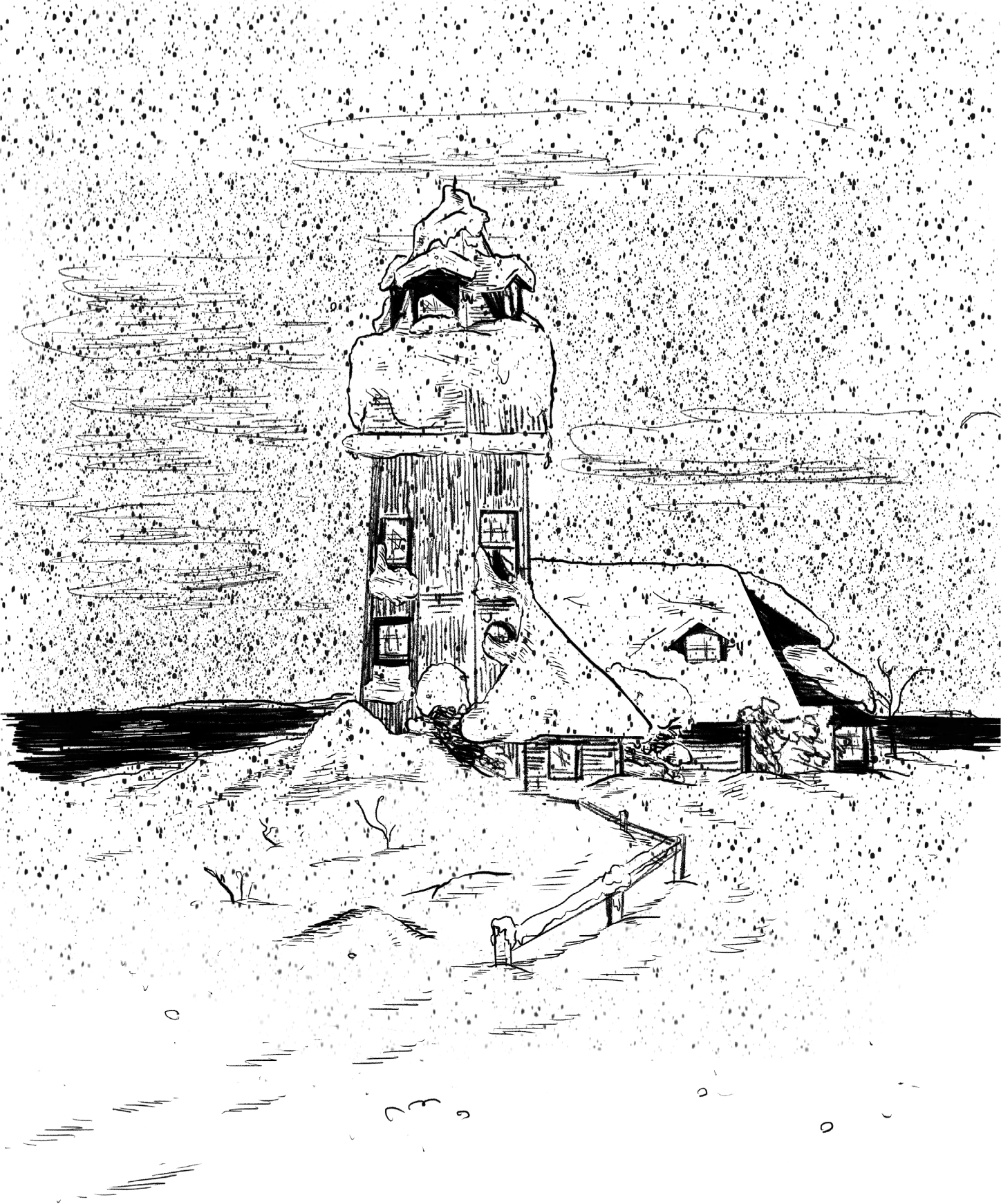

They’d rounded the last bend and there was Breakwater,* the windows at the top of its odd tower lit yellow like jack o’ lantern teeth.

“I’m sure she’s doing whatever she thinks will please you most,” Alex said, watching as the maid finished her final sweep of the porch—it was down to bare wood, for now—and hurried back inside the house.

“Please not that tonight as well.”

“Not tonight or any night,” Alex said as Caspar pulled them up the drive, the still-recent addition of electric porch lights casting yellow egg yolks of illumination across the snowy ground.

Libbie kept Breakwater running with the same minimal staff she’d inherited from her now-dead husband, Harold. Save for large and irregular repairs, and unless Libbie was hosting, it was really only a single family, the Eckharts, who made the house function: Caspar, whom you’ve met and who in addition to driving the carriages tended to the meager livestock and grounds; his wife, Hanna, the head housekeeper and sometimes cook; and their son Max and his new wife, Adelaide, who had recently moved from Harold’s Pittsburgh estate and who took care of all else.*

Perhaps, Readers, this doesn’t seem so small a staff to the presumably staffless you and me, but compared to other members of Libbie’s social set and the personpower required-desired to run their massive mansions across the water in Newport or Jamestown, hers was indeed a skeleton crew. And the truth is: they were all still getting used to the addition of Adelaide to that crew. Even the Eckharts themselves were still getting used to it, but especially Alex.

However small in number, the Eckharts were a capable bunch, and even despite the lateness of the hour, the house was warm and lit when Libbie and Alex pulled in that night. This was especially welcome, because here, at this house of windows, perched, as it was, above the ocean, the wind was terrible—moaning as it crashed the waves and whipped sheets of snow upon the women.

Working with effort against the wind, Adelaide managed to open the wide front door for them. She still wore her outdoor things, which were wet and heavy with snow. “I’m so glad you’ve made it back to us,” she said, taking their coats and hats. “I was worried about you.” She chanced a look at Libbie before crossing to the hall closet, nearly running into her mother-in-law, Hanna, who had just then come into the room from the kitchen.

“We are all so sorry to hear about the girl. What a thing to happen.” (Caspar and Max had been sent for earlier to help with the search for Eleanor.) “She couldn’t have been in her right mind, poor thing.”

“I can’t stop thinking about her,” Adelaide said from inside the closet.

“We all feel that way, Addie,” Libbie called.

“Is someone with her now?” Adelaide asked, joining them again in the front hall, her eyes wet with tears. “Surely someone will stay the night with her? One of your teachers?”

“I would have,” Libbie said. She nodded at Alex. “We both would have. But the men from Graynam’s have already come to take her.”

“Where is the child’s home?” Hanna asked.

“Baltimore,” Alex and Libbie said, unintentionally, in unison.

“What an awful trip,” Adelaide said. “Even to think of it, in winter. It’s so terribly lonely to imagine her making it now as a piece of cargo. I wish we could keep her here on the grounds with us, make a grave for her somewhere among the trees.”

“It won’t be like that,” Libbie said, bothered by the image Adelaide had conjured. “No one will be treating her like cargo.”

Outside, the wind screamed at them. At first it was a chorus of pitches, but eventually those shaped into a single low and breathy moan, one that wouldn’t end when it seemed it should have.

“Do you know how long the storm will last?” Alex asked. The four of them looked warily out the windows at the waves of pelting snow lit in yellow from the porch lights.

“I didn’t know it was to come at all,” Hanna said.

“That’s because it wasn’t expected,” Adelaide said. “Not like this. I think it’s for her.” She paused, then added, “For your Eleanor,” though it wasn’t necessary. They all knew who she meant. Adelaide sneezed, then. And once more.

“Oh, Addie, you should have come in from the cold sooner,” Libbie said. The maid did look pale. “The clearing could have waited for morning.”

“There’ll be plenty more to clear in the morning,” Hanna said. “There’s more even now.”

“Should you stay here tonight?” Libbie asked, looking between them. “The four of you? Where is Max?”

“Tending to the radiator in your bathroom,” Hanna said. “It was giving him trouble earlier. And that’s very good of you, ma’am, but I’m sure we’ll manage.” She traded an unreadable glance with Adelaide. “It’s not so very far and Mr. Eckhart will want his bed.”

“No one can say he hasn’t earned it,” Alex said.

Both couples lived in small cottages on the property. And Hanna was right, they weren’t so very far away. But then, it wasn’t usually so very late and so very terrible out when they headed to them.

After stabling the horses and again clearing the front path, Caspar Eckhart joined them in the entrance hall, a layer of snow on his shoulders and hat. When asked about staying the night he said, without hesitating, that he certainly did want his own bed. And then agreeable Max came in from the back hallway to announce that they had enough coal to last at least a week and that he was confident the radiators would remain steaming through the night, whether or not this damned blizzard kept at it. And then the four of them insisted again, as they bundled themselves for the trek, that their cottages were not too much trouble to get to if they huddled together and moved with haste.

It was snowing so hard that it was difficult to tell it was snowing at all.

Even so, the wind smashed against the heavy front door with such force that the group had trouble closing it behind them. It was snowing so hard that it was difficult to tell it was snowing at all. It just was the air, like mist or a swarm of yellow jackets: the flakes hovered across the landscape in a constant, buzzing mass.

Even after the swing of the foursome’s hand lanterns had been lost to the swirling dark, Libbie, still looking out the window in the direction they’d headed, said simply: “I wish they had stayed.”

The Eckharts had never before chosen to stay the night at Spite Manor, not that there was often cause to ask them to, but even still. They’d rather make the trek through the woods, in the dark, in a blizzard, than stay the night in Libbie’s home.

“Do you wish that all of them had stayed, or is there one in particular you’re thinking of?” Alex asked.

“I’m thinking only of the storm, Alex.”

“Of course.” And then, by way of half apologizing, Alex added, “They’re just glad to be alone together. In their own homes.”

“I remember when we once felt like that,” Libbie said. She was immediately unhappy with how churlish she sounded, even if she meant it.

But then Alex made it worse: “I’m not sure we ever have. Not here.”

Outside the wind moaned like a wailing phantom and Libbie shivered. Again.