Libbie Brookhants Takes a Bath

It wouldn’t stop snowing at Breakwater.

The constant howl of the wind outside was cold and hollow, the white on white on white out the windows dizzying if you looked at it for too long.

Snow fell so ceaselessly from a sky hung low that it seemed like the clouds were disintegrating. And there was no keeping up with the shoveling. Oh, you could try, Readers: but you would fail.

The snow came and came. Perhaps it wouldn’t ever stop.

During those long hours of waiting out the storm, such a chill settled over the house that I suppose I might as well, hereafter, go ahead and refer to Breakwater as Spite Manor.

Because let’s be clear: this is what the house has always wanted to be called, what it has always deserved to be called.

And Libbie had never felt more trapped inside it. She was still waiting for Alex to finish the book, to come see her with fresh complaints about it. Or with questions Libbie would not want to answer. If she let her mind drift, it lingered on Brookhants and the trouble she suspected was marinating there without her. And those thoughts filled her with a buzzing dread.

She wandered the hallways, but somehow Hanna seemed to be around every corner—polishing this or putting away that. Libbie wasn’t someone who minded having house staff so much as she minded being reminded about the many things those staff did for her. So she found herself needlessly adjusting the portraits on the walls or pulling threads from a carpet fringe, if only to appear that she too was contributing to the running of her home.

She had finished her first cup of coffee, then drank another right after, and part of another after that. Now she had a stomachache and a headache, too. She tried to have a longer conversation with Max about Adelaide’s health. He had been thawing a pipe in the cellar and she caught him in the kitchen warming himself over the stove. But he refused to elaborate on Addie’s strange symptoms and it was soon clear to Libbie that she was not only being intrusive, but also keeping him from his work, and he was too polite to say so. She apologized for holding him up and he looked most relieved to slip back down the stairs away from her.

Libbie couldn’t even spend these hours with Alex, because as soon as Hanna had delivered the doctored book to her, she’d positioned herself on a settee in the parlor and hadn’t left it, though she did keep sighing—more so if Libbie crossed through or even near to that room. So much sighing. Eventually, Libbie decided to stop being bothered from afar. She found a novel she’d been looking forward to, Maugham’s Mrs. Craddock, and chose a chair near the fire. (And near to Alex, too—the room was small.) Libbie did manage to read a few pages but found she couldn’t focus. The words slipped into each other, the lines blurred, she lost her place. And then a sigh from Alex. And another.

Libbie had already told Hanna that they’d have their supper at seven, and so with more than two hours to spare, but night already descended—wretched, wretched winter!—Libbie Brookhants went upstairs to draw herself a bath.

Expensive and modern plumbing innovations were the exact kind of thing on which Harold Brookhants could spend hours ruminating. So it’s no surprise that he’d been particular about these elements of Spite Manor’s design. The house had three full bathrooms, each with a large bathtub, two of them with separate showers as well. These were in addition to the built-in sinks in the dressing rooms. When their house was being built, Libbie had found Harold’s preoccupation with things like exposed nickel plumbing very dull indeed, though she did now appreciate how modern and convenient the bathrooms were.

But they were also cold. Even with the radiator scalding to the touch, Harold’s insistence on marble flooring and marble panels for the walls left the rooms with a chill in the winter. Especially on a day like today.

And so now Libbie Brookhants let her bathwater run hot. Great clouds of steam swirled up from the tap as she waited for the cold tub to fill. It would be a wait—the tub was large. If Adelaide had been present, she’d have readied the room for Libbie, drawn the bath, helped with her disrobing if she’d wanted, which she often did not.

Adelaide was such a curious addition to the household. Welcome (at least for Libbie), but curious. Max had met her the previous spring, when he’d been asked back to Harold’s (former) Pittsburgh estate to run a small landscaping project for Harold’s sister, Cecilia Brookhants Taunton, who now owned said estate.* Max had been rather adorably proud to be asked back, so even though Libbie wasn’t much a fan of Cecilia, and even though it was a bit of a strain on things to manage for a month without him—Libbie had been happy enough to let him go.

And then, surprise! Max returned home engaged to Miss Adelaide “Addie” Trevert, who was then employed as one of Cecilia’s housemaids. And oh was Max ever in love with her. They’d had their engagement portrait taken together before he’d left Pittsburgh, and for weeks after, Max carried the cabinet card of that photograph with him at all times, happy to find a reason—or invent one—to show it.

Also, there was this: Cecilia had offered him full-time employment, if he wanted to move back to Pittsburgh that is.

“Of course, I’d rather stay here at Breakwater, Mrs. Brookhants,” Max had said when he’d presented this dilemma to Libbie. “But I wouldn’t want you to feel that I’m forcing your hand.”

(If that isn’t forcing your hand, I don’t know what is had been Alex’s response to the matter.)

At any rate: Adelaide had joined them in August, mere weeks before the semester began.

Right from the start, Alex hadn’t liked her very much. She claimed that Adelaide was lazy, even spoiled. She said that Addie did as little as she could get away with doing (or not doing), and that Libbie didn’t see it only because the maid was always playing up to her; because Adelaide was pretty and sensitive and doted on Libbie.

For her part—at least at first—Libbie thought that Alex was just catching Addie at the wrong times, and that she hadn’t settled into her position within the household yet.

And so what if Addie did dote on her a little? So what? It was nice to be doted on.

Libbie also sensed, from a few surprising remarks that had passed between them, that Adelaide was much more intelligent than she always let on. Libbie had even wondered about asking Addie if she’d like to sit in on a class or two. Or perhaps to be tutored occasionally in subjects of particular interest to her. Of course, Alex would surely object, not only because Addie was older than the Brookhants students, even the seniors, by five or six years, but because Alex—though she was loath to admit it in mixed company—thought that Libbie should hire more house staff, not fewer. Certainly, she wouldn’t like the idea of Adelaide skipping her work to visit campus. And Hanna probably wouldn’t like it, either. Though perhaps Max could be persuaded: anything and everything for his still-new wife.

Libbie dipped her hand into the bathwater to test its temperature. She crossed the room to a cabinet to retrieve a bottle of salts, but upon opening the door and seeing them on the shelf, the memory of her nightmare—the fountain, Mary MacLane’s laughing face—shivered within and she changed her mind about using them. She did, however, unwrap a new bar of soap: lilac scented and hand milled in Marseille, another summertime gift from Sara Dahlgren and crew, who had spent much of the previous year in France and were now likely there again, living une belle vie even in winter.*

As Libbie slipped into the bath—the exquisite burn of entry taking her breath—the displaced water almost, but not quite, crested the rim. She’d filled it too high. She turned off the faucet, and as she settled, she flitted between these thoughts: Adelaide and her untapped smarts, Sara Dahlgren and her Parisian women, the reason for the chill between herself and Alex, and poor dead Eleanor Faderman, carried as frozen cargo to Baltimore only to soon be buried within its frozen ground.

Libbie stretched the length of the tub. She soaped herself until the water clouded and the scent of lilacs filled the room. That scent returned her, as it almost always did, to the night of the Follies, the night she claimed Alex as her victory. How fine and strong Alex had seemed to her then, how assured. Even now, though years and years had passed and each of them was far too known to the other to sustain that kind of flame, Libbie’s distinct memory of that previous Alex, Alex the Flirt—the one who had been built as much of rumor and notion as flesh—made the version of Libbie now in the tub warm with desire.

She rolled a hand towel and placed it at the nape of her neck, wedged it there against the tub’s wall under the weight of her resting head. She closed her eyes. She let the soapy, scented water slip in and out of her mouth. It almost tasted sweet, but that was surely a trick of the scent. When her hand eventually met the pulse between her legs, she no longer thought of young, brave Alex, but of Adelaide. Adelaide in her cleaning bonnet, reaching high to dust a ledge; Adelaide asking if she might borrow this or that book; Adelaide bringing her coffee early in the morning, when neither Alex nor even Hanna knew that she, Libbie, was in fact awake and at her desk atop Spite Tower. But Adelaide knew this and would visit her sometimes. “I brought you this,” she’d say, leaning close to Libbie in order to set the coffee down before her. “I thought you might want it.”

“I do want it,” Libbie would say. “Aren’t you wonderful to think of me?”

But it wasn’t this vision of Addie leaning close at her desk that she lingered on. Libbie had moved on to a much stronger memory, one she didn’t allow herself to peek at very often because she didn’t want to diminish its effect.

That August, shortly after their friends had left and before the students had returned, while Adelaide was still new to her employment at Spite Manor and while Libbie and Alex were still in the thrall of their reenchantment with one another, Libbie had noticed Adelaide watching them from the dressing room.

Each of the dressing rooms linked to the bathrooms proper—this had been one of Harold’s design specifications—and so at first, when, from her bed, Libbie noticed a presence there, she assumed that Adelaide had simply slipped into the room from the bathroom side in order to put away laundered garments and would slip away again just as quickly, likely even more quickly, and with great embarrassment, once she realized that the bedroom was currently being privately occupied. Very privately occupied.

If it had been Hanna, Libbie would have stopped Alex at once and they would have pretended, however awkwardly, to be only taking the afternoon nap they had said they’d each be taking.

But it wasn’t Hanna in the dressing room. Hanna’s steps were heavier and her shape, even in shadow, thicker.

And then, Readers, a curious thing happened: Libbie sensed that Adelaide wasn’t leaving in a hurry, embarrassed to have caught them. In fact, she seemed to linger in the dressing room.

At first, Libbie couldn’t be sure she was seeing what she seemed to be seeing. The light in the bedroom was dim, its heavy curtains closed against the brightness of the afternoon.

And yet a person again moved behind the gap in the dressing room door. She was still there.

And now the shadow figure—Adelaide, it was Adelaide—seemed to be right up against that door, looking through the gap and into the bedroom. Libbie felt she could practically hear her breathe!

She was watching them.

Surely she knew by now what it was she was seeing—even if chancing upon them had been, at first, an accident.

Alex—her head between Libbie’s pale legs—knew none of this. But Libbie, her own head resting upon the bed pillows, had a clear sight line to the dressing room and its door gap. Adelaide mustn’t have thought that Libbie could also see her. Adelaide must have believed herself to be hidden behind the cover of that almost-closed door.

It was quite dark in the bedroom.

But now that Libbie knew Adelaide was there watching, the thought of her continuing to do so, choosing to watch, thrilled her so completely that Alex soon commented on how quickly her pleasure had come.

Libbie could never tell Alex about Adelaide watching. Something like this would only pinch at, provoke, the discomfort already between them. And what’s more: Alex had believed that Libbie’s excitement that afternoon was due to her efforts alone. She would be embarrassed and angry too, to learn otherwise.

Truth be told, Readers: Libbie liked keeping this secret. She liked it very much.

And there was also this: right before she’d reached her peak—for in the rush of those moments she closed her eyes—she’d felt the sudden certainty that Adelaide herself knew that Libbie had discovered her presence. Which meant that they were, in fact, watching each other. Libbie couldn’t confirm this without asking her, which of course she would never do, but she knew it in a deeper place than the answer to such a question could get at, anyway.

The thought of that day, now in the tub, was enough to bring Libbie there again.

After, she drifted into hazy sleep. The bath was hot. The steam in the room was thick and scented in lilac. And she was so tired and momentarily contented. It was easy to give herself over to it.

It was the choke of salt water that woke her.

As she slept, Libbie’s towel pillow had slowly, slowly slid down the wall of the tub—and her head and neck and shoulders along with it—until her mouth reached the surface of the water and some of it slipped in past her lips. This was the exact danger of napping in a bath and Libbie Brookhants felt it as water reached a throat not prepared to swallow. She coughed and spit and shot her eyes open, yanked from sleep and panicked, splashing water out and over the edge of the tub as she jerked to sit upright.

And to breathe.

For a few moments she could only cough and take clogged breaths and assure herself that she was fine, she was safe. For a few moments she couldn’t make sense of where she was.

The bath. She was still in the bath.

Only, the room had gone dark. Hadn’t she switched on the light?

The snow through the window did cast a pale white, but the room was the color of coal smoke anyway—the sink and the cupboards only hulking shapes as she tried to settle her eyes.

And then there was the buzzing, steady and low, almost like the hum she had heard in her study that morning.

She licked her lips, her throat sore. Why did she taste salt?

She pulled a hand from the tub and sucked her fingertips. Salt water: exactly as if she’d brought it in from the waves below.

The buzzing now hopped off, hopped on, hopped off again. Louder each time it returned.

She squinted. It seemed to be coming from somewhere above her, maybe along the crown molding. It was too dark to see anything there.

The buzzing stopped. It started.

Bad wiring? It could be that she had put on the light but then it had gone out with this buzzing as its cause or symptom. Maybe something to do with the storm?

Libbie reached to pull the plug, to drain some of the water before she moved to climb out of the tub. As she did this, her fingertips skimmed something around the stopper. She jerked her hand away. Then she felt again, more tentatively, primed for revulsion.

Again her fingers found it: a thick coating of algae—slimy feathers of it—and not only around the stopper, either. As fast as she could feel for it, it seemed to spread, until it coated the bottom of the tub, until she was sitting on it, her naked skin pressed against its awfulness. And now, even as she watched, it climbed like a shadow up the sides of the tub’s enameled walls.

It could not be, but it was: algae spreading like a heap of skittering spiders, its black legs reaching and racing.

She screamed for Alex, but the buzzing was on again and now so loud—so much louder than before—and Alex a floor below and several rooms between. Libbie knew she wouldn’t be heard. She needed to stand. She needed to get herself out of this mad bathtub.

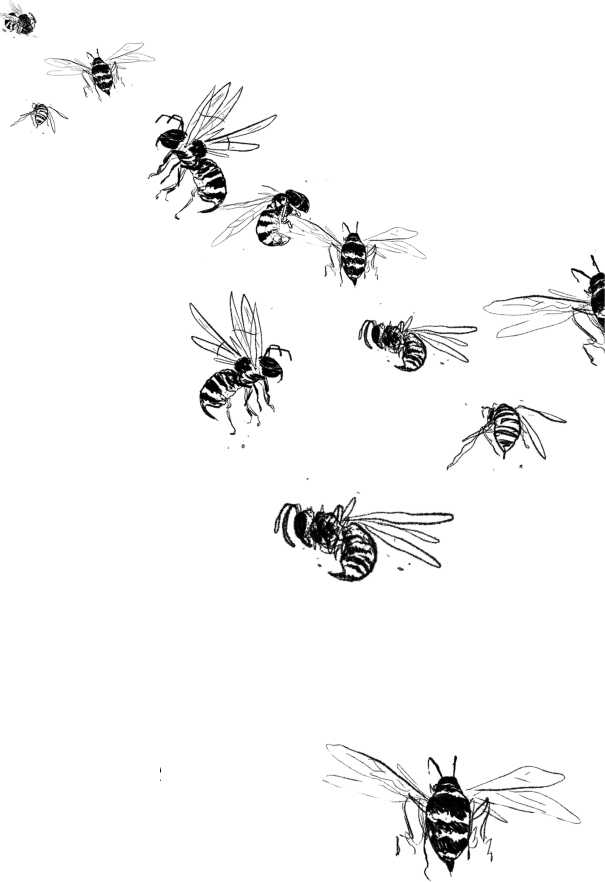

She tried to grip its rolled rim, but the algae was already there, thick and noisome but with a distinct note of former sweetness gone bad. It was the scent of lilacs left too long in a vase, the water growing rank—a miasma of rot and perfume both, like the fountain from her nightmare. She pulled her hands back and turned them over, saw black algae on her palms and fingers. She dunked them back into the tub, but as she tried to scrub them clean, the buzzing grew louder still, until she could place it exactly. Yellow jackets.

The sound was the horrible buzzing of a swarm of yellow jackets.

Libbie again attempted to grip the rim of the tub and plant her feet hard against its bottom in order to pull and push herself up. But the algae was too slippery, so thick with slime, she couldn’t gain purchase. Her thrashing movements spilled great arcs of water onto the marble floor. It smacked hard there.

And then Libbie Brookhants watched—squinting to be sure, trembling when she was—as the antennae and black, mirrored eyes of a yellow jacket emerged from the dripping end of the bathtub faucet. Its head twitched as it felt the air.

Soon after came the rest of its pointed body and cellophane wings—its yellow stripes somehow incorrectly bright, almost as if glowing there in the dark. Now it used its sticky, jointed legs to spring from the faucet and fly in a line just over the top of her left ear. She swatted her hand at the awful buzz of it, the hideous flick of it through the air, as another yellow jacket emerged from the faucet. And then another. Until there came a stream of them.

Now, Readers, Libbie Brookhants screamed and screamed, and not only for Alex, but for anyone who might hear her, who might come. The wretchedness of the rot-sweet scent was stronger too, and the buzzing, the buzzing was everywhere, joined by the sounds of the faucet-sprung yellow jackets now careening between the bathroom’s walls.

And now, oh God, she sensed some dark presence in the dressing room, a scuttle, a shift of shadows, there beyond the gap—the door not quite closed. There was only a line of space through which to see, but just as in the memory she’d used to pleasure herself, Libbie was certain that someone now stood in the dressing room, watching her.

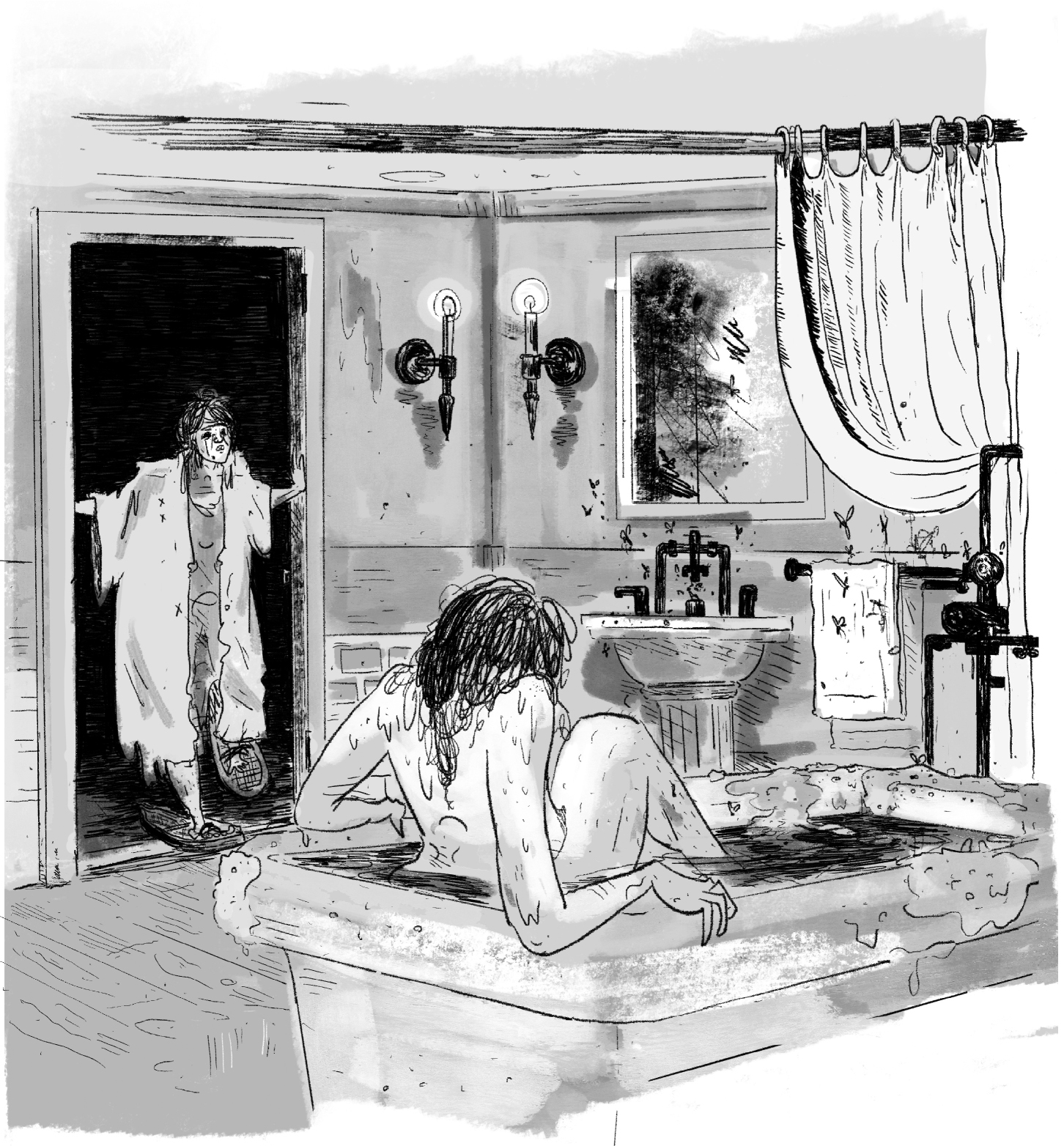

“Let me help you, Mrs. Brookhants,” Adelaide said, opening wide the door.

Maybe Libbie, at first, felt a brief ripple of relief, but if so, it ended in cold dread as Adelaide Eckhart took her first steps into the room—strange, stilted steps. This was because, Libbie strained to see, to be certain: Adelaide was wearing her massive snowshoes. They were like dinner platters strapped to her feet. It should have been a comic thing, Adelaide indoors in her snowshoes, being blithe and merry and making Libbie like her even more. But in these moments the effect was only additionally unsettling, especially as she neared the tub and Libbie saw her in full.

She looked very little like herself, at least not like any version of herself that Libbie had ever encountered, nor any version of any person Libbie had ever encountered. She wore one of Max’s dark wool work coats; it was still flaked with fresh snow and hung open garishly, revealing that her too-thin nightgown was all she had on underneath. Her hair was up, pinned at random, as if she’d done it in the dark, sections of it stuck to her scalp and matted with sweat.

“Let me help you, Mrs. Brookhants,” Adelaide said, opening wide the door.

Adelaide’s face, though, was the most wrong. Even in this half dark, Libbie could see that it was discolored and swollen, but only in patches, as if someone had inflated one eyelid, part of her bottom lip, the soft skin beneath her chin, and then had painted those flesh balloons in reds and purples.

“The girls told me to come to you, Mrs. Brookhants,” this false Adelaide now said through her strange, stretched mouth, her words also misshapen. “They said you’d tell me how wonderful I am to think of you.”

“Addie, you’re not at all well,” Libbie said slowly. “You must be half frozen!” Adelaide’s uncanny approach, her obvious illness, the awful warp of her face—as if behind a papier-mâché mask—had shocked Libbie into momentarily disregarding the terror of the bathtub, the yellow jackets. “Why aren’t you in your bed?”

“I like watching you, Mrs. Brookhants,” Adelaide said, now bending and reaching her arms toward Libbie as though to pull her to standing. “I think you like me watching you.”

Adelaide’s arms were also marked with welts. Libbie shuddered to see the black muck deep beneath her fingernails. She couldn’t let them touch her. “I’ll need a towel, Adelaide! You know where they are,” she said sharply, the latter part only to buy herself time.

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Brookhants,” Addie said. “Of course I do. I know where everything is here.” She turned to the cabinet, began her cumbersome, slapping steps there, and Libbie used these moments to thrust herself up and out of the tub. She didn’t care how much of the horrible seawater—a wave of it, Readers—splashed out over the side. She did care that some of the black algae wedged up and under her own fingernails with her effort, but she wanted only to be out of the water, over the rim of the tub, and standing, though as soon as she set one foot on the puddled marble it slipped out from beneath her and she crashed down, hard, smacking her hip against the tub’s edge before smashing her naked body against the floor.

“Oh, my dearest darling Mrs. Brookhants,” Adelaide said as she turned to see, towel in hand. “What have you done? Now you must let me help you.” She didn’t seem to notice the yellow jackets beginning to swarm her—five or six of them, surely in her field of vision—landing on her face, hopping from her hair to her shoulders to her chest and around and back.

Addie didn’t notice them, but Libbie Brookhants certainly did.

And the buzzing, the awful buzzing, it was everywhere: vibrating in the air and through the marble panels too, up and down the walls and along the floor, as if it was trying to force itself inside of her. Libbie watched the black algae spreading fast across the floor, like someone unrolling a carpet of it. Everywhere the bathwater had sloshed it now spread. And then there was Adelaide again standing over her and Libbie’s breath catching hard in her throat.

“Addie, am I dreaming?” she asked.

“Oh no, Mrs. Brookhants, no,” Adelaide said as she bent toward Libbie with a dirty towel stretched between her arms. “You’re dying.”

The towel was some filthy, rancid thing stained with every awful substance that might bleed or leak or spray, and there would be no saving Libbie from this. Adelaide bent closer still, and now the towel would wrap her up, Addie would see that it did, that it covered her, that she couldn’t escape it, that it was pulled around her tight and—

The overhead light turned on.

It was as if its electric glow simultaneously snapped off the worst of what was wrong. The buzzing ceased at once. Libbie was still on the floor, still in pain, but the spilled water around her was now only water: there was no creeping black algae. And while Adelaide remained standing above Libbie in her strange costume, the towel she held was clean and white and fresh from the cupboard. Adelaide’s face was red and puffed with welts, but she was also recognizably Addie and not some stretched skin mask formed from her features.

“Libbie?” Alex asked from the doorway, clearly trying to make sense of a scene that refused such an effort. She’d come to talk about Mary MacLane’s book—she still had it in her hand, in fact—and had heard the commotion from the hall, had opened the door and reached in to turn on the light. “What’s happened? Adelaide, why are you wearing your snowshoes in the house?”

“I slipped getting out of the tub,” Libbie said, reaching to take the towel Adelaide was still holding above her. She quickly covered herself. “I’m fine, but Addie isn’t. You need to find Max or Hanna and bring them here.”

“Let me help you,” Alex said, coming into the room, slipping a little as she did. The sloshed bathwater had spread across the length of the floor. Now inside the bathroom, closer and under the light, she took in Addie anew. “Oh! What’s happened to her face?”

“Alex!” Libbie said. “Please find Hanna. Now.”

Alex did so unhappily, giving Libbie, as she left the room, a look that suggested they would certainly discuss all of this later, and the book in her hand, too—but in private.

Libbie managed to stand, though her hip was throbbing. Adelaide had not moved. In fact, she held her empty arms stiffly before her, as if she were still holding the towel that was now wrapped around Libbie.

“Come with me, Addie,” Libbie said, taking her by the elbow.

Between the wet floor, and Libbie’s hurt hip, and Adelaide’s absurd shoes, they moved very slowly. Once they were finally through the dressing room and into the bedroom, Libbie sat Adelaide on the edge of her bed. She held her hand to Addie’s temple and found it flushed with fever as she’d expected, but when she went to pull her hand away, Adelaide clasped her own cold fingers overtop, holding them there while attempting to nuzzle her face against them. The towel, Libbie’s only cover, slipped down, and she had to sloppily maneuver it back around herself with her one free hand.

“Stop this, Adelaide,” she said, firmly pulling away from her reach. “Let me help you, now.” Libbie’s hip throbbed as she bent to remove the snowshoes. She saw, then, that their woven netting was variously studded with leaves and brambles and even a single delicate harbinger of the spring season then still months away: a blue windflower.* It could not be, but it was. As Libbie began to unfasten the snowshoes’ topmost leather straps, she asked, choosing her words carefully, “Adelaide, where have you been walking? What path did you take to arrive here?”

“Through the orchard, of course,” Addie said simply. “The girls told me it would be quickest, because of the snow.”

The orchard was not along even the most indirect route between the Eckharts’ cottages and Spite Manor. In fact, it was in the direction of campus.

Before Libbie could ask for an explanation, Adelaide said, rather cheerfully, “Did you love your dead husband, Mrs. Brookhants?”

And where was Alex with Hanna or Max? Earlier the house had seemed so full.

“Shhhhhhhhh,” Libbie said. “Be still now. You have a fever and you aren’t making sense. I’ll get these boots off and I’ll bring you a glass of water.” She now had one snowshoe removed. The other, the one with the flower twined up in it, awaited her efforts.

“I don’t think I love mine,” Addie said simply. “Not that he’s dead yet.”

“No, he certainly is not,” Libbie said.

“My sisters tell me what a catch I’ve made in Max,” she said, performing some kind of a simpering imitation of their voices. “And his mother tells me—she tells me all the time. Oh, he’s just so terribly sweet and good. He is, isn’t he, Mrs. Brookhants?”

“He does seem it,” Libbie said, still undoing straps.

“But I don’t want him to be,” Addie said. “I don’t want his sweetness. It makes me almost sick to have him touch me. Sometimes I want to scream and scream at him.”

Libbie had both of the snowshoes off now, and so she started on the laces of Adelaide’s boots. “Addie,” she said carefully, “is Max to blame for your face?”

“Oh, my dearest, most delicious Library,” Adelaide said, “you know better than that.” She giggled, an awful giggle. And then she began to sing:

What’s the racket, yel-low jacket?

Far afield you roam!

But you’ll never leave these grounds

for Brookhants is your home.

“Enough,” Libbie said. She shivered. She was still wet beneath her towel but that wasn’t the cause: it was Adelaide’s perfect knowledge of a song she should not know.

Just one sting will make us smart.

With two, we might be brave.

“Quiet now!” Libbie said.

Three will buzz inside our hearts.

With more, we’re in the grave.

“Adelaide, stop—” Libbie started, nearly in tears at how wrong this all was, but she was interrupted by commotion in the hallway and then—

“What in heaven!”

Hanna, her skirts rustling with her efforts, rushed into the room followed by Alex, who was still carrying the book, and who would have likely still been pouting over being sent away earlier, had she not just caught the final lines of Adelaide’s song.

“Dear girl, why are you here?” Hanna asked as she reached the bed. She did not wait for an answer before adding, “Why did she come?” She looked at Libbie to explain.

“I don’t know!” Libbie said, finally pulling free one of Adelaide’s boots. “She won’t tell me anything that makes any sense. She came in from the dressing room while I was taking a bath, still in her snowshoes.”

“But you’re leaving out so much, Mrs. Brookhants,” Adelaide said, grinning.

“It’s her fever,” Hanna said quickly as an apology. “She doesn’t know what she’s saying.”

“Yes, I do!” Adelaide said. And then, as if giving a formal recitation, she clasped her hands to her chest and spoke brightly: “There is the element of Badness in me. I long to cultivate my element of Badness. Badness compared to Nothingness is beautiful.”

“You see, it’s pure nonsense,” Hanna said. “It’s her fever talking.”

“It isn’t nonsense at all,” Alex said, her face gray. “It’s Mary MacLane.”

And, Readers, it was. Addie had just offered a partial recitation from the final lines of Mary’s March 19 entry.

“Oh Kind Devil,” Adelaide said, looking between them and giggling, “deliver me.”