Road Apples

Audrey did not want to be in an SUV on the way to a strip mall in Tiverton. They were now six days into filming—six messy, not particularly successful days, if you asked her—and tomorrow both she and Harper had five A.M. call times.

And yet here she was: in an SUV on the way to a strip mall in Tiverton. With Merritt along, too.

Only Merritt did not have a five A.M. call time. She would likely wander onto set the next day whenever (and if ever) she felt like it. From what Audrey could tell, and to Bo’s annoyance, thus far Merritt had spent about half of her time at Brookhants in front of her laptop. The night before, in fact, when she’d been brushing her teeth for bed, Audrey had looked out the open window of her tiny house and through the window into Merritt’s. Her cottage was dark except for the cool wash of light from her laptop screen, which was wrapped around her like a private fog. If Audrey listened for it (and silenced her electric toothbrush) she could even hear the tap-tap-tap of Merritt’s hands over her keyboard. Audrey had wished for binoculars so she might read the screen.

She should ask Bo for a pair. If she did, she felt certain they’d show up on the counter in her cottage, probably with a little note attached. Just now there was yet another little note from him on her phone screen in the form of a text:

Something coming up ahead in the road. Get out of the car to look.

It was dusk, and Carl Eckhart was driving them through the woods surrounding Brookhants on a dirt road reopened by production only days before. There was tree canopy above and they were enclosed on either side by tall trunks and looming dark, some patches deeper than others.

Audrey was in the seat Bo wanted her in, left side behind the driver. Harper was up front with Carl, because of course she was—the two of them having apparently already attained their mutual ride-or-die status—and Merritt was next to Audrey. Audrey happened to know that this particular Range Rover was rigged with cameras and microphones aplenty. (And she was wearing her own concealed mic.) Bo had been sending her rushed texts about blocking, about how best to incorporate this or that when she played this scene. Because that’s what it was, for Audrey: a scene. One that had come up earlier, apparently, than Bo had been planning for, but he was capitalizing on the opportunity.

For Harper and Merritt, it was a spontaneous trip, happening only because Harper had said she was craving a Cherry Coke slushee and some greasy pizza and Carl had overheard and said he knew where there was a convenience store in Tiverton with an Icee machine.* And it happened to be in the same strip mall with a, as Carl put it, “pizza joint.”

“So Caspar and Hanna were what, your great-great-grandparents? Great-great-great?” Harper was now asking Carl. “I can’t ever do family math right.”

“Not grandparents,” Merritt said, her face in her phone, but not missing a word. “Can’t be. Max and Adelaide didn’t ever have children. Remember, Hanna—”

“My relation to them is a lot more distant than that,” Carl said.

Audrey smiled at Carl not caring whether he cut Merritt off.

“Well, you got the last name anyway,” Harper said. “That’s what matters.”

A fresh text from Bo landed on Audrey’s phone: Get in there! Ask him about what he knows about the curse. Something!

Her heart rate ticked up. She played out a few options in her head, thought them each stupid, and decided to go with what she hoped was the least stupid. She took a breath, leaned forward a notch, and asked, “Carl, does your family believe in any of the curse stuff? I mean, did you, like, grow up thinking of it as real?”

She thought she sensed an eye roll from Merritt, but to be fair, it was only a sensation. And this Merritt, the one who had shown up with Elaine in that green convertible, was notably changed from the Merritt Audrey had met back at Bo’s bungalow of horrors. She wasn’t kind, exactly. But she wasn’t outwardly cruel and needling, either. (At least not yet.)

Carl scratched at the back of his hairline, pushing up his Red Sox baseball cap as he did so that it now sat crooked atop his head. “I don’t know,” he said. “Me and my sister would sometimes scare each other about things we pretended to see in the woods that we didn’t. Least I didn’t.”

“Like what?” Harper asked. She appeared to revel in this line of inquiry.

“Oh, like witches around their cauldrons, I guess. Or ghosts. One time I told Sue, that’s my little sister, that I’d found a skeleton buried by the hot springs. She didn’t quite believe me, but she still came with me to see it. I waited until she was bent over looking for it and then pushed her in.”

“Sounds like you were a jerk,” Harper said. “Does Sue even still speak to you?”

“She does, in fact,” Carl said. “She’s a better human than I am.”

“Not hard,” Harper said.

And it seemed like that was it, they were moving on from the topic of cursed Brookhants as it pertained to Carl Eckhart. Audrey waited for somebody to ask something else, except everyone but Carl had their eyes on their phones; it was again quiet enough to make out the seventies soft rock playing on the satellite radio station.

She had to be the one to do it. Again.

“But did you ever talk about, like, the girls who died?” Audrey asked, again leaning forward in her seat so that Carl would be certain she was speaking to him. “Or anything about the curse—I mean, in specific?”

She felt so obvious, desperate. She wasn’t any good at this.

“I can’t honestly sit here and tell you that it came up a whole lot,” he said. “But you’re right—somebody must have told me some of the history at some point, because I know it now.”

“Maybe other kids?” Merritt said. “I interviewed some locals for the book and most of them had at least one Brookhants story that they thought was better than their friends’ one Brookhants story.”

“That could be,” Carl said, looking for her in the rearview, but Merritt’s face was still tilted down to her phone, so he found Audrey’s instead. “Probably my friends knew some of it better than I did. I was never into that stuff.” He winked at her. “Not the answer you were looking for, huh?”

Audrey responded quickly, “No, it’s—I didn’t have one I was looking for. I just wondered what you thought of all this. I mean since it’s the reason we’re making this movie and you’re connected to it personally.”

“I think they’re paying me too much money to drive you three around, so I’m fine with it.”

“Not the hero we want but maybe the one we need,” Harper said.

Another text from Bo: Keep it on this track.

Audrey did not have anything else to ask on this track. Nothing. She was tired. This was dumb and she was bad at it. Plus, she had a real scene, a Clara Broward scene that would ask a lot of her, the following morning. That’s what she should be thinking about now. Not this.

They’d been rounding a bend in the narrow road, the trees so clogged and heavy around them that they formed a kind of tunnel. And as soon as the road straightened again, there was something in the middle of it.

“Shit!” Carl’s sudden braking lurched them forward with enough force to be snagged by their seat belts and jerked back. Audrey’s phone flew out of her hands and into the front of the SUV, where it smacked hard against the windshield. Merritt shrieked and the four of them, to a person, rubbed their necks at the whiplash.

“Everybody alright?” Carl asked. They were now fully stopped in the road.

“Not so much!” This from Merritt. “What was that?” She made a can you believe this guy? face at Audrey.

“There’s something in the road,” Harper said. She had already undone her seat belt and now popped open her door to climb out.

“What’s in the road?” Merritt asked, leaning forward to better see out the windshield.

“Bunch of boxes of something,” Harper said.

“I’ll go look,” Carl said. He opened his own door. “You stay—all I need is to be the one who gets you run over.”

“Oh c’mon,” Harper said. “Who’s gonna run us over? This road didn’t even exist until, like, yesterday.” She hopped down to join him even though he kept arguing with her about it.

Audrey stretched between the front seats in order to reach her phone where it had dropped onto the floor. As soon as she touched it, she could tell that its screen was shattered.

“Was that your phone that flew past my face?” Merritt asked.

“Yeah,” Audrey said as she sat back and looked at it: it wasn’t working, like shards of glass popped from its spiderweb black screen not working. “Unfortunately, I think Carl just killed it.” She tilted it at Merritt so she could see the shattered screen.

“Fuck,” Merritt said. She’d been charging her own phone and now she handed the cord to Audrey. “Maybe try this?”

A piece of glass fell from the phone’s screen even as Audrey plugged it in. Nothing happened.

“I’m sorry,” Merritt said, watching the screen stay dead. “Tell Carl he has to buy you a new one.”

Outside, Harper and Carl laughed together at something.

“So are you participating in this inanity?” Merritt asked.

This was Audrey’s moment, but how to play it without Bo on her phone? “I guess so” is what she went with. She opened her door but didn’t move.

“OK. Let’s forgo all reason and get out of the car here in the darkest part of the woods to look at the thing in the road that’s not supposed to be there.” I bet you know, Readers, exactly how Merritt said this. But she did undo her seat belt and open her door.

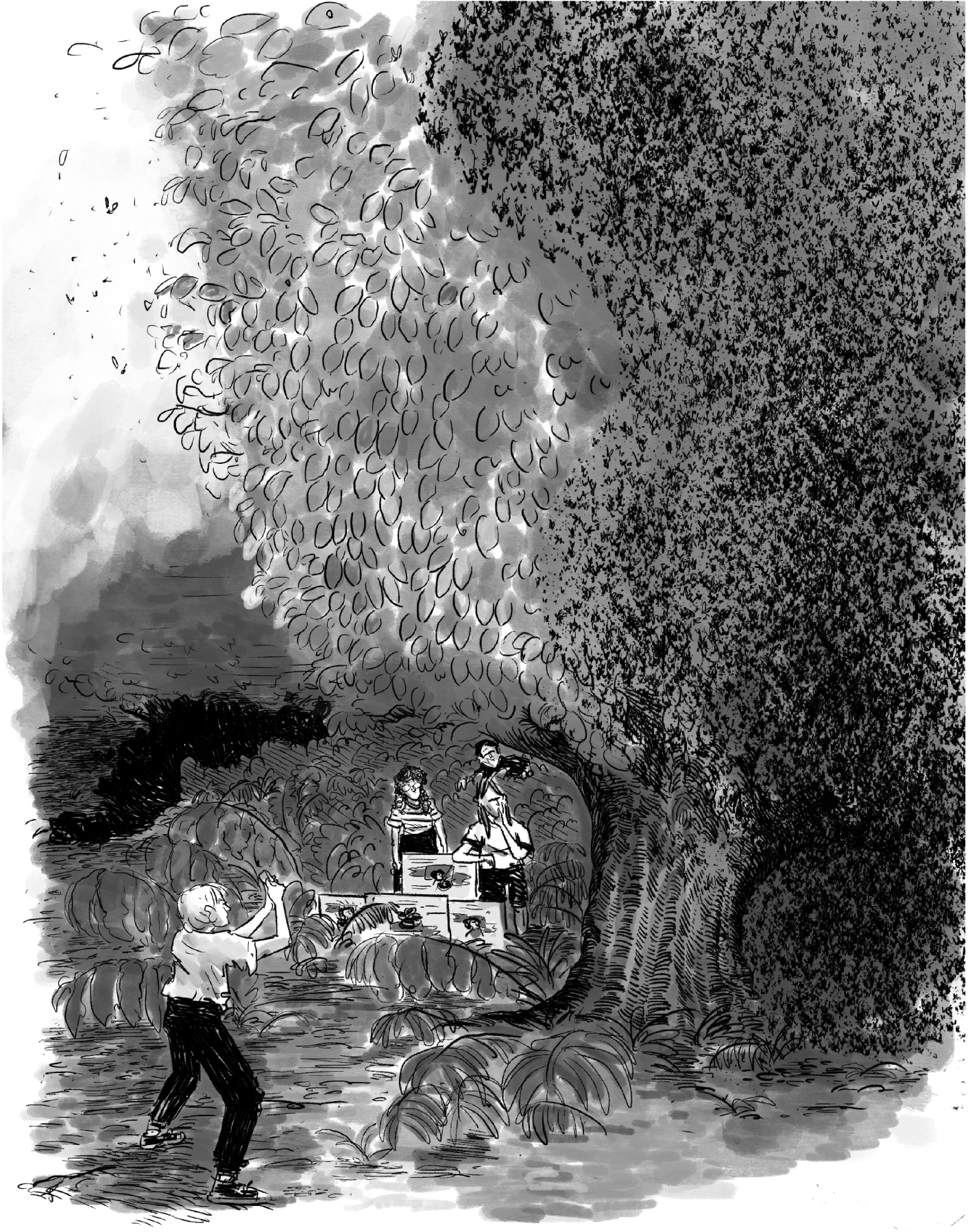

Outside they were submerged in the green light from the leaves overhead. The dense mugginess added to the feeling of being underwater in a pond. Or a scummy fountain.

Audrey joined Merritt in front of the SUV and they walked together. Carl and Harper were blocking their view of the things in the road. And then Harper bent over them. She was already using her phone to take a video of whatever it was.

Carl turned as he heard them approach. “Apples,” he said, as if he didn’t know the meaning of the word he’d just used. “I got nothing.”

Merritt and Audrey peeled apart, moved around Carl and Harper to see what he meant.

Apples is what he meant: three antique wooden crates of Black Oxford apples, two placed side by side and one centered on top of them to form a small pyramid there in the middle of the road. A few yellow jackets made lazy swoops above and around these crates, and now around the four of them as well, though not enough to pay much attention to. It was a reasonable, even expected, number of yellow jackets for autumn and crates of apples.

“I have no idea what these are doing here,” Carl said.

“Well, obviously somebody put them here,” Merritt said. “They didn’t bounce out the back of a truck into this nice stack of three.”

“Or what if they did?” Harper said. With her nonvideoing hand, she took an apple from the crate atop the pyramid and held it up to her phone’s camera lens. Then she situated her face into the frame and took a bite.

“Harper!” Merritt said, though even she seemed surprised by the force of her reaction. She regained her detached voice to add, “That seems ill advised given that you don’t know how these road apples came to be.”

“Road apples are what you call horse droppings,” Carl said.

“I did not use the term by accident, Carl,” Merritt said.

“It also seems ill advised given every fairy tale ever,” Audrey said. This comment earned her a nod from Merritt, which pleased her a stupid amount.

“It’s a good apple,” Harper said, chewing as loudly as possible for her video. She then took another large bite, because of course she did. “Like, really good.”

“I mean, they have to be from Brookhants, right, Carl?” Audrey asked. She had to stop saying right, Carl after every question, but this was what came from making her be the screenwriter, too. She wondered how they were even filming this. External cameras on the SUV, or drones? Or did Bo have a crew camouflaged somewhere nearby in the woods?

“Could be, I guess,” Carl said. “This is what’s in the orchard, but nobody I know uses these kinda crates anymore. And we haven’t picked ours yet, either. It’s still too early.”

“Spooky,” Harper said, midbite. She seemed to be done with her video, her phone no longer held aloft.

“Is it?” Merritt said. “Seems like someone’s idea of a prank. One that’s too enigmatic to mean much of anything.”

“I think she looks like Mary MacLane,” Audrey said. She kneeled to examine the smiling lady holding the apple on the crate’s paper label, Black Oxford printed in script over the image’s bottom. Audrey did actually think this, but she also knew it was the kind of thing Bo would want her to say.

“Oh shit,” Harper said, kneeling, too. “Yeah, she does.” She looked up at Merritt for confirmation.

“I mean, she doesn’t not look like her,” Merritt said. “Her style is from the right era, anyway.”

“So do we bring them with us or just move them to the side of the road?” Carl asked.

“Bring them,” Harper said.

“Side of the road,” Merritt and Audrey said exactly together.

“You’re outnumbered,” Carl said to Harper.

“Not if you make it a tie.”

“I can’t,” he said. “I’m also for side of the road.”

“Nerd,” Harper said, but she slipped her phone into her back pocket, tossed her apple core into the woods, and bent to lift the top crate. Carl went for the one nearest to him, but Merritt got to it sooner, and before he could reach the crate in front of Audrey, she had bent over and lifted it, too.

“Well this isn’t right,” Carl said, his arms still empty.

So it was that our three heroines walked the apple crates to the side of the road and moved them just off its edge, into a spread of massive ferns, their fronds growing up from the ground like too many webbed fingers reaching.

As the heroines stood, a breeze stinking of rank ocean came through the trees and made them look into the woods beyond.

Merritt saw it first.

“What is that?” is all she asked. Now the others looked where her face was pointed and saw it, too.

Though what it was they were seeing was unclear.

It was a vertical shape, like a shadow made of static, maybe forty yards off into the trees and trees and darkness. It drifted behind trunks and back out again, hovering and pulsing.

Now that they were silent and watching they each, to a person, could hear a kind of low hum emanating from it.

“Jesus fuck,” Carl said between his teeth. “It’s a swarm of wasps.”

“Yellow jackets,” Harper said like a reflex.

“Let’s back it up slowly now.” Carl was already doing the thing he instructed—one step and then two.

“Why are they going up and down like that?” Harper asked. She took the same number of steps Carl had taken, but instead she took them forward, into the woods, toward the drifting swarm.

“Harper, you don’t mess with these,” Carl said, his voice sharp. “I’ve seen them take down a deer.” He’d now moved another few steps back and down the road in the direction of the SUV. “We can get a good look from behind the windows when we drive by.”

“Yellow jackets,” Harper said like a reflex.

“It isn’t coming toward us, I don’t think,” Merritt said. “It seems like it’s hovering.”

“For now it is,” Carl said. “They can move whenever they want. Fast.”

“Why are they in that shape?” Harper asked again. She was still walking, slow step by slow step toward the mass, and now a couple of yards off the road and into the woods.

“It doesn’t matter,” Audrey said, letting panic infect her voice. “He’s saying it’s not safe. Please don’t go any closer.” Was that too much concern? Was she overdoing it?

Even if it was too much, Harper seemed to listen. She stopped moving in the swarm’s direction but pulled out her phone again to start filming.

Though the shape did not appear to drift any closer, its hum was somehow denser and stronger, the notes low and pulsing like plucked strings through the trees. Audrey could now feel that hum in her body, settling in her blood and bones where she did not want it to be.

Carl wasn’t even with them anymore. He was back at their vehicle, climbing in.

The shape drifted in and out of shadow. Sometimes its outline was clear and sharp, then it would muddle and fuzz, its contours smudged. It seemed to make the very air around it vibrate.

“I’ve never seen anything like this here,” Merritt said. They were standing close now, Audrey and Merritt, shoulders brushing—with Harper those couple of yards in front of them, in the woods. Carl was, for the moment, forgotten.

“I thought there were always yellow jackets here,” Audrey said in a near whisper.

“There are,” Merritt said. “But I’ve never seen anything like this here. Not firsthand.”

The hum churned on like an incantation while the smell of sick seawater clogged their noses.

And then—

The SUV’s ignition startled them. By the time they turned to look, Carl had it nearly behind them. As the passenger-side window rolled down he said, “Your ride, ladies.”

Merritt did not wait for further instruction to climb in, and Audrey, without her phone, didn’t know if she was supposed to or not. So she did. Just in case it wasn’t a Bo trick. (But it had to be. Of course it was.)

“We go now, Harper,” Carl said, his voice raised and firm. “Please—I’m asking you.”

Harper lowered her phone after he added the please and turned and walked to the car, too—though she took another couple of apples from one of the crates as she passed.

“God, I hope my video turned out,” she said when she got in. “That was bananas.” Harper set the apples she’d grabbed in the front cupholders and turned around in her seat to face Merritt and Audrey. “My heart’s going a mile a minute. Did you see its arm?”

“What do you mean arm?” Merritt asked.

“That thing, like, raised its arm at us—like it was saying Come here.” Harper’s face was flushed and her eyes seemed even bluer than usual, glittery with excitement.

“How does a swarm of yellow jackets raise its arm?” Merritt asked.

“How did you not see it do it?” Harper asked. “Audrey, tell me you’ve got me here.”

“I couldn’t really see it that well,” Audrey said. “I mean, I didn’t see any arms but—”

“Oh come on,” Harper said. “Come. On. Fine. I can show you.” She climbed over the armrest and into the back and found a perch between Merritt and Audrey.

“Not safe,” Carl said.

“Look, look, I’m buckling in,” she said as she did. “Sorry, Carl.” Harper grinned as she held out her phone and hit Play.

They must have watched the video a dozen times. They watched it until they had just about arrived at the strip mall that was the reason for the trip. They watched it until Harper and Merritt agreed to disagree about what they were witnessing—the beckoning arm Merritt refused to see, no matter how many times Harper pointed it out or even traced it for her on the screen. Audrey thought she could kind of see it—or at least see what Harper meant—if she let herself see it, that is.

They watched until Harper finally had enough cell service to post it. Well, to post the apple crates that had come before the swarm first, and then to post the more frightening thing.

Her caption: After we moved the crates, this happened. Turn your volume waaaaaaay up and tell me those yellow jackets don’t look like a floating woman in a dress telling you to “Come here, child. Come here.”

Tell me you don’t see her arm reaching toward you through the screen.

“Pure poetry,” Merritt said, reading Harper’s post from her own phone’s Instagram feed.

“So you’re gonna treat this like you did the orange trees?” Harper said.

“Oh my God,” Merritt said, throwing up her hands in overdone exasperation. “Please get over the fucking orange trees.”

“I can’t,” Harper said. “I was there. I know what I saw. And so I know what you saw, too.”

“I saw sickly trees get better with appropriate care,” Merritt said. “I’m sorry, but there’s no magic in that. It’s basic botany—take a plant off the back of a windowless truck and give it some good light and water and it grows. Jinkies, Daphne! Must be the work of a ghost!”

“Audrey, please chime in here anytime,” Harper said.

Audrey did not want to chime in. Audrey had already done so, several times during the days previous, since the very day, in fact, when the orange trees that had been brought into The Orangerie as brown sticks had been found bursting with leaves and flowers and, on two of them, the green pearls of newborn fruit. She hadn’t paid all that much attention to the trees when they’d come off the trucks—she hadn’t been the one hauling them in like Harper had—but she had seen Bo’s anger about them being dead, and so agreed that their unexpected health and vibrancy was, well, unexpected. She’d agreed to that despite Merritt’s eye-rolling and shoulder-shrugging. Audrey was pretty sure this miraculous botanical recovery was another Bo Dhillon touch. She couldn’t be certain, of course, but it did have the feel.

“Those trees were dead, now they’re not. How many things like this have to happen before we melt your frozen, unbelieving heart?” Harper asked Merritt.

“Things like what?” Merritt said.

“Unexplained occurrences,” Harper said.

“How about one thing that really does defy explanation?” Merritt said. “Let’s set the bar at one real thing.”

Carl was now parking them halfway between the pizza place and the convenience store with the Icee machine. Before they got out, and without much hope, Audrey checked her phone again. It still wouldn’t turn on.

So much for further instructions on this night, Readers.